Abstract

Candida albicans is normally a commensal fungus of the human mucosae and skin, but it causes life-threatening systemic infections in hospital settings in the face of predisposing conditions, such as indwelling catheters, abdominal surgery, or antibiotic use. Immunity to C. albicans involves various immune parameters, but the cytokine interleukin-17A (IL-17A) (also known as IL-17) has emerged as a centrally important mediator of immune defense against both mucosal and systemic candidiasis. Conversely, IL-17A has been suggested to enhance the virulence of C. albicans, indicating that it may exert detrimental effects on pathogenesis. In this study, we hypothesized that a C. albicans strain expressing IL-17A would exhibit reduced virulence in vivo. To that end, we created a Candida-optimized expression cassette encoding murine IL-17A, which was transformed into the DAY286 strain of C. albicans. Candida-derived IL-17A was indistinguishable from murine IL-17A in terms of biological activity and detection in standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Expression of IL-17A did not negatively impact the growth of these strains in vitro. Moreover, the IL-17A-expressing C. albicans strains showed significantly reduced pathogenicity in a systemic model of Candida infection, mainly evident during the early stages of disease. Collectively, these findings suggest that IL-17A mitigates the virulence of C. albicans.

INTRODUCTION

Candida albicans is a commensal fungus of human skin and mucosal surfaces. Although normally nonpathogenic, C. albicans can cause disease in settings of immunodeficiency, abdominal surgery or otherwise disrupted barriers, antibiotic use, or other conditions (1, 2). By far the most serious form of candidiasis is a systemic infection characterized by fungal invasion into target organs, particularly the liver, kidney, and brain (3). Disseminated candidiasis is the 4th most common cause of hospital-acquired infections and has a high mortality rate (averaging 40%) (4).

In recent years, accumulating data have implicated the cytokine interleukin-17A (IL-17A) (also known as IL-17) in immunity to Candida and other fungi (5, 6). IL-17A- and IL-17 receptor-deficient mice are highly susceptible to candidemia (7–9). Similarly, humans with defects in the IL-17 pathway are especially sensitive to Candida infections; the defects arise from mutations in genes controlling IL-17 signaling (ACT1, IL17RA, IL17RC, and IL17F) or genes that drive Th17 cell differentiation (DECTIN1, CARD9, STAT3, STAT1, IL12B, and IL12RB) or arise in individuals with naturally occurring anti-IL-17 antibodies (occurring in certain thymomas and AIRE deficiency, also known as autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 [APS-1] or autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy [APECED]) (10, 11).

Although Candida infections can be treated pharmacologically, currently available antifungal medications are limited by significant drug-drug interactions, the emergence of drug resistance, and toxicity (12, 13). To date, there are no vaccines available for any fungal species, although an experimental vaccine to treat vaginal candidiasis is in development (14, 15). Experimental vaccines for Candida and other pathogenic fungi have been shown to require intact Th17 responses (16, 17). In contrast, it has been suggested that IL-17A may act directly on C. albicans to increase its virulence in a gastric model of candidiasis (18). Therefore, understanding the correlates of immunity and particularly the impact of IL-17 activity in the context of Candida infections is important in designing new drugs or preventive strategies to treat candidiasis. Accordingly, our goal in this study was to determine whether ectopic expression of IL-17A by Candida was protective or pathogenic in the context of disease. To that end, we created a yeast strain expressing murine IL-17A and demonstrated that there is an improved host response to this strain during a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, Candida transformation, and culture.

An expression cassette was constructed containing the first 1,000 bp of the Candida TDH3 promoter, the secreted Candida SAP5 signal sequence (SS), and the open reading frame (ORF) of murine Il17a. The TDH3 promoter (driving Candida albicans glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]) was chosen due to its high constitutive expression in yeast. The sequence of mouse Il17a was optimized for expression in C. albicans by GeneArt (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with its native SS removed. The murine Il17a SS was identified by comparison to the known human IL17A SS (19) and prediction software from SignalP 4.0 server (20). To assemble the cassette, fragments were recombined into histidine-negative Saccharomyces cerevisiae by homologous recombination (gap repair) in the plasmid pSG1 (histidine positive) and grown on selective media. The resulting plasmid was purified from S. cerevisiae, transformed into Escherichia coli, and verified by sequencing. The linearized cassette was recombined into the C. albicans strain DAY286 genome by lithium acetate transformation. Positive colonies were identified by growth on selective media and colony PCR. The Candida IL-17A primers were 5′-GCTATGACCATGATTACGCC and 3′-TATAATGTTTATCTAACAAAGATGTTGTGT. Strains were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) at 30°C or stored at −80°C in 15% glycerol.

Filamentation assay.

Strains were cultured overnight at 30°C and diluted into fresh RPMI 1640 at 37°C at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 for 90 min. Samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), stained with Calcofluor (200 μg/ml), and visualized with a Zeiss Axio Observer Z.1 fluorescence microscope and a 20× objective with 1.6 optivar. Seven Z-stack images were assembled per image. To obtain a quantitative assessment of filamentation, filament length was measured in a blind manner on enlarged images and presented as a filament index with arbitrary units.

Cell culture, cytokine stimulations and histology.

ST2 stromal cells were cultured with Eagle minimum essential medium alpha modification (α-MEM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine, and antibiotics (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Recombinant IL-17 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and used at 10 ng/ml and 1 ng/ml, respectively. The cells were stimulated with supernatant from IL-17A-secreting Candida or the parent DAY286 strain diluted 1:10 in α-MEM with 10% FBS with or without TNF-α for 6 h at 37°C. Additional samples were incubated with anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (10 μg/ml) or isotype controls (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) starting 1 h prior to cytokine stimulation and continuing throughout the incubation period. Supernatants were analyzed for IL-6 and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 (CXCL5) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). IL-6 ELISA kits were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and CXCL5 ELISA kits were from R&D Systems. For histology, kidney samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) or periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) by the University at Buffalo Histology Core (Buffalo, NY). The slides were analyzed in a blind manner, and images were captured on an EVOS FL microscope system (Life Technologies). RNA from kidney was prepared with Qiagen RNeasy kits with an on-column DNase digestion step, and cDNA was prepared with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). PCR primers for detection of Candida in kidney tissue were as follows: TDH3 (5′-ATCCCACAAGGACTGGAGA and 3′-ATCCCACAAGGACTGGAGA), Ca-IL-17A (5′-TTTGCTTTATTAATTGATGCT and 3′-ATGAAACTTTAGCACCCAATG. Samples were visualized on a 2.5% agarose gel and imaged on a Protein Simple instrument (Wallingford, CT).

Mice and infections.

C57BL/6 female mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were used at 6 to 10 weeks of age. IL-17RA−/− (IL-17RA stands for interleukin 17A receptor) mice (C57BL/6 background) were provided by Amgen and bred in-house (21). Mice were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle and specific-pathogen-free (SPF) conditions and provided with autoclaved food and water ad libitum. Mice were injected in the tail vein with the indicated Candida strains at 2 × 105 yeast cells or sterile saline vehicle control as described previously (22). For injections, mice were briefly held in a commercial restraining apparatus (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA). Mice were monitored visually and weighed at least once daily. Mice were humanely sacrificed by CO2 inhalation at the termination of each experiment or if animals exhibited >20% weight loss or showed signs of pain or distress as delineated by the approved animal protocol. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all animal protocols used in this study (Animal welfare assurance number A3187-01). All efforts were made to minimize suffering in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (23). Tissues were harvested in a Miltenyi GentleMACS dissociator and plated in serial dilutions on YPD-Amp (YPD with ampicillin) agar plates.

RESULTS

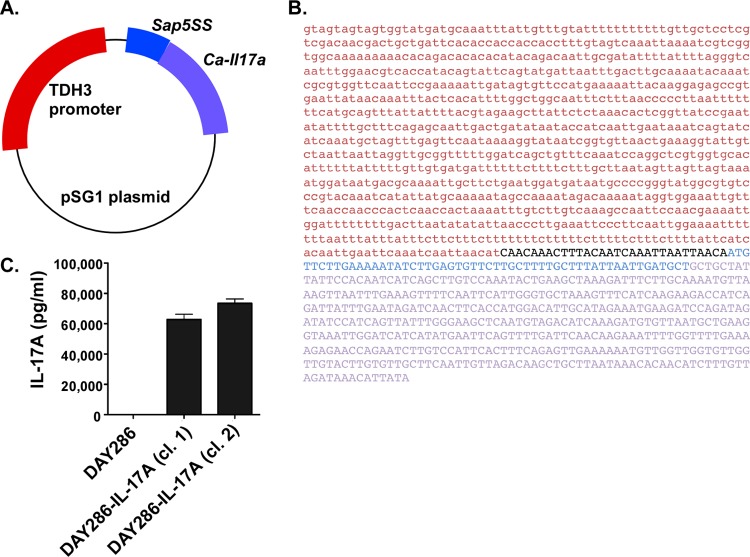

To create a strain of C. albicans that secretes a form of IL-17A that can be recognized in vivo, we synthesized a recombinant cassette composed of a constitutive Candida albicans TDH3 promoter (which regulates the C. albicans GAPDH gene) driving the murine Il17a gene (Fig. 1A). The native signal sequence (SS) of Il17a was replaced by the SS of the fungal secreted aspartyl proteinase 5 (SAP5). The IL-17A sequence was optimized for expression in C. albicans (Fig. 1B). These cassettes were recombined into the pSG1 plasmid with a histidine selective marker (24). The plasmid was transformed into C. albicans strain DAY286 (25), positive colonies were identified by growth on selective media, and colony PCR was performed to verify insertion of the Il17a gene (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Engineering an IL-17A-secreting strain of Candida albicans. (A) Diagram of the construct used to express IL-17A in C. albicans. The constitutive TDH3 promoter encoding GAPDH of C. albicans was used to drive expression. The Sap5 signal sequence (Sap5SS) is derived from the yeast secreted aspartyl proteinase gene and is fused to a codon-optimized open reading frame encoding murine IL-17A without its native signal sequence. (B) Sequence of the TDH3 promoter (red) and the SAP5SS-IL-17A fusion gene (SAP5SS sequence shown in blue, and IL-17A sequence shown in purple) are shown. The intervening pSG1-derived sequence is shown in black. (C) Expression of murine IL-17A was detected by ELISA in conditioned media from two C. albicans clones (clones 1 and 2) compared to the parent C. albicans DAY286 strain. Two clones of strain DAY286 expressing IL-17A (DAY286-IL-17A) were tested. The experiment was repeated three times.

To determine whether the recombinant C. albicans strains expressed IL-17A protein, two independently derived strains of strain DAY286 expressing IL-17A (DAY286-IL-17A) were cultured for 16 h at 30°C, and conditioned supernatants were serially diluted and analyzed by ELISAs. As shown, both strains exhibited substantial production of IL-17A (with a mean production of 74,829 pg/ml), whereas no IL-17A or cross-reactive contaminants were detected in the supernatant from the parent DAY286 strain (Fig. 1C). Therefore, C. albicans can be engineered to secrete mammalian IL-17A.

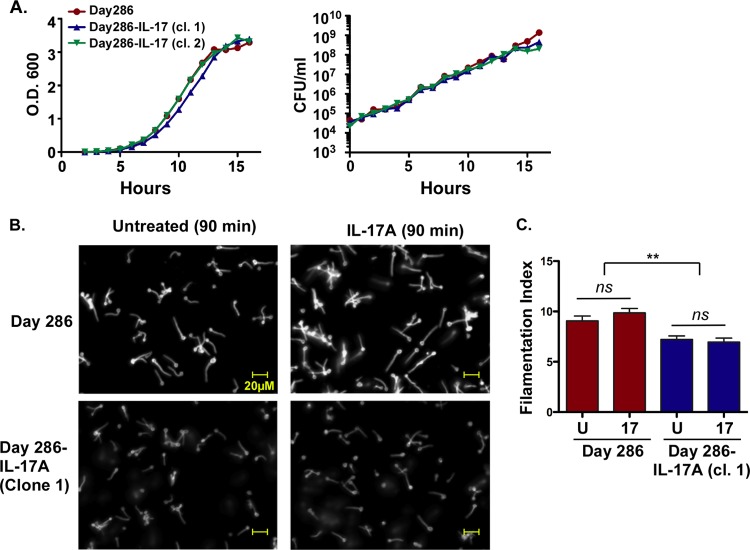

Although IL-17A has been reported to negatively impact the virulence of C. albicans by direct action on the fungus (18), the growth curve of IL-17A-expressing C. albicans DAY286 was indistinguishable from the parent strain, indicating that ectopic expression of IL-17A is not detrimental to C. albicans growth in vitro (Fig. 2A). Moreover, expression of IL-17A in the positive clones was stable over at least 2 months of culture (data not shown). In characterizing this strain, we noticed that one of the IL-17A-producing strains exhibited enhanced sensitivity to caspofungin (C. A. Woolford, unpublished data), perhaps suggesting alterations in the cell wall. Accordingly, we measured the filamentation capacity of the parent and IL-17A-expressing strains. Candida strains were cultured in RPMI 1640 for 90 min, stained with Calcofluor, and visualized as a Z-stack of seven compiled images (Fig. 2B). Filamentation length was measured in a blind manner on representative enlarged images. Unexpectedly, there was a difference in the average germ tube length between parental and IL-17A-expressing strains, with the DAY286-IL-17A germ tubes ∼25% shorter than the parent strain germ tubes (Fig. 2C). To determine whether IL-17 signaling acting directly on the fungus caused these differences, yeast strains were cultured in 100 ng/ml recombinant murine IL-17A during filamentation. However, there was no difference in either the parent or the IL-17A-expressing strain upon addition of IL-17, indicating that exogenous exposure to this cytokine does not alter the filamentation capacity of the fungus (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG 2.

Characterization of IL-17A-secreting C. albicans. (A) The indicated C. albicans strains were cultured in YPD broth over 16 h, the optical density at 600 nm (O.D.600) of samples of the strains were determined (left), and the strains were plated for colony enumeration (right) at regular intervals. The experiment was performed once. (B and C) The indicated strains were cultured in RPMI 1640 for 90 min to induce filamentation with recombinant mouse IL-17A (100 ng/ml) or without recombinant mouse IL-17A (untreated), and germ tube length was assessed in enlarged images. All the images in panel B were taken at the same magnification. Experiments were performed twice. In panel C, the treatments are recombinant mouse IL-17A (17) or untreated (U). Values that are significantly different are indicated by a bar and two asterisks (P < 0.01). Values that are not significantly different (ns) are also indicated. Significance was assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Tukey's test.

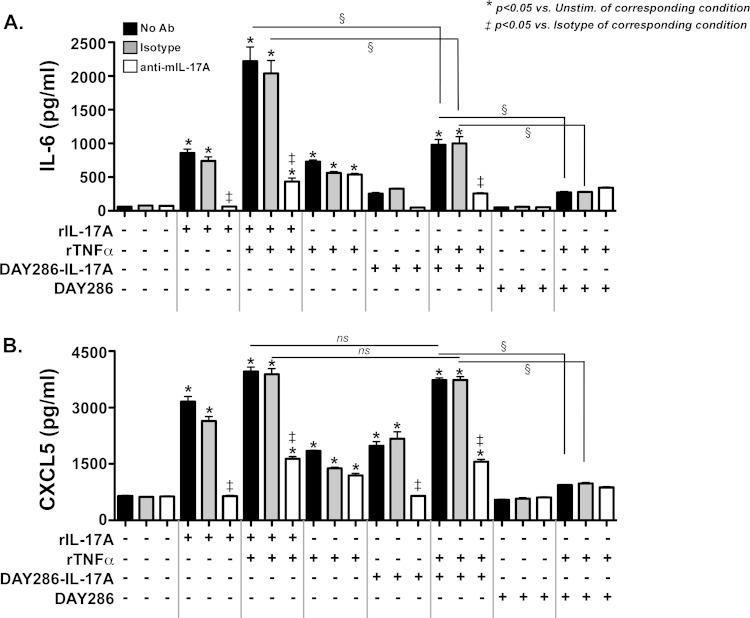

To determine whether the IL-17A produced by these Candida strains was biologically active, we used a mammalian cell culture assay to detect signaling by yeast-derived IL-17A. In mammals, IL-17A is produced dominantly by lymphocytes, but its main biological activity is on nonhematopoietic cells, particularly fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Even in these cell types, IL-17A-mediated signaling by itself is fairly modest. However, IL-17A exhibits potent signaling synergy in cooperation with TNF-α to induce expression of downstream cytokines such as IL-6 (26, 27). Therefore, we evaluated the activity of Candida-derived IL-17 in the presence or absence of suboptimal concentrations of TNF-α using a mouse bone marrow stromal cell line, ST2, which responds to IL-17 by expressing characteristic gene products such as IL-6 and the chemokine CXCL5 (28). First, we confirmed that recombinant murine IL-17 (rIL-17A) (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (1 ng/ml) induced IL-6 and CXCL5 in ST2 cells. As expected, activation of these genes was blocked by a neutralizing antibody (Ab) against IL-17A (Fig. 3A and B). We also verified that there was no inductive effect of Candida conditioned medium from the parent DAY286 strain on ST2 cells. However, conditioned medium from DAY286-IL-17A cells (diluted 1:10 to a concentration of ∼6 to 8 ng/ml of IL-17A) induced marked secretion of both IL-6 (Fig. 3A) and CXCL5 (Fig. 3B) into the ST2 cell culture supernatant. There was no detectable difference in production of CXCL5 in response to rIL-17A compared to Candida-derived IL-17A under these conditions, although IL-6 production was reduced ∼2-fold with the Candida-derived IL-17A. We do not know the basis for these differences, though they were reproducible (A. R. Huppler, unpublished observations). Importantly, neutralizing Abs against IL-17A, but not isotype control Abs, blocked the activity of the DAY286-IL-17A culture supernatants, demonstrating specific activity of the Candida-derived IL-17A. Thus, the IL-17A produced by C. albicans was functionally comparable to mouse IL-17A.

FIG 3.

IL-17A produced by Candida is biologically active. Mouse ST2 cells were treated (+) for 6 h with recombinant IL-17A (rIL-17A) (10 ng/ml), recombinant TNF-α (rTNFα) (1 ng/ml), or a 1:10 dilution of conditioned media from DAY286 or DAY286-IL-17A (clone 2) (6 to 8 ng/ml concentration) for 6 h. The indicated samples were also treated with 10 μg/ml isotype control Ab or a neutralizing anti-murine IL-17A (anti-mIL-17A) Ab (white bars). (A and B) Supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IL-6 (A) or CXCL5 (B). Experiments were performed three times. Statistical significance is indicated by bars and symbols as follows: *, P < 0.05 compared to the value for the unstimulated sample from the corresponding condition; ‡, P < 0.05 compared to the value for the isotype-treated sample from the corresponding condition; §, P < 0.05 for the values for the indicated conditions; ns, not significant.

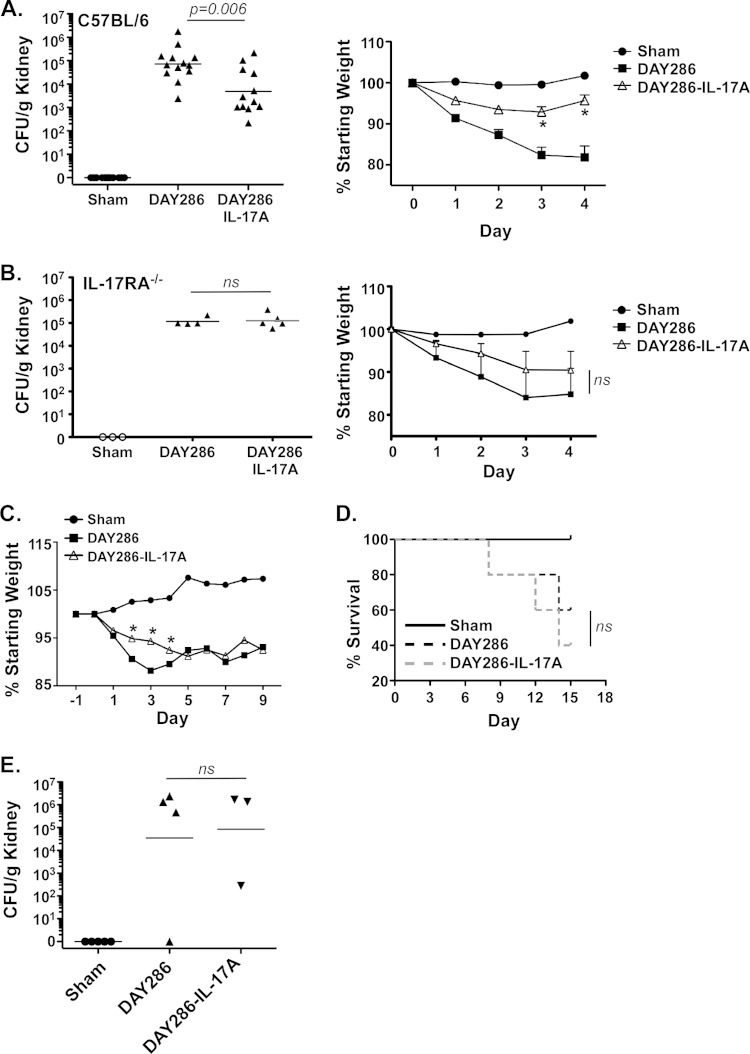

Because immunity to systemic candidiasis requires intact IL-17A signaling (7, 8), we hypothesized that IL-17A-secreting Candida strains would be less pathogenic than the parental wild-type (WT) strain. To test this hypothesis, WT C57BL/6 mice (12 or 13 mice in each group) were infected intravenously with saline (mock infected [Sham]) or with 2 × 105 CFU of strain DAY286 or DAY286-IL-17A, a dose that is commonly used in this model. Expression of Candida IL-17A in infected kidney was verified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and sequencing (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material; also data not shown). After 4 days, the mice were sacrificed, and kidney fungal burdens were assessed by plating serial dilutions of tissue homogenate on YPD agar followed by colony enumeration in triplicate. As expected, there was no C. albicans detected in the mock-infected kidneys. The geometric mean of the kidney fungal load in the DAY286-infected mice was 72,202 CFU/g, whereas in the DAY286-IL-17A-infected mice, the mean load was 4,895 CFU/g, representing an ∼15-fold reduction in the fungal burden (Fig. 4A). These differences were reproducible and statistically significant (P = 0.006). Consistent with a reduced fungal burden, there was substantially more weight loss in the DAY286-infected group than in the DAY286-IL-17A-infected group (Fig. 4A). Note that, although there is a difference in histidine biosynthesis between these strains, it has been shown that the his1 mutation does not impair pathogenicity in this model (29).

FIG 4.

IL-17A-secreting Candida albicans exhibits reduced pathogenicity in vivo early during infection. (A) (Left) WT mice (n = 12) were injected via tail vein with saline (Sham) or with 2 × 105 CFU of the indicated C. albicans strains. After 4 days, the mice were sacrificed, and kidney burden (CFU/g of kidney) was assessed by plating. Each symbol represents the value for an individual mouse, and the short line represents the geometric mean value for the group of mice. The values for the DAY286-infected group and the DAY286-IL-17A-infected group are significantly different by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Mann-Whitney correction. (Right) Weight loss at the indicated dates was assessed. The values for the DAY286-infected group that are significantly different from the values for the DAY286-IL-17A-infected group by ANOVA and Student's t test are indicated by an asterisk. (B) (Left) IL-17RA−/− mice (n = 3 or 4) were injected via tail vein with saline (Sham) or with 2 × 105 CFU of the indicated C. albicans strains. After 4 days, mice were sacrificed, and kidney burden (CFU/g) was assessed by plating. (Right) Weight loss at the indicated dates was assessed. Values that are not significant (ns) are indicated. (C) WT mice (n = 5) were injected as described above for panel A, and weight loss was measured daily. The values for the DAY286-infected group that are significantly different from the values for DAY286-IL-17A-infected group by ANOVA and Student's t test are indicated by an asterisk. (D) Survival to endpoint (20% weight loss) of the indicated cohorts. (E) Fungal load at day 15 for the remaining surviving mice (n = 3 or 4). ns, not significant. Experiments were performed one to three times.

Histological analysis of infected kidneys was consistent with the fungal load profiles. Specifically, in kidneys taken from DAY286-infected mice, H&E staining revealed distinct patches of inflammatory infiltrates in the tubular space, composed mainly of neutrophils and monocytes. The glomeruli surrounded by inflammatory cells appeared inflamed, with prominent signs of tubular atrophy. These areas corresponded to regions of dense C. albicans invasive hyphae, as visualized by PAS staining. In contrast, in DAY286-IL-17A-infected tissue, there were no obvious patches of infiltrating cells and markedly less invasive C. albicans (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). There was no evidence of tubular atrophy or inflamed glomeruli in these mice. Therefore, ectopic expression of IL-17A by C. albicans did not cause obvious renal inflammation and was associated with reduced inflammatory infiltrates and a reduction in hyphal tissue invasion. In support of this observation, we have found that overexpression of murine IL-17A in an adenoviral vector system also demonstrated no obvious inflammatory changes in the kidney (P. S. Biswas, unpublished observations).

In order to verify that the reduced fungal loads observed upon infection with the DAY286-IL-17A strain were in fact mediated by host responses rather than an intrinsic effect of the yeast (such as the reduced filamentation seen in Fig. 2), IL-17RA−/− mice were infected with both the parent and IL-17-expressing strains. As shown, there was no difference in the fungal load or weight loss upon infection with either strain (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that ectopic expression of IL-17A by C. albicans significantly reduces fungal loads during disseminated candidiasis in a manner that is dependent on host responses to IL-17 signaling.

To determine whether the effect of IL-17A was long-lasting, we infected mice and tracked weight loss and survival over a 15-day time course. Again, during the first 4 days of infection, the mice infected with strain DAY286-IL-17A showed less pronounced weight loss than mice infected with the parental DAY286 strain (Fig. 4C). However, starting at day 5 and continuing for the remainder of the experiment, there was no difference in weight loss between mice infected with either strain. There was also no difference in survival to disease endpoint (Fig. 4D) or fungal burden (Fig. 4E) in the few surviving animals (n = 3 or 4) at day 15. Therefore, the main activity of IL-17A appears to be in the early time points postinfection, with other factors coming into play at later stages of disease.

DISCUSSION

It is now well established that the IL-17/Th17 pathway is an essential component of the immune response to pathogenic Candida albicans infections, not only in mouse models of disease but also in humans (10). However, this subject remains controversial, as IL-17A has been reported to be pathogenic in gastrointestinal Candida infections (30) and may exert a direct effect on the yeast to enhance its virulence (18). Conversely, IL-17 signaling is clearly protective in other forms of candidiasis (31–33). Moreover, the mechanisms by which IL-17 exerts its effects in the context of candidiasis are not fully understood. IL-17 is essential to control the neutrophil and antimicrobial peptide responses to candidiasis (31, 34–36). In addition, a recent study suggests that IL-17 may also be important for driving NK cell function in disseminated disease through a mechanism dependent on granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (37).

In this study, we undertook to determine the effect of expressing IL-17A in Candida albicans during infection. We were not surprised to see that IL-17A expression reduced fungal burdens in a mouse model of disease, though it was unexpected to see that most of the beneficial effect is evident only during the first 4 days of infection (Fig. 4). This observation suggests that the most important impact of IL-17A occurs early, whereas at later stages other factors may come into play. It should be noted, however, that IL-17RA−/− mice do not recover from candidiasis even after long-term infections (7, 38), though to our knowledge, IL-17A−/− mice have not been tested in this regard. It is also possible that DAY286-IL-17A-infected mice fail to reach a threshold level of IL-17A because they are cleared rapidly during the first 4 days. Since IL-17RA serves as an essential signaling receptor for several IL-17 family cytokines (IL-17F, IL-17A/F, IL-17C, and IL-25) (39), this finding may indicate a selective effect of IL-17A during early infection.

We unexpectedly observed that the IL-17A-expressing Candida strains exhibited altered filamentation in vitro, with the IL-17A-expressing strain consistently having ∼25% shorter germ tubes than the parental strain did (Fig. 2C). The basis for this difference is unclear, though it was seen in both strains. It is possible that the additional energy expenditure required to express an additional secreted protein impacts the ability of the fungus to germinate. This finding raised the possibility that IL-17A might act directly on C. albicans, a phenomenon that was reported by Zelante and colleagues to affect Candida virulence in a gastrointestinal model of infection (18). However, when we treated the matched parental strain with IL-17A at 100 ng/ml (approximately the same concentration of cytokine produced by the recombinant strains), there was no detectable impact on germ tube growth (Fig. 2B and C). To rule out the possibility that the improved outcome in the IL-17A-producing strains was in some way related to this altered phenotype in a fungus-intrinsic manner, we evaluated candidiasis in IL-17RA−/− mice, which cannot respond to IL-17 signaling. In contrast to WT controls, there was no change in fungal load in IL-17RA−/− mice, indicating that the effect of C. albicans-produced IL-17A requires effective host responses, and thus is mediated by IL-17 signaling in host immune system (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that the impact of IL-17A is extrinsic to the fungus and support our overall conclusions that the reduced fungal loads are due to the host response to the Candida-derived cytokine.

Ectopic expression of host immune genes has been previously used as an approach to influence the immune response to fungal organisms. For example, expression of S100A8/A9 (calprotectin) in C. albicans was shown to stimulate chemotaxis of neutrophils, though not to alter virulence per se (40, 41). Wormley et al. expressed murine gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans, which conferred dramatic protection against secondary infection in a mouse model of disease (42). An intriguing translational potential application of Candida strains engineered to express immune genes is for use as a probiotic or prophylactic vaccine. C. albicans is a common commensal in humans, with a 30% colonization rate of mucosal surfaces, including skin, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, vaginal mucosa, and oral cavity. Mucosal application of the engineered strains could be used to induce protective immune responses against secondary exposure. Clearly, much further study in immunocompromised hosts would be required to evaluate the safety and efficacy of such an approach.

Antibodies to cytokines have revolutionized treatment for autoimmune disease. However, an inevitable risk with biologic therapies is infection (43). Antibodies to IL-17 and IL-17RA are currently being tested in advanced clinical trials to treat autoimmunity, and they have exhibited particularly good efficacy in psoriasis (44–47). Some patients in these trials and also individuals with naturally occurring Abs against IL-17 (e.g., patients with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome 1 arising from AIRE deficiency) develop oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) or chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) (48–50). CMC is also seen in rare individuals with mutations in genes that directly impact IL-17 signaling, including IL17RA, ACT1, or IL17F (51, 52). Although disseminated candidiasis is not typically seen in such patients, we recently found that patients taking tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors to treat rheumatoid arthritis show elevated oral colonization with C. albicans and reduced IL-17-associated immune responses (53). Thus, it is plausible that patients taking anticytokine therapies, particularly those that target the Th17/IL-17 pathway, may be at a higher risk for developing systemic candidiasis in the face of predisposing factors, such as an indwelling catheter, abdominal surgery, or long-term antibiotic use.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.L.G. was supported by NIH grants AI107825, DE022550, and DE023815. M.J.M. was supported by NIH grants DE022550-S1 and AI110822. A.P.M. was supported by NIH grant AI100270. P.S.B. was supported by UPMC and the Rheumatology Research Foundation. A.R.H. was supported by the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of the UPMC Health System and a Pediatric Infectious Disease Society Fellowship Award (funded by the Stanley A. Plotkin Sanofi Pasteur Fellowship Award) and by the Medical College of Wisconsin.

IL-17RA−/− mice were a kind gift from Amgen.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

S.L.G. has received research grants from Novartis and has consulted for or received travel reimbursements and honoraria from Novartis, Janssen, Amgen, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly. A patent has been filed describing the IL-17A-producing C. albicans strains; A.R.H., S.L.G., A.P.M., and M.J.M. are listed as inventors in the patent.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.03057-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Romani L. 2011. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 11:275–288. doi: 10.1038/nri2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glocker E, Grimbacher B. 2010. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and congenital susceptibility to Candida. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 10:542–550. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fd74f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4:165rv113. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Fidel P. 2005. The host cytokine responses and protective immunity in oropharyngeal candidiasis. J Dent Res 84:966–977. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández-Santos N, Gaffen SL. 2012. Th17 cells in immunity to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 11:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wuthrich M, Deepe GS Jr, Klein B. 2012. Adaptive immunity to fungi. Annu Rev Immunol 30:115–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. 2004. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis 190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Veerdonk FL, Kullberg BJ, Verschueren IC, Hendriks T, van der Meer JW, Joosten LA, Netea MG. 2010. Differential effects of IL-17 pathway in disseminated candidiasis and zymosan-induced multiple organ failure. Shock 34:407–411. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181d67041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saijo S, Ikeda S, Yamabe K, Kakuta S, Ishigame H, Akitsu A, Fujikado N, Kusaka T, Kubo S, Chung SH, Komatsu R, Miura N, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Shibuya K, Yamamoto N, Kawakami K, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Akira S, Iwakura Y. 2010. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity 32:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milner J, Holland S. 2013. The cup runneth over: lessons from the ever-expanding pool of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 13:635–648. doi: 10.1038/nri3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huppler AR, Bishu S, Gaffen SL. 2012. Mucocutaneous candidiasis: the IL-17 pathway and implications for targeted immunotherapy. Arthritis Res Ther 14:217. doi: 10.1186/ar3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen SC, Slavin MA, Sorrell TC. 2011. Echinocandin antifungal drugs in fungal infections: a comparison. Drugs 71:11–41. doi: 10.2165/11585270-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miceli MH, Diaz JA, Lee SA. 2011. Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. Lancet Infect Dis 11:142–151. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fidel PL Jr, Cutler JE. 2011. Prospects for development of a vaccine to prevent and control vaginal candidiasis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 13:102–107. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt CS, White CJ, Ibrahim AS, Filler SG, Fu Y, Yeaman MR, Edwards JE Jr, Hennessey JP Jr. 2012. NDV-3, a recombinant alum-adjuvanted vaccine for Candida and Staphylococcus aureus, is safe and immunogenic in healthy adults. Vaccine 30:7594–7600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin L, Ibrahim AS, Xu X, Farber JM, Avanesian V, Baquir B, Fu Y, French SW, Edwards JE Jr, Spellberg B. 2009. Th1-Th17 cells mediate protective adaptive immunity against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans infection in mice. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000703. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuthrich M, Gern B, Hung CY, Ersland K, Rocco N, Pick-Jacobs J, Galles K, Filutowicz H, Warner T, Evans M, Cole G, Klein B. 2011. Vaccine-induced protection against 3 systemic mycoses endemic to North America requires Th17 cells in mice. J Clin Invest 121:554–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI43984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zelante T, Iannitti RG, De Luca A, Arroyo J, Blanco N, Servillo G, Sanglard D, Reichard U, Palmer GE, Latge JP, Puccetti P, Romani L. 2012. Sensing of mammalian IL-17A regulates fungal adaptation and virulence. Nat Commun 3:683. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin J-J, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, Blanchard D, Gaillard C, Das Mahapatra B, Rouvier E, Golstein P, Banchereau J, Lebecque S. 1996. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J Exp Med 183:2593–2603. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods 8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, Shellito JE, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Charrier K, Peschon JJ, Kolls JK. 2001. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med 194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whibley N, Maccallum DM, Vickers MA, Zafreen S, Waldmann H, Hori S, Gaffen SL, Gow NA, Barker RN, Hall AM. 2014. Expansion of Foxp3+ T-cell populations by Candida albicans enhances both Th17-cell responses and fungal dissemination after intravenous challenge. Eur J Immunol 44:1069–1083. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkel JS, Xu W, Huang D, Hill EM, Desai JV, Woolford CA, Nett JE, Taff H, Norice CT, Andes DR, Lanni F, Mitchell AP. 2012. Portrait of Candida albicans adherence regulators. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002525. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis DA, Bruno VM, Loza L, Filler SG, Mitchell AP. 2002. Candida albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 162:1573–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruddy MJ, Shen F, Smith J, Sharma A, Gaffen SL. 2004. Interleukin-17 regulates expression of the CXC chemokine LIX/CXCL5 in osteoblasts: implications for inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. J Leukoc Biol 76:135–144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, Yamamoto H, Kasayama S, Kirkwood KL, Gaffen SL. 2004. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-a is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein family members. J Biol Chem 279:2559–2567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen F, Ruddy MJ, Plamondon P, Gaffen SL. 2005. Cytokines link osteoblasts and inflammation: microarray analysis of interleukin-17- and TNF-alpha-induced genes in bone cells. J Leukoc Biol 77:388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noble SM, Johnson AD. 2005. Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 4:298–309. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.298-309.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, Montagnoli C, Bozza S, Moretti S, Belladonna ML, Vacca C, Conte C, Mosci P, Bistoni F, Puccetti P, Kastelein RA, Kopf M, Romani L. 2007. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol 37:2695–2706. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conti H, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann M, Ho A, Hai J, Yu J, Jung J, Filler S, Masso-Welch P, Edgerton M, Gaffen S. 2009. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med 206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conti H, Peterson A, Huppler A, Brane L, Hernández-Santos N, Whibley N, Garg A, Simpson-Abelson M, Gibson G, Mamo A, Osborne L, Bishu S, Ghilardi N, Siebenlist U, Watkins S, Artis D, McGeachy M, Gaffen S. 2014. Oral-resident ‘natural’ Th17 cells and γδ-T cells control opportunistic Candida albicans infections. J Exp Med 211:2075–2084. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conti HR, Gaffen SL. 2010. Host responses to Candida albicans: Th17 cells and mucosal candidiasis. Microbes Infect 12:518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunus JM, Kazoullis A, Farah CS. 2008. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of resistance to oral Candida albicans infections. Front Biosci 13:5345–5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huppler AR, Conti HR, Hernandez-Santos N, Darville T, Biswas PS, Gaffen SL. 2014. Role of neutrophils in IL-17-dependent immunity to mucosal candidiasis. J Immunol 192:1745–1752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conti H, Baker O, Freeman A, Jang W, Li R, Holland S, Edgerton M, Gaffen S. 2011. New mechanism of oral immunity to mucosal candidiasis in hyper-IgE syndrome. Mucosal Immunol 4:448–455. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bar E, Whitney PG, Moor K, Reis e Sousa C, LeibundGut-Landmann S. 2014. IL-17 regulates systemic fungal immunity by controlling the functional competence of NK cells. Immunity 40:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernández-Santos N, Huppler AR, Peterson AC, Khader SA, McKenna KC, Gaffen SL. 2013. Th17 cells confer long term adaptive immunity to oral mucosal Candida albicans infections. Mucosal Immunol 6:900–910. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg A, Cua D. 2014. IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: discovery, mechanistic understanding and clinical therapy. Nat Rev Immunol 14:585–600. doi: 10.1038/nri3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston DA, Yano J, Fidel PL Jr, Eberle KE, Palmer GE. 2013. Engineering Candida albicans to secrete a host immunomodulatory factor. FEMS Microbiol Lett 346:131–139. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yano J, Palmer GE, Eberle KE, Peters BM, Vogl T, McKenzie AN, Fidel PL Jr. 2014. Vaginal epithelial cell-derived S100 alarmins induced by Candida albicans via pattern recognition receptor interactions are sufficient but not necessary for the acute neutrophil response during experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun 82:783–792. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00861-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wormley FL Jr, Perfect JR, Steele C, Cox GM. 2007. Protection against cryptococcosis by using a murine gamma interferon-producing Cryptococcus neoformans strain. Infect Immun 75:1453–1462. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00274-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strangfeld A, Listing J. 2006. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: bacterial and opportunistic infections during anti-TNF therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 20:1181–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, Ortonne JP, Krueger JG, Kricorian G, Aras G, Li J, Russell CB, Thompson EH, Baumgartner S. 2012. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. N Engl J Med 366:1181–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, Cameron G, Li L, Edson-Heredia E, Braun D, Banerjee S. 2012. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 366:1190–1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Genovese M, Van den Bosch F, Roberson S, Bojin S, Biagini I, Ryan P, Sloan-Lancaster J. 2010. LY2439821, a humanized anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 62:929–939. doi: 10.1002/art.27334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hueber W, Patel DD, Dryja T, Wright AM, Koroleva I, Bruin G, Antoni C, Draelos Z, Gold MH, Psoriasis Study Group, Durez P, Tak PP, Gomez-Reino JJ, Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group, Foster CS, Kim RY, Samson CM, Falk NS, Chu DS, Callanan D, Nguyen QD, Uveitis Study Group, Rose K, Haider A, Di Padova F. 2010. Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin-17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. Sci Transl Med 2:52ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kisand K, Boe Wolff AS, Podkrajsek KT, Tserel L, Link M, Kisand KV, Ersvaer E, Perheentupa J, Erichsen MM, Bratanic N, Meloni A, Cetani F, Perniola R, Ergun-Longmire B, Maclaren N, Krohn KJ, Pura M, Schalke B, Strobel P, Leite MI, Battelino T, Husebye ES, Peterson P, Willcox N, Meager A. 2010. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J Exp Med 207:299–308. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puel A, Doffinger R, Natividad A, Chrabieh M, Barcenas-Morales G, Picard C, Cobat A, Ouachee-Chardin M, Toulon A, Bustamante J, Al-Muhsen S, Al-Owain M, Arkwright PD, Costigan C, McConnell V, Cant AJ, Abinun M, Polak M, Bougneres PF, Kumararatne D, Marodi L, Nahum A, Roifman C, Blanche S, Fischer A, Bodemer C, Abel L, Lilic D, Casanova JL. 2010. Autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Exp Med 207:291–297. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, Puig L, Nakagawa H, Spelman L, Sigurgeirsson B, Rivas E, Tsai TF, Wasel N, Tyring S, Salko T, Hampele I, Notter M, Karpov A, Helou S, Papavassilis C, ERASURE Study Group, FIXTURE Study Group. 2014. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 371:326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Puel A, Cypowji S, Bustamante J, Wright J, Liu L, Lim H, Migaud M, Israel L, Chrabieh M, Audry M, Gumbleton M, Toulon A, Bodemer C, El-Baghdadi J, Whitters M, Paradis T, Brooks J, Collins M, Wolfman N, Al-Muhsen S, Galicchio M, Abel L, Picard C, Casanova J-L. 2011. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 332:65–68. doi: 10.1126/science.1200439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boisson B, Wang C, Pedergnana V, Wu L, Cypowyj S, Rybojad M, Belkadi A, Picard C, Abel L, Fieschi C, Puel A, Li X, Casanova JL. 2013. A biallelic ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity 39:676–686. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bishu S, Su E, Wilkerson E, Reckley K, Jones D, McGeachy MJ, Gaffen SL, Levesque M. 2014. Rheumatoid arthritis patients exhibit impaired Candida albicans-specific Th17 responses but preserved protective oral immunity. Arthritis Res Ther 16:R50. doi: 10.1186/ar4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.