Abstract

Background:

Tobacco smoke has adverse health effects on women of the reproductive age group with serious health implications for the next generation.

Objectives:

This study assessed the prevalence of current active smoking, second-hand smoke (SHS) exposure and the factors influencing smoke exposure in females of the reproductive age group.

Materials and Methods:

Data from the nationally representative Global Adult Tobacco Survey-India (GATS 2009) was analyzed for socio demographic variables, tobacco-related variables and knowledge variables.

Results:

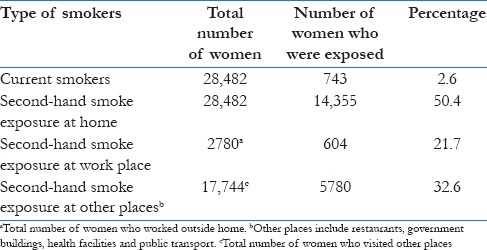

50.4% of the women in the reproductive age group had been exposed to SHS at home, though only 2.6% of the women were current active smokers. This was more than the SHS exposure at work (21.7%) and elsewhere (32.6%). SHS exposure of the women at home did not vary significantly with knowledge of adverse effects of smoking but was affected by the place of dwelling as the smoke exposure was found to be more among rural women.

Conclusion:

SHS exposure is more prevalent than current active smoking in women of the reproductive age group and that too at home. Thus, policies need to be framed in order to curb this menace which is a vicious one as women don’t really have an alternative as far as this exposure is concerned.

Keywords: Knowledge, reproductive age, second-hand smoke, smoking, tobacco

Introduction

Global evidence suggests that tobacco, in the form of smoking as well as second-hand smoke (SHS), has significant health implications in women of the reproductive age group.[1,2] Tobacco kills approximately 6 million people all over the world.[3] Inhalation of SHS by non-smokers accounts for another 600,000 of premature deaths.[4] SHS is a mixture of the smoke given off by the burning end of tobacco products (side-stream smoke) and the mainstream smoke exhaled by smokers. It is well documented that long-term exposure to SHS leads to lung cancer and coronary heart disease in non-smoking adults.[3] Thus, the fatal effects of SHS are comparable with the adverse effects of active smoking.

Many studies have ventured to find out the effect of smoking on the pregnancy outcomes.[1,3,5]

Evidence also suggests that SHS exposure in women of a reproductive age can cause adverse reproductive health outcomes similar to active tobacco smoking such as pregnancy complications, fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, stillbirths, and infant death.[5] However, there are dearth of studies which have explored the factors influencing the exposure of women in the reproductive age group to the tobacco smoke inhalation. Few studies have shown that smoking in women has association with lower education, lower socio-economic status as well as the ethnicity.[6,7] But no studies in India have been done to assess the factors associated with SHS exposure in the women.

The present study was planned with the objectives to find out the prevalence of current active smoking and SHS exposure in females of the reproductive age group, to find out the factors influencing the habit of current active smoking, and the SHS exposure among women of the reproductive age group.

These factors have revealed newer facets of tobacco exposure. This could help in formulation of behavioral change strategies as well as improvements needed in the current legislations in order to reverse the tobacco epidemic among the women.

Material and Methods

For the purpose of the study, we analyzed data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey-India (GATS 2009) which is available on the internet as GATS India Report 2009–10. This was a cross-sectional survey covering the whole country that was conducted using a nationally representative probability sample to provide estimates of tobacco use and its various dimensions. The survey involved multistage cluster sampling method and covered all non-institutionalized people above 15 years of age.

For this study, the study population was women in the reproductive age group, i.e. from 15 to 49 years. From the GATS India data, we analyzed the various socio-demographic parameters like age, residence (type of residence-rural/urban), education and occupation. Responses of current smoking for these variables were analyzed. For the analysis, ages were classified into three groups: 15–26 years, 27–38 years and 39–49 years. Education was regrouped into three groups: Less than primary, primary to senior secondary and graduate and above. Similarly, occupation was regrouped into: Employed, students and not employed.

Exposure to SHS was assessed separately on three places–home, workplace and elsewhere (restaurants, government building, public transport and health facility). Exposure at home was taken as positive if the respondent's answer for “how often does anyone smoke inside your home” was any of the responses viz. daily, weekly, monthly or less than monthly. This was done because even if the woman has been exposed to tobacco smoke even once in a few months, the health risks remain there. Risk of exposure to tobacco smoke at work place was calculated from among those women who were working outside their home including both indoors and outdoors. SHS exposure elsewhere was taken as positive if the woman had seen people smoking at any of these places to which she had gone in the last 30 days-restaurants, government offices or buildings, health facilities and/or public transport.

For those who were exposed to SHS, apart from socio-demographic factors, knowledge whether SHS inhalation caused health problems was also assessed. The dependent variables were current smokers and exposure to SHS in the last 30 days.

The study was exempted from ethics review by the Chairperson of the Ethics Advisory Group of International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France, as it was a secondary analysis of existing dataset and did not involve any direct interaction with human participants.

The data was then analyzed using SPSS 10 and chi-square test and odd's ratio were calculated to find out the association between the variables.

Results

More number of women in the reproductive age group belonged to the younger age group (15–38 years; 76.5%), most of them had education less than or up to senior secondary (90.0%) and majority of them were not employed (65.3%). Approximately, 61% of the women resided in rural areas.

The number of women in the reproductive age group who were current smokers was 2.6%. For those women who confirmed that smoking was allowed at their home, more than half (50.4%) had been exposed to SHS at home [Table 1].

Table 1.

Prevalence of exposure by active smoking and second-hand smoking, among women of the reproductive age group in India, GATS 2009-10

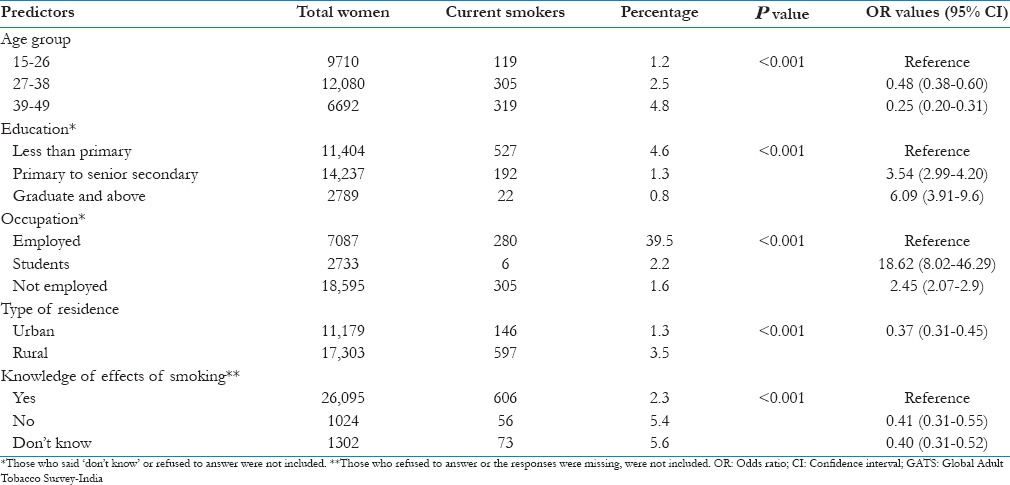

Socio-demographic factors like age, education, occupation and residence as well as knowledge regarding adverse effects of smoking on health significantly influenced the rate of current smokers among women of the reproductive age group (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Predictors of current active smokers among women of the reproductive age group in India, GATS 2009-10

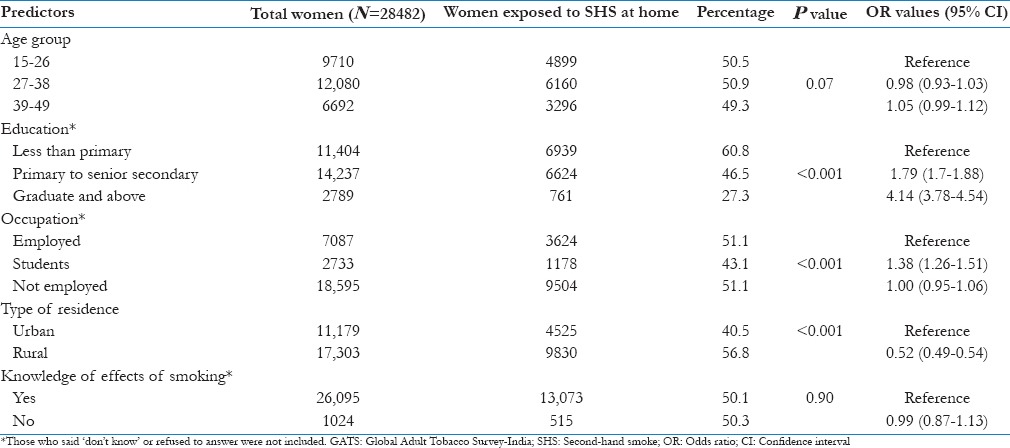

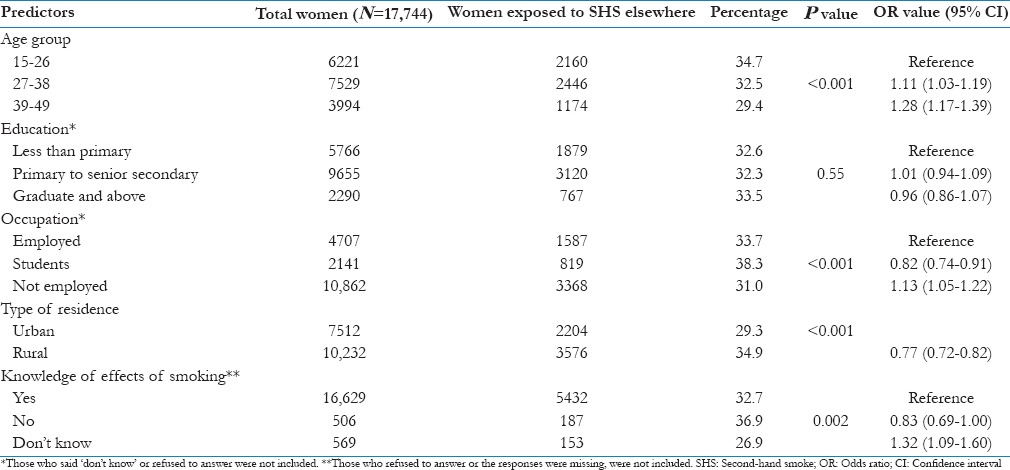

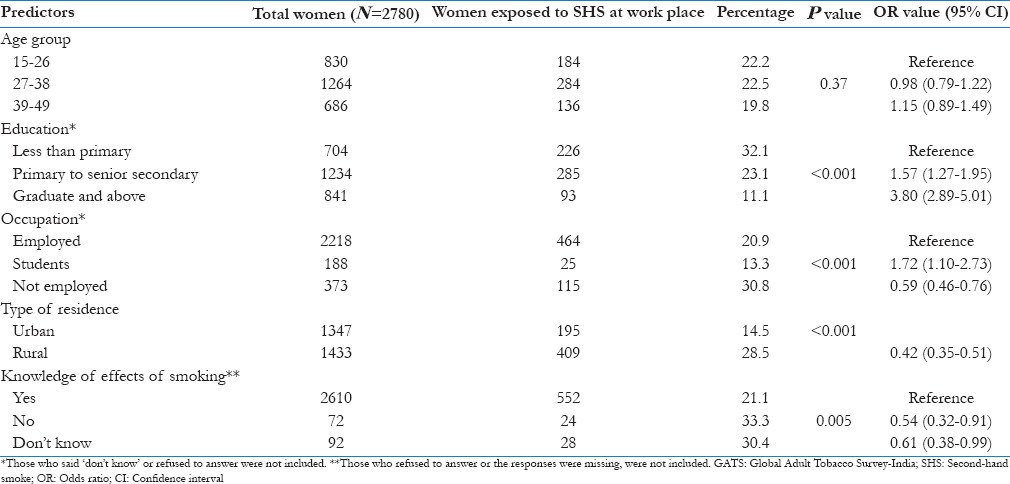

For SHS exposure, age was not found to have a significant association with exposure at home and at work place while it significantly influenced the exposure at other places (P < 0.001). Similarly, education of the woman was not found to be significantly related to the exposure to SHS elsewhere, but the relationship was statistically significant for exposure at home and at work place; exposure decreased with higher education (P < 0.001 in both). The other factors like occupation and place of residence were found to be significantly associated with the SHS exposure in women of reproductive age at all places. However, knowledge regarding adverse effects of smoking on health had no effect on the exposure to SHS at home (P = 0.90) but was significantly related to SHS exposure at work and elsewhere [Tables 3-5].

Table 3.

Predictors of second-hand smoke exposure at home, among women of the reproductive age group in India, GATS 2009-10

Table 5.

Predictors of second-hand smoke exposure elsewhere, among women of the reproductive age group in India, 2009-10

Table 4.

Predictors of second-hand smoke exposure at work place, among women of the reproductive age group in India, GATS 2009-10

Discussion

The analysis of GATS data for women of the reproductive age has thrown light on certain interesting facts. It reveals that practice of current smoking in the women is influenced by age, education, occupation, place of residence and knowledge of adverse effects of smoking on health. According to a study done by Fronczack et al., in Poland on adults, the number of current tobacco smokers was inversely proportional to the level of education, which is in line with our finding.[8]

The women were exposed to SHS at home more than anywhere else (50.4% at home as compared to 21.7% at workplace and 32.6% elsewhere). In another study using GATS data for Bangladesh, the extent of SHS in females at various places was found to be similar.[9] But in a study done on non-smoking adults in Canada in 2003, SHS exposure was found to be more in public places and in younger adults.[10] Similar study in Nigeria revealed that SHS exposure was more in public places and 19.5% of women had been exposed to SHS in the period of the study.[11] In a study done on non-smoking pregnant women in Spain by Aurrekoetxea et al., low educational level was associated with more SHS exposure and SHS exposure was found to be the most at home.[7] In a New York city study on non-smoking pregnant women, the authors found a similar relationship between educational level of the woman, her ethnicity and her SHS exposure.[12] Our study as well as the study in Spain[7] has found that the SHS exposure was maximum at home. This is alarming as we don’t have any policy for control of SHS home exposure as of now. Age of the woman, her knowledge about the health effects of smoking and status of employment hardly affected her SHS exposure at home. This is due to the fact that for females, there is no replacement for home.

At the work place, the SHS exposure was not found to have any relationship with age of the woman but her level of education affected the SHS exposure at work. The higher the educational qualifications, less was the exposure. Students had a lower risk of SHS exposure at work place, probably since they were not involved in outdoor work. This exposure was more in rural areas and among those who were not employed with any organization. It may be because in the rural areas, women were working outdoors in the fields with their husbands and thus being exposed to SHS. Significant association was observed between knowledge regarding adverse effects of smoking and the SHS exposure at work. Those who had knowledge about it were less exposed as compared to those who had no knowledge or did not give a definite answer. Moreover, bans on public smoking are more stringent in urban areas whereas the rural areas, especially the farms and fields don’t have a comprehensive monitoring system in this respect.

Exposure to SHS elsewhere was significantly related to all the factors except education. More SHS exposure elsewhere was observed in the younger age groups, students, in rural areas and those who did not have knowledge of adverse effects of smoking on health. Similar results were reflected in a study done in Nigeria where SHS exposure at public places was 19.5% in women.[11]

Limitations of Study: The study involves the analysis of GATS 2009–10 data for India. This data has no references to the socio-economic status of the respondents which is an important factor influencing exposure to tobacco smoke.

Conclusion and Recommendation

From the analysis of the GATS-India, 2009–10, it can be concluded that second-hand smoke exposure is more prevalent than current active smoking in women of the reproductive age group. The SHS exposure is highest at home, in rural areas, in women who have less than senior secondary level of education and in students who visit other places like public building, health facility and restaurants, and used public transport. Thus, policies need to be framed in order to curb this menace which is a vicious one as women don’t really have an alternative as far as this exposure is concerned.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mortality trends for selected smoking-related and breast cancer- United States, 1950-1990. MMWR. 1993;42:857,863–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society; 1996. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures-1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization; [Last accessed on 2014 May 26]. Tobacco Fact Sheet No. 339. Available from: http://www.who_tobacco.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Last accessed on 2014 May 29]. Available from: http://www.Tobacco Statistics and Facts-ASH) Action on Smc .

- 5.Khattar D, Awasthi S, Das V. Residential environmental tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy and low birth weight of neonates: Case control study in a public hospital in Lucknow, India. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:134–8. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0035-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults- United States, 1995. MMWR. 1997;46:1217–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aurrekoetxea JJ, Murcia M, Rebaqliato M, Fernández-Somoanod A, Castillad AM, Guxens M, et al. Factors associated with second hand smoke exposure in non-smoking pregnant women in Spain: Self-reported exposure and urinary cotinine levels. Sci Total Environ. 2014;470:1189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fronczak A, Polariska K, Dziankowska-Zaborszczyk E, Bak-Romaniszyn L, Korytkowski P, Wojtyła A, et al. Changes in smoking prevalence and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke among adults in Lodz, Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:754–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palipudi KM, Sinha DN, Choudhury S, Mustafa Z, Andes L, Asma S. Exposure to tobacco smoke among adults in Bangladesh. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:210–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez CE. Second-hand smoke exposure- who's at risk? Health Rep. 2004;16:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desalu OO, Onyedum CC, Adewole OO, Fawibe AE, Salami AK. Second hand smoke exposure among non smoking adults in two Nigerian cities. Ann Afr Med. 2011;10:103–11. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.82069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins SS, Dacey C, Gennaro S, Keshinover T, Gross S, Gibeau A, et al. Second hand smoke exposure among non-smoking pregnant women in New York City. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu034. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]