Abstract

Background

Geriatric patients with femoral neck fracture (FNF) have unacceptably high rates of postoperative complications and mortality. The purpose of this study was to compare the effects of epidural anesthesia versus peripheral nerve block (PNB) on postoperative outcomes in elderly Chinese patients with FNF.

Methods

This retrospective study explored mortality and postoperative complications in geriatric patients with FNF who underwent epidural anesthesia or PNB at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital from January 2008 to December 2012. The electronic database at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital includes discharge records for all patients treated in the hospital. Information on patient demographics, preoperative comorbidity, postoperative complications, type of anesthesia used, and in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality after surgery was obtained from this database.

Results

Two hundred and fifty-eight patients were identified for analysis. The mean patient age was 79.7 years, and 71.7% of the patients were women. In-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year postoperative mortality was 4.3%, 12.4%, and 22.9%, respectively, and no differences in mortality or cardiovascular complications were found between patients who received epidural anesthesia and those who received PNB. More patients with dementia or delirium were given PNB. No statistically significant differences were found between groups for other comorbidities or intraoperative parameters. The most common complications were acute cardiovascular events (23.6%), electrolyte disturbances (20.9%), and hypoxemia (18.2%). Patients who received PNB had more postoperative delirium (P=0.027). Postoperative acute respiratory events were more common (P=0.048) and postoperative stroke was less common (P=0.018) in the PNB group. There were fewer admissions to intensive care (P=0.024) in the epidural anesthesia group. Key factors with a negative influence on mortality were acute cardiovascular events, dementia, male sex, age, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, acute respiratory events, intensive care admission, and comorbidities.

Conclusion

PNB was not associated with lower mortality or lower cardiovascular complication rates when compared with epidural anesthesia in elderly patients with FNF.

Keywords: femoral neck fractures, elderly, epidural anesthesia, peripheral nerve block, postoperative outcomes

Introduction

Femoral neck fractures (FNFs) are common injuries in geriatric patients, who are usually frail and very elderly, with more than 30% being 85 years of age or older.1,2 Furthermore, it is well known that these injuries are accompanied by high mortality rates, ranging from 11% to 36% within the 1st year after surgery,3,4 so swift and conclusive recommendations are needed to address this public health problem.5

Currently, three surgical treatment options are available for management of FNF, ie, internal fixation, hemiarthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The type of surgery offered is determined by the degree of fracture, the patient’s age, functional demands, and the risk profile, such as physical fitness and cognitive function.6,7

The choice of anesthesia for this type of surgery is still a matter of ongoing debate. Regional anesthesia including epidural anesthesia, peripheral nerve block (PNB), and general anesthesia are all suitable for surgery in frail patients. The first paper addressing type of anesthesia in these patients was published in 1936 by Nygaard. Since then, there have been many trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews on this subject.8–10 However, few papers have compared the postoperative outcomes of epidural anesthesia and PNB in older patients.11,12

A heterogeneous mix of fracture types, surgery, and anesthesia styles can affect the prognosis of these aged patients. Therefore, we decided to investigate a population with a more homogeneous fracture pattern, ie, FNF, and a homogeneous surgery type, ie, hemiarthroplasty, at our hospital to compare the effects of epidural anesthesia and PNB. The primary outcome was in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality after surgery. The secondary outcomes were postoperative complications. This retrospective study offered unique strength focusing on investigation of anesthetic factors influencing mortality and postoperative complications of elderly patients with FNF.

Materials and methods

Data source

This single-center retrospective study was conducted to explore mortality and postoperative complications in elderly patients undergoing urgent hemiarthroplasty for FNF under epidural anesthesia or PNB at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital from January 2008 to December 2012. Ethical consent was obtained from the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. The data were anonymized before analysis. Informed consent was waived. The electronic database at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital includes discharge records for all patients treated in the hospital. Information on patient demographics, preoperative comorbidities, postoperative complications, and type of anesthesia were retrieved from the database by MG and GW. In-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year postoperative mortality rates were recorded in a telephone interview by JJ.

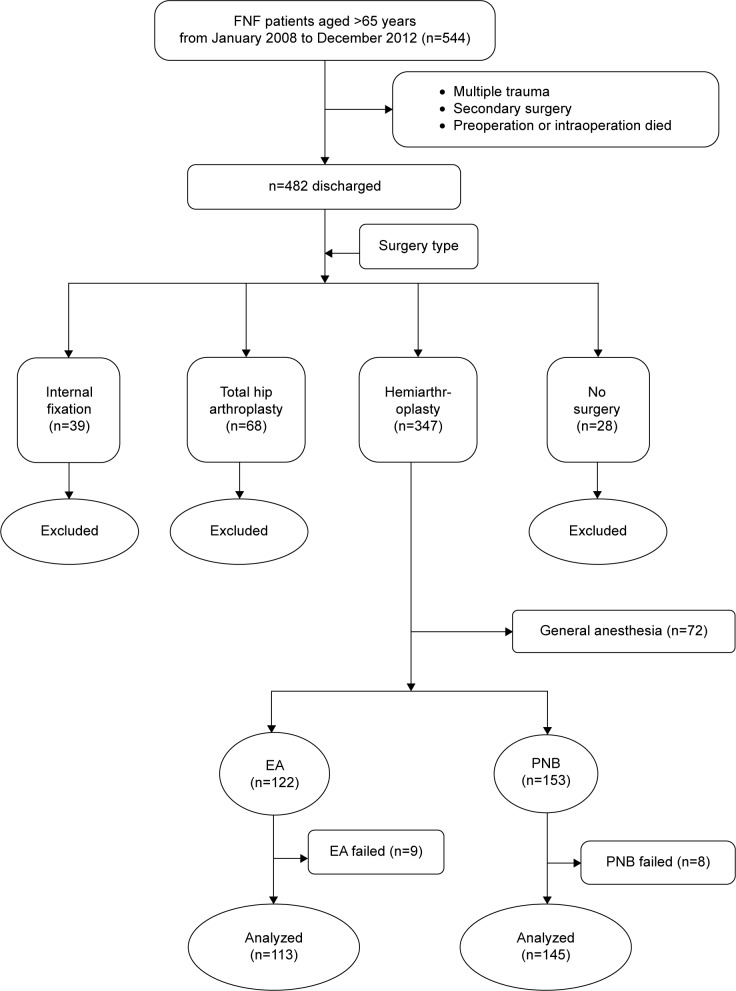

To create a cohort of patients aged 65 years or older, we identified all discharges with a principal or secondary diagnosis of FNF, including pathological fractures and trauma. To restrict our sample, we excluded patients diagnosed with multiple trauma, those who underwent a secondary surgical procedure during their hospital stay, those for whom a different type of surgery was performed, ie, internal fixation or total hip arthroplasty, and those who had no surgery. Of note, patients with failed epidural anesthesia or PNB who were subsequently converted to general anesthesia were also excluded from the analysis. Records for the remaining 258 subjects who received hemiarthroplasty were analyzed further (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing patient enrolment and analysis.

Abbreviations: EA, epidural anesthesia; PNB, peripheral nerve block; FNF, femoral neck fracture.

First, we evaluated in-hospital mortality because the immediate postoperative period is more likely to reflect anesthesia-related complications. Thirty-day mortality was included in the primary outcome because it is not subject to detection bias and because 30 days following surgery is the standard time point for assessing perioperative outcome. One-year mortality is usually considered as important observation time.

All patients were given low molecular weight heparin calcium (Fraxiparine®, GlaxoSmithKline) preoperatively and for at least 10 days postoperatively, interrupted only for the 24 hours before surgery to 12 hours after surgery. Ceftriaxone sodium (Rocephin®, Roche) 1.0 g was given 30 minutes preoperatively followed by two additional doses during the first 72 hours postoperatively.

Statistical analysis

The primary study outcome was in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality after surgery. The second outcomes were postoperative complications. General complications included the following: acute cardiovascular events, acute respiratory events, stroke, delirium, renal disease, electrolyte disturbances, anemia, hypoxemia, deep wound infection, and deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism. We also collected data on waiting time to operation, duration of surgery, length of postoperative hospital stay, admission to intensive care, hospital costs, blood loss, and transfusion.

For continuous parameters, Student’s t-tests are used to test for differences between groups, and for discontinuous parameters, chi-square statistics are used to detect differences between groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of all variables was used for 30-day and 1-year mortality after surgery. The significance level was set at 5% (P<0.05) for all statistical tests. Data were coded and stored in Microsoft Excel 2007 and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Demographics

Over the 5-year study period, 258 elderly patients of mean age 79.7 (range 65–109) years underwent hemiarthroplasty and were included for our analysis. The Student’s t-test or chi-square test was used to compare patient characteristics between the epidural anesthesia group and the PNB group (Table 1). Women (n=185, 71.7%) outnumbered their male counterparts. Waiting time to surgery, length of postoperative hospital stay, admission to intensive care, hospital costs, duration of surgery, intraoperative fluids required, blood loss, and transfusion in each of the two groups are presented in Table 2. No statistically significant differences were found, except for admission to intensive care, which was more common in the PNB group (χ2=5.695; P=0.024). Moreover, patients admitted to intensive care incurred more hospital costs, and their postoperative hospital stay was longer. Blood loss in the epidural anesthesia group was less than in the PNB group (382±170 mL versus 422±194 mL, respectively), but the difference was not statistically significant (95% CI (−5.47, −85.60); P=0.084). There were no significant differences in waiting time to operation, length of postoperative hospital stay, hospital costs, duration of surgery, intraoperative fluids required, and blood transfusion between the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics for 258 elderly patients receiving epidural anesthesia or PNB

| Total (n=258) | EA group (n=113) | PNB group (n=145) | χ2 | P-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex* | 73 (28.3%) | 28 (24.8%) | 45 (31.0%) | 1.225 | 0.330 | |

| Age (years)† | 79.7±6.8 | 78.8±6.5 | 80.1±7.0 | 0.129 | −2.980, −0.385 | |

| Weight (kg)† | 58.8±11.7 | 58.9±10.9 | 58.8±12.3 | 0.921 | −3.032, −2.741 | |

| Height (cm)† | 161.9±7.5 | 161.4±7.3 | 162.2±7.7 | 0.399 | −1.065, −2.665 | |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 22.27±3.54 | 22.57±3.65 | 22.22±3.75 | 0.448 | −1.269, −0.563 | |

| Surgical site (left)* | 133 (51.6%) | 61 (54.0%) | 72 (49.7%) | 0.476 | 0.490 | |

| ASA status* | 1.557 | 0.459 | ||||

| II | 97 (37.6%) | 45 (39.8%) | 52 (35.9%) | |||

| III | 116 (45.0%) | 52 (46.0%) | 64 (44.1%) | |||

| ≥IV | 45 (17.4%) | 16 (14.2%) | 29 (20.0%) |

Notes: Data are presented as the number (percentage), ratio, or mean ± standard deviation.

Chi-square test;

two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; EA, epidural anesthesia; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; PNB, peripheral nerve block.

Table 2.

Intraoperative and postoperative data for 258 elderly patients receiving epidural anesthesia or PNB

| Total (n=258) | EA group (n=113) | PNB group (n=145) | χ2 | P-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting time to operation (days)† | 7.04±3.98 | 6.76±3.81 | 7.26±4.11 | 0.317 | −0.482, −1.484 | |

| Postoperative LOS (days)† | 9.55±9.45 | 9.95±10.55 | 9.25±8.53 | 0.557 | −3.038, −1.641 | |

| ICU admission* | 49 (14.8%) | 11 (9.7%) | 29 (20%) | 5.109 | 0.024 | |

| Costs (103 RMB)† | 26.9±23.6 | 24.4±20.4 | 28.8±25.7 | 0.137 | −0.141, −1.022 | |

| Duration of surgery (minutes)† | 103±30 | 100±27 | 104±33 | 0.275 | −3.332, −11.649 | |

| Intraoperative fluids (mL)† | 708±198 | 691±190 | 723±200 | 0.192 | −16.23, −80.48 | |

| Blood loss (mL)† | 404±185 | 382±170 | 422±194 | 0.084 | −5.474, −85.60 | |

| Intraoperatively | 240±135 | 227±127 | 250±140 | 0.169 | −9.927, −56.496 | |

| Postoperatively | 164±111 | 155±103 | 172±118 | 0.231 | −10.719, −44.276 | |

| Blood transfusion (SAGM)† | ||||||

| Blood plasma | 247±257 | 228±298 | 260±222 | 0.319 | −31.376, −95.86 | |

| Red blood cells | 4.05±2.90 | 4.19±3.21 | 3.94±2.64 | 0.501 | −0.963, −0.472 | |

Notes: Data are presented as number (percentage), or ratio or mean ± standard deviation.

Chi-square;

two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EA, epidural anesthesia; PNB, peripheral nerve block; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; SAGM, modified saline-adenine-glucose.

Mortality

In-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality was 4.3%, 12.4%, and 22.9%, respectively. In-hospital mortality was slightly lower at 5.5% (8/145) in the PNB group when compared with 2.7% (3/113) in the epidural anesthesia group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.413, Fisher’s Exact test). One-year mortality was 24.1% (35/145) in the PNB group and 21.2% (24/113) in the epidural anesthesia group (χ2=0.30; P=0.582).

Preoperative comorbidities

Seventy-two patients (27.9%) in our study had no preoperative comorbidity, while 84 (32.6%) had one, 61 (23.6%) had two, and 41 (15.9%) had three or more comorbidities. Table 3 lists the comorbidities recorded and their incidence in the two groups. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular disease (78, 30.2%; One patient had a myocardial infarction after admission in each group), diabetes (60, 23.3%), respiratory disease (60, 23.3%), and stroke (56, 21.7%); one patient suffered a stroke after admission in each group. Dementia was more common in the PNB group than in the epidural anesthesia group (χ2=5.11; P=0.025). The proportion of patients with preoperative delirium was high in this frail patient group, being ten (8.8%) in the epidural anesthesia group and 23 (15.9%) in the PNB group (χ2=4.198; P=0.041). There were no statistically significant differences in other preoperative parameters between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Preoperative comorbidity, postoperative complications and mortality of 258 elderly patients in EA and PNB groups

| Total (n=258) | EA group (n=113) | PNB group (n=145) | χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative comorbidities | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 78 (30.2%) | 30 (26.5%) | 48 (33.1%) | 1.294 | 0.255 |

| Myocardial infarction | 23 (8.9%) | 9 (8.0%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.224 | 0.636 |

| Respiratory disease | 60 (23.3%) | 23 (20.4%) | 37 (25.5%) | 0.949 | 0.330 |

| Diabetes | 60 (23.3%) | 25 (22.1%) | 35 (24.1%) | 0.144 | 0.704 |

| Stroke | 56 (21.7%) | 24 (21.2%) | 32 (22.1%) | 0.026 | 0.873 |

| Dementia | 17 (6.6%) | 3 (2.7%) | 14 (9.7%) | 5.056 | 0.025 |

| Delirium | 33 (12.8%) | 10 (8.8%) | 23 (15.9%) | 4.198 | 0.041 |

| Renal disease | 28 (10.8%) | 14 (12.4%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.491 | 0.484 |

| Electrolyte disturbances | 24 (9.3%) | 10 (8.8%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.049 | 0.825 |

| Hypoxemia | 38 (14.7%) | 18 (15.9%) | 20 (13.8%) | 0.231 | 0.631 |

| Malignancy | 30 (11.6%) | 11 (9.7%) | 19 (13.1%) | 0.701 | 0.402 |

| Comorbidities (n) | 72 (27.9%) | 32 (28.3%) | 40 (27.6%) | 6.181 | 0.103 |

| 1 | 84 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 47 (32.4%) | ||

| 2 | 61 (23.6%) | 25 (22.1%) | 36 (24.8%) | ||

| ≥3 | 41 (15.9%) | 19 (16.8%) | 22 (15.2%) | ||

| Postoperative complications | |||||

| Acute cardiovascular events | 61 (23.6%) | 24 (21.2%) | 37 (25.5%) | 0.644 | 0.422 |

| Myocardial infarction | 9 (3.5%) | 3 (2.7%) | 6 (4.1%) | 0.415 | 0.520 |

| Acute respiratory events | 27 (10.5%) | 7 (6.2%) | 20 (13.8%) | 3.913 | 0.048 |

| Stroke | 20 (7.8%) | 11 (9.7%) | 4 (2.8%) | 5.644 | 0.018 |

| Delirium | 45 (17.4%) | 13 (11.5%) | 32 (22.1%) | 4.922 | 0.027 |

| DVT/PE | 12 (4.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 6 (4.1%) | 0.197 | 0.658 |

| Renal disorder | 46 (17.8%) | 20 (17.7%) | 26 (17.9%) | 0.002 | 0.962 |

| Electrolyte disturbances | 54 (20.9%) | 23 (20.4%) | 31 (21.4%) | 0.040 | 0.841 |

| Anemia | 38 (14.7%) | 17 (15.0%) | 21 (14.5%) | 0.016 | 0.900 |

| Hypoxemia | 47 (18.2%) | 24 (21.2%) | 23 (15.9%) | 1.232 | 0.267 |

| Deep wound infection | 25 (9.7%) | 12 (10.6%) | 13 (9.0%) | 0.199 | 0.656 |

| Complications (n) | 97 (37.6%) | 43 (38.1%) | 54 (37.2%) | 0.239 | 0.971 |

| 1 | 77 (29.8%) | 32 (28.3%) | 45 (31.0%) | ||

| 2 | 62 (24.0%) | 28 (24.8%) | 34 (23.5%) | ||

| ≥3 | 22 (8.5%) | 10 (8.8%) | 12 (8.3%) | ||

| Postoperative mortality | |||||

| In-hospital | 11 (4.3%) | 3 (2.7%) | 8 (5.5%) | 0.6699 | 0.4131 |

| 30-day | 32 (12.4%) | 12 (10.6%) | 20 (13.8%) | 0.5887 | 0.4429 |

| 1-year | 59 (22.9%) | 24 (21.2%) | 35 (24.1%) | 0.3026 | 0.5823 |

Notes: Data are presented as number (percentage), ratio, or mean ± standard deviation. Cardiovascular disease includes hypertension, coronary artery disease, and arrhythmia; respiratory disease includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonia, and chronic bronchitis. Differences in complication rates between the two groups were tested using chi-square statistics.

Abbreviations: EA, epidural anesthesia; PNB, peripheral nerve block; DVT/PE, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolus.

Postoperative complications

Seventy-seven patients (29.8%) have one postoperative complication, 62 (24.0%) had two complications, and 22 (8.5%) had three or more complications. Table 3 shows the incidence of postoperative complications, the most common of which were acute cardiovascular events (61, 23.6%), electrolyte disturbances (54, 20.9%), and hypoxemia (47, 18.2%). The incidence of acute respiratory events was higher in the PNB group (χ2=3.91; P=0.048), whereas postoperative stroke was significantly more common in the epidural anesthesia group (χ2=5.64; P=0.018). Six patients (5.3%) in the epidural anesthesia group and six (4.1%) in the PNB group developed deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism despite receiving prophylactic low molecular weight heparin. Thirty-two (22.1%) patients with postoperative delirium in PNB group was significant higher than 13 (11.5%) in epidural anesthesia group (χ2=4.922; P=0.027).

Preoperative and postoperative risk factors for mortality

Table 4 shows the univariate Cox regression analysis of the variables for mortality at 30 days and 1 year after surgery. Table 5 shows the results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis. In patients with acute cardiovascular events postoperatively, mortality was 39.3% (n=24) at 30 days (hazard ratio 6.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.0–11.2) and 78.7% (n=48) at 1 year (hazard ratio 4.4, 95% CI 3.1–9.3). In patients with acute respiratory events, mortality was 22.2% (n=6) at 30 days (hazard ratio 4.0, 95% CI 3.6–9.2) and 66.7% (n=18) at 1 year (hazard ratio 3.8, 95% CI 3.0–6.7).

Table 4.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of the variables for 30-day and 1-year mortality

| 30-day mortality | 1-year mortality | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1.8 (1.5–2.4)** | 1.5 (1.4–3.0)** |

| ICU admission | 1.9 (1.2–4.2) | 1.3 (0.7–2.1) |

| Age ≥85 years | 2.7 (1.4–5.2)* | 3.1 (2.2–5.3)* |

| Preoperative comorbidities | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.6 (1.2–1.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.8)* |

| Diabetes | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7)* |

| Respiratory disease | 1.9 (1.3–2.4)** | 1.6 (1.2–1.8)* |

| Stroke | 1.2 (1.1–1.7) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| Dementia | 2.0 (1.4–4.7)* | 2.5 (2.2–3.8) |

| Renal disease | 1.8 (1.3–4.0) | 2.2 (1.5–4.4)* |

| Hypoxia | 3.3 (0.8–13.2) | 1.8 (0.6–5.4) |

| Malignancy | 1.3 (1.0–2.1) | 1.6 (1.3–2.6)* |

| Comorbidities ≥3 | 2.1 (1.7–3.0) | 2.5 (2.0–3.6) |

| ASA ≥3 | 2.3 (1.9–3.4)** | 3.6 (2.6–5.0)** |

| Postoperative complications | ||

| Acute cardiovascular events | 8.1 (5.2–18.3)** | 6.5 (3.1–11.0)** |

| Myocardial infarction | 11.0 (2.3–56.7)** | 10.4 (2.0–56.1)** |

| Acute respiratory events | 7.5 (6.2–11.0)** | 5.1 (4.3–6.2)** |

| Stroke | 8.6 (4.6–17.0)** | 5.5 (3.3–8.4)* |

| Delirium | 1.8 (0.9–4.06) | 1.8 (0.9–4.2) |

| DVT/PE | 2.1 (1.1–4.6) | 2.6 (1.7–3.8) |

| Hypoxia | 2.8 (0.9–8.8)* | 2.0 (0.8–4.6) |

| Anemia | 0.9 (0.4–2.5) | 1.8 (0.9–3.8) |

| Deep wound infection | 0.4 (0–5.7) | 1.1 (1.3–3.4) |

| ≥3 complications | 13.8 (8.7–18.5)** | 6.8 (5.9–8.5)** |

Notes: Figures are hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals).

P<0.05;

P<0.01.

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ICU, intensive care unit; DVT/PE, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolus.

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the variables for 30-day and 1-year mortality

| 30-day mortality | 1-year mortality | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1.5 (1.1–2.0)* | 1.8 (1.6–3.5)** |

| ICU admission | 1.8 (1.1–4.1) | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) |

| Age ≥85 years | 1.7 (1.2–3.8) | 2.1 (1.6–4.3) |

| Preoperative comorbidities | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.8 (0.7–1.2) | 1.1 (0.9–1.8) |

| Diabetes | 1.0 (0.8–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7)* |

| Respiratory disease | 2.2 (1.7–3.2)* | 1.7 (1.2–2.8)* |

| Stroke | 1.0 (0.9–1.8) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) |

| Dementia | 1.8 (1.3–3.7) | 2.2 (2.0–3.8) |

| Renal disease | 1.6 (1.3–3.0)* | 1.4 (1.1–3.4)* |

| Hypoxia | 2.8 (1.8–7.4) | 1.3 (0.6–2.4) |

| Malignancy | 1.3 (1.1–2.3)* | 1.5 (1.2–2.8)** |

| Postoperative complications | ||

| Acute cardiovascular events | 6.2 (5.0–11.2)** | 4.4 (3.1–9.3)** |

| Myocardial infarction | 4.0 (2.5–6.6)** | 3.4 (2.0–4.1)** |

| Acute respiratory events | 4.0 (3.6–9.2)** | 3.8 (3.0–6.7)** |

| Stroke | 1.6 (1.2–5.3)** | 2.5 (2.1–5.4)* |

| Acute renal impairment | 2.0 (0.8–3.6) | 2.1 (1.1–3.8) |

| Hypoxia | 2.5 (0.9–4.8) | 1.8 (1.1–2.6) |

Notes: Figures are hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals).

P<0.05;

P<0.01.

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

After adjustment for age and sex, patients with three or more comorbidities had a hazard ratio of 2.1 for death (95% CI 1.7–3.0), males had a hazard ratio of 1.8 (95% CI 1.5–2.4), those with acute respiratory events had a hazard ratio of 1.9 (95% CI 1.3–2.4), and those with dementia had a hazard ratio of 2.0 (95% CI 1.4–4.7) at 30 days. Increasing age, admission to intensive care, and three or more postoperative complications were also key factors.

Discussion

In this study, we found in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality rates of 4.3%, 12.4%, and 22.9% in elderly patients undergoing hemiarthroplasty for FNF. One hundred and sixty-one (62.4%) patients had one or more postoperative complications, the most common being acute cardiovascular events, electrolyte disturbances, and hypoxemia. There was a higher incidence of acute respiratory events and fewer strokes in the PNB group. In-hospital mortality decreased slightly from 5.5% in the PNB group to 2.7% in the epidural anesthesia group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Within 30 days of surgery, 24 patients (39.3%) with acute cardiovascular events died, six (22.2%) with acute respiratory events died, and six patients (11.7%) with electrolyte disturbances died. Forty-eight patients (78.7%) with acute cardiovascular events died within 1 year. Preoperative parameters were not significantly different, except for more dementia and delirium in the PNB group. Waiting time to operation, length of postoperative hospital stay, hospital costs, duration of operation, intraoperative fluids required, and number of blood transfusions were not significantly different between the two groups. Admission to intensive care was more common in the PNB group. Older age, male sex, three or more comorbidities, acute cardiovascular events, acute respiratory events, three or more complications, and admission to intensive care were all risk factors for mortality.

The mortality at 30 days and at 1 year after surgery is similar to that in a previous study,2 and no significant difference was found in mortality rates between the two anesthetic techniques. Our results could be similar in terms of absolute risk to the findings of Urwin et al and O’Hara et al10,13 who reported a marginal 30-day survival advantage in favor of regional anesthesia in their meta-analysis. Further, male patients (n=14, 19.2%) had a significantly higher 30-day mortality than female patients (n=18, 9.7%; who live longer on average); this finding is consistent with another report.14 In this retrospective study, patients with acute cardiovascular and respiratory events had high mortality, with 24.8% (64) of geriatric patients developing cardiovascular or respiratory complications, which accounted for 32.8% (21) of deaths at 30 days after surgery. Closer scrutiny of the mortality data raises uncertainty. The likelihood of postoperative death is largely dependent on prefracture morbidity, so the potency of the anesthesia style was only slightly reflected in the mortality rate unless a subgroup analysis is performed in a large population of patients.15

One hundred and eighty-six patients (72.1%) had one or more comorbidities on admission. The most common were cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, and stroke. It appears that patients with certain preoperative comorbidities did not have serious postoperative complications. Previous research has indicated that myocardial infarction, dementia, and respiratory disease are associated with a greater risk of postoperative complications and can increase mortality.16 In our study, two patients had myocardial infarction after surgery, one of whom died during their in-hospital stay and the other died within 30 days of surgery. Two patients with perioperative stroke died in hospital, although they had been managed carefully and operated on successfully.

Seventeen patients (6.6%) in our study had dementia, which is thought to be associated with higher postoperative complication and mortality rates.17,18 Dementia was much common in the PNB group (9.7%) than in the epidural anesthesia group (2.7%).

Delirium is a syndrome characterized by acute onset of fluctuating levels of alertness or consciousness and a variety of other mental symptoms. In our study, 33 (12.8%) patients had delirium preoperatively, the reason for which might have been aging and trauma. Delirium (15.9%) was more common in the PNB group than in the epidural anesthesia group (8.8%).

Comparing the proportions of dementia and delirium between the two anesthesia groups, we speculated that mental status may affect the choice of anesthesia in elderly patients. Accordingly, the lower mortality seen in the epidural anesthesia group could not be fully attributed to the type of anesthesia given.

Although there is little presurgical blood loss in patients with FNF, hypovolemia is poorly tolerated by the frail elderly. A retrospective study of over 8,000 elderly patients with hip fracture found that perioperative transfusion had no influence on mortality risk in patients with hemoglobin concentrations >80 g/L,19 although there is some evidence that transfusion at higher hemoglobin concentrations for patients with known cardiac disease may be beneficial.20 Correction of anemia with blood transfusion is fraught with debate.

Further, persistent hypoxia may be present in all patients with hip fracture from the time of admission up until several days postoperatively.21 In our study, 38 (14.7%) patients were hypoxemic when the first arterial blood sample was drawn, and 30 (78.9%) of these patients still had arterial oxygen pressure below 60 mmHg after surgery. Anemia, hypoxemia, and hypoproteinemia invariably occur concomitantly, and may be associated with increased postoperative complications and mortality.22 As such, an appropriate transfusion threshold in the elderly that would limit risk and optimize benefit would be advantageous. In our department, all patients breathed oxygen (3–5 L/min) continuously before and after surgery. The hemoglobin level signaling a need for transfusion should be 90 g/L in geriatric patients.

Electrolyte disturbances were common preoperatively (24; 9.3%) and postoperatively (54; 20.9%) in our study. Hypokalemia was the most common electrolyte abnormality, and was intractable even when intravenous and oral potassium supplements were given. Seven (13.0%) patients with postoperative electrolyte disturbances died within 30 days of surgery.

Hip fracture patients have the highest risk of concomitant delirium, with a reported incidence of 35%–50%.8,18 In our study, the incidence was 22.1 (32) postoperatively in the PNB group, and was much higher than in the epidural anesthesia group (χ2=4.922; P=0.027). Nevertheless, the higher incidence of preoperative delirium and dementia in the PNB group could have affected the postoperative outcome.

Admission to intensive care in the PNB group (29; 20%) was more common than in the epidural anesthesia group (11; 9.7%). As would be expected, we found that admission to intensive care was positively associated with increased mortality at the observed time points. Patients in intensive care incurred higher hospital costs and had a longer postoperative hospital stay.

The duration of surgery was not significantly different between the two anesthesia groups (104±33 minutes in the PNB group versus 100±27 minutes in the epidural anesthesia group; P=0.275). A previous report indicated that epidural anesthesia can provide optimal muscle relaxation, which makes dissection and placement of the prosthesis easier to perform.23

In our study, no significant differences were found between the groups for blood loss (382±170 mL versus 422±194 mL; P=0.084) or blood transfusion (4.19±3.21u versus 3.94±2.64u). A meta-analysis has shown that many studies have demonstrated there was less blood loss in patients who had undergone epidural anesthesia.19 However, these reports compared blood loss between regional anesthesia and general anesthesia, and we are the first to compare blood loss between two regional anesthetic techniques. As mentioned in previous reports,19 blood loss in our epidural anesthesia group might be attributable to decreased blood pressure. Unfortunately, we did not analyze perioperative blood pressure between the groups due to the limited recording data available.

Waiting time to surgery was longer, with some surgeries being delayed for up to 1 week in our study. Empirical evidence demonstrates that decreasing the waiting time to surgery decreases mortality.24,25 However, there are some recent data showing no significant difference in mortality between patients having early or delayed surgery.26 Some trauma patients did not have adequate physiologic reserve and remained under resuscitated before surgery. These fragile patients given earlier surgery could increase postoperative complications. Hence, suitable preoperative preparation and optimized medical conditions could optimize the outcomes.

It has been reported that deep vein thrombosis may be less frequent in patients who have had a hip fracture and been given regional anesthesia. However, the group had no anticoagulation in its study.23 In our department, all patients undergoing lower limb surgery must have prophylactic anti-coagulation with low molecular weight heparin, consistent with the report by Geerts et al.27 We did not find a difference in occurrence of thrombosis between the two regional anesthetic techniques (P=0.658).

The length of postoperative hospital stay was not significantly different between the two groups (P=0.557), despite the higher number of admissions to intensive care in the PNB group. Further, there was no significant difference in hospital costs between the epidural anesthesia group and the PNB group. Costs excluding procedural and equipment charges are more dependent on preoperative comorbidities and care for postoperative complications. However, the cost of hospitalization increased with delays in surgery, longer postoperative hospital stay, and admission to intensive care, which is consistent with previous reports.28

With the development of ultrasonographic imaging and neurostimulation technology, more anesthesiologists are tending to select PNB for lower limb surgery.29 Use of PNB increased sharply at our institution from 14.3% to 52.7% during our 5-year study period. PNB with propofol sedation is a sophisticated technique, and is generally implemented at our hospital. The technique is neither solely regional anesthesia nor general anesthesia, but is a combination of both, and involves administration of balance anesthesia, with or without an oropharynx parichnos or laryngeal mask. Perioperative hemodynamic stability and improved postoperative analgesia could have decreased the incidence of cardio-cerebrovascular and respiratory complications.13,30

We recognize that our study has some limitations. First, it was retrospective in nature and used an ad ministrative database that may be subject to inaccuracies in coding, which could have influenced our results. Some “atypical” complications are more common in elderly patients, and some patients who were treated conservatively without surgery had extremely high mortality. This data was not recorded and therefore was not analyzed. Furthermore, the sicker patients were more likely to be given PNB anesthesia. However, our findings may reflect selection bias, hence, the accurate mortality is inconsistent to our existent data. Our exclusion of patients who did not undergo surgery along with those who received general anesthesia may limit the generalizability of our results. Third, postoperative functional recovery is also an important outcome in elderly patients, but could not be investigated in this retrospective study. Finally, the small sample size and single-center nature of our study made it difficult to appreciate significant differences between the two study groups.

Conclusion

Our study shows that PNB is not associated with lower mortality or cardiovascular complication rates than epidural anesthesia in patients receiving hemiarthroplasty for FNF. Patients who received PNB were more likely to have dementia and acute respiratory events postoperatively than those who received epidural anesthesia, and those who had epidural anesthesia were more likely to have a stroke postoperatively. It is possible that perioperative management might be more important than the type of anesthesia administered. Therefore, further studies should aim to identify optimal management for these patients to improve their outcome using a team-based approach, and then use best practice guidelines and standardized outcome measures.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many research staff members, nursing staff, and their surgical and anesthesiology colleagues at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital who helped with the conduct of the study, especially Qun Zhang and Yonggang Zhou in the Department of Orthopaedics. They are also grateful to Zhi Li (Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, People’s Republic of China) for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Roberts SE, Goldacre MJ. Time trends and demography of mortality after fractured neck of femur in an English population, 1968–1998: database study. BMJ. 2003;327(7418):771–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kesmezacar H, Ayhan E, Unlu MC, Seker A, Karaca S. Predictors of mortality in elderly patients with an intertrochanteric or a femoral neck fracture. J Trauma. 2010;68(1):153–158. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819adc50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(3):364–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tidermark J. Quality of life and femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 2003;74(309):1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker MJ, Gurusamy K. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for intra-capsular proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001708. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001708.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White SM, Griffiths R, Holloway J, Shannon A. Anaesthesia for proximal femoral fracture in the UK: first report from the NHS Hip Fracture Anaesthesia Network. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(3):243–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, et al. Reduction of postoperative mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anaesthesia: results from overview of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321(7275):1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Hara DA, Duff A, Berlin JA, et al. The effect of anesthetic technique on postoperative outcomes in hip fracture repair. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(4):947–957. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler SJ, Symons J, Sabato S, Myles PS. Epidural analgesia compared with peripheral nerve blockade after major knee surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(2):154–164. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler J, Marhofer P, Hopkins PM, Hollmann MW. Peripheral regional anaesthesia and outcome: lessons learned from the last 10 years. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(5):728–745. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urwin SC, Parker MJ, Griffiths R. General versus regional anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(4):450–455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eiskjaer S, Ostgard SE. Risk factors influencing mortality after bipolar hemiarthroplasty in the treatment of fracture of the femoral neck. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;270:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foss NB, Kehlet H. Mortality analysis in hip fracture patients: implications for design of future outcome trials. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(1):24–29. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirksen A, Kjoller E. Cardiac predictors of death after non-cardiac surgery evaluated by intention to treat. BMJ. 1988;297(6655):1011–1013. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6655.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riis J, Lomholt B, Haxholdt O, et al. Immediate and long-term mental recovery from general versus epidural anesthesia in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983;27(1):44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1983.tb01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams-Russo P, Sharrock NE, Mattis S, Szatrowski TP, Charlson ME. Cognitive effects after epidural vs general anesthesia in older adults. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1995;274(1):44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carson JL, Duff A, Berlin JA, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and postoperative mortality. JAMA. 1998;279(3):199–205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson AH, Fleisher LA, Rosenbaum SH. Relationship between postoperative anemia and cardiac morbidity in high-risk vascular patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(6):860–866. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyson A, Henderson AM, Chamley D, Campbell ID. An assessment of postoperative oxygen therapy in patients with fractured neck of femur. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1988;16(4):405–410. doi: 10.1177/0310057X8801600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foss NB, Kristensen MT, Kehlet H. Anaemia impedes functional mobility after hip fracture surgery. Age Ageing. 2008;37(2):173–178. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hole A, Terjesen T, Breivik H. Epidural versus general anaesthesia for total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1980;24(4):279–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1980.tb01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma PT, Sieber FE, Zakriya KJ, et al. Recovery room delirium predicts postoperative delirium after hip-fracture repair. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(4):1215–1220. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000167383.44984.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison RS, Magaziner J, McLaughlin MA, et al. The impact of post-operative pain on outcomes following hip fracture. Pain. 2003;103(3):303–311. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00458-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.March LM, Chamberlain AC, Cameron ID, et al. How best to fix a broken hip. Fractured Neck of Femur Health Outcomes Project Team. Med J Aust. 1999;170(10):489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):338S–400S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.338S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi N, Foley K, Lenhart G, Badamgarav E. Direct healthcare costs of hip, vertebral, and non-hip, non-vertebral fractures. Bone. 2009;45(6):1084–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beaupre LA, Jones CA, Saunders LD, Johnston DW, Buckingham J, Majumdar SR. Best practices for elderly hip fracture patients. A systematic overview of the evidence. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bode RH, Jr, Lewis KP, Zarich SW, et al. Cardiac outcome after peripheral vascular surgery. Comparison of general and regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(1):3–13. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]