Abstract

Aim

Drug addiction is a chronic brain disease with constant relapse requiring long-term treatment. New pharmacological strategies focus on the development of an effective anti-relapse drug. This study examines the effects of levo-Tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP) on reducing heroin craving and increasing the abstinence rate among heroin-dependent subjects

Methods

One hundred twenty heroin-dependent subjects participated in the randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled study using l-THP treatment. The participants remained in a ward during a four-week period of l-THP treatment, followed by four weeks of observation after treatment. Subjects were followed for three months after discharge. Outcome measures are the measured severity of the protracted abstinence withdrawal syndrome (PAWS) and the abstinence rate.

Results

Four weeks of l-THP treatment significantly ameliorated the severity of PAWS—specifically, somatic syndrome, mood states, insomnia, and drug craving, in comparison to the placebo group. Based on the three-month follow-up observation, participants who survived the initial two weeks of the l-THP medication and remained in the trial program, had a significantly higher abstinence rate of 47.8% (95% CI: 33-67%) than those of 15.2 % in the placebo group (95% CI:7-25%), according to a log-rank test (P < 0.0005).

Conclusion

l-THP significantly ameliorated PAWS, especially reduced drug craving. Furthermore, it increased the abstinence rate among heroin users. These results support the potential use of l-THP for treatment of heroin addiction.

Keywords: Heroin addiction, l-Tetrahydropalmatine, Abstinence rate, Relapse

Introduction

Drug addiction, a chronic brain disease, is characterized by constant relapse that requires long-term treatment[1]. Currently, the first line of treatment for the chronic opioid dependence is agonist maintenance treatment, such as methadone and buprenorphine. The principle of maintenance treatment is to suppress withdrawal symptoms and heroin craving, reducing heroin abuse and the risks associated with drug use behaviors[2,3]. Fundamentally, however, the maintenance treatment is not an abstinence-oriented program. Once the maintenance program is interrupted, the protracted abstinence withdrawal syndrome (PAWS) will occur, resulting in relapse.

New pharmacological strategies that target specific elements of the addiction cycle are currently under intense investigation. For example, naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist, was initially developed to treat heroin dependence by blocking euphoria and weakening the addiction cycle. In clinical practice, however, naltrexone produced adverse effects and did not ameliorate the PAWS of opiate dependence, resulting in lower retention rate and relapse[4]. So far, pharmacological agents have shown limited efficacy in the treatment of drug addiction[5]. There are no broadly effective anti-relapse pharmacotherapies available for human opiate dependence.

The major problem in the clinical treatment of drug dependence is relapse. Many addicts respond very well to inpatient treatment and yet their relapse occurs soon after leaving the program. The addiction neurobiology, based on decades of animal studies, suggests that the onset of heroin withdrawal coupled with reward deficits could play a critical role in provoking craving and relapse in human opiate addicts[6]. We hypothesized that if a medication, without reinforcing abuse potential, could effectively ameliorate the PAWS of opiate dependence, especially the drug craving, the medication could be effective in reducing the relapse rate. To test this hypothesis, we employed rotundine, i.e., l-Tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP), in this pilot study.

l-THP is a main active ingredient of a Chinese traditional analgesic herb, and has been safely prescribed in Chinese clinical settings for more than 40 years. l-THP significantly binds to dopamine (D1, D2, and D3) receptors[7-12], and antagonizes morphine abuse in animal experiments[13-15]. Recent reports showed the D3 to be significantly involved in drug craving and relapse processes[16-18]. Further, l-THP has no abuse potential and its pharmacology and neuropsychomarmacology have been extensively studied with animals and human models. These results have been widely published, particularly in Chinese literature[19]. Finally, since l-THP is already listed in Chinese pharmacopeia, the associated costs and time required to conduct clinical trials would be substantially reduced.

At present, we report our initial results in a randomized, placebo-controlled and double-blinded study with l-THP treatment after seven to 10 days of detoxification. We demonstrate that l-THP treatment significantly ameliorates PAWS, especially drug craving, and increases abstinence rate among heroin users.

Materials and Methods

l-THP

l-THP is a purified compound isolated from Chinese herbs by Best & Wide Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, City of Nanning, Guangxi Province, China. It has been approved by the Chinese government agency since 1964 (State Food and Drug Administration of China), listed in Pharmacopoeia of China (1977 edition) for human use in relief of chronic pain, insomnia, and anxiety.

Human Subjects

One hundred twenty heroin-dependent subjects (27.57±5.76 years old, mean ± standard deviation, 89 males and 29 females) were recruited during the study period between June 2000 to February 2001 from the inpatient population of Hengyang Detoxification Clinic (HDC), Hunan, China. Each participant met the DSM-IV criteria for heroin dependence and tested as having a positive opiate in his or her urine test before entering the HDC. These subjects expressed their willingness to participate in this trial. Exclusion criteria included the following: any drug dependence other than tobacco and opiates; history of psychiatric and neurological diseases such as schizophrenia, psychosis, past seizure episode, or current use of psychoactive medications; hepatic, cardiovascular, and renal diseases; and pregnancy or breastfeeding. A written informed consent was obtained from each subject and the human protocol was approved by the IRB of Second Xiangya Hospital.

Study Design

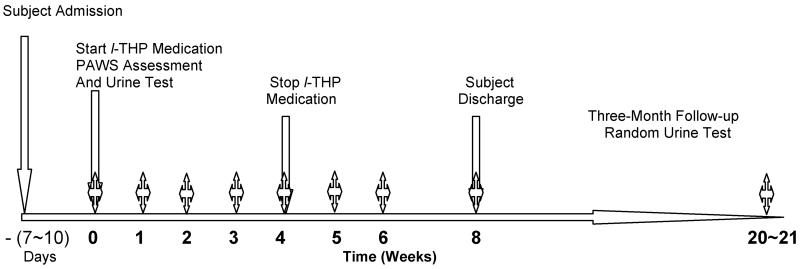

A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was designed. As shown in Fig. 1, participants had been detoxified on a ward in the HDC and were abstinent for at least seven days before entering the trial. The participating subjects remained in a ward during this trial. Participants were randomly divided into two groups: the l-THP treatment group (orally take two tablets each time and each tablet has 30 mg l-THP, two times per day) and the placebo group (two placebo tablets, two times per day). The treatment dose was selected based on the preclinical and clinical studies in order to minimize its mild sedative effects, which begin to manifest at a higher dose (>100 mg/70 kg body eight). The l-THP and the placebo tablets were provided by Best & Wide Pharmaceutical. The l-THP medication lasted for one month, while participants stayed in the clinic as inpatients. After cessation of l-THP treatment for one month, participants either stayed in the clinic or decided to return home. Urine samples were collected to test for heroin or morphine by eight different intervals: day of admission, day 7, 14, 21, and 28 during the l-THP medication, and at day 5, 14, and 28 after cessation of the medication. During the following three months after subjects were discharged, the random urine tests were conducted to check their abstinence-free status for the residual of heroin or morphine. During the five-month study period, participants could discontinue the study at any time. No subject received psychotherapy. PAWS severity was determined by completing a questionnaire at the eight time intervals, as described above.

Fig. 1.

Experimental Design and the time courses of the randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled l -THP trial program. The symbol  indicates the time intervals at which the PAWS assessments and urine tests were conducted.

indicates the time intervals at which the PAWS assessments and urine tests were conducted.

The questionnaire measuring the severity of the PAWS, termed Heroin Withdrawal Scale (HWC), was specifically developed and validated for opiate dependence[20]. As listed in Table 2, this self-rating scale consists of 30 symptoms in four categories: nine symptoms in the mood category, eight symptoms in the craving category, four symptoms in the insomnia category, and nine symptoms in the somatic category. The intensity of each symptom was rated with five-point scale of (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely). The rated scores for each symptom in the same category from a subject were added up as the categorized score for the subject. Then, the categorized scores from individual subjects in a group were averaged to obtain the means and standard deviations. The higher the scores were, the more severe the PAWS.

Table 2.

A list of 30 symptoms of the protracted abstinence withdrawal syndrome to be subjectively rated by participating human subjects on a 5-point scale of (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely.)

| Categories | Protracted Abstinence Withdrawal Symptoms |

| Somatic | 1)Get goose flesh; 2)Have hot and cold flashes; 3)Running nose and tearing eyes; 4)Nose and throat are choked; 5)Muscles and joints aching; 6)Muscles twitching; 7)Whole body discomfort; 8)Yawning; 9)Feel ill |

| Mood | 1)Feel lonely; 2)Do not like to talk and hate to be disturbed; 3)Nothing seems interesting; 4)Hard to focus attention; 5)Feel bored and not wanting to do anything; 6)Feel distracted; 7)Feel hyperirritable; 8)Agonizing; 9)Restless |

| Insomnia | 1)Wake up early in the morning; 2)Hard to fall asleep at night; 3)No deep sleep and wake up often; 4)Have dreams often |

| Heroin Craving |

1)Want to take drugs when thinking of conditioned cues; 2)Craving for drugs when facing conditioned cues; 3)Always thinking about take drugs; 4)Want to take drug while bored; 5)Want to take drug while having sleep troubles; 6)No drugs, life is boring; 7)No drugs, days wear on like years; 8)No drugs, feel lost. |

The endpoints of the study

Retention in treatment and abstinence rates were employed as the endpoints. No information was collected from those who left the trial program. These subjects were categorized as “relapsed” when determining the abstinence rate. Other outcome measures included changes in PAWS severity scores (HWC-30) for mood, craving, sleep and somatic symptoms. The higher the scores, the more severe the syndrome.

Data Analysis

The Kalan-Meier method was employed to estimate the event-free survival probability of subject retention in the treatment program, and the log-rank test was used to analyze the retention rate between the l–THP-treated group and the placebo group. Considering the effects of antagonistic mechanisms of the l-THP treatment on the mood syndrome, the estimations were conducted in two time periods: the first was done in the initial two weeks and the other was accomplished in the rest of trial period. The differences in severity among the PAWS scores, and the individual PAWS categorical ratings for “somatic,” “mood,” “sleeping” and “craving” were analyzed with the following time-dependent regression model:

where tk,i,j = (0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 56 days) are observation times, Yk,i,j is the jth measurement of the ith subject from kth treatment group, and εk,i,j are the zero mean error terms. The testing null and alternative hypotheses are

The differences in severity scores of PAWS measurements between treated and placebo groups were assessed using the method of comparing cross-section growth data[21,22]. This method compares the difference of the areas under the regression curves (i.e. it examines whether there is an overall difference between the two groups). When a significant difference is detected, the student t-test method can be used to identify differences at a given time point.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics of participating subjects

Table 1 lists the demographics and clinical characteristics of the participants taken from the Selected Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV diagnoses at intake. None of the variables differed in terms of sex, age, education, the kind of treatment, the age of onset, and the daily time of heroin administrated between the l-THP treated group and placebo group. No significant differences were evident in these demographics between the two groups.

Table 1.

A list of demographics and clinical characteristics of participating subjects.

| Groups | Placebo | l-THP |

|---|---|---|

| N | 61 | 59 |

| Age(Mean ± SD years) | 27.5 ± 5.9 | 27.7 ± 5.6 |

| Gender(M/F) | 46/15 | 45/14 |

| Education (Mean ± SD years) | 8.4 ± 2.4 | 8.5 ± 2.2 |

| Employment status (Employment /Unemployment) |

18/41 | 22 /35 |

| Type of drug (heroin/other drug) | 58/2 | 58/1 |

| Age of opiate intake onset (Mean ± SD years) |

24.4 ± 5.1 | 24.2 ± 5.0 |

| Times of daily heroin intake (Mean ± SD) |

2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.6 |

Comparison of the dropout rates and abstinence rates after the l-THP medication

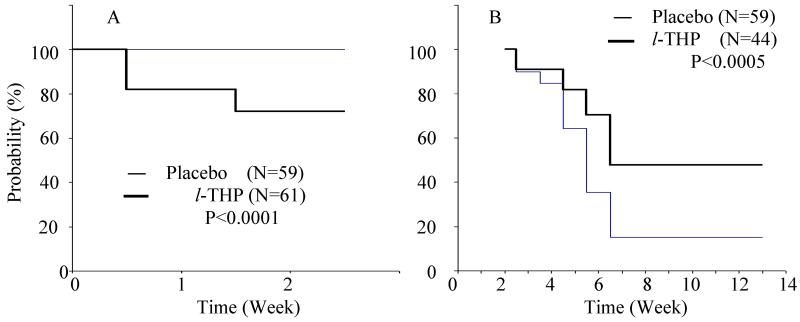

The results of the retention for the l-THP treated and placebo groups were shown in Fig. 2 by the Kaplan-Meier estimators. After medication for two weeks, the survival probability of retention for the placebo group is 100 (100-100)%, while that of the l-THP-treated group is 72 (60-83)%. The numbers in the parenthesis represent the 95% confidence interval (CI). The log-rank test showed that the dropout rate for the l-THP-group was significantly higher than that of the placebo group (Fig. 2A, Table 3, P<0.0001 ). The placebo group retained 59 subjects in the trial program, whereas the medication group decreased from 61 subjects to 44 (Fig. 2A Table 3).

Fig. 2.

(A) Event-free survival probability among subjects not dropping out during the first 14 days of the l-THP treatment. The subjects in the placebo group have a significantly higher retention rate than those in the l-THP treatment group (P<0.0001). (B) A Kaplan-Meier Curve of subjects during the treatment period. Those subjects who survived after the first 14 days treatment (Placebo treatment with 59 subjects and l-THP treatment with 44 subjects) served as the baseline when after three months calculating the survival probability. The abstinent rate in the l-THP treatment group (21 subjects) is significantly higher than that of the placebo group (9 subjects, P<0.0005).

Table 3.

Comparison of total scores (the summation of the four categories) of the Protracted Abstinence Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS) between Placebo and l-THP treated groups. The time-dependent regression model revealed that the l-THP treated group had significantly ameliorated total PAWS scores than the placebo group (Z=−9.73, P<0.0001).

| Day | Placebo Group N |

l–THP Group N |

PAWS Placebo Mean ± SE |

PAWS l-THP Mean ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start Medication |

59 | 61 | 41.72±2.27 | 41.61±2.79 |

| Week 0 | ||||

| Week 1 | 59 | 50 | 36.64±1.75 | 31.02±2.21 |

| Week 2 | 59 | 44 | 29.56±1.54 | 26.77±1.92 |

| Week 3 | 53 | 40 | 27.98±1.49 | 25.75±1.79 |

| Week 4 | 50 | 40 | 25.26±1.47 | 23.00±1.91 |

| Follow-up after medication |

||||

| Week 5 | 38 | 35 | 23.71±2.00 | 17.36± 1.59 |

| Week 6 | 21 | 31 | 17.86±2.45 | 13.39± 1.64 |

| Week 8 | 9 | 21 | 14.67± 2.06 | 12.10± 1.80 |

| 3 Months | 9 | 21 | Negative urinalyses | |

SE, Standard Error.

After the three-month follow-up observation, it was noted that participants who survived the two weeks of medication and remained in the trial program had a high abstinence rate of 47.7% (95% CI: 33-67%), as opposed to the placebo group of 15.2 % (95% CI:7-25%). The log-rank test has a P value of 0.0005, indicating that the abstinence rate is significantly higher in the treatment group than the placebo group (See Fig. 2B).

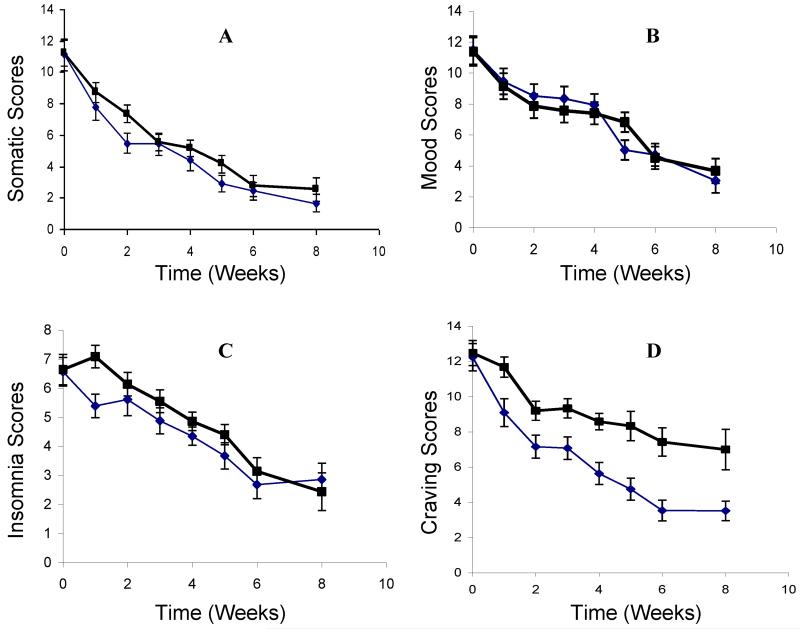

Effects of the l-THP medication on total scores and the four categories of the PAWS

According to the regression analysis, one month of l-THP medication significantly reduced the total scores of the PAWS severity, as shown in Table 3. (Z=−9.73; P<0.0001). The l-THP treated group showed significant reduction in severity than the placebo group in the somatic syndrome, (Fig. 3A, Z=−6.082; P<0.0001), insomnia (Fig. 3C, Z=−6.399; P < 0.0001) and craving Fig. 3D, Z=−22.42; P<0.0001), but not in the mood state (Fig. 3B, Z=0.2568; P = 0.7973)

Fig. 3.

The time courses of subjective rating scores of the categorized protracted abstinence withdrawal syndromes (PAWS). The time courses of the somatic syndromes (Z=−6.082) (A), the mood syndromes (Z= 0.257) (B), insomnia (Z=−6.399) (C), and craving (Z=−22.42) (D) between the placebo and l-THP treatment groups were compared and the significant levels were expressed with Z-scores. The bars represent the standard errors. The bold lines represent the placebo group and the thin lines the l-THP treatment group.

The most intriguing result of the l-THP treatment was the significant reduction in opiate craving (Fig. 3D). After one week of treatment with l-THP, the craving scores were substantially reduced compared to the placebo group, and continued to decline thereafter. One month after the cessation of treatment, the craving score was 3.5±2.6 (Mean±SD) for the treatment group, versus 7.0±3.5 for the placebo group (P<0.01, Fig. 3D).

Discussion

l-THP has an anti-relapse effect

The present study supported a clinical hypothesis that continued treatment is necessary beyond detoxification, even when the body is cleansed of the drug. Our experimental results demonstrated that l-THP medication can significantly reduce the severity of PAWS, especially the opiate craving, and increase the abstinence rate after medication. Our preliminary results demonstrated that proper medication, such as l-THP could be effective in decreasing opiate relapse.

The present study design has a unique feature in that the administration of l-THP was given after seven to 10 days of drug abstinence. Since the main goal of this study is to test if l-THP is effective as an anti-relapse medication, it is necessary to have subjects achieve a drug-free state first, at least for a period of time, then determine the relapse rate from the drug-free state. There was difficulty in ascertaining the ideal length of the drug-free state. It is noteworthy that in the Kaplan-Meier curves in Fig. 2A, the retention rate was significantly lower during the first two weeks of l-THP treatment, as opposed to the placebo group. On the other hand, the treatment retention rate improved after 14 days of l-THP medication, as shown in Fig. 2B. It is denoted that a period of drug-free state requires at least a 2 week trial period of l-THP. The detailed mechanisms underlying the lower retention rate in the first two weeks are not clear. Among these unscheduled early termination cases, there were no reports of adverse effects or acute hepatic toxicity due to the l-THP treatment. The effects of the dopaminergic antagonisms of the l-THP could have played a role in early discharge. A previous study suggested that chronic heroin users might produce a reduction in dopaminergic activity in the human brain[18]. The antagonisms of l-THP medication could reduce the postsynaptic dopaminergic activities further, resulting in lower retention. This mechanism may be similar to that evidenced in clinical practice where naltrexone treatment may not give to heroin users until subjects have a negative reaction to naloxone. This is because endogenic opioid peptides, such as endophine and enkephalin, have downregulated and have not recovered in a short drug-free period. It is hypothesized that once the endogenic opioid peptides are recovered and l-THP treatment enhances dopamine activity, the dropout rate will be reduced. This hypothesis is supported by two facts. First, after two weeks of l-THP treatment, the retention rate in subjects improved significantly, as shown in Fig. 2B. Second, the l-THP treatment enhanced the presynaptic dopaminergic activity and release of dopamine via the feedback regulation, as shown in animal models [38-40].

Since the main goal of this study is to test if l-THP is effective as an anti-relapse medication, it is necessary that subjects achieve a long drug-free state first, followed by l-THP treatment to prolong the heroin abstinence. Based on this observation, it is suggested that subjects be tested 21-30 days before the l-THP medication, rather than the current 7-10 days. This should allow a higher retention rate during the early treatment period.

The possible mechanism of l-THP treatment for heroin abstinence

First, l-THP is an antagonist of DA receptors[7-11]. Its antagonistic effect on DA receptors, particularly presumed by D2 and D3 receptors, would play an important role in reducing the drug craving. Many recent studies in animal models have demonstrated that l-THP is a potential candidate for treating heroin addiction[12-15] and cocaine addiction[23-25]. Other studies showed that D3 receptor antagonism significantly inhibits cocaine-seeking behaviors[26-28] and reduces nicotine-paired environmental cue functions [29].

The D2-like DA (D2 and D3) receptors display a presumed pharmacological similarity and homology in sequence of amino acids, which have been increased up to 75% in the seven transmembrane domains. It has been shown that D3 receptors are mainly located postsynaptically, and a subset of D3 receptors is located presyneptically. The neuroanatomical locations of D3 receptors are mainly restricted to expression in distinct areas of the limbic system, such as the nucleus accumbens, and the islands of Calleja. The nucleus accumbens is involved in the diverse neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia and drug abuse (heroin, morphine, cocaine etc.), which have been extensively reviewed[16,30].

Secondly, it has been shown that the antinociception of l-THP is based on the antagonism on the D2 and D3 DA receptors in the VTA - accumbens nucleus - prefrontal cortex DA pathway[19]. And the D2 receptors in the arcute nucleus of hypothalamus is also involved in l-THP-induced, ß-endorphin neurons mediated analgesic action[19,31], which projects to periaqueductal grey (PAG), an important action site of morphine. It has been observed that l-THP acted on the arcute nucleus and had a sequential enhancement of END release, which modulates the physiological functions, such as analgesic or anti-crave resulting from the long-time exposure of morphine[32,33]. Besides, D2 and D3 antagonism of l-THP would interrupt the DA transporter function in the nucleus accumbens on the pre- and post-synaptic sites[11,34,35].

Furthermore, brain DA neurons in the heroin addicts may become maladapted due to long-term exposure to morphine and could be readapted by the l-THP treatment. In the experiment of morphine-dependent rats, the levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in the DA neurons of ventral tegmental area (VTA) were significantly increased. l-THP treatment significantly decreased the levels of GFAP and TH in the VTA region to normal levels, indicating that the function of the dopaminergic neurons is in recovery[36]. Similarly, the l-THP treatment can reverse the decreases of dopamine D1- and D2-receptor mRNAs in morphine-dependent rats[37]. These results suggest that l-THP treatment can facilitate the recovery of dopaminergic functions and gene expression.

Recent studies demonstrated that l-THP treatment could produce a rightward and downward shift in the dose-response curve for cocaine self administration and attenuated cocaine-induced reinstatement [23,24]. It is presumed that the cocaine-induced, DA transporters-mediated effect is reduced by the D2 and D3 antagonism of l-THP on the post-synaptic site in the nucleus accumbens, which may be potentially of use in treating human cocaine addiction.

Limitations of this pilot study

This pilot study demonstrated that l-THP significantly ameliorated PAWS, especially reducing drug craving and increasing the abstinence rate among heroin users. These results support the potential use of l-THP for treatment of heroin addiction. However, there were several methodological limitations to be addressed. First, study participants were mixed between treatment seekers and nontreatment seekers, since they were recruited from the compulsory detox institution. It is possible that treatment seekers and nontreatment seekers may have different responses to l-THP treatment. Second, the present study employed only pharmacotherapy with l-THP medication without cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT). It is expected that the combination of CBT with pharmacotherapy may produce a synergistic effect. Third, the present study has been limited to employing only one dose of l-THP with a short duration (one month). Although the short duration and the low dose of l-THP were initially chosen to reduce the risk of possible hepatic toxicity [41], a future study may examine effects of the length of treatment time, number of treatment sessions, and dose responses.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology grant 2003CB51540 and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA10214. We thank Dr. Gaohong Wu and Mr. Douglas Ward for statistical analysis, and Ms. Carrie O’Connor for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

No authors of this paper have any possible conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, related directly or indirectly to the submitted work.

References

- 1.O’Brien CP. Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: a possible new class of psychoactive medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1423–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haasen C, van den Brink W. Innovations in agonist maintenance treatment of opioid-dependent patients. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:631–636. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000245759.13997.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung S, Conry JM. Role of buprenorphine in the management of heroin addiction. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:501–505. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dackis C, O’Brien C. Neurobiology of addiction: treatment and public policy ramifications. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1431–1436. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidbreder CA, Hagan JJ. Novel pharmacotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of drug addiction and craving. Current Opinion in Pharmacol. 2005;5:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenny PJ, Chen SA, Kitamura O, Markou A, Koob GF. Conditioned withdrawal drives heroin consumption and decreases reward sensitivity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5894–5900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0740-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu SX, Yu LP, Han YR, Chen Y, Jin GZ. Effects of tetrahydroprotoberberines on dopamine receptor subtypes in brain. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 1989;10:104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin GZ. (−)-Tetrahydropalmatine and its analogues as new dopamine receptor antagonists. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1987;8:81–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin GZ, Wang XL, Shi WX. Tetrahydroprotoberberine - a new chemical type of antagonist of dopamine receptors. Scientia Sin [B] 1986;29:527–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin GZ, Xu SX, Yu LP. Different effects of enantiomers of tetrahydropalmatine on dopaminergic system. Scientia Sinica [B] 1986;29:1054–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y. The pharmacological properties of l-stepholidine on different dopamine receptor subtypes. Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica. Chinese Academy of Sciences; Jun, 2005. pp. 14–28. Thesis of PhD, Supervisor: Prof Jin G-Z and Shi W-X. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong Z, Fan G, Le J, Chai Y, Yin X, Wu Y. Brain pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of tetrahydropalmatin enantiomers in rats after oral adminstration of the recemate. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2006;27:111–117. doi: 10.1002/bdd.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YB, Ren YH, Zheng JW, Zeng I. Influence of l-tetrahydropalmatine on morphine-induced conditioned place preference. Chinese Pharmacol Bull. 2005;21:1442–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang YB, Ren YH, zheng JW. The effects of l-THP on morphine-induced discrimination. Chinese Journal of Drug Dependence. 2005;14:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu YL, Liang JH, Yan LD, Su RB, Wu CF, Gong ZH. Effect of l-tetrahydropalmatine on locomotor sensitization to oxycodone in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:533–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidbreder CA, Gardner EL, Xi ZX, Thanos PK, Mugnaini M, Hagan JJ, Ashby CR., Jr. The role of central dopamine D3 receptors in drug addiction: a review of pharmacological evidence. Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:77–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilla M, Perachon S, Sautel F, Garrido F, Mann A, Wermuth CG, Schwartz JC, Everitt BJ, Sokoloff P. Selective inhibition of cocaine-seeking behaviour by a partial dopamine D-3 receptor agonist. Nature. 1999;400:371–375. doi: 10.1038/22560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kish SJ, Kalasinsky KS, Derkach P, Schmunk GA, Guttman M, Ang L, Adams V, Furukawa Y, Haycock JW. Striatal dopaminergic and serotonergic markers in human heroin users. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:561–567. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin GZ. Discoveries in the voyage of corydalis research. Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers; 2001. pp. 15–68.pp. 92–141.pp. 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HX, Hao W, Yang DS. The development of subjective protracted withdrawal scales for opiate dependence. Chin J Mental Health. 2003;17(5):294–297. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheike TH, Zhang MJ. Cumulative regression function tests for regression models for longitudinal data. The Annals of Statistics. 1999;26:1328–1355. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheike TH, Zhang MJ, Juul A. Comparing reference charts. Biometrical J. 1999;41:679–787. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo JS, Ren YH, Zhu R. The effect of l-THP on cocaine-induced conditioned position preference. Chin J Drug Depend. 2003;12:177–179. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantsch JR, Li S-J, Risinger R, Awad S, Katz E, Baker DA, Yang Z. Levo-tetrahydropalmatine attenuates cocaine self-administration and cocaine-induced reinstatement in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:581–591. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi ZX, Yang Z, Li SS, Li X, Dillon C, Pang XQ, Spiller K, Gardner EL. Levo-tetrahydropalmatine inhibits cocaine’s rewarding effects: Experiments with self administration and brain-stimulation reward in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53(6):771–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vorel SR, Ashby CR, Jr, Paul M, Liu X, Hayes R, Hagan JJ, Middlemiss DN, Stemp G, Gardner EL. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:9595–9603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xi Z-X, Gilbert J, Campos AC, Kline N, Ashby CR, Jr, Hagan JJ, Heidbreder CA, Gardner EL. Blockade of mesolimbic dopamine D3 receptors inhibits stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2004;176:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1858-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xi Z-X, Newman AH, Gilbert JG, Pak AC, Peng XQ, Ashby CR, Jr, Gitajn L, Gardner EL. The novel dopamine D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 inhibits cocaine’s rewarding effects and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1393–1405. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pak AC, Ashby CR, Jr, Heidbreder CA, Pilla M, Gilbert J, Xi Z-X, Gardner EL. The selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonist SB-277011A reduces nicotine-enhanced brain reward and nicotine-paired environmental cue functions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9:585–602. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joyce JN, Millan MJ. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as therapeutic agonis. Drug Dis Today. 2005;10:917–925. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu JY, Jin GZ. Supraspinal D2 receptor involved in antinociception induced by l-tetrahydropalmatine. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2000;21:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu J-Y, Jin G-Z. Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus involved in analgesic action of l-THP. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2000;1:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ge X-Q, Lin A-P, Sun Y, Zhou H-Z, Zhang H-Q, Bian C-F. Effects of l-tetrahydropalmatine on opioid peptides contents in morphine dependent rats. Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin. 2001;17:264–266. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y-L, Liang J-H, Yan L-D, et al. Effects of l-tetrahydropalmatine on locomotor sensitization to oxycodone in mice. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2005;26(5):533–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Zhou Y, Sun J, et al. The effect of l-stepholidine, a novel extract of Chinese herb, on the acquisition, expression, maintenance, and re-acquisition of morphine conditioned place preference in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52(2):356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Z, Li CO, Fan M. Effect of tetrahydroprotoberberines on contents of glial fibrillary acidic protein and tyrosine hydroxylase in ventral tegmental area of morphine dependent rats. Chin J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;17:246–250. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z, Li CQ, Fan M. Effects of tetrahydroprotoberberines on expression of dopamine system related genes in morphine dependent rats. Chin J Psychiatry. 2004;37:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcenac F, Jin GZ, Gonon F. Effect of l-tetrahydropalmative on dopamine release and metabolism in the ret striatum. Psychopharmcology. 1986;89:89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00175196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang KX, Sun BC, Gonon F, Jin GZ. Effects of tetrahydroprotoberberines on dopamine release and 3,4-dihydroxyphenglacetio acid level in corpus striatuns measuced by in vivo voltammetry. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 1991;12:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen LJ, Guo X, Wang QM, Jin GZ. Feed-back regulation of presynaptic D2 receptors blockaded by l-stepholidive and l-tetrahydropalmatine. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 1992;13:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai C-K, Chan AY-W. Tetradropalmatine Poisoning:Diagnoses of Nine Adult Overdoses Based on Toxicology Screens by HPLC with Diode-Array Detection and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry. 1999;45(2):229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]