Abstract

This retrospective cohort study using electronic questionnaires compared the perioperative complication rates of tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO) surgery and the 8-week, 6-month, and 1-year functional outcomes, between rehabilitation and traditional post-operative management. Dogs were placed into 1 of 2 cohort groups based on attending veterinarian’s selected management: i) “traditional” involving restriction to cage rest and leash walking, and ii) “rehabilitation” performed by a certified practitioner. There was no statistically significant difference in complication rates in the perioperative period between the 2 treatment cohorts (P > 0.1). The rehabilitation group was 1.9 times more likely to reach full function at 8 wk (P = 0.045). Conversely, the traditional group was 2.9 times more likely be categorized as having unacceptable function at 8 wk after surgery (P = 0.05). This study suggests that rehabilitation performed by a certified practitioner is safe and may improve short-term outcomes when used in the initial postoperative management for dogs treated with TPLO.

Résumé

Sécurité et résultats fonctionnels associés à la thérapie de réadaptation à court terme dans la thérapie de la gestion postopératoire de l’ostéotomie de nivellement du plateau tibial. Cette étude rétrospective de cohortes à l’aide de questionnaires a comparé les taux des complications périopératoires de la chirurgie de l’ostéotomie de nivellement du plateau tibial (ONPT) et les résultats fonctionnels à 8 semaines, à 6 mois et à 1 an, entre la réadaptation et la gestion postopératoire traditionnelle. Les chiens ont été placés dans 1 de 2 groupes de cohorte selon la gestion choisie par le vétérinaire traitant : i) la «gestion traditionnelle» comportant le repos en cage et la marche en laisse et ii) la «réadaptation» effectuée par un praticien certifié. Il n’y avait pas de différence statistique significative pour les taux de complication durant la période périopératoire entre les 2 cohortes de traitement (P > 0,1). Il était 1,9 fois plus probable que le groupe de réadaptation parvienne à une fonction complète à 8 semaines (P = 0,045). Inversement, il était 2,9 fois plus probable que le groupe traditionnel soit classé comme ayant une fonction inacceptable à 8 semaines après la chirurgie (P = 0,05). Cette étude suggère que la réadaptation effectuée par un praticien certifié est sécuritaire et améliore les résultats à court terme lorsqu’elle est utilisée dans la gestion postopératoire des chiens traités à l’aide d’une ONPT.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Canine rehabilitation has been growing in awareness and application in the last decade with the establishment of training and certification centers such as the University of Tennessee (http://ccrp.utvetce.com/) and the Canine Rehabilitation Institute (http://www.caninerehabinstitute.com/), as well as the founding of the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation (http://vsmr.org/). As this area of veterinary medicine continues to expand, it is imperative that rehabilitation practices are based on scientific evidence for their safe and effective implementation. Therapeutic exercises and supplemental treatments administered during the first few months of post-operative recovery from orthopedic procedures are some of the most common applications for rehabilitation in current small animal practice. Based on the frequency of use and the potential for associated complications if done improperly, studies regarding the safety and efficacy associated with rehabilitation for this indication are critical.

There are currently 2 primary schools of thought regarding management of canine patients during the first few months of post-operative recovery from orthopedic procedures: firstly, the “traditional protocol” of cage rest and restriction of exercise including limited leash walks, and secondly, the rehabilitation protocols of movement and intervention (1). Practitioners’ oft-expressed rationale for the exclusion of rehabilitation protocols is concern over safety, as well as a perceived lack of necessity. The latter perception has begun to be studied in research which examines problems that can be addressed with rehabilitation as well as quantitative outcomes of post-operative rehabilitation (2–7). The former rationale has yet to be studied: a Pub Med (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) search using the combined search criteria “dog,” “canine,” “rehabilitation,” “physical therapy,” and “safety” did not yield any publications. The present study was designed to assess the safety of rehabilitation when performed by personnel trained and certified in veterinary rehabilitation; specifically, it is a retrospective, multi-center cohort study examining the safety of employing rehabilitation protocols during the post-operative period following tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) surgery of a single leg.

The null hypothesis of this study was that there is no difference in complication rates and functional outcome measures between dogs that have received post-operative rehabilitation performed by personnel trained and certified in veterinary rehabilitation and dogs that did not have dedicated rehabilitation after TPLO. The study objective was to survey veterinarians to gather data on complication rates and functional outcomes in dogs that had undergone a single TPLO surgery, with no other orthopedic or systemic diseases, and compare safety and efficacy data between post-operative rehabilitation and “traditional protocol” groups. Data regarding type of rehabilitation therapies employed and the subsequent incidence of cranial cruciate ligament disease in the contralateral hindlimb were also gathered.

Materials and methods

An electronic questionnaire was designed to collect data regarding complication rates and outcome measures following a canine unilateral TPLO surgery. This surgery was chosen because it is both pervasive and standardized (8). The survey was conducted for 3 mo on the Veterinary Information Network (www.VIN.com), and for 9 mo on a secondary established survey site (www.surveymonkey.com). The survey list was generated by the VIN e-mailing all its veterinary members, as well as through veterinary associations in Canada (provincially and locally), and veterinary companies that provided the Survey Monkey link to veterinarians. The survey was limited to veterinarians and gathered 12 separate pieces of information (Appendix 1).

Appendix 1.

Questionnaire questions

|

Questionnaires were disqualified for the following reasons: i) the presence of other orthopedic diseases; ii) the presence of systemic diseases; iii) surgeons having < 5 y of experience doing TPLO surgery; iv) the questionnaire was not answered properly; or v) the questionnaire could not be clearly placed into either cohort group (i.e., a surgeon with no training performing rehabilitation or owners undertaking a home exercise program), rendering the information unusable for the study.

The completed questionnaires were divided into 2 cohort groups: i) dogs that had received post-operative care from a certified rehabilitation practitioner (“rehabilitation”); ii) dogs that had not received post-operative care beyond exercise restriction and leash walking (“traditional”). The questionnaire did not attempt to ascertain the degree of owner compliance or the specific instructions to the owner. A certified rehabilitation practitioner may be a veterinarian, a physical therapist, an animal health technologist, or a physical therapy assistant.

The perioperative complication rates were compared between the rehabilitation and traditional groups using previously established criteria for catastrophic, major, minor, and no complications (Table 1). The functional outcome as reported by the veterinarian between each group was compared at perioperative (8 wk), short-term (6 mo), and mid-term (1 y) time frames using previously established criteria of full, acceptable, and unacceptable (Table 2).

Table 1.

Definitions of complications (9)

| Catastrophic | Complication or associated morbidity that causes permanent unacceptable function, is directly related to death, or is cause for euthanasia. |

| Major | Complication or associated morbidity that requires further surgical or medical treatment to resolve. |

| Minor | Complication or associated morbidity not requiring additional surgical or medical treatment to resolve (e.g., bruising, seroma, minor incision problems, etc.). |

| No complications | Patient experienced no complications. |

Table 2.

Definitions of functional outcomes (9)

| Full | Restoration to, or maintenance of, full intended level and duration of activities and performance from preinjury or predisease status (without medication). |

| Acceptable | Restoration to, or maintenance of, intended activities and performance from preinjury or predisease status that is limited in level or duration and/or requires medication to achieve. |

| Unacceptable | All other outcomes. |

The perioperative complication rates and functional outcome results were evaluated using Chi-square analysis with odds ratio then calculated for the statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences. Fisher’s exact test was used for the complication rates and functional outcome measures of the short and mid-term time frames. The data concerning the prevalence of contralateral cruciate disease were analyzed using Chi-square analysis.

Results

Questionnaires

There were 358 questionnaires completed and returned. Of those, 236 questionnaires (66%) qualified for inclusion. The final data focused on unilateral TPLO surgeries with no known complications, performed by 189 board-certified surgeons and 47 general practitioners with > 5 y of experience performing TPLO surgery. Of the 236 questionnaires returned, 101 surgeries (43%) were followed up with rehabilitation performed by certified practitioners (“rehabilitation” group), and 135 cases (57%) were instructed to restrict exercise to leash walking (“traditional” group).

Cohort groups

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of years performing TPLO surgery between surgeons in the rehabilitation and traditional groups (P = 0.99). Differences regarding inclusion and type of joint exploration, findings, and treatment of CCL and meniscus were not requested or recorded for the experimental design. These data were beyond the scope of the study and considered unnecessary for testing the hypothesis. The study was intended to cover the spectrum of standard of care clinical practice, which was likely for both cohorts based on experimental design and study population. However, it is possible that there were differences in these variables between cohorts that could have influenced outcomes. There was no statistically significant difference in breed representation (P = 0.65) weight (P = 0.9), age (P = 0.99), or gender (P = 0.2) between the rehabilitation and traditional groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of signalment between rehabilitation and traditional groups

| Age (y) | 1 to 3 | 3 to 7 | >7 | |||||

| 22% | 19% | 59% | 62% | 19% | 19% | |||

| Gender | Female spayed | Male neutered | Female | Male | ||||

| 42% | 35% | 38% | 60% | 6% | 3% | 5% | 2% | |

| Weight (kg) | < 10 | 10 to 30 | 30 to 50 | > 50 | ||||

| 3% | 1% | 38% | 34% | 54% | 58% | 5% | 7% | |

| Breed | Labrador* | Golden retriever* | Rottweiler* | Other | ||||

| *3 most common | 41% | 37% | 9% | 8% | 12% | 5% | 38% | 50% |

Complication rate

The overall perioperative complication rate for both groups was 26.1%, which is consistent with other reported complication rates (10,11). The overall perioperative complication rate for dogs receiving rehabilitation was 25% and for the traditional group was 27.1%. The distribution of the types of complications is presented in Table 4. Specifically, there was no statistically significant difference between the rehabilitation and traditional groups for complications classified as catastrophic (P = 0.11, power 0.4), major (P = 0.11, power 0.3), minor (P = 0.65, power 0.7), or no complications (P = 0.69, power 0.8).

Table 4.

Types and percentages of perioperative complications

| Rehabilitation group | Traditional group | |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent lameness | 20% | 15% |

| Infection | 33% | 35% |

| Meniscal tear | 7% | 15% |

| Patellar desmitis | 13% | 12% |

| Seroma | 13% | 12% |

| Bleeding/bruising | 0% | 8% |

| Other | 13% | 4% |

Functional outcome

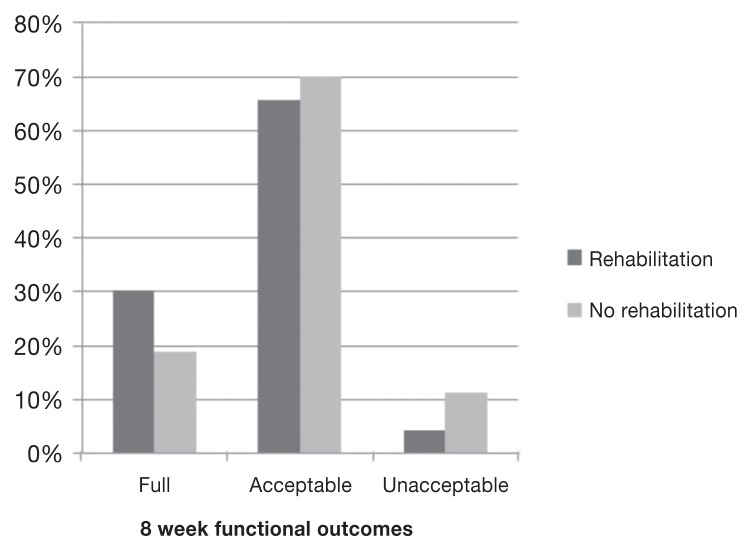

At 8 wk, dogs that received rehabilitation were reported to have an outcome measure 1.9 times more likely to return to full function (P = 0.045) based on questionnaire responses. Conversely, dogs in the traditional group were 2.9 times more likely to result in unacceptable function (P = 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for acceptable function (P = 0.49, power 0.8) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Eight-week functional outcomes for the rehabilitation and traditional treatment groups.

There was no statistically significant difference between the rehabilitation and traditional groups when comparing functional outcome at 6 mo (P = 0.22, power 0.5) and 1 y (P = 0.5, power 0.5).

There was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.89) between future contralateral cruciate disease and whether or not the dog received rehabilitation. However, over 50% of the included questionnaires did not contain any data regarding the contralateral leg.

Rehabilitation therapies utilized

The questionnaires revealed that, on average, 4.6 types of therapy were used on each individual dog. Table 5 outlines the rehabilitation therapies employed, and the percentage of usage for each.

Table 5.

Rehabilitation therapies and percentage of usage

| Therapy | Percent of usage |

|---|---|

| Underwater treadmill | 93% |

| Passive range of motion | 89% |

| Therapeutic exercises | 85% |

| Cryotherapy | 51% |

| Laser therapy | 94% |

| Therapeutic ultrasound | 3% |

| Electrical stimulation | 10% |

| Acupuncture | 15% |

| Chiropractic therapy | 9% |

| Pulsed signal therapy | 5% |

| Other | 4% |

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety of post-operative rehabilitation performed by trained practitioners for dogs undergoing unilateral TPLO compared with current standard of care “traditional” post-operative management. The data suggest that rehabilitation therapies performed by certified practitioners are safe, given that the perioperative complication rates between the 2 groups were not significantly different. The increase in return to full function and decrease in unacceptable function also underscore the necessity of rehabilitation post operatively. This conclusion mirrors studies in humans where the addition of rehabilitation has been found to be safe and to increase functional outcome (12,13).

A weakness in the study design was the retrospective nature of the questionnaire, which raises the possibility of recall bias. However, this appears to be of less concern given the overall complication rates were similar to previously reported complication rates, and not statistically different between the 2 groups. This type of study was chosen because it could immediately address safety concerns, as well as serve as a starting point for future studies. The questionnaire would have benefitted from a larger sampling period in order to increase the number of respondents, but the sampling period was terminated because ongoing requests for participants ceased to yield further completed questionnaires. A questionnaire study also raises the possibility that a personal motivation, such as wanting a positive or negative outcome to the study, could come into play. Finally, there is the possibility of respondents not fully understanding the questions, which was demonstrated when some of the completed questionnaires had to be excluded because they were not answered properly, for example, providing data on multiple animals when individual responses were required.

Veterinary rehabilitation training at the Canine Rehabilitation Institute and the University of Tennessee allows veterinarians, physical therapists, animal health technologists, and physical therapy assistants to be admitted. The efficacy of rehabilitation performed by each of these subset groups would be subject to a future study. There is the potential for differences in complications and outcomes between these subset groups, but this survey was not designed to probe these potential differences.

The only complication rate group that had a desired power was the no complications group. This could mean that either there is no difference in complication rates between the rehabilitation and traditional groups, suggesting that complication rates are not affected by post-operative rehabilitation, or that more respondents are needed to refine the data sufficient to establish a difference, if one exists.

It is encouraging to see that rehabilitation appears to return patients to full function sooner, and mitigates unacceptable outcomes. However, this could be misleading since the traditional group may be restricted from engaging in the activities that would otherwise allow them to be classified as full function, despite the dogs being capable of those activities. However, this restriction of activity does not explain the increase in the 8 wk unacceptable outcomes in the traditional group.

The data on contralateral cruciate disease may be misleading in that the maximal assessment for dogs in the present study was at 1 y, many dogs in this study did not have long-term data reported, and signalment factors were not analyzed (14).

This study does not provide information as to which rehabilitation therapies are most beneficial during the TPLO postoperative period, nor does it address the efficacy of owners conducting a home exercise program when not under the supervision of a certified practitioner. This study is also not designed to determine the efficacy of specific protocols; rather, it is a global evaluation of the potential harm, if any, when utilizing rehabilitation.

In order to properly evaluate the efficacy of specific rehabilitation protocols, a prospective cohort study with established rehabilitation protocols, as well as more quantitative data such as Force Plate Analysis, Gait Analysis Mats, Stifle Function Scores, Visual Analog Scores, Muscle Mass and Goniometry, would be warranted. In this study, on average, each rehabilitated patient received 4.6 different types of therapy, which can be regarded as a substantive rehabilitation protocol for each dog. Future studies could seek to isolate each therapy, as well as definite timing and intensity, in order to establish whether a specific therapeutic protocol had a positive, neutral, or detrimental effect on outcome, thereby establishing which therapeutic protocol is the most efficacious for post TPLO surgeries.

This study suggests that canine patients benefit from receiving rehabilitation therapy after surgery compared with the traditional post-operative protocols of cage rest and restriction of exercise. This study also suggests that rehabilitation is not only efficacious, but is also safe.

More studies of this nature will hopefully result in the incorporation of rehabilitation into practitioners’ post-operative protocols, leading to a wider acceptance of, and greater confidence in its benefits.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jeff Pearce, Dr. Mark Rishniw (Veterinary Information Network), and Darrell Ogden for their information technology and editorial help. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Slatter D. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. 2nd ed. Toronto, Ontario: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 1846. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drygas KA, McClure SR, Goring RL, Pozzi A, Robertson SA, Wang C. Effects of cold compression therapy on postoperative pain, swelling, range of motion, and lameness after tibial plateau leveling osteotomy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;238:1284–1291. doi: 10.2460/javma.238.10.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jandi AS, Schulman AJ. Incidence of motion loss of the stifle joint in dogs with naturally occurring cranial cruciate ligament rupture surgically treated with tibial plateau leveling osteotomy: Longitudinal clinical study of 412 cases. Vet Surg. 2007;36:114–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2006.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsolais GS, Dvorak G, Conzemius MG. Effects of postoperative rehabilitation on limb function after cranial cruciate ligament repair in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220:1325–1330. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.220.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monk ML, Preston CA, McGowan CM. Effects of early intensive postoperative physiotherapy on limb function after tibial plateau leveling osteotomy in dogs with deficiency of the cranial cruciate ligament. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:529–536. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.67.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shumway R. Rehabilitation in the first 48 hours after surgery. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2007;22:166–170. doi: 10.1053/j.ctsap.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moeller EM, Allen DA, Wilson ER, Lineberger JA, Lehenbauer T. Long-term outcomes of thigh circumference, stifle range-of-motion, and lameness after unilateral tibial plateau levelling osteotomy. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2010;23:37–42. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-09-04-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slocum B, Slocum TD. Tibial plateau leveling osteotomy for repair of cranial cruciate ligament rupture in the canine. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1993;23:777–795. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(93)50082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook JL, Evans R, Conzemius MG, et al. Proposed definitions and criteria for reporting time frame, outcome, and complications for clinical orthopedic studies in veterinary medicine. Vet Surg. 2010;39:905–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2010.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergh MS, Peirone B. Complications of tibial plateau levelling osteotomy in dogs. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2012;25:349–358. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-11-09-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christopher SA, Beetem J, Cook JL. Comparison of long-term outcomes associated with three surgical techniques for treatment of cranial cruciate ligament disease in dogs. Vet Surg. 2013;42:329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2013.12001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant JA. Updating recommendations for rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction: A review. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:501–502. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw T, Williams MT, Chipchase LS. Do early quadriceps exercises affect the outcome of ACL reconstruction? A randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grierson J, Asher L, Grainger K. An investigation into risk factors for bilateral canine cruciate ligament rupture. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2011;24:192–196. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-10-03-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]