Abstract

Background

Education in health policy and advocacy is recognized as an important component of health professional training. To date, curricula have only been assessed at the medical school level.

Objective

We sought to address the gap in these curricula for residents and other health professionals in primary care.

Innovation

We created a health policy and advocacy curriculum for the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education, an interprofessional, ambulatory-based, training program that includes internal medicine residents, nurse practitioner fellows, health psychology fellows, and pharmacy residents. The policy module focuses on health care finance and delivery, and the advocacy module emphasizes negotiation skills and opinion-based writing. Trainee attitudes were surveyed before and after the course, and using the Wilcoxon signed rank test, relative change was determined. Knowledge acquisition was evaluated with precourse and postcourse examinations using a paired sample t test.

Results

From July 2011 through June 2013, 16 trainees completed the course. In the postcourse survey, trainees demonstrated improved comfort with understanding health law and the American health care system (Likert mean increased from 2.1 to 3.0, P = .01), as well as with associated advocacy skills (Likert mean increased from 2.0 to 2.9, P = .04). Knowledge-based test scores also showed significant improvement (increasing from 55% to 78% correct, P ≤ .001).

Conclusions

Our curriculum integrating core health policy knowledge with advocacy skills represents a novel approach in postgraduate health professional education and resulted in sustained improvement in knowledge and comfort with health policy and advocacy.

What was known

Health policy and advocacy curricula for residents and other health professions trainees appear to be lacking.

What is new

A Veterans Affairs–developed, dedicated curriculum for residents and other graduate health professionals working in primary care settings.

Limitations

Single-site study and nonvalidated assessment instruments may limit generalizability.

Bottom line

A Veterans Affairs health policy and advocacy curriculum for residents and other professionals may be useful for adoption or adaptation in other postgraduate training contexts.

Editor's Note: The online version (46.5KB, doc) of this article contains knowledge questions used in the study.

Introduction

With increased attention on US health care reform, health policy, leadership, and advocacy skills are becoming critical components of health professional training. The importance of integrating health policy into graduate medical education has been well recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.1 However, most existing programs have been designed for medical school education,2,3 and few offer formal training for medical residents and other health professionals.2–8 We created a novel, longitudinal course for internal medicine residents and other interprofessional trainees during ambulatory rotations at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System and evaluated changes in trainee attitudes and knowledge base.

Methods

Participants

We designed a health policy, leadership, and advocacy curriculum for the VA Connecticut Healthcare System Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). The VA Connecticut Healthcare System CoEPCE aims to transform interprofessional education for internal medicine residents, pharmacy residents, health psychology fellows, and post-Master's nurse practitioners, who are completing a 12-month adult primary care fellowship. Residents and the CoEPCE physician codirector developed the course, which required significant initial time commitment but minimal material costs.

All interprofessional trainees participated in the health policy and advocacy curriculum between July 2011 and June 2013.

Curriculum Design

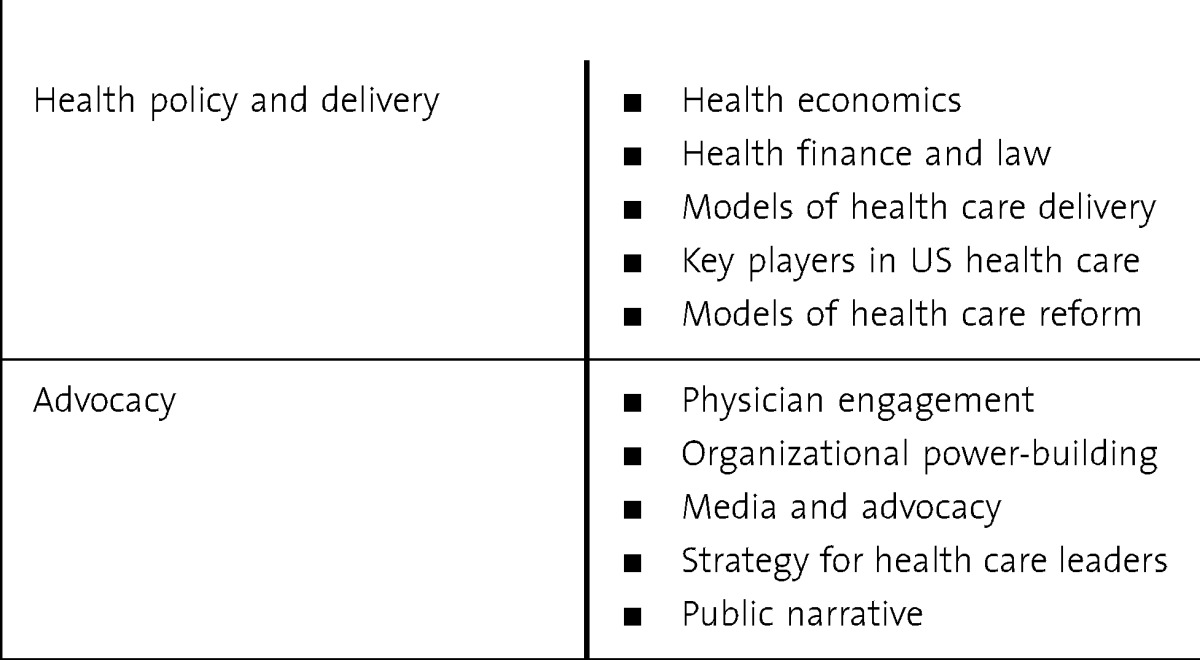

We divided the curriculum into 2 sections: health policy and delivery and advocacy (table 1). The faculty full-time equivalent was approximately 0.1, and the resident full-time equivalent was approximately 0.3. Both were divided between multiple faculty and trainees. Faculty funding was provided through the CoEPCE grant, as well as through the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Resident time was supported through standard postgraduate medical education funding mechanisms, and time allocated to the curriculum was a result of the grant.

TABLE 1.

Sections of Course

Section 1: Health Policy and Delivery

Six modules, each lasting 1 1/2 hours, comprised didactic, fact-based lectures, followed by case-based discussions to prompt critical thinking. Topics included (1) health care economics, (2) malpractice regulations and the creation of managed health care organizations, (3) stakeholders in the health care system nationally, (4) models of health care delivery, and (5) health care reform. This module culminated in a debate, requiring the use of acquired competencies to explore and develop health care policy arguments relevant to the Affordable Care Act.

Section 2: Advocacy

Six modules, lasting 1 to 3 hours each, focused on predetermined key advocacy skills—public speaking, opinion-based writing, and debate strategy—using workshops designed to apply knowledge and skills into practice. Trainees participated in creating opinion editorials and letter-to-editor pieces for publication through a writer's workshop in which participants were asked to compose 1-page opinion pieces.

The final assignment at the end of the academic year consisted of the collaborative development of a “white paper” synthesizing the knowledge and perspectives of participating health professional trainees into a statement of principles regarding the need to improve interprofessional education. This activity included anonymous, opinion-based writing followed by a roundtable discussion and negotiation to discuss areas of divergence and to create common ground.

Evaluation

We evaluated our curriculum with precourse and postcourse attitude surveys and precourse and postcourse knowledge-based examinations. As further evidence of impact, we kept track of the publications created from the curricular modules. The surveys were based on previous studies and were expanded to account for our unique curriculum components.4,5 The knowledge-based surveys consisted of 10 questions.

Approval from the VA Institutional Review Board was obtained for evaluation of educational outcomes of this project.

Analysis

We conducted a Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare precourse and postcourse attitude change along a Likert scale continuum. Precourse and postcourse change in overall knowledge scores was assessed using a paired sample t test. Trainees were asked the same 10 content-driven questions before their first session and at the end of the academic year. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P ≤ .05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp LP).

Results

Trainee Characteristics

During the course of 2 years, participants included internal medicine residents (n = 8), nurse practitioner fellows (n = 6), and clinical pharmacy residents (n = 2). Twelve trainees (75%) returned the survey and knowledge-based tests precourse, and 16 (100%) returned surveys and tests postcourse.

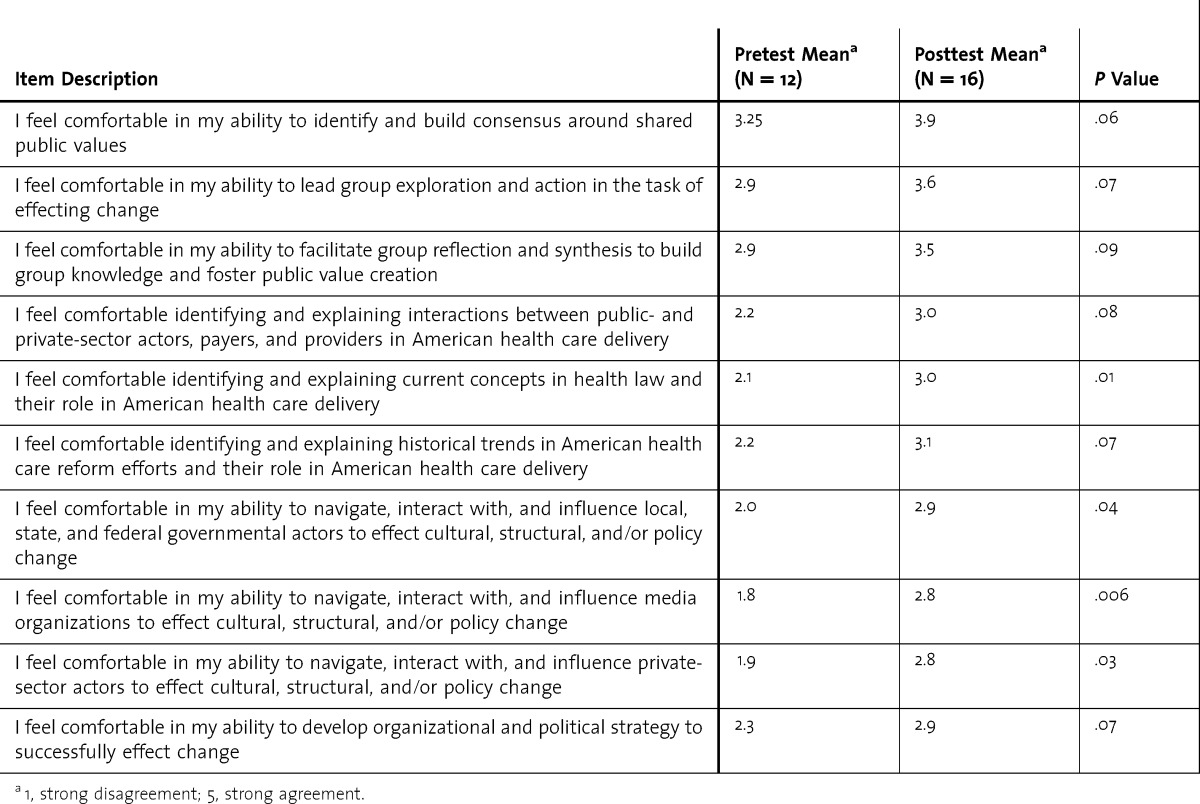

Attitude Questions

Attitudes toward learning health policy and perceived comfort with certain topics significantly improved in the postcurriculum survey (table 2). Trainees' comfort levels with laws affecting health care and the American health care system also improved (P = .01). Finally, trainee confidence increased regarding navigating local, state, and national health care systems to advocate for patients (P = .04) and leading an interprofessional team (P = .01).

TABLE 2.

Attitudes of Trainees Regarding Health Policy Education

Knowledge Questions

At the end of the academic year, trainees had improved individual examination scores for key content areas. The difference between before and after, knowledge-based questions improved significantly, from 55% to 78% correct (P ≤ .001).

Products Generated From Trainees

To date, trainees have published opinion editorials and letter-to-editor pieces in the Washington Post,9 Yale Daily News,10 Connecticut Post,11 and Academic Medicine.12

Discussion

Our curriculum integrating core health policy knowledge and advocacy skills represents a novel approach in postgraduate health professional education, and the evaluation during the first 2 years of the program indicates trainees feel significantly more comfortable in their understanding of health policy after participating in the course. In addition, trainees demonstrated comfort with advocacy by the collaborative development of the white paper and the publication of opinion-based articles.9–12

Currently, health policy curricula that have been studied are designed for medical students and have found improved learner comfort with health policy topics.2,3 Our graduate cohort of residents and other health profession trainees indicated increased comfort in navigating the health care system and strengthened advocacy skills. We also found that trainees demonstrated a significant retention of core health policy concepts and facts.

Our study has several limitations. First, the survey and knowledge-based test used have no validity evidence. They were based on previously reported tools and were adapted for our unique curriculum. Second, we did not have a control group, which would allow for a comparison with the intervention of the curriculum because we included all CoEPCE participants.

Conclusion

We successfully implemented a curriculum integrating core health policy knowledge with advocacy skills in a busy academic setting. Our approach could be considered a model for health policy and advocacy education in other programs in a primary care setting.

Footnotes

All authors are with VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education. Theodore Long, MD, is Faculty Attending, and Clinical Instructor and Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, Internal Medicine Residency Program, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine; Krisda H. Chaiyachati, MD, MPH, is Internal Medicine Resident, Internal Medicine Primary Care Residency Program, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine; Ali Khan, MD, MPP, is an Alum, Internal Medicine Residency Program, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine; Trishul Siddharthan, MD, is Internal Medicine Resident, Internal Medicine Primary Care Residency Program, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine; Emily Meyer, PhD, is Research Coordinator; and Rebecca Brienza, MD, MPH, is Co-Director, and Assistant Professor, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine.

Funding: This project was funded by the Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education of the Office of Academic Affiliations, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

An earlier version of the manuscript was presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, May 2012. A subsequent version of the manuscript was also presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, May 2013.

The authors would like to thank Dr Malcolm Cox for his visionary leadership for this program.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Medical specialties. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/368/ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines/MedicalAccreditation.aspx. Accessed September 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cha SS, Ross JS, Lurie P, Sacajiu G. Description of a research-based health activism curriculum for medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1325–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkel ML, Fein O. Teaching about the changing U.S. health care system: an innovative clerkship. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):179–182. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruen RL, Pearson SD, Brennan TA. Physician-citizens—public roles and professional obligations. JAMA. 2004;291(1):94–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ABIM Foundation; American Board of Internal Medicine; ACP-ASIM Foundation; American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logan JE, Pauling CD, Franzen DB. Health care policy development: a critical analysis model. J Nursing Educ. 2011;50(1):55–58. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20101130-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitcomb ME. Future doctors should learn about our country's health care system. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):105–106. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothman DJ. Medical professionalism—focusing on the real issues. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(17):1284–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanal Y. In the VA system, the future of primary health care. The Washington Post. November 30, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks E. It's still that bad. Yale Daily News. November 28, 2012;2 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price C. Keeping perspective in storm's wake. Connecticut Post. November 5, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan AM, Long T, Brienza R. “Surely, we can do better”: scaling innovation in medical education for social impact. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1645–1646. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182717e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]