Abstract

Several ultrasound-based imaging modalities have been proposed for image guidance and monitoring of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) treatment. However, accurate localization and characterization of the effective region of treatment (focal spot) remain important obstacles in the clinical implementation of HIFU ablation. Harmonic Motion Imaging for Focused Ultrasound (HMIFU) is a HIFU monitoring technique that utilizes radiation-force-induced localized oscillatory displacement. HMIFU has been shown to correctly identify the formation and extent of HIFU thermal ablation lesions. However a significant problem remains in identifying the location of the HIFU focus, which is necessary for treatment planning. In this study, the induced displacement was employed to localize the HIFU focal spot inside the tissue prior to treatment. Feasibility was shown with two separate systems. The 1D HMIFU system consisted of a HIFU transducer emitting an amplitude-modulated HIFU beam for mechanical excitation and a confocal single-element, pulse-echo transducer for simultaneous RF acquisition. The 2D HIFU system consists of a HIFU phased array, and a co-axial imaging phased array for simultaneous imaging. Initial feasibility was first performed on tissue-mimicking gelatin phantoms and the focal zone was defined as the region corresponding to the −3 dB full width at half maximum of the HMI displacement. Using the same parameters, in vitro experiments were performed in canine liver specimens to compare the defined focal zone with the lesion. In vitro measurements showed good agreement between the HMI predicted focal zone and the induced HIFU lesion location. HMIFU was experimentally shown to be capable of predicting and tracking the focal region in both phantoms and in vitro tissues. The accuracy of focal spot localization was evaluated by comparing with the lesion location in post-ablative tissues, with a R2 = 0.821 at p<0.002 in the 2D HMI system. We demonstrated the feasibility of using this HMI-based technique to localize the HIFU focal spot without inducing thermal changes during the planning phase. The focal spot localization method has also been applied on ex vivo human breast tissue ablation and can be fully integrated into any HMI system for planning purposes.

Keywords: HMIFU, HIFU, focal spot localization

Introduction

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) was first investigated as a non-invasive therapeutic technique in the 1940s to produce thermal lesions in living animals (Lynn et al., 1942). The objective of HIFU is to thermally coagulate tissue at the focus of the transducer through application of high intensity acoustic beams. The HIFU beam is finely focused on a small region of the tissue and produces rapid and intense heating. Over the past several decades, HIFU has been increasingly explored as an extracorporeal modality to ablate tumors in cancer treatment, but is only recently beginning to emerge as a vital alternative to conventional therapies (Illing et al., 2005; Kennedy et al., 2004).

Treatment planning constitutes one of the most critical aspects of HIFU treatment. Correct placement of the HIFU beam is critical to avoid unnecessary, thermal damage in normal tissues. The targeting step is essential because the apparent focal spot can be shifted from the geometric focus due to phase aberrations caused by tissue inhomogeneities (O'Donnell and Flax, 1988). To this end, many researchers have been developing techniques and methods for HIFU treatment planning. As of now, HIFU treatment planning and real-time monitoring are performed by two major imaging modalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound imaging. During the planning stage of MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) treatment, a small temperature increment is generated at the focal spot. MR thermometry is used to generate a quantitative temperature map of tissues and detects the focal spot with a small temperature elevation as low as 1°C (Bohris et al., 1999; Chung et al., 1996). MR acoustic radiation force imaging (MR-ARFI) has previously been proposed to locate the beam using tissue displacement map at low intensities to avoid heat deposition in the target during planning (McDannold and Maier, 2008; Kaye et al., 2011; Auboiroux et al., 2012). Despite its advantages, MRgFUS still relies on a high-cost hybrid system and has relatively low temporal resolution. Compared to MRI, ultrasound itself is a low-cost imaging modality offering several advantages, including high temporal resolution and lower compatibility requirements. Conventional B-mode has been found to be capable of detecting hyperechoic regions due to cavitation and/or boiling at the focus but these phenomena are by definition random and unreliable especially after HIFU cessation (Vaezy et al., 2001). Ultrasound-based temperature mapping relies on the temperature dependence of the speed of sound in tissues, which increases with temperature between 37°C and 50°C in non-fatty tissues (Bamber and Hill, 1979; Seip and Ebbini, 1995; Simon et al., 1998; Sehgal et al., 1986). However, the limitation of ultrasound-based temperature measurements lies in the fact that the linear relationship between the speed of sound and temperature is no longer valid at temperatures above 50°C or higher. Vaezy et al. aimed at targeting by monitoring the magnitude of RF data around the focal spot. They showed that the focal RF data amplitude increased immediately after starting HIFU (Zheng and Vaezy, 2010). However, it may lose accuracy for in vivo application where motion disturbance is much more significant on a pixel-to-pixel basis.

Our group has developed a radiation-force-based method named Harmonic Motion Imaging for Focused Ultrasound (HMIFU) as a therapy monitoring method with feasibilities demonstrated in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo (Maleke and Konofagou, 2010; Konofagou and Hynynen, 2003). Instead of estimating temperatures or quantification of the backscatter RF signals, HMIFU monitors the localized displacement at the focus as an indicator of the HIFU focal zone placement. HMIFU is a dynamic, all-ultrasound based system for both ablation and imaging, which utilizes a HIFU transducer by emitting an amplitude-modulated (AM) beam to simultaneously thermally ablate and induce a stable oscillatory tissue displacement at its focal zone. The oscillatory response is then estimated by a cross-correlation-based motion tracking technique on the RF signal collected by a confocally-aligned diagnostic transducer. It is based on the radiation force to induce vibration at the focal zone for the detection of localized stiffness changes (Maleke and Konofagou, 2008). The feasibility of HMIFU for HIFU lesion detection based on the underlying tissue elasticity changes was verified in previous studies (Hou et al., 2011).

The main objective in this paper is to study the feasibility of using the HMIFU method to localize the focus of the HIFU beam. To our knowledge, this is the first radiation force based all-ultrasound elastography method designed for focal spot localization, which is also robust to temperature limit and motion artifact. In this study, we will use a 1-D and 2-D based system to assess the feasibility of focal spot localization on phantom, in vitro liver, and ex vivo human breast specimens. We expect HMIFU to detect the focal spots with verifications based on gross histology.

Methods

A. Tissue-mimicking phantom preparation

Phantom experiments were conducted to verify the efficacy of the proposed method. Gelatin powder (Gelatin 50 bloom, MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to construct the tissue mimicking phantoms. Three homogeneous phantoms with elastic modulus of 10 kPa were constructed. The concentration of gelatin powder was 50.7g/L yielding a stiffness of 10 kPa (Krouskop, 1997).

Phantom preparation was completed using the following steps (Hall et al., 1997): 1) gelatin powder was hydrated in a solution of deionized water and isopropanol and heated above its gelling point to disperse the colloid, clarify the solution, and release trapped gasses; 2) the mixture was then placed into an ice waterbath for the purpose of cooling. While the gel solution is liquid, agar powder was added to increase the absorption and the scattering. Note that the agar melted only at temperatures higher than 80°C; thus, it did not significantly contribute to the increase of the phantom stiffness. The mixture was constantly stirred until the temperature decreased to 25°C; 3) and the solution was poured into a mold carefully and placed in a refrigerator overnight.

B. In vitro and ex vivo specimen preparation

Experiments were performed in seven in vitro canine liver specimens on three to six different ablation locations (dependent on the size of the liver) within each specimen. Liver was chosen for the experiment because of its relatively homogenous structure and allowing lesions to be optical contrast in gross pathology. Tissue samples were degassed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature prior to each experiment. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Columbia University as part of a separate study. Human specimen collection and handling of postsurgical breast tissues were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) board of Columbia University and informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients. One normal breast tissue and one invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) ex vivo human tissue specimen were obtained from 2 patients undergoing lumpectomy or mastectomy as part of another separate study. The breast tissue specimens were obtained immediately after surgery and images within 2 hours. In experiments, each specimen was immersed in degased PBS and fixed on an acoustic absorber using metallic needles.

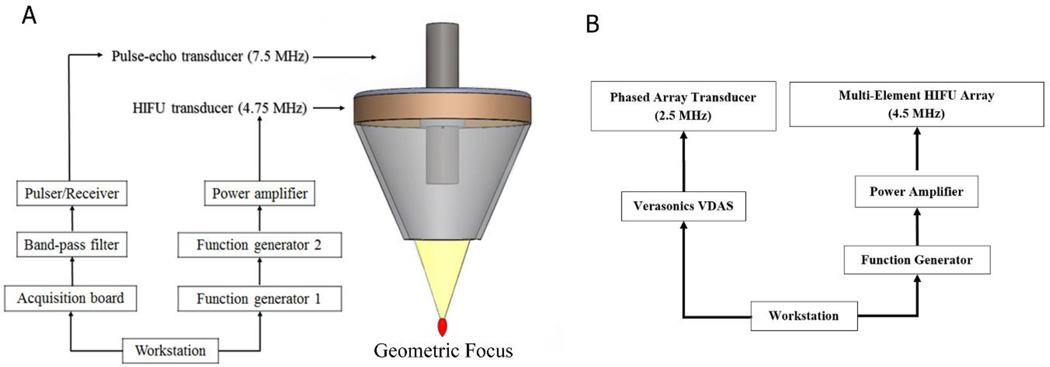

C. 1D HMI setup

The HMI system, as shown in figure 1, was comprised of a 4.755-MHz HIFU transducer (Riverside Research Institute, New York, NY, USA) and a 7.5 MHz single-element transducer (Olympus NDT Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The HIFU transducer (outer diameter = 80 mm, inner diameter = 16.5 mm, focal depth = 90 mm) was used to generate the acoustic force using a low frequency amplitude-modulated RF signal. The −6 dB pressure focal region has an ellipsoidal shape with 7.7 mm in the axial direction and 0.67 mm in the lateral direction. A function generator (33120A, Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to generate a low frequency amplitude modulation waveform at 25 Hz. A second function generator (33220A, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to construct the continuous carrier signal at 4.755 MHz with amplitude modulation using the input from the first function generator. The single-element transducer was driven by a pulser/receiver (5072PR, Olympus, Waltham, MA, USA) with a frame rate at 1000 Hz. RF signals within 10 cm from the transducer surface were recorded using a data acquisition unit (Gage applied, Lockport, IL) at a sampling frequency of 100 MHz. The received RF signals from the pulser/receiver were filtered using an analog band-pass filter (Reactel Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) with cutoff frequencies of fc1 = 5.84 MHz and fc2 = 8.66 MHz.

Figure 1.

(A) 1D HMI experimental set-up. (B) 2D HMI experimental set-up.

D. 2D HMI setup

A 93-element, PZT-4 ceramic focused transducer (individual element diameter = 10 mm, overall out diameter = 110 mm, inner diameter = 41 mm, and focal depth=70 mm. H-178, Sonic Concepts Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) was used for HIFU. The HIFU center opening is designed to always position the imaging array to be confocal with the HIFU transducer focus. All HIFU channels were synchronously excited by a 25-Hz amplitude-modulated 4.5 MHz signal generated by a dual-channel waveform generator (33522A, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The −6 dB focal region has an ellipsoid shape with 1.35 mm in the axial direction and 0.25 mm in the lateral direction. A 64-element phased array transducer (P4-2, ATL., Bothell, WA USA) with a center frequency at 2.5 MHz was confocally aligned with the HIFU transducer to transmit and receive through a 4-board VDAS system (V-1, Verasonics, Bothell, WA, USA) at a sampling frequency of 10 MHz.

E. Focal spot localization technique

In this study, a short, continuous AM HIFU wave was used for localizing the focused ultrasound beam. A 1-s duration was sufficient to obtain stabilized HMI displacement while short enough to avoid significant temperature rise (Hou et al., 2010). In the 1D system, RF signals were directly acquired from the single-element transducer. While in the 2D system, graphical processing unit (GPU) was used to perform efficient beamforming (Li and Li, 2011; Chang et al., 2009; Hou et al., 2014c). The channel signals were acquired individually through the 64-channel phased array probe through VDAS system using a custom flash plane wave transmit imaging sequence. A GPU-based algorithm was used to beamform and upsample the RF signal to 80 MHz. The aperture width of the imaging probe is 1.9 cm and the lateral resolution is 0.3 mm in obtained 2D HMI images. The acquired element data to the RF signals (Hou et al., 2014c). The frame rate of both systems was 1000 frames/s. One-dimensional cross-correlation (Luo and Konofagou, 2010) of the consecutively acquired RF signals was applied on the acquired frames acquired at a frame rate of 1000 frames/s with a kernel size equal to 5 wavelengths of the imaging probe and 90% overlap to estimate incremental axial displacement as a result of oscillatory radiation force. Cross-correlation coefficient maps were also generated to determine the level of decorrelation noise, which is an indicator of the estimation accuracy. After low-pass filtering with a cutoff frequency at 100 Hz, the 50-Hz displacement was obtained, and a peak-to-peak displacement map could be generated across the axial direction. A maximum peak-to-peak displacement value was found across the axial direction. Based on the maximum peak-to-peak displacement value, we calculated −3 dB and −6 dB displacement focal zone over the axial direction. The results allowed for monitoring of tissue displacement profile across targeting depth during both focal spot localization and HIFU ablation. The peak-to-peak displacement profiles were estimated across all imaging depths for all specimens and were plotted against imaging depth.

In HMI, the acoustic radiation force can be described by (Nyborg, 1965; Palmeri et al., 2005)

| (1) |

where c is the speed of sound (1540 m/s in soft tissue), I(t) (W/cm2) is the intensity and α (dB/cm/MHz) is the absorption coefficient of the tissue. Assuming homogeneity within the specimen, the change in the radiation force F was thus only dependent on the intensity I(t). Subsequentially, higher HMI displacement D is indicative of higher radiation force which induced vibration. Therefore, the amplitude of peak-to-peak HMI displacement is directly correlated with acoustic intensity in a homogenous phantom or tissue. Based on this relationship, the −3 dB and −6 dB focal zones were computed based on the maximum peak-topeak displacement amplitude in the same trial. In in vitro liver experiments, a 2-min tissue ablation was performed to generate a lesion in the targeted area as in our previous studies (Hou et al., 2014a). Lesion locations were compared with the corresponding focal spot localization results.

To assess the capability of the method in the presence of aberration, an aberration layer (Krucker et al., 2002; Mirzania et al., 2015) was introduced between the HIFU transducer and the gel phantom. The aberration layer made of agar was placed above the gel phantom in order to create phase distortion within the incident HIFU beam. The incidence angle between the primary beam direction and the wedge shaped aberration layer is 11°.

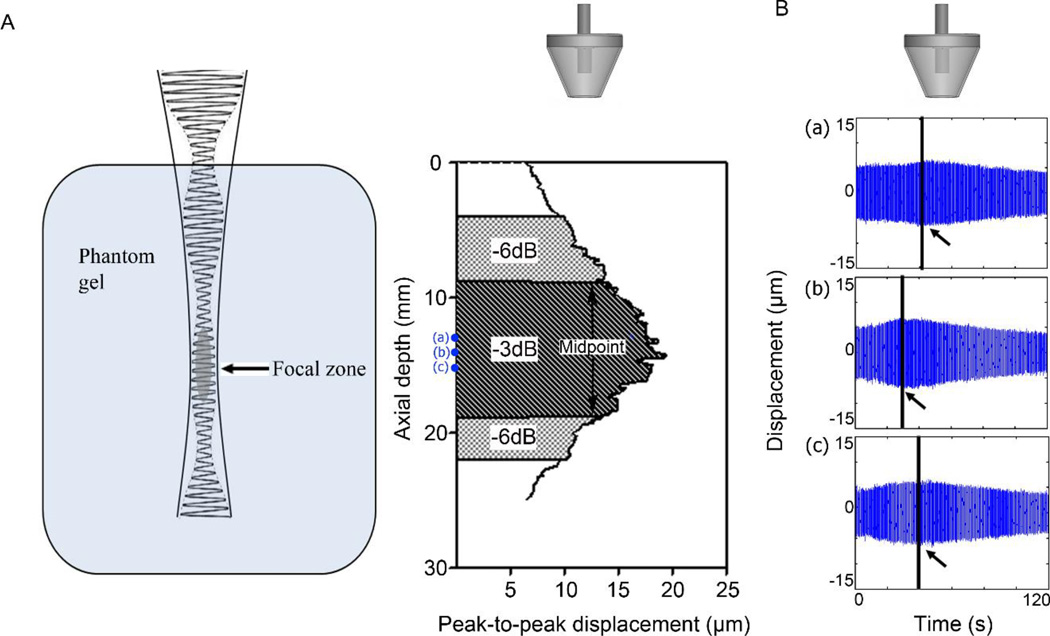

In order to assess the accuracy of the aforementioned focal spot localization method, it is idealistic to detect the apparent focal region by searching for the highest rate of temperature change as a comparison. However, the thermocouple was not used in this study in order to avoid imaging artifacts. Here, we propose an alternative approach to measure the apparent focal spot based on the relative change of monitoring displacement profiles during HIFU ablation across the imaging depth. That is, the location with earliest decrease in displacement is defined as the focal spot where the temperature rose fastest. From our previous work (Maleke and Konofagou, 2008), the peak-to-peak amplitude of the HMI focal displacement first increases then decreases as tissue undergoes initial softening followed by stiffening during slow thermal ablation, which is the pattern of stiffness change under slow denaturation (Figure 2B) (Hill and ter Haar, 1995). Assuming that the targeted in vitro liver tissue is homogeneous and the target region coagulates at the same temperature, then the time point at which the tissue starts to stiffen can indirectly indicate that the tissue has reached the temperature causing irreversible protein denaturation (Wu et al., 2001; Sapin-de Brosses et al., 2010). In order to successfully find the peak in this variation, an envelope detection algorithm was applied across the 2-min long monitoring displacement to detect the time-point at which the tissue started to undergo stiffening. The time to undergo stiffening was computed across all acquired depths. The depth with the shortest time to stiffening (TTS) was considered as the actual focal spot (AFS) since thermal dosage was delivered most at this depth.

Figure 2.

(A) Overview of the generation of oscillatory radiation force and an example of HMI peak-to-peak displacement recorded in vitro canine liver specimen. The −3 dB and −6 dB focal zone was computed based on the maximum peak-to-peak displacement amplitude. (B) HMI monitoring during 2-minute ablation at 3 depths (a), (b) and (c). The three different depths are marked in (A).

During ablation, the in situ acoustic intensity was equal to 4200 W/cm2 and the duration was equal to 120 s. Once a thermal lesion was generated, a post-ablative HMI was performed (Isptp = 4200 W/cm2, duration = 1s) to obtain the stiffness contrast map. The midpoint of the lesion in histology was measured to represent the location of the lesions. The midpoint of the −3 dB focal region was thus estimated to represent the focal spot localization method for comparison purposes.

Results

A. 1D HMI on phantoms

The intensity of the focused ultrasound beam was detectable by estimating the harmonic displacement in homogeneous gelatin phantoms. Figure 2.A depicts an example of 1D peakto- peak displacement profile along the axial direction in a gelatin phantom. The targeted region could be represented as the −3 dB focal zone. Figure 2.B shows the representative 2- min HMI displacement of 3 depths (a), (b) and (c) within the focal region. The displacement at all three depths initially increased then decreased as tissue underwent initial softening followed by stiffening during slow thermal ablation. The time point at which the tissue started to stiffen is marked with a black line and arrow. The time taken to reach this timepoint was computed as the time to stiffening (TTS).

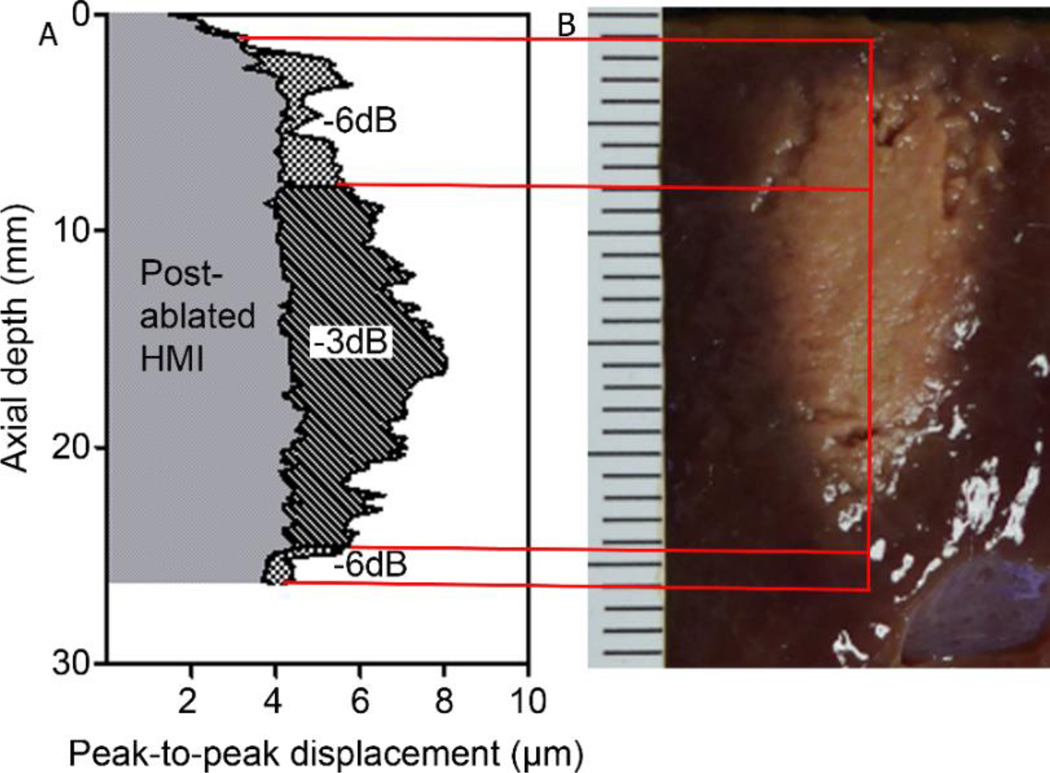

B. 1D HMI on in vitro liver specimens

An example of HMI displacement image of an in vitro canine liver specimen using the 1D system before and after ablation is shown in Figure 3. The −3 dB and −6 dB focal zone was estimated based on the 1-s HMI before ablation. A post-ablative HMI was recorded after 2- min ablation monitoring. The peak-to-peak displacement contrast was capable of delineating the lesion generated when compared against gross pathology. The midpoint of the lesion in pathology on the right panel was measured to represent the location of the lesion.

Figure 3.

1D HMI displacement image of an in vitro canine liver specimen before and after ablation. The −3 dB and −6 dB focal zone was estimated based on the maximum peak-to-peak displacement amplitude. A post-ablative HMI was recorded after 2 min ablation. The peak-to-peak displacement contrast could indicate the lesion generated when comparing with the transverse section in gross pathology on (B). The red lines are indicating the corresponding −3 dB and −6 dB regions in gross pathology.

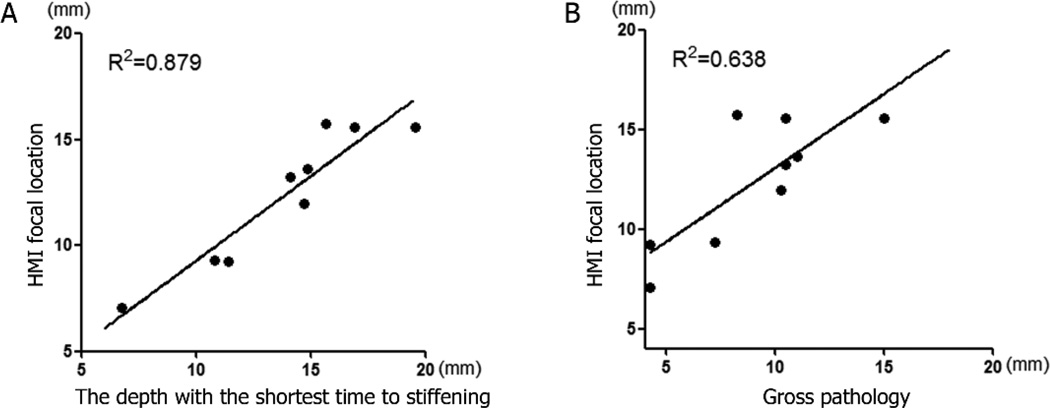

Linear regression was performed in nine thermal lesions in order to establish the relationship between the focal spot location identified with HMI and the shortest TTS location. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis equal to 0.879 and p<0.0002. The slope of the best-fit line is 0.930 ± 0.155 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.562 to 1.298. Another linear regression was performed on those lesions between the location of focal regions from focal spot localization and the location of true physical lesions from histology. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis is 0.638 and p<0.001 as shown in Figure 4. The slope of the linear regression fit is 0.743 ± 0.212 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.242 to 1.243.

Figure 4.

Verification of focal spot localization results. (A) Comparison between the midpoint of −3 dB focal zone computed from focal spot localization with the location of the corresponding shortest TTS points. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis is 0.879 for the 9 data points used in this study. The corresponding p value is <0.0002. (B) Comparison between the midpoint of −3 dB focal zone computed from focal spot localization with midpoint of lesion from gross pathology. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis is 0.638 for the 9 data points used in this study. The corresponding p value is <0.001.

C. 2D HMI on phantoms and in vitro liver specimens

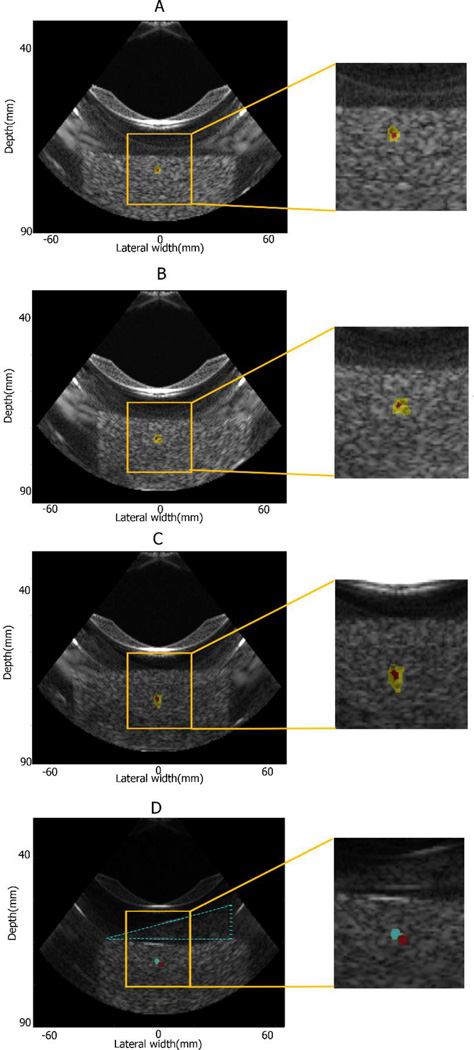

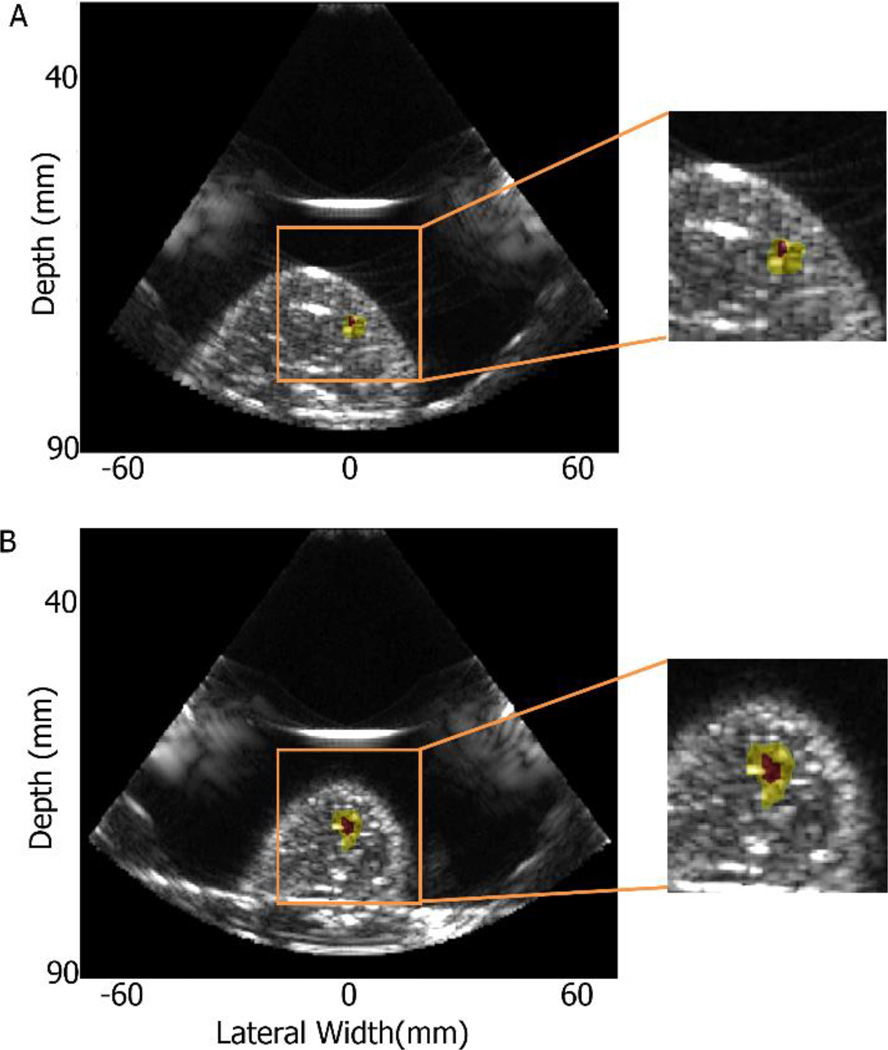

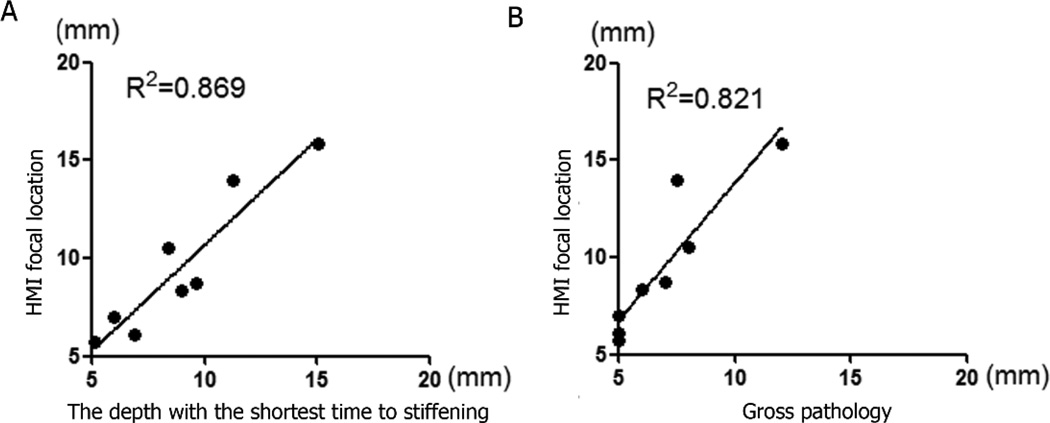

Figure 5(A)–(C) shows the estimated focal region using the HMI-based focal spot localization method overlaid onto the B-mode image of gelatin phantoms. The yellow region represents the −6 dB focal region, and the red region represents the −3 dB focal region. The transducer was moved across various lateral and axial locations within the phantom. In Figure 5 (D), the aberration layer is delineated by blue dash line. The red region represents the −3 dB focal region without the aberration layer, and the blue region represents the −3 dB focal region with the aberration layer. A shift of the focal spot due to aberration was detected. The axial movement of the focal spot was within the range of 66.3 to 69.8 and 65.9 mm to 69.7 mm in phantom and liver respectively. Figure 6 shows the estimated focal region using the HMI focal spot in in vitro liver specimens. In Figure 7, linear regression was performed in eight lesions in order to establish the relationship between the location of focal regions from focal spot localization and the location of the corresponding shortest TTS points. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis is 0.869 and p<0.001. The slope of the linear regression fit is 1.079 ± 0.171 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.661 to 1.498. Another linear regression was performed in those lesions between the location of the focal regions predicted by HMI and the true location of the lesions from histology. The R2 value is 0.821 at p<0.002. The slope the linear regression fit is 1.415 ± 0.269 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.756 to 2.074.

Figure 5.

Focal spot localization application on phantom in 2D HMI system. The focal region from focal spot localization method was overlaid to the B mode image in (A) (B) and (C): the yellow region represents the −6 dB focal region, and the red region represents the −3 dB focal region. In (D), the aberration layer is delineated with blue dash line. The red region represents the −3 dB focal region without the aberration layer, and the blue region represents the −3 dB focal region with the aberration layer.

Figure 6.

Focal spot localization application on in vitro liver in 2D HMI system. The focal region from focal spot localization method was overlaid on the B mode image: the yellow region represents the −6 dB focal region, and the red region represents the −3 dB focal region.

Figure 7.

Verification of focal spot localization results in 2D HMI system. (A) Comparison between the midpoint of −3 dB focal zone computed from focal spot localization with the location of the corresponding shortest TTS points. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis is 0.869 for the 8 data points used in this study. The corresponding p value is <0.001. (B) Comparison between the midpoint of −3 dB focal zone computed from focal spot localization with midpoint of lesion from gross pathology. The R2 value from the statistical regression analysis is 0.821for the 8 data points used in this study. The corresponding p value is <0.002.

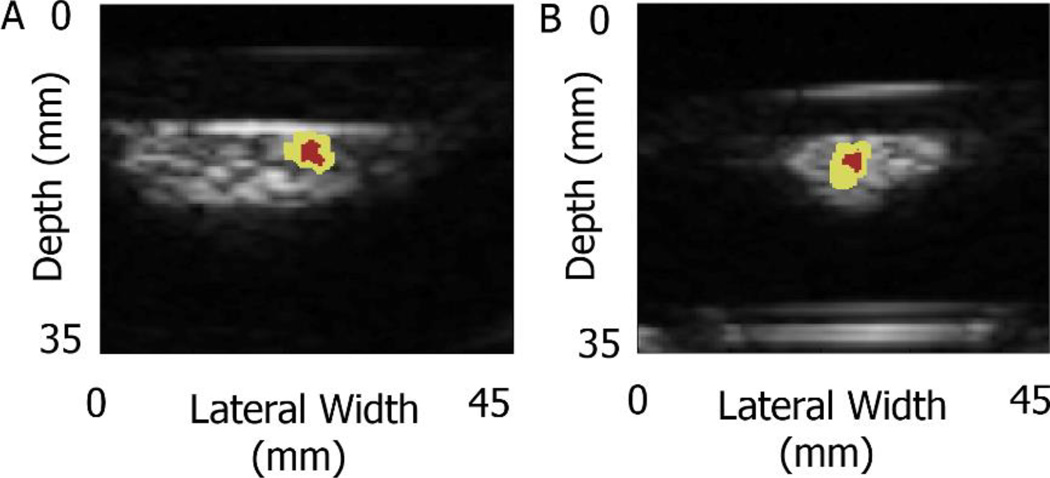

D. 2D HMI on ex vivo human breast tumor specimens

A representative application of the estimated focal region using the HMI focal spot in ex vivo human breast specimens is shown in Figure 8: (A) normal breast tissue and (B) IDC. The focal region from focal spot localization method was overlaid on the B mode image: the yellow region represents the −6 dB focal region, and the red region represents the −3 dB focal region.

Figure 8.

Focal spot localization application on ex vivo human breast tissue in 2D HMI system: (A) normal breast tissue and (B) IDC. The focal region from focal spot localization method was overlaid on the B mode image: the yellow region represents the −6dB focal region, and the red region represents the −3dB focal region.

Discussion

Several ultrasound-based imaging modalities have been proposed for image guidance and monitoring of HIFU surgery. However, accurate localization and characterization of the effective region of treatment in real-time remain as the obstacles in the clinical implementation of HIFU ablation. In this study, we investigated on an important challenge for focused ultrasound treatment planning, i.e. the visualization of the focal region prior to treatment. In this study, a focal spot localization method was developed with a radiation- force-based technique of HMI based on both 1D and 2D systems. The capability of HMI to simultaneously generate oscillatory radiation force and monitor the induced local displacement at the focus are considered unique advantages. Minimal interference between high power FUS and diagnostic beams is achieved by performing analog and digital filtering, thus phantom/tissue displacements can be accurately estimated using the filtered RF signals.

The method presented herein was also shown to be efficient requiring under 1s for data acquisition. Based on previous thermometry studies, a 1-s excitation under 25 Hz modulation frequency consisted of 50 oscillation cycles was used to reliably obtain steady-state HMI displacement while avoiding any significant temperature rise (Hou et al., 2014a). It is noteworthy that despite the speed of sound can vary with temperature, the offset caused by the speed of sound change could be filtered out as DC component from the oscillation in the focal spot localization process.

The midpoint of the −3 dB focal region was thus estimated to represent the focal spot. The midpoint of the −6 dB focal region was also considered. Because the −6 dB focal region is bigger than the −3 dB focal region, it introduces more noise in the estimation process. The midpoint of the −6 dB focal region therefore tends to be less accurate in terms of focal spot localization. We have shown that the region with the highest heating rate is also the region with the shortest time to stiffening. This was in agreement with its predicted focal spot by HMI in Figure 7.A. However, Figure 7.B shows a slight discrepancy between our method and gross pathology in the evaluation of the location of the lesion in this study. The lesions measured by gross pathology tend to be closer to the transducer by 2.59 mm than the locations estimated by HMI. The discrepancy can be due mainly to the heat diffusion of HIFU-induced lesions. It is known that the geometry of the lesion axial cross section may not be ideal ellipsoidal shape but a tadpole lesion with centroids displaced from the focus toward the transducer (Khokhlova et al., 2006; Watkin et al., 1996; Bailey et al., 2001). It is likely that the discrepancy between the gross pathology location and the HMI location is due to the tadpole-shaped lesions that have grown towards the transducer. This is consistent with the linear regression results in Figure 5.B where the axial midpoint of lesions tends to be closer to the tissue surface than the estimated focuses. A single expert was used for manual segmentation of the lesion. The manually segmented lesion on the pathology may have also introduced discrepancies. For the 2D HMI data, the axial and lateral resolutions were 0.087 mm and 0.3 mm respectively. In the lesion measurement, although the boundaries of the lesions have sharp contrast from the surrounding normal tissue, the physical measurement was on 0.1 mm scale.

Despite our successful implementation on both 1D and 2D HMI platforms, there are several limitations. One limitation of this study is the absence of temperature measurement during HIFU treatment. The placement of a thermocouple within the tumor typically generates additional heat accumulation due to the beam interference with the thermocouple. This would influence the associated displacement estimation. Hence, simultaneous temperature measurement was excluded in this study. However, a location with shortest TTS, which may suggest quickest coagulation, was considered as the focal spot in the axial direction. Furthermore, although off-line processing was used in this study, the 2D HMI system has the fundamental capability of on-line monitoring. Ongoing work explores the potential of using on-line HMI focal spot localization to provide feedback control with a display frame rate up to 15 Hz. Other ongoing and future work includes implementation for in vivo treatment of tumors in small animals.

Conclusion

A new HIFU treatment planning method was described that used oscillatory radiation force induced displacement amplitude variations to detect the HIFU focal spot before lesioning. This method was applied on tissue-mimicking phantoms and in vitro tissues with both the 1D and 2D HMI systems. Using this method, we were able to visualize the HMIFU focal region at variable depths. By comparing the estimated displacement profiles with lesion locations in pathology, we demonstrated the feasibility of using this HMI-based technique to localize the HIFU focal spot and predict lesion location during the planning phase. The same application feasibilities were also demonstrated in a 2D preclinical system. We concluded that HMI has the potential of providing the capability for HIFU planning.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant R01EB014496.

References

- Auboiroux V, Viallon M, Roland J, Hyacinthe JN, Petrusca L, Morel DR, Goget T, Terraz S, Gross P, Becker CD, Salomir R. ARFI-prepared MRgHIFU in liver: simultaneous mapping of ARFI-displacement and temperature elevation, using a fast GRE-EPI sequence. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;68:932–946. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MR, Couret LN, Sapozhnikov OA, Khokhlova VA, ter Haar G, Vaezy S, Shi X, Martin R, Crum LA. Use of overpressure to assess the role of bubbles in focused ultrasound lesion shape in vitro. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2001;27:695–708. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamber JC, Hill CR. Ultrasonic attenuation and propagation speed in mammalian tissues as a function of temperature. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 1979;5:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(79)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohris C, Schreiber WG, Jenne J, Simiantonakis I, Rastert R, Zabel HJ, Huber P, Bader R, Brix G. Quantitative MR temperature monitoring of high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging. 1999;17:603–610. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(98)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LW, Hsu KH, Li PC. Graphics Processing Unit-Based High-Frame-Rate Color Doppler Ultrasound Processing. Ieee T Ultrason Ferr. 2009;56:1856–1860. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung AH, Hynynen K, Colucci V, Oshio K, Cline HE, Jolesz FA. Optimization of spoiled gradient-echo phase imaging for in vivo localization of a focused ultrasound beam. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1996;36:745–752. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TJ, Bilgen M, Insana MF, Krouskop TA. Phantom materials for elastography. Ieee T Ultrason Ferr. 1997;44:1355–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Hill CR, ter Haar GR. Review article: high intensity focused ultrasound--potential for cancer treatment. The British journal of radiology. 1995;68:1296–1303. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-68-816-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou GY, Luo J, Marquet F, Maleke C, Vappou J, Konofagou EE. Performance assessment of HIFU lesion detection by harmonic motion imaging for focused ultrasound (HMIFU): a 3-D finite-element-based framework with experimental validation. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2011;37:2013–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou GY, Luo JW, Maleke C, Konofagou EE. Simulation of HMIFU (Harmonic Motion Imaging for Focused Ultrasound) with in-vitro validation. Northeast Bioengin C. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Hou GY, Marquet F, Wang S, Konofagou EE. Multi-parametric monitoring and assessment of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) boiling by harmonic motion imaging for focused ultrasound (HMIFU): an ex vivo feasibility study. Physics in medicine and biology. 2014a;59:1121–1145. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/5/1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou GY, Provost J, Grondin J, Wang ST, Marquet F, Bunting E, Konofagou EE. Sparse Matrix Beamforming and Image Reconstruction for 2-D HIFU Monitoring Using Harmonic Motion Imaging for Focused Ultrasound (HMIFU) With In Vitro Validation. Ieee T Med Imaging. 2014c;33:2107–2117. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2332184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illing RO, Kennedy JE, Wu F, ter Haar GR, Protheroe AS, Friend PJ, Gleeson FV, Cranston DW, Phillips RR, Middleton MR. The safety and feasibility of extracorporeal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for the treatment of liver and kidney tumours in a Western population. British journal of cancer. 2005;93:890–895. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye EA, Chen J, Pauly KB. Rapid MR-ARFI method for focal spot localization during focused ultrasound therapy. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;65:738–743. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JE, Wu F, ter Haar GR, Gleeson FV, Phillips RR, Middleton MR, Cranston D. High-intensity focused ultrasound for the treatment of liver tumours. Ultrasonics. 2004;42:931–935. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2004.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlova VA, Bailey MR, Reed JA, Cunitz BW, Kaczkowski PJ, Crum LA. Effects of nonlinear propagation, cavitation, and boiling in lesion formation by high intensity focused ultrasound in a gel phantom. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119:1834–1848. doi: 10.1121/1.2161440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konofagou EE, Hynynen K. Localized harmonic motion imaging: theory, simulations and experiments. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2003;29:1405–1413. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouskop TJHMBMFITA. Phantom Materials for Elastography. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ULTRASONICS. 1997;44 [Google Scholar]

- Krucker JF, LeCarpentier GL, Fowlkes JB, Carson PL. Rapid elastic image registration for 3-D ultrasound. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002;21:1384–1394. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.806424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YF, Li PC. Software Beamforming: Comparison between a Phased Array and Synthetic Transmit Aperture. Ultrasonic imaging. 2011;33:109–118. doi: 10.1177/016173461103300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Konofagou E. A fast normalized cross-correlation calculation method for motion estimation. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2010;57:1347–1357. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn JG, Zwemer RL, Chick AJ. The Biological Application of Focused Ultrasonic Waves. Science. 1942;96:119–120. doi: 10.1126/science.96.2483.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleke C, Konofagou EE. Harmonic motion imaging for focused ultrasound (HMIFU): a fully integrated technique for sonication and monitoring of thermal ablation in tissues. Physics in medicine and biology. 2008;53:1773–1793. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/6/018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleke C, Konofagou EE. In vivo feasibility of real-time monitoring of focused ultrasound surgery (FUS) using harmonic motion imaging (HMI) IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 2010;57:7–11. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2027423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Maier SE. Magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging. Medical physics. 2008;35:3748–3758. doi: 10.1118/1.2956712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzania R, Shapoori K, Malyarenko E, Maev RG. Ultrasonic imaging of static objects through an aberrating layer using harmonic phase conjugation approach. Ultrasonics. 2015;58:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell M, Flax SW. Phase aberration measurements in medical ultrasound: human studies. Ultrasonic imaging. 1988;10:1–11. doi: 10.1177/016173468801000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeri ML, Sharma AC, Bouchard RR, Nightingale RW, Nightingale KR. A finite-element method model of soft tissue response to impulsive acoustic radiation force. Ieee T Ultrason Ferr. 2005;52:1699–1712. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1561624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapin-de Brosses E, Gennisson JL, Pernot M, Fink M, Tanter M. Temperature dependence of the shear modulus of soft tissues assessed by ultrasound. Physics in medicine and biology. 2010;55:1701–1718. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/6/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal CM, Brown GM, Bahn RC, Greenleaf JF. Measurement and use of acoustic nonlinearity and sound speed to estimate composition of excised livers. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 1986;12:865–874. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip R, Ebbini ES. Noninvasive estimation of tissue temperature response to heating fields using diagnostic ultrasound. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 1995;42:828–839. doi: 10.1109/10.398644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Vanbaren P, Ebbini ES. Two-dimensional temperature estimation using diagnostic ultrasound. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 1998;45:1088–1099. doi: 10.1109/58.710592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaezy S, Shi X, Martin RW, Chi E, Nelson PI, Bailey MR, Crum LA. Real-time visualization of high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment using ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2001;27:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkin NA, ter Haar GR, Rivens I. The intensity dependence of the site of maximal energy deposition in focused ultrasound surgery. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 1996;22:483–491. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(95)02062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley LN. Acoustic streaming. In: Mason WP, editor. Physical Acoustics. New York: Academic Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Felmlee JP, Greenleaf JF, Riederer SJ, Ehman RL. Assessment of thermal tissue ablation with MR elastography. Magnet Reson Med. 2001;45:80–87. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200101)45:1<80::aid-mrm1012>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Vaezy S. A targeting method based on acoustic backscatter for treatment planning in tissue ablation using focused ultrasound. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 2010;57:71–79. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2026581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]