Abstract

Objectives

Adult literature supports the elimination of mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) for elective colorectal surgical procedures. Prospective data for the pediatric population regarding the utility of MBP is lacking. The primary aim of this study was to compare infectious complications, specifically anastomotic leak, intraabdominal abscess, and wound infection in patients who received MBP to those who did not.

Methods

A randomized pilot study comparing MBP with polyethylene glycol to no MBP was performed. Patients 0–21 years old undergoing elective colorectal surgery were eligible, and were randomized within 4 age strata. Statistical analyses was performed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and t-test or Wilcoxon two-sample test for continuous data.

Results

Forty-four patients were enrolled in the study from December 2010 to February 2013, of which 24 (55%) received MBP and 20 (45%) did not. Two patients (5%) had anastomotic leak, 4 (9%) had intraabdominal infection, and 7 (16%) had wound infections. The rate of anastomotic leak, intraabdominal abscess, and wound infection did not differ between the two groups.

Conclusion

Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery in children does not affect the incidence of infectious complications. A larger multi-institutional study is necessary to validate the results of this single-institution pilot study.

Keywords: Bowel preparation, colorectal surgery, pediatric

Introduction

Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) prior to elective colorectal surgery has been the standard surgical practice for decades. Recent adult data, including the results of several meta-analyses have questioned the benefit of this practice [1–6]. In the pediatric population, minimal data regarding MBP exists with only a few retrospective reports questioning its utility and benefit [7–9]. MBP in pediatric patients is typically performed in an inpatient setting, and delivered via a nasogastric tube, resulting in an additional expense for preoperative admission, and additional patient discomfort. Despite the existing adult and pediatric data, 96% of practicing pediatric surgeons still use MBP in their clinical practice, according to a recent survey [10].

Given the lack of prospective pediatric data, we conducted a single institution randomized pilot study to evaluate the role of MBP in pediatric patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. The primary aim of this study was to compare infectious complications, specifically anastomotic leak, intraabdominal abscess, and wound infection in patients who received MBP to those who did not.

Materials and Methods

Following the approval of the institutional review board at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, an unblinded randomized pilot study was performed, comparing the infectious complications of those who received a MBP with polyethylene glycol to those who did not. Patient eligibility included age between 0 and 21 years, an elective surgical procedure involving the colon and/or rectum, parental consent, and patient assent for those age 9 years and older.

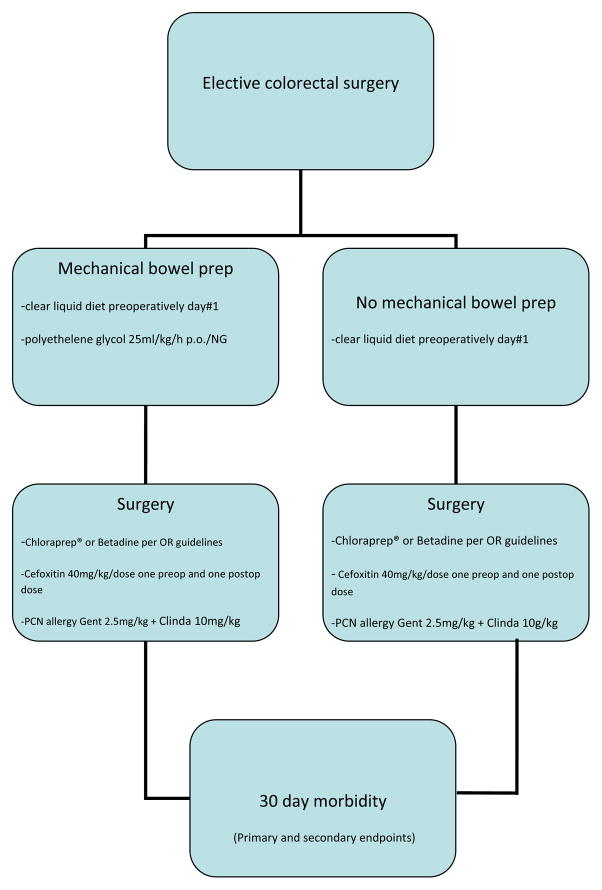

Patients were randomized to receive either mechanical bowel preparation with 25ml/kg/h of polyethylene glycol administered orally or via a nasogastric tube, plus clear liquid diet as tolerated, or a clear liquid diet alone (Figure 1). Both groups were kept nil per os beginning at midnight prior to the procedure. Patients randomized to receive a MBP were admitted to the hospital the day prior to surgery, while those who did not receive the MBP were admitted at the conclusion of the surgical procedure. Neither group received oral antibiotics as part of the bowel preparation. Both groups received one preoperative dose of intravenous cefoxitin 40mg/kg, up to 2g administered 0–30 minutes prior to skin incision, and one postoperative dose administered 8 hours from the first dose. For patients with penicillin or cephalosporin allergies, gentamicin 2.5mg/kg and clindamycin 10mg/kg were administered at equivalent time points. Ostomy or rectal irrigations if desired were carried out at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Surgical skin preparation was performed with either Betadine or 2% chlorhexidine gluconate/70%isopropyl alcohol (ChloraPrep®, CareFusion Dublin, Ohio, USA) according to our institutional operating room guidelines. These guidelines require 2% chlorhexidine gluconate/70% isopropyl alcohol solution skin preparation for all cases except in patients less than 3 months of age, or if the area of preparation requires the incorporation of mucosal surfaces, in which case a Betadine skin preparation is then utilized.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of study protocol.

Baseline demographic data collected included age, sex, diagnosis, procedure being performed, presence of steroids, presence of chronic or recent antibiotic use, and other medications. Primary endpoint data collected included the development of an intraabdominal infection, anastomotic leak, or wound infection. In hospital data collected for secondary endpoints included operative time, method of wound closure, hospital length of stay (LOS), time to removal of the nasogastric tube (NGT), time to first stool, time to full enteral feeds, the development of any infection other than that listed as a primary endpoint, antibiotic therapy outside of the protocol, and fascial dehiscence. Follow up data were collected up to 30 days from the date of surgery.

This was a single-institution pilot study. Randomization was performed by an independent person (staff secretary), ensuring investigator masking. A fixed allocation procedure was used, in which the probability of allocation to either control or experimental group is each 0.5. A permuted block randomization scheme was used, in which the blocking factor varied randomly between 4 and 6. The randomization schemes were used within 4 age strata: infants (<1 year), toddlers (1–5 years), older children (6–12 years), adolescents (13–21 years). Such a scheme allowed eligible patient to be randomized, without necessarily allocating equivalent numbers of patients to each stratum. Statistical analyses was performed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and t-test or Wilcoxon two-sample test for continuous data.

Results

Forty-four patients were enrolled in the study from December 2010 to February 2013. Twenty-four patients (55%) received MBP and 20 (45%) did not. Baseline demographics did not differ between the groups. The mean age of the patients was 7.3 years (SD +/− 6.6 years, median 6 years). Per defined age strata, there were 14 patients (32%) less than age 1 year, 7 patients (16%) between 1–5 years, 7 patients (16%) between 6–12 years, and 16 patients (36%) between 13–21 years. Patient disease distribution included twelve patients with ulcerative colitis, 7 patients with Crohn’s disease, 7 patients with Hirschsprung’s disease, 10 patients with imperforate anus, and 8 patients with other diagnoses (colostomy closure for sigmoid volvulus (n=1), resection of rectal duplication cyst (n=1), re-establishment of intestinal continuity with history of necrotizing enterocolitis (n=2), stoma closure for distal ileal atresia (n=1), colonic dysmotility/pseudoobstruction (n=3). Nine of the 44 patients (20%) had diverting stomas created at the time of the surgical procedure. Of those with imperforate anus, 6 underwent colostomy closure and 4 underwent posterior sagittal anorectoplasty without diverting stomas.

Two patients (5%) had anastomotic leak, 4 (9%) had intraabdominal infection, and 7 (16%) had wound infections. The rate of anastomotic leak, intraabdominal abscess, and wound infection did not differ between those who received a MBP and those who did not (Table 1). Five patients required either a re-operation or a procedure for infectious complications: 3 patients required diverting stomas for pelvic anastomotic leak (2) or perineal wound dehiscence (1), 1 patient required application of a wound vacuum device for a wound infection, and 1 patient required placement of a transrectal drain by interventional radiology for a pelvic abscess. There was no significant difference between the groups in length of NGT, overall LOS, time to first stool, time to full enteral feeds, and operative time (Table 2). There were no cases of fascial dehiscence, one case of gastrointestinal bleeding in the MBP group, and no mortality. Method of wound closure (primary versus interrupted/loose closure) did not affect the incidence of wound infection (p=0.127). There were no significant differences between patients with a diverting stoma and those with an inline fecal stream in the primary variables. However, compared to patients with an inline fecal stream, patients with a diverting stoma did have a longer length of stay (9.9 +/−3.0 days vs 8.6 +/− 10 days; p=0.012), longer time to achieve full enteral feeds (6.7 +/− 2.1 days vs 5.5 +/− 4.1 days; p=0.02), and longer operative time (209 +/− 71 minutes vs 137 +/− 89 minutes; p=0.006).

Table 1.

Primary endpoints comparing those who received a MBP and those who did not.

| Primary Variable | Category | Total | with Bowel Prep % (n) | without Bowel Prep % (n) | p-value (2 sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastomotic leak | N | 42 | 54.8 (23) | 45.2 (19) | 1.0 |

| Y | 2 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | ||

| Intraabdominal infection | N | 40 | 52.5 (21) | 47.5 (19) | 0.6137 |

| Y | 4 | 75 (3) | 25 (1) | ||

| Wound Infection | N | 37 | 51.4 (19) | 48.6 (18) | 0.4280 |

| Y | 7 | 71.4 (5) | 28.6 (2) |

Table 2.

Secondary endpoints comparing those who received a MBP and those who did not.

| Secondary Variable | With Bowel Prep Mean (SD) | Without Bowel Prep Mean (SD) | P-value (2 sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS (d) | 8.42 (4.84) | 9.39 (13.12) | 0.4242 |

| Time to 1st stool (d) | 2.92 (1.61) | 3.60 (1.57) | 0.1458 |

| Time to full enteral feeds (d) | 5.17 (2.66) | 6.40 (4.89) | 0.3937 |

| Length of NGT (d) | 4.63 (2.50) | 5.00 (3.39) | 0.8011 |

| Operative time (min) | 143.96 (74.90) | 161.70 (105.35) | 0.524 |

Postoperative compliance with the antibiotic protocol was challenging to maintain. Standard protocol antibiotic regimen (2 doses intravenous cefoxitin 40mg/kg/dose or 1–2g per dose) was adjusted as deemed appropriate by the operating surgeon in 39% of patients, 75% with MBP and 45% without MBP (p=0.041). This “noncompliance” with the standard regimen was represented by either additional postoperative doses of cefoxitin, or by the use of an alternate broad-spectrum antibiotic. Two patients with inflammatory bowel disease were on preoperative antibiotics which were continued postoperatively. Despite this, there was no significant difference in anastomotic leak, intraabdominal infection, or wound infection rates between those who received the standard protocol antibiotic regimen compared to those who did not (Table 3). When analyzing the antibiotic protocol deviations separately for those who received a MBP and for those who did not, we found no significant differences found for the primary variables (Table 4a and 4b). Other infections occurred in 6 cases, and included 2 cases of yeast/diaper rash, 2 cases of pneumonia diagnosed by fever and CXR findings, and 2 cases of superficial thrombophlebitis related to an indwelling peripheral intravenous catheter. Two of these patients received MBP and 4 did not; 2 received appropriate protocol antibiotics and 4 did not. The two patients with yeast/diaper rash had received additional doses than the antibiotic regimen outlined in the protocol.

Table 3.

Primary endpoints comparing those who received perioperative intravenous antibiotics according to the study protocol and those who did not.

| Primary Variable | Category | Total | With protocol antibiotics combined groups % (n) | Without protocol antibiotics combined groups % (n) | p-value (2 sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastomotic leak | N | 42 | 61.9 (26) | 38.1 (16) | 1.0 |

| Y | 2 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | ||

| Intraabdominal infection | N | 40 | 60 (24) | 40 (16) | 1.0 |

| Y | 4 | 75 (3) | 25 (1) | ||

| Wound Infection | N | 37 | 59.5 (22) | 40.5 (15) | 0.6886 |

| y | 7 | 71.4 (5) | 28.6 (2) |

Table 4.

Primary endpoints comparing those who received perioperative intravenous antibiotics according to the study protocol, among patients who received a MBP (a) and those who did not receive a MBP (b).

| Table 4a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Variable | Category | Total | With protocol antibiotics MBP % (n) | Without protocol antibiotics MBP % (n) | p-value (2 sided) |

| Anastomotic leak | N | 23 | 100 (18) | 83.3 (5) | 0.25 |

| Y | 1 | 0 (0) | 16.7 (1) | ||

| Intraabdominal infection | N | 21 | 88.9 (16) | 83.3 (5) | 1.0 |

| Y | 3 | 11.1 (2) | 16.7 (1) | ||

| Wound Infection | N | 19 | 77.8 (14) | 83.3 (5) | 1.0 |

| Y | 5 | 22.2 (4) | 16.7 (1) | ||

| Table 4b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Variable | Category | Total | With protocol antibiotics Without MBP % (n) | Without protocol antibiotics Without MBP % (n) | p-value (2 sided) |

| Anastomotic leak | N | 19 | 88.9 (8) | 100 (11) | 0.45 |

| Y | 1 | 11.1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Intraabdominal infection | N | 19 | 88.9 (8) | 100 (11) | 0.45 |

| Y | 1 | 11.1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Wound Infection | N | 18 | 88.9 (8) | 90.9 (10) | 1.0 |

| Y | 2 | 11.1 (1) | 9.1 (1) | ||

Subgroup analysis by age stratification and disease group did not reveal any significant differences in the primary or secondary endpoints.

Discussion

Mechanical bowel preparation has been the mainstay of colorectal surgery practice for decades. Recent adult data has questioned the utility of this practice, with some reports suggesting an increase in complications, including anastomotic leak, wound infection, and other postoperative morbidity in those who receive a MBP [1–6,11–15]. Whether this data is applicable to children as well is unclear, as the few current pediatric reports are either retrospective or observational in nature [7,8,10]. In addition, MBP in children carries an increased morbidity, often requiring the expense of an additional hospital day, the placement of a nasogastric tube for administration of the preparation, and additional laboratory tests and intravenous fluids to ensure adequate hydration during the preparation.

Given this data and the current existing practice of 96% of current pediatric surgeons [10], we designed a single institution randomized controlled study comparing the incidence of wound infection, intraabdominal infection, and anastomotic leak between those who received a MBP consisting of polyethylene glycol and those who did not. We found no significant differences between the two groups for these primary endpoints. We also found no differences in LOS, time to first stool, length of time NGT was in place, time to enteral feeds, and incidence of other infections.

While this is the only prospective study evaluating this question in pediatric patients, we acknowledge several limitations. First, we recognize that this study is underpowered. Initial statistical calculations proposed 906 experimental patients and 906 control patients in order to detect a statistically significant difference with 80% power. This is not feasible outside the context of a multicenter study, and so our goal was to perform this pilot study to obtain preliminary data that would support such a study. We were also limited by several staff surgeon’s lack of agreement to allow enrollment of their patients, thereby limiting the accrual of subjects. We had hoped that the strength of prior data casting uncertainty on the need for MBP in adult patients would create sufficient equipoise to encourage greater participation. However, our experience demonstrates the much lamented difficulty in recruiting pediatric surgical patients for randomized studies [16,17]. Perhaps the data from this pediatric-specific pilot study will reduce the barriers toward accrual of subjects for a similar study in the future. Second, we recognize the heterogeneous population that comprised this study group. By stratifying the randomization by age group, we attempted to minimize one variable of heterogeneity. We also performed a subgroup analysis among the various diagnoses, which did not reveal any differences in our primary endpoints. The third limitation to this study was the escalation of the proposed perioperative intravenous antibiotic regimen in 39% of patients, with 61% of patients receiving the appropriate number of doses and correct drug outlined by the protocol. This was generally attributed to a higher degree of concern by the operating surgeon prompting additional antibiotic doses. The purpose of the study was not to interfere with the perioperative management by the surgeon of record, and so we chose to continue to include patients despite protocol violation on an intention to treat basis. Despite the high rate of noncompliance with the postoperative antibiotic regimen, however, we identified no significant differences in our primary endpoints between the group who received appropriate protocol intravenous antibiotics and those who did not.

Additional areas of potential investigation that were not addressed in this current study include postoperative pain and its relationship to receiving a mechanical bowel preparation, and differences between patients who given the bowel preparation orally compared to those who required a nasogastric tube for administration.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report the first prospective, randomized study to evaluate the use of MBP in pediatric patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. We identified no significant differences in anastomotic leak, intraabdominal infection, or wound infection between those who received a MBP and those who did not, corroborating literature reported in the adult population. While these data are encouraging, more robust evidence to determine whether MBP can be safely omitted in children undergoing elective colorectal procedures will require a prospective, randomized, multicenter study.

Acknowledgments

This study was in part funded by a grant from Clinical and Translational Science Awards (UL1TR000090).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Pineda CE, Shelton AA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation in intestinal surgery: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2037–2044. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slim K, Vicaut E, Panis Y, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of colorectal surgery with or without mechanical bowel preparation. The British journal of surgery. 2004;91:1125–1130. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guenaga KK, Matos D, Wille-Jorgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2009:CD001544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu QD, Zhang QY, Zeng QQ, et al. Efficacy of mechanical bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol in prevention of postoperative complications in elective colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:267–275. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0834-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slim K, Vicaut E, Launay-Savary MV, et al. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on the role of mechanical bowel preparation before colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2009;249:203–209. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318193425a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wille-Jorgensen P, Guenaga KF, Matos D, et al. Pre-operative mechanical bowel cleansing or not? an updated meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leys CM, Austin MT, Pietsch JB, et al. Elective intestinal operations in infants and children without mechanical bowel preparation: a pilot study. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:978–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.013. discussion 982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrurier K, Liu J, Breckler F, et al. A multicenter evaluation of the role of mechanical bowel preparation in pediatric colostomy takedown. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:190–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breckler FD, Rescorla FJ, Billmire DF. Wound infection after colostomy closure for imperforate anus in children: utility of preoperative oral antibiotics. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1509–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breckler FD, Fuchs JR, Rescorla FJ. Survey of pediatric surgeons on current practices of bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery in children. Am J Surg. 2007;193:315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.026. discussion 318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravante G, Caruso R, Andreani SM, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis on abdominal and systemic complications on almost 5,000 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1145–1150. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0592-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contant CM, Hop WC, van’t Sant HP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61905-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris LJ, Moudgill N, Hager E, et al. Incidence of anastomotic leak in patients undergoing elective colon resection without mechanical bowel preparation: our updated experience and two-year review. Am Surg. 2009;75:828–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucher P, Gervaz P, Soravia C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective left-sided colorectal surgery. The British journal of surgery. 2005;92:409–414. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miettinen RP, Laitinen ST, Makela JT, et al. Bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution vs. no preparation in elective open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:669–675. doi: 10.1007/BF02235585. discussion 675–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rangel SJ, Narasimhan B, Geraghty N, et al. Development of an internet-based protocol to facilitate randomized clinical trials in pediatric surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:990–994. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.33826. discussion 990–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss RL, Henry MC, Dimmitt RA, et al. The role of prospective randomized clinical trials in pediatric surgery: state of the art? J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1182–1186. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.25749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]