Abstract

As of 2013, the latest statistics available, more than 400,000 individuals are lodged in Indian prisons. Prisoners represent a heterogeneous population, belonging to socially diverse and economically disadvantaged sections of society with limited knowledge about health and healthy lifestyles. There is considerable evidence to show that prisoners in India have an increased risk of mental disorders including self-harm and are highly susceptible to various communicable diseases. Coupled together with abysmal living conditions and poor quality of medical services, health in prisons is a matter of immense human rights concern. However, the concept and the subsequent need to view prison health as an essential part of public health and as a strategic investment to reach persons and communities out of the primary health system ambit is poorly recognized in India. This article discusses the current status of prison healthcare in India and explores various potential opportunities the “prison window” provides. It also briefly deliberates on the various systematic barriers in the Indian prison health system and how these might be overcome to make primary healthcare truly available for all.

Keywords: Health policy, human rights, infectious disease, mental health, primary health, primary healthcare, prison, public health, self-harm

“It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.”

--Nelson Mandela[1]

Introduction

More than 10.2 million people worldwide are held in prisons.[2] As per the World Prison Population List-2013,[3] there is a general trend of growth in prison population in majority of nations, including in India. As of 2013, the latest figures available for India, there are 4,11,992 prisoners (including pre-trial detainees).[4] More importantly, prisoners do not represent a homogenous cross section of the society.[5] Majority of prisoners in India are uneducated, poor,[4] and belong to marginalized or socially disadvantaged groups and have limited knowledge about health and practice unhealthy lifestyles. Thus, they represent a distinct and vulnerable health group needing priority attention.

While putting aside the fact that the ignorance of the health of prisoners is an issue of immense human rights concern – the need to control disease in prisons as a part of the larger agenda of public health and a part of primary healthcare is a concept yet to catch up in India. This article discusses the current status of prison healthcare in India and explores various potential opportunities which the “prison window” provides to reach those sections of the society who do not or are incapable of accessing primary healthcare facilities.

Prisons and Communicable Diseases In India

Owing to increasing crime rates, rise in population, and a more authoritative judicial system (leading to higher conviction rates), there is severe overcrowding and exhaustion of prison facilities in India. This makes the prison environment rather unhealthy and it serves as “hot-spots” for infectious disease transmission. The walls of the prison however cannot prevent disease transmission – thereby making prison health a very significant part of public health.[6,7,8] Most prisoners are imprisoned for only very short periods of time. More than one third of prisoners are imprisoned for less than 3 months in India.[4,9] Thus, there is a great deal of interaction between the two communities on either side of prison walls. The continuum with society is also ensured via the prison staff. Even if prisoners are not released there is significant interaction within the prison-system itself – prisoners being circulated in different cells, different prisons, between judiciary systems and jails and even between prisons and health centers.

Prisoners are known to be at a high risk for diseases like sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV-AIDS, hepatitis B and hepatitis C. A study published in 2007[10] reported that in 20 countries, HIV prevalence was more than 10% within prison populations. Evidence regarding the high burden of HIV/STIs in Indian prisoners is available[11,12] but scarce. A study[13] on the prevalence of HIV in Indian prisons revealed that 1.7% of male and 9.5% of female inmates were HIV positive. This is significantly higher than the national HIV prevalence of 0.32% in males and 0.22% in females.[14]

Various factors have been implicated for this including intravenous drug abuse and frequent visitations to sex workers. The report on “Prevention of spread of HIV amongst vulnerable groups in South Asia”[15] from United Nations office on drug and crimes revealed that 63% of prisoners in India had a history of drug abuse. The prevalence of drug abuse varies between 8% to 63% among Indian prisoners.[13] Continuance of high risk behaviors such as unprotected sex[13] and substance abuse[16,17] after release from prison is also very common. Lack of conjugal life in prisons has also led to prisoners engaging in male-to-male sexual acts.[12,13] A study conducted in a North Indian jail revealed that 28.8% were homosexual or bi-sexual, 68% had multiple partners and 80.6% engaged in unprotected sex.[12] Intravenous drug abusers generally have criminal history (mostly for minor crimes), and they too avoid utilizing health services for fear of persecution, ostracism and discrimination.

Consensual homosexual encounters are considered a criminal offence in India which entails a maximum punishment of life imprisonment.[18] The LGBT (lesbian-gay-bisexual-transsexual) community has also faced tremendous stigma and is by and large outside the radars of primary health care systems. As such prisons might be the only opportunity for the health system to appropriately intervene with these individuals and their communities to evaluate their health needs and problems. If appropriately utilized primary healthcare professionals might use the “prison window” to impart knowledge of healthy lifestyles and habits including safe sex practices and drug de-addiction services. An additional benefit of such health education campaigns might actually be that knowledge so acquired will be passed on to their own marginalized communities which are mostly out of reach of the government's primary healthcare system due to their closed nature owing to stigmatization in the larger society. In fact, these prisoners can be potentially rehabilitated as community primary healthcare workers. Over time they would become a team of dedicated community health workers who can easily help establish communication and expand networks into the hitherto unreachable sections of societies like the LGBT community.

Occupancy rates in prisons vary between states with the national average for 2013 being 118.4% up from previous years.[4] This apart from a combination of other factors like inadequate ventilation, poor nutritional status of prisoners,[19] unsafe sex practices and needle-sharing habits all add up to why tuberculosis (TB) is very commonly seen in Indian prisons. High rates of TB have been reported by Human Rights Watch in India and a study in 2008 had found that 9% of prison deaths was attributed by TB.[20] In fact, a study from Brazil has empirically demonstrated transmission of TB from prison to community by showing that 54% of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in an urban population “were related to strains from persons in prisons.”[21] With HIV being another one of the major killers in prisons and the specter of MDR-TB looming large over the nation, urgent emphasis to TB control in prisons is crucial for control of TB in the community at large.

Mental Health, Drug Abuse and Suicide in Indian Prisons

Mental illness is yet another significant public health problem and its prevalence among prisoners is very high. Identification and treatment of people with mental health conditions is of utmost importance for the cause of justice as well as to ensure provision of basic human rights – an important ethos of the Indian constitution and culture. Studies done internationally have found the prevalence of mental illnesses to be three times higher in prisons when compared to the general population.[22] However, the official prison statistics of India – 2012 report that only, “1.9% of convicted, 0.8% of under-trial detainees and 0.4% of detained inmates” as mentally ill.[4] A comprehensive mental health program is needed to thus estimate the true prevalence in prisons.

Drug abuse is an identified problem among criminals and there is a need to provide detoxification facilities in the prison itself instead of the current practice of shifting to hospitals for treatment of withdrawal symptoms. It is also important to ensure that those on de-addiction treatments in prisons are followed up till completion of their treatment schedules in the community once released. Counseling for inmates, particularly women should form an integral part of health care provisions within prisons and continuity of these services even after they are released is essential to ensure successful rehabilitation. It is evident from these facts that involving primary healthcare professionals in prisons becomes essential.

The proportion of deaths due to suicide in Indian prisons has been reported to be as high as 5–8%.[23] A study in 2008 reported suicide as a cause for 11% of prison deaths.[20] Unnatural custodial deaths particularly suicides often leads to allegations of police brutality and torture. A robust prison health system capable of identifying prisoners at high risk of committing suicide and provision of timely interventions would be extremely beneficial and help avoid unnecessary controversies.

Gaps in Current Prison Health Policies and Their Implementation

The model prison manual for India[24] has iterated in details the constituents and requirements of medical care to prisoners. Unfortunately, the gap between stated policy and actual practice is far too wide. For example, the prison policy in India lays emphasis on ensuring proper standards for ventilation, sanitation and hygiene. Yet Indian prisons have consistently been rated poorly by human rights activists for not being able to provide these basic living standards.[25]

Prison inmates who are completely dependent on the state for provision of even basic medical care are often side-lined citing security and safety concerns. Basic healthcare provided in prisons is seen as cheap care and there is a need to provide primary healthcare services in standards no less that that provided to non-prison citizens of India. A previously published human rights report[25] suggests that even the primary health care services being provided in Indian jails is of poor quality. The report had noted that for most parts, it meant “dispensation of one drug, which was described to us as a pain killer that reduced fever – perhaps aspirin.”[25]

Prison policies in India prevent condom distribution policies,[13] despite strong evidence that prisoners engage in high-risk behaviors. There are neither any permanent HIV/STI education programs being run in most prisons nor any prison-based needle and syringe programs[13] Proper screening for infectious diseases like HIV, STIs and TB in addition to measures to prevent their transmission need to be implemented probably at standards higher than that provided by national health programs at the community level (since they represent a high-risk vulnerable population.).

Linking Prison Health With Primary Health: The Way Forward

Politicians, policy makers and the general public in India are prejudiced by the traditional notion that “sinners deserve neither mercy nor money.” Owing to this mind-set policy makers tend to allocate the resources “as per law” rather than “as per needs.” Even this is provided only after significant lobbying by pressure groups like human/prison rights activists. Sadly the media too presents prison health as a human rights issue and not an issue of public health concern. The very fact that almost all prisoners return back to the community makes it imperative to link prison health with the public health system and bring them under the coverage of primary health care. Policy makers as well as the general public need to understand that the prison and the community are at continuum. The much needed overhaul of the prison health system by linking it with public health cannot be achieved without a sustained campaign aimed at changing these dogmas. Historical data from nations which have separate health systems for prisons clearly indicate very poor quality of services.[19]

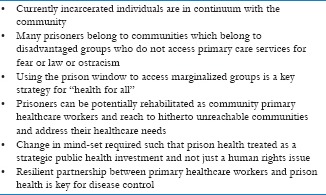

The need of the hour is a major renovation of prison health policies (Box 1). There is an urgent need for further research on various aspects of prison health and particularly its epidemiology. Factors which propagate the spread of disease from communities to prisons and vice versa need to be studied and interventions to control them must be implemented. A resilient partnership between primary healthcare professionals and prison authorities can pave the way for achieving the desired changes in the existing prison health care system, thereby increasing the overall well-being of those serving their sentences and the community as a whole.

Box 1:

Key Messages: Using prison window to reach disadvantaged groups in primary care

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in the article are personal opinion of the author and might not be subscribed by author's employers and/or funders.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wikipedia. [Last cited on 2014 Dec 18]. Available from: http://www.en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Nelson_Mandela .

- 2.Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377:956–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walmsley R. 10th edition. London: International Centre for Prison Studies; 2013. [Last cited on 2015 Feb 20]. World prison population list. Available from: http://www.images.derstandard.at/2013/11/21/prison-population.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Crime Records Bureau. Prison Statistics of India 2013. [Last cited on 2014 Dec 28]. Available from: http://www.ncrb.gov.in/PSI-2013/Full/PSI-2013.pdf .

- 5.Berkman A. Prison Health: The breaking point. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1616–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.12.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenda J, van den Bergh, Gatherer A, Fraserb A, Mollera L. Imprisonment and women's health: Concerns about gender sensitivity, human rights and public health. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:689–94. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.082842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 23]. Moscow declaration on prison health as part of public health. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/98971/E94242.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 23]. Health in prisons project. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/prisons . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy M. Prison health services. BMJ. 1997;315:1394–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolan K, Kite B, Black E, Aceijas C, Stimson GV. Reference Group on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care among Injecting Drug Users in Developing and Transitional Countries. HIV in prison in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:32–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundar M, Ravikumar KK, Sudarshan MK. A cross-sectional seroprevalence survey for HIV-1 and high risk sexual behaviour of seropositives in a prison in India. Indian J Public Health. 1995;39:116–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh S, Prasad R, Mohanty A. High prevalence of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections amongst the inmates of a district jail in Northern India. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10:475–8. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolan K, Larney S. HIV in Indian prisons: Risk behaviour, prevalence, prevention and treatment. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:696–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Press Information Bureau. HIV Estimations 2012 Report Released. [Last accesses on 2012 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.pib.nic.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=89785 .

- 15.New Delhi: UNODC; 2008. UNODC. Prevention of spread of HIV amongst vulnerable groups in South Asia: Our work in South Asian prisons. [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacGowan RJ, Margolis A, Gaiter J, Morrow K, Zack B, Askew J, et al. Project START Study Group. Predictors of risky sex of young men after release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:519–23. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolan K, Wodak A, Hall W, Gaughwin M, Rae F. HIV risk behaviour of IDUs before, during and after imprisonment in New South Wales. Addiction Res. 1996;4:151–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh A. Gay sex illegal, says Supreme Court. The Indian Express Dec 11. 2013. [Last cited on 2014 Apr 02]. Available from: http://www.indianexpress.com/news/gay-sex-illegal-says-supreme-court/1206233 .

- 19.Simooya OO. Infections in Prison in Low and Middle Income Countries: Prevalence and Prevention Strategies. Open Infect Dis J. 2010;4:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Math SB, Murthy P, Parthasarathy R, Kumar CN, Madhusudan S. Mental Healh and Substance Use problems in prisons. The Bangalore Prison Mental Health Study: Local lessons from National Action National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/prison/pg010.html .

- 21.Sacchi FPC, Praça RM, Tatara MB, Simonsen V, Ferrazoli L, Croda MG, et al. Prisons as reservoir for community transmission of tuberculosis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 19]. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2103.140896 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.HM Inspectorate of Prisons. The mental health of prisoners. A thematic review of the care and support of prisoners with mental health needs. HM Inspectorate of Prisons October. 2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/publications/inspectorate-reports/hmipris/thematic-reports-and-research-publications/mental_health-rps.pdf .

- 23.Sonar V. A retrospective study of prison deaths in western Maharashtra (2001-2008) Medico-Legal Update. 2010;10:112–4]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs Government of India; 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 23]. Bureau of Police Research and Development. Model prison manual for the superintendence and management of prisons in India. Available from: http://www.bprd.nic.in/writereaddata/linkimages/1445424768-Content%20%20 Chapters.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Human Rights Watch. New York: 1991. Human Rights Watch. Prison Conditions in India. [Google Scholar]