Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype) induces interleukin-1β (IL-1β) secretion, but neither the bacterial factor triggering the activation of these inflammasome-dependent responses nor whether they are mediated by NLRP3 or NLRC4 is known. In this study, we identified a capsular polysaccharide (K1-CPS) in K. pneumoniae (NTUH-K2044, K1 serotype), isolated from a primary pyogenic liver abscess (PLA K. pneumoniae), as the Klebsiella factor that induces IL-1β secretion in an NLRP3-, ASC-, and caspase-1-dependent manner in macrophages. K1-CPS induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation through reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation, and NF-κB activation. Inhibition of both the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition and mitochondrial ROS generation inhibited K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Furthermore, IL-1β secretion in macrophages infected with PLA K. pneumoniae was shown to depend on NLRP3 but also on NLRC4 and TLR4. In macrophages infected with a K1-CPS deficiency mutant, an lipopolysaccharide (LPS) deficiency mutant, or K1-CPS and LPS double mutants, IL-1β secretion levels were lower than those in cells infected with wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae. Our findings indicate that K1-CPS is one of the Klebsiella factors of PLA K. pneumoniae that induce IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome.

INTRODUCTION

Klebsiella pneumoniae is among the most common Gram-negative bacteria infecting immunocompromised individuals and is a leading cause of community-acquired and nosocomial infections worldwide (1). In Taiwan, South Korea, North America, and Europe, K. pneumoniae also causes a newly described invasive disease, primary pyogenic liver abscess (PLA), in patients with diabetes mellitus in the absence of biliary tract diseases or other intra-abdominal infections (1, 2). Sixty to 80% of the K. pneumonia isolates causing PLA belonged to the K1 serotype in Asia (3). The major bacterial surface components that are essential for the virulence of K. pneumoniae are capsular polysaccharide (CPS) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (4–6). In a previous study, we demonstrated that CPS of the PLA-causing K. pneumoniae K1 serotype (K1-CPS) induces tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion by macrophages through the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), and that these effects are lost when pyruvation and O-acetylation of K1-CPS are chemically destroyed (7). However, the regulation of the diverse inflammatory responses elicited by K1-CPS is unclear.

The proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β is mainly secreted by activated macrophages (8). Unlike other cytokines, the secretion of mature IL-1β is controlled by caspase-1-containing multiprotein complexes called inflammasomes, which include NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2 (9–11). The best-characterized inflammasome is NLRP3, which controls caspase-1 activity and IL-1β secretion in the innate immune system (12, 13). A role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in pathogenic infections (14–16) and metabolic diseases (17–21) has been demonstrated. In addition, increasing evidence has shown that NLRP3 inflammasome has an important function in host responses to fungal, bacterial, and viral infections (22).

The mechanism of IL-1β activation by K. pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype) is unclear and was shown to involve NLRP3 in one study and NLRC4 in another. In the first study, IL-1β levels in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were lower in K. pneumoniae-infected NLRP3-deficient mice than in wild-type mice (23). In the second study, an important role for NLRC4 in host defenses against K. pneumoniae infection was demonstrated, as both IL-1β levels and caspase-1 activation in lung tissue were lower in NLRC4-deficient mice than in wild-type mice (24).

Despite recent progress in identifying the cellular mechanisms underlying the diverse host responses to K. pneumoniae infection, little is known about the Klebsiella factor regulating the inflammatory responses elicited by K. pneumoniae infection. In this study, we identified a K1-CPS from K. pneumoniae strain NTUH K-2044 (K1 serotype), isolated from a patient with PLA, as one of the Klebsiella factors that induces IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Escherichia coli LPS (from E. coli 0111:B4), ATP, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitors PD98059, SP600125, and SB203580, the phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase inhibitor LY294002, NF-κB inhibitor PDTC, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger N-acetylcysteine (NAC), the general flavoprotein inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO, the mitochondrial ROS inhibitor Mito-TEMPO, the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition inhibitor cyclosporine, and mouse antibodies against actin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). IL-1β antibody (sc-7884), NLRP3 antibody (sc-66846), caspase-1 antibody (sc-514), NF-κB inhibitory peptide sc-3060 (containing noxious liquid substance residues 360 to 369 of NF-κB p50 that inhibits translocation of the NF-κB active complex into the nucleus), control small-hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral particles, mouse NLRC4 (mNLRC4) shRNA lentiviral particles, and mTLR4 shRNA lentiviral particles were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Nigericin, glybenclamide, and shRNA plasmids for NLRP3 and ASC were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). IL-1β and TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Bacterial strains and CPS preparation.

The isolation and construction methods for wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae (strain NTUH K2044; K1-CPS+/LPS+), the PLA K. pneumoniae magA mutant (K1-CPS deficiency; K1-CPS−/LPS+), the PLA K. pneumoniae wbbO mutant (LPS deficiency; K1-CPS+/LPS−), and the PLA K. pneumoniae magA-wbbO mutants (both K1-CPS and LPS deficiency; K1-CPS−/LPS−) were descripted in our previous studies (5, 7, 25). K1-CPS isolation and the destruction of K1-CPS pyruvation and O-acetylation were performed as previously described (7). We were concerned about the possibility of LPS contamination of the K1-CPS sample. To rule out the possibility of LPS contamination during isolation, we isolated K1-CPS from the PLA K. pneumoniae wbbO mutant. After isolation, K1-CPS was further purified on a TSK HW-65F column with elution with H2O and then on an anionic DEAE-chromatograph in fast protein liquid chromatography with elution at 0 to 2 M NaCl. High-performance size-exclusion chromatography was used for the final purification, and the lower-molecular-weight incomplete LPS could be separated from the K1-CPS. In addition, LPS amounts could be measured by the 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-octonic acid (KDO)-thiobarbituric acid method, and we did not observe the KDO signal in the K1-CPS sample analyzed by nuclear magnetic resonance (data not shown). Furthermore, we used an alternative sensitive method using gas chromatography and mass analysis (GC-MS) to detect galactose in the polysaccharide fraction, as K. pneumoniae LPS is rich in galactose. Also, we did not detect the galactose in the K1-CPS sample (data not shown). K2-CPS was isolated from theK. pneumoniae (NTUH-A4528, K2 serotype) wbbO mutant, and the purification procedure was the same as that for K1-CPS (7). There is also no detectable galactose signal in K2-CPS sample analyzed by GC-MS, indicating that K2-CPS is LPS free (data not shown).

Cell cultures.

The murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 and the human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). NLRP3-, ASC-, NLRC4-, and TLR4-knockdown J774A.1 macrophages were established by transfecting the cells with specific shRNAs. After transfection, all of the shRNA-transfected cells were selected and grown in neomycin-containing medium as stable transfecting cell lines. We assumed all the selected cells contained the shRNA. All cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) and 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. To induce monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, THP-1 cells were cultured for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cytokine secretion and caspase-1 activation.

The cells were incubated for 30 min with or without inhibitor and then for 5.5 h with or without K1-CPS, K1-CPS-TFA (K1-CPS treated with 0.1 M trifluoroacetic acid [TFA] for 1 h at 90°C and then drying), K2-CPS, or E. coil LPS and then with or without 5 mM ATP or 10 μM nigericin for 0.5 h. Cytokine levels in the culture medium were measured by ELISA and activated caspase-1 (p10) and procaspase-1 (p45) levels by Western blotting.

IL-18 measurement by Western blotting.

Cell-free supernatants were extracted by the methanol-chloroform precipitation method. Briefly, 300 μl cell-free supernatants were mixed with 300 μl methanol and 125 μl chloroform. After vortexing, we added 300 μl double-distilled water to the mixture and incubated it for 10 min on ice. The mixture then was centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C, and the top layer was removed. We added 500 μl methanol and mixed the solution well, the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was dried at 55°C and dissolved in 40 μl Western blotting sample buffer followed by incubation in boiling water for 30 min. The sample was further analyzed by Western blotting.

NF-κB reporter assay.

J-Blue cells, J774A.1 macrophages stably expressing the gene for secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) inducible by NF-κB, were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells in 0.5 ml medium and grown overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. They then were pretreated with vehicle or sc-3060 for 30 min, and then 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS was added and incubation continued for 24 h. The medium then was harvested, and 20-μl aliquots were mixed with 200 μl of QUANTI-Blue medium (InvivoGen) in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. SEAP activity then was assessed by measuring the optical density at 655 nm using an ELISA reader.

NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression.

For expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, the cells were incubated for 30 min with or without inhibitor and then for 6 h with or without K1-CPS, K1-CPS-TFA, K2-CPS, or E. coil LPS, after which cellular NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β levels were measured by Western blotting.

ROS detection.

ROS generation was measured by detecting the fluorescence intensity of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein, which is the oxidation product of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Briefly, J774A.1 cells were incubated with or without 10 mM NAC or 30 nM DPI for 30 min and then with 2 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate for 30 min. The cells then were stimulated with 1 μg/ml K1-CPS for 10 min. The fluorescence intensity of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein was detected at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm on a microplate absorbance reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

RNA from macrophages was reverse transcribed prior to quantitative PCR analysis using the StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All gene expression data are presented as the relative expression normalized to that of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The primers used were the following: mouse TLR4, forward, 3′-CCTGATGACATTCCTTCT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCCACCAGATTCTCTAA-3′; mouse NLRC4, forward, 5′-CAGGTGGTCTGATTGACAGC-3′; reverse, 5′-TAGGCCTTCGGCTAGGTTTT-3′; GAPDH, forward, 5′-TGAAGGGTGGAGCCAAAAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-GATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCA-3′.

Bacterial infection.

The cells were infected with bacteria at a multiplicity of infection of 100. The number of viable bacteria used in each experiment was determined by plate counting. After incubation of the infected cells at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 1 h, extracellular bacteria were removed by washing the cells three times with PBS. The cells then were incubated in medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin to eliminate the residual extracellular bacteria. The culture medium was collected at 24 h after infection, and the IL-1β concentration in the medium was measured by ELISA.

Cell death assay.

The cells were left uninfected or were infected with PLA K. pneumoniae for 24 h or incubated with or without K1-CPS for 24 h. Cell death was determined using the alamarBlue assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (AbD Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Cell cycle determination.

Aliquots of 5 × 105 cells was fixed in 70% ethanol on ice for 2 h and centrifuged. The pellet was incubated with RNase (200 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (PI) (10 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. DNA content and cell cycle distribution were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson FACScan Plus flow cytometer. Cytofluorometric analysis was performed using a CellQuestR (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) on a minimum of 10,000 cells per sample.

Statistical analysis.

All values are reported as the means ± standard deviations (SD). The data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Scheffé test.

RESULTS

K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion through caspase-1.

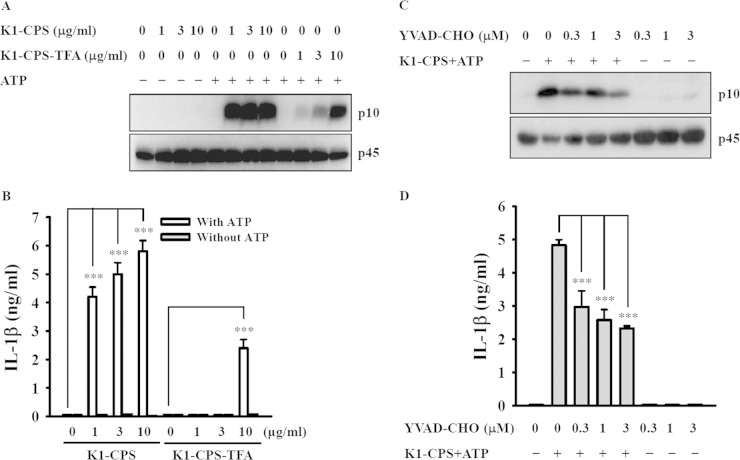

To determine whether K1-CPS is the Klebsiella factor triggering activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, we examined the effects of K1-CPS purified from the PLA K. pneumoniae wbbO mutant (LPS deficiency; K1-CPS+/LPS−, serotype K1) as reported previously (7). In mouse J774A.1 macrophages, K1-CPS induced caspase-1 activation (Fig. 1A) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 1B) in the presence of ATP. Both effects were reduced significantly when the O-acetyl and O-pyruval modifications of K1-CPS were chemically destroyed by TFA. In addition, K1-CPS-induced caspase-1 activation (Fig. 1C) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 1D) were inhibited by the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO, suggesting that K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion in a caspase-1-dependent manner.

FIG 1.

K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion through caspase-1. (A and B) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 5.5 h with or without K1-CPS or K1-CPS-TFA and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (A) and IL-1β in the culture medium (B) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. (C and D) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO, for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (C) and IL-1β in the culture medium (D) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. In panels A and C, the results are representative of three separate experiments. In panels B and D, the data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome.

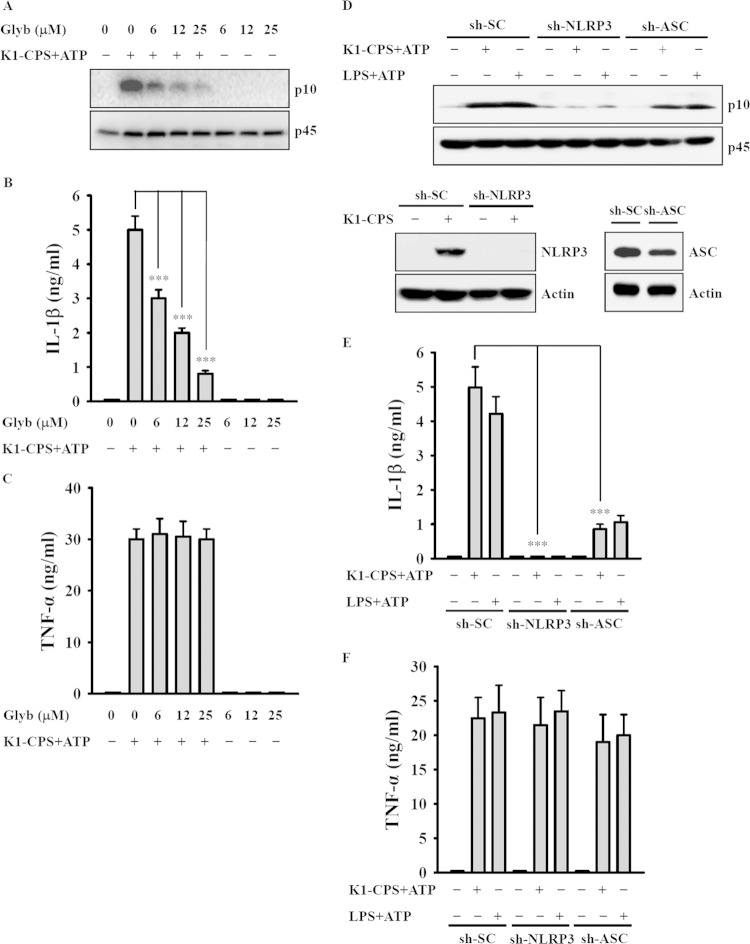

To determine whether K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome, the cells were incubated with glybenclamide, an inhibitor of NLRP3, and then treated with K1-CPS and ATP. Under these conditions, both caspase-1 activation (Fig. 2A) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 2B) were inhibited by glybenclamide in a dose-dependent manner, whereas, as expected, glybenclamide had no effect on TNF-α expression (Fig. 2C), since the latter is independent of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The reduction of NLRP3 and ASC expression by the stable transfection of J774A.1 macrophages with shRNA plasmids targeting NLRP3 (sh-NLRP3) and ASC (sh-ASC), respectively, resulted in reductions in caspase-1 activation (Fig. 2D) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 2E) induced by K1-CPS and ATP in both sh-NLRP3 cells and sh-ASC cells. There was no effect on TNF-α secretion (Fig. 2F) or in cells stably transfected with a control shRNA plasmid. The role of K1-CPS in NLRP3 inflammasome activation was confirmed in experiments using human THP-1 macrophages, in which in the presence of ATP or nigericin K1-CPS induced IL-1β (Fig. 3A) and IL-18 (Fig. 3B) secretion, whereas these effects were inhibited significantly by glybenclamide. Furthermore, in these cells, CPS from the K. pneumoniae K2 serotype (NTUH-A4528 strain) (K2-CPS) elicited similar phenotypes (Fig. 3A and B) in addition to inducing IL-1β secretion in mouse J774A.1 macrophages. The latter effect was inhibited by NLRP3 knockdown (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results indicate that K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome.

FIG 2.

K1-CPS induces IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome. (A to C) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without the NLRP3 inhibitor glybenclamide (Glyb), for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (A), IL-1β in the culture medium (B), and TNF-α in the culture medium (C) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. (D to F) J774A.1 macrophages stably transfected with a control shRNA plasmid (sh-SC), an NLRP3 shRNA plasmid (sh-NLRP3), and an ASC shRNA plasmid (sh-ASC) were incubated for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS or LPS and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (D), IL-1β in the culture medium (E), and TNF-α in the culture medium (F) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. In panels A and D, the results are representative of three separate experiments. In panels B, C, E, and F, the data are expressed as means ± SD from three separate experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

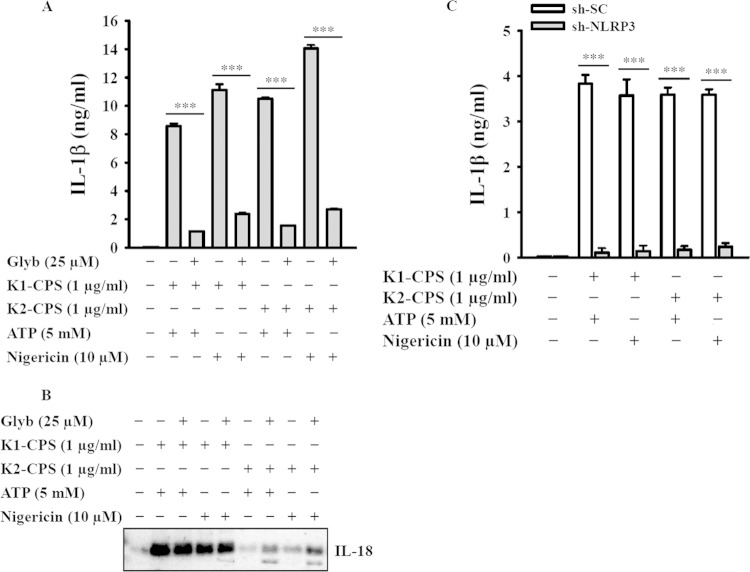

FIG 3.

K1-CPS and K2-CPS induce IL-1β and IL-18 secretion through NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages. (A and B) Human THP-1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without NLRP3 inhibitor glybenclamide (Glyb), for 5.5 h with or without K1-CPS or K2-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without ATP or nigericin. The levels of IL-1β (A) and IL-18 (B) in the culture medium were measured by ELISA and Western blotting, respectively. (C) sh-SC and sh-NLRP3 J774A.1 cells were incubated for 5.5 h with or without K1-CPS or K2-CPS and then for 30 min with or without ATP or nigericin. The levels of IL-1β in the culture medium were measured by ELISA. In panels A and C, the data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. In panel B, the results are representative of three separate experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

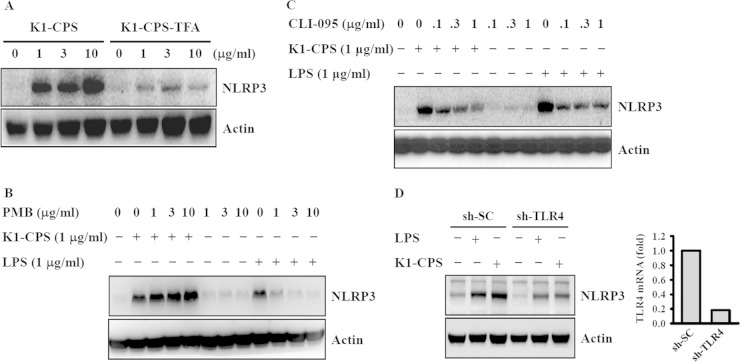

K1-CPS induces NLRP3 expression through TLR4.

NLRP3 induction is a critical checkpoint for the priming step of NLRP3 inflammasome activation (26, 27). To investigate whether K1-CPS induces the priming signal for the NLRP3 inflammasome, J774A.1 macrophages were incubated with K1-CPS for 6 h and NLRP3 expression then was measured. The results showed an increase in NLRP3 levels that could be reduced significantly when the O-acetyl and O-pyruval modifications of K1-CPS were chemically destroyed by TFA (Fig. 4A). To rule out the possibility of LPS contamination in our K1-CPS preparation, we tested the effect of polymyxin B, an antibiotic used to neutralize LPS activity, on K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 expression (7). Polymyxin B significantly inhibited E. coli LPS-induced but not K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 expression (Fig. 4B), confirming that the K1-CPS preparations used in this study were LPS free. In previous work, we showed that K1-CPS induces TNF-α and IL-6 secretion partially through TLR4 (7). Thus, in the present study, we asked whether TLR4 is also involved in K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 expression. By treating the J774A.1 macrophages with CLI-095, a cyclohexene derivative that specifically suppresses TLR4 signaling (28), we found that both K1-CPS- and E. coli LPS-induced NLRP3 expression were inhibited (Fig. 4C). The role of TLR4 in K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 expression was confirmed, as K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 expression was significantly lower in cells stably transfected with shRNA plasmids targeting TLR4 (sh-TLR4) than in sh-SC cells (Fig. 4D). These experiments provided evidence that K1-CPS induces the priming signal of the NLRP3 inflammasome partially through TLR4.

FIG 4.

K1-CPS induces NLRP3 expression through TLR4. (A) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 6 h with or without K1-CPS or K1-CPS-TFA. The levels of NLRP3 in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (B) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without polymyxin B (PMB) and then for 6 h with or without K1-CPS or LPS. The levels of NLRP3 in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (C) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without TLR4 inhibitor CLI-095 and then for 6 h with or without K1-CPS or LPS. The levels of NLRP3 in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (D) sh-SC and sh-TLR4 J774A.1 cells were incubated for 6 h with or without K1-CPS or LPS. The levels of NLRP3 in the cells were measured by Western blotting. TLR4 mRNA expression in the knockdown cells is also shown (right). The results are representative of three separate experiments.

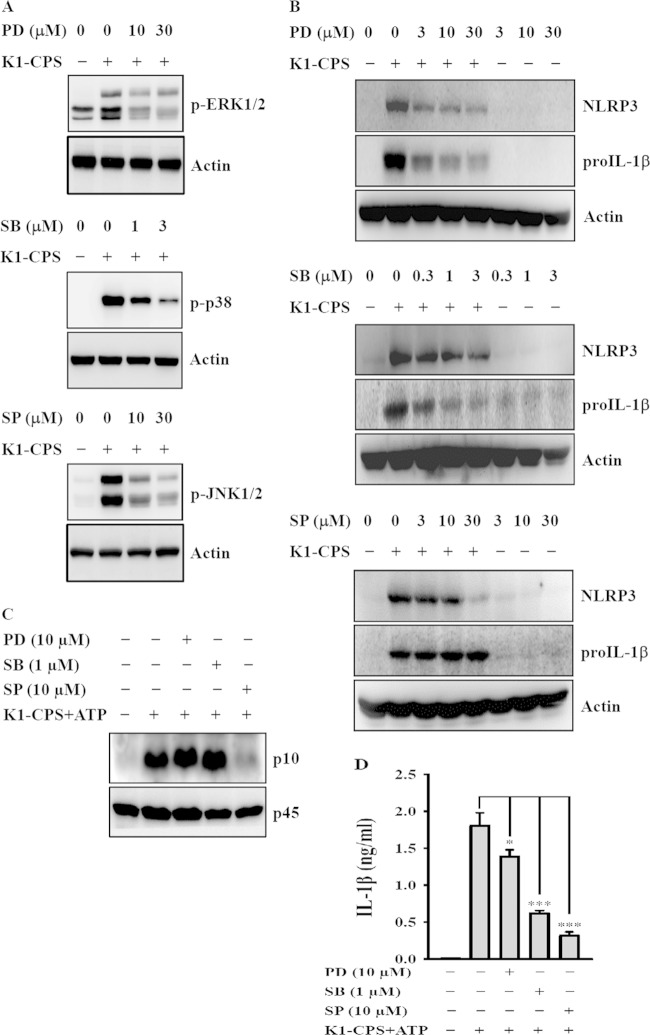

Effect of MAPK on K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion are affected by both a priming signal from pathogen-associated molecular patterns (e.g., LPS) and an activation signal from a second stimulus (e.g., ATP), the former controlling the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β and the latter controlling caspase-1 activation (10, 13). We previously demonstrated that K1-CPS induces the activation of MAPK, including ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38, in macrophages (7). Here, we showed that K1-CPS induces phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38, and these effects were reduced by the specific inhibitors PD98059 (MEK1 inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK1/2 inhibitor), and SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), respectively (Fig. 5A). To examine whether MAPK is involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in K1-CPS-activated macrophages, J774A.1 macrophages were preincubated with the MAPK inhibitors for 30 min and then stimulated with K1-CPS for 6 h. Our data showed that ERK1/2 and p38 are required for the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, as PD98059 and SB203580 significantly reduced the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β in K1-CPS-activated macrophages (Fig. 5B). However, ERK1/2 and p38 are not required for the caspase-1 activation, as PD98059 and SB203580 did not reduce active caspase-1 (p10) expression in K1-CPS-plus-ATP-activated macrophages (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that ERK1/2 and p38 control the priming signal of NLRP3 inflammasome (NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression) but do not affect the activation signal of the NLRP3 inflammasome (caspase-1 activation). These results indicate that PD98059 and SB203580 reduced IL-1β secretion (Fig. 5D), possibly through inhibiting pro-IL-1β expression (Fig. 5B). Regarding the role of JNK1/2 in NLRP3 inflammasome activation, JNK1/2 inhibitor (SP600125) did not inhibit the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β significantly in K1-CPS-activated macrophages (Fig. 5B), but it significantly inhibited caspase-1 activation (Fig. 5C) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 5D) in K1-CPS-ATP-activated macrophages. These results indicate that SP60012 reduced IL-1β secretion mainly through inhibiting caspase-1 activation.

FIG 5.

Effect of MAPK on K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. (A) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without MAPK inhibitors PD, SB, and SP and then for 15 min with or without K1-CPS. The phosphorylation levels of MAPK in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (B) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without MAPK inhibitors PD, SB, and SP and then for 6 h with or without K1-CPS. The levels of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (C and D) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without PD, SB, and SP, for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (C) and IL-1β in the culture medium (D) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. In panels A to C, the results are representative of three separate experiments. In panel D, the data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

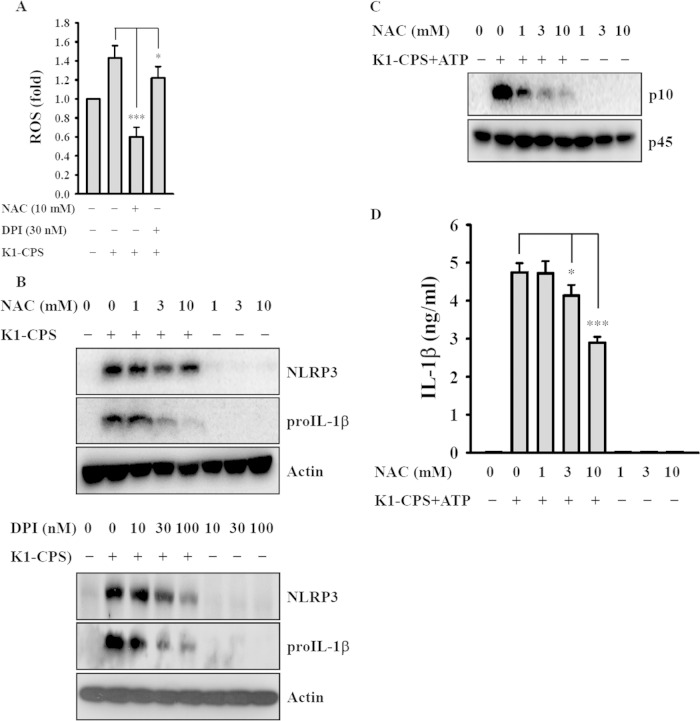

Effect of ROS on K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

ROS has been shown to play an important role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation (27, 29). We found that K1-CPS induced ROS generation in macrophages and that this effect was inhibited by the ROS scavenger NAC as well as by the general flavoprotein inhibitor DPI (Fig. 6A). These two inhibitors also significantly reduced pro-IL-1β expression, but they only slightly reduced NLRP3 expression in K1-CPS-activated macrophages (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the association between ROS production and NLRP3 expression is weak. In addition, NAC inhibited K1-CPS-mediated caspase-1 activation (Fig. 6C) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that NAC reduces IL-1β secretion mainly through inhibiting pro-IL-1β expression (Fig. 6B) and caspase-1 activation (Fig. 6C) but not through inhibiting NLRP3 expression. These results indicate that K1-CPS mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation partially through ROS-associated pathways.

FIG 6.

Effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. (A) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without NAC or DPI, for 30 min with 2 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate, and then for 10 min with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS. ROS generation in the cells was measured by 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate. (B) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without NAC or DPI and then for 6 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS. The levels of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (C and D) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without NAC, for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (C) and IL-1β in the culture medium (D) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. In panels A and D, the data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. In panels B and C, the results are representative of three separate experiments. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

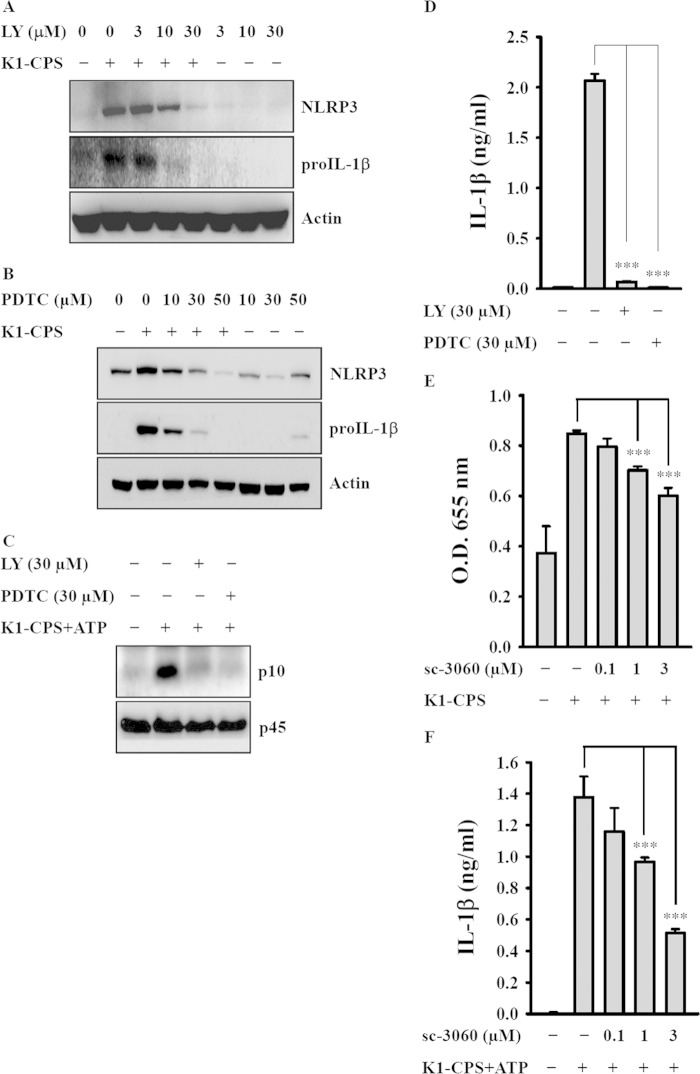

Effect of PI3-kinase and NF-κB on K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

K1-CPS induced activation of NF-κB is inhibited by LY294002, a PI3-kinase inhibitor (7). In the present study, both LY294002 and PDTC, an NF-κB inhibitor, prevented K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting that the PI3-kinase/NF-κB signaling pathway positively regulates NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression in K1-CPS-activated macrophages. LY294002 and PDTC also inhibited K1-CPS-mediated caspase-1 activation (Fig. 7C) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 7D), consistent with the essential involvement of PI3-kinase and NF-κB in K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The role of NF-κB in K1-CPS-mediated IL-1β secretion was confirmed by using a synthetic cell-permeable NF-κB inhibitory peptide, as this peptide significantly inhibited K1-CPS-mediated NF-κB activation (Fig. 7E) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 7F).

FIG 7.

Effect of phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase and NF-κB on K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. (A and B) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without LY294002 (LY) (A) or PDTC (B) and then for 6 h with or without K1-CPS. The levels of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β in the cells were measured by Western blotting. (C and D) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without LY or PDTC, for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (C) and IL-1β in the culture medium (D) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. (E) J-Blue cells were incubated for 30 min with or without sc-3060 and then for 24 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS. The activation levels of NF-κB were measured by an NF-κB reporter assay. (F) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without sc-3060, for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of IL-1β in the culture medium were measured by ELISA. In panels A to C, the results are representative of three separate experiments. In panels D to F, the data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

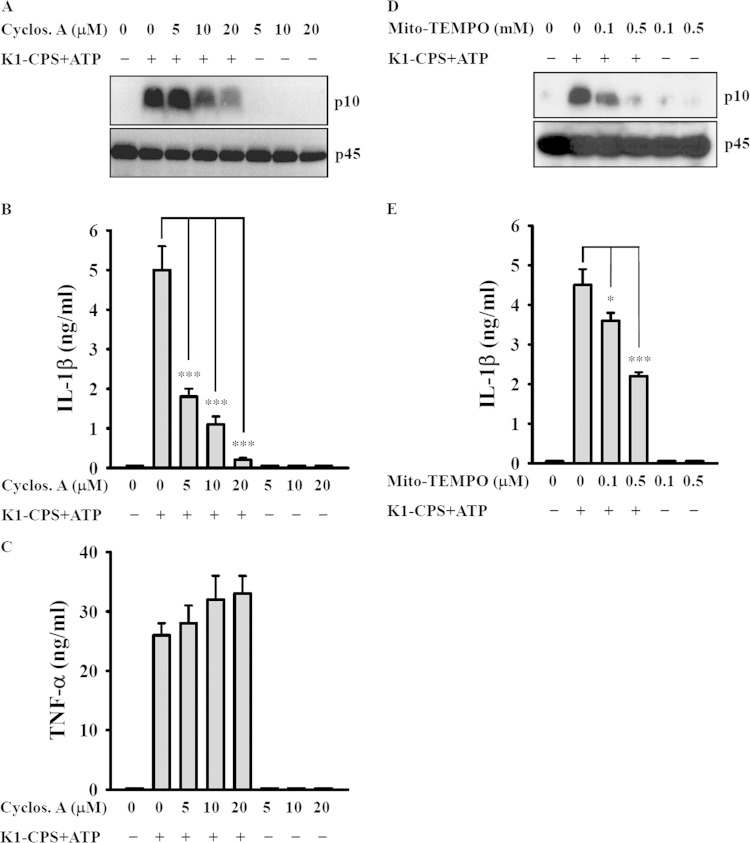

Role of mitochondria in K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Inducers of NLRP3 trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation via a mitochondrial membrane permeability transition and mitochondrial ROS generation (30–33). In experiments using cyclosporine, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition (31), we found that K1-CPS-induced caspase-1 activation (Fig. 8A) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 8B), but not TNF-α secretion (Fig. 8C), was inhibited by cyclosporine. K1-CPS-induced caspase-1 activation (Fig. 8D) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 8E) also were inhibited by Mito-TEMPO, an inhibitor of mitochondrial ROS. These results strongly suggest the importance of mitochondrial integrity in K1-CPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

FIG 8.

Effect of mitochondria on K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. (A to C) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without cyclosporine (Cyclos. A), for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (A), IL-1β in the culture medium (B), and TNF-α in the culture medium (C) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. (D and E) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 30 min with or without Mito-TEMPO, for 5.5 h with or without 1 μg/ml of K1-CPS, and then for 30 min with or without 5 mM ATP. The levels of activated caspase-1 (p10) in the cells (D) and IL-1β in the culture medium (E) were measured by Western blotting and ELISA, respectively. In panels A and D, the results are representative of three separate experiments. In panels B, C, and E, the data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. *, P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001.

K. pneumoniae infection induces IL-1β secretion partially through the NLRP3 inflammasome.

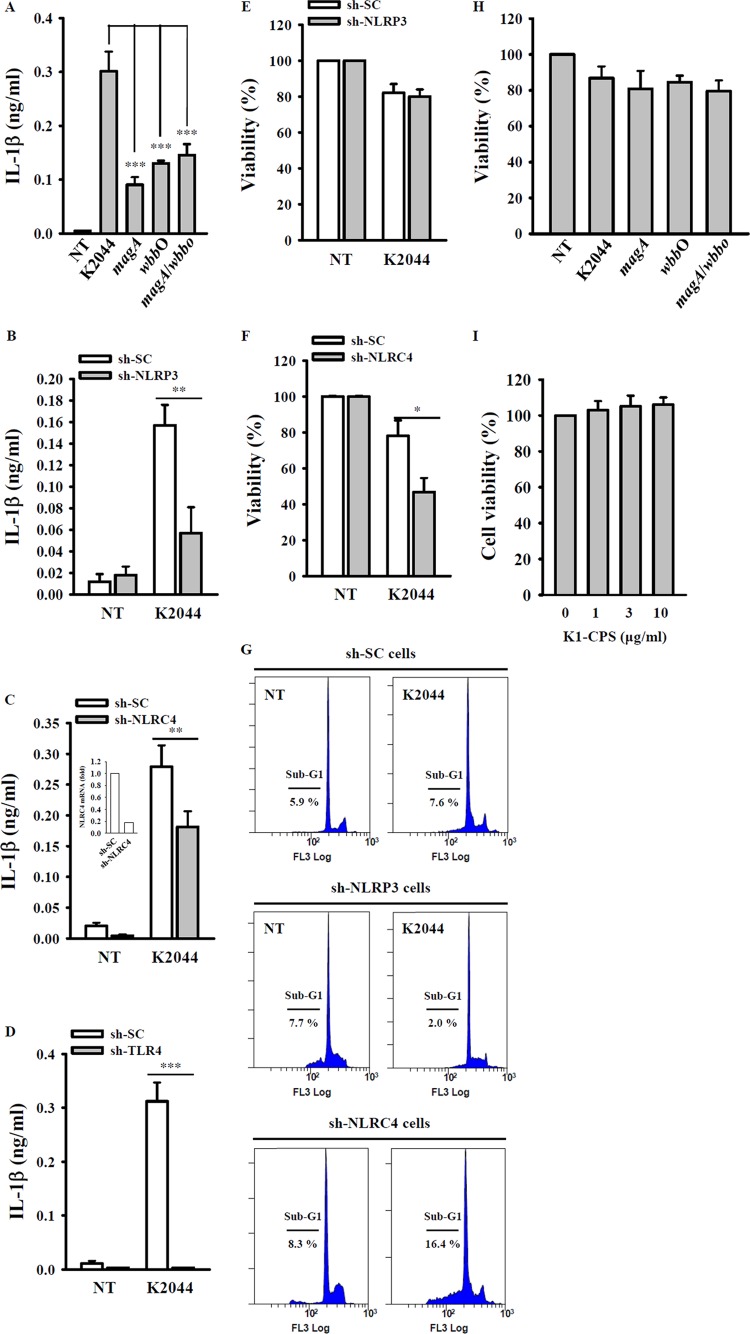

CPS and LPS are important virulence factors of K. pneumoniae (4–6). To investigate whether the induction of IL-1β secretion during K. pneumoniae infection is K1-CPS dependent, we measured the levels of IL-1β in the culture medium of J774A.1 macrophages infected with wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae, the PLA K. pneumoniae magA mutant, the PLA K. pneumoniae wbbO mutant, or the PLA K. pneumoniae magA-wbbO mutants. While all of these strains induced IL-1β secretion significantly, the level of secretion induced by the magA mutant, wbbO mutant, and magA-wbbO mutants was lower than that induced by wild-type K. pneumoniae (Fig. 9A). However, IL-1β secretion levels induced by these three mutants were not significantly different. Thus, both K1-CPS and LPS appear to be involved in IL-1β secretion during PLA K. pneumoniae infection. Further evidence that NLRP3 regulated IL-1β secretion in wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae-infected macrophages was obtained from NLRP3 knockdown cells, in which IL-1β secretion was reduced significantly (Fig. 9B). A previous study showed that NLRC4 is important for IL-1β induction in K. pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype)-infected macrophages (24). Consistent with that report, we found that IL-1β secretion following PLA K. pneumoniae infection was lower in NLRC4 knockdown macrophages than in control macrophages (Fig. 9C). IL-1β secretion induced by PLA K. pneumoniae infection also was found to depend on TLR4 expression, as secretion was inhibited completely in TLR4 knockdown cells (Fig. 9D). Infection with K. pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype) was previously shown to induce cell death in THP-1 macrophages in an NLRP3-dependent manner (23). However, according to our results, cell death induced by PLA K. pneumoniae infection was independent of NLRP3, as there was no change in cell death in NLRP3 knockdown cells versus control cells (Fig. 9E). Interestingly, cell death in NLRC4 knockdown cells was higher than that in control cells after PLA K. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 9F). The effects of NLRP3 and NLRC4 on cell death induced by PLA K. pneumoniae infection were confirmed by cell cycle analysis using PI staining (Fig. 9G). In addition, cell death induced by PLA K. pneumoniae infection was independent of K1-CPS and LPS, as there was no significant difference in the levels of cell death after wild-type, magA mutant, wbbo mutant, and magA-wbbO mutant PLA K. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 9H). Furthermore, K1-CPS per se had no effect on cell viability (Fig. 9I). Taken together, these results clearly show that K1-CPS is not involved in the cell death induced by K. pneumoniae infection.

FIG 9.

K. pneumoniae infection induces IL-1β secretion partially through NLRP3 inflammasome. (A) J774A.1 macrophages infected with or without wild-type, magA mutant, wbbO mutant, or magA-wbbO mutant PLA K. pneumoniae for 24 h. The levels of IL-1β in the culture medium were measured by ELISA. (B to D) sh-SC and sh-NLRP3 (B), sh-SC and sh-NLRC4 (C), or sh-SC and sh-TLR4 (D) J774A.1 cells left uninfected or infected with wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae for 24 h. The levels of IL-1β in the culture medium were measured by ELISA. (E and F) sh-SC and sh-NLRP3 (E) or sh-SC and sh-NLRC4 (F) J774A.1 cells infected with or without wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae for 24 h. The cell viability was measured by alamarBlue assay. (G) sh-SC, sh-NLRP3, and sh-NLRC4 J774A.1 cells left uninfected or infected with wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae for 24 h. The cell viability was measured by cell cycle (sub-G1) analysis using PI staining. (H) J774A.1 macrophages left uninfected or infected with wild-type, magA mutant, wbbO mutant, or magA-wbbO mutant PLA K. pneumoniae for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by alamarBlue assay. (I) J774A.1 macrophages were incubated for 24 h with or without K1-CPS. The cell viability was measured by alamarBlue assay. The data are expressed as the means ± SD from three separate experiments. NT, no treatment. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Inflammasome activation contributes to host defense by inducing cytokine production, which limits microbial invasion during infection; however, the overactivation of inflammasomes is associated with autoinflammatory disease. Thus, dissecting the inflammasome pathways may improve our understanding of the mechanisms of host defense against microbes and of the development of inflammatory disease. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in mediating pathogen-induced inflammation has been clearly demonstrated in several studies, but little is known about the active components of the pathogen that are necessary for NLRP3 inflammasome activation (34). In this work, we showed that K1-CPS is the virulence factor of PLA K. pneumoniae (NTUH K-2044, K1 serotype) and that it induces IL-1β secretion in human THP-1 macrophages and mouse J774A.1 macrophages by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. This finding is supported by the results of macrophages infected with the PLA K. pneumoniae magA mutant (K1-CPS deficiency; K1-CPS−/LPS+), in which IL-1β secretion was significantly lower than that following infection with wild-type PLA K. pneumoniae.

K. pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype) infection was shown previously to stimulate IL-1β and HMGB1 release in mouse macrophages in a process dependent on NLRP3 and ASC but not on NLRC4 (23). In the same study, LPS isolated from the infecting strain of K. pneumonia induced IL-1β secretion in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages, and the effect was reduced significantly in cells from NLRP3 and ASC knockout mice but not from those of NLRC4 knockout mice (23). However, another study showed that knockdown of NLRC4 reduced IL-1β secretion from macrophages infected by the same strain of K. pneumonia (24). Our results are in agreement with both studies, as we found that PLA K. pneumoniae induces IL-1β secretion through NLRP3 and through NLRC4. In contrast, NLRP12, a newly defined inflammasome that acts as a negative regulator of inflammation, does not significantly contribute to the in vivo host innate immune response to K. pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype) infection (35). Willingham et al. observed cell death following the infection of THP-1 human monocytic cells with K. pneumoniae (strain 43816, K2 serotype), and this effect was abrogated in THP-1 human monocytic cells with reduced NLRP3 expression (23). We found that NLRP3 was not shown to mediate cell death in the PLA K. pneumoniae (NTUH K-2044, K1 serotype) infection cell model, as there was no change in cell death in NLRP3 knockdown cells versus control cells. Unexpectedly, PLA K. pneumoniae infection induces more cell death in NLRC4 knockdown J774A.1 macrophages than in control cells. It has been reported that NLRP4 negatively regulates autophagic response (36, 37). We speculate that PLA K. pneumoniae infection induces more cell death in NLRC4 knockdown cells, probably resulting from more autophagic cell death; however, the detailed mechanism needs further investigation.

NLRP3 expression is necessary, but not sufficient, for caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release; rather, an essential activation signal is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation (26, 27). We found that K1-CPS does not activate the NLRP3 inflammasome directly; instead, it primes the inflammasome by inducing NLRP3 expression through ERK1/2-, JNK1/2-, and p38-dependent pathways. This is in contrast to LPS from Escherichia coli, which induces NLRP3 expression through ERK1/2- and JNK1/2-dependent, but p38-independent, pathways (38). These results suggest that K1-CPS and LPS regulate NLRP3 expression through similar, but not identical, pathways. We previously demonstrated that K1-CPS induces TNF-α and IL-6 secretion via TLR4, and that these effects require the pyruvation and O-acetylation of K1-CPS (7). In this study, we found that TLR4 controls not only the expression of NLRP3 in K1-CPS-activated macrophages but also IL-1β secretion in PLA K. pneumoniae-infected macrophages. It should be noted that K1-CPS activates macrophages partially through TLR4, and other receptors probably are involved. K1-CPS pyruvation and O-acetylation also were shown to be important for K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

ROS contribute to NLRP3 inflammasome activation, as ROS inhibitor inhibits the priming signal of the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-activated macrophages (27, 30). Here, we found that the ROS inhibitor NAC reduced K1-CPS-induced IL-1β secretion through inhibiting caspase-1 activation (activation signal of NLRP3 inflammasome) and pro-IL-1β expression but not through inhibiting NLRP3 expression. However, according to van Bruggen et al., human NLRP3 inflammasome activation is independent of Nox1-4, an important enzyme in ROS production (39). Mitochondria are another source of cellular ROS, and their overproduction promotes a mitochondrial permeability transition as well as the cytosolic release of mitochondrial DNA, which stimulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation (30–33). In our study, the mitochondrial ROS inhibitor Mito-TEMPO inhibited K1-CPS-mediated caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion. Notably, Mito-TEMPO reduced K1-CPS-induced TNF-α secretion significantly, whereas in a previous study Mito-TEMPO had no effect on LPS-induced TNF-α secretion (31).

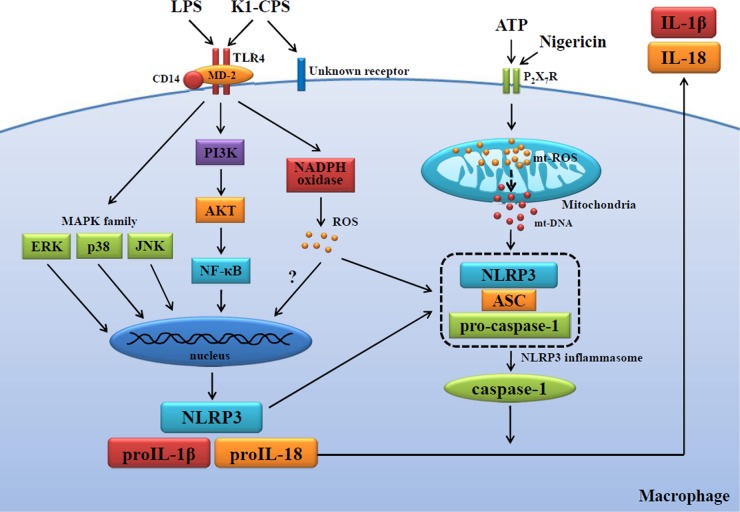

In patients with type 2 diabetes, NLRP3 inflammasome activation plays an important role in the sensing of obesity-associated danger signals and contributes to obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance (40–42). Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide, responsible for the amyloid deposits that form in the pancreas during type 2 diabetes, results in the generation of mature IL-1β, which induces apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells (43). There are case reports of Taiwanese patients with PLA K. pneumoniae-positive liver abscesses with no history of hepatobiliary disease; however, 70% of these patients have diabetes mellitus (44, 45). Here, we showed that PLA K. pneumoniae infection induces IL-1β secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome, providing a possible mechanism for the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, in which there is an initial infection by PLA K. pneumoniae, as well as a potential mechanism explaining the predisposition of these patients to the development of liver abscesses. In conclusion, our results provide insight into how PLA K. pneumoniae K1-CPS regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. 10) and, in turn, a molecular rationale for future therapeutic interventions in PLA K. pneumonia infection.

FIG 10.

Proposed mechanism of K1-CPS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under contract grant numbers 98-2320-B-197-003-MY2, 102-2628-B-197-001-MY3, 103-2923-B-197-001-MY3, 102-2325-B-001-020, and 103-2325-B-001-020.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ, Hansen DS, Von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Casellas JM, Goossens H, Mulazimoglu L, Trenholme G, Klugman KP, McCormack JG, Yu VL. 2002. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg Infect Dis 8:160–166. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang CC, Yen CH, Ho HW, Wang JH. 2004. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscess due to non-Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 37:176–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung DR, Lee SS, Lee HR, Kim HB, Choi HJ, Eom JS, Kim JS, Choi YH, Lee JS, Chung MH, Kim YS, Lee H, Lee MS, Park CK. 2007. Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J Infect 54:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomas JM, Camprubi S, Merino S, Davey MR, Williams P. 1991. Surface exposure of O1 serotype lipopolysaccharide in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains expressing different K antigens. Infect Immun 59:2006–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang CT, Chuang YP, Shun CT, Chang SC, Wang JT. 2004. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J Exp Med 199:697–705. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortés G, Borrell N, de Astorza B, Gómez C, Sauleda J, Albertí S. 2002. Molecular analysis of the contribution of the capsular polysaccharide and the lipopolysaccharide O side chain to the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a murine model of pneumonia. Infect Immun 70:2583–2590. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2583-2590.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang FL, Yang YL, Liao PC, Chou JC, Tsai KC, Yang AS, Sheu F, Lin TL, Hsieh PF, Wang JT, Hua KF, Wu SH. 2011. Structure and immunological characterization of the capsular polysaccharide of a pyrogenic liver abscess caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae: activation of macrophages through Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem 286:21041–21051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello CA. 1997. Interleukin-1. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 8:253–265. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(97)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. 2009. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol 27:229–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroder K, Tschopp J. 2010. The inflammasomes. Cell 140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. 2011. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassel SL, Joly S, Sutterwala FS. 2009. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor of immune danger signals. Semin Immunol 21:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin C, Flavell A. 2010. Molecular mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Clin Immunol 30:628–631. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanneganti TD, Ozören N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Akira S, Núñez G. 2006. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature 440:233–236. doi: 10.1038/nature04517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, Guthrie EH, Pickles RJ, Ting JP. 2009. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 30:556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschläger N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Mocsai A, Tschopp J, Ruland J. 2009. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 459:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. 2006. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E. 2008. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT. 2008. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol 9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nuñez G, Schnurr M, Espevik T, Lien E, Fitzgerald KA, Rock KL, Moore KJ, Wright SD, Hornung V, Latz E. 2010. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM, Dixit VD. 2011. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med 17:179–188. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Kanneganti TD. 2011. Role of the nlrp3 inflammasome in microbial infection. Front Microbiol 2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willingham SB, Allen IC, Bergstralh DT, Brickey WJ, Huang MT, Taxman DJ, Duncan JA, Ting JP. 2009. NLRP3 (NALP3, Cryopyrin) facilitates in vivo caspase-1 activation, necrosis, and HMGB1 release via inflammasome-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol 183:2008–2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai S, Batra S, Wakamatsu N, Pacher P, Jeyaseelan S. 2012. NLRC4 inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1β modulates mucosal immunity in the lung against gram-negative bacterial infection. J Immunol 188:5623–5635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh PF, Lin TL, Lee CZ, Tsai SF, Wang JT. 2008. Serum-induced iron-acquisition systems and TonB contribute to virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary pyogenic liver abscess. J Infect Dis 197:1717–1727. doi: 10.1086/588383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA, Hornung V, Latz E. 2009. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol 183:787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauernfeind F, Bartok E, Rieger A, Franchi L, Núñez G, Hornung V. 2011. Cutting edge: reactive oxygen species inhibitors block priming, but not activation, of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. J Immunol 187:613–617. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ii M, Matsunaga N, Hazeki K, Nakamura K, Takashima K, Seya T, Hazeki O, Kitazaki T, Iizawa Y. 2006. A novel cyclohexene derivative, ethyl (6R)-6-[N-(2-chloro-4-fluorophenyl) sulfamoyl]cyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylate (TAK-242), selectively inhibits toll-like receptor 4-mediated cytokine production through suppression of intracellular signaling. Mol Pharmacol 69:1288–1295. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su SC, Hua KF, Lee H, Chao LK, Tan SK, Lee H, Yang SF, Hsu HY. 2006. LTA and LPS mediated activation of protein kinases in the regulation of inflammatory cytokines expression in macrophages. Clin Chim Acta 374:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tschopp J, Schroder K. 2010. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: the convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat Rev Immunol 10:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nri2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kepp O, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. 2011. Mitochondrial control of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 12:199–200. doi: 10.1038/ni0311-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, Englert JA, Rabinovitch M, Cernadas M, Kim HP, Fitzgerald KA, Ryter SW, Choi AM. 2011. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. 2011. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franchi L, Muñoz-Planillo R, Núñez G. 2012. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol 13:325–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen IC, McElvania-TeKippe E, Wilson JE, Lich JD, Arthur JC, Sullivan JT, Braunstein M, Ting JP. 2013. Characterization of NLRP12 during the in vivo host immune response to Klebsiella pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 8:e60842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Shiina M, Ogata K, Ishii KJ, Takeshita F. 2011. NLRP4 negatively regulates autophagic processes through an association with beclin1. J Immunol 186:1646–1655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdelaziz DH, Amr K, Amer AO. 2010. Nlrc4/Ipaf/CLAN/CARD12: more than a flagellin sensor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:789–791. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao PC, Chao LK, Chou JC, Dong WC, Lin CN, Lin CY, Chen A, Ka SM, Ho CL, Hua KF. 2013. Lipopolysaccharide/adenosine triphosphate-mediated signal transduction in the regulation of NLRP3 protein expression and caspase-1-mediated interleukin-1β secretion. Inflamm Res 62:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Bruggen R, Köker MY, Jansen M, van Houdt M, Roos D, Kuijpers TW. 2010. Human NLRP3 inflammasome activation is Nox1-4 independent. Blood 115:5398–5400. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee HM, Kim JJ, Kim HJ, Shong M, Ku BJ, Jo EK. 2013. Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 62:194–204. doi: 10.2337/db12-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jourdan T, Godlewski G, Cinar R, Bertola A, Szanda G, Liu J, Tam J, Han T, Mukhopadhyay B, Skarulis MC, Ju C, Aouadi M, Czech MP, Kunos G. 2013. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in infiltrating macrophages by endocannabinoids mediates beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med 19:1132–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. 2011. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, Hull RL, Tannahill GM, Sharp FA, Becker C, Franchi L, Yoshihara E, Chen Z, Mullooly N, Mielke LA, Harris J, Coll RC, Mills KH, Mok KH, Newsholme P, Nuñez G, Yodoi J, Kahn SE, Lavelle EC, O'Neill LA. 2010. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol 11:897–904. doi: 10.1038/ni.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang CC, Chen CY, Lin XZ, Chang TT, Shin JS, Lin CY. 1993. Pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan: emphasis on gas-forming liver abscess in diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol 88:1911–1915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng DL, Liu YC, Yen MY, Liu CY, Wang RS. 1991. Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med 151:1557–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]