Abstract

Background:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also called as hepatic steatosis is a manifestation of excessive triglyceride accumulation in the liver. NAFLD has been described by histological features ranging from simple fatty liver, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, progressive fibrosis, and liver failure.

Objective:

The objective was to evaluate the effect of herbomineral drugs and pathya (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise) in the management of NAFLD.

Materials and Methods:

It is a randomized, retrospective, open-ended study. A total of 32 patients presenting with raised alanine transaminase (>1.5 times normal levels) combined with sonological evidence of fatty liver in the absence of any other detectable cause of liver disease were included in the study. The recruited patients were randomly divided into two groups - The patients in Group-A (n = 21) were given a combination of herbomineral drugs Ārogyavardhinī vaṭi and Triphalā Guggulu along with prescription of pathya (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise); the patients in Group-B (n = 11) were advised only pathya.

Results:

Group-A (combined therapy group) showed statistically significant improvement in clinical symptoms, biochemical parameters-liver function test, lipid profile, fasting blood sugar, and body mass index (P < 0.001) in comparison to Group-B (pathya group).

Conclusion:

Combination of herbomineral drugs along with pathya has shown promising results toward the effective management of this metabolic disorder.

KEYWORDS: Cryptogenic cirrhosis, Medoroga, metabolic disorder, obesity, Yakṛt Roga

INTRODUCTION

Over the past couple of decades, it has become increasingly clear that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are the significant causes of liver disease. The prevalence of fatty liver disease in India is found to be as high as 24%,[1] which is similar to that reported in some of the Western countries, where it correlates with the prevalence of obesity.

Metabolic syndrome includes NAFLD as a risk factor in addition to other causes such as visceral obesity, hypertension, dysglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Starting from a simple steatosis, NAFLD can proceed to steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Cirrhosis and/or hepatic carcinoma can be its terminal complications.[2,3,4]

In Ayurveda, NAFLD may be understood as Yakṛt Roga (liver disease) and Medoroga (obesity).

A vast spectrum of diseases comes under Yakṛt Roga (liver disease) ranging from simple hepatic steatosis to hepatomegaly to liver cirrhosis. According to the Yogratnākara, vidāhī (spicy food) and abhiṣyandī āhāra (food which blocks the channels) leads to Rakta-kapha duṣṭi which may lead to Yakṛtodara.[5]

Obesity is a common metabolic disorder, and possibly is one among the oldest documented diseases. In Ayurveda as early as 1500 BC Caraka Samhitā described this condition as Sthaulya (obesity) and Medoroga (diseased state of fat metabolism).[6]

NAFLD is a metabolic disorder of hepatic origin. Thus, the treatment of NAFLD should be directed toward normalization of liver functions as well as to the reduction of insulin resistance.

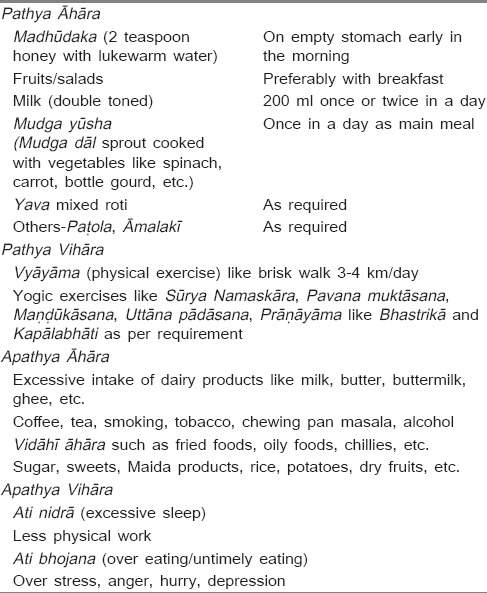

In this study two herbomineral drugs Ārogyavardhinī vaṭi (AV) and Triphalā Guggulu (TG) along with pathya (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise) [Table 1] were given to the patients.

Table 1.

Pathya-Apathya chart

Several clinical trials have proven the efficacy of AV in liver disorders.[7,8]

Ingredients of the other trial drug (TG) are Triphalā, Pippalī, and Guggulu, which are widely indicated in Medoroga and were presumed to be helpful reducing in insulin resistance.

Pathya āhāra includes diets such as yava, mudga, madhūdaka, etc., and vihāra includes vyāyāma as described in Caraka Samhitā in the context of Sthaulya cikitsā were also advised along with herbomineral drugs.[6]

The objective of the study was to examine the combined effect of two herbomineral drugs AV and TG along with pathya (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise) in the treatment of Yakṛt Roga vis-à-vis NAFLD.

This study revealed the effect of herbomineral drugs AV and TG along with pathya (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise) in the management of NAFLD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This retrospective, controlled, open labelled, series clinical study was conducted between 2011 and 2013 on 32 patients.

Selection of cases

Inclusion criteria

Clinical signs and symptoms suggesting of NAFLD/Yakṛt Roga, that is, pain in right upper quadrant/epigastric region of the abdomen, feeling of nausea, and vomiting, loss of appetite, burning sensation in the abdomen

Ultrasonography (USG) abdomen/or other scanning modalities such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen showing fatty infiltration of the liver

Biochemical: Liver function tests showing raised alanine transaminases (ALT) levels approximately more than 1.5 times the normal limits with/without raised lipid profile and fasting blood glucose levels within normal limits.

Exclusion criteria

Patients in whom alcohol intake exceeded 20 g/day (history of alcohol intake was taken separately from the patients and close relatives)

Patients with positive markers of other liver diseases such as viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's disease, alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency, hemochromatosis.

Trial drugs

Two classical herbomineral drugs were selected for the present study:

AV: As per Rasaratna sammuccaya[9] (parts of ingredients taken by weight)

Śuddha Pārada 1 part, Śuddha Gandhaka 1 part, Loha Bhasma 1 part, Abhraka Bhasma 1 part, Tāmra Bhasma 1 part, Harītakī 2 part, Vibhītakī 2 part, Āmalakī 2 part, Śhilajatu 3 part, Guggulu 4 part, Eraṇḍa 4 part, Kaṭukī 22 part. Bhāvanā with Juice extract of Nimba patra.

Dose: Two tablets of 125 mg twice daily after meals for 3 months.

TG: As per Śārṅgadhara Saṃhitā[10] (parts of ingredients taken by weight) Triphalā (Harītakī 1 part, Vibhītakī 1 part, Āmalakī 1 part), Pippalī 1 part, Guggulu 1 part.

Dose: Two tablets of 125 mg twice daily after meals for 3 months.

Grouping of patients

The selected patients were randomly divided into two groups namely Group A and Group B.

Group-A (combined therapy group)

A total of 21 patients were included in this group and were administered to herbomineral drugs (AV and TG) along with Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise, that is, pathya āhāra/vihāra which includes yava, madhūdaka, vyāyāma, etc.

Group-B (pathya Group)

Totally, 11 patients of NAFLD were included in this group and were subjected to only Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise, that is, pathya.

Criteria of assessment

Clinical signs and symptoms: Udaraśūla (pain in abdomen), utkleśa (feeling of nausea and vomiting), aruci (loss of appetite), hṛtkaṇṭhadāha (heartburn), etc., were assessed before and after the treatment. Clinical assessment was made by grading as 0, 1, 2, and 3 on the basis of severity.

Anthropometric measurement: Weight, height ratio (body mass index [BMI]).

Biochemical: Serum AST, serum ALT levels, serum triglycerides, fasting blood sugar levels

Radiological: USG abdomen/CECT abdomen.

Follow-ups

Total duration of the study was 3 months in which regular follow-ups of the enrolled patients were being done every 15 days. All biochemical investigations were done before starting and after every 1 month of treatment and scanning was done at the beginning and at the end of treatment. USG was done before and after 3 months of the treatment.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained in the clinical study before and after treatment was expressed in terms of mean, standard deviation with “n” as the number of observations. As the sample size is small (n ~ 30) paired t-test was applied to compare basal and final values. Level of significance was taken as P < 0.05. (Abbreviations: SD = Standard deviation, SE = Standard error, P = Actual probability value, n = number of observations).

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

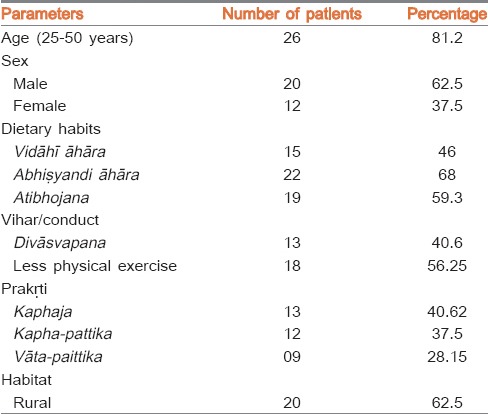

Out of 32 patients in the study, 12 patients were female and 20 patients were male which showed male predominance in the study. 81% of the patients were in between the age group of 25 and 55 years [Table 2]. Average BMI of the patients was 27.08 ± 2.20 kg/m2 ranging from 23.82 to 32.06 kg/m2.

Table 2.

Demographic profile

In our study, approximately 62% patients belong to the rural area and most of them were vegetarian with significant history of intake of plenty of milk and milk products (68%) and also with a history of excessive intake of spicy foods such as chillies (46%). 56.25% of patients didn’t do much of physical exercise and 40% had the habit of divāsvapana (day/afternoon sleeping). 40% of patient were having kapha predominant prakṛti and 62.5% were having kapha-paittika prakṛti [Table 2].

About 76% of enrolled patients presented with udaraśūla, that is, vague abdominal pain in right upper quadrant or in the epigastric region which was not affected by meals.

About 55% of the total patients had gastrointestinal complaints like utkleśa (feeling of nausea) and chardi (vomiting) and heaviness in the abdomens which are kapha predominant symptoms.

About 25% of patients presented with hṛtkaṇṭhadāha (burning in the epigastric region) which showed the paittika nature of the disease.

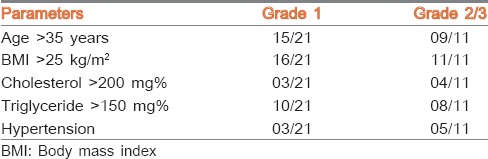

In the present study, 21 patients presented with Grade-1 fatty changes, nine patients showed Grade-2 fatty changes, and two patients presented with Grade-3 fatty changes through imaging studies.

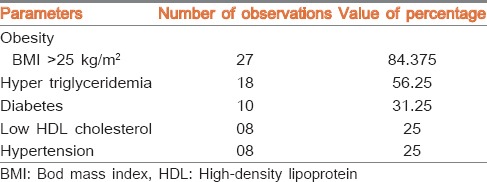

Eighteen patients showed raised triglyceride levels above the normal limits, and 10 patients had shown raised blood sugar levels [Table 3].

Table 3.

Prevalence of individual components of metabolic syndrome

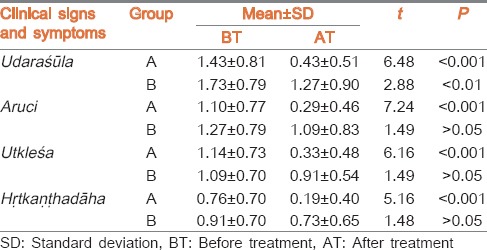

Combined therapy group (Group-A) showed significant improvement in their clinical symptoms such as udaraśūla, Aruci, utkleśa, and hṛtkaṇṭhadāha (P < 0.001) after treatment, whereas the pathya group (Group-B) did not show significant improvement in clinical symptoms, that is, aruci, utkleśa, and hṛtkaṇṭhadāha (P > 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effect of treatment on clinical symptoms

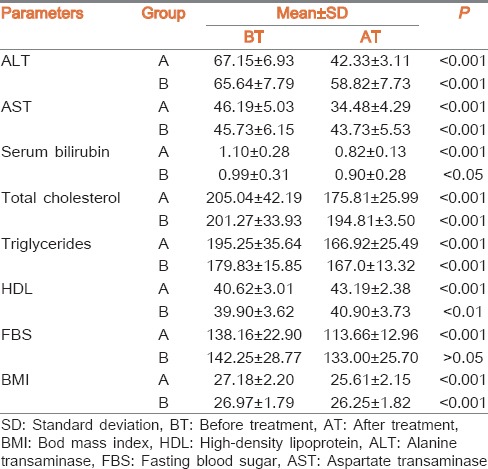

In the combined therapy group (Group-A) after 3 months of treatment, the mean BMI was reduced from 27.18 ± 2.20 to 25.61 ± 2.15. The mean ALT levels of the patients before treatment were 67.15 ± 0.93 which was reduced to 42.33 ± 3.11 after the treatment, which was statistically highly significant. Triglyceride levels reduced from initial value of 195 ± 35.64 to 166.92 ± 25.49 [Table 5].

Table 5.

Effect of treatment on biochemical parameters and BMI

In pathya group (Group-B) after 3 months of following pathya, the mean BMI was reduced from 26.97 ± 1.79 to 26.25 ± 1.82. The mean ALT levels of the patients before treatment were 65.69 ± 0.79 which was reduced to 58.82 ± 7.73 after the 3 months. Initial triglycerides levels before treatment were 179.83 ± 15.85 which was reduced to 167.0 ± 13.32 [Table 5]. The above results were statistically significant.

USG findings of Group-A showed normal scan in 12 patients of Grade-1 fatty changes and three patients had shown persisting mild fatty changes in comparison to their previous scans. One out of five patients with Grade-2 fatty liver showed normal sonography, three patients improved to Grade-1 fatty liver, and one patient had mild fatty infiltration. USG finding of patient with Grade-3 fatty infiltration had shown decreased echogenicity in comparison to her previous scan with Grade-2 changes.

In Group-B, six patients presented with Grade-1 fatty changes, four patients showed Grade-2 fatty changes and one patient presented with Grade-3 fatty changes. After 3 months of strict dietary restriction in Group-B patients four patients showed Grade-1 fatty changes, two patient with Grade-2 fatty changes and two patients showed mild fatty infiltration whereas no changes were found in the patient with Grade-3 fatty changes.

Group-A (combined therapy Group) had shown significant improvement in clinical signs and symptoms and biomedical parameters in comparison to Group-B (pathya Group).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates NAFLD to be a disease of middle age group with a mean age at a presentation being 37 years. Out of 32 patients, 20 patients were males. The reason for this male predominance has been described as a higher waist to hip ratio in men as compared to women, an indicator of central obesity and insulin resistance. This predilection of males to this disease has been seen not only in other studies from India,[1] but also in the United States.[11]

Available data show that majority of Indian patients with NAFLD had overweight or obesity as per Asia-Pacific criteria[1,12] (Patients with BMI of more than 23 were seen to be overweight and those with a BMI > 25 were labelled as obese by Asian standards, even though they do not have the kind of morbid obesity as seen in patients from the West). The mean BMI of the patients in our study was 27.08 ± 2.20 kg/m2 which was similar to data available in other studies from India,[1] but significantly lower than what has been described in the Western populations, where the mean BMI has always been reported to be above 30.[13] Indian patients despite having a lower BMI have similar fat percentage as the Western population.

About 68% of the total patients were having a history of intake of abhiṣyandī bhojana (food which blocks the channels such as milk products) and 46% of patients had the history of intake of spicy food. These type of food habit lead to kapha–pitta duṣṭi and rakta duṣṭi which may lead to Yakṛt Roga.[5]

Majority of patients of NAFLD had nausea/vomiting and burning in the epigastric region along with pain in the abdomen, which showed kapha-pitta predominance of the disease.[5]

In our study, 21 patients had minimal or mild inflammation (Grade-1). Moderate (Grade-2) inflammation was present in nine patients and severe (Grade-3) inflammation was present in only two patients. None of our patients had advanced liver disorder like liver cirrhosis.

This is in contrast to the reported series from the West where advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis has been demonstrated to be present in up to 50% of NAFLD data.[2] Recently, there have been reports linking the development of hepatocellular carcinoma to NASH.[2,3]

Out of 32 patients, 18 patients showed raised triglycerides levels and 10 patients showed raised blood sugar levels, which was indicative of metabolic association of the disease [Table 3].

Our study shows that factors associated with severity of disease, that is, age >35 years, BMI >25 kg/m2, cholesterol levels >200 mg%, triglyceride levels >150 mg% were associated in patients with advanced grade of inflammation (Grade-2 fatty liver Grade-3 fatty liver) [Table 6].

Table 6.

Factors associated with advanced grade of inflammation

Effect of the treatment

Patients in the combined therapy Group (Group-A) showed significant improvement in their clinical symptoms, biochemical parameters (ALT, triglycerides, fasting blood sugar levels), as well as in BMI after the completion of therapy in comparison to pathya group (Group-B). This proves the superiority of combined therapy over pathya therapy (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise) in treating this metabolic disorder [Tables 4 and 5].

Group-A showed significant improvement in clinical symptoms viz., pain in abdomen, nausea-vomiting, loss of appetite, and burning sensation in the epigastric region.

The effect of the treatment in biochemical parameters of combined therapy group (Group-A) was encouraging. Patients of Group-A had their ALT levels move toward normalization and there was also a significant mean decrease in their triglyceride levels after the treatment.

Mean BMI of the patients of Group-A decreased from 27.18 ± 2.20 to 25.61 ± 2.15 kg/m2, which was highly significant (P < 0.001).

The overall result of the treatment of Group-A implied that combination of herbomineral drugs along with pathya/apathya were not only helpful in improving liver functions, but were also supportive in reducing the BMI and triglyceride levels and hence reduced the insulin resistance.

Patients in Group-B showed improvement in their ALT levels and mean BMI, but did not show marked improvement as compared to Group-A [Table 5]. This suggests the significance of dietary restrictions and physical exercises in the management of NAFLD, but not to the extent of treatment with Ayurvedic drugs.

Probable mode of action of Trial drugs: (Ārogyavardhinī vaṭi and Triphalā Guggulu)

Ārogyavardhinī vaṭi contains Kaṭukā (Picrorhiza kurroa) as the major ingredient (50%). Kaṭukā is titka rasa pradhāna, thus helpful in āma-pachana. Other ingredients of AV are Loha Bhasma, Tāmra, Śilajatu (Asphaltum), Guggulu (Commiphora mukul) which are having lekhanīya karma (action)[9] Triphalā (Harītakī – Terminalia chebula; Vibhītakī – Terminalia bellerica; Āmalakī – Emblica officinalis) is dīpanīya, śleṣma-pittaghnī, meha-śothaghnī.[14]

Kaṭukā is a proven hepatoprotective drug by action as is confirmed by several studies. A study of standardized extracts of P. kurroa (Kaṭukā), in experimental fatty liver disease in rats showed that P. kurroa regressed several features of NAFLD such as lipid content of the liver tissue, morphological regression of fatty infiltration, hypolipidemic activity.[7,8] Pattanaik et al.[15] reports lipid peroxidation and free radical scavenging properties of Tāmra Bhasma. Buwa et al.[16] has confirmed the hepatoprotective action of Abhraka Bhasma.

Thus, Ārogyavardhinī vaṭi acts as primarily a hepatoprotective and thereby was helpful in improving liver functions in patients of NAFLD.

Triphalā Guggulu is a mixture of (i) Triphalā (Harītakī – Terminalia chebula; Vibhītakī – Terminalia bellerica; Āmalakī – Emblica officinalis), (ii) Pippalī (Piper longum), and (iii) Guggulu (Commiphora mukul) combined using bhāvanā of Triphalā decoction. Triphalā has dīpanīya action of improving metabolic fire, śleṣma-pittaghnī, meha-śothaghnī (improving urinary disorders and swelling), rasāyanī (improving rejuvenating power).[10] Pippalī is medah–kaphanāśaka (reducing body fat) and Guggulu is ati-lekhana, srotaśśodhaka (Purifier of the channels).[14]

Thus, TG is lekhanīya by action and thereby useful in reducing the triglyceride levels along with body fat in patients of NAFLD.

Role of pathya/Apathya in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Pathya āhāra such as madhu, yava, etc., are rūkṣa in guṇa (property), śleṣma-medohara, and lekhanīya in karma (action).[17,18] Mudga is kapha-pitta nāśaka. Pathya vihāra such as vyāyāma (Physical exercise), which was advised to the patients of NAFLD, has been counted as a type of langhana and was, therefore, helpful in reducing body fat.[19]

Thus, the recommended Ayurvedic diet as per the constitution of patient (pathya āhāra) and exercises (pathya vihāra) were helpful in reducing BMI. Pathya supported not only in reducing insulin resistance but was also useful in reducing the fat accumulated in the liver thus improving the liver functions. We can thus infer that pathya āhāra/vihāra proved useful as an adjunct therapy for management of NAFLD.

CONCLUSION

NAFLD is a metabolic syndrome of hepatic origin mostly occurring in middle-aged males and commonly associated with obesity.

Substances which possess lekhanīya and medohara karma (fat reducing action) would be beneficial in NAFLD patients because they decrease the body fat and thus not only improve lipid profile and BMI but also may be helpful in improving the liver function.

Pathya (Ayurvedic dietary regime and physical exercise) alone has not been found sufficient to treat this syndrome. Instead, a combination of herbomineral drugs (AV and TG) and pathya/apathya have resulted in significant improvement in liver functions and BMI of NAFLD patients.

To get more significant results, this study needs to be conducted on larger sample size.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh SP, Nayak S, Swain M, Rout N, Mallik RN, Agrawal O, et0 al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in coastal Eastern India: A preliminary ultrasonographic survey. Trop Gastroenterol. 2004;25:76–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bugianesi E, Leone N, Vanni E, Marchesini G, Brunello F, Carucci P, et al. Expanding the natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: From cryptogenic cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:134–40. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshioka Y, Hashimoto E, Yatsuji S, Kaneda H, Taniai M, Tokushige K, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and burnt-out NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1215–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shastri SB, editor. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Prakashan; 2009. Yoga Ratnakar, Commentary by Vaidya Sri Laxmipati Shastri. Udara Rogachikitsa: Ver. 17; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varanasi: Chaukhamba Bharti Academy; 1998. Agnivesh, Charak Samhita, Hindi commentary by Kashinath Pandey and Gorakh Nath Chaturvedi, Sutra Sthana 21: Ver. 25-28; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antarkar DS, Tathed PS, Vaidya AB. A pilot phase II trial with arogya-wardhani and Punarnavadi-Kwath in viral hepatitis. Panminerva Med. 1978;20:157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shetty SN, Mengi S, Vaidya R, Vaidya AD. A study of standardized extracts of Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth in experimental nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2010;1:203–10. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.72622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giri K, editor. Varanasi: Published by Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 2009. Vagabhatta, Rasratnnasammuchaya, Hindi commentary Rasaprabha by Indradev Tripathi. Kustha Rogadhikar. Ver. 87-93; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varanasi: Published by Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2009. Sharangdhara's Sharangdhara Samhita with Commentary by Shailza Srivastava. Madhyamakhanda 7. Ver. 82-83; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Determinants of the association of overweight with elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:71–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Sydney, Melbourne, Australia: WHO/IASO/IOTF: Published by Health Communications Australia Pty Limited; 2000. Western Pacific Region. Asia-Pacific perspective. Redefining Obesity and its treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teli MR, James OF, Burt AD, Bennett MK, Day CP. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: A follow-up study. Hepatology. 1995;22:1714–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chunekar KC, Pandey GS, editors. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharti Academy; 2006. Bhavamishra, Bhavaprakasha Nighantu. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pattanaik N, Singh AV, Pandey RS, Singh BS, Kumar M, Dixit SK, et al. Toxicology and free radicals scavenging property of Tamra bhasma. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2003;18:181–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02867385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buwa S, Patil S, Kulkarni PH, Kanase A. Hepatoprotective action of abhrak bhasma, an ayurvedic drug in albino rats against hepatitis induced by CCl4. Indian J Exp Biol. 2001;39:1022–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.11th ed. Varanasi: Published by Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1997. Sushruta, Sutra Sthana 45:132, Hindi commentary by Dr Ambika Datt Shastri: Sushruta Samhita, Ayurved Tatva Sandipika; p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.11th ed. Varanasi: Published by Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1997. Sushruta, Sutra Sthana 46:42, Hindi commentary by Shastri AM. Sushruta Samhita, Ayurved Tatva Sandipika; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varanasi: Chaukhamba Bharti Academy; 1998. Agnivesha, Charaka Samhita, Hindi commentary by Pandey K, Chaturvedi GN. Sutra Sthana 22: Ver. 18; p. 427. [Google Scholar]