Abstract

The essential oil of Clausena anisum-olens (Blanco) Merr. showed strong contact toxicity and repellency against Lasioderma serricorne and Liposcelis bostrychophila adults. The components of the essential oil obtained by hydrodistillation were determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. It was found that the main components were myristicin (36.87%), terpinolene (13.26%), p-cymene-8-ol (12.38%), and 3-carene (3.88%). Myristicin and p-cymene-8-ol were separated by silica gel column chromatography, and their molecular structures were confirmed by means of physicochemical and spectrometric analysis. Myristicin and p-cymene-8-ol showed strong contact toxicity against L. serricorne (LD50 = 18.96 and 39.68 μg per adult) and Li. bostrychophila (LD50 = 20.41 and 35.66 μg per adult). The essential oil acting against the two grain storage insects showed LD50 values of 12.44 and 74.46 μg per adult, respectively. Myristicin and p-cymene-8-ol have strong repellent toxicity to Li. bostrychophila.

Keywords: Clausena anisum-olens, contact toxicity, repellency, Lasioderma serricorne, Liposcelis bostrychophila

The cigarette beetle, Lasioderma serricorne (F.) (Coleoptera: Anobiidae), is one of the major pests of durable grain commodities, spices, and stored tobaccos. Its larvae cause feeding damage mostly to commodities and its adults rarely feed and are good fliers (Mahroof 2013). The booklouse, Liposcelis bostrychophila Badonnel (Psocoptera: Liposcelididae), has a worldwide distribution. It is popularly found in stored-product grains and amylaceous products (Nayak et al. 2005). They have been regarded as the secondary pests, due to their small size and the great damages in cereal grains (Turner 1998). Currently, psocid is perhaps the most important category of emerging pests in stored grains and related commodities in China (Li et al. 2011b).

Control of stored product insects relies heavily on the use of synthetic insecticides and fumigants, which has led to problems such as disturbances of the environment, increasing costs of application, pest resurgence, pest resistance to pesticides, and lethal effects on nontarget organisms in addition to direct toxicity to users (Isman 2004). The widespread extensive use of synthetic insecticides has led to many negative consequences, resulting in increasing attention being given to natural products (Zhang et al. 2011). Botanical pesticides have the advantage of providing novel modes of action against insects that can reduce the risk of cross-resistance and offer new leads for design of target-specific molecules (Li et al. 2011a). Investigations in several countries confirmed that some plant essential oils not only repelled insects but also possessed contact and fumigant toxicities against stored product pests. Moreover, these plant essential oils can exhibit feeding inhibition or harmful effects on the reproductive system of insects (Isman 2006). Essential oils and their constituents have been evaluated for repellent and insecticidal activities against stored product insects or mites, and some of them are quite promising in the development of natural repellents or insecticides (Lee et al. 2006, Liu et al. 2007, Zoubiri and Baaliouamer 2011, Liang et al. 2013). During the screening program for new agrochemicals from Chinese medicinal herbs, essential oil derived from dried rhizome of Clausena anisum-olens (Blanco) Merr. (Family: Rutaceae) was found to possess strong insecticidal and repellent activities against the stored product insects.

C. anisum-olens is a shrub that grows wildly and is cultivated in Southeast Asia countries such as Philippines and South China. Its aerial parts have been used for the treatment of dysentery and arthritis (Institutum Botanicum Kunmingenge Academiae Sinicae 2001). To date, coumarins and cyclopeptides were isolated from the leaves and twigs of this plant (Wang et al. 2008a,b, 2009a,b). The compositions of C. anisum-olens essential oil were also analyzed previously (Molino 2000, Su and Liang 2011). However, there is no report on isolation of C. anisum-olens essential oil and insecticidal activity of the essential oil against stored product insects.

Materials and Methods

Chinese Medicinal Herb and Extractions

Dried leaves of C. anisum-olens (3.0 kg) were collected in May 2013 from Yulin City, Guangxi Autonomous Region, (Guangxi 537000, China, 22.38° N latitude and 106.42° E longitude). A voucher specimen (BNU-HSL-Dushushan- 2013-05-29-017) was deposited in the College of Resources Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China. The dried leaves were ground to a powder. The hydrodistillation of the sample was performed in a modified Clevenger-type apparatus for 6 h. The raw oil was extracted with hexane and then dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. The essential oil was stored in airtight containers in a refrigerator at 4°C.

Insects

The insects were obtained from laboratory cultures maintained for the last 2 yr in the dark, in incubators at 29–30°C, and 70–80% relative humidity. L. serricorne was reared on wheat flour mixed with yeast (10:1, w/w) at 12–13% moisture content, and Li. bostrychophila was reared on a 1:1:1 mixture, by mass, of milk powder, active yeast, and flour. Adult insects used in the experiments were 1–2 wk old.

Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Components of the essential oil were separated and identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on an Agilent 6890N apparatus equipped with FID and an Agilent 5973N mass selective detector. They were equipped with a flame ionization detector (280°C) and fitted with a HP-5MS column (30 m by 0.25 mm, df = 0.25 µm). The GC settings were as follows: initial oven temperature was held at 60°C for 1 min, and then ramped at 10°C/min to 180°C for 1 min and then ramped at 20°C/min to 280°C for 15 min. The injector temperature was maintained at 270°C. The samples (1 µl) were injected neat, with a split ratio of 1:10. The spectra were scanned from 20 to 550 m/z at two scans s−1. Most constituents were identified by GC by comparison of their retention indices with those of the literature (Rui and Ji 1992, Wang et al. 1994, Shi et al. 2011) or with those of authentic compounds available in our libraries (Wiley and NIST databases). The retention indices were determined in relation to a homologous series of n-alkanes (C8-C24) under the same operating. Component relative percentages were calculated based on GC peak areas for each component.

Bioassay-Directed Fractionation

The crude essential oil (7 ml) was chromatographed on a silica gel column (3 cm in i.d., 35 cm in length) by gradient elution with a mixture of solvents (petroleum ether, petroleum ether-ethyl acetate, from 100:1,…, 100:50). Fractions of 250 ml were collected and concentrated at 40°C, and similar fractions were combined to yield 30 fractions according to thin layer chromatography profiles. Fractions 2–4 that possessed contact/repellency toxicity, with similar thin layer profiles, were polled and further purified by preparative silica gel column chromatography to obtain one pure compound for determining structure as p-cymene-8-ol (0.8 g). Fraction 13 that possessed contact and repellency toxicity was further purified by preparative silica gel column chromatography to obtain myristicin (1.7 g). 1H- and 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data were recorded on Bruker Avance DRX 500 NMR spectrometer with TMS (Tetramethylsilane) as the internal standard using deuterochloroform (CDCl3) as the solvent.

Contact Toxicity

The contact toxicity of essential oil against L. serricorne adults was measured as described by Liu and Ho (1999). Range-finding studies were run to determine the appropriate testing concentrations. A serial dilution of the essential oil was prepared in n-hexane. Aliquots of 0.5 μl of the dilutions were applied topically to the dorsal thorax of the insects. Both treated and control insects were then transferred to glass vials (10 insects per vial) with culture medium and kept in incubators. The mortality of the insects was observed after 24 h. The LD50 values were calculated by using probit analysis (Sakuma 1998). The positive control, pyrethrum extract (25% pyrethrine I and pyrethrine II), was purchased from Fluka Chemie, St.Louis, USA.

The contact toxicity of the essential oil against Li. bostrychophila was measured as described by Zhou et al. (2012). A 5.5 cm diameter filter paper was treated with 150 µl of the solution of the essential oil. The filter paper after being treated with solid glue was placed in a 5.5 cm diameter Petri dish and 10 booklice were put on the filter paper. A cover was put and all the Petri dishes were kept in incubators. n-Hexane was used as a negative control. Five concentrations (in n-hexane) and five batches of each concentration were used. The experiment was repeated twice. Mortality of insects was observed after 24 h. The LD50 values were calculated by using Probit analysis (IBM SPSS V20.0) (Sakuma 1998).

Repellent Toxicity

A commercial repellent, DEET (N, N-diethyl-3-methyl benzamide) was purchased from National Center of Pesticide Standards (Shenyang, China) and used as a positive control. Petri dishes 6 cm in diameter were used to confine Li. bostrychophila during the experiment. The essential oil of C. anisum-olens and the isolated compounds were diluted in n-hexane to different concentration (31.58, 6.32, 1.26, 0.25, 0.05 nl/cm2), and n-hexane was used as the control. Filter papers, 6 cm in diameter, were cut in half and 150 μl of each concentration was applied separately to one-half of the filter paper as uniformly as possible with a micropipette. The other half (control) was treated with 150 μl of n-hexane. Both the treated and the control half were then air dried to evaporate the solvent completely (30 s). A full disc was carefully remade by attaching the tested half to the negative control half with tape. Each remade filter paper after being treated with solid glue was placed in a Petri dish. The solid glue was used to attach filter paper to the dish. Twenty insects were released in the center of each filter paper disc, and a cover was placed over the Petri dish. Five batches were used, and the experiment was repeated twice. Counts of the insects present on each strip were made after 2 h and 4 h. The percent repellency of each volatile oil or compound was then calculated using the formula:

where Nc was the number of insects present in the negative control half, while Nt was the number of insects present in the treated half.

The averages were then assigned to different classes (0–V) using the following scale (percentage repellency) (Liu and Ho 1999). Class, % repellency: 0, >0.01 to <0.1; I, 0.1–20.0; II, 20.1–40.0; III, 40.1–60.0; IV, 60.1–80.0; and V, 80.1–100.

In the experiments with L. serricorne, dishes and filter papers were changed to 9 cm in diameter and the concentration of the oils and isolated constituents were 39.32, 7.86, 1.57, 0.31, and 0.06 nl/cm2. The half filter paper was treated with 500 μl of the solution. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test were conducted by using SPSS 20.0 for Windows 2007. Percentage was subjected to an arcsine square-root transformation before ANOVA and Tukey’s tests.

Results

Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil

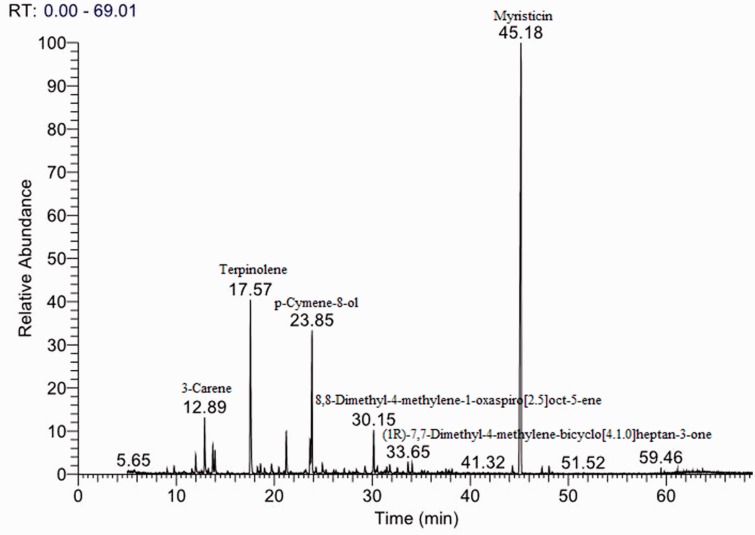

Yield of the C. anisum-olens essential oil from air-dried leaves was 0.35% (v/w). A total of 27 major components of the essential oil were identified, accounting for 84.29% of the total components present (Table 1). The main components were myristicin (36.87%), terpinolene (13.92%), and p-cymene-8-ol (12.38%) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Chemical constituents of the essential oil derived from C. anisum-olens leaves

| No. | Compounds | RIa | Chemical formula | Peak area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Pinene | 931 | C10H16 | 0.27 |

| 2 | α-Fenchene | 938 | C10H16 | 0.14 |

| 3 | Myrcene | 988 | C10H16 | 1.16 |

| 4 | α-Phellandrene | 999 | C10H16 | 0.19 |

| 5 | 3-Carene | 1,004 | C10H16 | 4.07 |

| 6 | Isoterpinolene | 1,063 | C10H16 | 0.34 |

| 7 | o-Cymene | 1,070 | C10H14 | 1.92 |

| 8 | β-Terpinyl acetate | 1,079 | C12H20O2 | 1.56 |

| 9 | Terpinolene | 1,083 | C10H16 | 13.92 |

| 10 | Benzylin | 1,138 | C15H14O3 | 0.22 |

| 11 | 1,5,8-p-Menthatriene | 1,142 | C10H14 | 2.27 |

| 12 | 4-methylacetophenone | 1,150 | C9H10O | 2.13 |

| 13 | p-Cymene-8-ol | 1,183 | C10H14O | 12.38 |

| 14 | 1-(4-Methylphenyl)ethanol | 1,202 | C9H12O | 0.77 |

| 15 | Cinerone | 1,227 | C10H14O | 0.29 |

| 16 | 1-Cyclopentylcyclopentene | 1,258 | C10H16 | 0.17 |

| 17 | 8,8-Dimethyl-4-methylene-1-oxaspiro[2.5]oct-5-ene | 1,286 | C10H14O | 1.65 |

| 18 | 2,6-Dimethyl-3,5,7-octatriene-2-ol | 1,306 | C10H16O | 0.57 |

| 19 | 6-Isopropylidene-bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane | 1,321 | C9H14 | 0.28 |

| 20 | 4,4a,5,6-Tetrahydro-4, 7-dimethyl- cyclopenta[c]pyran-1,3-dione | 1,355 | C10H13O3 | 0.53 |

| 21 | 1-(1,1-Dimethylethoxy)-2-methyl-1-cyclohexene | 1,372 | C11H20O | 0.45 |

| 22 | (1R)-7,7-Dimethyl-4-methylene-bicyclo[4.1.0]heptan-3-one | 1,396 | C10H14O | 0.16 |

| 23 | Methyl eugenol | 1,401 | C11H14O2 | 0.34 |

| 24 | Myristicin | 1,489 | C11H12O3 | 36.87 |

| 25 | β-Bisabolene | 1,504 | C15H24 | 0.55 |

| 26 | Elemicin | 1,551 | C12H16O3 | 0.50 |

| 27 | Spathulenol | 1,563 | C15H24O | 0.59 |

| Total | 84.29 |

aRI, retention index as determined on a HP-5MS column using the homologous series of n-hydrocarbon.

Fig. 1.

GC chromatograph of separated compounds from C. anisum-olens essential oil.

Isolated Compounds

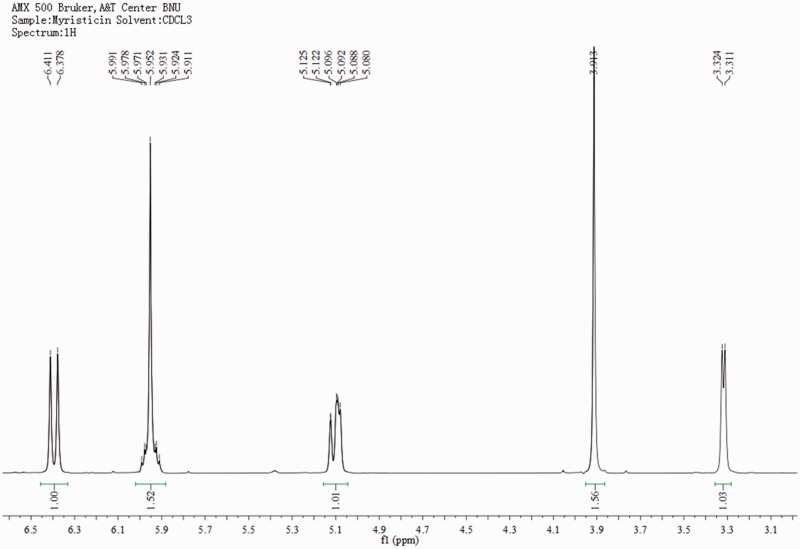

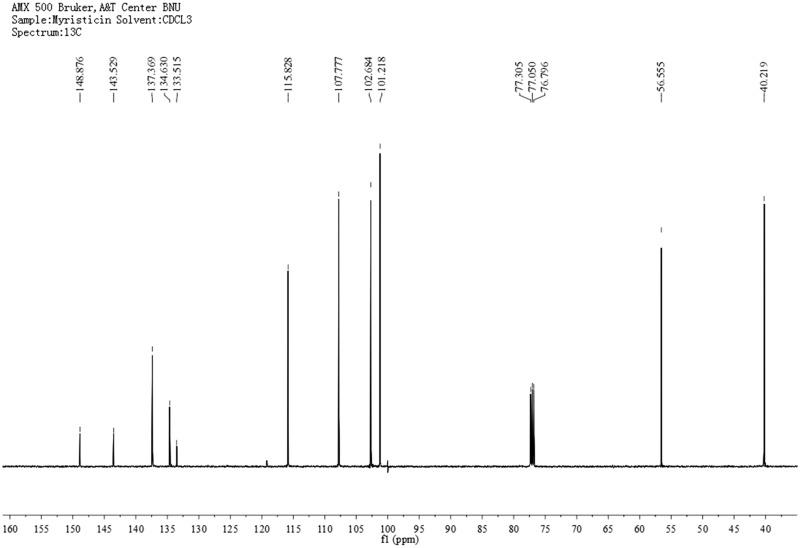

\Based on bioassay-guided fractionation, two compounds were separated and purified by column chromatography and preparative thin layer chromatography. The identifications were supported by the following data: Myristicin (1, Fig. 2), slightly yellow oil, C11H12O3. 1H-MNR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.32 (2H, d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1-CH2), 3.91 (3H, s, 3'-OCH3), 5.09 (2H, m, 3-CH2), 5.95 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 5.96 (1H, m, 2-H), 6.38 (1H, s, 6'-H), 6.41(1H, s, 2'-H). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 40.2 (C-1), 56.6 (C-OCH3), 101.2 (O-CH2-O), 102.7 (C-6'), 107.8 (C-2'), 115.8 (C-3), 133.5 (C-1'), 134.6 (C-4') 137.3 (C-2), 143.5 (C-3'), 148.8 (C-5'). 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra are presented in Figures 3 and 4. Its NMR data were in accord with the reported data of Passreiter et al. (2005).

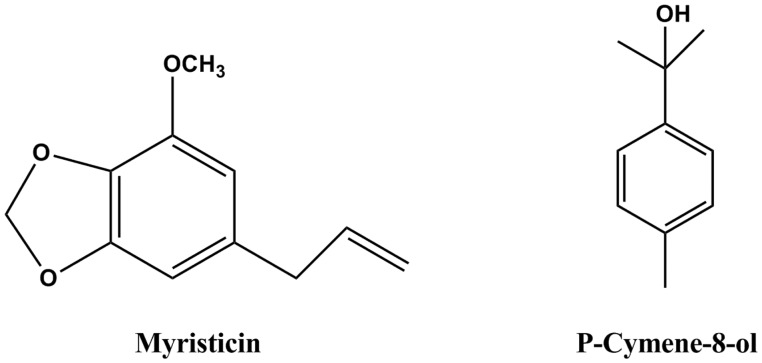

Fig. 2.

Structure of myristicin and p-cymene-8-ol isolated from C. anisum-olens essential oil.

Fig. 3.

The 1H-NMR spectra of myristicin.

Fig. 4.

The 13C-NMR spectra of myristicin.

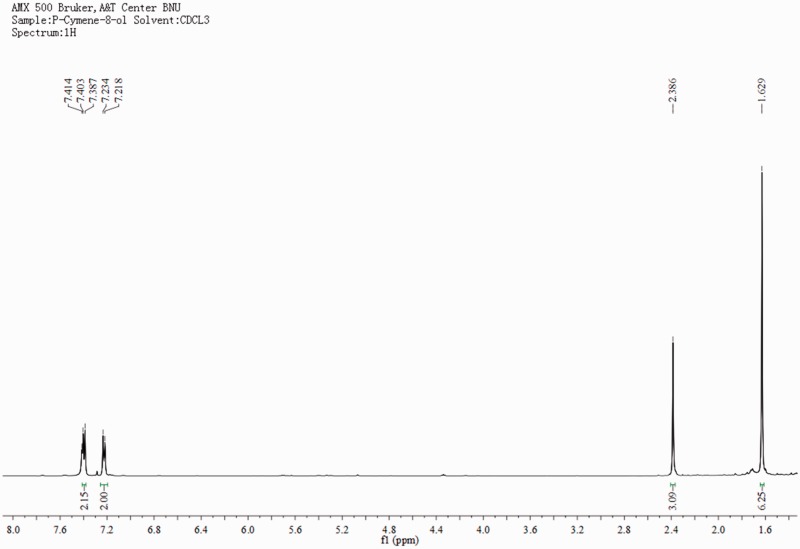

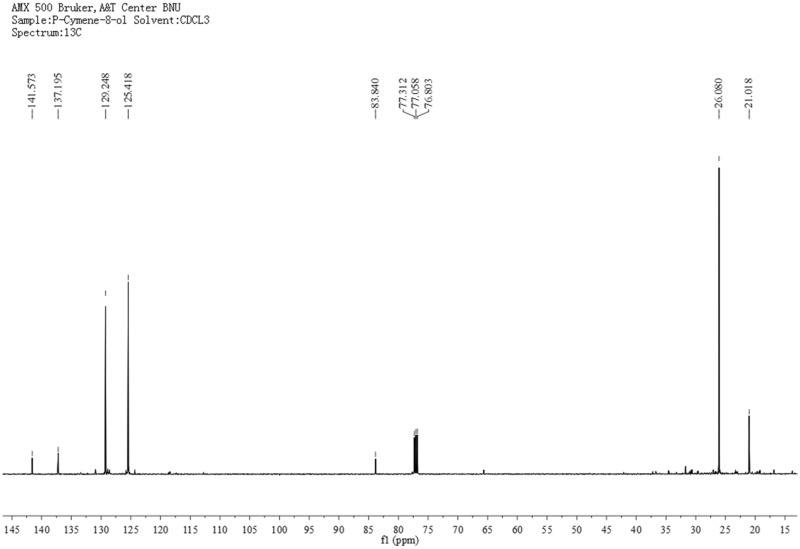

P-Cymene-8-ol (2, Fig. 2), slightly yellow oil, C10H14O. 1H-MNR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.63 (6H, s, CH3-C-CH3), 2.39 (3H, s, 1-CH3), 7.23 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3-H and 5-H), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2-H and 6-H). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 21.0 (C-CH3), 26.1 (CH3-C-CH3), 83.8 (C-1'), 125.4 (C-3 and C-5), 129.2 (C-2 and C-6), 137.2 (C-1), 141.6 (C-4). 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra are presented in Figures 5 and 6. The above data were identical to the published data of Gurudutt et al. (1984) and Yamamoto et al. (2011).

Fig. 5.

The 1H-NMR spectra of p-cymene-8-ol.

Fig. 6.

The 13C-NMR spectra of p-cymene-8-ol.

Insecticidal Toxicity

Myristicin showed stronger contact toxicity against L. serricorne (LD50 = 18.96 μg per adult) and Li. bostrychophila (LD50 = 20.41μg per adult) than p-cymene-8-ol (LD50 = 39.68 and 35.66 μg per adult, respectively), while the essential oil of C. anisum-olens possessed contact toxicity against L. serricorne and Li. bostrychophila with LD50 values of 12.44 μg per adult and 74.46 μg per adult, respectively. However, when compared with the positive control, the essential oil of C. anisum-olens had 52 and 4 times less acute toxicity against the two species of grain storage insects (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Contact toxicity of the essential oil of C. anisum-olens against L. serricorne

| Insects | Treatments | LD50 (μg/adult) | 95% fiducial limits | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. serricorne | C. anisum-olens | 12.44 | 6.37 ± 17.14 | 17.36 |

| Myristicin | 18.96 | 16.20 ± 21.75 | 19.78 | |

| p-cymene-8-ol | 39.68 | 33.47 ± 45.55 | 16.79 | |

| Pyrethrum extract | 0.24 | 0.16 ± 0.35 | 16.33 |

Table 3.

Contact toxicity of the essential oil of C. anisum-olens against Li. bostrychophila

| Insects | Treatments | LD50 (μg/cm2) | 95% fiducial limits | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li. bostrychophila | C. anisum-olens | 74.46 | 67.16–79.31 | 21.16 |

| myristicin | 20.41 | 18.81–22.07 | 20.93 | |

| p-cymene-8-ol | 35.66 | 32.62–39.07 | 19.32 | |

| Pyrethrum extract | 18.99a | — | — |

aData from Liu et al. (2013b).

Repellent Activity

The results of repellency assays for the essential oil and isolated constituents against the two species of insects were presented in Tables 4 and 5. Data showed that C. anisum-olens exhibited strong repellency against L. serricorne and L. bostrychophila. At the test concentration of 39.32 nl/cm2, the essential oil and the positive control, DEET showed the same level repellency against L. serricorne at 2 h/4 h after exposure, whereas at the test concentrations of 1.57 and 0.31 nl/cm2, the essential oil exhibited stronger repellency (38% and 32%, respectively) than DEET (28% and 20%, respectively) against L. serricorne at 2 h after exposure. However, at the test concentrations of 39.32 and 6.32 nl/cm2, the essential oil and DEET also showed the same level repellency against Li. bostrychophila at 2 h/4 h after exposure (class V).

Table 4.

Percentage repellency after two exposure times for the essential oil and isolated constituents against L. serricornea (df = 3)

| Treatment | 2 h |

4 h |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39.32b | 7.86b | 1.57b | 0.31b | 0.06b | 39.32b | 7.86b | 1.57b | 0.31b | 0.06b | |

| C. anisum-olens | 96 ± 4a | 54 ± 12bc | 38 ± 10b | 32 ± 7a | 12 ± 7a | 86 ± 6b | 30 ± 9c | 10 ± 6b | 2 ± 3b | −26 ± 6c |

| Myristicin | 78 ± 5bc | 72 ± 9ab | 68 ± 10a | 4 ± 3b | −18 ± 7b | 80 ± 12b | 50 ± 6b | −8 ± 5c | −46 ± 7c | −60 ± 6d |

| p-cymene-8-ol | 64 ± 9c | 46 ± 4c | 22 ± 3b | 14 ± 4ab | 6 ± 4a | 58 ± 9c | 50 ± 10b | 16 ± 9b | 8 ± 7b | 4 ± 3b |

| DEET | 88 ± 7ab | 76 ± 14a | 28 ± 7b | 20 ± 14ab | 16 ± 7a | 98 ± 4a | 78 ± 9a | 58 ± 16a | 56 ± 14a | 46 ± 7a |

| F | 10.347 | 4.412 | 12.318 | 3.575 | 26.006 | 8.759 | 13.803 | 21.096 | 78.738 | 165.515 |

| P | 0 | 0.019 | 0 | 0.038 | 0 | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aMeans in the same column followed by the same letters do not differ significantly (P < 0.05) in ANOVA. PR was subjected to an arcsine square-root transformation before ANOVA.

bConcentration (nl/cm2).

Table 5.

Percentage repellency after two exposure times for the essential oil and isolated constituents against Li. bostrychophilaa (df = 3)

| Treatment | 2 h |

4 h |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31.58b | 6.32b | 1.26b | 0.25b | 0.05b | 31.58b | 6.32b | 1.26b | 0.25b | 0.05b | |

| C. anisum-olens | 94 ± 3b | 86 ± 4b | 42 ± 8c | 22 ± 5b | 14 ± 7a | 92 ± 8a | 68 ± 7b | 32 ± 8c | 16 ± 15b | 12 ± 10ab |

| Myristicin | 90 ± 4b | 100 ± 0a | 94 ± 3a | 54 ± 7a | 22 ± 10a | 96 ± 3a | 98 ± 3a | 92 ± 7a | 20 ± 18b | 6 ± 10b |

| p-cymene-8-ol | 100 ± 0a | 96 ± 7a | 32 ± 11c | 22 ± 11b | 18 ± 7a | 96 ± 7a | 74 ± 16b | 30 ± 10c | 18 ± 11b | 16 ± 4ab |

| DEET | 100 ± 0a | 98 ± 3a | 78 ± 10b | 66 ± 8a | 8 ± 3a | 96 ± 3a | 82 ± 5b | 68 ± 3b | 54 ± 6a | 22 ± 5 a |

| F | 6.806 | 8.058 | 24.249 | 15.694 | 1.491 | 0.149 | 7.592 | 27.069 | 2.979 | 2.383 |

| P | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0.255 | 0.929 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.063 | 0.108 |

aMeans in the same column followed by the same letters do not differ significantly (P < 0.05) in ANOVA. PR was subjected to an arcsine square-root transformation before ANOVA.

bConcentration (nl/cm2).

Myristicin and p-cymene-8-ol had strong repellent toxicity against Li. bostrychophila and moderate repellency against L. serricorne. Compared with the positive control, at the concentration of 1.26 nl/cm2, myristicin exhibited stronger repellency (92%, class V) than DEET (68%, class IV) against Li. bostrychophila at 4 h after exposure. Moreover, at the concentration of 1.57 nl/cm2, myristicin showed strongly repellent (68%, class IV) against L. serricorne, while the positive control showed less repellency (28%, class II) at 2 h after exposure. When at the test c, p-cymene-8-ol possessed the same level repellency against Li. bostrychophila relative to DEET at 2 h and 4 h after exposure (class V).

Discussion

Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil

The main components of the essential oil of C. anisum-olens were myristicin (36.87%), terpinolene (13.92%), and p-cymene-8-ol (12.38%). The chemical composition of the essential oil of C. anisum-olens in this study was not the same as what had been reported in previous studies. For example, Su and Liang (2011) found that the essential oil of C. anisum-olens leaves collected from Fusui of Guangxi Province contained myristicin (28.97%) and (+) - 4 - carene (24.84%). Moreover, there were some variations in the essential oil derived from different parts of C. anisum-olens. Su et al. (2011) indicated that the major components of the essential oil of C. anisum-olens nutlets harvested from Longzhou of Guangxi Province were myristicin (47.07%), 1,2,3-trimethoxy-5-(2-propenyl)-benzene (8.25%), 2,6-dimethoxy-4-(2-propenyl)-pheno (7.17%), and n-hexadecanoic acid (7.05%). These differences of chemical content and composition of the essential oils might have been due to different parts, harvest time, local, season factors, and storage duration, and these differences may result in different biological activities. The above results suggested further studies on plant cultivation and essential oil standardization were needed.

Insecticidal Toxicity

The essential oil of C. anisum-olens showed stronger contact toxicity against L. serricorne than the isolated compounds, which had almost 1.5 and 3 times more toxicity than myristicin and p-cymene-8-ol against L. serricorne. The results indicated that the contact toxicity of the essential oil against L. serricorne was related to the synergistic effects of its diverse major and minor components. Myristicin had almost 2 and 1.7 times more toxicity than p-cymene-8-ol against L. serricorne and Li. bostrychophila, respectively. It is suggested that myristicin is a major contributor to the contact toxicity of the essential oil against L. serricorne and Li. bostrychophila.

The essential oil showed weaker contact toxicity against L. serricorne and Li. bostrychophila than the positive control. However, when compared with other essential oils, C. anisum-olens essential oil possessed stronger contact toxicity against the two stored product insects, e.g., essential oils of Litsea cubeba (LD50 = 27.33 μg per adult) against L. serricorne (Yang et al. 2014), Cinnamomum camphora (LD50 = 21.25 μg per adult) against L. serricorne (Chen et al. 2014), Acorus calamus (LD50 = 100.21 μg per cm2) against Li. bostrychophila (Liu et al. 2013b), and Artemisia rupestris (LD50 = 418.48 μg per adult) against Li. bostrychophila (Liu et al. 2013a).

As currently used insecticides are generally synthetic and the most effective of which (e.g., phosphine and methyl bromide) are also highly toxic to humans and other nontarget organisms. The essential oil of C. anisum-olens leaves and its active compounds show potential to be developed into possible natural insecticides for the control of two stored product insects. However, the dose rates of the essential oil and isolated compounds used here were high when compared with the concentrations of the positive control. So the practical application of the essential oil and the isolated compounds as novel insecticides, further studies on the safety of the essential oil to humans and on development of formulations are necessary to improve the efficacy and stability and to reduce costs.

Repellent Activity

The essential oil and isolated compounds showed stronger repellent activity against Li. bostrychophila than L. serricorne. At the concentration of 31.58 nl/cm2, the percentage repellency against Li. bostrychophila of the essential oil and isolated compounds were even higher than 90% at 2 and 4 h after exposed. So Li. bostrychophila was more sensitive to the essential oil and isolated compounds than L. serricorne. Moreover, it was found that the variety of the percentage repellency was obviously affected by the testing concentrations and the exposure duration. The percentage repellency of the essential oil and the two compounds increased with the increase of testing concentrations except that myristicin showed strongest repellent activity against Li. bostrychophila at the concentration of 6.32 nl/cm2. So the recommended concentration of the essential oil and p-cymene-8-ol against L. serricorne and Li. bostrychophila is 39.32 nl/cm2, whereas 39.32 nl/cm2 is the recommended concentration of myristicin against L. serricorne and 6.32 nl/cm2 is the recommended concentration of myristicin against Li. bostrychophila.

In this article, we reported the isolation of two insecticidal constituents from the essential oil of C. anisum-olens for the first time. The work indicates that the C. anisum-olens essential oil and its isolated constituents possess significant contact and repellent activities against two stored product insects. As rich in natural resources, C. anisum-olens essential oil and bioactive compounds have potential to apply in controlling stored product pests. However, for the practical application of the essential oil and the isolated constituents in real-world pest control, further studies on the safety, efficacy, and stability are necessary.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81374069), Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (7142093), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

References Cited

- Chen H. P., Yang K., You C. X., Lei N., Sun R. Q., Geng Z. F., Ma P., Cai Q., Du S. S., Deng Z. W. 2014. Chemical constituents and insecticidal activities of the essential oil of Cinnamomum camphora leaves against Lasioderma serricorne. J. Chem. 2014: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gurudutt K. N., Pasha M. A., Ravindranath B., Srinivas P. 1984. Reactions of oxiranes with alkali metals: intermediacy of radical-anions. Tetrahedron 40: 1629–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Institutum Botanicum Kunmingenge Academiae Sinicae. 2001. Flora Yunnanica (Spermatophyta), p. 767 (in Chinese). Science Press, Beijing, Tomus 6. [Google Scholar]

- Isman M. B. 2004. Plant essential oils as green pesticides for pest and disease management. ACB Symp. 887: 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Isman M. B. 2006. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51: 45–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H., Sung B. K., Lee H. S. 2006. Acaricidal activity of fennel seed oils and their main components against Tyrophagus putrescentiae, a stored-food mite. J. Stored Prod. Res. 42: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Q., Bai C. Q., Chu S. S., Zhou L., Du S. S., Liu Z. L., Liu Q. Z. 2011a. Chemical composition and toxicities of the essential oil derived from Kadsura heteroclite stems against Sitophilus zeamais and Meloidogyne incognita. J. Med. Plants Res. 5: 4943–4948. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. H., Kucerova Z., Zhao S., Stejskal V., Opit G., Qin M. 2011b. Morphological and molecular identification of three geographical populations of the storage pest Liposcelis bostrychophila (Psocoptera). J. Stored Prod. Res. 47: 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Li J. L., Xu S., Zhao N. N., Zhou L., Cheng J., Liu Z. L. 2013. Evaluation of repellency of some Chinese medicinal herbs essential oils against Liposcelis bostrychophila (Psocoptera: Liposcelidae) and Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 106: 513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. L., Ho S. H. 1999. Bioactivity of the essential oil extracted from Evodia rutaecarpa Hook f. et Thomas against the grain storage insects, Sitophilus zeamais Motsch. and Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) . J. Stored Prod. Res. 35: 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. L., Goh S. H., Ho S. H. 2007. Screening of Chinese medicinal herbs for bioactivity against Sitophilus zeamais Mostchulsky and Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). J. Stored Prod. Res. 43: 290–296. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. C., Li Y. P., Li H. Q., Deng Z. W., Zhou L., Liu Z., Du S. S. 2013a. Identification of repellent and insecticidal constituents of the essential oil of Artemisia rupestris L. aerial parts against Liposcelis bostrychophila Badonnel. Molecules 18: 10733–10746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. C., Zhou L. G., Liu Z. L., Du S. S. 2013b. Identification of insecticidal constituents of the essential oil of Acorus calamus Rhizomes against Liposcelis bostrychophila Badonnel. Molecules 18: 5684–5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahroof R. M. 2013. Stable isotopes and elements as biological markers to determine food resource use pattern by Lasioderma serricorne (Coleoptera: Anobiidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 52: 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Molino J. F. 2000. The inheritance of leaf oil composition in Clausena anisum-olens (Blanco) Merr. J. Essent. Oil Res. 12: 135–139 [Google Scholar]

- Nayak M. K., Daglishi G. J., Byrne V. S. 2005. Effectiveness of spinosad as a grain protectant against resistant beetle and psocid pests of stored grain in Australis. J. Stored Prod. Res. 41: 455–467. [Google Scholar]

- Passreiter C. M., Akhtar Y., Isman M. B. 2005. Insecticidal activity of the essential oil of Ligusticum mutellina roots. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C-a J. Biosci. 60: 411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui H. K., Ji W. L. 1992. The chemical constituents of essential oils from Illicium difengpi. Guihaia 12: 381–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma M. 1998. Probit analysis of preference data. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 33: 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q. H., Lv L., Li L., Zhao L., Zhang G. Q. 2011. Analysis of the essential oil from two varieties of Epimediums by GC-MS. J. Pharm. Pract. 29: 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- Su X. F., Liang Z. Y. 2011. Chemical constituents of essential oil of different organs from Clausena anisum-olens. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 17: 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Su X. F., Huang L. J., Feng P. Z. 2011. Chemical composition analysis and antimicrobial activity of volatile oil from the nutlets of Clausena anisum-olens. Food Sci. 32: 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Turner B. D. 1998. Psocids as a nuisance problem in the UK. Pestic Outlook 9: 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. L., Yang C. S., Da W. R. 1994. GC-MS analysis of essential from pericarps of Illicium difengpi K.I.B. et Kim. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 19: 422–423, 448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. S., He H. P., Yang J. H., Di Y. T., Hao X. J. 2008a. New monoterpenoid coumarins from Clausena anisum-olens. Molecules 13: 931–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. S., Huang R., Li L., Zhang H. B., Yang J. H. 2008b. O-terpenoidal coumarins from Clausena anisum-olens Merr. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 36: 801–803. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. S., He H. P., Yang J. H., Di Y. T., Tan N. H., Hao X. J. 2009a. Clausenain B, a phenylalanine-rich cyclic octapeptide from Clausena anisum-olens. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 20: 478–481. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. S., Xu H. Y., Wang D. X., Yang J. H. 2009b. A new o-terpenoidal coumarin from Clausena anisum-olens. Molecules 14: 771–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Hasegawa H., Yamataka H. 2011. Dynamic path bifurcation in the Beckmann reaction: support from kinetic analyses. J. Org. Chem. 76: 4652–4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Wang C. F., You C. X., Geng Z. F., Sun R. Q., Guo S. S., Du S. S., Liu Z. L., Deng Z. W. 2014. Bioactivity of essential oil of Litsea cubeba from China and its main compounds against two stored product insects. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 17: 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. S., Zhao N. N., Liu Q. Z., Liu Z. L., Du S. S., Zhou L., Deng Z. W. 2011. Repellent constituents of essential oil of Cymbopogon distans aerial parts against two stored-product insects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59: 9910–9915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. Y., Zhao N. N., Du S. S., Yang K., Wang C. F., Liu Z. L., Qiao Y. J. 2012. Insecticidal activity of the essential oil of Lonicera japonica flower buds and its main constituent compounds against two grain storage insects. J. Med. Plants Res. 6: 912–917. [Google Scholar]

- Zoubiri S., Baaliouamer A. 2011. Chemical composition and insecticidal properties of some aromatic herbs essential oils from Algeria. Food Chem. 129: 179–182. [Google Scholar]