Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the prakṛti of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients and its association with IBS subtypes and quality-of-life (QOL).

Methodology:

IBS patients with the consistent subtype in the last 6 months were recruited. Prakṛti assessment with a 24-item questionnaire was performed and depending on the scores the patients were categorized into vāta predominant, pitta predominant, and kapha predominant prakṛti. QOL was assessed with prevalidated disease-specific 34-item questionnaire scored on a 0–100 scale.

Results:

Of 50 IBS patients enrolled, with mean age of 43.5 ± 12.8 years, and male: female as 43:7, 22 patients were of vāta and pitta predominant prakṛti each while six patients had kapha predominant prakṛti. IBS-C was diagnosed in 24 patients, IBS-D in 21, and IBS-M in five patients. In vāta predominant group, IBS-C was found in 13 patients, IBS-D in 8, and IBS-M in 1. In pitta predominant group, IBS-D was found in 13, IBS-C in 6, and IBS-M in 3. In kapha predominant group, IBS-C was found in 5 patients and IBS-M in 1. The median QOL in IBS-C group was 48.897, IBS-D was 38.97, and IBS-M was 66.911. The median QOL score 52.205, 42.27, and 55.51 in vāta, pitta, and kapha predominant group, respectively.

Conclusion:

Majority of the vāta predominant patients had developed IBS-C, pitta predominant patients had developed IBS-D. QOL was better in pitta predominant individuals of all IBS-disease subtypes. With this, we find that prakṛti examination in IBS helps in detecting the proneness of developing an IBS subtype and predicting their QOL accordingly.

KEYWORDS: Ayurveda, disease proneness, doṣa predominance, irritable bowel syndrome, prakṛti, quality-of-life

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by chronic abdominal pain, discomfort, bloating, and alteration of bowel habits. It is a functional gastrointestinal disorder with no known organic cause. Apart from the above symptoms, the patient may suffer from dyspepsia, increased flatulence and belching, heartburn, nausea and vomiting. Diagnosis of IBS is by “exclusion” and there is no concrete treatment as such. The diagnosis of IBS can be made using the ROME criteria.[1] The prevalence of IBS is increasing in countries in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in developing countries. In India, the prevalence of IBS is between 4.2% and 7.9% with male dominance and it is also more common in the young population.[2] IBS adversely influences psychological behavior and quality-of-life (QOL) of the patient. Depending on the predominant symptom, presentation IBS can be classified into subtypes such as IBS-D (IBS with diarrhea), IBS-C (IBS with constipation), and IBS-M (mixed symptoms).

As there is no pathology in the gut that can be targeted by therapeutic agents, the treatment of the disease is symptomatic at best. Hence, a complete cure for IBS cannot be achieved. In view of this, we felt a need to investigate this disease according to the principles of Ayurveda.

Ayurvedic tradition lays emphasis on individual variations in health and disease as its basic principle. In addition to this, the tradition prescribes ten aspects of the investigation of a patient (daśavidha rugṇa parīkṣā). One may find more details in the vimanasthāna of Caraka samhitā.[3] One of the basic principles of Ayurveda is that prakṛti is of an individual is determined at the time of conception and remains constant throughout life.[4]

Vāta, pitta, and kapha play a vital role in the prakṛti formation. Along with them several other factors take part in determination of prakṛti such as śukra (male genetic prototype), śoṇita (female genetic prototype), mātuḥ-āhāra-vihāra (diet and lifestyle of mother), garbhāśayaṛtuṣu (uterine environment).[3]

According to Ayurveda, an individual's basic constitution to a large extent determines his predisposition to diseases. This basic constitution, prakṛti gives vital insights into the prognosis of any disease, the appropriate therapy, and also the lifestyle, which is best suited for him.

Prakṛti of an individual has been classified into ekala (n = 3, vātala, pittala, kaphala), dvidoṣaja (n = 6 mixed characters of two doṣas), and sama-dhātu-prakṛti (n = 1, all three doṣas in equilibrium). Among the above, the first three are considered as extremes, exhibiting readily recognizable phenotypes, and are more predisposed to specific diseases. Precise determination of prakṛti of an individual is crucial to any Ayurvedic intervention.

Studies show that prakṛti can be linked with the genetic makeup of an individual,[5] in addition to this, there are studies, which put forward association of prakṛti and conventional disease. A positive correlation between vāta prakṛti and Parkinsonism was demonstrated in one such study.[6] Understanding IBS and prakṛti may give clues for future treatment and better management for IBS patients resulting in better QOL. As our first step in investigating the link between prakṛti and IBS, we collected data by an observational pilot study about IBS using Ayurveda parameters, mainly prakṛti. Thus, a pilot study was planned with an objective of detecting associations between different types of prakṛti and subtypes of IBS. It was also decided to compare the QOL of patients with different prakṛtis in each disease subgroup.

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles laid down by Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants (ICMR guidelines 2006) and Declaration of Helsinki (2010). After obtaining Institutional Ethics Committee permission, patients attending the gastroenterology outpatient departments (OPD), prediagnosed as IBS were administered the informed consent document. Those fulfilling the selection criteria and providing written informed consent were recruited in the study. The selection criteria were patients of either sex aged 18–60 years, having signs and symptoms of IBS for past 1 year, and consistent with one particular subtype of IBS for last 6 months.

Being a pilot study conducted in a specialty OPD, the sample size was decided as 50. This was based upon the approximate patient count of the OPD and the anticipated recruitment rate. The subjects recruited in the study were requested to submit their medical records of the OPD for review and to decide the disease subtype.

Following this, they were asked a series of questions and were examined by a qualified Ayurveda physician to evaluate their physical (10 items), physiological (9 items), and psychological characteristics (5 items) using a “24-item questionnaire” that has been used earlier in studies.[7,8] Each characteristic was categorized into vāta, pitta, and kapha doṣa. Thus, for each item one of the three doṣas was marked and given a score of 1. At the end, the scores were added for individual doṣas and the doṣa which had the highest score was considered as predominant, second highest was considered as anubandha doṣa, and the prakṛti of the patient was labeled after that doṣa. Thus, the patients were categorized into vāta predominant, pitta predominant, and kapha predominant prakṛtis.

Prakṛti is decided by physical, physiological, and psychological characteristics. One and/or all characteristics may differ from normal healthy status in a diseased person. In the present study, a qualified and experienced Ayurveda physician investigated all patients for prakṛti. Furthermore, to minimize inter-observer error we decided to have a single Ayurveda physician throughout the study. It is very difficult to make an objective scale to determine such parameters. It is rather a skill developed over the regular clinical practice, which helps a physician to come to a conclusion in a short time about an individual's prakṛti and vikṛti. Experience and semi-objective points from the prakṛti score chart collaboratively can lead to determine prakṛti to the nearest accurate type.

IBS-QOL,[9] a prevalidated disease-specific questionnaire, was selected as an instrument for measuring the QOL of IBS patients. This had 34 items, each with a five-point response scale. The responses to the 34 items were summed and averaged for a total score and then transformed to a 0–100 scale for ease of interpretation. Lower scores indicated better IBS specific QOL.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was used to illustrate the demographic data, prakṛti of the patients, and type of IBS. QOL scores were expressed as median (as data were skewed) and 25th–75th interquartile range.

RESULTS

Of the 50 selected patients of IBS, 43 were males, and 7 were females. The mean age of these study participants was 43.5 ± 12.8 years. On prakṛti examination, no individual was found with ekala or sama-prakṛti, all enrolled patients had dvidoṣaja prakṛti. Of the 50 IBS patients, vāta and pitta predominant prakṛti were found in 22 patients each while only 6 patients had kapha predominant prakṛti.

IBS-C was diagnosed in 24 patients, IBS-D was diagnosed in 21 patients, and 5 patients presented with mixed symptoms as IBS-M.

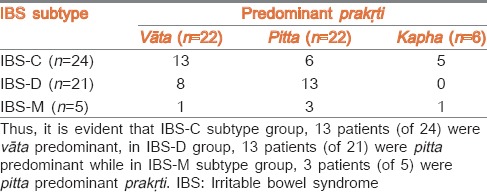

When data were further analyzed taking into consideration the predominant prakṛti of the patient and IBS subtypes, it was found that in vāta predominant group (n = 22), 13 were of IBS-C type, 8 were of IBS-D type, and only 1 patient had IBS-M type. Similarly, in pitta predominant group (n = 22), 13 were of IBS-D type, 6 were of IBS-C type, and 3 patient had IBS-M type. In kapha predominant group (n = 6), 5 were of IBS-C type and only 1 patient had IBS-M type [Table 1].

Table 1.

Prakṛti wise distribution of patients in IBS-C, D, and M

Thus, it is evident that in IBS-C subtype group, 13 patients (of 24) were vāta predominant, in IBS-D group, 13 patients (of 21) were pitta predominant while in IBS-M subtype group, 3 patients (of 5) were pitta predominant prakṛti.

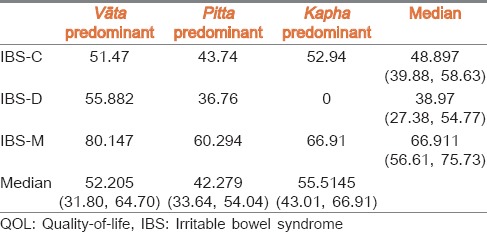

Similarly, QOL score was calculated in all the patients. The median QOL in IBS-C group was 48.897, IBS-D was 38.97, and IBS-M was 66.911 according to disease subtype. These scores when categorized according to prakṛti predominance, the median QOL score of vāta predominant group was 52.205, of pitta predominant group was 42.279, and of kapha predominant group was 55.5145. (P > V > K) Thus, QOL was worst in kapha predominant individuals, followed by QOL being a little better in vāta predominant individuals, and QOL being best among pitta predominant individuals having IBS disease. Pitta predominant individuals, irrespective of the type of IBS they may suffer, live a better QOL than the other prakṛti dominant individuals in a given IBS disease subtype. The median QOL scores according to prakṛti and IBS subtype is depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

QOL scores of IBS patients according to prakṛti predominance

DISCUSSION

In our study, 50 enrolled IBS patients IBS-C was 24 (48%), IBS-D was 21 (42%), and IBS-M was 5 (10%). Similar pattern of patient distribution was found in a study conducted in Iran in 2009 by using the ROME III criteria. Constipation was predominant in 52% of IBS cases, diarrhea was predominant in 18% cases, and 8% experienced mixed type in IBS.[10] This reflects the incidence of IBS-C to be more common than other disease subtypes. Over the course of treatment, the IBS subtype may change for a given patient hence we had included only those individuals with the same type of IBS for at least 6 months before they enrolled for the study.

On prakṛti examination, we found all patients to have dvidoṣaja prakṛti. Ayurveda explains that dvidoṣaja prakṛti and ekala prakṛti people are more susceptible to diseases as compared to sama-dhātu-prakṛti (all three doṣas in equilibrium). Dvidoṣaja prakṛtis are further subgrouped according to predominant (pradhāna) and sub-dominant (anubandha) doṣa. In the present study, we considered only the predominant doṣa while relating with IBS subtype and QOL scores.

In the present study, we found that 88% patients were vāta and pitta predominant (each 44%) but only 12% were kapha predominant. Considering symptomatology of IBS, duṣṭi of agni is a remarkable feature with the involvement of annavāha and majjāvāha srotases primarily. Hunger, thirst, and bowel habits are irregular in vāta predominant person. Thus, the habit of food and water consumption is not so healthy in terms of time and quantity. Thus, vāta predominant persons may be prone to decreased GI motility, decreased GI secretory activity, indigestion, and constipation. Krūra-koṣṭha is commonly seen in vāta predominant persons. Thus, in our study also we found that in the vāta predominant patients 13 (of 24) had IBS-C variety. Another possible explanation will be rūkṣa-guṇa of vāta may lead to constipation, and this depends on the type of food too.

Pitta predominant persons have excessive hunger and thirst. They have increased GI motility and increased secretory functions, diarrhea. Mṛdu koṣtḥa is commonly seen in pitta predominant persons. Thus, in our study also we found that pitta predominant patients nearly 13 (of 21) has IBS-D variety. Drava and uṣṇa guṇa of pitta may be a cause of IBS-D and M in pitta predominant persons.

For the current study, data were collected from the densely populated urban area (Mumbai). Unhealthy lifestyle (diet, stress, physical exertion, etc.) and environmental factors may adversely affect to produce agni-duṣṭi. Vāta and pitta predominant individuals may be more prone to these adverse changes than kapha predominant ones. Stressful life also affects majjāvaha srotas and may give rise to depression related psychological triggers and diseased conditions. It is a well-established fact that IBS is aggravated during such psychological conditions. Environmental factors do not affect the kapha predominant individuals to a great extent. This may be an explanation as to why lesser number of kapha predominant patients enrolled in our study as they may be less susceptible to develop IBS.

Though IBS is not at all a life-threatening condition but QOL is hampered because of it. QOL scores were better with pitta predominant patients irrespective of the type of IBS they developed. Even when pitta predominant patients developed IBS-M, which has generally poor QOL, their QOL score (66.911) was less than vāta predominant or kapha predominant individuals with IBS-M reflecting a better QOL. Similarly, pitta predominant patients developing IBS-C or D had better QOL than their counterparts who had vāta predominant or kapha predominant and with IBS-C or D. Better QOL in pitta predominant patients could be attributed to better digestive power and good response to drug treatment. Further, in the vāta predominant group, QOL of those with IBS-C is marginally better than those with IBS-D. In kapha predominant group, QOL of IBS-C is average. QOL irrespective of prakṛti was worst in IBS-M type [Table 2]. This may be because after attaining disease status, prakṛti may not have a major role to play in disease pathology.

This study underlines the need of understanding basic Ayurvedic diagnosis in which each personality is distinguished at a subtler level than in conventional diagnosis. By understanding prakṛti, one may try to prevent the incidence of a disease by avoiding known contributory factors and also manage the patient better knowing his/her inherent strengths and weakness to tackle the disease. Recent research has also put forward the fact that identifying the prakṛti may be of great help in predicting proneness to a disease and individualizing therapy.[11] Shilpa and Venkatesha Murthy also postulated that it should be possible to group people based on their physical characteristics and be able to predict their psychological manifestations. This classification will also give us an opportunity to correlate the type/strata/group of people to (i) understand proneness of disease development, (ii) delineating the risks and subsequently (iii) take measures to avoid or cure the disease.[12] Many researchers in the past have shown the relation of prakṛti to a specific disease or pathology in the body. They have detected strong relation with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and inflammatory conditions with prakṛti. Claims have been made that vāta-kapha and kaphaja prakṛti individuals are at risk and prone to develop these chronic diseases.[13] Another study done by Venkataraghavan et al. showed that in cancer patients, pitta prakṛti was found predominantly followed by kapha prakṛti.[14,15] Prakṛti need not only be considered as an indicator for proneness to disease but also can be used as a prognostic predictor of how well the individual will respond to treatment.[14]

Thus, not only the disease and prakṛti are related but pheno-genotype correlations are also made with prakṛti. In this context, Ayurgenomics a new, unique concept is gaining interest. A study done by Juyal et al. suggested discrete causal pathways for RA etiology in prakṛti based subgroups, thereby validating concepts of prakṛti, and personalized medicine in Ayurveda.[15] A unique study done by Council of Scientific and Industrial Research showed most contrasting prakṛti types exhibited differences in liver function tests, lipid profiles, and hematological parameters like hemoglobin levels. Differential gene expression was found in a significant number of housekeeping and disease-related genes. A significant variation in expression of genes related to metabolism, transport, immune response, and regulation of blood coagulation was also observed.[16] Scientists have observed correlations between CYP2C19 genotypes of individuals who are either fast and slow metabolizers of drugs and endogenous substances and prakṛti. These observations are likely to have a significant impact on the phenotype-genotype correlation, drug discovery, pharmacogenomics, and personalized medicine.[17] Aggarwal et al. have shown through genetic analysis, that two contrasting constitutions within nondiseased normal persons derived from the same genetic background differ both at the expression and genetic level with respect to the EGLN1 gene and these differences are linked to high-altitude adaptation and susceptibility to HAPE.[18]

Thus, the prakṛti correlation has been done for many diseases and prakṛti considerations emerge as predictors of disease development and response to treatment. In our study of IBS and prakṛti, it can be concluded that vāta predominant are more prone to develop IBS-C and pitta predominant are more prone to develop IBS-D. We have also correlated prakṛti with QOL of IBS patients and it can be postulated that pitta predominant patients will have better QOL reflecting good response to treatment while vāta predominant and kapha predominant if presenting with IBS may have satisfactory to fair QOL and may need aggressive management and therefore, the treating physician may plan accordingly rather than labeling patients as nonresponsive to therapy.

Thus, perspectives of looking at a health problem may be different in allopathic and Ayurveda but integrating both allopathic and Ayurveda approaches will go a long way in providing a complete cure for a diseased condition. To bridge the gap between conventional medicine and Ayurveda such studies are required. Though the sample size of the present study is small and involves a tertiary care hospital there is scope for future long-term studies.

CONCLUSION

Prakṛti considerations can predict susceptibility to acquire/develop a particular disease. In our study, majority of the vāta predominant patients had developed IBS-C while pitta predominant had developed IBS-D. In addition, QOL was better in pitta predominant individuals of any IBS disease subtype. Thus, prakṛti examination in IBS may not only help in detecting the proneness of developing a given IBS subtype but also predict who can have better QOL with the disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Shobhna Bhatia, HOD, GI Department, Seth G. S. Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India for her collaboration to conduct the study at their gastroenterology OPD.

REFERENCES

- 1. [Last accessed on 2014 May 31]. Available from: http://www.romecriteria.org/assets/pdf/19_RomeIII_apA_885-898.pdf .

- 2.Upadhyay R, Singh A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Indian Scenario. [Last accessed on 2014 May 31]. Available from: http://www.apiindia.org/medicine_update_2013/chap56.pdf .

- 3.Tripathi B. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2001. Charak Chandrika Hindi Commentary, Charak Samhita; p. 758. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shastri A. 11th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1997. Sushruta Samhita – Āyurveda-tatva-sandipika Hindi Commentary; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey S, Pahwa P. Prakriti and its associations with metabolism, chronic diseases, and genotypes: Possibilities of new born screening and a lifetime of personalized prevention. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2014;5:15–24. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.128848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manyam BV, Kumar A. Ayurvedic constitution (prakruti) identifies risk factor of developing Parkinson's disease. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:644–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raut AA, Rege NN, Tadvi FM, Solanki PV, Kene KR, Shirolkar SG, et al. Exploratory study to evaluate tolerability, safety, and activity of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) in healthy volunteers. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012;3:111–4. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.100168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raut A, Bichile L, Chopra A, Patwardhan B, Vaidya A. Comparative study of amrutbhallataka and glucosamine sulphate in osteoarthritis: Six months open label randomized controlled clinical trial. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2013;4:229–36. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.123708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, DiCesare J, Puder KL. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: Development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1018831127942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoshkrood-Mansoori B, Pourhoseingholi MA, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Sedigh-Tonekaboni B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: A population based study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhalerao S, Deshpande T, Thatte U. Prakriti (Ayurvedic concept of constitution) and variations in platelet aggregation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:248. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shilpa S, Venkatesha Murthy CG. Understanding personality from Ayurvedic perspective for psychological assessment: A case. Ayu. 2011;32:12–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.85716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahalle NP, Kulkarni MV, Pendse NM, Naik SS. Association of constitutional type of Ayurveda with cardiovascular risk factors, inflammatory markers and insulin resistance. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012;3:150–7. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.100186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkataraghavan S, Sunderesan TP, Rajagopalan V, Srinivasn K. Constitutional study of cancer patients – Its prognostic and therapeutic scope. Anc Sci Life. 1987;7:110–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juyal RC, Negi S, Wakhode P, Bhat S, Bhat B, Thelma BK. Potential of ayurgenomics approach in complex trait research: Leads from a pilot study on rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 01]. Available from: http://www.pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid = 43008 .

- 17.Ghodke Y, Joshi K, Patwardhan B. Traditional medicine to modern pharmacogenomics: Ayurveda Prakriti type and CYP2C19 gene polymorphism associated with the metabolic variability. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:249528. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aggarwal S, Negi S, Jha P, Singh PK, Stobdan T, Qadar P, et al. EGLN1 involvement in high-altitude adaptation revealed through genetic analysis of extreme constitution types defined in Ayurveda. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18961–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006108107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]