Abstract

Currently, impacts of exposure to TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) on the cardiovascular system are not well understood. The aim of this study was to investigate whether TiO2 NPs induce myocarditis and its underlying molecular mechanism in the cardiac inflammation in mice. Mice were exposed to TiO2 NPs for 6 months; biochemical parameters of serum and expression of Th1-related and Th2-related cytokines in the heart were investigated. The results showed that TiO2 NP exposure resulted in cardiac lesions coupling with pulmonary inflammation; increases of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatine kinase (CK), C-reaction protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alpha-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (HBDH), adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) levels; and a reduction of nitric oxide (NOx) level in the serum. These were associated with increases of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-4, IL-6, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), creatine kinase, CRP, adhesion molecule-1, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)1, STAT3, or STAT6, GATA-binding domain-3, GATA-binding domain-4, endothelin-1 expression levels, and T-box expressed in T cells expression level that is the master regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokines and transcription factors in the heart. These findings imply that TiO2 NP exposure may increase the occurrence and development of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Titanium dioxide nanoparticles, Heart, Inflammation, Inflammatory cytokines, Transcription factors

Background

Nanotechnology or nanomaterial applications have caused large impacts on human daily life. However, the exposure of workers, consumers, and susceptible groups should be of high concern due to nanomaterial production or uses. Especially, cardiovascular effects due to nanoparticle (NP) exposure may be a possible health risk [1–3]. The mechanisms of these hazardous effects are involved in oxidative stress, inflammation, vasomotor dysfunction, neuronal signaling, and possible translocation of NPs from the airways to the circulation [3]. Inhaled NPs were demonstrated to enter the lungs where they are translocated to the circulatory system, leading to cardiovascular lesions [4]. TiO2 NPs are widely applied in an increasing number of products including paints, cosmetics, sunscreen, medicine, food, and toothpaste, and in environmental decontamination, etc. [5–10]. However, previous studies demonstrated that TiO2 NP exposure resulted in titanium accumulation in the heart, myocardium dysfunction, oxidative stress, cardiac inflammation, and atherosclerosis in mice [11–13]; increased plaque progression in aorta in mice [14]; and induced endothelial inflammatory response in primary vascular endothelial cells [15]. Other NP exposure, such as ZnO NPs, was also suggested to induce cardiac infarction in rats [16]. However, whether NP exposure is associated with alterations of cytokine response and immune effectors, and imbalance of Th1-related and Th2-related cytokines in cardiovascular damages remains unclear.

As suggested, myocarditis is closely involved in the progression of heart failure due to chronically environmental stimuli such as inhaled particles [5, 7]. Studies showed that inhaled NPs are not reserved in the lung but enter the blood circulation and distribute to distant organs including the liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, and heart [17–19]. Therefore, we hypothesized that NP exposure may give rise to various venenous stimuli that cause secretion of both leukocyte soluble adhesion molecules, facilitating the attachment of monocytes to endothelial cells, and chemokines, thus resulting in the monocytes’ migration into the subintimal space. The transformation of monocytes into macrophages led to myocarditis in animals and humans. The pathophysiological changes provide potential targets for identifying and monitoring the NP-induced inflammatory process, while potential targets are involved in pro-inflammatory risk factors such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and inflammatory stimuli [20]. Thus, it is necessary to confirm the mechanism of NP-induced myocarditis.

In this study, therefore, myocardium parameters and alterations in the inflammatory cytokines and transcription factor expression in mouse heart were investigated to determine whether TiO2 NP-induced cardiac lesion is mediated by Th1-related and Th2-related cytokines in mice.

Methods

Chemicals

For the preparation, characteristics of anatase TiO2 NPs have been described in our previous work [21–23]. Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC) 0.5 % w/v was employed as an agent for suspending diffusion. TiO2 powder was dispersed onto the surface of 0.5 % w/v HPMC solution, and then the suspending solutions containing TiO2 particles were treated ultrasonically for 15–20 min and mechanically vibrated for 2 or 3 min [22, 23]. The particle sizes of NPs suspended in 0.5 % w/v HPMC solution following incubation (5 mg/L) were determined using a TecnaiG220 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (FEI Co., USA) operating at 100 kV, respectively. The surface area of sample was detected by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) adsorption measurements on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020M+ C instrument (Micromeritics Co., USA). The average aggregate or agglomerate size of the TiO2 NPs in 0.5 % (w/v) HPMC solution (5 mg/mL) was determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zeta PALS + BI-90 Plus (Brookhaven Instruments Corp., USA) at a wavelength of 659 nm [22, 23]. The characteristics were about 5.5 nm for average particle size, 174.8 m2/g for the surface area, mainly 294 nm for the mean hydrodynamic diameter, and 9.28 mV for the ζ potential [21–23].

Ethics Statement

All experiments were approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Soochow University (Grant 2111270) and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Guidelines).

Animals and Treatment

One hundred sixty 4-week-old CD-1 (ICR) male mice (20 ± 2 g body weight) were purchased from the Animal Center of Soochow University (China). Immediately after arrival, all mice were weighed and randomly allocated into four subgroups (n = 40), including a control group treated with 0.5 % w/v HPMC and three experimental groups treated with 1.25, 2.5, and 5 mg/kg TiO2 NPs [24], respectively. For dose selection, we consulted a report of the World Health Organization from 1969. According to the report, the LD 50 of TiO2 for rats is >12 g/kg body weight after oral administration. We also consulted that in November 2005, the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) proposed a recommended exposure limit (REL) for TiO2 NPs at 0.3 mg/m3 (NIOSH). In Japan, the acceptable exposure concentration of TiO2 NPs was estimated to be 1.2 mg/m3 as a time weighted average (TWA) for an 8-h workday and a 40-h workweek [25, 26]. In Europe, food-grade TiO2 is approximately 36 % of the TiO2 NPs that are smaller than 100 nm in at least one dimension, this exposure limit decreases to approximately 0.1 mg TiO2/person/day of nanoscale TiO2 [27]. Mice were housed in cages and were kept under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Room environment was set up at 24 ± 2 °C with 60 ± 10 % of relative humidity and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Distilled water and sterilized food for mice were available ad libitum. They were acclimatized and quarantined to this environment for 5 days prior to dosing.

Before the nasal instillation to the mice, TiO2 NP powder was dispersed onto the surface of 0.5 % w/v HPMC and re-suspended TiO2 NPs were homogenized by a sonicator for 30 min and mechanically vibrated for 5 min. The volume of TiO2 NP suspensions was calculated for each mouse after weighing mice and was administered to the mice by nasal administration every other day for 6 months. After the final exposure to TiO2 NPs (e.g., 24 h following the last exposure), all the mice were sacrificed after anesthetization with ether. Blood sera were collected and stored at −20 °C before use. Every effort was made to minimize animal suffering in each experiment. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles in the Use of Animals in Toxicology.

Assay of Pulmonary Inflammation

After blood collection, the lungs from the control and TiO2 NP-treated groups were immediately lavaged twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). An average of >90 % of the total instilled PBS volume was retrieved both times, and the amounts did not differ among the groups. The resulting fluid was centrifuged at 400×g for 10 min at 4 °C to separate the cells from the supernatant containing various surfactants and enzymes. The cell pellet was used for enumeration of total and differential cell counts as described by AshaRani et al [28]. Macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils recovered from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were counted using dark field microscopy to examine the extent of phagocytosis. The inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were detected in the primary cell-free BALF by ELISA commercial kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Histopathological Examination of Lung and Heart

Lungs or hearts were fixed with 10 % neutral buffered formalin for 3 days, which were embedded in paraffin blocks, sliced to 5-μm thickness, placed on separate glass slides, and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). After H&E staining, the sections were evaluated by blinding test, using an optical microscope (U-III Multi-point Sensor System; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Biochemical Assay of Myocardium Function

In the present study, the activities of aminotransferase (AST), creatine kinase (CK), cross-reaction protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and alpha-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (HBDH) in the serum were determined using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Levels of eotaxin (ET)-1, total nitric oxide (nitrite + nitrate, NOx), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in the serum was assayed for evaluating myocardium function using commercial kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Assay of Cytokine Expression

Total RNA was extracted from individual heart using Tripure Isolation Reagent (Roche, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Probes and cycling condition were optimized in accordance with MIQE guidelines for PCR [29]. cDNA was used for the real-time PCR by employing primers designed using Primer Express Software according to the software guidelines. PCR primers used in the gene expression analysis are listed in Table 1. Gene expression levels were calculated as a ratio to the expression of the reference gene, GAPDH, and data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method. The probes for NF-κB, IκB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, CRP, CK, TGF-β, IFN-γ, VCAM-1, MCP-1, STAT1, STAT3, STAT6, GATA3, GATA4, T-bet, and VEGF were designed by the manufacturer and purchased from Shinegene Company (Shanghai, China). The RT-qPCR data were processed with the sequence detection software version 1.3.1 following the method of Schefe et al. [30].

Table 1.

Real-time PCR primer pairs. PCR primers used in the gene expression analysis

| Gene name | Description | Primer sequence | Primer size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refer-GAPDH | mGAPDH-F | 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3′ | |

| mGAPDH-R | 5′-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG-3′ | 150 | |

| CK | mck-F | 5′-GAGATCTTCAAGAAGGCTGGTCA-3′ | |

| mck-R | 5′-GAGATGTCGAACACGGCG-3′ | 227 | |

| CRP | mcrp-F | 5′-GCGGAAAAGTCTG-CACAAGG-3 | |

| mcrp-R | 5′-GGAGATAGCACAAAGTCCCACAT-3 | 153 | |

| ET-1 | mET-1-F | 5′-AGACCACAGACCAAGGGAACA-3′ | |

| mET-1-R | 5′-TCTGCTTGGCAGAAATTCCA-3′ | 392 | |

| ICAM-1 | mICAM-1-F | 5′-AGACACAAGCAAGAGAAGAAAAGG-3′ | |

| mICAM-1-R | 5′-TTGGGAACAAAGGTAGGAATGTAT-3′ | 425 | |

| MCP-1 | mMCP-1-F | 5′-GCTGACCCCAAGAAGGAATG-3′ | |

| mMCP-1-R | 5′-TTGAGGTGGTTGTGGAAAAGG-3′ | 184 | |

| NF-κB | mNF-κB-F | 5′-GTGGAGGCATGTTCGGTAGTG-3′ | |

| mN-κB-R | 5′-TCTTGGCACAATCTTTAGGGC-3′ | 195 | |

| IκB | mIκB-F | 5’-GGTGCAGGAGTGTTGGTGG-3′ | |

| mIκB-R | 5′-TGGCTGGTGTCTGGGGTAC-3′ | 173 | |

| IL-1β | m IL-1β-F | 5′-GCTTCAGGCAGGCAGTATCA-3′ | |

| mIL-1β-R | 5′-TGCAGTTGTCTAATGGGAACG-3′ | 196 | |

| TNF-α | mTNF-α-F | 5′-CCCTCCAGAAAAGACACCATG-3′ | |

| mTNF-α-R | 5′-CACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAGACAG-3′ | 183 | |

| TGF-β | mCcl21a-F | 5′-CACGGTCCAACTCACAGGC-3′ | |

| mCcl21a-R | 5′-TTGAAGCAGGGCAAGGGT-3′ | 102 | |

| IL-4 | mIL-4-F | 5′-TGTAGGGCTTCCAAGGTGCT-3′ | |

| mIL-4-R | 5′-TGATGCTCTTTAGGCTTTCCAG-3′ | 199 | |

| IL-6 | mIL-6-F | 5′-GGGACTGATGCTGGTGACAAC-3′ | |

| mIL-6-R | 5′-CAACTCTTTTCTCATTTCCACGA-3′ | 163 | |

| STAT1 | mSTAT1-F | 5′-ACGCTGCCTATGATGTCTCG-3′ | |

| mSTAT1-R | 5′-ACGGGATCTTCTTGGAAGTTATC-3′ | 163 | |

| STAT3 | mSTAT3-F | 5′-TGACCAATAACCCCAAGAACG-3′ | |

| mSTAT3-R | 5′-TGACACCCTGAGTAGTTCACACC-3′ | 181 | |

| STAT6 | mSTAT6-F | 5′-AGCATCTTGCCGCACATCA-3′ | |

| mSTAT6-R | 5′-GGCAGGTGGCGGAACTCT-3′ | 128 | |

| GATA3 | mGATA3-F | 5′-CCACGGGAGCCAGGTATG-3′ | |

| mGATA3-R | 5′-CGGAGGGTAAACGGACAGAG-3′ | 169 | |

| GATA 4 | mGata4-F | 5′-CCTGGAAGACACCCCAATCT-3′ | |

| mGata4-R | 5′-GGTAGTGTCCCGTCCCATCT-3′ | 115 | |

| T-bet | mT-bet-F | 5′-TGGACCCAACTGTCAACTGC-3′ | |

| mT-bet-R | 5′-CTCGGAACTCCGCTTCATAAC-3′ | 173 |

To determine protein levels of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), IκB, TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-4, and IL-6, CRP, CK, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), ICAM-1, MCP-1, signal transducers and activators of transcription factor (STAT)1, STAT3, and STAT6, GATA3, GATA4, ET-1, T-box expressed in T cell (T-bet), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the heart (n = 5 each), total protein from the frozen heart tissues (n = 5 in each group) from experimental and control mice was extracted using Cell Lysis Kits (GENMED SCIENTIFICS INC.USA) and quantified using BCA protein assay kits (GENMED SCIENTIFICS INC.USA). ELISA was performed using commercial kits that were selective for each respective protein (R&D Systems, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Data were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 19.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA), and statistical comparisons were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. Differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was less than 0.05.

Results

Pulmonary or Heart Inflammation

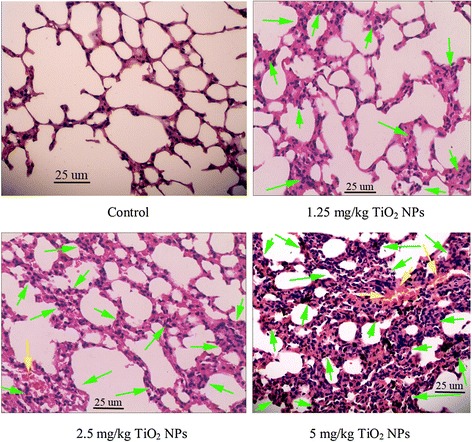

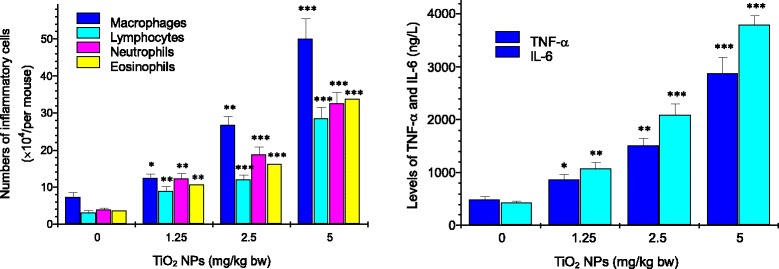

Figure 1 exhibits thickening of the alveolar septae, bleeding, and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the TiO2 NP-treated mouse lungs. In addition, significant black agglomerates were observed in the lung samples exposed to 5 mg/kg of TiO2 NPs (Fig. 1). Confocal Raman microscopy further suggested that the black agglomerate was due to the deposition of TiO2 NPs in the lungs [31]. With increasing TiO2 NP dose, the numbers of inflammatory cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils and the levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in the BALF were greatly elevated as compared to the control (Fig. 2, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Histopathological observation of lungs of mice after nasal administration of TiO2 NPs for 6 months (n = 5). TiO2 NP-exposed mice show infiltration of inflammatory cells (green arrow) and bleeding (yellow arrow) in the lung

Fig. 2.

Numbers of inflammatory cells and levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in BALF. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Values represent means ± SD (n = 5)

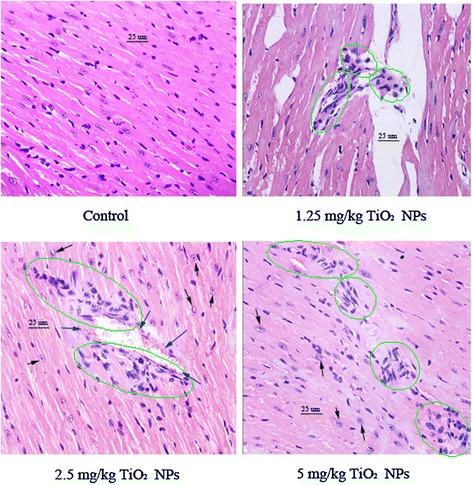

The histological examinations of the heart sections are shown in Fig. 3. Unexposed heart samples exhibited normal architecture (Fig. 3), whereas those from mice exposed to increasing TiO2 NP dose presented severe pathological changes, including infiltration of inflammatory cells, myocardial cells swelling, sparse cardiac muscle fibers, and disorder of muscle cell array (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Histopathological observation of hearts after nasal administration of TiO2 NPs for 6 months (n = 5). Black arrow indicates myocardial cells swelling; green circle indicates infiltration of inflammatory cells; blue arrow indicates hemolysis or bleeding

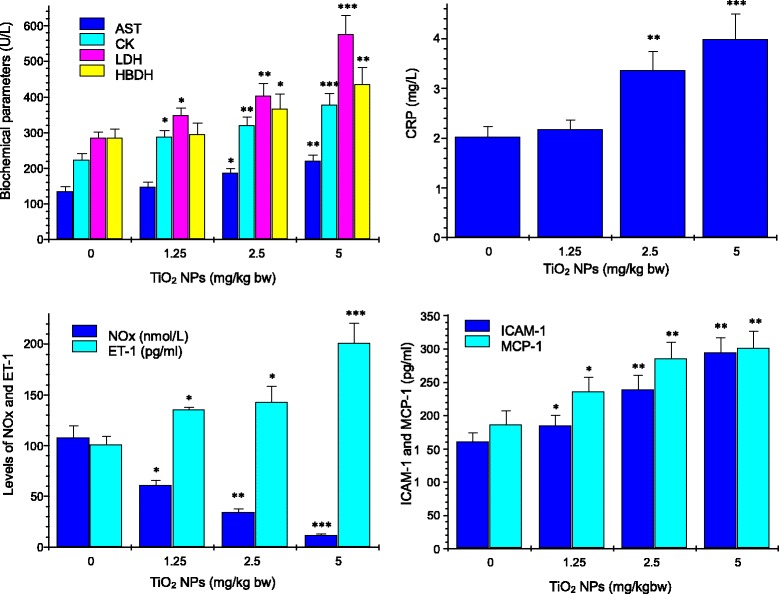

Biochemical Parameters

The changes of biochemical parameters in the serum induced by TiO2 NP exposure are presented in Fig. 4. With increasing TiO2 NP dose, inflammatory parameters, including AST, CK, CRP, LDH, HBDH, ICAM-1, and MCP-1, increased gradually (P < 0.05). These results indicated that chronic TiO2 NP exposure made serious cardiac inflammation of mice. ET-1 and NOx were determined in mice to evaluate vascular endothelial function after TiO2 NP exposure. Figure 4 lists the levels of ET-1 and NOx in the serum, showing an increase of ET-1 level (P < 0.05) and a decrease of NOx level (P < 0.05). It indicated that TiO2 NP-exposed mice had an endothelial dysfunction.

Fig. 4.

Effect of TiO2 NPs on biochemical parameters in the serum of myocardium after nasal administration with TiO2 NPs for 6 months. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Values represent means ± SD (n = 5)

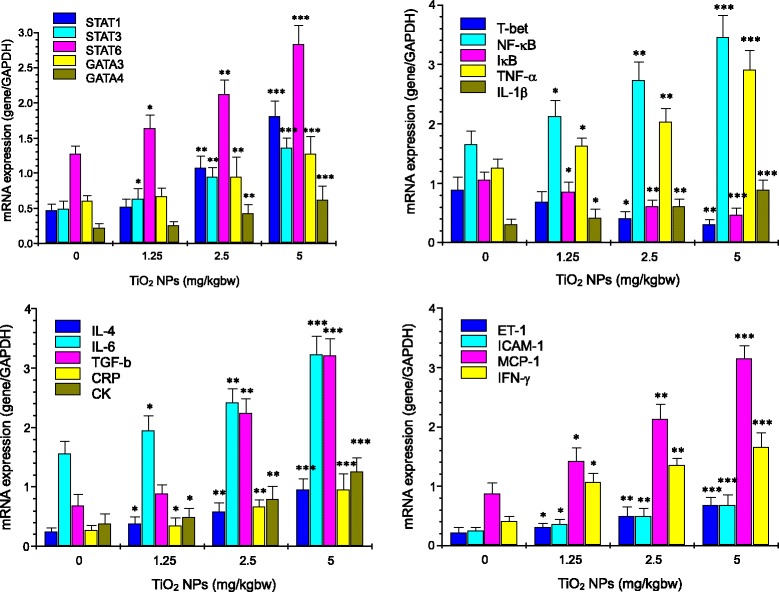

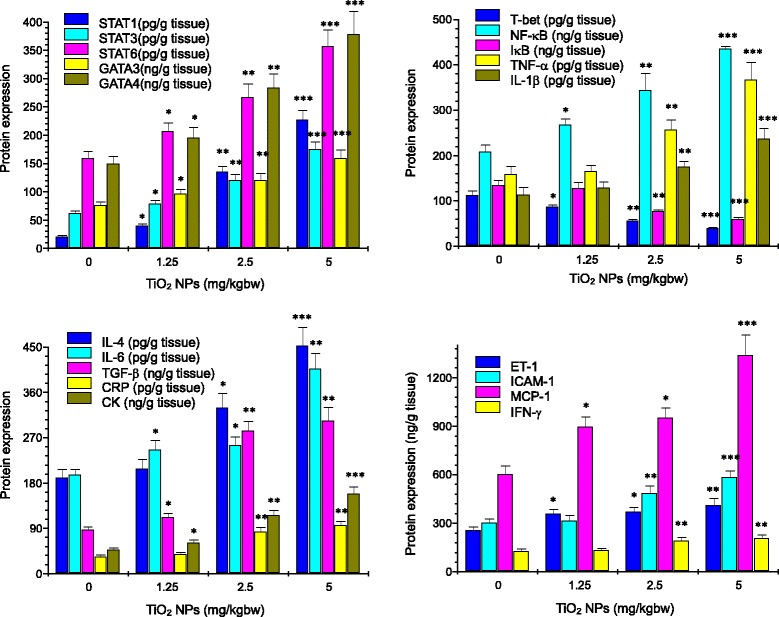

Expression of Th1 and Th2 Cytokine mRNA and Proteins

To further confirm whether TiO2 NP exposure resulted in imbalance of Th1-related and Th2-related cytokines, including NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, CK, CRP, ET-1, TGF-β, IFN-γ, ICAM-1, MCP-1, STAT1, STAT3, STAT6, T-bet, GATA3, and GATA4, in the TiO2 NP-induced cardiac injury, changes of the cytokine gene and protein expression in mouse heart were examined and are showed in Figs. 5 and 6. Mice with TiO2-NP-induced cardiac damages presented with a significant, dose-dependent reduction in the nuclear IκB expression and a dose-dependent marked increase in expression of these genes and proteins mentioned above in the cardiac tissue (Figs. 5 and 6, P < 0.05). These findings pointed to the imbalance of Th1-related and Th2-related cytokines in mice following exposure to TiO2 NPs.

Fig. 5.

Effect of TiO2 NPs on mRNA expression of myocarditis-related genes in mouse heart by real-time PCR analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Values represent means ± SD (n = 5)

Fig. 6.

Effect of TiO2 NPs on protein expression of myocarditis-related genes in mouse heart by ELISA analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Values represent means ± SD (n = 5)

Discussion

Manufactured NPs have been suggested to increase the risk and incidence of cardiovascular diseases such as myocarditis [5, 17, 18, 31, 32]. Occupational and environmental exposure of TiO2 NPs may be one of risk factors for increased myocarditis in humans. Air dust containing TiO2 NPs may result in higher inhalation absorption and subsequent translocation of TiO2 NPs into the circulatory system. Seaton et al. indicated that inhaled particles act as their cardiovascular effects indirectly through the passage of inflammatory mediators from the lung to the systemic circulation [33]. In the present study, TiO2 NP exposure led to a severe pulmonary inflammation characterized by infiltration of macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils into the airways (Figs. 1 and 2), especially, there was a close association with level of pulmonary inflammation and the cardiac damages such as myocarditis and myocardial cell swelling (Fig. 3). Levels of TNF-α and IL-6 proteins in the BALF were elevated due to TiO2 NP exposure (Fig. 2), which were associated with pulmonary inflammation (Figs. 1 and 2). It implies that the inflammatory pathways may be likely to contribute to the cardiovascular effects of TiO2 NPs, neither pulmonary nor systemic inflammation alone can account for the myocarditis actions of TiO2 NPs. To confirm mechanism of the cardiac lesions of mice following exposure to TiO2 NPs, in this study, we examined alterations of different serum parameters and expression of Th1-related and Th2-related cytokines, and the results are discussed as follows.

The cardiac lesions due to TiO2 NP exposure were reflected to severe myocardium biochemical dysfunction, marked by significant increases of AST, CK, LDH, CRP, HBDH, ICAM-1, and MCP-1 levels, and NOx reduction in the serum (Fig. 4). Our previous study has also indicated that intragastric administration of TiO2 NPs for 90 days resulted in increased CK activity and severe pathological changes of heart in mice such as inflammation [12]. Elevated levels of biomarkers involving systemic inflammation, immune function, and ventricular remodeling, including AST, LDH, CRP, CK, HBDH, TNF-α, ET-1, ICAM-1, and MCP-1, also have been related to morbidity and mortality among heart failure patients [34–37]. The expression of adhesion molecules such as MCP-1 and ICAM-1 is associated with early atherosclerotic formation [38]. Importantly, increased ICAM-1 expression exacerbated the inflammatory process via facilitating leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium and releasing activated leukocytes to the inflammatory sites [39]. In our study, increased levels of AST, LDH, CRP, CK, HBDH, TNF-α, ICAM-1, and MCP-1 in the serum and tissue mRNA and protein expression by TiO2 NP exposure may be associated with inflammatory responses in the heart. Increased AST and CRP were demonstrated to be closely involved in the liver lesions of mice due to TiO2 NP exposure [13, 23].

As suggested and mentioned above, endothelial dysfunction after exposure to TiO2 NPs may be related to susceptibility of mice. In the present study, our data showed that the NOx level in the serum in the TiO2 NP-exposed mice was significantly decreased (Fig. 4), whereas ET-1 concentration in the serum and ET-1 expression in the heart were markedly elevated (Figs. 4, 5, and 6). It is well known that NO is very important for endothelial function and the dysfunction exacerbated cardiovascular lesions [40]. In addition, NO is also demonstrated to decrease inflammation [41] and platelet adhesion [42, 43]. Excessive endothelium-restricted ET-1 expression in mice can not only cause endothelial dysfunction but also impair NOx-dependent vasorelaxation in resistance vessels and intensify vascular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [44]. Our findings showed that TiO2 NP-exposed mice exhibited severe inflammation and vascular endothelial dysfunction, implying that the lesions may be involved in NOx reduction and ET-1 overexpression due to TiO2 NP exposure.

TGF-β can promote the synthesis of various cytokines and growth factors that are involved in the formation of cardiac fibrosis and mediate the transition from acute inflammation to fibrosis in ischemic heart disease [45]. Resolution of inflammation and progressive remodeling are suggested to be involved in TGF-β overexpression in the myocardium [46–51]. In our study, therefore, TGF-β expression was analyzed by RT-PCR and ELISA, showing that TiO2 NP exposure significantly upregulated expression of TGF-β in mouse heart (Figs. 5 and 6) coupling with myocardial cell swollen and increased inflammatory cells in mice (Fig. 3). It is likely that TiO2 NP-induced hypertrophic myocardium may involve in TGF-β overexpression in mice.

Myocarditis is suggested to be a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease. Activated T cells can release numerous chemokines and cytokines, recruiting and activating other inflammatory cells (such as macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells) [52]. Overexpression of cytokines induced by inflammatory stimuli exacerbates the progression of myocardial damage in patients with myocarditis [51]. Immunological and pathophysiological events remarkably contribute to increase mast cells [53], resulting in cardiac inflammation and fibrosis [54]. IL-1 is considered to play a critical role and is highly expressed in hearts with myocarditis [55]. Therefore, it is important to decrease myocarditis via decreasing expression of inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β and TNF-α) and a master transcriptional factor NF-κB that can modulate many genes responsible for both the innate and adaptive immune response. In the present study, TiO2 NP exposure resulted in myocardial cells swelling and infiltration of inflammatory cells in mouse heart (Fig. 3), which were associated with increased expression of NF-κB, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the TiO2 NP-exposed heart (Figs. 5 and 6). Furthermore, the gene and protein expression of Th1- and Th2-related cytokines including IL-4, IL-6, and IFN-γ was significantly increased in the TiO2 NP-exposed mouse heart (Figs. 5 and 6). Additionally, TiO2 NP exposure induced marked upregulation of Th2-related transcription factors including STAT1, STAT3, STAT6, GATA3, and GATA4, and Th1-related transcription factors such as T-bet in the heart (Figs. 5 and 6). As known, the immune system is closely associated with the progression of inflammation of the cardiovascular system. In regulating immune function and inflammatory response in the cardiovascular system, the balance between Th1-related cytokine expression and Th2-related cytokine expression is demonstrated to be important [56–58].

As suggested, STAT1 is associated with IFN-γ expression and plays an important role in Th1-specific cytokine expression [59]. IFN-γ can induce Th1 activation by activating STAT1, which in turn activates T-bet. The upregulated T-bet expression is closely related to the mediation of STAT1. Wei et al. showed that the STAT1-, STAT3-, STAT6-dependent pathways mediated the activation of T-bet, GATA3, and GATA4 [60], suggesting that the upregulation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 may be risk factors for the progression of cardiovascular injuries following exposure to TiO2 NPs. Furthermore, GATA3, GAT4, and STAT6 were suggested to influence Th2 cell differentiation and induce expression of IL-4 and IL-6 [61, 62]. GATA3 and GATA4 can drive differentiation of Th2 cells, whereas T-bet can promote expansion of Th1 cells [63]. Wojakowski et al. observed that GATA-4 expression in patients with acute myocardial infarction related to the increased levels of inflammatory cytokines was significantly upregulated [64]. The balance between GATAs/T-bet may be related to the fate of T cell polarization during the immune response. Szabo et al. demonstrated that T-bet can drive chromatin remodeling of the IFN-γ locus and plays a key role in Th1 cell development and regulation [65]. Increased level of STAT1, STAT3, STAT6, GATA3, GATA4, IL-4, IL-6, IFN-γ, and T-bet expression (Figs. 5 and 6) demonstrated that TiO2 NP exposure could alter the expression of Th1- and Th2-related transcription factors, suggesting that chronic exposure to TiO2 NPs impaired the balance of Th1 and Th2 at the transcriptional levels. Because the Th1/Th2 imbalance could promote the progression of allergy or infection [66], our results partly explained that TiO2 NPs may impair balance of Th1 and Th2 cytokines and alter the immune response toward the allergy-related Th2 cytokines. IL-6 is a vital procoagulant cytokine, and it contributes to enhance plasma CRP concentration, which exacerbates inflammatory and procoagulant responses [67]. Inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α, and CRP, have been suggested to induce the expression of cellular adhesion molecules, which promote adhesion of leukocytes to the vascular endothelium [68, 69]. CRP can also activate monocytes to express a glycoprotein tissue factor that plays a critical role in coagulation [70]. Importantly, endothelium-derived NOx production is decreased at the damaged vascular site. Therefore, a reduction in NOx activity exacerbates a pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic milieu. CRP may itself play an important role in decreasing NOx production and bioavailability [71]. Therefore, cardiac lesion caused by TiO2 NP exposure may be associated with alterations of cytokine expression and immunological function in myocardium and the imbalance of Th1 and Th2 cytokines.

Conclusions

TiO2 NP exposure resulted in cardiac inflammation coupling with pulmonary inflammation, which may be associated with immune dysfunction and imbalance of Th1-related cytokine expression and Th2-related cytokine expression in mouse heart. The finding exhibits new insight into the mechanisms of the TiO2 NP-induced cardiovascular damage. However, the interaction of other Th1/Th2-related cytokines associated with TiO2 NP-induced cardiovascular injury will be further investigated in future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81473007, 81273036, 30901218).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FH and LW contributed to the design of the whole study and the proof reading of the paper. XY, YZ, JH, and LS contributed to the experiments of animal treatment, histopathological examination, and assay of gene and protein expression. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, III, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC, Jr, Whitsel L, Kaufman JD. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–2378. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Robinson SD, Gonzalez M, Darnley K, MacNee W, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, Newby DE. Diesel exhaust inhalation causes vascular dysfunction and impaired endogenous fibrinolysis. Circulation. 2005;112:3930–3936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seaton A, Tran L, Aitken R, Donaldson K. Nanoparticles, human health hazard and regulation. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7(Suppl 1):S119–S129. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0252.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreyling WG, Semmler M, Erbe F, Mayer P, Takenaka S, Schulz H, Oberdörster G, Ziesenis A. Translocation of ultrafine insoluble iridium particles from lung epithelium to extrapulmonary organs is size dependent but very low. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:1513–1530. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J. Nanotoxicology. an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(7):823–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JJ, Sanderson BJS, Wang H. Cyto- and genotoxicity of ultrafine TiO2 particles in cultured human lymphoblastoid cells. Mutat Res. 2007;628:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warheit DB, Webb TR, Reed KL, Frerichs S, Sayes CM. Pulmonary toxicity study in rats with three forms of ultrafine-TiO2 particles: Differential responses related to surface properties. Toxicity. 2007;230:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li JG, Li QN, Xu GY, Li J, Cai XQ, Liu RL. Comparative study on the acute pulmonary toxicity induced by 3 and 20 nm TiO2 primary particles in mice. Environ Toxic Pharmacol. 2007;24:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang HH, Wick RL, Xing BS. Toxicity of nanoparticulate and bulk ZnO, Al2O3 and TiO2 to the nematode caenorhabditis elegans. Environ Pollut. 2009;157:1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong D, Fang T, Yu L, Sima X, Zhu W. Effects of nano-scale TiO2, ZnO and their bulk counterparts on zebrafish: acute toxicity, oxidative stress and oxidative damage. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409(8):1444–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheng L, Wang XC, Sang XZ, Ze YG, Zhao XY, Liu D, Gui SX, Sun QQ, Cheng J, Cheng Z, Hu RP, Wang L, Hong FS. Cardiac oxidative damage in mice following exposure to nanoparticlate titanium dioxide. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2013;101A:3238–3246. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu XH, Zhao XY, Ze YG, Wang L, Liu D, Hong J, Xu BQ, Lin AA, Zhang C, Zhao Y, Li BY, Hong FS. Changes of serum parameters of TiO2 nanoparticle-induced atherosclerosis in mice. J Hazard Mater. 2014;280:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu HT, Ma LL, Zhao JF, Liu J, Yan JY, Ruan J, Hong FS. Biochemical toxicity of mice caused by nano-anatase TiO2 particles. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;129:170–180. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikkelsen L, Sheykhzade M, Jensen KA, Saber AT, Jacobsen NR, Vogel U, Wallin H, Loft S, Møller P. Modest effect on plaque progression and vasodilatory function in atherosclerosis-prone mice exposed to nanosized TiO2. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han SG, Newsome B, Hennig B. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles increase inflammatory responses in vascular endothelial cells. Toxicology. 2013;306:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faddah LM, Abdel Baky NA, Mohamed AM, Al-Rasheed NM, Al-Rasheed NM. Protective effect of quercetin and/or L-arginine against nano-zinc oxide-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. J Nanopart Res. 2013;15:1520–1533. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1520-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mroz RM, Schins RP, Li H, Jimenez LA, Drost EM, Holownia A, MacNee W, Donaldson K. Nanoparticle-driven DNA damage mimics irradiation-related carcinogenesis pathways. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):241–251. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00006707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JS, Yoon TJ, Yu KN, Kim BG, Park SJ, Kim HW, Lee KH, Park SB, Lee JK, Cho MH. Toxicity and tissue distribution of magnetic nanoparticles in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2006;89:338–347. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang B, Feng WY, Wang M, Wang TC, Gu YQ, Zhu MT, Ouyang H, Shi JW, Zhang F, Zhao YL, Chai ZF, Wang HF, Wang J. Acute toxicological impact of nano and submicro-scaled zinc oxide powder on healthy adult mice. J Nanopart Res. 2008;10(2):263–276. doi: 10.1007/s11051-007-9245-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, III, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong YL, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC, Jr, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease application to clinical and public health practice a statement for healthcare professionals from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang P, Lu C, Hua N, Du Y. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles co-doped with Fe3+ and Eu3+ ions for photocatalysis. Mater Lett. 2002;57:794–801. doi: 10.1016/S0167-577X(02)00875-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu RP, Zheng L, Zhang T, Cui YL, Gao GD, Cheng Z, Chen J, Tang M, Hong FS. Molecular mechanism of hippocampal apoptosis of mice following exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J Hazard Mater. 2011;191:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma LL, Zhao JF, Wang J, Liu J, Duan YM, Liu HT, Li N, Yan YJ, Ruan J, Wang H, Hong FS. The acute liver injury in mice caused by nano-anatase TiO2. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2009;4:1275–1285. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9393-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ze YG, Zheng L, Zhao XY, Gui SX, Sang XZ, Su JJ, Guan N, Zhu LY, Sheng L, Hu RP, Cheng J, Cheng Z, Sun QQ, Wang L, Hong FS. Molecular mechanism of titanium dioxide nanoparticles-induced oxidative injury in the brain of mice. Chemosphere. 2013;92:1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NIOSH . Current intelligence bulletin 63. Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2011. Occupational exposure to titanium dioxide. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morimoto Y, Kobayashi N, Shinohara N, Myojo T, Tanaka I, Nakanishi J. Hazard assessments of manufactured nanomaterials. J Occup Health. 2010;52:325–324. doi: 10.1539/joh.R10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Cogliano V. Carcinogenicity of carbon black, titanium dioxide, and talc. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:295–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70651-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AshaRani PV, Mun GLK, Hande MP, Valiyaveettil S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano. 2009;3:279–290. doi: 10.1021/nn800596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55(4):611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schefe JH, Lehmann KE, Buschmann IR, Unger T, Funke-Kaiser H. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR data analysis: current concepts and the novel “gene expression’s CT difference” formula. J Mol Med. 2006;84:901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B, Ze YG, Sun QQ, Zhang T, Sang XZ, Cui YL, Wang XC, Gui SX, Tan DL, Zhu M, Zhao XY, Sheng L, Wang L, Hong FS, Tang M. Molecular mechanisms of nanosized titanium dioxide–induced pulmonary injury in mice. Plos One. 2013;8(2):e55563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Shannahan JH, Kodavanti UP, Brown JM. Manufactured and airborne nanoparticle cardiopulmonary interactions: a review of mechanisms and the possible contribution of mast cells. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:320–339. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.668229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seaton A, Soutar A, Crawford V, Elton R, McNerlan S, Cherrie J, Watt M, Agius R, Stout R. Particulate air pollution and the blood. Thorax. 1999;54:1027–1032. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.11.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alonso-Martinez JL, Llorente-Diez B, Echegaray-Agara M, Olaz-Preciado F, Urbieta-Echezarreta M, Gonzalez-Arencibia C. C-reactive protein as a predictor of improvement and readmission in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(3):331–336. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anand IS, Latini R, Florea VG, Kuskowski MA, Rector T, Masson S, Signorini S, Mocarelli P, Hester A, Glazer R, Cohn JN. C-reactive protein in heart failure: prognostic value and the effect of valsartan. Circulation. 2005;112(10):1428–1434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teerlink JR. Endothelins: pathophysiology and treatment implications in chronic heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2005;2(4):191–197. doi: 10.1007/BF02696649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Killian JM, Roger VL. Tumor necrosis factor-α and mortality in heart failure: a community study. Circulation. 2008;118(6):625–631. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huo Y, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Ley K. Role of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and fibronectin connecting segment-1 in monocyte rolling and adhesion on early atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2000;87:153–159. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsakadze NL, Sithu SD, Sen U, English WR, Murphy G, D’Souza SE. Tumor Necrosis Factor-a-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM-17) mediates the ectodomain cleavage of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3157–3164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonetti PO, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Endothelial dysfunction: a marker for atherosclerotic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:168–175. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000051384.43104.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang JL, Park W, Pack IS, Lee HS, Kim MJ, Lim CM, Koh Y. Inhaled nitric oxide attenuates acute lung injury via inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and inflammation. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:795–801. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00202.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan ZQ, Yokota T, Zhang W, Hansson GK. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibits platelet adhesion and restores blood flow in the injured artery. Circ Res. 1996;79:38–44. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.79.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts W, Riba R, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Farndale RW, Naseem KM. Nitric oxide specifically inhibits integrin-mediated platelet adhesion and spreading on collagen. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:2175–2185. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amiri F, Virdis A, Neves MF, Iglarz M, Seidah NG, Touyz RM, Reudelhuber TL, Schiffrin EL. Endothelium-restricted overexpression of human endothelin-1 causes vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110:2233–2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144462.08345.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bujak M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of TGF-beta signaling in myocardial infarction and cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Transforming growth factor-beta: recent progress and new challenges. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1017–1021. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malek S, Kaplan E, Wang JF. Successful implantation of intravenously administered stem cells correlates with severity of inflammation in murine myocarditis. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:268–275. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lang C, Sauter M, Szalay G, Racchi G, Grassi G, Rainaldi G, Mercatanti A, Lang F, Kandolf R, Klingel K. Connective tissue growth factor: a crucial cytokine-mediating cardiac fibrosis in ongoing enterovirus myocarditis. J Mol Med. 2008;86:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kania G, Blyszczuk P, Stein S, Valaperti A, Germano D, Dirnhofer S, Hunziker L, Matter CM, Eriksson U. Heart-Infiltrating Prominin-1+/CD133+ Progenitor cells represent the cellular source of transforming growth factor β–mediated cardiac fibrosis in experimental autoimmune myocarditis. Circ Res. 2009;105:462–470. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li RK, Li G, Mickle DA, Weisel RD, Merante F, Luss H, Rao V, Christakis GT, Williams WG. Overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta1 and insulin-like growth factor-I in patients with idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;96:874–881. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.3.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patrov VV, Fagard RH, Lijnen PJ. Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth factor-h1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Hypertension. 2002;39:258–263. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palaniyandi SS, Watanabe K, Ma M, Tachikawa H, Kodama M, Aizawa Y. Inhibition of mast cells by interleukin-10 gene transfer contributes to protection against acute myocarditis in rats. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3508–3515. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nimata M, Okabe TA, Hattori M, Yuan Z, Shioji K, Kishimoto C. MCI-186 (edaravone), a novel free radical scavenger, protects against acute autoimmune myocarditis in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2514–H2518. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00661.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paolocci N, Sironi M, Bettini M, Bartoli G, Michalak S, Bandi C, Magni F, Bruschi F. Immunopathological mechanisms underlying the time-course of Trichinella spiralis cardiomyopathy in rats. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s004280050164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding L, Hanawa H, Ota Y, Hasegawa G, Hao K, Asami F, Watanabe R, Yoshida T, Toba K, Yoshida K, Ogura M, Kodama M, Aizawa Y. Lipocalin-2/neutrophil gelatinase-B associated lipocalin is strongly induced in hearts of rats with autoimmune myocarditis and in human myocarditis. Circ J. 2010;74:523–530. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Polidori A, Arhami M, Gillen DL, Kleinman MT, Vaziri ND, Longhurst J, Zaldivar F, Sioutas C. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation, antioxidant activity, and platelet activation are associated with primary combustion aerosols in subjects with coronary artery disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:898–906. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao JZ, Xie YQ, Qiana XL, Jiang RF, Song WM. Acute effects of fine particles on cardiovascular system: differences between the spontaneously hypertensive rats and wistar kyoto rats. Toxicol Lett. 2010;193:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao JZ, Xie YQ, Qian CY, Li L, Jiang RF, Kan HD, Chen RZ, Song WM. Imbalance of Th1 and Th2 cells in cardiac injury induced by ambient fine particles. Toxicol Lett. 2012;208:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, Glimcher LH. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:713–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei J, Duramad O, Perng OA, Reiner SL, Liu YJ, Qin FX. Antagonistic nature of T helper 1/2 developmental programs in opposing peripheral induction of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18169–18174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703642104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li B, Tournier C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. Regulation of IL-4 expression by the transcription factor JunB during T helper cell differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18:420–432. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy KM, Reiner SL. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:933–944. doi: 10.1038/nri954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rengarajan J, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH. Transcriptional regulation of Th1/Th2 polarization. Immunol Today. 2000;21:479–483. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wojakowski W, Tendera M, Michałowska A, Majka M, Kucia M, Maślankiewicz K, Wyderka R, Ochala A, Ratajczak MZ. The mobilization of CD34/CXCR4+, CD34/CD117+, c-met + stem cells and mononuclear cells expressing early cardiac, muscle and endothelial markers into peripheral blood in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110:3213–3220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147609.39780.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seymour BW, Pinkerton KE, Friebertshauser KE, Coffman RL, Gershwin LJ. Second-hand smoke is an adjuvant for T helper-2 responses in a murine model of allergy. J Immunol. 1997;159:6169–6175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yeh ETH, Anderson HV, Pasceri V, Willerson JT. C-reactive protein: linking inflammation to cardiovascular complications. Circulation. 2001;104:974–975. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.104.9.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Willerson JT. Systemic and local inflammation in patients with unstable atherosclerotic plaques. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2002;44:469–478. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2002.123782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Roitman-Johnson B, Stampfer MJ, Allen J. Plasma concentration of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and risks of future myocardial infarction in apparently healthy men. Lancet. 1998;351:88–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakagomi A, Feedman SB, Geczy CL. Interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide potentiate monocyte tissue factor induction by C-reactive protein. Relationship with age, sex, and hormone replacement treatment. Circulation. 2000;101:1785–1791. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.15.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verma S, Wang CH, Li SH, Dumont AS, Fedak PW, Badiwala MV, Dhillon B, Weisel RD, Li RK, Mickle DA, Stewart DJ. A self-fulfilling prophecy. C-reactive protein attenuates nitric oxide production and inhibits angiogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000029802.88087.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]