Abstract

In recent years there has been an increased interest in pain neuroscience in physical therapy.1,2 Emerging pain neuroscience research has challenged prevailing models used to understand and treat pain, including the Cartesian model of pain and the pain gate.2–4 Focus has shifted to the brain's processing of a pain experience, the pain neuromatrix and more recently, cortical reorganisation of body maps.2,3,5,6 In turn, these emerging theories have catapulted new treatments, such as therapeutic neuroscience education (TNE)7–10 and graded motor imagery (GMI),11,12 to the forefront of treating people suffering from persistent spinal pain. In line with their increased use, both of these approaches have exponentially gathered increasing evidence to support their use.4,10 For example, various randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews have shown that teaching patients more about the biology and physiology of their pain experience leads to positive changes in pain, pain catastrophization, function, physical movement and healthcare utilisation.7–10 Graded motor imagery, in turn, has shown increasing evidence to help pain and disability in complex pain states such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).11,12 Most research using TNE and GMI has focussed on chronic low back pain (CLBP) and CRPS and none of these advanced pain treatments have been trialled on the thoracic spine. This lack of research and writings in regards to the thoracic spine is not unique to pain science, but also in manual therapy. There are, however, very unique pain neuroscience issues that skilled manual therapists may find clinically meaningful when treating a patient struggling with persistent thoracic pain. Utilising the latest understanding of pain neuroscience, three key clinical chronic thoracic issues will be discussed – hypersensitisation of intercostal nerves, posterior primary rami nerves mimicking Cloward areas and mechanical and sensitisation issues of the spinal dura in the thoracic spine.

Keywords: Pain, Chronic, Thoracic, Neuroscience, Sensitisation

Hypersensitvity of the Intercostal Nerves Following Injury

Rib injuries, including fractures, are common during injury or trauma associated with the thoracic spine.13,14 This can result from sports injuries, fractures or even invasive medical procedures such as cardiothoracic surgery.13,14 Traditional wisdom implies that following the initial insult, the normal phases of healing (bleeding, inflammation, remodelling and scarring), will lead to a pain-free recovery.15 This is true in many cases, but some patients with persistent thoracic pain experience pain not only well after the normal phases of healing, but also experience increased levels of pain and disability over time.16 Increasing evidence supports a hypervigilant nervous system as a significant source of persistent pain following traditional orthopaedic injuries.17,18 This upregulation of the peripheral nervous system is referred to as peripheral neuropathic pain and characterised by pain in dermatomes or cutaneous distribution, positive neurodynamic tests, positive palpation sensitivity and a history consistent with nerve pathology or compromise.17

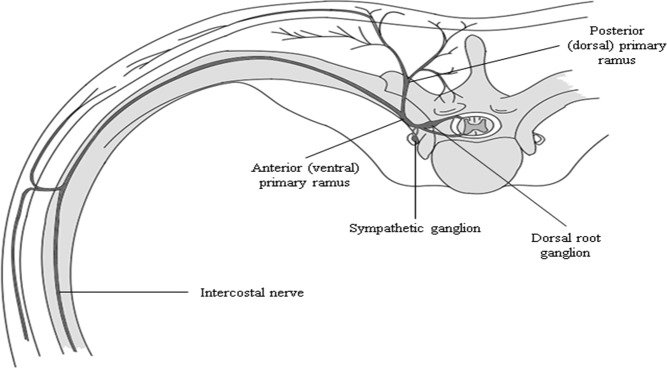

Although multi-factorial, peripheral neuropathic pain in the thoracic spine should also be viewed from the perspective of changes in ion channel expression in axons associated with nerves having undergone physical and physiological changes due to trauma, such as rib fractures, bleeding and development of scar tissue. From an anatomical perspective, the thoracic spine, lends itself to such potential mechanisms.14 The intercostal nerves originate from the anterior roots of the thoracic spinal nerves from T1 to T11. The first two nerves supply the upper limbs, while the intercostal nerves below T2 follow the intercostal spaces, intertwined between blood vessels, membranes and muscles (Fig. 1).14

Figure 1.

Anatomical considerations of the intercostal and posterior primary ramus nerve supply in the thoracic spine.

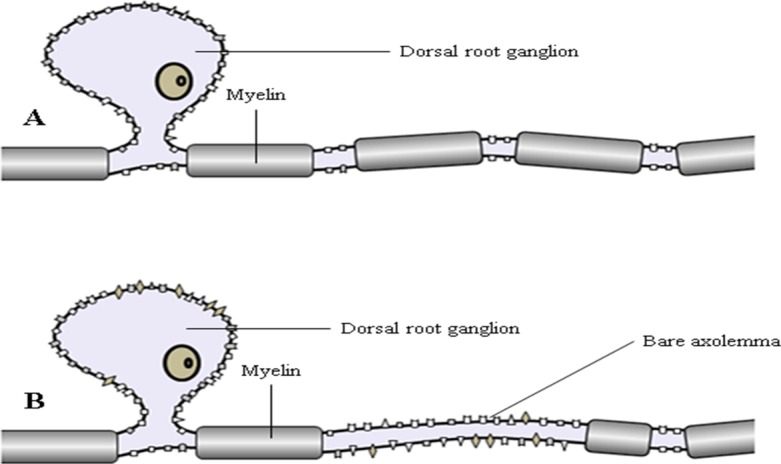

Trauma resulting in injury to ribs (fracture, surgery), or soft tissues lead to bleeding and the release of pro-inflammatory chemicals and immune molecules in the injured area.13 These chemical processes, along with mechanical forces associated with trauma are known to be associated with the removal of myelin from axons.19 It has been shown that myelin can be removed from an axon via mechanical (sudden load, scar tissue), chemical (pro-inflammatory products in bleeding20–22) and disease states directly targetting myelin (multiple sclerosis, human immunodeficiency virus23), thus leaving the axon's outer layer, the axolemma exposed. This exposed axolemma can become a significant source or of persistent pain due to increased ion channel insertion into the exposed axolemma.

Axons send messages electrochemically where the chemicals in and around axons cause electrical impulses. Chemicals in the body are “electrically charged” ions, with the most well-known ones being sodium, potassium, calcium and chloride. Axons contain semi-permeable membranes regulating ion movement, the axolemma.24 The gateway between the “outside” and “inside” of a nerve is an ion channel.19 Ion channels are proteins, clumped together to form a passage for the ions, into or out of the nerve, and inserted throughout the axolemma.19,25 Hundreds of different kind of ion channels exist and can be opened or closed due to changes in voltage, various types of chemicals, temperature changes, presence of immune molecules and mechanical forces. Ion channel expression continually changes in the axolemma.7 It is believed that the average half-life of a typical ion channel is approximately 48 hours, thus allowing for a continued neuroplastic change in the sensitivity of the nervous system.25,26 Ion channel production does have a genetic premise based on DNA coding. Depending on the type of proteins clumped together, different kinds of channels are genetically fabricated.19,25 This inherent genetic coding does ensure some predetermined ion channel expression, but it is believed that the more potent influences on ion channel expression may be from the brain's interpretation of the environment.19 When facing a specific threat, ion channels will be needed for that threat. For example, it is now well established that following a motor vehicle collision (MVC), patients develop immediate hypersensitivity of the nervous system.27,28 Given the high levels of stress and anxiety in and around the MVC, and the uncertainty of the future in regards to recovery, pain and movement, higher numbers of ion channels sensitive to movement may be produced, thus causing a widespread sensitisation of movement of the nervous system after the accident.28–30 This interpretation of increased mechanosensitive ion channels in response to the threat of movement and in the face of high levels of pain may well explain a patient with whiplash associated disorders demonstrating increased sensitivity and decreased movement with neurodynamic tests such as the slump test.31

In areas with significant demyelination, the axolemma will be more accessible to increased numbers of ion channels (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Development of an abnormal impulse generating site. A – axon with myeline intact indicating normal distribution of ion channels in unmyelinated regions in a typical axon. B – increased number of ion channels inserted into the axolemma of an injured axon with demyelination.

In the thoracic spine, demyelination may become a significant issues following rib fractures, thoracic surgery or damage to the costo-transverse or consto-vertebral joints, closely approximated to the intercostal nerves.14,16 It is now well established that when a significant number of ion channels are present in the axolemma, it creates an easier opportunity for the development of an action potential, which is a hallmark sign of peripheral neuropathic pain.19,25 Even though the initial trauma (rib fracture, surgery site or injured joint) has healed, the adjacent nervous system in essence remains extra-sensitive and can discharge electrical impulses much easier with fewer stimuli.25 This unexpected and often disproportionate pain in lieu of the stages of tissue healing can become a major source of pain, anxiety and disability in patients suffering with thoracic injuries. Now, despite tissue healing, patients may report significant post-injury or surgery pain, sensitivity to palpation or pressure, or pain increasing due to changes in temperature or immune events, such as having the flu.15 Not only is this expected and part of the normal biological changes associated with persistent pain, but it also forms a significant cornerstone of therapeutic neuroscience education (TNE).

Posterior Primary Rami Nerves Mimicking Cloward Areas

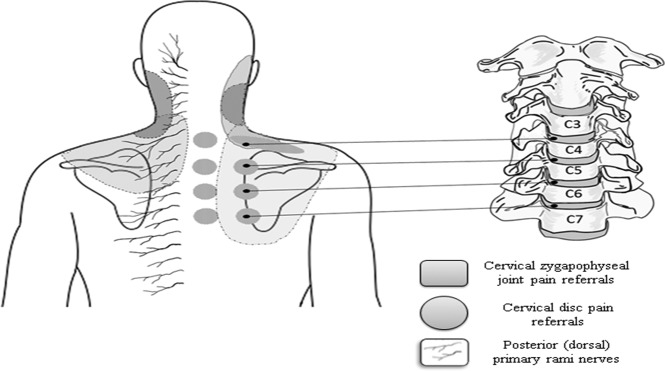

A second common clinical consideration associated with the thoracic spine, is the referral of pain into the thoracic spine originating from the cervical spine. It is now well established that the cervical discs, as well as cervical zygapophyseal joints, are known to refer pain to the upper thoracic spine.32,33 Cervical disc lesions, as an example, are quite common and associated with a MVC.34–36 During the hyperextension phases of a MVC, annulus bruising, annulus tears and the resultant bleeding and inflammation have been well documented.34–36 During the hyperflexion phase of the MVC, injured annulus fibres are often distracted, increasing annular damage and sustaining avulsion from the subchondral bone.34–36 In lieu of the fact that mechanical compression on a healthy nerve is only associated with neurological symptoms (numbness, weakness and paraesthesias),37 a lot of focus has shifted to the inflammatory processes of the injured disc affecting the local neural tissue, especially the dorsal root ganglion (DRG).36,38 With the chemical activation of the DRG, referred pain is often felt in the upper thoracic spine, clinically known as Cloward areas.32,33 Following injection studies on the cervical discs and more recent studies using discography, cervical disc injuries can render the cervical spine rather symptom-free, but produce high levels of “thoracic” pain (Fig. 3).39

Figure 3.

Composite image showcasing the overlap of cervical disc and cervical zygapophyseal pain referral patters over the superficial posterior primary rami nerves.

Additionally, the cervical spine zygapophyseal joints have been shown to be a common source of pain following degenerative changes or trauma, such as a MVC.36,40,41 As with cervical discs, the cervical zygapophyseal joints are known to refer pain in and around the upper thoracic spine (Fig. 3).42,43 For the astute manual therapist, these referral patterns from the cervical discs and zygapophyseal joints should warrant a thorough investigation of the associated joint structures in the cervical spine. From a pain science perspective, though, clinicians are also urged to consider another possible pain pattern which may mimic Cloward and zygapophyseal pain referral: posterior primary rami nerves. Anatomically, the posterior primary rami of the spinal nerves arise in T2 spinal level through T6 spinal level and pursue a right-angle course through the multifidus muscle and local fascia (Fig. 1).44 It is proposed that with sudden hyperflexion of the ribcage during a MVC, the sudden movement and mechanical stretch may cause local demyeliniation, resulting in a bare axolemma. The bare axolemma will in turn allow for an abnormal upregulation of ion channels locally, which may become a major source of persistent thoracic pain (Fig. 2).

This condition, referred to as notalgia paresthetica, is associated with chronic sensory neuropathy with localised itch, pain, paraesthesias and skin sensitivity in the interscapular areas of T2–T6.45 The interesting part is that the point where the posterior primary rami become superficial coincides with both the Cloward areas and the location of the cervical zygapophyseal joint pain referrals.45 It is proposed that local neuropathic pain may indeed become a significant source of persistent local thoracic pain following a MVC.32,46 It is proposed for diagnostic purposes that, for notalgia paresthetica, clinicians consider slump and slump long-sit tests with the cervical spine in lateral flexion and assessing the response of the local thoracic pain to knee flexion.46

Mechanical Properties of the Dura and its Dural Ligament Connections

A third pain science related issue in the thoracic spine spans the domains of pain science, neurodynamics and manual therapy. Neurodynamics is now being conceptualised as any physical dysfunction found on testing which presumes to physically challenge the nervous system.46,47 It can arise from mechanical and/or sensitivity changes in the system, and it is usually associated with changes in other tissues (e.g. musculoskeletal).45,46 Therefore, in neurodynamics, neural tissues may have a tension impairment (a problem handling the mechanical loads imparted on them), be hypersensitive (a problem of pathophysiological changes within them) or a combination of both.48 The main role of the nervous system is electrochemical communication.46 The nervous system needs to perform complex signalling processes, whilst dealing with pressure and pinching from surrounding tissues as it passes through the various anatomical tunnels and compartments to reach its target tissue.46,49–55 It must also deal with demands that it move (lengthen and/or slide) in response to limb and trunk motions.56 Finally, the nervous system must function as the effects of this pressure and movement create blood flow changes (increased/decreased blood flow).46,49,54,55 The nervous system is designed to handle the forces of compression and movement whilst maintaining adequate blood supply. From the anatomical and physiological perspective, the nervous system requires space, movement and blood supply.46,54 If any or all of these three requirements (space, movement and blood supply) are compromised, clinical signs and symptoms may develop.

From a movement perspective, the dura in the thoracic spine may become a significant source of pain.57 The nervous system is a continuous tissue tract (Fig. 4).46 The cranial and spinal dura are continuous and are made up of both elastin and collagen fibres.

Figure 4.

The continuum of the human nervous system.

The ventral dura is thinner than the dorsal dura and it is calculated that the ventral dura contains 7% elastin fibres while the dorsal dura has about twice this amount.58 The elastin content allows the cord and meninges to lengthen and remain functional during an almost 30% increase in spinal canal length from spinal extension to spinal flexion.59 The dura of the upper cervical cord and the posterior cranial fossa are connected and receive innervation from branches of the upper three cervical nerves and, as such, are capable of being one of the causes of cervicogenic headache.43,60–63 The importance of the movement capacity of the dura throughout its course is underscored by whiplash research showing decreased knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion range of motion during slump testing in patients following MVC compared to asymptomatic subjects.31

Anatomically, the dura is anchored to the spinal canal via dural (meningiovertebral) ligaments.5,6,46 Various cadaver studies have shown a much higher concentration of dural ligaments in and around the mid-thoracic spine which authors have referred to as the “anchoring” point of the dura.64,65 Butler46 postulated this anatomical anchoring mechanism to result in the common clinical “pulling” sensation associated with the slump test. This anatomical design would imply that a healthy thoracic spine is needed to allow for optimal movement properties of the highly pain-sensitive dura.57 In fact, two recent studies have tied the physical movement properties of the spinal dura to the development of cervicogenic headaches.66,67 von Piekartz and colleagues68 investigated the difference in cervical flexion and sensory responses (intensity and location) during the Long Sitting Slump test (LSS) in 123 children aged 6–12 years. The test was performed on children with migraine, cervicogenic headache and a control group and it was found that 18% of the headache subjects felt the responses in their head. The results indicated that the intensities of the sensory response rate were highest in the migraine and cervicogenic headache groups compared to the control group. The children with cervicogenic headaches had cervical flexion ranges that differed significantly (P < 0·0001) from both the control group and the migraine headache group. Any mechanical issue that may affect the movement properties of the spinal dura in the thoracic spine there warrants significant consideration and investigation. This includes trauma, surgery, postural changes and growth spurts in kids adding abrupt mechanical load to the pain-sensitive dura.

The physical health of the dura, however, is a very “mechanical” view of pain. It is highly recommended that clinicians consider how chemical activation (inflammation, immune) alongside or, in isolation, may indeed increase sensitisation of the dura, which may become a significant source of persistent pain long after an injury or surgery.57 This is for both local sensitisation and central sensitisation. “Central sensitisation” is defined as a condition in which peripheral noxious inputs into the central nervous system lead to an increased excitability where the response to normal inputs is greatly enhanced.69 Repeated noxious stimuli may cause low-threshold neurons with very large receptive fields to depolarise with innocuous mechanical stimuli.69 Injured neural tissue may actually alter its chemical makeup and reorganise synaptic contacts in the spinal cord such that innocuous inputs are directed to cells that normally only receive noxious inputs.70 The central nervous system becomes “hyperexcitable” due to a combination of increased responsiveness and decreased inhibition.70 This is analogous to the volume being turned up on the system such that normally innocuous stimuli generate painful sensations, and noxious stimuli cause an exaggerated pain response. Central sensitisation has been described as a change in both the software and the hardware of the central nervous system70 such that the cellular depolarisation threshold is reduced.71 Cellular activity continues after peripheral nociception stops and this cellular activity spreads to other neighbouring cells.72 In a patient with thoracic pain due to trauma or surgery, nociceptive specific cells may begin to depolarise with input from primary afferent mechanoreceptors which are normally low-threshold.73 In this case, pain is then perceived in the presence of afferent input that is normally not perceived as noxious (allodynia).74 This upregulation is clinically characterised by disproportionate pain, disproportionate aggravating and easing factors and diffuse palpation tenderness.75

Conclusion

Very little pain-specific physical therapy research is available in regards to the thoracic spine. The aim of this paper was to take well known biological processes in pain science and apply them to clinically reported observations. Research into unique pain issues in the thoracic spine is essential, yet it's refreshing to merge neuroscience with clinical observation, which is much needed in pain science and physical therapy. Even with the lack of scientific evidence, a best-evidence neuroscience treatment can be used in patients suffering from persistent pain in the thoracic spine. For example, emerging pain science research has shown that teaching people more about their pain, from a biological perspective, is not tissue or region specific. In fact, a cornerstone of TNE is to deemphasise local tissue issues, but rather focus on the biological and physiological processes involved in a human pain experience. It is now well established that, during a pain experience, multiple areas of the brain are activated.11,76–78 This finding is contrary to a flawed historic view of a single pain area in the brain.78 This widespread brain activation during a pain experience has become known as the pain neuromatrix, introduced by Ron Melzack in 1996.78 The pain neuromatrix is defined as a pattern of nerve impulses generated by a distributed neural network in the brain.78 Specific to the discussion of chronic pain in the thoracic spine, it is important to know that the pain neuromatrix has been shown to not be tissue (or regional) specific. Common areas, such as the anterior cingulate, hippocampus and amygdala show up on all functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies regardless the tissues involved.11,76–78 All of these would imply that TNE should be, as with low back pain, neck pain, headaches and more, a fundamental part of helping a patient with persistent thoracic spine pain experience less pain and disability.

It is well established that the physical body of a person is represented in the brain by a network of neurons, often referred to as a representation of that particular body part in the brain.79–82 This representation refers to the pattern of activity that is evoked when a particular body part is stimulated. The most famous area of the brain associated with representation is the primary somatosensory cortex (S1).79–82 A main premise behind graded motor imagery (GMI) is a distortion of body maps in the S1. These neuronal representations of body parts are dynamically maintained.6,83–87 It has been shown that patients with chronic pain display different S1 representations than people with no pain.6,83–87 The interesting phenomenon associated with cortical restructuring is the fact that the body maps expand or contract, in essence increasing or decreasing the body map representation in the brain. Furthermore, these changes in shape and size of body maps seem to correlate to increased pain and disability.83,88 Although various factors have been linked to the development of this altered cortical representation of body maps in S1, such as neglect and decreased use of the painful body part,89 it is believed that altered immune activity may be a significant source of the smudging of body maps.5,90 An astounding fact of this reorganisation of body maps is the fact that it occurs fast. It has been shown that when four fingers are webbed together for 30 minutes, cortical maps change associated with the fingers.82 This finding has significant clinical importance as it underscores the importance of strategies such as movement, tactile (hands-on) and visual stimulation of the CNS and brain early in a pain experience to help maintain S1 representation. Given that the S1 map contains a thoracic spine/trunk, it could be argued similar process of altered body maps occur in the patient with thoracic pain who limits his/her movement due to pain.

In line with the introduction, very little research specific to the thoracic spine in regards to chronic pain has been conducted. The discussion of this section focussed on three specific thoracic issues that need clinical consideration. Activation of the pain neuromatrix, as well as reorganisation of the thoracic spine's representation in S1, is biological certainties that mandate treatments for chronic back pain which must include TNE, sensory discrimination, laterality retraining, tactile stimulation, and more.

Disclaimer Statements

Contributors Adriaan Louw and Stephen G. Schmidt contributed to the development of the text Louw – submitted paper Schmidt – artwork for paper.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest Adriaan Louw authored patient books regarding pain education, but is not discussed or part of the paper.

Ethics approval Since this is an invited perspectives paper and not discussing any research project, no ethics approval was required.

References

- 1.Latimer J, Maher C, Refshauge K. The attitudes and beliefs of physiotherapy students to chronic back pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(1):45–50. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moseley GL. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain sciences. Phys Ther Rev. 2007;12:169–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Man Ther. 2003;8(3):130–40. doi: 10.1016/s1356-689x(03)00051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nijs J, Roussel N, Paul van Wilgen C, Koke A, Smeets R. Thinking beyond muscles and joints: therapists' and patients' attitudes and beliefs regarding chronic musculoskeletal pain are key to applying effective treatment. Man Ther. 2013;18(2):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flor H, Braun C, Elbert T, Birbaumer N. Extensive reorganization of primary somatosensory cortex in chronic back pain patients. Neurosci Lett. 1997;224(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maihofner C, Handwerker HO, Neundorfer B, Birklein F. Patterns of cortical reorganization in complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61(12):1707–15. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098939.02752.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moseley GL, Hodges PW, Nicholas MK. A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:324–30. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moseley L. Combined physiotherapy and education is efficacious for chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother. 2002;48(4):297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39(18):1449–57. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(12):2041–56. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery for pathologic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2129–34. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249112.56935.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly AE, Bialocerkowski AE. Does evidence support physiotherapy management of adult complex regional pain syndrome type one? A systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(4):339–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayberry JC, Ham LB, Schipper PH, Ellis TJ, Mullins RJ. Surveyed opinion of American trauma, orthopedic, and thoracic surgeons on rib and sternal fracture repair. J Trauma. 2009;66(3):875–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318190c3d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant R. Physical therapy of the cervical and thoracic spine. 2nd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Therapeutic neuroscience education. Vol. 1. Minneapolis, MN: OPTP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaura H, Hosono N, Mukai Y, Fujii R, Iwasaki M, Yoshikawa H. Persistent local pain after posterior spine surgery for thoracic lesions. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20(3):226–8. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211275.81862.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, Thacker M, Doody C. Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 2 of 3: symptoms and signs of peripheral neuropathic pain in patients with low back ( ± leg) pain. Man Ther. 2012;17(4):345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ. Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet. 1999;353(9168):1959–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devor M.Sodium channels and mechanisms of neuropathic pain J Pain. 200671 Suppl 1):S3–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C, Cavanaugh JM, Ozaktay AC, Kallakuri S, King AI. Effects of phospholipase A2 on lumbar nerve root structure and function. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22(10):1057–64. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franson RC, Saal JS, Saal JA.Human disc phospholipase A2 is inflammatory Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 199217Suppl):S129–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyamoto H, Doita M, Nishida K, Yamamoto T, Sumi M, Kurosaka M. Effects of cyclic mechanical stress on the production of inflammatory agents by nucleus pulposus and anulus fibrosus derived cells in vitro. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(1):4–9. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192682.87267.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louw J, Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Matseke G, McHunu G, Tutshana B. Quality of life among tuberculosis (TB), TB retreatment and/or TB-HIV co-infected primary public health care patients in three districts in South Africa. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):77. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker RA, Barasi S. Neuroscience at a glance. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devor M. Response of nerves to injury in relation to neuropathic pain. In: McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, editors. Melzack and wall's textbook of pain. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devor M, Govrin-Lippmann R, Angelides K. Na+ channel immunolocalization in peripheral mammalian axons and changes following nerve injury and neuroma formation. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1976–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-01976.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jull G, Sterling M, Kenardy J, Beller E.Does the presence of sensory hypersensitivity influence outcomes of physical rehabilitation for chronic whiplash? A preliminary RCT Pain. 20071291–2):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J. Sensory hypersensitivity occurs soon after whiplash injury and is associated with poor recovery. Pain. 2003;104(3):509–17. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R.Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury Pain. 20051141–2):141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterling M, Kenardy J. Physical and psychological aspects of whiplash. Important considerations for primary care assessment. Man Ther. 2008;13:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeung E, Jones M, Hall B. The response to the slump test in a group of female whiplash patients. Aust J Physiother. 1997;43(4):245–52. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grubb SA, Kelly CK. Cervical discography: clinical implications from 12 years of experience. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(11):1382–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cloward RB. Cervical discography. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1963;1:675–88. doi: 10.1177/028418516300100319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demircan MN, Asir A, Cetinkal A, Gedik N, Kutlay AM, Colak A et al. Is there any relationship between proinflammatory mediator levels in disc material and myelopathy with cervical disc herniation and spondylosis? A non-randomized, prospective clinical study. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(7):983–6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0374-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Acute injuries to cervical joints. An autopsy study of neck sprain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18(9):1115–22. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Disc injuries in cervical trauma. Lancet. 1990;336(8726):1318. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rempel DM, Diao E. Entrapment neuropathies: pathophysiology and pathogenesis. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2004;14(1):71–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott JE, Bosworth TR, Cribb AM, Taylor JR.The chemical morphology of age-related changes in human intervertebral disc glycosaminoglycans from cervical, thoracic and lumbar nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus J Anat. 1994184Pt 1):73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka Y, Kokubun S, Sato T, Ozawa H. Cervical roots as origin of pain in the neck or scapular regions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(17):E568–73. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000229261.02816.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogduk N. The neck and headaches. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(1):151–171. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8619(03)00100-2. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogduk N. Whiplash can have lesions. Pain Res Manag. 2006;11(3):155. doi: 10.1155/2006/861418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper G, Bailey B, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):344–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bogduk N. Role of anesthesiologic blockade in headache management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2004;8(5):399–403. doi: 10.1007/s11916-996-0014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vallières E. The costovertebral angle. Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 2007;17(4):503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, Meynadier J. Notalgia paraesthetica: clincial, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:215–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Butler DS. The sensitive nervous system. Adelaide: Noigroup Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shacklock M. Clinical neurodynamics. London: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shacklock MO.Clinical application of neurodynamics Shacklock MO.Moving in on pain Australia: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995; p. 123–31. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breig A. Adverse mechanical tension in the central nervous system. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breig A. Biomechanics of the central nervous system. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breig A, El-Nadi FA. Biomechanics of the cervical spinal cord. Acta Radiol. 1966;4:602–24. doi: 10.1177/028418516600400602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breig A, Marions O. Biomechanics of the lumbosacral nerve roots. Acta Radiol. 1963;1:1141–60. doi: 10.1177/028418516300100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Breig A, Troup J. Biomechanical considerations in the straight leg raising test. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1979;4(3):242–50. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197905000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butler DS. Mobilization of the nervous system. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shacklock M. Clinical neurodynamics: a new system of neuromusculoskeletal treatment. Sydney: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coppieters MW, Butler DS. Do ‘sliders’ slide and ‘tensioners’ tension? An analysis of neurodynamic techniques and considerations regarding their application. Man Ther. 2007;13(3):213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Louw A, Mintken P, Puentedura L.Neuophysiologic effects of neural mobilization maneuvers Fernandez-De_Las_Penas C, Arendt-Nielsen L, Gerwin RD.Tension-type and cervicogenic headache Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2009; p. 231–45. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakagawa H, Mikawa Y, Watanabe R. Elastin in the human posterior longitudinal ligament and spinal dura. A histologic and biochemical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19(19):2164–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Troup JD. Biomechanics of the lumbar spinal canal. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1986;1:31–43. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(86)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu JW, Vernon H, Tatourian I. Changes in neck electromyography associated with meningeal noxious stimulation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(9):577–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turnbull DK, Shepherd DB. Post-dural puncture headache: pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91(5):718–29. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malick A, Burstein R.Peripheral and central sensitization during migraine Funct Neurol. 200015Suppl 3):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moskowitz MA.Neurogenic inflammation in the pathophysiology and treatment of migraine Neurology. 1993436 Suppl 3):S16–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scapinelli R. Anatomical and radiologic studies an the lumbosacral meningovertebral ligaments of humans. J Spinal Disord. 1990;3:6–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Savolaine ER, Pandja JB, Greenblatt SH, Conover SR. Anatomy of the lumbar epidural space: new insights using CT-epidurography. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:217–23. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198802000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jull G, Trott P, Potter H, Zito G, Niere K, Shirley D et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(17):1835–1843. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209010-00004. [discussion 1843] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zito G, Jull G, Story I. Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual Ther. 2006;11(2):118–29. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Piekartz HJ, Schouten S, Aufdemkampe G. Neurodynamic responses in children with migraine or cervicogenic headache versus a control group. A comparative study. Man Ther. 2007;12(2):153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: uncovering the relation between pain and plasticity. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(4):864–7. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264769.87038.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woolf CJ. Pain. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7(5):504–10. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shevel E, Spierings EH. Cervical muscles in the pathogenesis of migraine headache. J Headache Pain. 2004;5(1):12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000;288(5472):1765–9. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Woolf CJ, Shortland P, Sivilotti LG. Sensitization of high mechanothreshold superficial dorsal horn and flexor motor neurones following chemosensitive primary afferent activation. Pain. 1994;58(2):141–155. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90195-3. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wall PD, Melzack R. Textbook of pain. 5th edn. London: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, Thacker M, Doody C. Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 1 of 3: symptoms and signs of central sensitisation in patients with low back ( ± leg) pain. Man Ther. 2012;17(4):336–44. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flor H. The image of pain. Paper presented at: Annual Scientific Meeting of The Pain Society (Britain); 2003; Glasgow, Scotland.

- 77.Flor H. The functional organization of the brain in chronic pain. Prog Brain Res. 2000;129:313–22. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)29023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Melzack R. Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1378–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wand BM, Parkitny L, O'Connell NE, Luomajoki H, McAuley JH, Thacker M et al. Cortical changes in chronic low back pain: current state of the art and implications for clinical practice. Man Ther. 2011;16(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Penfield W, Boldrey E. Somatic, motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain. 1937;60:389–448. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Flor H. The functional organization of the brain in chronic pain. In: Bromm B, Gebhart GF, editors. Progress in brain research. Vol. 129. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stavrinou ML, Della Penna S, Pizzella V, Torquati K, Cianflone F, Franciotti R et al. Temporal dynamics of plastic changes in human primary somatosensory cortex after finger webbing. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(9):2134–42. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Flor H, Braun C, Elbert T, Birmbaumer N. Extensive reorganisation of primary somatosensory cortex in chronic back pain patients. Neurosci Lett. 1997;244:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moseley GL. I can't find it! Distorted body image and tactile dysfunction in patients with chronic back pain. Pain. 2008;140(1):239–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lotze M, Moseley GL. Role of distorted body image in pain. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9(6):488–96. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moseley GL. Distorted body image in complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology. 2005;65(5):773. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000174515.07205.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Flor H, Elbert T, Muhnickel W, Pantev C. Cortical reorganisation and phantom phenomena in congenital and traumatic upper-extremity amputees. Exp Brain Res. 1998;119:205–12. doi: 10.1007/s002210050334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lloyd D, Findlay G, Roberts N, Nurmikko T. Differences in low back pain behavior are reflected in the cerebral response to tactile stimulation of the lower back. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(12):1372–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181734a8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marinus J, Moseley GL, Birklein F, Baron R, Maihöfner C, Kingery WS et al. Clinical features and pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(7):637–48. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70106-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beggs S, Liu XJ, Kwan C, Salter MW. Peripheral nerve injury and TRPV1-expressing primary afferent C-fibers cause opening of the blood-brain barrier. Mol Pain. 2010;6:74. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]