Abstract

Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are a distinct group of small noncoding RNAs (sncRNAs) that silence transposable genetic elements to protect genome integrity. Because of their limited expression in gonads and sequence diversity, piRNAs remain the most mysterious class of small RNAs. Studies have shown piRNAs are present in somatic cells and dysregulated in gastric, breast and liver cancers. By deep sequencing 24 frozen benign kidney and clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) specimens and using the publically available piRNA database, we found 26,991 piRNAs present in human kidney tissue. Among 920 piRNAs that had at least two copies in one specimen, 19 were differentially expressed in benign kidney and ccRCC tissues, and 46 were associated with metastasis. Among the metastasis-related piRNAs, we found three piRNAs (piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607) to be derived from the same piRNA cluster at chromosome 17. We confirmed the three selected piRNAs not to be miRNAs or miRNA-like sncRNAs. We further validated the aberrant expression of the three piRNAs in a 68-case formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) ccRCC tissue cohort and showed the up-regulation of the three piRNAs to be highly associated with ccRCC metastasis, late clinical stage and poor cancer-specific survival.

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the major human malignancies. About 30% of patients with newly diagnosed disease have evidence of metastases at presentation. In the setting of metastasis, the overall median survival of patients is <1 year (1,2). Understanding the molecular mechanism of RCC metastasis and finding the biomarkers for early prediction may help to guide more appropriate treatment, stratify high-risk patients for suitable clinical trials, develop target-specific molecular therapies and, ultimately, decrease RCC mortality.

Small noncoding RNAs (sncRNAs) that involve RNA interference (RNAi) are conventionally categorized into microRNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA) and Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) subgroups on the basis of their associations with Argonaute family proteins and directly or indirectly affect every biological process in eukaryotic cells (3,4). piRNAs are a distinct group of abundant Piwi-interacting sncRNAs of 24–34 nucleotides (nt) in length (5,6). They form the piRNA-induced silencing complexes (piRISCs) with Piwi family proteins in the germline across animal species (6). As one of the major “fine tuners” that regulate the activities of transposable genetic elements (TEs) or transposons, piRNAs protect genome integrity by recognizing and silencing complementary RNA targets of TEs (6). piRNAs may also mediate transcriptional gene silencing by heterochromatin formation and transcriptional repression, in which piRISCs translocate to the nucleus to interact with nascent transcripts or DNAs at the target locus (7). Owing to their limited expression in gonads as well as sequence diversity, piRNAs are the most mysterious subclass of sncRNAs. Although piRNAs have recently been shown to be present in somatic tissues and some human cancer cells, their functional significance is still not clear (8–11). Recent studies have shown differential expression of piRNAs in gastric, liver and breast cancers (12,13). However, studies of piRNA expression in clear cell RCC (ccRCC) and its metastasis have not yet been reported.

Up to 70–80% of RCCs are of clear cell type. In the study, we performed small RNA deep sequencing (small RNA-seq) of a 24-specimen ccRCC tissue cohort. We found a group of piRNAs present in human kidney tissue and ccRCCs, and many of them were conserved across species. By using the frozen tissue cohort, we profiled the piRNA expression in benign kidney, as well as localized and metastatic ccRCCs, and found piRNA expression to be associated with tumorigenesis and metastasis. Among the aberrantly expressed piRNAs in metastatic ccRCCs, we confirmed that the upregulation of three piRNAs (piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607), which are derived from the same piRNA cluster, is highly associated with late tumor stage, metastatic status and cancer-specific survival in a 68–formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) ccRCC cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RCC Tissue Cohorts

Two ccRCC tissue cohorts were established for the studies. Cohort 1 included 24 specimens of frozen tissue for small RNA-seq study. There were 6 benign kidney samples and 18 ccRCC specimens in the cohort, including samples of localized (T1-2; n = 6), locally extensive (T3; n = 6) and metastatic (M1; n = 6) ccRCC. Cohort 2 included 68 cases of FFPE ccRCC samples used for validation of the selected piRNAs associated with ccRCC metastasis. There were ccRCC specimens of stage I (pT1; n = 19), stage II (pT2; n = 5), stage III (pT3; n = 13) and stage IV (M1; n = 31). The patients (n = 18) for which frozen ccRCC samples were included in cohort 1 (the frozen cohort) all had their corresponding FFPE ccRCC counterparts included in cohort 2. The clinical characteristics of all the frozen and FFPE tumor samples/patients are listed in Table 1. All the samples were collected from ccRCC patients at the City of Hope (COH) National Medical Center (COHMC) from 1986 to 2008. The primary tumors and benign kidney tissue were sampled from nephrectomy specimens. The metastatic samples were taken from resection specimens of distant metastases. All frozen samples were snap frozen shortly after removal at operation and had been stored at −80°C in the COH Tumor Bank. The protocol for using these samples was approved by the COH Cancer Protocol Review and Monitoring Committee (CPRMC) and Institutional Review Board (IRB). A waiver of informed consent and HIPAA authorization had also been approved by the COH IRB.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients/ccRCC specimens in cohort 1 and cohort 2.

| Case numbers (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Cohort 1 (frozen) | Cohort 2 (FFPE) | |

| Patients/specimens | 18 | 68 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 62.2 ± 12.9 | 59.4 ± 12.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10 (55.6) | 39 (57.4) |

| Female | 8 (44.4) | 29 (42.6) |

| Gradea | ||

| 1 | 0 | 1 (1.9) |

| 2 | 6 (50.0) | 20 (37.7) |

| 3 | 5 (41.7) | 18 (34.0) |

| 4 | 1 (8.3) | 14 (26.4) |

| Stage | ||

| I | 6 (33.3) | 19 (27.9) |

| II | 0 (0) | 5 (7.4) |

| III | 6 (33.3) | 13 (19.1) |

| IV (primary) | 0 (0) | 16 (23.5) |

| IV (metastatic) | 6 (33.3) | 15 (22.1) |

| Sizea (cm) (mean ± SD) | 5.9 ± 2.5 | 7.7 ± 4.3 |

The tumor grade and size are only applied to the primary ccRCCs.

Tissue Sampling and Total RNA Extraction

Benign kidney and ccRCC tissue were sampled as described previously (14). Briefly, total RNA was extracted for small RNA-seq from up to three to five sections (10 μm in thickness) of each frozen tissue specimen and from approximately 107 cells of each cell line sample by using the miRNeasy Mini-Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Total RNA from FFPE specimens was extracted for PCR validation studies from up to three cores (1 mm in diameter, 2–5 mm in depth) of each sample by using the RecoverAll™ Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Ambion, Life Technologies [Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA]). DNase was added to each filter cartridge to digest genomic DNA in the total RNAs isolated, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In addition, 4 FFPE (2 benign kidney and 2 ccRCC) specimens with paired frozen counterparts in the 24-case frozen tissue cohort were studied by small RNA-seq as well.

Cell Cultures

Cell lines of embryonic kidney epithelial cells HEK-293T, RCC cells 769P, ACHN, Caki-1 and Caki-2 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). The benign kidney epithelial cell lines HKC and HK-2 were kind gifts from Shan Chen’s lab at Third Military Medical University (Chongqing, China) and maintained in our lab. ACHN, HKC and HK-2 cells were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM) (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA, USA). 769P and HEK293T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech Inc.). Caki-1 and Caki-2 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (Life Technologies [Thermo Fisher Scientific]). HKC and HK-2 cells were supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA, USA), and others were supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were cultured in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2.

piRNA Expression Analysis by Small RNA Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

The expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607, as well as hsa-miR-24 and small RNA RUN6B, was measured by small RNA quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) by using the TaqMan® Small RNA Assay and the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-time PCR System with the customized/standard TaqMan® probes and primers (Ambion and Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies [Thermo Fisher Scientific]). Briefly, 10 and 50 ng of total RNAs from cell lines and FFPE tissue, respectively, were used to synthesize first-strand cDNA, followed by real-time PCR. The PCRs for each sample were carried out in triplicate. miRNA/piRNA expression was measured by using the relative quantification method (2−ΔΔCT method). For cell line samples, the expression was normalized by RNU6B. For FFPE specimens, the expression was normalized by that of hsa-miR-24, one of the most stably expressed miRNAs, especially in human kidney tissue, as we reported previously (15).

Experiments to Knock Down miRNA-Related Genes

ACHN cells were planted in a T75 flask with no-antibiotics media 1 d before transfection. The cells were then seeded in six-well plates and simultaneously reverse-transfected with 50 nmol/L Ambion siRNA molecules (Life Technologies [Thermo Fisher Scientific]) of Ago1, Ago2, Ago3, Ago4, Drosha and Dicer genes by Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX, following the manufacturer’s protocol. After 2 d of incubation, the cells were harvested for total RNA extraction by using the Qiagen QIAzol® miRNeasy Mini Kit. The expression levels of piRNAs and miRNAs were measured as mentioned above.

Small RNA-seq and Data Analysis Including piRNA Expression Profiling

Described previously were (a) the small RNA library construction, (b) cluster generation and deep sequencing and (c) the data analysis for sncRNAs (other than piRNAs) (14). Known piRNA sequences were downloaded from a publically available piRNA database (RNAdb: http://research.imb.uq.edu.au/rnadb) (16). The hg18 genome loci that matched perfectly to the piRNA sequences were identified, and piRNA expression levels were counted by using the same method as counting other sncRNAs. The raw data were then normalized and analyzed by using the Bioconductor package “edgeR.” Differentially expressed piRNAs in benign and tumor tissues as well as in metastatic and localized ccRCCs were identified if the log2 fold change was ≥1 and false discovery rate (FDR) was ≤ 0.1. The expression profiles of piRNA were also subjected to hierarchical clustering analysis with Cluster v3.0 and Java TreeView v2.0.

All supplementary materials are available online at www.molmed.org.

RESULTS

Small RNA-seq of Frozen ccRCC Tissue Cohort Reveals piRNAs Present in Benign and Neoplastic Kidney Tissue

Cohort 1 included frozen tissue of benign kidney (n = 6), localized ccRCC (stage I/II, n = 6), locally extensive ccRCC (stage III) and metastatic ccRCC (n = 6). Total RNAs from each sample were extracted, and all small RNAs of 17–52 nt from the tissue specimens were deep- sequenced. For each sample, approximately 7.5–14.7 million sequence tags (reads) aligned to the human genome sequence dataset (hg18) were obtained, which included miRNA (40.09–72.73%), snoRNA (6.62–19.95%), scRNA (0.14–1.20%), snRNA (0.03–0.55%), tRNA (2.04–14.15%), rRNA (1.06–6.65%), miscellaneous RNA (misc-RNA) (0.02–0.05%), mitochondrial tRNA (Mt-tRNA) (0.10–3.86%), Reference Sequence (RefSeq) genes (5.72–14.62%) and unknown nucleotide sequences (3.95–15.08%) (Supplementary Table S1).

In addition to the small RNAs aligned to known sncRNA genes, the remaining reads were aligned to piRNA sequences downloaded from the RNAdb database (16). The piRNA database in RNAdb currently contains 166,373 distinct types of piRNAs originally discovered from human, mouse and other species, including 26,991 which can be aligned to the hg18 genome without mismatches. With the cutoff of 2 copies (reads) in at least one specimen, 920 piRNAs were found to be present in at least 1 of the 24 tissue specimens and used for the subsequent profiling studies (Supplementary Table S2). These piRNAs accounted for approximately 3.58–9.49% of the total small RNAs sequenced in each sample, with reads of 419,864–1,134,072 (Supplementary Table S3). These findings demonstrate piRNAs to be present in benign kidney and RCC tissue and indicate the sequences of piR-NAs to be conserved across species.

piRNAs Are Differentially Expressed in Benign Kidney Tissue and Localized and Metastatic ccRCCs

The piRNAs that were detected in benign and neoplastic kidney tissue were subjected to differential expression analysis. By comparing the tumor (n = 18) and benign (n = 6) samples, 19 piRNAs were dysregulated in tumors, including 2 upregulated and 17 downregulated (log2 ratio ≥1, FDR ≤0.1) (Table 2). By comparing localized (n = 6) and metastatic (n = 6) ccRCCs, 46 piRNAs were aberrantly expressed (44 upregulated and 2 downregulated) in metastatic ccRCCs (log2 ratio ≥1, FDR ≤0.1) (Table 3).

Table 2.

piRNAs differential expression by deep sequencing: ccRCC versus benign kidney tissue.

| piRNA ID | fRNAdb ID | Log2 ratio | P | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| piR-36318 | FR006319|DQ598252 | 3.65 | 7.63E-06 | 0.0010 |

| piR-32105 | FR162144|DQ570994 | 2.67 | 0.0008 | 0.0430 |

| piR-4018 | FR007806|DQ542907 | −1.38 | 0.0016 | 0.0798 |

| piR-58594 | FR365501|DQ597483 | −1.69 | 0.0003 | 0.0177 |

| piR-58595 | FR090905|DQ597484 | −1.69 | 0.0003 | 0.0167 |

| piR-54403 | FR158262|DQ593292 | −1.95 | 0.0007 | 0.0408 |

| piR-57849 | FR193908|DQ596738 | −2.02 | 0.0009 | 0.0446 |

| piR-32635 | FR266905|DQ571524 | −2.12 | 0.0002 | 0.0112 |

| piR-45808 | FR038165|DQ584697 | −2.31 | 1.04E-05 | 0.0011 |

| piR-45809 | FR338747|DQ584698 | −2.32 | 9.16E-06 | 0.0011 |

| piR-32986 | FR206006|DQ571875 | −2.39 | 4.15E-05 | 0.0035 |

| piR-32636 | FR227782|DQ571525 | −2.39 | 9.18E-07 | 0.0002 |

| piR-32985 | FR015567|DQ571874 | −2.42 | 4.08E-05 | 0.0035 |

| piR-32637 | FR319486|DQ571526 | −2.46 | 4.31E-08 | 1.98E-05 |

| piR-54542 | FR022849|DQ593431 | −2.51 | 4.15E-06 | 0.0006 |

| piR-54436 | FR090926|DQ593325 | −2.55 | 3.22E-06 | 0.0006 |

| piR-64616 | FR003107|DQ603505 | −2.67 | 2.61E-07 | 8.01E-05 |

| piR-43147 | FR180098|DQ582036 | −2.67 | 9.89E-05 | 0.0076 |

| piR-34434 | FR015103|DQ573323 | −3.26 | 8.80E-11 | 8.10E-08 |

Table 3.

piRNAs differential expression by small RNA deep sequencing: metastatic versus localized ccRCC.a

| piRNA ID | fRNAdb ID | L (Ave) | M (Ave) | Log2 ratio | P | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| piR-42144 | FR271551|DQ581033 | 0.06 | 31.17 | 8.67 | 2.42E-05 | 0.0037 |

| piR-44785 | FR012473|DQ583674 | 0.03 | 2.07 | 6.02 | 0.0040 | 0.0908 |

| piR-59056 | R222326|DQ597945 | 0.38 | 18.56 | 5.74 | 0.0002 | 0.0112 |

| piR-59101 | FR230731|DQ597990 | 0.56 | 16.44 | 5.56 | 7.48E-05 | 0.0063 |

| piR-60029 | FR140858|DQ598918 | 0.03 | 1.59 | 5.37 | 0.0046 | 0.0941 |

| piR-50403 | FR374932|DQ589292 | 0.27 | 4.07 | 4.65 | 0.0030 | 0.0734 |

| piR-32079 | FR240375|DQ570968 | 10.71 | 146.73 | 4.47 | 6.32E-07 | 0.0006 |

| piR-41965 | FR259053|DQ580854 | 5.42 | 75.34 | 4.43 | 8.16E-06 | 0.0026 |

| piR-57010 | FR381169|DQ595899 | 0.45 | 7.25 | 3.91 | 0.0007 | 0.0303 |

| piR-75530 | FR051200|DQ614419 | 21.20 | 185.30 | 3.65 | 7.94E-06 | 0.0026 |

| piR-34463 | FR008504|DQ573352 | 6.40 | 56.98 | 3.55 | 1.49E-05 | 0.0035 |

| piR-9540 | FR183841|DQ548429 | 7.75 | 55.99 | 3.55 | 9.25E-05 | 0.0063 |

| piR-37891 | FR023255|DQ576780 | 7.03 | 54.95 | 3.53 | 0.0002 | 0.0112 |

| piR-9541 | FR145409|DQ548430 | 8.54 | 61.79 | 3.51 | 9.51E-05 | 0.0063 |

| piR-2099 | FR270793|DQ540988 | 16.27 | 120.73 | 3.37 | 2.84E-05 | 0.0037 |

| piR-19514 | FR197620|DQ558403 | 12.33 | 79.67 | 3.29 | 0.0001 | 0.0085 |

| piR-58029 | FR288759|DQ596918 | 46.28 | 306.41 | 3.22 | 2.48E-05 | 0.0037 |

| piR-52354 | FR114547|DQ591243 | 48.82 | 302.85 | 3.10 | 3.94E-05 | 0.0040 |

| piR-52355 | FR068012|DQ591244 | 49.93 | 304.61 | 3.07 | 4.47E-05 | 0.0041 |

| piR-39894 | FR329966|DQ578783 | 57.78 | 324.96 | 3.06 | 8.19E-05 | 0.0063 |

| piR-54782 | FR145575|DQ593671 | 11.47 | 59.38 | 2.92 | 0.0025 | 0.0647 |

| piR-32444 | FR341794|DQ571333 | 9.97 | 54.20 | 2.89 | 0.0004 | 0.0198 |

| piR-57855 | FR271147|DQ596744 | 9.24 | 47.23 | 2.79 | 0.0007 | 0.0302 |

| piR-58593 | FR035643|DQ597482 | 10.47 | 46.72 | 2.79 | 0.0048 | 0.0959 |

| piR-1170 | FR002163|DQ540059 | 4.95 | 23.19 | 2.73 | 0.0012 | 0.0477 |

| piR-57916 | FR111727|DQ596805 | 31.38 | 134.02 | 2.67 | 0.0025 | 0.0649 |

| piR-56650 | FR219510|DQ595539 | 12.65 | 51.67 | 2.67 | 0.0017 | 0.0553 |

| piR-58508 | FR205116|DQ597397 | 7.70 | 46.88 | 2.66 | 0.0007 | 0.0302 |

| piR-1514 | FR086322|DQ540403 | 1042.43 | 4095.00 | 2.65 | 0.0015 | 0.0509 |

| piR-4018 | FR007806|DQ542907 | 6.67 | 32.63 | 2.64 | 0.0028 | 0.0713 |

| piR-43607 | FR138938|DQ582496 | 134.43 | 525.55 | 2.63 | 0.0019 | 0.0569 |

| piR-59374 | FR276112|DQ598263 | 84.58 | 419.95 | 2.61 | 3.25E-05 | 0.0037 |

| piR-1037 | FR325161|DQ539926 | 5.71 | 24.35 | 2.60 | 0.0018 | 0.0567 |

| piR-57649 | FR252389|DQ596538 | 11.56 | 54.73 | 2.60 | 0.0010 | 0.0300 |

| piR-75191 | FR279346|DQ614080 | 73.35 | 351.67 | 2.56 | 0.0043 | 0.0908 |

| piR-82944 | FR370156|DQ621833 | 498.41 | 1865.53 | 2.53 | 0.0020 | 0.0569 |

| piR-58507 | FR331389|DQ597396 | 7.03 | 38.70 | 2.49 | 0.0014 | 0.0507 |

| piR-32934 | FR163506|DQ571823 | 17.83 | 67.05 | 2.47 | 0.0029 | 0.0732 |

| piR-31923 | FR134050|DQ570812 | 17.75 | 77.92 | 2.46 | 0.0014 | 0.0507 |

| piR-32051 | FR383421|DQ570940 | 171.04 | 589.06 | 2.42 | 0.0037 | 0.0859 |

| piR-59127 | FR092662|DQ598016 | 31.24 | 161.07 | 2.25 | 0.0035 | 0.0821 |

| piR-72436 | FR198023|DQ611325 | 1165.30 | 7394.72 | 2.18 | 0.0018 | 0.0558 |

| piR-54043 | FR283482|DQ592932 | 77.64 | 261.96 | 2.09 | 0.0043 | 0.0908 |

| piR-2329 | FR080741|DQ541218 | 1502.17 | 4441.62 | 1.75 | 0.0043 | 0.0908 |

| piR-51518 | FR022075|DQ590407 | 37.59 | 6.66 | −2.20 | 0.0003 | 0.0143 |

| piR-46515 | FR270274|DQ585404 | 2.68 | 0.01 | −6.13 | 0.002438 | 0.0649 |

Ave, normalized average piRNA counts.

Bold piRNAs are discussed in detail in the text.

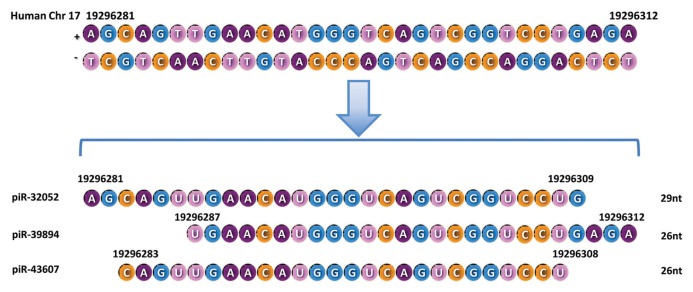

piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 Are Derived from the Same piRNA Cluster

Interestingly, we found that three piRNAs (piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607), which are upregulated in metastatic ccRCCs, are derived from the same piRNA cluster at chromosome 17. They are 29, 26 and 26 nucleotides in length, respectively, and their sequences are highly overlapping (Figure 1). This finding supports the nonphasing endonucleolytic processing pattern of piRNAs within a cluster sequence (6) and indicates that piRNAs derived from the same piRNA cluster (at least some of them with overlapping sequences) can have similar expression patterns.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal location, size and RNA sequences for piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607.

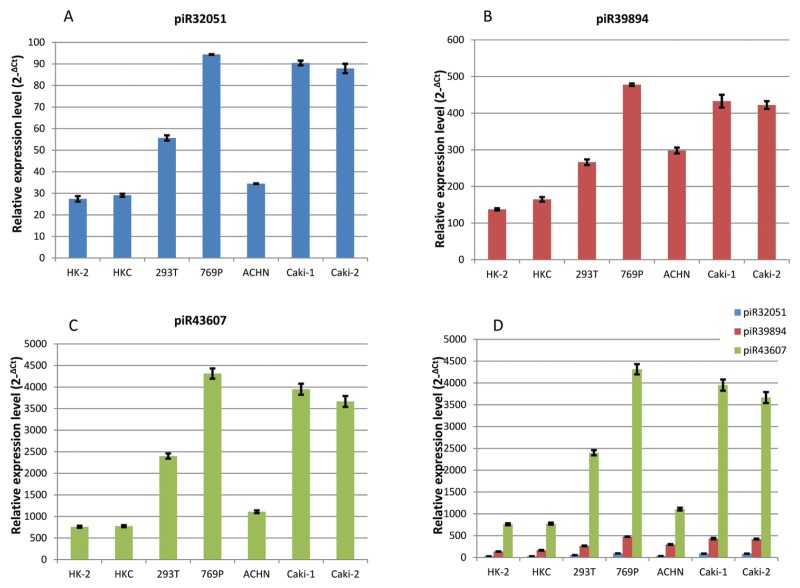

piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 Are Upregulated in Embryonic and Neoplastic Kidney Cell Lines and Are Not miRNAs or miRNA-Like sncRNAs

We first examined the expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 in benign (HK-2 and HKC), embryonic (HK293T) and neoplastic (ccRCC) (769P, ACHN, Caki-1 and Caki-2) renal epithelial cell lines. By small RNA qRT-PCR, piR-39894, piR-43607 and piR-32051 were found to be significantly overexpressed in embryonic renal and all ccRCC cell lines, as compared with the benign kidney cell lines (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative expression of piR-32051 (A), piR-39894 (B) and piR-43607 (C) in human benign kidney epithelial and embryonic renal and renal cell carcinoma cell lines by small RNA quantitative RT-PCR are shown. The comparison of the three piRNA expressions (D) is also shown. All expression levels were normalized with RUN6B. HK-2 and HKC, benign kidney epithelial cell lines; 239T, embryonic kidney epithelial cell line HEK293T; 769P, ACHN, Caki-1 and Caki-2, renal cell carcinoma cell lines.

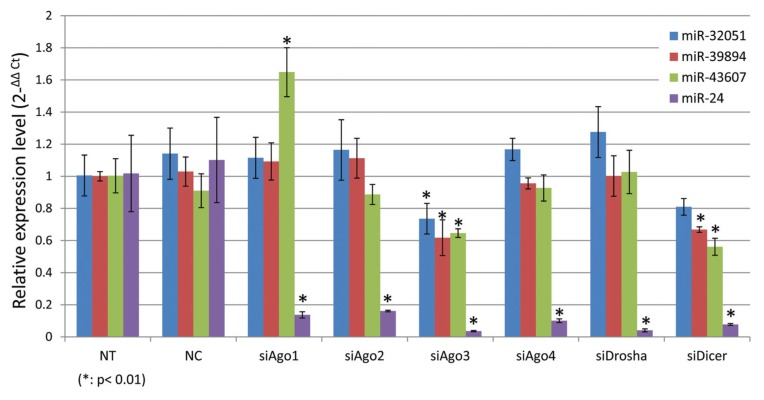

Because, by definition, piRNAs are independent of miRNA binding or processing proteins, we decided to examine the expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 in a ccRCC cell line ACHN when we introduced the siRNAs of Ago1, Ago2, Ago3, Ago4, Drosha and Dicer genes, respectively. The expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 was not significantly affected when Ago1, Ago2, Ago4 or Drosha was knocked down, and it was partially affected when Ago3 or Dicer was inhibited, while the expression of miR-24 was dramatically decreased. These findings indicate that piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 are not miRNAs or miRNA-like sncRNAs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relative expression (normalized with RNU6B and relative to NT) of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 in ACHN cells by small RNA quantitative RT-PCR when miRNA-related genes were knocked down. All expression levels shown were normalized with RUN6B and are relative to those of NT). NT, no treatment; siNC, transfected with scrambled anti-sense RNA molecules for negative control; siAgo1, siAgo2, siAgo3, siAgo4, siDrosha and siDicer, trans-fected with anti-Ago1, Ago2, Ago3, Ago4, Drosha and Dicer1 siRNA molecules, respectively.

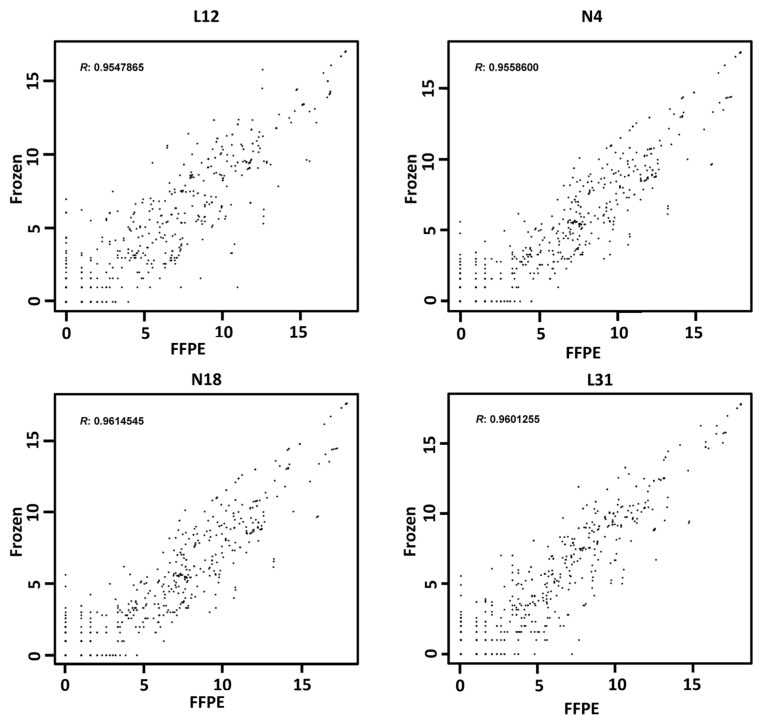

Concordance of piRNA Expression in Paired Frozen and FFPE Samples by Small RNA-seq Analysis

Probably because of protection from the Ago proteins, miRNAs are relatively stable in FFPE tissue. miRNA expression in paired frozen and FFPE tissue was found to be well correlated (14). Binding with Piwi proteins, piRNAs should be similarly stable in FFPE tissue. To prove this hypothesis, we have additionally performed small RNA-seq on paired FFPE benign kidney (n = 2) and ccRCC tissue (n = 2) (Supplementary Tables S4A, B). The comparison study showed that the piRNA expression in paired frozen and FFPE tissue was highly correlated (R = 0.95–0.96; Figure 4). This finding supports that piRNAs in FFPE tissue, similarly to miRNAs, are relatively stable and can be used to obtain reliable results in quantitative piRNA expression studies.

Figure 4.

Concordance of piRNA expression profiling between paired frozen and FFPE samples by deep sequencing. The piRNA expression of each frozen and FFPE sample pair was analyzed by deep sequencing. Log2-transformed expression levels were compared, and Pearson correlation was used to calculate the similarity between the each pair of samples. L12 and L31, ccRCC; N4 and N18, benign kidney samples.

Aberrant Expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 Is Highly Associated with ccRCC Metastasis, as Validated in the 68-Specimen FFPE Tissue Cohort

To validate the findings in our initial cohort study by small RNA-seq, we measured the expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 in cohort 2, the 68-sample FFPE ccRCC cohort, by performing small RNA qRT-PCR with customized TaqMan primers and probes. We used the expression of miR-24, one of the most stably expressed miRNAs in benign and neoplastic kidney tissue, for normalization (15). We also examined whether these piRNAs were associated with clinicopathological variables. We found that piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 were significantly upregulated in metastatic ccRCCs and primary ccRCCs, which concurrently presented with metastasis, as compared with the localized counterparts (P < 0.001), which confirmed our small RNA-seq results (Table 4). In addition, we found the significant overexpression of the three piRNAs in late-stage (stage IV) tumors compared with early-stage tumors (stages I and II) (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that the higher expression of the three piRNAs was also significantly correlated with ccRCC patients’ cancer-specific survival (P < 0.01) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Upregulated piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 expression in high stage and metastatic ccRCC.a

| ID | Stages/metastatic status | Log2 ratio | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| piR-32051 | |||

| Stages I–II versus stage III | 1.61 | 0.127 | |

| Stages I–II versus stage IV | 2.64 | 0.0005 | |

| Stage III versus stage IV | 1.03 | 0.3927 | |

| Localized versus metastatic | 2.07 | 0.0007 | |

| piR-39894 | |||

| Stages I–II versus stage III | 1.76 | 0.0974 | |

| Stages I–II versus stage IV | 3.06 | <0.0001 | |

| Stage III versus IV | 1.29 | 0.2553 | |

| Localized versus metastatic | 2.53 | <0.0001 | |

| piR-43607 | |||

| Stages I–II versus stage III | 1.85 | 0.0562 | |

| Stages I–II versus IV | 2.95 | <0.0001 | |

| Stage III versus IV | 1.09 | 0.3308 | |

| Localized versus metastatic | 2.72 | 0.0001 | |

n = 68.

Table 5.

Univariate Cox regression analysis: upregulated expressions of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 correlate with prognosis of clear renal cell carcinoma patients.

| ID | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | |||

|

| |||

| piR-32051 | 1.13 | 1.001–1.272 | 0.0540 |

| piR-39894 | 1.15 | 1.022–1.297 | 0.0238 |

| piR-43607 | 1.16 | 1.027–1.319 | 0.0201 |

|

| |||

| Cancer-specific survival | |||

|

| |||

| piR-32051 | 1.21 | 1.054–1.390 | 0.0081 |

| piR-39894 | 1.23 | 1.078–1.422 | 0.0032 |

| piR-43607 | 1.24 | 1.082–1.445 | 0.0031 |

DISCUSSION

piRNA was previously considered to be germline specific (17). These endogenous sncRNAs act as guardians to protect the integrity of the genome from invasive TEs in the germline. In addition to the characteristic function of the silencing of mobile elements by target slicing, piRNA function of mRNA regulation, and mechanisms of transcriptional gene silencing and mRNA deadenylation, are also described (7). Recently, studies have demonstrated that piRNAs are widely present and play important roles in somatic cells (8). However, piRNAs have not been thoroughly studied in cancers (17). A few recent studies have begun to show that piRNAs are differentially expressed in human cancers and their benign counterparts. In HeLa cells, piR-NAs, along with HILI protein, were found to play a role in LINE1 suppression (11). In gastric cancer tissue, piR-651 and piR-823 were found to be dysregulated (12,13). Specifically, the upregulation of piR-651 is associated with the clinical stage of gastric cancer. In breast cancer, piR-4987, piR-20365, piR-20485 and piR-20582 were found to be overexpressed, and the expression level of piR-4987 was associated with lymph node metastasis (18). These dysregulated piR-NAs may play important roles in tumorigenesis in previously unsuspected ways and have potential implications in cancer detection, classification and therapy (19).

In this study, we are the first to demonstrate that piRNAs are present in benign and neoplastic kidney tissue and cell lines. By small RNA-seq analysis of the frozen ccRCC tissue cohort, we found that piRNAs were differentially expressed in benign kidney tissue and localized and metastatic ccRCCs. By real-time PCR, we validated the aberrant expression of three selected piRNAs (piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607) in ccRCC cells (769P, ACHN, Caki-1 and Caki-2), as well as embryonic (HK293T) renal epithelial cells, as compared with benign (HK-2 and HKC) epithelial cells. By using a 68-specimen FFPE tissue cohort, we further validated that the upregulation of the three selected piRNAs was significantly associated with ccRCC metastasis. Furthermore, we demonstrated that their expression was significantly correlated with late ccRCC stage and patients’ cancer-specific survival. These findings may help in understanding the mechanisms of ccRCC metastasis and progression. In addition, these piR-NAs may potentially serve as prognostic molecular biomarkers to guide more appropriate clinical treatment.

By definition, piRNAs are Piwi protein interacting and do not depend on miRNA binding and processing proteins. Most piRNAs currently documented in piRNA banks were originally discovered because of their interaction/binding with one of the Piwi proteins. However, sncRNAs that bind to Piwi proteins are not necessarily true piRNAs. Our recent study (unpublished data) showed that up to 70% of sncRNAs coimmunoprecipitated with overexpressed Piwi proteins are mature miRNAs. Therefore, it is important to rule out the possibility that the three selected piRNAs are miRNAs or miRNA-like sncRNAs that cobind with Piwi proteins. We examined the expression of piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 in the ccRCC cell line ACHN when Ago1, Ago2, Ago3, Ago4, Drosha and Dicer genes were knocked down individually. Our findings (Figure 3) indicate that the three piRNAs were independent of the miRNA binding and processing proteins Ago1, Ago2, Ago4 and Drosha. Although the expression of these piRNAs was partially affected when the Ago3 or Dicer gene was inhibited, the decreases in these piRNAs were much less than those in miRNA (miR-24). Ago3 was known to be associated with miRNAs in mammals (4). In flies, piRNAs for a specific group of transposons are Ago3-dependent (20). This finding might explain why piRNA expression was partially affected by Ago3 inhibition. The reason for this partial decrease of the piRNAs due to Dicer gene inhibition is not clear. It is probably due to a global decrease of miRNAs secondary to the knockdown of the Dicer gene.

piRNAs are reported to have hundreds of thousands of individual types (21–23). Among the large number of piRNA sequences obtained from each genotype, the vast majority of the piRNA sequences are found only once (20). There were approximately 27,000 known distinct types of piRNAs identified in the 24 samples, but only 920 (~3.4%) were shown to have two or more copies in at least one specimen. This finding supports the belief that piRNA sequences have extremely high complexity (20). Most piRNAs are found to be derived from a relatively small number of genomic regions called piRNA clusters in chromosomes (6). Because their precursors are linear single-stranded RNAs and do not have stem-loop–like secondary structures, piRNAs do not show any phasing (equally periodic) endonucleolytic processing patterns within a cluster sequence, and their sequences can overlap with each other (6). This characteristic feature was seen in the current study. piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 are derived from the same piRNA cluster at chromosome 17 with overlapping sequences. Our study is the first to show that piRNAs derived from the same piRNA cluster can have similar dysregulated expression patterns in cancer cells.

As mentioned above, recently independent studies have shown that piRNAs are involved in cancer development and may play oncogenic or tumor suppressor roles (19). In cancer cells, piRNAs may be involved in cell proliferation (viability) and invasion (19). In this study, while we introduced one of the anti–piR-32051, anti-39894 or anti–piR-43607 LNA molecules into metastatic ccRCC cells (ACHN cell line) at a time, we did not observe a significant decrease in cancer cell proliferation (data not shown). A wound healing assay performed by introducing anti–piR-43607 LNA molecules into ACHN cells has shown only minimal inhibition in cell migration (data not shown). Most likely, inhibition of one of the three piRNAs at a time may not be sufficient enough to block the process of proliferation or migration in one cell line. Future studies to explore mechanisms or functional significance of the three piRNAs in ccRCC progression and metastasis should be considered.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that piRNAs are present in human kidney tissue and cell lines and are differentially expressed in benign kidney tissue and localized and metastatic ccRCCs. We identified that piR-32051, piR-39894 and piR-43607 are derived from the same piRNA cluster, and their overexpression is significantly associated with ccRCCs of high tumor stage and metastasis and patients’ cancer-specific survival. Further study of these piRNAs may help to understand the mechanisms of ccRCC metastasis and progression specifically associated with novel piRNAs. It may also broaden our views of the biologic significance of piRNAs in human cancer and cancer metastasis. These specific piRNAs may serve as biomarkers as well for ccRCC diagnosis, subclassification, early metastasis detection and clinical outcome.

Supplemental Data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Beckman Research Institute of COH and California Cancer Specialists Medical Group. This work was also partly funded by the 2013 COHNMC Department Chairs Discretionary Funds and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81072155). The authors thank Joo Song and Massimo D’Apuzzo at the COHNMC Department of Pathology for their help.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

Cite this article as: Li Y, et al. (2015) Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are dysregulated in renal cell carcinoma and associated with tumor metastasis and cancer-specific survival. Mol. Med. 21:381–8.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8–31. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czech B, Hannon GJ. Small RNA sorting: matchmaking for Argonautes. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–39. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf W. Biogenesis and germline functions of piRNAs. Development. 2008;135:3–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:246–58. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weick EM, Miska EA. piRNAs: from biogenesis to function. Development. 2014;141:3458–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.094037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan Z, et al. Widespread expression of piRNA-like molecules in somatic tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6596–6607. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamore PD. Somatic piRNA biogenesis. EMBO J. 2010;29:3219–3221. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee EJ, et al. Identification of piRNAs in the central nervous system. RNA. 2011;17:1090–1099. doi: 10.1261/rna.2565011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, et al. Identification of piRNAs in Hela cells by massive parallel sequencing. BMB Rep. 2010;43:635–41. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.9.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng J, et al. piR-823, a novel non-coding small RNA, demonstrates in vitro and in vivo tumor suppressive activity in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;315:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng J, et al. piRNA, the new non-coding RNA, is aberrantly expressed in human cancer cells. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:1621–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng L, et al. MicroRNA profiling of clear cell renal cell carcinoma by whole-genome small RNA deep sequencing of paired frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. J Pathol. 2010;222:41–51. doi: 10.1002/path.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, et al. Identification of a 4-microRNA signature for clear cell renal cell carcinoma metastasis and prognosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang KC, et al. RNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of mammalian non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D178–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishizu H, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Biology of PIWI-interacting RNAs: new insights into biogenesis and function inside and outside of germlines. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2361–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.203786.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang G, et al. Altered expression of piRNAs and their relation with clinicopathologic features of breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:563–8. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mei Y, Clark D, Mao L. Novel dimensions of piRNAs in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;336:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C, et al. Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell. 2009;137:509–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aravin A, et al. A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes. Nature. 2006;442:203–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature04917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennecke J, et al. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:1089–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.