Introduction

Sterile corneal ulcers and perforations can occur as a result of eye injury, Mooren's ulcer etc as an isolated ocular problem or they may be associated with various collagen vascular or other autoimmune diseases. Recurrent corneal erosions, exposure keratitis, neurotrophic keratitis, keratomalacia that affect the integrity of the ocular surface epithelium may also sometimes result in the development of sterile corneal ulcers.1Sterile corneal ulceration is a serious complication in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca.1–4 The common etiologies of dry eyes leading to corneal perforation include Sjogren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, ocular pemphigoid, atopy and local irradiation.2–4 We report an uncommon case of sterile corneal perforation in severe dry eye without any underlying systemic cause.

Case report

A 20-year-old male patient, presented to us for an ophthalmology consultation as he had developed redness, foreign body sensation, mucoid discharge, burning in eyes of 2 months duration. Ocular examination on presentation revealed a normal vision of 6/6 in both his eyes. However his eyelashes were matted with a mucoid discharge conjunctival congestion was present and the cornea was dry and lusterless in both his eyes. Schirmer's test reading was 02 mm bilaterally, suggesting severe dry eyes; however the corneal sensations were normal. Rest of the ocular examination was normal. Hematological tests and investigations for collagen vascular diseases were all negative. A provisional diagnosis of dry eyes was made. He was prescribed preservative free tear substitutes at 2 h intervals as well as a lubricating eye ointment at bedtime. The patient was advised to come for weekly review, however due to some family commitments he could not come and reported only after 3 months with severe pain redness and diminution of vision in his left eye. Ocular examination of the right eye was as earlier but left eye revealed his vision reduced to just finger counting close to face. Slit lamp examination showed a 02 mm central corneal perforation with a shallow anterior chamber and iris incarceration in the wound. Cultures from the conjunctiva and cornea were all sterile. The anterior chamber was reformed with viscoelastic, the iris was pushed back, cyanoacrylate fibrin glue was used to seal the perforation, a bandage contact lens was placed and the eye was patched. On the next day, the perforation had sealed, topical tear substitutes and moxifloxacin eye drops were started. Distant visual acuity in right eye was 6/6 and 6/18 in the left eye. He was then treated for severe dry eye with cyclosporine and tear substitutes. However, his symptoms in the form of redness and foreign body sensation increased, for which he underwent a collagen lacrimal plug implantation in left lower and upper lids. After 2 weeks, the patient again developed 2.5 mm paracentral perforation with iris prolapse in the same left eye. Cultures from the conjunctiva and cornea were again sterile. The perforation was sealed with fibrin glue and the amniotic membrane was secured over it by the sutures. Corneal healing was initially slow, however over a period of 10 days corneal epithelization occurred with the formation of a pseudocornea (Figs. 1–3).

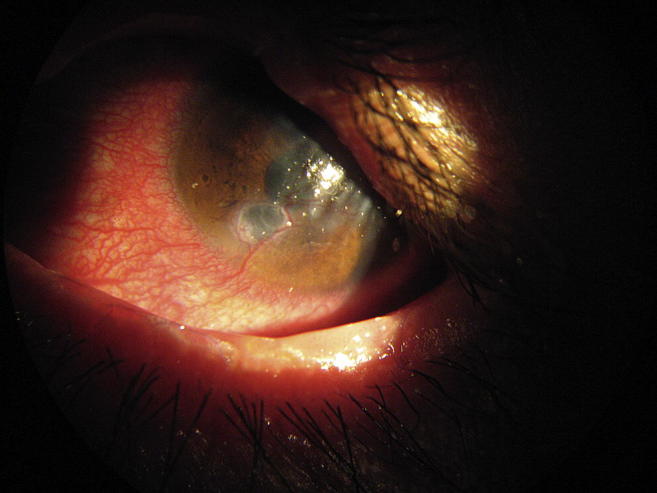

Fig. 1.

Photo of patient with corneal perforations in left eye.

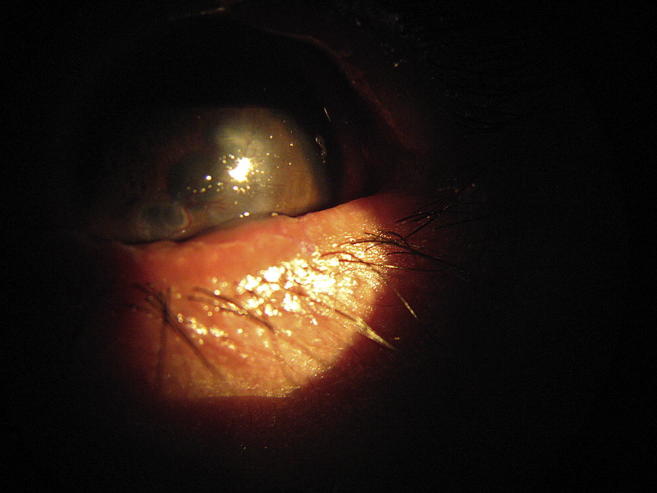

Fig. 2.

Left eye showing healed corneal perforations.

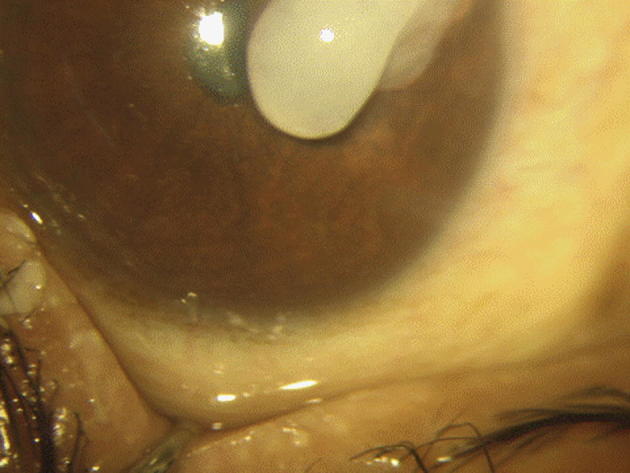

Fig. 3.

Fresh and healed corneal perforations in left eye.

A diagnosis of severe dry eyes with sterile perforated corneal ulcer left eye with pseudocornea left eye was made. Presently, right eye visual acuity is 6/6, eye is quiet, cornea is lusterless, anterior chamber is formed and the eye is dry. Visual acuity in left eye is reduced to hand movements close to face (HMCF), eye is quiet, pseudocornea with adherent leucoma is present. He is on topical tear substitutes (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4.

Use of glue for corneal perforation.

Fig. 5.

Use of amniotic membrane for corneal perforation.

Discussion

Dry eye is a very common multifactorial disease of the tears and the ocular surface affecting a significant percentage (approximately 10–30%) of the population, especially those older than 40 years.5 It causes ocular discomfort, visual disturbance and tear film instability leading sometimes to permanent irreversible dimness of vision.2,4,5 Dry eye may be complicated by sterile or infectious central or paracentral, oval or circular, less than 3 mm in diameter corneal ulceration, particularly in patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Occasionally, corneal perforation may occur in these cases. In rare cases, sterile or infectious corneal ulceration in dry eye syndrome can cause blindness. Other complications include punctuate epithelial defects, corneal neovascularization, and corneal scarring.2,4,5

Sterile ocular perforations, which are uncommon without any underlying systemic cause in a case of dry eyes, occurred in our case. Despite prompt intervention, pseudocornea and adherent leucoma formation could not be prevented. However, the integrity of the globe could be maintained. The use of fibrin glue for sealing corneal perforations has also been documented earlier.6 The possibility of the risks for transmission with prion and parvovirus B19 (HPV B19) diseases are minimal.7

In this case corneal perforations occurred despite regular use of tear substitutes. The left eye perforations could be closed with the timely use of fibrin glue with amniotic membrane.8 Amniotic membrane supports epithelization due to presence of growth factors. In conclusion one should not take cases of dry eyes lightly but specifically look for sudden diminution of vision, photophobia, redness and discharge in eyes on each visit to detect corneal ulcers and perforations in time so as to prevent its sequelae.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Hemady R., Chu W., Foster C.S. Management of noninfectious corneal ulcers. Surv Ophthalmol. 1987 Sep–Oct;32(2):94–110. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(87)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petroutsos G., Paschides C.A., Kitsos G., Skopouli F.N., Psilas K. Sterile corneal ulcers in dry eye. Incidence and factors of occurrence. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1992;15(2):103–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottsch J.D., Akpek E.K. Topical cyclosporine stimulates neovascularization in resolving sterile rheumatoid central corneal ulcers. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:81–87. discussion 87–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemady R., Chu W., Foster C.S. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and corneal ulcers. Cornea. 1990 Apr;9(2):170–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) Committee Report of the dry eye workshop (DEWS) Ocul Surf. April 2007;5(2):65–204. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panda A., Kumar S., Kumar A., Bansal R., Bhartiya S. Fibrin glue in ophthalmology. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:371–379. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.55079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hino M., Ishiko O., Honda K.I. Transmission of symptomatic parvovirus B19 infection by fibrin sealant used during surgery. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:194–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hick S., Demers P.E., Brunette I., La C., Mabon M., Duchesne B. Amniotic membrane transplantation and fibrin glue in the management of corneal ulcers and perforations: a review of 33 cases. Cornea. 2005;24:369–377. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000151547.08113.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]