Abstract

Oxygen affinity in heme-containing proteins is determined by a number of factors, such as the nature and conformation of the distal residues that stabilize the heme bound-oxygen via hydrogen-bonding interactions. The truncated hemoglobin III from Campylobacter jejuni (Ctb) contains three potential hydrogen-bond donors in the distal site: TyrB10, TrpG8, and HisE7. Previous studies suggested that Ctb exhibits an extremely slow oxygen dissociation rate due to an interlaced hydrogen-bonding network involving the three distal residues. Here we have studied the structural and kinetic properties of the G8WF mutant of Ctb and employed state-of-the-art computer simulation methods to investigate the properties of the O2 adduct of the G8WF mutant, with respect to those of the wild-type protein and the previously studied E7HL and/or B10YF mutants. Our data indicate that the unique oxygen binding properties of Ctb are determined by the interplay of hydrogen-bonding interactions between the heme-bound ligand and the surrounding TyrB10, TrpG8, and HisE7 residues.

Truncated hemoglobins (trHbs) belong to the hemoglobin superfamily of proteins. They are ~20–40 amino acids shorter than conventional globins. Instead of the 3-over-3 α-helical sandwich motif, trHbs adopt a 2-over-2 α-helical structure.1,2 Sequence analysis of more than 200 trHbs indicates that they can be divided into three groups: I, II, and III (sometimes referred as N, O, and P, respectively).2,3 Up to now, most studies on trHbs have been focused on trHb I and II groups of globins,1,4,5 whereas the group III is much less explored. Nonetheless, recently, the trHb III from the foodborne bacterial pathogen Campylobacter jejuni, Ctb, has been structurally and kinetically characterized.4,6–8

The globin function is typically characterized by its reactivity toward small ligands, such as O2, CO, and NO, which bind to the heme distal site.5,9–11 Among them, O2 is the most abundant and physiologically relevant ligand. In general, Hbs displaying a moderate oxygen affinity act as O2 carrier or storage,1,12 whereas those exhibiting a high oxygen affinity are involved in oxygen chemistry.4,5,13–16 To perform their designated functions, oxygen affinity of Hbs therefore has to be tightly regulated. The structural basis underlying O2 affinity of trHbs has been extensively studied.4–6,11,17–20 These studies show that O2 affinity is mainly modulated by hydrogen-bonding network between heme-bound O2 and amino acid residues located in the distal site of the heme.11,19 Depending on the distal interactions, oxygen dissociation rate (koff) can vary by more than 5 orders of magnitude.21 O2 affinity is also shown to be influenced by the ligand association rate (kon), which is intimately related to the presence of tunnels that facilitate ligand migration from the solvent toward the heme active site.22,23

Previous oxygen binding studies of trHb I from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mt-trHbN), an NO dioxygenase,23,24 showed an unusually high O2 affinity (Kd = 2.3 nM),4 allowing oxygen binding even at low O2 concentrations. The high oxygen affinity of Mt-trHbN is achieved by the presence of two polar residues in the distal site, TyrB10 and Gln E11,13,25 which form hydrogen bonds (HBs) with the heme-bound O2. Mutation of any of these residues to non-HB-forming residues significantly increases koff.26 The other trHb from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a trHb II (Mt-trHbO), also displays a high O2 affinity (Kd ~ 11 nM).4 Although Mt-trHbO contains three polar residues in the distal cavity, TyrB10, TyrCD1, and TrpG8, which can donate HBs to the bound O2, mutation of TyrB10 or TyrCD1 only slightly alter the koff, whereas the mutation of TrpG8 to Phe increases koff by 3 orders of magnitude.27 Computer simulation studies suggest that the increased koff of the G8 mutant arises from the larger flexibility of the TyrCD1 and LeuE11 side-chain groups.18 As TrpG8 is conserved throughout groups II and III of trHbs,28 these data highlight the pivotal role of TrpG8 in the structural and functional properties of these trHbs.

Like M. tuberculosis, C. jejuni contains two globins, Cgb and Ctb, which belong to the single-domain Hb (sdHb) and trHb III groups, respectively. Neither globin is essential for bacterial growth under laboratory conditions, yet both are up-regulated in response to nitrosative stress.29,30 Cgb has been suggested to function as a NO dioxygenase, similar to Mt-trHbN.20,31 On the other hand, the physiological function of Ctb is less clear.4,6 When the Ctb gene is knocked out in C. jejuni, the bacterium does not show extra sensitivity to nitrosative stress, but when grown under conditions of high aeration, the bacterium exhibits lowered respiration rates, suggesting a role of Ctb in modulating intracellular O2 flux.30,32

Ctb contains three polar residues in the distal cavity: TyrB10, HisE7, and TrpG8.8 Previous studies revealed that an intricate HB network involving the three distal polar residues, and the heme-bound ligand in Ctb leads to an extremely high oxygen affinity due to a slow dissociation rate (0.0041 s−1).6 Using CO as a probe, it was deduced that the electrostatic potential surrounding the ligand increases when TyrB10 and/or HisE7 are mutated to nonpolar substituents,6 in sharp contrast to the general trend observed in many other Hbs.4,6 Consistently, either single or double mutation in the TyrB10 and HisE7 residues significantly decreases O2 dissociation rate.6 Despite its importance, the mechanism by which the three distal polar residues control oxygen reactivity in Ctb remains unclear.

In order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the structural role of each distal polar residue in controlling oxygen affinity in Ctb, in this work we examined the structural and kinetic properties of the G8WF mutant of Ctb and compared them with those of the previously studied wild-type enzyme and its B10YF and E7HL mutants. The experimental data are complemented with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations,9,11,18,33,34 which have been shown to accurately reproduce the structure and dynamics of ligand-bound heme proteins.10,19,35 In addition, hybrid quantum mechanics–molecular mechanics (QM-MM) were employed to compute the oxygen binding energies of the wild-type and mutant proteins in order to rationalize the experimental data. Our data show that the unusual ligand binding characteristics of Ctb arise from a complex interplay between the structure and dynamics of the three distal polar residues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ctb Sample Preparation

The G8WF mutant was prepared using the Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. Primers were designed with the codon for the mutated amino acid in the center: forward primer (5′ CACTTAGATCTACCTCCTTTTCCTCAAGAGTTTTTTGAAATTTTTCTAAAACTTTTTGAAGAAAGTTTAAATATAGTTTTAATGAA 3′)- and reverse primer (5′ TTCATTATAAACTATATTTAAACTTTCTTCAAAAAGTTTTAGAAAAATTTCAAAAAACTCTTGAGGAAAAGGAGGTAGATCTAAGTG 3′). PCR was carried out on pBAD/His (Invitrogen) carrying the ctb gene using primers appropriate for the desired mutation. The PCR was then incubated with DpnI, an endonuclease specific for methylated DNA. The remaining nonparental mutated DNA was used to transform Escherichia coli XL1-Blue supercompetent cells. Constructs were checked by sequencing. The G8WF mutant of Ctb was expressed and purified in the same way as for wt Ctb.6,7 To form the CO-bound ferrous complexes, 12C16O (Tech Air, NY) or 13C18O (Icon Isotopes, Summit, NJ) was injected into sodium dithionite-reduced Ctb under anaerobic conditions. The 16O2-bound derivative was prepared by passing the CO-bound protein through a G-25 column to allow the exchange of CO with atmospheric 16O2 and to remove the excess of dithionite. The 18O2-bound sample was prepared by injecting 18O2 into an 16O2-bound protein solution, followed by spontaneous exchange of heme-bound 16O2 with 18O2. The concentration of the protein samples used for the Raman measurements was ~30 μM in 50 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.4 containing 50 μM EDTA.

Resonance Raman Measurements

The resonance Raman (RR) spectra were collected as previously described.6 Briefly, 413.1 nm excitation from a Kr ion laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) was focused to a ~30 μm spot on the spinning sample cell. The scattered light was collected by a camera lens, dispersed through a polychromator (Spex, Metuchen, NJ), and detected by a liquid nitrogen-cooled CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Princeton, NJ). A holographic notch filter (Kaiser, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to remove the laser scattering. Typically, the laser power was kept at ~1 mW and the spectral acquisition time was 60 min. The Raman shift was calibrated by using indene (Sigma) and an acetone/ferrocyanide (Sigma) mixture as the references for the 200–1700 and 1600–2200 cm−1 spectral window, respectively.

O2 Dissociation Kinetic Measurements

The O2 dissociation reaction was initiated by injecting a small volume (~50–60 μL) of concentrated O2-bound protein into a sealed quartz cuvette containing ~850–900 μL of pH 7.4 buffer (50 mM Tris and 50 μM EDTA) with 1 mM CO. The final concentrations of O2-bound protein and free oxygen were ~2–4 and 20 μM, respectively. The reactions were followed at 422 and 405 nm. The dissociation rate constants were calculated based on eq 1:20

| (1) |

O2 Association Kinetic Measurements

The O2 association reaction was measured with a nanosecond laser flash photolysis system (LKS.60 from Applied Photophysics).6 In this system, the 532 nm output (~5 ns, 110 mJ) from a Nd:YAG laser was employed as the photolysis beam. The output from a 150 W xenon arc lamp, at right angles to the photolysis beam, was used as the probe beam. The probe beam passed through a monochromator prior to reaching the quartz cuvette (4 × 10 mm with a 10 mm optical path) containing the sample. The light transmitted through the sample entered a second monochromator, which was synchronized with the first one, and was detected by a photomultiplier tube (1P28 from Hamamatsu Corp.). The signal from the photomultiplier tube was transferred to a digital oscilloscope (Infinium from Agilent Technologies) and then to a personal computer for subsequent analysis. Typically, five or six kinetic traces were averaged to obtain a satisfactory signal-to-noise ratio. The O2 association reaction was initiated by flashing off CO with the photolysis beam in a freshly prepared mixture of a dithionite-free CO-bound complex (with ~0.2 mM CO) in the presence of various concentrations of O2. Under the conditions applied, the rebinding of the CO to the heme iron was much slower than the O2 association reactions, which was monitored at 440 nm following the photolysis.

Classical Molecular Dynamics

MD simulations were performed starting from the crystal structure of wild-type (cyanomet form) Ctb (PDB entry 2IG3; monomer A at 2.15 Å resolution)8 with the CN− ligand replaced by O2. The system was immersed in an octahedral box of TIP3P36 water molecules. Simulations were performed under periodic boundary conditions and Ewald sums37 for treating long-range electrostatic interactions. The parm99 and TIP3P force fields, which are mean field, nonpolarizable potentials implemented in AMBER, were used to describe the protein and water, respectively. The heme parameters were obtained using the standard Amber protocol from QM calculations on model systems. These parameters have been successfully employed in previous papers of the group.9–11,19,22–24,37 The nonbonded cutoff used was 9 Å for the minimization and 12 Å for the equilibration and constant-temperature simulations. The temperature and pressure were regulated with the Berendsen thermostat and barostat, respectively, as implemented in AMBER. SHAKE was used to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms. The initial system was minimized using a multistep protocol and then heated from 0 to 300 K, and finally a short simulation at constant temperature of 300 K, under constant pressure of 1 bar, was performed to allow the systems to reach proper density. The final structure was used as the starting point for a 50 ns MD simulation at constant temperature (300 K). All mutations were performed in silico.

The feasibility of the conformational transition in the G8WF mutant was investigated by computing the free energy profile using umbrella-sampling techniques.38 To this end, the distance between the hydroxylic hydrogen of TyrB10 and the imidazole Nδ proton of HisE7 was used as distinguished coordinate. A set of windows of 0.1 Å, simulated for 0.4 ns each, was employed to scan the selected coordinate from 5.6 to 1.7 Å. Two independent sets of 12 windows each were employed to estimate the statistical error.

Hybrid Quantum Mechanics–Molecular Mechanics Calculations

The initial structures for the QM-MM calculations39 were taken from one representative snapshot of each conformation, which were cooled down slowly from 300 to 0 K and subsequently optimized. The iron porphyrinate plus the O2 ligand and the axial histidine were selected as the QM subsystem, while the rest of the protein and the water molecules were treated classically. All the QM-MM computations were performed at the DFT level with the SIESTA code40 using the PBE exchange and correlation functional.41 The frontier between the QM and MM subsystems was treated using the link atom method42,43 adapted to our SIESTA code. The ferrous pentacoordinated (5c) heme group was treated as a high-spin quintuplet state,44,45 while the ferrous–O2 complex was treated as a low-spin singlet state, as they are known to be the ground states of the system. Further technical details about the QM-MM implementation can be found elsewhere.46

Binding energies (ΔE) were calculated in selected conformations using eq 2:

| (2) |

where EHeme–O2 is the energy of the oxy form of the protein, EHeme is the energy of the deoxy form one, and EO2 is the energy of the isolated oxygen molecule. All the O2 binding energies for this work were calculated as stated above. Protein fluctuations influence protein–ligand interactions mainly by the dynamics of the H-bonding network, which may present more than one stable conformation. It is expected that most of protein fluctuation effects are due to these conformations and are of enthalpic nature.

There is a large amount of experimental evidence of the electric field influence on ligand binding in heme proteins. In this context, bound CO has been extensively used as a probe.47 In order to correlate the simulation results with experimental Raman spectra, we have performed an analysis of the QM-MM optimized structures using Badger’s rule,48 which has been successfully applied to ligand bound heme iron systems:49,50

| (3) |

where re is the equilibrium C–O distance and νe refers to ν(CO). The empirical parameters cij and dij were obtained from a fit of the computed optimized bond distances versus the experimental frequencies, 97.919 Å/cm2/3 and 0.557 Å, respectively. These empirical values were obtained plotting the RR frequencies vs the C–O bond distance from the QM-MM calculations. The structures for the vibrational calculation were obtained by QM-MM calculations over representative snapshots obtained from MD simulations of the CO complexes.

Furthermore, the electrostatic potential at oxygen atom from the CO ligand was computed for several snapshots taken from the trajectories of each representative conformation (25 snapshots per nanosecond of MD simulation). Electrostatic potential was computed using the following equation:

| (4) |

where ε0 is the permittivity in vacuum (8.8542 × 10−12 F/m), qi is the charge of each atom around the CO (heme atomic charges are not considered),47 r is the position of the oxygen from the CO ligand, and ri is the position of the atoms considered to compute the electrostatic potential.

Entropic Contribution Estimation

In this work, we employ a combination of both classical MD simulations to explore the protein conformational space and QM-MM calculations to obtain ligand binding energies with electronic detail. Because of the high computational expense of QM-MM calculations, we performed geometry optimizations in which thermal and entropic effects are not considered. However, on the other hand, in classical MD simulations thermal motions are allowed, and entropic effects are taken into account, since the sampling of different conformations is governed by the actual free energy surface. In order to obtain an estimation of entropic effects on hydrogen-bonding patterns, we have computed entropy, associated with the active site plus the distal aminoacids (TyrB10, HisE7, TrpE15, and TrpG8), by diagonalization of the Cartesian coordinate covariance matrix using the Schlitter method,51 used in previous works of the group.52 Because of sampling issues, entropy estimation is dependent on the time window employed, to compute accurate values requires very extended simulations. So, in the case of the entropy contribution to the different conformations, we are conditioned by the time each one remains stable. In spite the entropy is dependent on the sampling time (t), tending to a limit (S∞) at infinite simulation time.53 Calculated entropies could be fitted well using the empirical expression

| (5) |

RESULTS

Equilibrium Structural Properties of the O2-Adducts

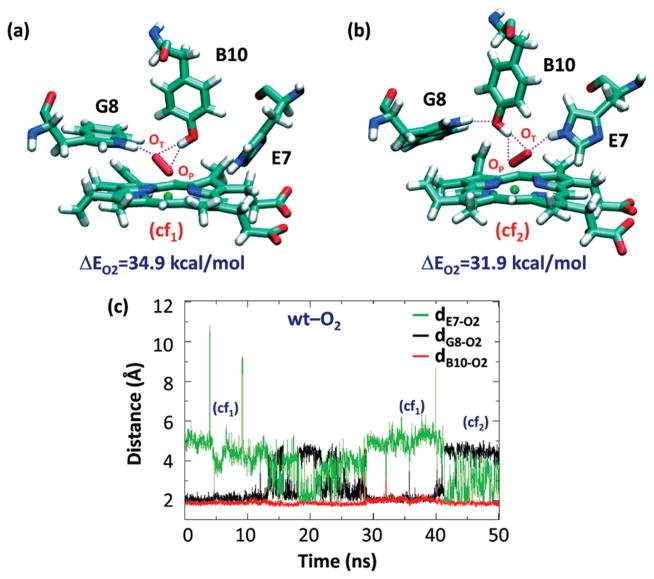

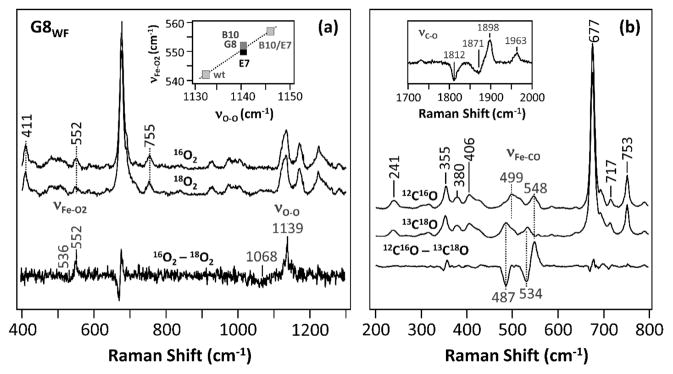

Previous RR work demonstrates that the νFe–O2 and νO–O modes of the oxy derivative of wt Ctb appear at 542 and 1133 cm−1, respectively.6 The νO–O mode of heme proteins with His as the proximal ligand is typically silent in RR spectra and was not experimentally observed until recently in several trHbs6,54,55 its appearance has been linked to a dynamic distal HB network.1 Likewise, a low νFe–O2 (<560 cm−1) has been shown to indicate strong HB interactions between the heme bound ligand and its environment.6 As shown in Figure 1a, the G8WF mutant exhibits νFe–O2 and νO–O modes at 552 and 1139 cm−1, respectively, pointing to a strong HB interaction between the ligand and the distal residues. As summarized in Table 1, the wild type and all the distal mutants of Ctb show νFe–O2 frequencies lower than 560 cm−1, consistent with a distal environment involving multiple H-bonding interactions.

Figure 1.

Resonance Raman spectra of the O2 (a) and CO (b) adducts of the G8WF mutant of Ctb. The data associated with the natural abundant and isotope-labeled ligands and the isotope-difference spectra are as indicated. The inset in (a) shows the correlation between νFe–O2 and νO–O.

Table 1.

νFe–O2, νO–O, νFe–CO, and νC–O Modes Determined by Resonance Raman Spectroscopy, O2 Dissociation and Association Rate Constants (koff and kon), and O2 Affinities (KO2), Calculated from kon/koff, of the Wild Type and Mutants of Ctb, Mt-trHbN, Mt-trHbO, and swMb

| species | protein | νFe–O2 (cm−1) | νO–O (cm−1) | νFe–CO (cm−1) | νC–O (cm−1) | kon (μM−1 s−1) | koff (s−1) | KO2 (μM−1) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctb (trHbIII) | wt | 542 | 1132 | 515 | 1936 | 0.91 | 0.0041 | 222 | 6 |

| E7HL | 550 | 1139 | 517, 557 | 1938, 1891 | 0.49 | 0.0003 | 1885 | 6 | |

| B10YF | 552 | 1139 | 524 | 1914 | 0.12 | 0.0027 | 44 | 6 | |

| B10YF/E7HL | 557 | 1144 | 521 | 1926 | 42 | 0.0028 | 15 000 | 6 | |

| G8WF | 552 | 1139 | 499, 548 | 1963, 1898 | 1.7 | 0.033 | 52 | this work | |

| Mt-trHbO (trHbII) | wt | 559 | 1140 | 525 | 1914 | 0.13 | 0.0014 0.0058 |

93 22 |

4, 26, 54 |

| Mt-trHbN (trHbI) | wt | 562 | 1139 | 500, 535 | 1916, 1960 | 71 | 0.16 | 444 | 4, 13, 63 |

| swMb | wt | 569 | 508 | 1947 | 17 | 15 | 1.1 | 1, 67 |

Equilibrium Structural Properties of the CO-Adducts

To further investigate the ligand–protein interactions in Ctb, CO was used as a structural probe for the distal pocket. Figure 1b shows the RR spectra of the 12C16O and 13C18O derivatives of the G8WF mutant of Ctb. As shown in the 12C16O–13C18O difference spectrum, two sets of νFe–CO/νC–O modes were found with values of 499/1963 and 548/1898, which shift to 487/1871 and 534/1812 cm−1, respectively, upon the substitution of 12C16O with 13C18O. It is widely accepted that, when CO is coordinated to the ferrous heme iron, the Fe–CO moiety may be represented by the resonance forms given in eq 6.56

| (6) |

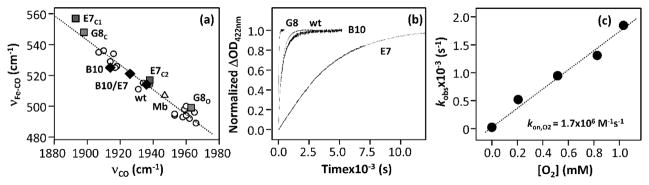

As a general rule, a positive polar environment destabilizes form (I) and facilitates iron π back-bonding interaction, leading to a stronger Fe–CO and weaker C–O bond. On this basis, the νFe–CO and νC–O typically follow a well-known inverse correlation as illustrated in Figure 2a.56–59 The location of the νFe–CO/νC–O data point on the inverse correlation line is suggestive of the electrostatic potential around the heme-bound ligand.60 Accordingly, we assigned the two sets of νFe–CO/νC–O modes of the G8WF mutant of Ctb at 499/1963 and 548/1898 cm−1 to an open and a closed conformation, respectively. In the closed conformation (G8C), the heme-bound CO is stabilized by strong HB interactions with its environment, whereas these interactions are absent in the open conformation (G8O).

Figure 2.

νFe–CO/νC–O inverse correlation plot (a) and the O2 dissociation kinetic traces (b) of the wild type and mutants of Ctb, as well as a plot of kobs vs O2, associated with the O2 association reaction of the G8WF mutant of Ctb (c). In (a, b) E7, B10, B10/E7, and G8 stand for the E7HL, B10YF, B10YF/E7HL, and G8WF mutants, respectively.

In the wt protein, only one set of νFe–CO/νC–O modes at 515/1936 cm−1 was observed (located at the middle of the correlation line in Figure 2a), indicating a distal environment with a medium positive electrostatic potential. The B10YF/E7HL and B10YF mutations cause the data to shift slightly up along the inverse correlation line, suggesting an increase in the distal electrostatic potential. The E7HL mutation, like the G8WF mutation, leads to the presence of two conformations: one (E7C1) looks like G8C, while the other (E7C2) resembles the wt protein. The RR data, together with the kinetic data described below, are summarized in Table 1.

Oxygen Dissociation Kinetics

The O2 dissociation reactions were measured by spontaneous exchange of O2 in the O2-bound protein with CO as described in the Materials and Methods section. Figure 2b shows the O2 dissociation kinetics of the wt and mutant Ctb proteins. All the kinetic traces follow single-exponential functions. As listed in Table 1, the dissociation rate of the G8WF mutant, 0.033 s−1, is significantly faster than those of the wt and other distal mutants, manifesting the importance of the TrpG8 residue in stabilizing heme-bound O2 in Ctb. However, the rate is still ~400-fold slower than that of swMb.

Oxygen Association Kinetics

The O2 association reaction was measured by flash photolysis of CO from the CO-bound complex in the presence of various concentrations of O2. The kinetic traces obtained for the G8WF mutant are shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. The bimolecular rate constant, kon, obtained from the concentration-dependent plot (Figure 2c) is 1.7 × 106 M−1 s−1, which is 2-fold faster than that of the wt protein6 but 8-fold slower than that of swMb (Table 1). The oxygen affinity (KO2) of the G8WF mutant, calculated based on the ratio of kon versus koff, is 52 μM−1, which is 4-fold lower than the wt protein but is ~40-fold higher than that of swMb. As listed in Table 1, the distal mutations in Ctb cause the oxygen affinity to vary over 3 orders of magnitude, highlighting the importance of the HB interactions involving TyrB10, HisE7, and TrpG8 in controlling ligand binding in Ctb.

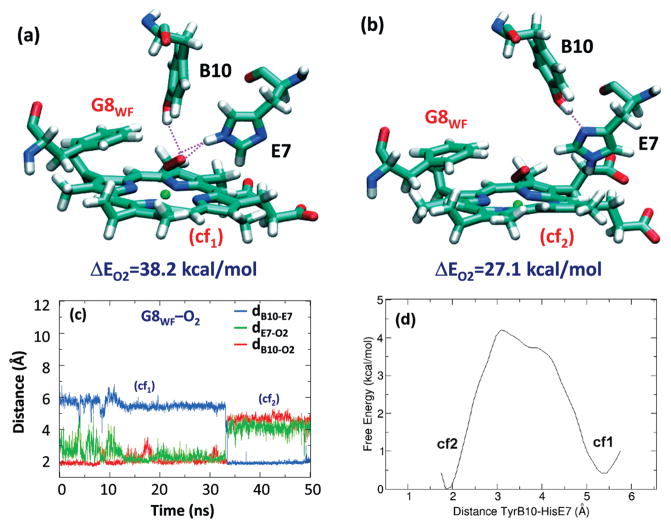

MD Simulations of the Wild-Type Protein

To investigate the molecular details governing the ligand–protein interactions in the O2-adducts of Ctb, 50 ns MD simulation was performed on the oxygenated wt protein. Visual inspection of the distal site reveals two distinct conformations, cf1 and cf2 (Figure 3a,b), which interconvert along the time scale of the MD simulation (see Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the distal site of wt Ctb in two representative conformations (a, b) and the time evolution of dB10–O2, dG8–O2, and dE7–O2 during the 50 ns MD simulations of the O2-adduct (c). The distances associated with potential H bonds, dB10–O2, dG8–O2, and dE7–O2, are defined as the distances between the terminal oxygen of the O2 ligand and the hydroxylic hydrogen of the TyrB10, the indole Nε proton of the TrpG8, and the imidazolic Nε proton of the HisE7. The O2-binding energy (ΔEO2) associated with each conformation in (a, b) resulting from QM-MM calculations is also indicated.

In both cf1 and cf2, TyrB10 interacts with the bound oxygen, by forming stable HBs with both the terminal (OT) and proximal oxygen (OP) atoms. In addition, in cf1, the Fe–O–O moiety points toward TrpG8. As a consequence, TrpG8 is strongly hydrogen bonded to the OT atom (2.13 ± 0.27 Å), while the HisE7 is 4.65 ± 0.78 Å away from the OT atom. In cf2, the Fe–O–O moiety points to the HisE7 due to its ~180° rotation along the Fe–OP bond, and a new HB is established between HisE7 and OT (2.21 ± 0.33 Å). In this state, TrpG8 forms a HB with TyrB10, keeping the TrpG8 far from the dioxygen ligand. In general, both cf1 and cf2 are stable and well-sampled during the time course of the simulation; the heme-bound dioxygen ligand always accepts two HBs from the TyrB10 and one additional HB from either TrpG8 or HisE7 (in cf1 and cf2, respectively).

The deoxy derivative of the wt protein was also examined. The TyrB10 forms an HB with the HisE7 for the majority of the simulation time window (see Figure S2a in Supporting Information). This HB breaks occasionally, and the breaking is associated with the movement of TyrB10 toward the TrpG8 and TyrE15, with an averaged dB10–G8 significantly longer than dB10–E15. In the absence of this HB, HisE7 has no interactions and is able to change the conformation of its side chain in a similar way of the well accepted “E7 gate” in Mb.61,62 This conformation was observed in the X-ray structure.8 Once the O2 binds to the iron, a new HB between TyrB10 and the bound ligand is established, disrupting the TyrB10–HisE7 interaction (see Figure S2 in Supporting Information) and promoting oxygen interaction with TrpG8. During the simulation, several water molecules occasionally enter into the distal pocket and interact with the distal polar residues. This event has been observed in some MD simulations in both the presence and absence of ligand in the distal site. In any case, in the simulations, water molecules used different pathways, and their study is outside the scope of this work.

MD Simulations of the Distal Ctb Mutants

Like wt protein, the MD simulation of the G8WF mutant shows the interconversion between two conformations that exhibit distinct HB interactions (Figure 4). In cf1, TyrB10 donates a HB to OT (2.08 ± 0.29 Å), while HisE7 forms HBs with both oxygen atoms. In cf2, the side chain of HisE7 rotates ~180° along the Cβ–Cγ bond to accept an HB from TyrB10, preventing both distal residues forming HBs with the heme-bound ligand. In general, the heme-bound dioxygen accepts either 2–3 or 0 HB (Figure 4, a and b, respectively) from the surrounding environment. Extending the MD simulation to 80 ns (see Figure S3 in Supporting Information), the conversion of TyrB10 back to the cf1 conformation was observed during almost 10 ns. Taken together this fact and the results obtained for the wt Ctb, where TyrB10 seems to be the most important residue stabilizing the bound ligand, this behavior suggests that both conformations contribute significantly to the network of HB interactions present in the distal cavity of the G8 mutant oxy derivative. Moreover, the MD simulations indicate that the intercorversion between those conformations occurs in a time scale lower than that required for ligand dissociation. To determine the feasibility of the transition between both conformations, an umbrella sampling calculation was performed. The calculated free energy barrier, around 4 kcal/mol, agrees with the observation of interconversion between those conformations along the time scale of the simulation at room temperature (Figure 4d). In addition, to consider entropic effects in the hydrogen-bonding pattern in the G8WF mutant Ctb, we estimated entropy using the Schliter method using a sampling time of 15 ns. The value obtained (TΔS 0.51 kcal/mol) indicates, as expected, the minor influence of the entropic effects in this particular conformational exchange.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the distal site of G8WF mutant of Ctb in two representative conformations (a, b) and the time evolution of dB10–E7, dB10–O2, and dE7–O2 during the 50 ns MD simulations of the O2-adduct (c). The distances associated with potential HBs, dB10–-E7, dE7–O2, and dB10–O2, are defined as the distances between the hydroxylic hydrogen of the TyrB10 and the imidazolic Nδ proton of the HisE7 and between the terminal oxygen of the O2 ligand and the hydroxylic hydrogen of the TyrB10 and the imidazolic Nε proton of the HisE7, respectively. The O2-binding energy (ΔEO2) associated with each conformation in (a, b) resulting from QM-MM calculations is also indicated. The free energy profile associated with the transition between cf1 and cf2 is depicted in panel d. The distance associated with the energetic profile is defined as the distances between the hydroxylic hydrogen of the TyrB10 and the imidazolic Nδ proton of HisE7.

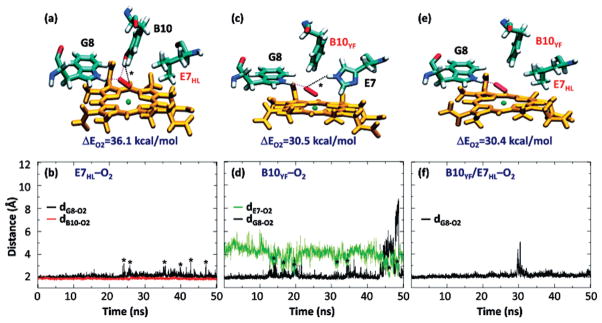

The MD simulation of the E7HL mutant shows only one stable conformation (Figure 5a), where the OT of the dioxygen ligand is stabilized by two HBs from TrpG8 (2.11 ± 0.29 Å) and TyrB10 (1.89 ± 0.17 Å), similar to the cf1 of the wt protein. As indicated by the asterisks in Figure 5a,b, an additional longer HB between the TyrB10 and the OP of the ligand can be formed transiently, with a mean distance of 2.44 ± 0.24 Å. During the time scale of the simulation, the LeuE7 side chain remains inside the heme pocket as its hydrophobic nature prevents its movement into the solvent. As compared to the wt protein, the data show that HisE7 is important in stabilizing cf2 by positioning the Fe–O–O moiety in an appropriate orientation for interaction with the TyrB10–TrpG8 pair.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the distal site of representative conformations of the E7HL, B10YF, and B10YF/E7HL mutants of Ctb (panels a, c, and e). Time evolution of dB10–O2, dG8–O2, and/or dE7–O2 during the 50 ns MD simulations of the O2-adduct of the E7HL, B10YF, and B10YF/E7HL mutants of Ctb (panels b, d, and f, respectively). The parameters dB10–O2, dG8–O2, and dE7–O2 are defined as the distances between the terminal oxygen of the O2 ligand and the hydroxyl proton of the TyrB10, the Nε proton of the TrpG8, and the Nε proton of the HisE7. These are depicted with red, black, and green lines, respectively. The O2-binding energy (ΔEO2) associated with each mutant in (a, c, and e) resulting from QM-MM calculations is listed as a reference. The transient H-bonds labeled in black dotted lines in (a) and (c), associated with the structures indicated by asterisks in (b) and (d), respectively, are described in the text.

In the B10YF mutant, TrpG8 forms an HB with OT (2.38±0.99 Å) during most of the simulation time (Figure 5c,d). Occasionally, this HB is broken due to rotation of the Fe–O–O moiety toward HisE7, with concomitant formation of a new HB between HisE7 and OT, as indicated by the asterisks. This conformational shift is similar to that observed in the wt protein, although in the absence of TyrB10 cf1 is strongly favored.

Additional mutation of HisE7 to Leu in the B10YF mutant (leading to the B10YF/E7HL double mutant) does not significantly alter the structural dynamics (Figure 5e,f), indicating that the transient HB interaction between HisE7 and the dioxygen ligand in the B10YF mutant is not critical for ligand escape. This scenario is consistent with the observation that the O2 dissociation rate constants for the B10YF and B10YF/E7HL mutants are very similar.

QM-MM Calculations of Oxygen Binding Energies

To estimate the protein–oxygen interaction in each representative Ctb structure obtained from the MD simulations, hybrid QM-MM calculations were performed to calculate the ligand binding energies of the O2-adducts. The results are listed in Table 2. No significant differences were observed for the geometric properties of the Fe–O–O moiety in all the energy-minimized structures of the various derivatives of Ctb. On the other hand, the charge on the heme-bound O2 (qO2) estimated using Mulliken populations varies significantly, ranging from −0.263 to −0.403. Nonetheless, the observed negative changes are consistent with the superoxide character of the bound dioxygen as revealed by the RR data (i.e., the νO–O modes at 1132–44 cm−1). The difference in qO2 indicates that the heme-bound ligand in each protein derivative is differentially polarized by the unique ligand environment with distinct electrostatic potential.

Table 2.

Structural and Energetic Parameters Obtained from MD simulations and QM-MM Calculations for the wt and Distal Mutants of Ctba

| protein | wt | G8WF | E7HL | B10YF | B10YF/E7HL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conformation | cf1 | cf2 | cf1 | cf2 | |||

| no. of H-bond | 3 | 3 | 2–3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| ΔEO2 (kcal/mol) | 34.9 | 31.9 | 38.2 | 27.1 | 36.1 | 30.5 | 30.4 |

| dFe–O (Å) | 1.85 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 1.77 | 1.77 | 1.77 | 1.78 |

| dO–O (Å) | 1.31 | 1.30 | 1.31 | 1.29 | 1.31 | 1.30 | 1.30 |

| φFe–O–O | 122.0 | 124.4 | 122.9 | 121.9 | 122.0 | 122.0 | 122.1 |

| qO2(e) | −0.403 | −0.337 | −0.388 | −0.263 | −0.367 | −0.297 | −0.302 |

| koff (s−1) | 0.0041 | 0.0330 | 0.0003 | 0.0088 | 0.0028 | ||

The O2 dissociation rate constants taken from Table 1 are listed as references.

The calculated O2 binding energies (ΔEO2) range from 27.1 to 38.2 kcal/mol. As expected, ΔEO2 values correlate with the number of HBs to the heme-bound ligand: the larger the number of HBs, the higher the binding energy. In addition, ΔEO2 also reveals subtle differences that arise from the nature and orientation of the involved HBs. For example, comparison of the cf1 and cf2 of the wt proteins (both displaying 3HBs) indicates that the HB donated by TrpG8 is stronger than that donated by HisE7, as suggested by the relatively higher binding energy of cf1 (34.9 vs 31.9 kcal/mol).

Previous computational studies of heme proteins showed that ΔEO2 is strongly correlated with O2 dissociation rate.9,11 Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that differences in O2 dissociation in the wt protein and its mutants will be mainly determined by the thermal breakage of protein–oxygen interactions in the heme active site. As listed in Table 2, the ΔEO2 values of all derivatives of Ctb are higher than that reported for Mb (27.0 kcal/mol), except the cf2 of G8WF. The observation is consistent with the lower koff observed in all derivatives of Ctb as compared to Mb. Moreover, the E7HL mutant, which displays the lowest koff value, shows the highest binding energy, when the data of G8WF are excluded. The higher dissociation rate of the G8WF mutant suggests that the protein is in a fast equilibrium between the high (cf1) and low (cf2) binding energy conformations and that the ligand dissociation mainly involves the low binding energy conformation (vide infra). The reported 10-fold increase in koff for the G8WF mutant corresponds to a ΔΔG of about 1 kcal/mol. Our results (binding energies of 34.9 and 31.9 kcal/mol for the wt and 38.2 and 27.1 kcal/mol for the G8WF mutant) are qualitatively consistent with the experimental value, since there is one conformation of the mutant with lower binding energy. However, due to limitations in sampling and force fields, it is not possible to obtain reliable populations necessary to obtain quantitative predictions.

To correlate the computed values with experiment, C–O frequencies of the conformations obtained from the MD simulations were estimated as well as the electrostatic potential on the oxygen atom of the bound CO ligand (see Table 3). The computed results, both calculated frequencies using eq 3 and electrostatic potential using eq 4, showed a good correlation with experimental data.

Table 3.

νFe–CO and νC–O Modes Determined by Resonance Raman Spectroscopy, dC–O Obtrained from the QM-MM Calculation of the Representative Conformations Observed in the MD, νC–O Calculated Using eq 3, and Electrostatic Potential at the Oxygen Atom of the CO in the Wild Type and Mutant Ctb Proteins (Relative to the Wild Type Value)

| Ctb protein | RR νFe–CO(cm−1) | RR νC–O(cm−1) | dC–O(Å) | calc νC–O(cm−1) | ΔVO (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt | 515 | 1936 | 1.187 | 1935 | 0.00 |

| E7HL | 517, 557 | 1938, 1891 | –, 1.196 | –, 1895 | –, 4.11 |

| B10YF | 524 | 1914 | 1.189 | 1926 | 3.04 |

| B10YF/E7HL | 521 | 1926 | 1.186 | 1940 | 2.32 |

| G8WF | 499, 548 | 1963, 1898 | 1.183, 1.200 | 1954, 1877 | 1.59, 4.47 |

DISCUSSION

Oxygen affinity is the key point in determining the heme protein function. To understand how structure and dynamics regulate O2 affinity, experimental or theoretical studies are commonly used. In this work we show how combining experimental and computer simulation approaches allows us to gain insight into the molecular basis of protein reactivity and structure.

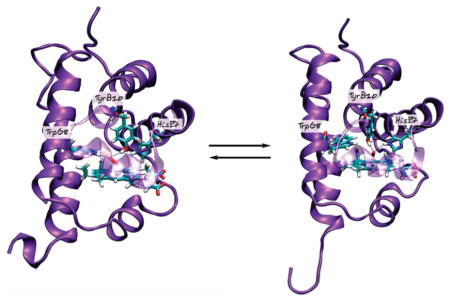

Structural Basis for the High Oxygen Affinity of Ctb

Since its discovery, the structural characterization of Ctb has been focused on the relative contribution of distal residues to ligand stabilization. Initial mutagenesis studies revealed that neither mutation of HisE7 nor TyrB10 to non-HB-forming residues increases the koff.6 The elevated koff for the G8WF mutant (10-fold higher than that for wt) presented herein suggests that TrpG8 provides the major contribution to ligand stabilization. Our RR data show that, in general, the heme-bound O2 in the wt and mutants of Ctb is stabilized by unique HB interactions with its surroundings, as all the νFe–O2 frequencies are <560 cm−1 and the νO–O are Raman-active.

The MD simulations demonstrate that, in the wt protein, the main residue responsible for oxygen stabilization is TyrB10. Bound oxygen is further stabilized by an additional HB from either TrpG8 (cf1) or HisE7 (cf2), which depends on the orientation of the Fe–O–O moiety (Figure 3a, b). The QM-MM data show that the HB with TrpG8 is stronger than that with HisE7, and therefore mutation of HisE7 leads to a higher binding energy and a lower koff by constraining Ctb to a cf1-like conformation.

In the O2-adduct of the G8WF mutant, two conformations were observed. In cf1 (Figure 4a), the heme-bound O2 is stabilized by both TyrB10 and HisE7. In cf2 (Figure 4b), a strong HB between TyrB10 and HisE7 is established, preventing either residue from interacting with the ligand, leading to low binding energy. The nature of the two conformers observed in the RR data of the G8WF Ctb CO-adduct (Figure 2a) is consistent with the existence of those conformations: the closed one (cf1), which leads to a strong positive polar electrostatic potential around the heme-bound ligand, and the open conformation (cf2), where the electrostatic potential is less positve. The relatively fast O2 dissociation rate of the G8WF mutant (Table 1) indicates that the dissociation reaction is likely influenced by the presence of the exchange between open and closed conformations, which interconverts in a time scale lower than the dissociation of O2 from the heme.

It is important to note that under equilibrium conditions the O2-adduct of the G8WF mutant exhibits only one νFe–O2 mode with a relatively low frequency (552 cm−1, see Table 1), indicating the presence of strong HB(s).6,55 Hence, the data suggest that the equilibrium favors the G8C conformer. In contrast, the coexistence of both conformations in the CO-adduct of the G8WF mutant indicates that both G8C and G8O are populated. The population shift toward G8O in the CO-adduct presumably reflects the smaller net partial charge of the heme ligand.

Also noteworthy is the fact that in the wt protein the CO-adduct exhibits only one conformation with medium polar electrostatic potential (Figure 2a), while the O2-adduct displays two conformations on the basis of MD simulations (Figure 3a, b). QM-MM studies of the O2-adduct show that the energy difference between these two conformations is small, as compared to the G8WF mutant (~3 vs 11 kcal/mol). Moreover, in the wt protein both conformations have the same number of HBs with the ligand, suggesting that the difference in the electrostatic potential surrounding the bound CO in the two conformations of the wt protein is too small to be resolved by the RR studies.

Even though more accurate entropic data were computed, the results obtained for the G8WF mutant confirm that the sampling of different conformations is governed by the actual free energy surface.

In the E7HL mutant, the Fe–O–O moiety is preferentially oriented toward TrpG8. The dioxygen ligand is stabilized by HBs donated by TrpG8 and TyrB10, leading to the highest oxygen binding energy and slowest dissociation rate. The HB with TrpG8, however, can be transiently broken due to the rotation of the Fe–O–O moiety. RR studies of the CO-adduct of the E7HL mutant revealed two conformations: E7C1 with a G8C-like high positive polar electrostatic potential and E7C2 with a wt-like medium positive polar electrostatic potential (Figure 2a). The E7C1 likely corresponds to the major conformation observed in the O2-adduct, whereas the E7C2 probably corresponds to the transient conformation, in which the HB donated from TrpG8 to the heme ligand is broken.

In the B10YF mutant, the O2 dissociation rate is 2-fold higher than that of the wt protein. MD simulations show that, when TyrB10 is mutated to Phe, the dioxygen ligand loses the constraint imposed by TyrB10; the Fe–O–O moiety rotates toward TrpG8, establishing a single yet strong HB with it. As a result, the oxygen binding energy decreases slightly, leading to a small increase in the koff. This is in contrast to Mt-trHbN, where the replacement of TyrB10 with Phe or Leu in Mt-trHbN results in a significant increase in the koff 4 due to the lack of TrpG8.

Hydrogen Bonding and the Regulation of Oxygen Affinity

The coexistence of multiple conformations for the residues in the distal cavity, each characterized by a distinct pattern of HB interaction, creates differences in the local polarity and affects the stabilization of the heme-bound ligand in Ctb. The existence of different HB networks is not a unique propety of Ctb. In fact, the plasticity of HB interactions between the heme ligand, TyrB10, Gln E7, Gln E11, TyrCD1, and/or TrpG8 residues has also been discussed in the single domain Hb from C. jejuni and two trHbs from M. tuberculosis.18 In addition, the interplay between distinct HB interactions between the heme ligand, TyrB10, Gln E7, and ThrE11 in the CerHb from Cerebratulus lacteus nerve tissue and the trHb I from Paramecium caudatum10,63–65 and those between the heme ligand, TyrB10, and HisE7 in soybean leghemoglobin65,66 have all been demonstrated to be important for regulating the oxygen affinities of these Hbs.

Physiological Implications

The requirement for a high oxygen affinity of Ctb in C. jejuni physiology is at present not understood. However, the microaerophilic lifestyle of this pathogen and a requirement to control intracellular oxygen concentrations and prevent oxidative stress may have resulted in the evolution of a globin with extraordinarily high affinity for oxygen.

CONCLUSION

Our results show that oxygen affinity of Ctb is intricately regulated by the existence of different hydrogen-bonding interactions between the heme-bound ligand and the three key distal residues: TyrB10, TrpG8, and HisE7. The results also show that the behavior of each residue is affected by the other residues, and therefore the binding affinity is the result of a cooperative property. The accurate description of the behavior of distal residues in all the studied mutants has potential implications for understanding and predicting O2 affinity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The authors thank the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (SAF2008-05595 and PCI2006-A7-0688), Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT06-25667), CONICET, Universidad de Buenos Aires, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and the European Union FP7 Program project NOstress for providing financial support for carrying out this work. The work was supported by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) through grant BB/EO10504/1. This material is partially based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No 0956358 (to S.R.Y.).

The authors are grateful to Dr. Pablo De Biase for his help in the computation of the electrostatic potential. The Barcelona Supercomputing Center, the Centre de Supercomputació de Catalunya, the Centro de Cómputos de Alto Rendimiento (CeCAR) at the Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales (FCEN) of the Universidad de Buenos Aires, and the Cristina supercomputer built with funding provided by ANPCYT through grant PME-2006-01581 are acknowledged for computational facilites.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Cgb

single domain hemoglobin from Campylobacter jejuni

- Ctb

truncated hemoglobin III from C. jejuni

- Hb

hemoglobin

- HB

hydrogen bond

- Mb

myoglobin

- MD

molecular dynamics

- QM-MM

quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics

- RR

resonance Raman

- sdHb

single domain hemoglobin

- swMb

sperm whale myoglobin

- trHb

truncated hemoglobin

- Mt-trHbN

truncated hemoglobin I from Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Mt-trHbO

truncated hemoglobin II from M. tuberculosis

Footnotes

Supporting Information. O2 association kinetic traces for the G8WF mutant of Ctb; time evolution of the intramolecular distances during 50 ns of MD simulation for the deoxy and O2-bound derivative of wt Ctb; time evolution of the intramolecular distances during 80 ns of MD simulation for the oxy derivative of the G8WF mutant of Ctb. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Egawa T, Yeh SR. Structural and functional properties of hemoglobins from unicellular organisms as revealed by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:72–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittenberg JB, Bolognesi M, Wittenberg BA, Guertin M. Truncated hemoglobins: A new family of hemoglobins widely distributed in bacteria, unicellular eukaryotes, and plants. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:871–874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vuletich DA, Lecomte JTJ. A phylogenetic and structural analysis of truncated hemoglobins. J Mol Evol. 2006;62:196–210. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu C, Egawa T, Mukai M, Poole RK, Yeh SR. Hemoglobins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Campylobacter jejuni: A comparative study with resonance Raman spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2008;437:255–286. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)37014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milani M, Pesce A, Nardini M, Ouellet H, Ouellet Y, Dewilde S, Bocedi A, Ascenzi P, Guertin M, Moens L, Friedman JM, Wittenberg JB, Bolognesi M. Structural bases for heme binding and diatomic ligand recognition in truncated hemoglobins. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu C, Egawa T, Wainwright LM, Poole RK, Yeh SR. Structural and functional properties of a truncated hemoglobin from a food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13627–13636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wainwright LM, Wang Y, Park SF, Yeh SR, Poole RK. Purification and spectroscopic characterization of Ctb, a group III truncated hemoglobin implicated in oxygen metabolism in the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6003–6011. doi: 10.1021/bi052247k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nardini M, Pesce A, Labarre M, Richard C, Bolli A, Ascenzi P, Guertin M, Bolognesi M. Structural determinants in the group III truncated hemoglobin from Campylobacter jejuni. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37803–37812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bikiel DE, Boechi L, Capece L, Crespo A, De Biase PM, Di Lella S, González Lebrero MC, Martí MA, Nadra AD, Perissinotti LL, Scherlis DA, Estrin DA. Modeling heme proteins using atomistic simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:5611–5628. doi: 10.1039/b611741b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marti MA, Bikiel DE, Crespo A, Nardini M, Bolognesi M, Estrin DA. Two distinct heme distal site states define Cerebratulus lacteus mini-hemoglobin oxygen affinity. Proteins: Struc Funct Bioinf. 2006;62:641–648. doi: 10.1002/prot.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marti MA, Crespo A, Capece L, Boechi L, Bikiel DE, Scherlis DA, Estrin DA. Dioxygen affinity in heme proteins investigated by computer simulation. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson JS, Phillips GN., Jr Kinetic pathways and barriers for ligand binding to myoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17593–17596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Couture M, Yeh SR, Wittenberg BA, Wittenberg JB, Ouellet Y, Rousseau DL, Guertin MA. Cooperative oxygen-binding hemoglobin from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11223–11228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouellet Y, Milani M, Couture M, Bolognesi M, Guertin M. Ligand interactions in the distal heme pocket of Mycobacterium tuberculosis truncated hemoglobin N: Roles of TyrB10 and GlnE11 residues. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8770–8781. doi: 10.1021/bi060112o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frey AD, Kallio PT. Bacterial hemoglobins and flavohemoglobins: versatile proteins and their impact on microbiology and biotechnology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:525–545. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner PR, Gardner AM, Brashear WT, Suzuki T, Hvitved AN, Setchell KD, Olson JS. Hemoglobins dioxygenate nitric oxide with high fidelity. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milani M, Savard PY, Ouellet H, Ascenzi P, Guertin M, Bolognesi M. A TyrCD1/TrpG8 hydrogen bond network and a TyrB10-TyrCD1 covalent link shape the distal heme distal site of Mycobacterium tuberculosis hemoglobin O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5766–5771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037676100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guallar V, Lu C, Borrelli K, Egawa T, Yeh SR. Ligand migration in the truncated hemoglobin-II from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: The role of G8 tryptophan. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3106–3116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806183200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capece L, Marti MA, Crespo A, Doctorovich F, Estrin DA. Heme protein oxygen affinity regulation exerted by proximal effects. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12455–12461. doi: 10.1021/ja0620033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu C, Mukai M, Lin Y, Wu G, Poole RK, Yeh SR. Structural and functional properties of a single domain hemoglobin from the food-borne pathogen Campylobactor jejuni. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25917–25928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson JS. Structural determinants of geminate recombination in myoglobin based on site-directed mutagenesis studies. J Inorg Biochem. 1993;51:216. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bidon-Chanal A, Marti MA, Estrin DA, Luque FJ. Dynamical regulation of ligand migration by a gate-opening molecular switch in truncated hemoglobin-N from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6782–6788. doi: 10.1021/ja0689987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marti MA, Bidon-Chanal A, Crespo A, Yeh SR, Guallar V, Luque FJ, Estrin DA. Mechanism of product release in NO detoxification from Mycobacterium tuberculosis truncated hemoglobin N. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1688–1693. doi: 10.1021/ja076853+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bidon-Chanal A, Martí MA, Crespo A, Milani M, Orozco M, Bolognesi M, Luque FJ, Estrin DA. Ligand-induced dynamical regulation of NO conversion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis truncated hemoglobin-N. Proteins: Struct Funct, Bioinf. 2006;64:457–464. doi: 10.1002/prot.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouellet YH, Daigle R, Lague P, Dantsker D, Milani M, Bolognesi M, Friedman JM, Guertin M. Ligand binding to truncated hemoglobin N from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is strongly modulated by the interplay between the distal heme pocket residues and internal water. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27270–27278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804215200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouellet H, Juszczak L, Dantsker D, Samuni U, Ouellet YH, Savard PY, Wittenberg JB, Wittenberg BA, Friedman JM, Guertin M. Reactions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis truncated hemoglobin O with ligands reveal a novel ligand-inclusive hydrogen bond network. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5764–5774. doi: 10.1021/bi0270337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouellet H, Milani M, LaBarre M, Bolognesi M, Couture M, Guertin M. The roles of Tyr(CD1) and Trp(G8) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis truncated hemoglobin O in ligand binding and on the heme distal site architecture. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11440–11450. doi: 10.1021/bi7010288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milani M, Pesce A, Ouellet Y, Ascenzi P, Guertin M, Bolognesi M. Mycobacterium tuberculosis hemoglobin N displays a protein tunnel suited for O2 diffusion to the heme. EMBO J. 2001;20:3902–3909. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monk CE, Pearson BM, Mulholland F, Smith HK, Poole RK. Oxygen- and NssR-dependent globin expression and enhanced iron acquisition in the response of Campylobacter to nitrosative stress. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28413–28425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wainwright LM, Elvers KT, Park SF, Poole RK. A truncated haemoglobin implicated in oxygen metabolism by the microaerophilic food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiology. 2005;151:4079–4091. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elvers KT, Wu G, Gilberthorpe NJ, Poole RK, Park SF. Role of an inducible single-domain hemoglobin in mediating resistance to nitric oxide and nitrosative stress in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5332–5341. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5332-5341.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elvers KT, Turner SM, Wainwright LM, Marsden G, Hinds J, Cole JA, Poole RK, Penn CW, Park SF. NsrR, a member of the Crp-Fnr superfamily from Campylobacter jejuni, regulates a nitrosative stress-responsive regulon that includes both a single domain and truncated haemoglobin. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:735–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bossa C, Anselmi M, Roccatano D, Amadei A, Vallone B, Brunori M, Di Nola A. Extended molecular dynamics simulation of the carbon monoxide migration in sperm whale myoglobin. Biophys J. 2004;86:3855–3862. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.037432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golden SD, Olsen KW. Identification of ligand-binding pathways in truncated hemoglobins using locally enhanced sampling molecular dynamics. Methods Enzymol. 2008;437:19. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)37023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capece L, Estrin DA, Marti MA. Dynamical characterization of the heme NO oxygen binding (HNOX) domain. Insight into soluble guanylate cyclase allosteric transition. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9416–9427. doi: 10.1021/bi800682k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luty BA, Tironi IG, van Gunsteren WF. Lattice-sum methods for calculating electrostatic interactions in molecular simulations. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:3014–3021. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leach AR. Molecular Modelling. 2. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warshel A, Levitt M. Theoretical studies of enzymic reactions: Dielectric, electrostatic and steric stabilization of carbonium ion in the reaction of lysozyme. J Mol Biol. 1976;103:227–249. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soler JM, Artacho E, Gale JD, García A, Junquera J, Ordejón P, Sánchez-Portal D. The SIESTA method for ab-initio Order-N materials simulations. J Phys: Condens Matter. 2002;14:2745. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/20/6/064208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eichinger M, Tavan P, Hutter J, Parrinello M. A hybrid method for solutes in complex solvents: Density functional theory combined with empirical force fields. J Chem Phys. 1999;110:10452–10467. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rovira C, Schulze B, Eichinger M, Evanseck JD, Parrinello M. Influence of the heme pocket conformation on the structure and vibrations of the Fe-CO bond in myoglobin: A QM/MM density functional study. Biophys J. 2001;81:435–445. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scherlis DA, Martí MA, Ordejón P, Estrin DA. Environment effects on chemical reactivity of heme proteins. Int J Quantum Chem. 2002;90:1505–1514. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rovira C, Kunc K, Hutter J, Ballone P, Parrinello M. Equilibrium structures and energy of iron-porphyrin complexes. A density functional study. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:8914–8925. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crespo A, Scherlis DA, Marti MA, Ordejon P, Roitberg AE, Estrin DA. A DFT-based QM-MM approach designed for the treatment of large molecular systems: Application to Chorismate Mutase. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:13728–13736. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phillips GN, Jr, Teodoro ML, Li T, Smith B, Olson JS. Bound CO is a molecular probe of electrostatic potential in the distal pocket of myoglobin. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8817–8829. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Badger RM. The relation between the internuclear distances and force constants of molecules and its application to polyatomic molecules. J Chem Phys. 1935;3:710–714. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green MT. Application of Badger’s rule to heme and non-heme iron-oxygen bonds: an examination of ferryl protonation states. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1902–1906. doi: 10.1021/ja054074s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daskalakis D, Varotsis C. Binding and docking interactions of NO, CO and O2 in heme proteins as probed by density functional theory. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:4137–4156. doi: 10.3390/ijms10094137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlitter J. Estimation of absolute and relative entropies of macromolecules using the covariance matrix. Chem Phys Lett. 1993;215:617–621. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Capece L, Marti MA, Bidon-Chanal A, Nadra A, Luque FJ, Estrin DA. High pressure reveals structural determinants for globin hexacoordination: Neuroglobin and myoglobin cases. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2009;75:885–894. doi: 10.1002/prot.22297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris SA, Gavathiotis E, Searle MS, Orozco M, Laughton CA. Cooperativity in drug-DNA recognition: a molecular dynamics study. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12658–12663. doi: 10.1021/ja016233n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukai M, Savard PY, Ouellet H, Guertin M, Yeh SR. Unique ligand-protein interactions in a new truncated hemoglobin from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3897–3905. doi: 10.1021/bi0156409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Das TK, Couture M, Ouellet Y, Guertin M, Rousseau DL. Simultaneous observation of the O—O and Fe—O2 stretching modes in oxyhemoglobins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:479–484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li T, Quillin ML, Phillips GN, Jr, Olson JS. Structural determinants of the stretching frequency of CO bound to myoglobin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1433–1446. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li XY, Spiro TG. Is bound carbonyl linear or bent in heme proteins? Evidence from resonance Raman and infrared spectroscopic data. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:6024–6033. doi: 10.1021/ja00226a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vogel KM, Kozlowski PM, Zgierski MZ, Spiro TG. Role of the axial ligand in heme---CO backbonding; DFT analysis of vibrational data. Inorg Chim Acta. 2000;297:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu N-T, Kerr EA. In: Biological Applications of Raman Spectroscopy: Resonance Raman Spectra of Hemes and Metalloproteins. Spiro TG, editor. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1988. pp. 39–95. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phillips GN, Jr, Teodoro ML, Li T, Smith B, Gilson MM, Olson JS. Bound CO is a molecular probe of electrostatic potential in the distal pocket of myoglobin. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8817–8829. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson JB, Lamb DC, Frauenfelder H, Müller JD, McMahon B, Nienhaus GU, Young RD. Ligand binding to heme proteins. VI Interconversion of taxonomic substates in carbonmonoxymyoglobin. Biophys J. 1996;71:1563–1573. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79359-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merchant KA, Noid WG, Thompson DE, Akiyama R, Loring RF, Fayer MD. Structural assignments and dynamics of the A substates of MbCO: Spectrally resolved vibrational echo experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeh SR, Couture M, Ouellet Y, Guertin M, Rousseau DL. A cooperative oxygen binding hemoglobin from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Stabilization of heme ligands by a distal tyrosine residue. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1679–1684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pesce A, Nardini M, Ascenzi P, Geuens E, Dewilde S, Moens L, Bolognesi M, Riggs AF, Hale A, Deng P, Nienhaus GU, Olson JS, Nienhaus K. Thr-E11 regulates O2 affinity in Cerebratulus lacteus mini-hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33662–33672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marti MA, Capece L, Bikiel DE, Falcone B, Estrin DA. Oxygen affinity controlled by dynamical distal conformations: The soybean leghemoglobin and the Paramecium caudatum hemoglobin cases. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2007;68:480–487. doi: 10.1002/prot.21454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kundu S, Hargrove MS. Distal heme pocket regulation of ligand binding and stability in soybean leghemoglobin. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 2003;50:239–248. doi: 10.1002/prot.10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Springer BA, Sligar SG, Olson JS, Phillips GN., Jr Mechanisms of ligand recognition in myoglobin. Chem Rev. 1994;94:699–714. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.