Abstract

Adrenal lymphangiectatic cyst is a very rare pathological and clinical disease entity, and its clinical silence and lack of characteristic symptoms and signs makes it difficult to diagnose preoperatively. We experienced a case of adrenal lymphangiectatic cyst, accompanied by severe refractory hypertension, which was corrected by surgical removal of the cyst.

We reprot it with a review of the literature.

Keywords: Adrenal lymphangiectatic cyst, Refractory hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Adrenal cyst thus a rare disease entity, lacks common clinical features, making it difficult to diagnose preoperatively, especially before the introduction of modern radiological devices, computerized tomograms and sonograms.

Although several hundred cases have been repoted in world literature, the majority of them were discovered upon autopsy or as incidental findings at operation for other disease, the remainder of the cases were diagnosed after surgery due to gastrointestinal or renal symptoms caused by pressure or displacement of the adjacent organs by the cyst’s large size.

There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the etiology and pathogenesis of adrenal cysts. Furthermore, in order to classify it a wide variety of descriptive terms has been introduced to denote the same or different types of adrenal cysts.

Abeshous2) proposed the following simple and inclusive classification: 1) parasitic cysts, 2) congenital glandular cysts, 3) cystic adenoma, 4) endothelial cysts, and 5) pseudocysts.

The pseudocysts were further subdivided into 1) hemorrhagic cysts originating in hematoma and 2) hemorrhagic cysts originating in benign or malignant tumors.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital because of severe hypertension. She had been relatively well until several weeks previous, when she suffered from a headache coupled with palpitations and facial flushing.

On admission, her blood pressure was 240/140 mmHg, pulse 89, and temperature 37.2°C. She was known to have mild hypertension, which had not been monitored and treated regularly. There was no history of pulmonary disease, diabtes, fever, or arthralgia, and she did not take alcohol, anorexigenic agents, or contraceptives.

On examination, the patient was plethoric, agitated, and obese. No rash or lymphadenopathy was found. The pupils were of equal size and reactive. The retinal arterioles were narrowed on fundoscopy.

Her neck was supple and the thyroid gland was not enlarged. The lung sound was clear and no heart murmur was audible. On the abdomen, no mass was palpated and no bruit was heard, and the abdomen was not rigid. Extremity examination was negative.

On laboratory evaluation, the complete blood count, urinalysis, and liver function test were within normal limits. The electrolyte counts were sodium 142 mEq/L, potassium 2.55 mEq/L, chloride 103 mEq/L, and total calcium 8.8 mg%. Triglyceride was 186 mg%, and the total lipid was 490 mg%. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine were 14.2 mg/dl and 0.9 mg/dl, respectively.

The patient was given a large dose of antihypertensive medication (cateolol 5 mg per orally bid, prazocin 8 mg per orally bid, and nifedipine 10 mg per orally bid), but her blood pressure was refractory to these medications. In order to exclude secondary hypertension, a hormonal assay was begun and an abdominal sonogram taken. The sonogram revealed a slightly irregular tabulated low echogenic mass in the left adrenal fossa, and there was no calcification and no posterior enhancement.

The distance between the mass and the left kidney was remote without colse attachment. An intravenous pyelogram and barium enema showed normal findings. Plasma cortisol was suppressed by dexamethasone 1 mg to below 1.0 ug/dl. Serum ACTH was 19.8 pg/ml, ketosteroid 3.8 ng/day, and 17 OHCS 2.45 ng/day. Serum aldosterone (at supine) was 4.4 ng/dl, and plasma cortisol was 13.0 ug/dl. Plasma renin activity was within the normal limit, but urine VMA and metanephrine was elevated above the upper normal limit, 12.0 mg/day and 1.4 mg/day, respectively.

A computerized tomogram of the abdomen showed a well-defined non-enhancing low-density oval-shaped mass in the left adrenal gland. It measured about 2.8 cm in diameter (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An abdomen-enhanced CT scan shows a well-defined, non-enhancing, oval-shaped, low-density mass with a thin wall at the left suprarenal area.

The patient was transferred to the Department of surgery and underwent a laparotomy on the 14th hospital day under the impression of cystic pheochromocytoma.

Through a left flank incision, the retroperitoneum was exposed, and a child fist-sized (4×5×4 cm) brown-gold colored adrenal tumor was noted. The tumor was removed while preserving the ipsilateral kidney. During manupulation of the tumor, the blood pressure rapidly increased to 260/150, so nitroprusside was infused to control it.

Grossly, the adrenal gland was cystic in nature with a smooth outer surface that measured 5×4×3 cm and weighed 23.5 grams. The cut surface showed a large cyst, which had mainly replaced the adrenal gland. The cyst contained clear fluid. A portion of the remaining adrenal tissue contained serous fluid with various sized numerous cysts.

Microscopically, the adrenal gland had been mainly replaced by a large cyst. This large cyst was located at the medullary portion, and its wall was composed of loose fibrous tissue with focal calcification. This remaining adrenal proper tissue showed numerous small cysts of various sizes and shapes.

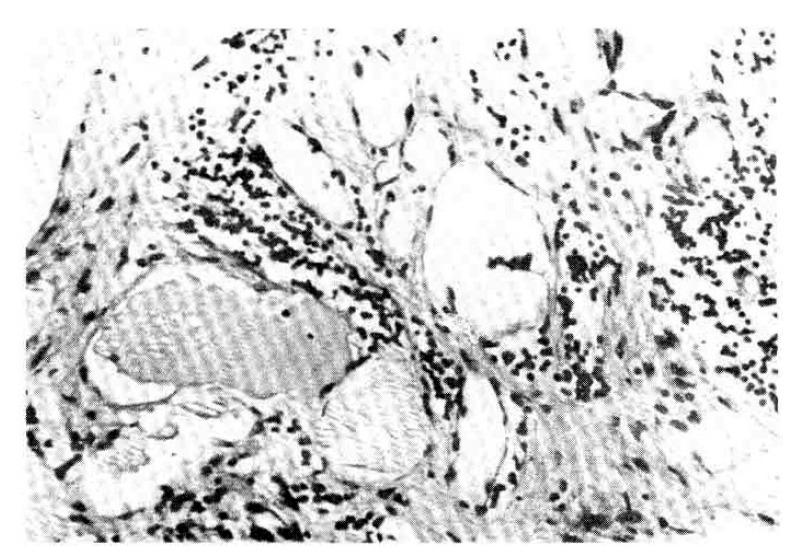

These small remaining cysts were lined with flattened single endothelial cells and contained pale eosinophilic fluid with a few lymphocytes. Adjacent adrenal tissue showed scattered infiltrates of lymphocytes. Calcification was also present. These cysts originated from an ectatic change of the lymphatic vessels(Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The cysts are lined by flattened endothelial cells and contain pale eosinophilic fluid with lymphocytes in the lumens. Scattered infiltrates of lymphocytes in the stroma are present (H-E stain, × 400).

Just after the operation and in the recovery room, the patient’s blood pressure dropped sharply to 60/40 without nitroprusside, and dopamine was infused until the next day to increase the blood pressure.

From the 3rd postoperative day, her blood pressure was stabilized without medication, and urine catecholamine metabolites checked on the 7th postoperative day were reported to be within the normal limit. The VMA was 2.4 mg/day, and metanephrine was 1.1 mg/day.

After her discharge and throughout the follow-up period until 14 months later, the patient remained normotensive with intermittent minimal doses of antihypertensive medication and was reported free of previous symptoms.

COMMENTS

Lymphangiectatic cyst is the most common type of adrenal cyst1), but there is no general agreement regarding the exact pathogenesis of this adrenal lesion.

Some authors2) attribute this variety of cyst formation to an ectasia of the lymphatic vessels, normally present in the capsule and medulla but absent in the cortex. Consequently, it is possible that faulty development or incomplete linkage of these minute lymph spaces with larger lymphatic channels may lead to the development of multiple lobules or cystic areas but rarely to the formation of a large lymphangiomatous cyst.

Others3–5) suggest that is the end result of a cystic regeneration of hamartoma, though unlike a pseudocyst, which is caused by absorbed hamartoma in the normal or pathological adrenal gland.

The lymphangiectatic cyst, occasionally referred to as cystic lymphangioma, could be regarded as a true benign tumor-like overgrowth of the adrenal cells.

From a pathological view point, the distinguishing features between the two most common types of cyst, the lymphangiectatic and hemorrhagic pseudocyst, appear to be6): 1) a layer of flattened endothelium which usually lines the former but is absent in the latter. 2) the contents, if clear, give no help, which may be milky if of lymphatic origin or bloody or reddish-brown if of hemorrhagic origin, and 3) lymphangiomatous cysts, which are commonly multilocular with many loculi separated by thin septa of fibrous tissue and until pseudocysts, which are usually unilocular and frequently have blood clots or deposits of fibrin on the wall.

However, in spite of these criteria, it may be impossible in any given case to differentiate between the two, because, as we mentioned earlier, most adrenal cysts are small, asymptomatic, and lacking characteristic signs and symptoms.

So the most important clinical problem is still finding out how this cyst attains its large size to produce pressural symptoms. However, some cases have been reported regarding adrenal cortical hypertension, Cushing syndrome, or virilism. Geelhead7) and Budd DC8) presented two cases of adrenal cyst with refractory hypertension which was corrected by surgical removal of the cyst, but they could not verify the endocrine dysfunctions biochemically.

Likewise, in our case, we think it is noteworthy that we diagnosed an adrenal lymphangiectatic cyst while in search of an endocrine dysfunction as the cause of hypertension9).

Our patient’s severe hypertension was normalized through the surgical removal of the adrenal cyst, while the catecholamine metabolites, which had increased before surgery, became normal.

Although an adrenal vascular study was not performed in our case, we believe that the size of the cyst was not large enough to compromise the renal blood flow, considering the fact that catecholamine levels are not measurably higher in patients with unilateral renovascular hypertension.

We suggest that the overproduction of catecholamine, caused by an adrenal medullary lymphangiectatic cyst, played an important role and may not have been the sole cause in the elevation of blood pressure in our patient.

In conclusion, whatever mechanism activates the sympathochromaffin system, we think that the adrenal medullary lymphangiectatic cyst could be regarded as a functioning tumor in some cases rather than a simple space-occupying lesion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lynn RB. Cystic lymphangioma of the adrenal associated with arterial hypertension. Can J Sur. 1965;8:92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeshous GA, Goldstein RB, Abesous BS. Adrenal cysts: Review of the literature and report of three cases. Urol. 1959;81:711. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)66099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis FM, Dawe CH, Ciagett OT. Cysts of the adenal glands. Ann Surg. 1952;136:217. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195208000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barron SM, Emanuel B. Adrenal cyst: A case report and a review of the pediatric literature. J Pediat. 1962;59:592. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(61)80244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon SK, et al. Cystic hamartoma of the adrenal gland: A cases report. Boston Med Quart. 1960;11:85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connell ND. Adrenal cysts: Brit J Radiol. 1959;32:190. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-32-379-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glenn W, Geelhead, Charklia T, Spiegel MD. Incidental adrenal cyst: A corrctable lesion possibly associated with hypertension. Sout M J. 1981;74:624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budd DC, Fink DL. Adrenal cyst associated with hypertiension. Abdominal Surgery. 1979;21:58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidmann P, Schiffl H, Ziegler WH, Glick Z, Meier A, Keush G. Catecholamines, sodium and renin in unilateral renal hypertension in man. Mineral Electrolyte Metab. 1982;7:97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]