Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Although screening colonoscopy is effective in preventing distal colon cancers, effectiveness in preventing right-sided colon cancers is less clear. Previous studies have reported that retroflexion in the right colon improves adenoma detection. We aimed to determine whether a second withdrawal from the right colon in retroflexion vs. forward view alone leads to the detection of additional adenomas.

METHODS

Patients undergoing screening or surveillance colonoscopy were invited to participate in a parallel, randomized, controlled trial at two centers. After cecal intubation, the colonoscope was withdrawn to the hepatic flexure, all visualized polyps removed, and endoscopist confidence recorded on a 5-point Likert scale. Patients were randomized to a second exam of the proximal colon in forward (FV) or retroflexion view (RV), and adenoma detection rates (ADRs) compared. Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate predictors of identifying adenomas on the second withdrawal from the proximal colon.

RESULTS

A total of 850 patients (mean age 59.1±8.3 years, 59% female) were randomly assigned to FV (N=400) or RV (N=450). Retroflexion was successful in 93.5%. The ADR (46% FV and 47% RV) and numbers of adenomas per patient (0.9±1.4 FV and 1.1±2.1 RV) were similar (P=0.75 for both). At least one additional adenoma was detected on second withdrawal in similar proportions (10.5% FV and 7.5% RV, P=0.13). Predictors of identifying adenomas on the second withdrawal included older age (odds ratio (OR)=1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.01–1.08), adenomas seen on initial withdrawal (OR=2.8, 95% CI=1.7–4.7), and low endoscopist confidence in quality of first examination of the right colon (OR=4.8, 95% CI=1.9–12.1). There were no adverse events.

CONCLUSIONS

Retroflexion in the right colon can be safely achieved in the majority of patients undergoing colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. Reexamination of the right colon in either retroflexed or forward view yielded similar, incremental ADRs. A second exam of the right colon should be strongly considered in patients who have adenomas discovered in the right colon, particularly when endoscopist confidence in the quality of initial examination is low.

INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy is the gold standard screening test for colorectal neoplasia (1). Removal of adenomatous colon polyps during colonoscopy reduces colorectal cancer mortality by over 50% (2–4). However, although colonoscopy is highly effective at preventing distal (left sided) colon cancers, recent studies by Singh and others have demonstrated that colonoscopy provides limited protection from right-sided colon cancers (5–7). This difference has in large part been attributed to differences in tumor biology and polyp morphology in the proximal and distal colon (8,9). Specifically, proximal colon polyps are more often flat and thus more difficult to visualize compared with pedunculated polyps typically seen in the distal colon (10). In addition, proximal colon polyps are frequently located on the backs of haustral folds and on the inner curvatures of colonic flexures, which can make them more difficult to detect with a forward viewing colonoscope (11,12). Thus, there is currently great interest in developing techniques that may improve polyp detection in the proximal colon during colonoscopy.

A simple and straightforward method of improving the examination of the proximal colon is retroflexion during withdrawal of the colonoscopy (13). Retroflexion in the rectum has been a safe and effective method of improving neoplasia detection in the distal rectum (14,15). Although multiple groups have reported that retroflexion in the proximal colon can be safely performed, the impact of routine retroflexion in the proximal colon during screening colonoscopy is less clear (16–19). In the largest of these studies, Hewett and Rex observed that retroflexion in the proximal colon increased the detection of adenomas by 10% (17). However, the generalizability of this study is limited by the fact that only two expert endoscopists performed all procedures, with the implication that the increase in adenoma detection was related to endoscopist expertise and spending additional time examining the proximal colon. Indeed, tandem colonoscopy studies that involved examining the right colon twice in forward view have demonstrated that up to 27% of proximal colon adenomas are missed during routine screening colonoscopy performed by experienced gastroenterologists (20,21).

This study was undertaken to directly compare the yields of reexamining the right colon in retroflexion vs. forward view in a prospective manner during routine screening and surveillance colonoscopy.

METHODS

Consecutive adult patients (>18 years of age) undergoing outpatient colonoscopy by study investigators at the two study centers were invited to participate in this prospective randomized study. Patients were eligible if they were undergoing colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening or post-polypectomy surveillance. Patients were excluded if they were unable to provide informed consent, had prior resection of the right colon, inflammatory bowel disease, or the polyposis syndrome. In addition, patients were excluded if at the time of colonoscopy the cecum could not be intubated or if the quality of bowel preparation was inadequate (Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score <2 in any segment of the colon) (22,23). Patients were enrolled and baseline demographic characteristics were recorded before endoscopy by a research assistant or one of the investigators. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Washington University School of Medicine/Barnes Jewish Hospital (IRB# 201104076) and Medical College of Wisconsin (PRO00018945). The study was reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines and was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT01704820).

Procedures

All procedures were performed by one of the 10 attending gastroenterologists with or without the assistance of a gastroenterology fellow/surgical resident. Attending gastroenterologists had been in practice for a median of 12 years (range 1–32 years). Olympus variable stiffness colonoscopes (CF180/190 or PCF 180/190, Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA) were used for all procedures; the decision to use an adult or pediatric colonoscope was left to the discretion of the attending physician. Colonoscope insertion was performed in a standard manner. During scope insertion, the variable stiffness feature of the endoscope was used at the discretion of the attending gastroenterologist. After insertion into the base of the cecum, the scope was withdrawn to the level of the hepatic flexure as the mucosa was carefully inspected. All polyps that were found at that time were removed and sent for histopathologic examination. Once the proximal colon had been examined and polyps removed, the cecum was again intubated. At this point, a second examination of the proximal colon in one of the two randomly assigned groups, retroflexed view (RV) or standard forward view (FV), was performed. The endoscope was withdrawn to the level of the hepatic flexure in both arms, the mucosa was carefully examined, and all polyps were removed. Subjects randomized to the RV arm in whom retroflexion was not possible had a second examination of the right colon performed in forward view before evaluation of the more distal colon. After the second withdrawal to the hepatic flexure, the remainder of the colon was examined in forward view in a standard manner.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome variable of this study was the per-patient adenoma detection rate (ADR), calculated as the proportion of patients with at least one adenoma in each group. Secondary outcomes included the success rate of retroflexion, per patient polyp detection rate, per-polyp ADR (mean number of adenomas per patient), and duration of colonoscopy. Endoscopist comfort with retroflexion and confidence in the adequacy of the initial examination of the right colon were quantified using a 5-point Likert scale (1=very difficult, 5=very easy).

Sample size

On the basis of prior tandem colonoscopy studies, we expected a repeat exam of the right colon in forward view to identify additional adenomatous polyps in 7% of patients (4). Assuming a 12% ADR with a second exam of the right colon in retroflexion (5% increase in yield for additional polyps), 80% power, and a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, approximately 850 subjects would need to be randomized for this study.

Randomization

Simple randomization was used to allocate patients to the two groups (FV vs. RV). For the initial 393 subjects allocation was concealed until the start of the colonoscopy, and subjects with inadequate bowel preparation were excluded after randomization. In order to minimize patient drop out after randomization, the protocol was changed for the final 457 subjects and randomization was concealed until the cecum had been intubated and bowel preparation was deemed to be adequate.

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as mean±standard deviation for normally distributed data and median and range for skewed data. Grouped continuous data were compared using two-tailed Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test where appropriate. Intergroup and categorical comparisons were made using the Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Logistic regression analysis was utilized to evaluate predictors of adenoma detection and factors associated with successful retroflexion. Analysis of variance was utilized for comparison between endoscopists. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The primary analysis was performed in an intention-to-treat manner, and data were also re-analyzed in a per protocol manner. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Patients

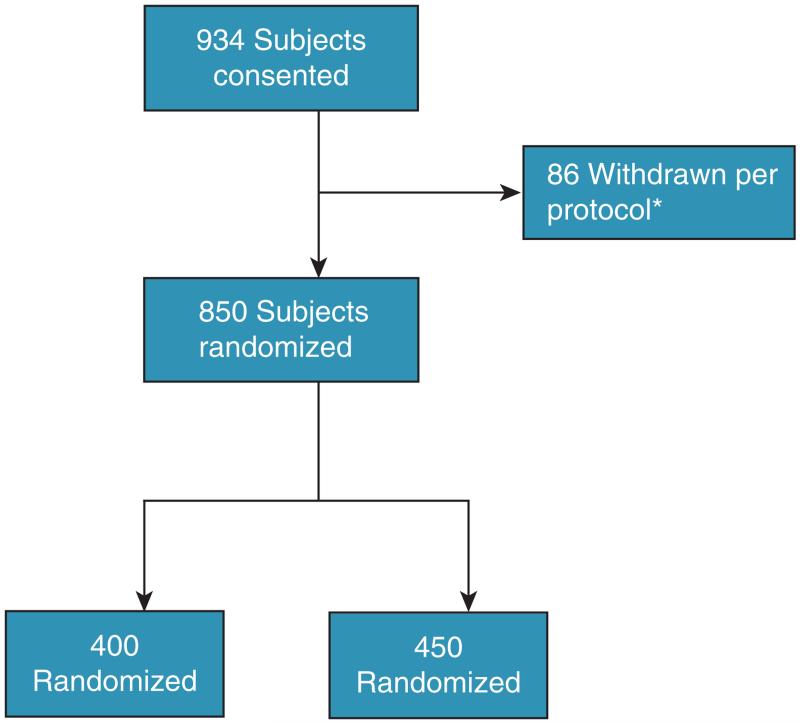

Nine hundred thirty-six consecutive patients were consented to participate in the study. Eighty-six patients (9.2%) were withdrawn from the study before randomization; the most common reason for excluding patients from the study was poor bowel preparation in 52 patients (Figure 1). Eight hundred fifty patients (mean age 59.1±8.3 years, 59% female) were randomized and included in the study. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Each endoscopist performed a median of 48 colonoscopies and had a median ADR of 46.8% (Table 2).

Figure 1.

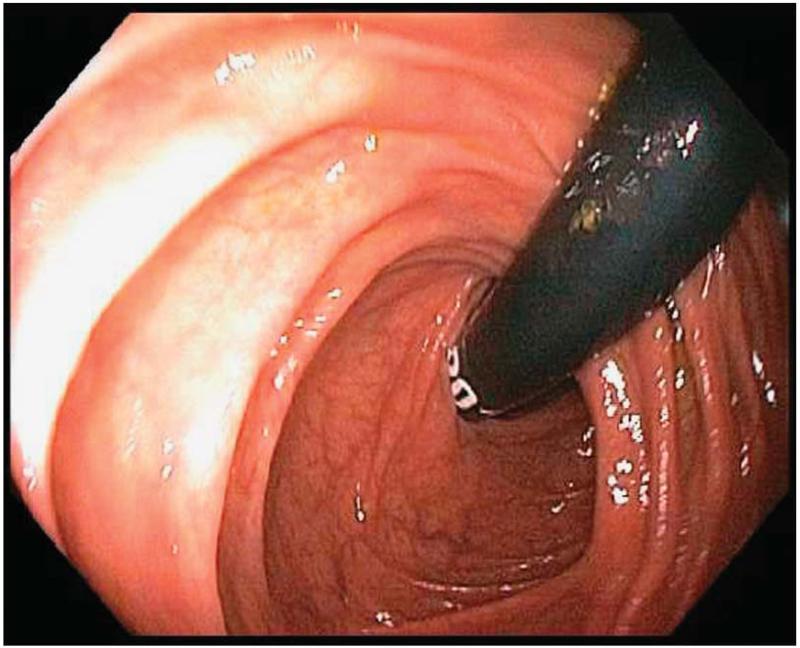

Retroflexion in right colon.

Table 1. Baseline demographics.

| Retroflexion (N=450) |

Forward view (N=400) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.9±8.3 | 59.0±8.3 | 0.94 |

| Female gender | 267 | 234 | 0.8 |

| BMI | 29.3±6.5 | 30.3±7 | 0.28 |

| Indication | 0.55 | ||

| Screening | 289 | 264 | |

| Surveillance | 161 | 136 | |

| Colon cancer in first degree relative |

71 | 64 | 0.93 |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 94 | 89 | 0.63 |

| Current smoker | 93 | 74 | 0.43 |

| Endoscope used | 0.19 | ||

| Pediatric | 410 | 347 | |

| Standard | 40 | 26 | |

| Quality of bowel preparation | 0.84 | ||

| BBPS 6 | 100 | 93 | |

| BBPS 7 | 61 | 47 | |

| BBPS 8 | 87 | 74 | |

| BBPS 9 | 202 | 186 | |

| Sedation | |||

| Monitored anesthesia carea | 359 | 319 | 0.99 |

| Conscious sedationb | 97 | 81 | |

| Prior abdominal surgery | 107 | 82 | 0.25 |

| Fellow involvement | 0.35 | ||

| Fellow present | 111 | 110 | |

| No fellow | 339 | 290 |

BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score; BMI, body mass index.

Monitored anesthesia care: deep sedation provided by an anesthesiologist.

Conscious sedation: moderate procedural sedation administered by a nurse under the direction of the endoscopist.

Table 2. Success in retroflexion by physician.

| Physician | P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD1 (N=422), % |

MD2 (N=123), % |

MD3 (N=71), % |

MD 4 (N=51), % |

MD 5 (N=57), % |

MD 6 (N=45), % |

MD 7 (N=22), % |

MD 8 (N=13), % |

MD 9 (N=32), % |

MD 10 (N=14), % |

||

| Successful retroflexion | 95.6 | 65.4 | 80.7 | 81.5 | 100 | 88.9 | 95.5 | 100 | 75 | 82.4 | 0.054 |

| Right ADR exam 2 | 12.6 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 15.7 | 21.4 | 5.3 | 20 | 22.7 | 38.5 | 18.8 | 0.006 |

| Overall ADR | 48.1 | 44.7 | 36.6 | 41.2 | 71.4 | 36.8 | 51.1 | 45.5 | 76.9 | 53.1 | 0.08 |

ADR, adenoma detection rate.

Retroflexion in proximal colon

Retroflexion of the endoscope in the proximal colon was successfully performed in 421 of 450 (93.5%) subjects randomized to the RV arm of the study. In the 29 cases where retroflexion in the proximal colon was not successful, the reasons for failure were excessive looping (25), restricted mobility of the colon (3), and intraprocedural equipment malfunction (1). Success of retroflexion did not appear to be physician dependent (Table 2, P=0.054 across groups). When retroflexion was possible, the attending endoscopist felt it was very easy in 318 (70.7%) cases, easy in 71 (15.8%), somewhat difficult in 25 (5.6%), difficult in 5 (1.1%), and very difficult in 21 (5%). On logistic regression analysis, the only factor significantly associated with failure to retroflex in the right colon was poor bowel preparation quality (Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score 6 vs. ≥7; P=0.012; Table 3).

Table 3. Predictors of unsuccessful retroflexion.

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.126 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Reference | |

| Female | 1.6 (0.69–3.53) | 0.280 |

| BMI | 1.03 (0.97–1.1) | 0.371 |

| Fellow involvement | ||

| Fellow present | Reference | |

| No fellow | 3.2 (0.99–10.2) | 0.051 |

| Abdominal surgery | ||

| None | ||

| Prior abdominal surgery | 2.1 (0.88–4.96) | 0.097 |

| Endoscope used | ||

| Standard | Reference | |

| Pediatric | 1.5 (0.5–4.8) | 0.53 |

| Sedation | ||

| Monitored anesthesia care | Reference | |

| Conscious sedation | 2.3 (0.9–5.9) | 0.078 |

| Diabetes | 1.2 (0.47–2.94) | 0.722 |

| Total BBPS | ||

| BBPS 9 | Reference | |

| BBPS 6 | 3.1 (1.3–7.6) | 0.012 |

| BBPS 7 | 0.24 (0.03–2 | 0.187 |

| BBPS 8 | 0.57 (0.15–2.2) | 0.411 |

BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Colonoscopy findings

On initial evaluation of the proximal colon there were an average of 0.39 and 0.37 adenomas found per patient in the RV and FV groups, respectively (P=0.71; Table 4). Endoscopist confidence in the quality of the initial exam of the proximal colon was similar in the two groups (P=0.31). On intention-to-treat analysis, repeat examination of the proximal colon yielded similar results in the two groups, with an average of 0.09 and 0.12 adenomas found per patient in the RV and FV groups, respectively (P=0.13). Furthermore, the overall ADR did not differ between the two groups (46% (184/400) FV and 47% (212/450) RV, P=0.75)) or did the average number of adenomas per patient (0.9 FV and 1.1 RV, P=0.75). There was one adenocarcinoma discovered in the study population during initial examination of the ascending colon.

Table 4. Colonoscopy findings.

| Retroflexion (N=450) |

Forward view (N=400) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in quality of initial examination of proximal colon | 0.31 | ||

| Very high | 349 | 293 | |

| High | 84 | 95 | |

| Moderate | 16 | 11 | |

| Low | 1 | 1 | |

| Very low | 0 | 0 | |

| Withdrawal 1 | |||

| Duration | 2.8±3.1 | 2.8±2.5 | 0.89 |

| ≥1 Polyp | 133 | 120 | 0.89 |

| ≥1 Adenoma | 102 | 94 | 0.78 |

| Polyps per patient | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.78 |

| Adenomas per patient | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.71 |

| Withdrawal 2 | |||

| Duration | 1.4±1.3 | 1.9±1.8 | <0.001 |

| ≥1 Polyp | 48 | 58 | 0.09 |

| ≥1 Adenoma | 34 | 42 | 0.13 |

| Polyps per patient | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.1 |

| Adenomas per patient | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Distal colon | |||

| Duration | 8.3±5.9 | 8.0±5.4 | 0.53 |

| ≥1 Polyp | 232 | 201 | 0.73 |

| ≥1 Adenoma | 150 | 115 | 0.16 |

| Polyps per patient | 1.1 | 0.98 | 0.48 |

| Adenomas per patient | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.1 |

| Total | |||

| Duration | 22.0±10.9 | 21.1±9.7 | 0.23 |

| ≥1 Polyp | 281 | 257 | 0.62 |

| ≥1 Adenoma | 212 | 184 | 0.75 |

| Polyps per patient | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.89 |

| Adenomas per patient | 1.1 | 0.93 | 0.75 |

The per-polyp miss rates of the initial examination of the proximal colon were 20.3% (56/276) in the RV and 27.0% (66/244) in the FV group (P=0.08). There was a statistically significant difference in the duration of second withdrawal from the right colon between the RV and FV groups (1.4 min vs. 1.9 min, P<0.001); however, the overall withdrawal time was similar in the two groups (12.5 min in RV and 12.7 min in FV, P=0.7). The median size of polyps found on repeat examination of the proximal colon was 5 mm (range 2–15) in the RV and 5 mm (2–21) in the FV groups (P=0.87). Advanced adenomas were found in 10 patients during repeat examination of the proximal colon (5 in each group); all were >10 mm in size. Adenomas were detected on the second examination in 48 (10.7%) patients in the RV arm and 58 (14.5%) in the FV arm (P=0.1). Sixteen (7 RV and 9 FV group; P=0.43) patients had adenomas identified only on the second examination of the proximal colon; the median size was 5 mm (range 3–10). Overall, surveillance recommendations were altered on the basis of the results of the second examination of the proximal colon in 23 (2.7%) cases; reasons for alteration in surveillance recommendations are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Patients in whom reexamination of the proximal colon led to change in surveillance recommendations.

| Retroflexion | Forward view | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoma detected only on 2nd exam |

5 | 5 | |

| Advanced adenoma only on 2nd exam |

5 | 5 | |

| 3rd Adenoma found | 0 | 3 | |

| Total | 10 | 13 | 0.43 |

On logistic regression, significant predictors of identifying at least one adenoma on the second withdrawal from the right colon were older age (odds ratio (OR)=1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.01–1.08), adenomas seen on initial withdrawal (OR=2.8, 95% CI=1.7–4.7), and low endoscopist confidence in the quality of first examination of the right colon (OR=4.8, 95% CI=1.9–12.1; Table 6).

Table 6. Predictors of identifying adenomas on reexamination of the proximal colon.

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.014 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Reference | |

| Male | 1.4(0.72–2.3) | 0.240 |

| BMI | 1.03 (0.97–1.1) | 0.371 |

| Family history of colon cancer | 0.72 (0.4–1.5) | 0.380 |

| Indication | ||

| Screening | Reference | |

| Surveillance | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 0.120 |

| Adenoma(s) found on initial exam of proximal colon |

2.8 (1.6–4.9) | <0.001 |

| Duration of initial exam of proximal colon |

1.0 (0.93–1.1) | 0.900 |

| Confidence in quality of initial exam of proximal colon | ||

| Very high or high | Reference | |

| Moderate or low | 4.3 (1.7–11.1) | 0.002 |

| Mode of second exam | ||

| Forward view | Reference | |

| Retroflexion | 0.63 (0.38–1.1) | 0.068 |

| Fellow involvement | ||

| Fellow present | Reference | |

| No fellow | 1.5 (0.81–3.0) | 0.190 |

| Abdominal surgery | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Prior abdominal surgery | 0.56 (0.28–1.1) | 0.090 |

| Sedation | ||

| Conscious sedation | Reference | |

| Monitored anesthesia care | 1.6 (0.74–3.3) | 0.240 |

| Diabetes | 1.1 (0.58–1.98) | 0.820 |

| BBPS right colon | ||

| BBPS 2 | Reference | |

| BBPS 3 | 0.74 (0.44–1.2) | 0.250 |

BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Per protocol analysis

When data were analyzed in a per protocol manner (421 subjects in whom retroflexion was successful vs. 429 subjects in whom the colon was inspected twice in forward view), repeat examination of the proximal colon yielded similar results in the two groups, with an average of 0.09 and 0.12 adenomas being found per patient in the RV and FV groups, respectively (P=0.58). The overall adenoma detection did not differ between the two groups (46% FV and 47% RV, P=0.79) or did the average number of adenomas per patient (0.96 FV and 1.1 RV, P=0.8). Predictors of identifying adenoma(s) on the second withdrawal from the right colon were older age (OR=1.04, 95% CI=1.01–1.08), adenomas seen on initial withdrawal (OR=2.8, 95% CI=1.6–4.9), and low endoscopist confidence in the quality of first examination of the right colon (OR=3.9, 95% CI=1.6–10.1).

Adverse events

There were no adverse events during the colonoscopies or immediate post procedure recovery. Follow-up for delayed complications was not performed.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter randomized controlled trial, we found that retroflexion in the right colon can be successfully and safely performed in 94% of patients undergoing colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening using standard colonoscopes. There was no significant difference in adenoma miss rates when the proximal colon was reexamined in forward view vs. retroflexion. What was striking in this study is that there was a 20% miss rate in finding adenomas in the right colon; however, these missed polyps could be found at similar rates if the right colon was examined a second time, regardless of whether forward view or retroflexed examination was performed. We report that older age, presence of right-sided adenomas, and poor endoscopist confidence in the first examination are predictors of finding additional polyps in the right colon.

The only prior randomized study evaluating the effect of proximal colon retroflexion on ADR was published by Harrison et al. (16) This study also showed no significant differences in adenoma miss rates in 98 patients between a second examination from the cecum to splenic flexure in forward vs. retroflexed views by a single experienced endoscopist after examination of the same sections of colon first in forward view by two experienced fellows. Our study expands upon these findings, by including larger numbers of patients, more endoscopists with varying degrees of experience, and a more homogeneous cohort of patients undergoing only screening or surveillance colonoscopies. In addition, we identified potential factors that were associated with finding at least one missed adenoma during a second examination of the right colon (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow of patients through study. *52 Inadequate bowel preparation, 20 colonoscopy performed by non-investigator because of schedule change, 6 prior right colon resection, 2 colonoscopy aborted because of medical instability, 1 inability to reach cecum, 1 patient withdrew consent, 1 newly diagnosed with colitis, 1 >100 polyps and familial adenomatous polyposis was suspected.

The failure of proximal colon retroflexion to yield a higher adenoma miss rate compared with a second examination of the proximal colon in forward view reinforces the fact that right colon adenomas are not always missed because of the location of the lesion relative to the view angle of the endosocpe (13). In randomized tandem colonoscopy studies utilizing the Third Eye Retroscope (Avantis Medical Systems, Sunnyvale, CA), which allows for retrograde views of the colon from an auxillary device passed into the working channel of the colonoscope, increases in ADR by up to 23% have been reported (4). Similarly, the use of the full-spectrum endoscopy colonoscope, which proves a 330° view angle (vs. 170° view angle of a standard colonoscope), led to a 43% increase in adenoma detection in a recent prospective study (24). However, tandem colonoscopy studies, in which the proximal colon was examined twice in forward view, have also demonstrated increases in ADR, which are on par with those seen in our study and with the Third Eye and full-spectrum endoscopy systems (20,25). We hypothesize that the lack of advantage to retroflexion in the right colon vs. a second forward examination may be due to the fact that during retroflexion only some portions of the colon mucosa are visualized. This could negate any benefit of retroflexion compared with additional missed adenomas found that would have been found during a second forward view. As the configuration of folds and distension of the right colon changes between examinations, additional polyps are brought into view regardless of the direction of the examination. Likewise, the view angle of the scope does not improve the endoscopist’s ability to visualize flat and indistinct polyps, such as sessile serrated adenomas. Finally, we did observe that the duration of the second withdrawal was significantly shorter in the retroflexion group, but the underlying factors for this difference are unclear.

We also found that a second examination of the right colon in either view was more likely to detect missed adenomas in patients who have polyps suspected to be adenomas on initial examination of the right colon or are older in age, especially when the endoscopist’s confidence in the quality of initial right colon examination was low. The latter was the strongest predictor of identifying missed adenomas with a second examination of the right colon. This may be related to suboptimal visualization of the mucosa related to bowel preparation and/or anatomic issues that preclude smooth withdrawal of the colonoscope. It is important to note that missed adenomas occurred in a fifth of the patients with right-sided adenomas, which indicates that right-sided adenomas are not easy to identify on a single examination. The finding that adenomas in the right colon tended to be missed if at least one adenoma was found on initial withdrawal supports that colon neoplasia is a field defect and that the finding of at least one adenoma in the right colon should increase the endoscopist’s vigilance in finding additional adenomas (26). The presence of any of these factors should warrant consideration of a repeat examination of the right colon for missed adenomas.

The prior literature on the feasibility and safety of retroflexion in the proximal colon has been limited to the experiences of only highly skilled endoscopists (13,16,17). In the present study, involving ten endoscopists with varying levels of experience, retroflexion was successful in 94% of patients, which was identical to what was reported by Hewett and Rex (17). The experience of our group as well as others suggests that retroflexion in the proximal colon can be a useful maneuver when evaluating and removing polyps in the right colon (16,18,27,28). There were no complications associated with this maneuver, and our results suggest that retroflexion can be safely performed during routine colonoscopy when clinically indicated. However, the negative results of this study as well as prior reports by others suggest that retroflexion in the right colon should not be adopted as a routine maneuver during screening or surveillance colonoscopy.

This study has limitations. First, it was conducted at two academic medical centers, and therefore the results may not be applicable to the community setting. However, we believe this limitation is mitigated by that the participation of 10 endoscopists with a wide range of prior experience. As well, we found no significant variation in the success rate of retroflexion among physicians. Second, the same endoscopist performed back to back examinations of the proximal colon, which would not account for factors such as individual endoscopist’s ADRs that could have potentially affected the adenoma miss rate. Although having a different endoscopist performing the second examination of the right colon would have addressed this issue, having the same endoscopist perform both examinations of the right colon more closely replicates real world clinical practice and increases the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, we found that a second examination of the right colon leads to increased adenoma detection; however, reexamination in retroflexion is not superior to a second exam in forward view. Moreover, retroflexion in the proximal colon could be accomplished safely in a vast majority of patients using standard colonoscopes. We also found that missed proximal colon adenomas were associated with a subjective impression of a poor quality initial examination of the right colon and finding adenomas on the initial examination of the proximal colon. Thus, reexamination of the right colon in forward view or retroflexion should be considered in particular with a subjective impression of a poor quality right colon initial examination or when polyps suspected of being adenomatous are found on first withdrawal from the right colon.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

-

✔

Colonoscopy may be less effective in preventing right-sided colon cancers, and moreover right-sided colon polyps are missed more frequently compared with left-sided polyps.

-

✔

Retroflexion of the colonoscope in the right colon may allow for improved visualization of the mucosa, but it remains to be determined whether retroflexion in the right colon improved adenoma detection rates.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

-

✔

Retroflexion in the right colon can be safely achieved in the majority of patients undergoing colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening.

-

✔

In this randomized controlled trial, we found that reexamination of the right colon in either retroflexed or forward view yielded similar, incremental adenoma detection rates.

-

✔

A second exam of the right colon should be strongly considered in patients who have adenomas discovered in the right colon, particularly when endoscopist confidence in the quality of initial examination is low.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: None.

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Dayna S. Early, MD.

Specific author contributions: Dayna S. Early, Vladimir M. Kushnir, and Gregory S. Sayuk: study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Chien-Huan Chen, Nicholas Davidson, Daniel Mullady, Faris M. Murad, Noura M. Sharabash, Eric Ruettgers, Themistocles Dassopoulos, Jeffrey J. Easler, C. Prakash Gyawali, and Steven A. Edmundowicz: data collection and manuscript preparation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Trends in colorectal cancer incidence rates in the United States by tumor location and stage, 1992–2008. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:411–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. Colonoscopic polypectomy and the incidence of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2001;48:753–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leufkens AM, DeMarco DC, Rastogi A, et al. Effect of a retrograde-viewing device on adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy: the TERRACE study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:480–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh H, Nugent Z, Mahmud SM, et al. Predictors of colorectal cancer after negative colonoscopy: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:663–73. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.650. quiz 674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, et al. Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy: a population-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:22–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Sanderson AK, 2nd, et al. Likelihood of missed and recurrent adenomas in the proximal versus the distal colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzoni C, Bottarelli L, Campanini N, et al. Distinct molecular patterns based on proximal and distal sporadic colorectal cancer: arguments for different mechanisms in the tumorigenesis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:115–26. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T, Rouse RV, et al. Prevalence of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic and symptomatic adults. JAMA. 2008;299:1027–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg DS. Colonoscopy: what does it take to get it “right”? Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:68–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Gupta R, et al. Diagnostic yield and therapeutic impact of single-balloon enteroscopy: Series of 106 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1631–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teshima CW, Mensink PB. Small-bowel endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2011;43:38–41. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waye JD. Retroview colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varadarajulu S, Ramsey WH. Utility of retroflexion in lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:235–7. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanson JM, Atkin WS, Cunliffe WJ, et al. Rectal retroflexion: an essential part of lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1706–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02234394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison M, Singh N, Rex DK. Impact of proximal colon retroflexion on adenoma miss rates. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:519–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewett DG, Rex DK. Miss rate of right-sided colon examination during colonoscopy defined by retroflexion: an observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rex DK, Khashab M. Colonoscopic polypectomy in retroflexion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pishvaian AC, Al-Kawas FH. Retroflexion in the colon: a useful and safe technique in the evaluation and resection of sessile polyps during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1479–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG, et al. Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy. 2008;40:284–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, et al. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calderwood AH, Schroy PC, 3rd, Lieberman DA, et al. Boston Bowel Preparation Scale scores provide a standardized definition of adequate for describing bowel cleanliness. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, et al. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gralnek IM, Siersema PD, Halpern Z, et al. Standard forward-viewing colonoscopy versus full-spectrum endoscopy: an international, multicentre, randomised, tandem colonoscopy trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:353–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, et al. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backman V, Roy HK. Advances in biophotonics detection of field carcinogenesis for colon cancer risk stratification. J Cancer. 2013;4:251–61. doi: 10.7150/jca.5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurlstone DP, Sanders DS, Thomson M, et al. ‘Salvage’ endoscopic mucosal resection in the colon using a retroflexion gastroscope dissection technique: a prospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:902–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coumaros D, Tsesmeli N. Retroflexion-assisted EMR in the colon with immediate closure of a procedure-related perforation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1332–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]