Abstract

Background

Obstetrics and gynecology residents face difficult clinical situations and decisions that challenge their moral concepts.

Objective

We examined how moral and nonmoral judgments about patients are formulated, confirmed, or modified and how moral distress may be alleviated among obstetrics-gynecology residents.

Methods

Three focus groups, guided by open-ended interview questions, were conducted with 31 obstetrics-gynecology residents from 3 academic medical institutions in northeast Ohio. Each focus group contained 7 to 14 participants and was recorded. Two investigators independently coded and thematically analyzed the transcribed data.

Results

Our participants struggled with 3 types of patients perceived as difficult: (1) patients with chronic pain, including patients who abuse narcotics; (2) demanding and entitled patients; and (3) irresponsible patients. Difficult clinical encounters with such patients contribute to unalleviated moral distress for residents and negative, and often inaccurate, judgment made about patients. The residents reported that they were able to prevent stigmatizing judgments about patients by keeping an open mind or recognizing the particular needs of patients, but they still felt unresolved moral distress.

Conclusions

Moral distress that is not addressed in residency education may contribute to career dissatisfaction and ineffective patient care. We recommend education and research on pedagogical approaches in residency education in a model that emphasizes ethics and professional identity development as well as the recognition and alleviation of moral distress.

What was known

Moral distress after clinical encounters can contribute to unsafe or poor-quality patient care and reduced job satisfaction.

What is new

Focus groups with obstetrics-gynecology residents confirm presence of moral distress, originating from the difficult clinical encounters and moral dilemmas that are regularly experienced.

Limitations

Small sample size limits generalizability.

Bottom line

Educators should recognize moral distress in residents to promote improved resident well-being and professional development.

Introduction

Obstetrics and gynecology residents who have to cope with difficult patient encounters struggle to prevent the disintegration of the therapeutic relationship and the accompanying feelings of moral distress. Moral distress, often cited in nursing literature, has not been adequately explored in graduate medical education and physician practice. “[M]oral distress is [defined as] when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.”1 Moral distress after clinical encounters, along with moral dilemmas, has been implicated in emotional distress, unsafe or poor-quality patient care, reduced job satisfaction, and attrition in nursing.2–6

An extensive literature identifies the “difficult” patient and common characteristics and behaviors that compromise the therapeutic relationship, such as social class, occupation or employment status, appearance, age, cleanliness, and attire.7–11 Previous studies confirm the characterizations of difficult patients and, more broadly, difficult clinical encounters. However, there is a gap in the literature identifying moral distress among residents and its recognition and alleviation in residency education.

We examined how residents characterize difficult clinical encounters, the emotional responses to these encounters, and how judgments about patients are formulated, confirmed, or modified. By delving into what residents thought and felt about difficult clinical encounters, we identified that moral distress is correlated to unresolved situations or issues within those encounters. Finally, we recommend how residency education can provide obstetrics-gynecology residents with the tools to understand and resolve difficult encounters, ultimately alleviating their moral distress.

Methods

The authors developed open-ended focus group questions after conducting an extensive literature review about moral distress, difficult patient encounters, and gaps in obstetrics-gynecology resident education. One of the authors (J.A.) teaches in the residency programs at 2 of the 3 hospitals and regularly conducts clinical ethics consults (during which moral distress is often expressed by providers), serves as a member of an ethics committee, and is known to some of the residents who participated in this study. The authors facilitated 3 focus groups with 31 obstetrics-gynecology residents from 2 urban programs and 1 rural program. All are community-based, focusing on the care of underserved populations. Participants were invited via e-mail and in-person meetings. With the exception of postcall residents, nearly all of the residents from the 3 programs participated. Residents were diverse in level of training, sex, and race/ethnicity. Focus groups had 7 to 14 participants (a total of 23 women and 8 men) and were conducted in a private setting. Focus groups lasted up to 60 minutes. Beyond the sex of participants, no other demographic information was recorded to protect their confidentiality and the residency program in which they train. Participants were asked questions designed to encourage the expression of beliefs, feelings, and experiences surrounding difficult patient encounters, moral distress, and the process of making moral and nonmoral judgments.

Digital recordings of the focus groups were transcribed verbatim by the second author and qualitatively evaluated using thematic analysis to determine repetitive themes emerging from residents' quotes.12,13 Transcripts identified individuals by a number and their sex to keep track of individual and collective comments. Consistent with standard qualitative, thematic analysis, the authors independently coded transcripts to ensure reliability and met several times to compare major themes emerging from the data. Codes were interpreted and combined into overarching themes based on frequency and their relationships.14 There were no coding discrepancies. Qualrus software (Idea Works) was used to organize and combine codes for purposes of thematic analysis.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Northeast Ohio Medical University, Aultman Hospital, Akron City Hospital Summa Health System, and Akron General Medical Center.

Results

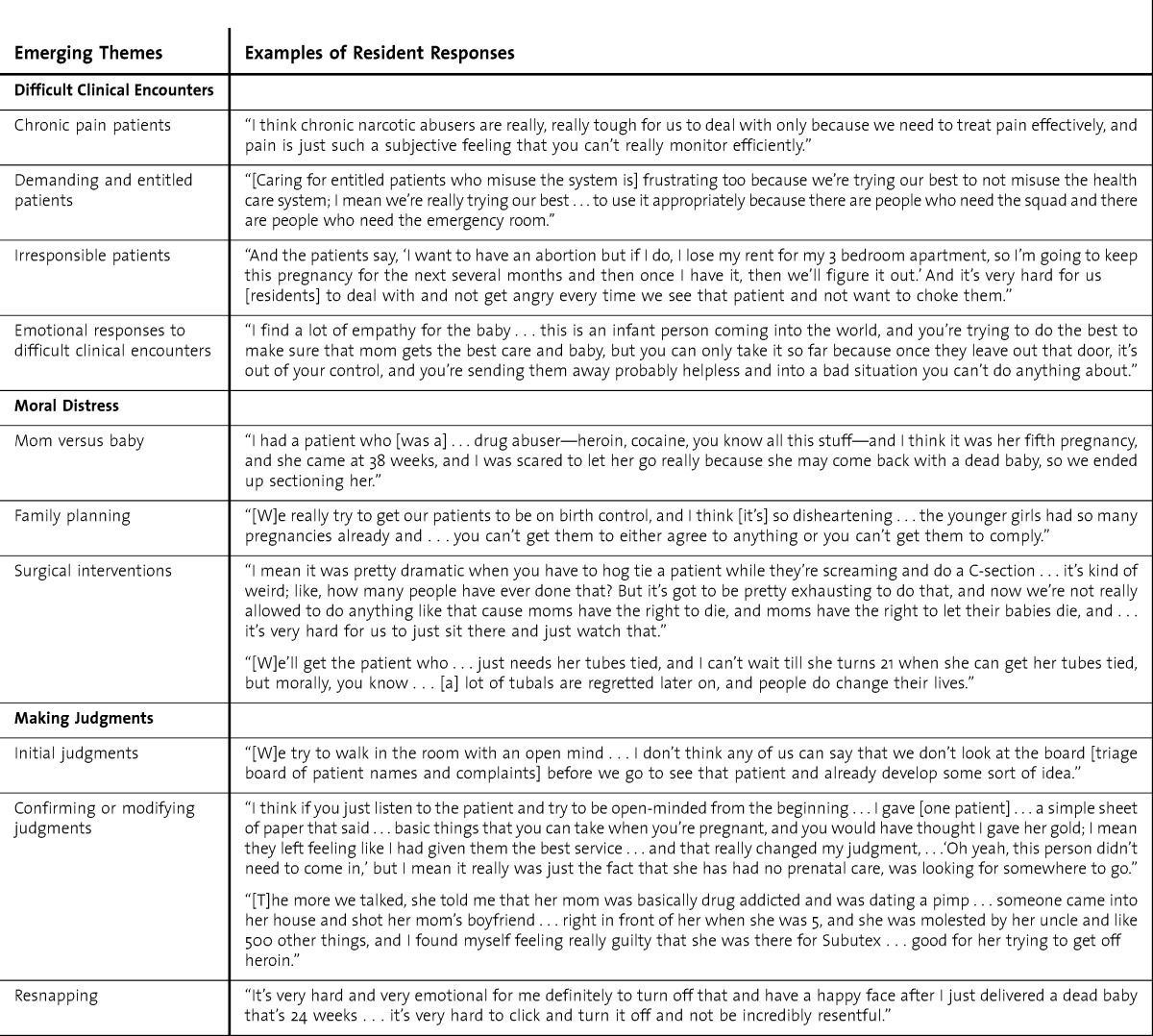

Residents were asked to describe occasions when they experienced difficult encounters. From this, 3 themes without discrete boundaries emerged: (1) patients with chronic pain, including users of narcotics; (2) entitled patients or those making seemingly unreasonable demands; and (3) irresponsible patients. In describing these encounters, residents discussed their emotional responses to difficult patients, the moral distress they feel and need to alleviate, and their ability to redirect or alter negative judgments to avoid a negative effect on patient care. The emerging themes with supporting quotes are found in the table.

TABLE.

Themes and Responses

Difficult Patient Encounters

All 3 focus groups identified chronic pain patients, including narcotic abusers, as difficult and reported that they struggle to make clinical and moral decisions in providing care because they do not know “what it is like to be in pain, or addicted to narcotics.” They also struggled with their ability to “still take care of the patient without harming them.” Residents from each group explained their caution in believing patients' level of pain and their intentions with prescribed medication. One resident refused to prescribe pain medications for a patient who she suspected was “not in need,” and subsequently was told she was a “bad doctor.”

Related to this theme are patients who are demanding or entitled, often also because they want pain medications. According to the residents, these patients become demanding by dictating what their health care providers should or should not provide. One resident commented: “I had a patient … [who] actually tried to use her kids to try and get what she wanted, which was clearly pain medication and excuses to not work, and her justification was her kids were going to lose their insurance.”

Residents reported that they felt frustrated when entitled patients have access to and abuse resources such as government aid. Residents described the misuse or misappropriation of resources, especially the use of emergency services for nonemergency patients, or requests for forms of treatment the residents viewed as being ill-advised from a medical or long-term health perspective as a source of distress. They reported feeling disappointed and frustrated over the incongruent values and goals within the therapeutic relationship, their perception of injustice in the health care system, and their perceived inability to resolve these problems.

A third theme emerged around irresponsible patients, defined as patients whose lifestyle choices or social and economic status contributes to their poor health (eg, patients who are obese, smoke, or are uninsured and patients whose therapies have been unsuccessful or have been terminated because of their resistance to medical advice. One resident commented: “[Some patients] are irresponsible…they're either seen by us because they are poor and they can't get insurance—and we'll see anybody and provide them with financial assistance—or no one else in the community will see them.”

Other types of irresponsible patients include young and naïve pregnant patients. Residents perceived this subgroup to lack a sense of duty to their baby and/or a lack of taking responsibility for contraception.

Emotional Responses and Moral Distress

In discussing difficult clinical encounters, residents expressed a range of emotions, including frustration, anger, and empathy. Most notably, they expressed moral distress and the unnerving emotional battle within themselves. One resident stated, “It's like this constant … tug-of-war, and … I feel like medicine wasn't set out to be like that.” Our participants expressed conflict over what is morally and clinically right, especially surrounding 4 particular themes: whom to care for (mom or baby), family planning, miscarriages, and surgical interventions.

The residents felt moral distress when expecting parents failed to change unhealthy behaviors or to adhere to recommendations and treatment; they felt torn regarding where their obligations are—the mother or the baby—and caring for both seems unattainable to them. One resident explained, “[M]orally you … want to help the baby. And, you know it's distressing to you because you can't.” Moral distress emerged when residents perceived they were carrying the burden for people who did not take responsibility for their own health or that of their child.

Family planning also contributes to the moral distress of residents. Specifically, residents reported feeling conflicted in preserving reproductive freedoms for some patients (eg, chronic drug abusers). Other encounters that lead to moral distress involved young adult patients requesting tubal ligation as birth control. Residents felt morally conflicted having to comply with such requests as they do not want to cause unnecessary future harm to their patients (ie, taking away patients' ability to have children in the future) based on the assumption that patients will change their minds.

Modifying Judgments and “Resnapping”

Some residents reported how judgments about patients (acquired from triage lists, nurses, and other health care providers) are confirmed or modified through additional interactions and how further interactions prompted by patients' clinical needs often change their own negative perceptions of their difficult patients. Other residents explained how their judgments are modified after shocking encounters. A resident recalls walking into the room of a patient who was a heroin user: “She literally looked like the girl that you would see in the farm in Iowa milking a cow, and I actually walked out of the room, and I was [thinking] ‘I'm in the wrong room,’ and then went back in.”

Such shocking encounters enabled many residents to recognize how judgments made about patients' appearances and behaviors can be inaccurate and affect the quality of their care.

Participants also commented on a conscious effort to “snap/resnap” or “click on/off” their emotional responses and judgments about patients. This was reported as something different from the effort to confirm or modify their judgments, and it involved more patient interaction and reflection. Residents indicated that this type of thought process prompted them to continue care for patients without eliciting further emotions or solidifying judgments during the actual encounter. Some residents explained how they talk themselves out of judging or feeling negative emotions by “resnapping … back into things” or “snapping out” of a particular mindset, thus preventing the formation, confirmation, or modification of judgments about patients and situations. This snap/resnap concept was revealed in this study by several residents as a way to prevent feelings from affecting their professional responsibilities.

Despite the ability of some residents to click their emotions on and off, participants indicated a need to alleviate moral distress and commented on the buildup of emotions that accompanies caring for difficult patients and related moral dilemmas that often go unresolved. Crying, using humor, talking to colleagues and mentors, and establishing healthy boundaries between themselves and patients were reported as techniques to alleviate feelings of moral distress. Residents indicated that their participation in our study was useful because of the shared learning prompted by the discussions.

Discussion

We gained insight into the attitudes and feelings of obstetrics-gynecology residents who care for difficult patients, the development and alteration of judgments, the presence of moral distress (often as a result of conflicting judgments), and the need to alleviate this distress. Participants recognized the importance, and occasional inaccuracy, of their judgments, especially when placing patients into categories, although categorization of patients often may be essential to making an accurate differential diagnosis. Some participants perceived that they were forced to be detectives to determine the legitimacy of patients' complaints rather than critically thinking about diagnoses and treatment, especially for patients seeking pain medications.

A related role is that of gatekeeper. Participants felt that they are the institution's gatekeepers by determining the needs of patients and allocating resources based on those needs. They reported a perception that there was a lack of an objective system, particularly in managing and distributing resources to chronic pain patients. Specifically, participants indicated that they were concerned that incorrect interpretations of patients' pain may result in avoidable harm, such as suffering. Furthermore, regulations on narcotics put pressure on residents to reduce their prescriptions and compelled them to analyze the validity of their patients' claims. Residents noted that, as a consequence, some patients in genuine pain may not receive medication. Residents indicated that if they do not address the reported pain, their role as caregiver may not be legitimized. This lack of legitimization can lead to moral distress.15 Lack of legitimization appears to contribute to residents' categorization of a patient as “difficult.” When residents have trouble accurately characterizing their patients, they have trouble deciphering what symptoms are legitimate. Treating patients becomes arduous and may prohibit residents from fulfilling the primary role of caregiver, forcing them to assume secondary roles of “detective” or “gatekeeper.”

Residents have developed ways to manage these difficult patient encounters. Participants described a process termed “resnapping,” a conscious effort to separate emotional responses from the clinical encounter and prevent initial moral and nonmoral judgments from developing into permanent judgments and categorizations of patients. Despite this cognitive process, moral distress is prevalent among obstetrics-gynecology residents.

To reduce moral distress and legitimize residents as medical professionals, enhancing education in the principles of ethics may be beneficial, along with education to guide residents to become more aware of their thought processes (ie, resnapping), to better equip them to work through difficult ethical problems and contribute to dialogue as members of the clinical team.

There is a need to provide opportunities for residents to discuss their moral distress as a step toward alleviating negative feelings that may affect patient care. Although education in ethics is provided in many programs, education specifically focusing on moral distress and the impact of difficult clinical encounters requires further study and development.

We recommend that education focusing on narrative ethics should be studied for its effectiveness in alleviating moral distress and its impact on patient care. An intervention using narrative ethics could teach residents how to work through difficult patient encounters using patient stories, providing them with tools to guide decision making and reflection. In contrast to education in traditional ethical principles, narrative ethics recognizes the uniqueness of each clinical encounter and prompts physicians to justify their decisions and actions based on the individual life story or the stories of patients “to open up dialogue, challenge received views and norms, and explore tensions between individual and shared meanings.”16

Narrative ethics education may include the use of written short stories and reflective discussions as well discussion of difficult encounters. A reflective session, facilitated by an experienced health care professional, medical humanities scholar, and/or ethicist, can serve as a forum for residents who have identified difficult clinical encounter(s) and may have unresolved feelings and moral distress. By providing this facilitated educational experience where beliefs, feelings, and attitudes are explored, based on the literary elements of the stories being read, told, and openly discussed by the residents, individuals learn about themselves in relation to their patients and others and begin to understand the origins of their frustrations, biases, and moral distress. Despite the similarities in storytelling and the emotional impact of stories, the reflective sessions are for residents only and are different from an open forum for all health care professionals, like the Schwartz Center rounds (www.theschwartzcenter.org).

In addition, formal education about moral distress (what it is, its effects on the self and others, how to alleviate it) should be part of the curriculum. This would allow residents to identify and alleviate their moral distress while improving team-based critical thinking and solidarity.

The limitations of this study include its small sample of 27 residents in 3 programs, limiting generalizability. Additional limitations include the potential lack of participants' familiarity with the terms in the interview questions (eg, moral distress, stigma).

Our findings suggest that ethics education for residents can be enhanced by integrating narrative ethics. Future research is needed to study the effectiveness of these pedagogical strategies in relation to moral distress.

Conclusion

Moral distress is present among obstetrics-gynecology residents, and it originates from difficult clinical encounters and moral dilemmas that are regularly experienced. Residents identified several coping mechanisms to manage their distress, including the technique of resnapping. The findings of this study are important to practitioners and educators, as they suggest the presence of moral distress that is not fully addressed in residency education. Educators should recognize moral distress in residents to promote improved resident well-being and professional development and to prevent damaging categorization of patients, inaccurate judgments, and a negative effect on the quality of care.

Footnotes

Julie Aultman, PhD, is Associate Professor, Family and Community Medicine, Northeast Ohio Medical University; and Rachel Wurzel, BS, is an MD Candidate, Northeast Ohio Medical University.

Funding: Part of the research was supported through a medical student summer research fellowship.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

The authors would like to thank Amy Burkett, MD, and Edward M. Ferris, MD, Summa Health System, Akron, Ohio, for their insightful guidance and assistance in recruitment of subjects.

References

- 1.Jameton A. Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin W, Kelecevic J, Goble E, Mekechuk J. An overview of moral distress and the paediatric intensive care team. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(1):57–68. doi: 10.1177/0969733008097990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavaliere TA, Daly B, Dowing D, Montgomery K. Moral distress in neonatal intensive care unit RNs. Adv Neonatal Care. 2010;10(3):145–156. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3181dd6c48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corley M, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M. Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(4):381–390. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne809oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varcoe C, Pauly B, Storch J, Newton L, Makaroff K. Nurse's perceptions of and responses to morally distressing situations. Nurs Ethics. 2012;19(4):488–500. doi: 10.1177/0969733011436025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson JM. Moral distress in nursing practice: experience and effect. Nurs Forum. 1988;23(1):17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baum N. Dealing with difficult patients. J Med Pract. 2009;25(1):33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill TE. How clinicians make (or avoid) moral judgments of patients: implications of the evidence for relationships and research. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2010:5–11. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-5-11. doi:10.1186/1747-5341-5-11. http://www.peh-med.com/content/5/1/11. Accessed April 8, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miksanek T. On caring for ‘difficult’ patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(5):1422–1428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinmetz D, Hava T. The difficult patient as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract. 2001;18(5):495–500. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.5.495. http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/content/18/5/495.full.pdf+html. Accessed June 5, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly MP, May D. Good and bad patients: a review of the literature and theoretical critique. J Adv Nurs. 1982;7:146–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1982.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy J. Principlism or narrative ethics: must we choose between them. J Med Ethics. 2003;29:65–71. doi: 10.1136/mh.29.2.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]