Abstract

In the United States, histoplasmosis is generally thought to occur mainly in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, and the classic map of histoplasmosis distribution reflecting this is second nature to many U.S. physicians. With the advent of the HIV pandemic reports of patients with progressive disseminated histoplasmosis and AIDS came from regions of known endemicity, as well as from regions not thought to be endemic for histoplasmosis throughout the world. In addition, our expanding armamentarium of immunosuppressive medications and biologics has increased the diagnosis of histoplasmosis worldwide. While our knowledge of areas in which histoplasmosis is endemic has improved, it is still incomplete. Our contention is that physicians should consider histoplasmosis with the right constellations of symptoms in any febrile patient with immune suppression, regardless of geographic location or travel history.

Keywords: Histoplasmosis, progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, pulmonary fungal infections, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, immunosuppression, infectious diseases, emerging, travelers, biologic drugs, Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, H. capsulatum var. duboisii

Introduction

Histoplasmosis, in the United States, is primarily seen in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys1. The narrative regarding histoplasmosis is supported by solid epidemiologic evidence. By the mid-20th century a geographic clustering of patients with histoplasmosis was noted,2 and mapping of reactive histoplasmin skin tests was employed in patients with pulmonary calcifications on chest radiographs who did not react to tuberculin skin testing3. Edwards and colleagues constructed the now quite familiar map of histoplasmin skin reactivity among naval recruits4.

While the central United States seemed to have the greatest prevalence of Histoplasmosis capsulatum var. capsulatum, Brazil5, Argentina6, India7, and South Africa8 have all reported small case series, and Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii was thought to exist predominantly in West Africa. Additionally, sporadic cases have been reported from Central and South America, Oceania, northern sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe6. Histoplasmin skin test sensitivity analyses showed fairly high levels throughout Central America and parts of South America as well as Puerto Rico, Dominica, and Mexico in addition to the central United States with almost no skin test sensitivity in Europe, and scant information available from the rest of the world6. These skin test surveys appeared to support the idea that histoplasmosis exposure was infrequent in the rest of the world.

Over a number of years over which the authors have gained experience at multiple centers around the United States and Italy, it is extremely common for trainees at all stages to make assumptions about whether a diagnosis is even possible based on the geographical location alone. This review will focus on the truly global nature of histoplasmosis while acknowledging, the infection is certainly more common in certain areas, and that our current knowledge of endemicity is incomplete.

Pathogenesis and Immunity

The portal of entry for H. capsulatum is the lung, and following inhalation an area of pneumonitis develops. Neutrophils are unable to destroy the organism, although macrophages can ingest but cannot destroy the fungus9. Initially during the pre-immune phase, the fungus disseminates widely throughout the body9. Once T-cell mediated immunity develops, the entire process is arrested and recovery occurs9 – this allows for most infections to go un-noticed in persons without immune deficits. Primary infection by H. capsulatum is predominantly asymptomatic9; however, in patients exposed to a large infecting inoculum, symptomatic pulmonary infection is more common, and many patients require hospitalization10.

The degree to which infection is often sub-clinical is illustrated well by a 1964 outbreak in Mason City, Iowa. Of the estimated 6000, predominantly asymptomatic infections only 1 person developed progressive disseminated histoplasmosis and 87 persons developed acute pulmonary histoplasmosis11. This attack rate in the context of the estimated number of sub-clinical infections was possible because an outbreak two years prior allowed for serial skin testing.)

In patients with faulty T-cell mediated immunity this localized containment does not occur and progressive dissemination may take place, leading to clinical illness9. Faulty T-cell mediated immunity may be innate (e.g. Job syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome, etc.), caused by immunosuppressive medications, or may be caused by immunodeficiency states related to other diseases such as malignancy or HIV infection 9. Inadequate T-cell function allows progressive disseminated histoplasmosis due to reactivation of previous infection among patients with new immune compromise and has been particularly noted among immigrants from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa in non-endemic geographic locales in Europe12,13. Further evidence of the importance of T-cell function in controlling Histoplasma infection was provided in a recent retrospective analysis of ~1400 HIV-infected persons in French Guiana in which the authors found a hazard ratio for the development of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis of 47.2 in patients with CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of 0–50 cells/L, as compared to >500 cells/L, with an inverse relationship continuing between CD4 count and hazard ratio at higher CD4 counts14. Table 1 reviews the more typical clinical manifestations of H capsulatum infection as well as associated risk factors. Treatment varies by infection type1,15–18.

Table 1.

Major clinical manifestations of histoplasmosis and associated risk factors

| Manifestation | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis | Young age, exposure to a large inoculum of Histoplasma |

| Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis | Older age, chronic obstructive lung disease related to tobacco use |

| Mediastinal lymphadenitis, granuloma, fibrosis | Young age undefined inflammatory or immunologic factors in mediastinal fibrosis |

| Pericarditis or rheumatologic syndrome | Young age, immunocompetence, male sex and African American race in pericarditis and female sex in rheumatologic syndromes |

| Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis | Immunocompromising condition or medication, primary or acquired immunodeficiency, age < 1 or >55 years |

The table above notes major categories of histoplasmosis and risk factors associated with development of this type of disease related to histoplasmosis.

Global Histoplasmosis and the advent of AIDS

In 1983, several patients who had been diagnosed with AIDS and progressive disseminated histoplasmosis were reported19–23. While one report came from a known hyper-endemic area for histoplasmosis in Indiana22, other reports came from areas in the United States (Texas, Michigan,) where histoplasmosis was less common19,21, or had not been thought to be present (New York, Colorado)20,23. These reports rapidly increased across the United States in endemic and non-endemic areas alike24,25. In addition, patients from around the world were reported from areas where histoplasmosis had been rarely or never reported such as Trinidad26, Thailand27, and the Democratic Republic of Congo28. By 1990, Wheat and colleagues noted >100 cases of histoplasmosis in persons with AIDS,29 and although many came from Indiana, a sizeable minority were from areas outside of traditional endemic zones. Most of the reported symptomatic cases were patients with progressive disseminated histoplasmosis,29 as opposed to isolated pulmonary infections as had been the most common presentation in HIV-uninfected patients (when the infection did indeed lead to symptomatic clinical illness). In the decades since, numerous case series of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis associated with HIV infection have been reported around the globe in locations with few, if any, previous reported cases30.

The widespread reporting of patients with progressive disseminated histoplasmosis since the advent of AIDS helped to identify previously unrecognized endemic areas where a great number of sub-clinical infections must have occurred but were not previously recognized. Similarly, for known outbreaks of histoplasmosis (including those reported in persons with AIDS), likely many more, sub-clinical, infections occur.

Ideally, antiretroviral therapy (ART) is started before immunocompromised occurs in HIV-infected persons and reverses the immune defect, reducing the likelihood of development of histoplasmosis. The idea of prevention is supported by a 2001 case-control study in which patients were matched for CD4 count among other factors – patients on ART had less risk all for developing disseminated histoplasmosis, even at low CD4 counts31. Interestingly, there have been reports of otherwise untreated histoplasmosis in persons with AIDS improving with ART alone32. In many high-income countries guidelines recommend that all HIV-infected persons are started on ART regardless of CD4 count33, and so advanced immune suppression related to HIV infection and opportunistic infections such as histoplasmosis are less frequent in these countries. However in many parts of the world ART access is still not adequate and more cases of disseminated histoplasmosis are likely.

While AIDS illuminated many areas of hidden histoplasmosis endemicity, cases in areas not previously known to be endemic are still being reported and our knowledge regarding the distribution of histoplasmosis is expanding. With the incomplete nature of our understanding in mind, the reminder of the review will focus on the worldwide distribution of histoplasmosis and factors that might influence our understanding of histoplasmosis distribution in the future as HIV has done in the past and continues to do.

Global distribution of histoplasmosis

Our present knowledge of the worldwide distribution of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum relies most on the histoplasmin skin-test surveys with additional information coming from soil isolation of the fungus. Many of the pertinent studies were conducted in the 1950–70s6,34,35. Notably a summary of skin-test studies by Mochi and Edwards in 19526, highlighted that the “highest prevalence of histoplasmin sensitivity is found in east-central part of the USA, in southern Mexico, Central America and certain parts of South America. An isolated, low sensitivity area has been reported from South Africa6, and almost no histoplasmin sensitivity has been found in Europe, with the possible exception of Italy”6. Much of Asia and nearby nations were excluded from their “preliminary attempt” to map the geographical distribution of histoplasmosis due to the lack of any data from these areas6.

A review regarding soil isolation of H. capsulatum written in 1964 by Libero Ajello, added that in addition to well known endemic areas such as North America (USA, Mexico), Central (Panama) and South America (Brazil, French Guiana, Perù and Venezuela) a few countries in Africa (Congo, Tanzania-, and South Africa’s Guateng and Limpopo provinces), Asia (Malaysia) and the Caribbean (Trinidad)36 also housed H. capsulatum within their borders.

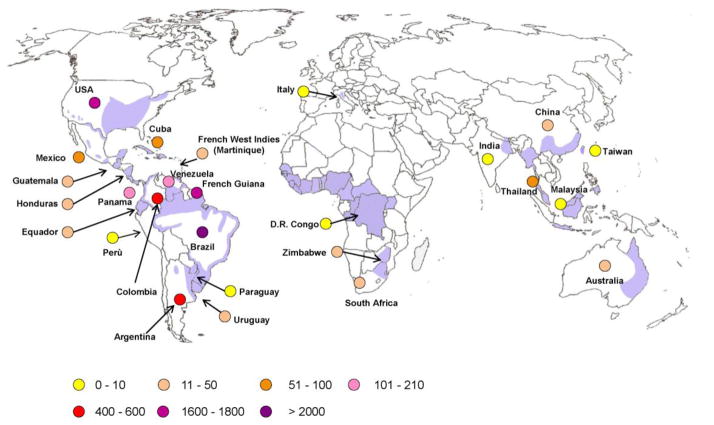

It is worth noting that until now the geopolitical isolation of several countries as well as the lack of microbiological facilities in many low-income areas of the world might have contributed to the difficulty in constructing an accurate map of worldwide histoplasmosis distribution. Table 2 shows studies from outside of the USA37–59, while Figure 1 shows a world map constructed with estimated areas endemic to histoplasmosis based on case reports primarily among HIV-infected patients.

Table 2.

Areas of endemicity for Histoplasma capsulatum outside United States of America (USA) according to histoplasmin skin reactivity

| Country/year/Reference | Number tested/Population | Histoplasmin skin test positivity % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

Asia

| ||

| China | ||

| Hunan province 200135 | 101 | 8.9 |

| Nanjing District 2001 | 292/healthy & pulmonary diseases | 16.8 |

| Sichuan province 199634 | 271 Healthy Students 28 TB patients |

6–35 |

|

| ||

| India 195533 | 962/NR | 1.9 |

| India (Delhi) 1962 | 8062/NR | 6.8 |

| India (Delhi riverine) 1960 | 162/NR | 12.3 |

| India (Calcutta) 1954 | 64/NR | 4.7 |

| India (Calcutta) 1956 | 4855/NR | 0.7 |

|

| ||

| Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur) 196433 | 227/Chest disease patients | 10.5 |

|

| ||

| Myanmar (Rangoon) 195233 | 1089/NR | 27.1 |

| Myanmar (Upper region) 1952 | 142/NR | 8.4 |

| Myanmar (Maguee) 1956 | 154/NR | 86.4 |

|

| ||

| Philippines (Manila) 1950–196433 | 3878/Navy recruits, TB patients, Medical & nurses students | 4.1–6.4 |

| Philippines (Luzon island) 200036 | 143/Healthy electric company employees | 26 |

|

| ||

| Taiwan (Nantou) 195633 | 444 | 49.8 |

|

| ||

| Thailand (Bangkok) 196733 | 497/Medical & nurses students | 5.6 |

| Thailand 1961 | 329/Student nurses | 4.0 |

| Thailand (Northern region) 1987 | NR/NR | 7–14 |

| Thailand (Central region) 1987 | NR/NR | 3–9 |

| Thailand (Southern region) 198739 | NR/NR | 15–36 |

|

| ||

| Vietnam (Saigon) 196033 | 303/NR | 33.7 |

|

| ||

| Central & South America | ||

|

| ||

| Argentina (Chaco province) 1996 | 315/Children | 9.2 |

|

| ||

| Brazil (Minas Gerais state) 199641 | 417/Miners | 17.5 |

| Brazil (Rio Grande Do Sul) 199643 | 354/Soldiers (17–19 years) | 48–89 |

| Brazil (Ceara State) 199242 | 138/Residents | 61.5 |

| Brazil (Amazonas state) 197844 | 495/Residents | 37.8 |

|

| ||

| Colombia (Department of Antioquia) 197145 | NR/National survey | 10 |

|

| ||

| Mexico (Guerrero state) 199749 | 139/Cave guides, peasants | 36.4–88.6 |

| Mexico (Guerrero,, Queretaro, Tlaxcala state) 199448 | 253/NR | 2 (Tlaxcala),83 (Guerrero),53 (Queretaro) |

|

| ||

| Venezuela (Bolivar state) 200546 | 182/Residents | 34 |

| Venezuela (Bolivar state) 200447 | 157/Farmers | 42.7 |

|

| ||

| Caribbean | ||

| Cuba (Ciego de Avila)199250 | 392/Poultry farmers | 28.8 |

| Barbados/198152 | NR | 4 |

| Trinidad/1981 | NR | 42 |

| Martinique & Guadeloupe 197253 | 454/Residents | 7 Martinique; 4 Guadeloupe |

|

| ||

| Africa | ||

|

| ||

| Nigeria 199151 | 1087-226/Healthy-hospital patients | 3.5 (Hcc):3.0 (Hcd) healthy |

| Nigeria (Anambra State) 199654 | 40/Cave guides, traders, farmers 620/Farmers, palm oil workers |

8.85 (Hcc);6.6 (Hcd) hospital pts 35 (Hcd) 8.8 (Hcd) |

|

| ||

| Somalia (Mogadishu & Jilib) 197955 | 1014/NR | 0.3 |

|

| ||

| Uganda (Gulu, Jinja, Amudat, Fort Portal and Kasese, Kampala, Pakwach) 197038 | 1144/residents | 0.4–12% |

Hcc, Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum; Hcd, Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii; NR, not reported

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum (purple) and H. capsulatum var. duboisii (shadow area).

The circles indicate the number of published cases of autochthonous AIDS-associated histoplasmosis (via Scopus query). The majority of African cases have been observed outside Africa

An important example of a country in which the increasing rate of infections has been recognized in recent years is China. A 2013 review found that from 1990 to 2011, 300 cases were reported in China of which 75% occurred along the Yangtze river60. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis occurred in 257 of the 300 cases and immune suppression, HIV in most cases, was present in most patients60. Studies from China report the prevalence of histoplasmin skin test reactivity ranging from 6% to 50%37–39. Interestingly the distribution of H. capsulatum overlaps that of Penicillium marneffei61 in several areas of China.

The occurrence of histoplasmosis in Asia has not been fully appreciated until recent years despite the fact that in 1970 Randhawa reviewed 30 autochthonous cases from India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and Japan37. Histoplasma has been isolated from the soil from these countries 62,63. Histoplasmin sensitivity was negligible in Japan, except in people working with soil and sand imported from overseas (including the USA)37, and H. capsulatum has never been isolated from the environment nor detected by PCR in bat guano from Japan 64.

In Thailand, the AIDS epidemic has been responsible of a dramatic upsurge of disseminated histoplasmosis with more than 1200 cases reported to the Ministry of Public Health from 1984 to 201065. A survey of histoplasmin sensitivity conducted in this country between 1966 and 1968 showed positivity rates of 7–14% in the northern region and 15–36% in the Southeast and Southern regions43, overlapping with areas containing Penicillium marneffei as determined by PCR 65.

Malaysia was the first country in Asia where H. capsulatum was successfully isolated from soil samples collected from bat-infested caves near Kuala Lumpur66, and a survey of histoplasmin skin test sensitivity showed a prevalence of 10.5% in that country37. Cases of histoplasmosis have been recognized both among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients as well as among subjects travelling to Malaysia67,68.

In India, histoplasmin sensitivity has been reported to be relatively high in Calcutta and Delhi (4.7–12.3%)37 with most cases occurring in north-eastern India in West Bengal and Assam states. Fungal isolation from soil has also occurred. An increasing number of cases of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis have been recognized in recent years in India among HIV-positive and/or diabetic patients, and some have suggested that histoplasmosis might be under-recognized due to being mistaken for tuberculosis69. In Australia, H. capsulatum has been cultured from different environmental sources (e.g. fowl yards and caves) in the States of Queensland and New South Wales. A recent review reported on 63 autochthonous cases from 1948 to 2009, including 11 with AIDS70.

In South and Central American large numbers of patients, many in persons infected with HIV, have been reported in Brazil, French Guiana, Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela and Panama (Figure 1) 14,71–74. Importantly, a recently published map of histoplasmosis endemic areas in the region did not include French Guiana75. This would seem to have been an oversight as progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is the most common cause of AIDS-defining illness in that country with one retrospective study finding that ~41% of HIV-positive hospitalized patients with fever and a CD4+ count < 200 cells/L had disseminated histoplasmosis14,71,72,76. Similarly, more than 70% of patients with histoplasmosis included in a survey conducted in Colombia from 1992 to 2008 had HIV/AIDS77. Argentina has an area of endemicity for histoplasmosis in the north-eastern part of the country78.

In Brazil, histoplasmosis is highly endemic especially in the northern (Amazona, Roraima, Parà, Amapà, Cearà, Rio Grande do Norte, Bahia), and mid-western states (Minas Gerais, Sao Paulo) as well as the south-eastern portions of the country. Histoplasmin positivity may be up to ~90% in some areas (although positivity varies widely by study, Table 2)36,45–48. Moreover, a recent study from 1996 to 2006 showed 4.73 per 1000 deaths associated with AIDS were due to histoplasmosis79.

A study conducted in metropolitan Caracas, Venezuela from 2000 to 2005 reported that AIDS was the risk factor in 33.5% of the 158 patients with histoplasmosis73. Histoplasmosis seems to be present in much of the region (Figure 1) with HIV playing a crucial role in symptomatic infections.

The distribution of histoplasmosis in Africa is probably the most puzzling due to the lack of solid epidemiologic studies coupled with the limited laboratory capacity available in much of the continent55,58,59,80,81. Complicating matters, there is the coexistence of two varieties of the fungus: H. capsulatum var. duboisii (“African histoplasmosis”) and H. capsulatum var. capsulatum on the continent. H capsulatum var. duboisii has been primarily noted in Nigeria, Niger, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda80–82 although a few cases have also been observed in Madagascar, Chad, Ivory Coast, Senegal83–86. Only 17 cases of H. capsulatum var. duboisii have been described among HIV-infected patients in Europe; with all being described as imported12. To the best of our knowledge only two studies, from Zimbabwe and South Africa, respectively, described 12 and 14 persons con-infected with AIDS and H. capsulatum var. capsulatum87,88. The majority of published cases of histoplasmosis caused by H. capsulatum var. capsulatum among HIV-infected Africans were observed in Europe as imported infections12,13,89. Although one study in Tanzania has identified patients with febrile illnesses that were likely due to histoplasmosis, the majority of patients tested were HIV-infected90. In this study, the testing was done retrospectively as Histoplasma antigen testing, the most sensitive method of diagnosis, is not available in the region90. Patients originated from Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Uganda, Central African Republic, Guinea Bissau, Senegal. In actuality, the majority of histoplasmosis cases in Africa are likely due to H. capsulatum var. capsulatum.

Travel, immigration, and histoplasmosis

The increasing number of persons travelling to endemic areas for tourism or international cooperation programs, or migrating for work is responsible of the growing number of reports of single or, more frequently, clusters of acute histoplasmosis. Numerous histoplasmosis cases among immigrants from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa have occurred. Of particular importance in these populations are the potential to reactivate a previous infection when starting on immune suppressive therapy12,13,89,91.

Table 3 shows cases related to international travel but not immigration91–106. Sleeping outdoors or spelunking (where bats are present) are associated with the development of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis among tourists. However in an outbreak, involving more than 200 US students in Acapulco, Mexico, which is the largest reported outbreak among travellers, the infection source was soil from a hotel’s ornamental potted plants that had been fertilized with compost94,107. More recently an outbreak with a high attack rate (61%) was observed among three mission groups that had travelled to El Salvador to renovate a church. Participation in dust-generating activities, such as digging or sweeping outdoors, were associated with an increased risk of symptomatic illness93. Although the number of reports of travel-associated histoplasmosis increased steadily in recent years (Table 3), likely many cases go unnoticed, especially if not presenting as a cluster of patients.

Table 3.

Reports of cluster of acute imported histoplasmosis among travelers from 1988 to 2013

| Author/year/Reference | N | Syndrome | Country of observation | Country of acquisition | Risk activity/ies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC, 198888 | 15 | Pulmonary | USA | Costa Rica | Visiting bat-cave |

| Nasta, 199794 | 4 | Pulmonary | Italy | Peru | Visiting bat-cave |

| Valdez, 199996 | 11 | Pulmonary | USA | Ecuador | Visiting bat-cave |

| Gascon, 200087 | 7 | Pulmonary | Spain | Santo Domingo (2); Perù; Guatemala (2); Nicaragua; Colombia | Visiting cave (Santo Domingo; Perù); sleeping in the forest (Nicaragua; Guatemala) |

| Buxton, 200297 | 14 | Pulmonary | Canada | Belize | Visiting cave |

| Salomon, 200398 | 13 | Pulmonary | France | Martinique (French West Indies) | Trekking (passage in a bat-infested tunnel) |

| Morgan, 200390 | 262 | Pulmonary | USA | Mexico | Stay in hotel with minor construction activities |

| Weinberg, 200391 | 5 | Pulmonary | USA | Nicaragua | Visiting bat-cave |

| Lyon, 200495 | 14 | Pulmonary | Usa | Costa Rica | Visiting bat-cave |

| Garcia-Vazquez, 200593 | 9 | Pulmonary | Spain | Guatemala | Renovation of an old school |

| Alonso, 200792 | 4 | Rheumatologic | Spain | Ecuador | Agricultural activity |

| CDC, 200889 | 20 | Pulmonary | USA | El Salvador | Construction activities (Church) |

| Norman, 2009102 | 5 | Pulmonary | Spain | Peru; El Salvador; Panama; Ecuador; multiple exposure (Costa Rica; French Guiana; Ecuador; Argentina) | Visiting bat-cave (3); entomologist (1); agricultural activity (1) |

| Buitrago, 201099 | 9 | Rheumatologic (4); pulmonary (3) | Spain | Ecuador (5); Nicaragua (1); Venezuela (1); Africa (2) | Visiting rural areas (4); visiting a cave (1); travelling to rural areas |

| Kajfastz, 2012101 | 4 | Pulmonary | Poland | Ecuador | Visiting bat-caves |

| Cottle, 2013100 | 13 | Pulmonary | UK | Uganda | Contact with bat-infested tree trunk |

Medical immunosuppression and histoplasmosis

The number of patients receiving immunosuppressive and cyto-reductive therapies are increasing, particularly among patients who receive biologic medications to treat rheumatologic, gastrointestinal or dermatologic diseases36,108–110. The fact that an intact immune system is important to prevent progressive dissemination of Histoplasma infection has been recognized9,14 and so these patients are more susceptible to histoplasmosis. For example, since as early as the 1950s, immune suppression in the form of Hodgkin’s lymphoma was recognized as a risk factor allowing for progressive disseminated histoplasmosis111.

Assi and colleagues conducted a large retrospective multi-center study of solid organ transplant patients with histoplasmosis in known endemic areas, reviewing 152 cases that occurred at 24 centers from 2003 to 2010110. Among 152 histoplasmosis infections, all patients were receiving immunosuppressive medications, most were receiving calcineurin inhibitors (138 of 152) and one or two other medications with mycophenolate preparations and corticosteroids being the most common110. Seventy eight patients had kidney transplantation, 24 had liver transplantation, 22 were pancreas/kidney transplant recipients, 14 received heart transplants, 8 lung transplants, and 3 received pancreas transplants while two other individual patients had kidney transplant combined with either heart or lung and one had a small bowel transplant110. In this population urine Histoplasma antigen was the most sensitive test detecting 132 of 142 cases and while the median time from transplant to diagnosis was 27 months, 34% of cases occurred in the first years after transplant110. Disseminated histoplasmosis occurred in 81% (122/152), and 10% (15/152) died110.

Patients with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis are also at risk for progressive disseminated histoplasmosis if immunosuppressive medications are used. In a single center study in an endemic area, 26 cases of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were infected with Histoplasma were summarized. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis was present in 46% (12/26) of patients with histoplasmosis109, 11 of the 12 patients were receiving multiple immune suppressive medications. Of the 26 total patients, 16 were receiving methotrexate, 15 were receiving tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors, 15 corticosteroids (mean dose 9.1mg/day), 5 hydroxychloroquine and 5 leflunomide109.

TNF-α inhibitors are particularly important as TNF-α is a key component of the granulomatous immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum108,112. As of 2010, 88 cases of histoplasmosis had been reported in patients using TNF-α inhibitors, a majority of cases were disseminated108. While many cases come from endemic areas, cases outside of endemic areas have been reported as well108. Cases continue to be reported, particularly in those patients using infliximab108. As an example, in Indiana, of 19 reported cases related to TNF-α inhibitor use, 13 patients were using infliximab108. A final note, paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is a worsening of symptoms after successful microbiologic treatment upon improving a weakened immune system. Just as IRIS can occur in HIV-infected persons upon starting ART113, IRIS can also occur when TNF-α inhibitors or other immunosuppressive medications are stopped108.

Conclusions

Histoplasmosis is a much more widespread than was once thought and current knowledge of its distribution is imcomplete30. The AIDS pandemic has elucidated a worldwide risk for histoplasmosis, including areas previously unknown to be endemic. While ART access has improved to the point that histoplasmosis in the setting of HIV infection is rare in high-income countries, histoplasmosis remains a significant cause of AIDS-associated mortality in many parts of the world. Additionally, increased international travel and use of immune suppressive medications are likely to lead to additional emergence of histoplasmosis infection from areas not previously known to be endemic, and the non-HIV-related incidence may continue to increase for progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. Thus, we believe histoplasmosis should be considered as a possible diagnosis in much of the world. Areas of higher density of exposure exist, and the consideration should be stronger if a patient has been to or lived in these locations. We advocate physicians considering disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with immune suppression, regardless of the location of the hospital to which the patient presents although the weight which one considers progressive disseminated histoplasmosis might vary widely depending on the patient’s location. Currently, Histoplasma antigen testing is not available in many areas not previously thought to be endemic, and this may limit one’s ability to diagnose the condition properly as it is currently the most sensitive method of diagnosis32,71,110. We look forward to the day when we no longer hear a presentation that includes, “well, they haven’t been to the Ohio River Valley so it can’t be histoplasmosis” from trainees.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Dr. Bahr is supported by National Institutes of Health Research Training Grant #R25TW009345 awarded by the Fogarty International Center, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, the National Institute of Mental Health, and Office of the Director as well as the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant #T32AI055433.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Nathan C Bahr, Spinello Antinori, L. Joseph Wheat and George A. Sarosi declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent:

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

* Of importance

** Of major importance

- 1.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807–825. doi: 10.1086/521259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuzma JF. Histoplasmosis; the pathologic and clinical findings. Dis Chest. 1947;13(4):338–344. doi: 10.1378/chest.13.4.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christie A. Histoplasmosis and pulmonary calcification; geographic distribution. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1951;31(6):742–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards LB, Acquaviva FA, Livesay VT, Cross FW, Palmer CE. An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, PPD-B, and histoplasmin in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1969;99(4 Suppl):1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Londero AT, Fischman O, Ramos C. A Critical Review of Medical Mycology in Brazil 1946–1960. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1962;18:293–316. doi: 10.1007/BF02051452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mochi A, Edwards PQ. Geographical distribution of histoplasmosis and histoplasmin sensitivity. Bull World Health Organ. 1952;5(3):259–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sethi KK, Passi S. Histoplasmosis in India. A critical review. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970;40(3):369–374. doi: 10.1007/BF02051792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klugman HB, Lurie HI. Systemic histoplasmosis in South Africa. A review of the previous cases and a report of an additional case--the first successfully treated. S Afr Med J. 1963;37:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knox KS, Hage CA. Histoplasmosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(3):169–172. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-069AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(12):1878–1882. doi: 10.1086/648421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medeiros AA, Marty SD, Tosh FE, Chin TD. Erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme as clinical manifestations of histoplasmosis in a community outbreak. N Engl J Med. 1966;274(8):415–420. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196602242740801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loulergue P, Bastides F, Baudouin V, et al. Literature review and case histories of Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii infections in HIV-infected patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(11):1647–1652. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.070665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antinori S, Magni C, Nebuloni M, et al. Histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected people in Europe: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(1):22–36. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000199934.38120.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Nacher M, Adenis A, Blanchet D, et al. Risk factors for disseminated histoplasmosis in a cohort of HIV-infected patients in French Guiana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(1):e2638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002638. This retrospective review convincingly shows an inverse risk of PDH with CD4+ T-cell count. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozols II, Wheat LJ. Erythema nodosum in an epidemic of histoplasmosis in Indianapolis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117(11):709–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthal J, Brandt KD, Wheat LJ, Slama TG. Rheumatologic manifestations of histoplasmosis in the recent Indianapolis epidemic. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(9):1065–1070. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(3):162–169. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheat LJ, Batteiger BE, Sathapatayavongs B. Histoplasma capsulatum infections of the central nervous system. A clinical review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69(4):244–260. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PG, Cohen RL, Batts DH, Silva J., Jr Disseminated histoplasmosis, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, and other opportunistic infections in a homosexual patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Sex Transm Dis. 1983;10(4):202–204. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198311000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur J, Myers AM. Homosexuality, steroid therapy, and histoplasmosis. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99(4):567. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-567_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasternak J, Bolivar R. Histoplasmosis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): diagnosis by bone marrow examination. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(10):2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sathapatayavongs B, Batteiger BE, Wheat J, Slama TG, Wass JL. Clinical and laboratory features of disseminated histoplasmosis during two large urban outbreaks. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62(5):263–270. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Small CB, Klein RS, Friedland GH, Moll B, Emeson EE, Spigland I. Community-acquired opportunistic infections and defective cellular immunity in heterosexual drug abusers and homosexual men. Am J Med. 1983;74(3):433–441. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90970-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wheat LJ, Slama TG, Zeckel ML. Histoplasmosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1985;78(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haggerty CM, Britton MC, Dorman JM, Marzoni FA., Jr Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis in suspected acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. West J Med. 1985;143(2):244–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartholomew C, Raju C, Patrick A, Penco F, Jankey N. AIDS on Trinidad. Lancet. 1984;1(8368):103. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vithayasai P, Vithayasai V. Clinical manifestations of 174 AIDS cases in Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital. J Dermatol. 1993;20(7):389–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1993.tb01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geffray L, Veyssier P, Cevallos R, et al. African histoplasmosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects, relation to AIDS. Apropos of 4 cases, including a case with HIV-1-HTLV-1 co-infection. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1994;145(6):424–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheat LJ, Connolly-Stringfield PA, Baker RL, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment, and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69(6):361–374. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antinori S. Histoplasma capsulatum: more widespread than previously thought. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(6):982–983. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajjeh RA, Pappas PG, Henderson H, et al. Multicenter case-control study of risk factors for histoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(8):1215–1220. doi: 10.1086/319756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myint T, Anderson AM, Sanchez A, et al. Histoplasmosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS): multicenter study of outcomes and factors associated with relapse. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2012 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2012;308(4):387–402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ajello L, Zeidberg LD. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum and Allescheria Boydii from soil. Science. 1951;113(2945):662–663. doi: 10.1126/science.113.2945.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emmons CW. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from soil. Public Health Rep. 1949;64(28):892–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajello L. Relationship of Histoplasma Capsulatum to Avian Habitats. Public Health Rep. 1964;79:266–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Randhawa HS. Occurrence of histoplasmosis in Asia. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970;41(1):75–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02051485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen FQ, Sun YD, Watanabe K, Yoshida M, Wu JN, Baum GL. Prevalence of histoplasmin sensitivity in healthy adults and tuberculosis patients in southwest China. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34(3):171–174. doi: 10.1080/02681219680000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao B, Xia X, Yin J, et al. Epidemiological investigation of Histoplasma capsulatum infection in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2001;114(7):743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulmer AC, Bulmer GS. Incidence of histoplasmin hypersensitivity in the Philippines. Mycopathologia. 2001;149(2):69–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1007277602576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CTH. Histoplasmin and coccidiodin sensitivity among students in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1953;4:549–554. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bezjak V, Farsey SJ. Prevalence of skin sensitivity to histoplasmin and coccidioidin in varous Ugandan populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19(4):664–669. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayanetra PPR, Satapathayawong B, Atichartrakarn V, Thianprasit M, Waropastrakul C, Poopaibul K, Kanjanasthiti P. The Magnitude of the Public Health Problem Posed by the Mycoses. Part II: The Lack of Information. J Infect Dis Antimicrob Agents. 1987;4:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mangiaterra M, Alonso J, Galvan M, Giusiano G, Gorodner J. Histoplasmin and paracoccidioidin skin reactivity in infantile population of northern Argentina (1) Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1996;38(5):349–353. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651996000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigues MT, de Resende MA. Epidemiologic skin test survey of sensitivity to paracoccidioidin, histoplasmin and sporotrichin among gold mine workers of Morro Velho Mining, Brazil. Mycopathologia. 1996;135(2):89–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00436457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diogenes MJ, Goncalves HM, Mapurunga AC, Alencar KF, Andrade FB, Nogueira-Queiroz JA. Histoplasmin and paracoccidioidin reactions in Serra de Pereiro. (Ceara State--Brazil) Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1990;32(2):116–120. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651990000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zembrzuski MM, Bassanesi MC, Wagner LC, Severo LC. An intradermal test with histoplasmin and paracoccidioidin in 2 regions of Rio Grande do Sul. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1996;29(1):1–3. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86821996000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mok WY, Netto CF. Paracoccidioidin and histoplasmin sensitivity in Coari (state of Amazonas), Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27(4):808–814. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carmona J. Analisis estadistico y ecologico-epidemiologico de la sensibilidad a la histoplasmina en Colombia 1950–1968. Antioquia Med. 1971;21:109–154. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cermeno JR, Cermeno JJ, Hernandez I, et al. Histoplasmine and paracoccidiodine epidemiological study in Upata, Bolivar state, Venezuela. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(3):216–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cermeno JR, Hernandez I, Cermeno JJ, et al. Epidemiological survey of histoplasmine and paracoccidioidine skin reactivity in an agricultural area in Bolivar state, Venezuela. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(2):189–193. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000017716.95609.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pedroza-Seres M, Quiroz-Mercado H, Granados J, Taylor ML. The syndrome of presumed ocular histoplasmosis in Mexico: a preliminary study. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(2):83–92. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor ML, Perez-Mejia A, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Granados J. Immunologic, genetic and social human risk factors associated to histoplasmosis: studies in the State of Guerrero, Mexico. Mycopathologia. 1997;138(3):137–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1006847630347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suarez Fernandez MFA, CM, Estrada Ortiz A, Cisneiros Despaigne E. Reactividad a la histoplasmina en trabajadores de granajas avicolas en la provincia de Ciego de Avila, Cuba. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1992;34:329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gugnani HC, Egere JU, Larsh H. Skin sensitivity to capsulatum and duboisii histoplasmins in Nigeria. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;94(1):24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hay RJ, White HS, Fields PE, Quamina DB, Dan M, Jones TR. Histoplasmosis in the eastern Caribbean: a preliminary survey of the incidence of the infection. J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;84(1):9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lambert de Cremeur Y, Drouhet E. Aspects of histoplasmosis in French possessions in the Americas. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1972;65(4):499–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muotoe-Okafor FA, Gugnani HC, Gugnani A. Skin and serum reactivity among humans to histoplasmin in the vicinity of a natural focus of Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii. Mycopathologia. 1996;134(2):71–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00436867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nuti M, Tarabini GC, Adorisio E, Zardi O. Histoplasmosis diffusion in Somalia: study of skin-test and serological survey. Biochem Exp Biol. 1979;15(2):111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60**.Pan B, Chen M, Pan W, Liao W. Histoplasmosis: a new endemic fungal infection in China? Review and analysis of cases. Mycoses. 2013;56(3):212–221. doi: 10.1111/myc.12029. This large review analyzed 300 cases of histoplasmosis in China over the preceding 30 years, most cases were PDH and most were related to advanced HIV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan B, Deng S, Liao W, Pan W. Endemic mycoses: overlooked diseases in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(10):1516–1517. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chakrabarti A, Slavin MA. Endemic fungal infections in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol. 2011;49(4):337–344. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.551426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang TL, Cheah JS, Holmberg K. Case report and review of disseminated histoplasmosis in South-East Asia: clinical and epidemiological implications. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1(1):35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kikuchi K, Sugita T, Makimura K, et al. Is Histoplasma capsulatum a native inhabitant of Japan? Microbiol Immunol. 2008;52(9):455–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Norkaew T, Ohno H, Sriburee P, et al. Detection of environmental sources of Histoplasma capsulatum in Chiang Mai, Thailand, by nested PCR. Mycopathologia. 2013;176(5–6):395–402. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9701-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ponnampalam J. Isolation of Histoplasma Capsulatum from the Soil of a Cave in Central Malaya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1963;12:775–776. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1963.12.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jing W, Ismail R. Mucocutaneous manifestations of HIV infection: a retrospective analysis of 145 cases in a Chinese population in Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(6):457–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ohno H, Ogata Y, Suguro H, et al. An outbreak of histoplasmosis among healthy young Japanese women after traveling to Southeast Asia. Intern Med. 2010;49(5):491–495. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gopalakrishnan R, Nambi PS, Ramasubramanian V, Abdul Ghafur K, Parameswaran A. Histoplasmosis in India: truly uncommon or uncommonly recognised? J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McLeod DS, Mortimer RH, Perry-Keene DA, et al. Histoplasmosis in Australia: report of 16 cases and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90(1):61–68. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318206e499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Couppie P, Aznar C, Carme B, Nacher M. American histoplasmosis in developing countries with a special focus on patients with HIV: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19(5):443–449. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000244049.15888.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huber F, Nacher M, Aznar C, et al. AIDS-related Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum infection: 25 years experience of French Guiana. AIDS. 2008;22(9):1047–1053. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ffde67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mata-Essayag S, Colella MT, Rosello A, et al. Histoplasmosis: a study of 158 cases in Venezuela, 2000–2005. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87(4):193–202. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31817fa2a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nacher M, Adenis A, Mc Donald S, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients in South America: a neglected killer continues on its rampage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(11):e2319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colombo AL, Tobon A, Restrepo A, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med Mycol. 2011;49(8):785–798. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.577821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76**.Vantilcke V, Boukhari R, Jolivet A, et al. Fever in hospitalized HIV-infected patients in Western French Guiana: first think histoplasmosis. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(9):656–661. doi: 10.1177/0956462413516299. This retrospective study analyzed HIV infected patients hospitalized with a febrile illness. The findings of the study are striking in that while 41% of these patients with CD4+ cell counts <200 had PDH, over 85% of those patients with CD4+ cell counts<50 had PDH. This is an incredibly important finding for this region. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arango M, Castaneda E, Agudelo CI, et al. Histoplasmosis: results of the Colombian national survey, 1992–2008. Biomedica. 2011;31(3):344–356. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572011000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Corti MENR, Esquivel P, Villafane MF. Histoplasmosis diseminada en paziente con SIDA: analisis epidemiologico, clinico, microbiologico e inmunologico de 26 pacientes. Enf Emerg. 2004;6:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prado M, Silva MB, Laurenti R, Travassos LR, Taborda CP. Mortality due to systemic mycoses as a primary cause of death or in association with AIDS in Brazil: a review from 1996 to 2006. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(3):513–521. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gugnani HC, Muotoe-Okafor F. African histoplasmosis: a review. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14(4):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams AO, Lawson EA, Lucas AO. African histoplasmosis due to Histoplasma duboisii. Arch Pathol. 1971;92(5):306–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khalil MA, Hassan AW, Gugnani HC. African histoplasmosis: report of four cases from north-eastern Nigeria. Mycoses. 1998;41(7–8):293–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coulanges P. Large-form histoplasmosis (H. duboisii) in Madagascar (apropos of 3 cases) Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1989;56(1):169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coulanges P, Raveloarison G, Ravisse P. Existence of Histoplasma duboisii histoplasmosis outside continental Africa (apropos of the first Madagascar case) Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1982;75(4):400–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Garcia-Guinon A, Torres-Rodriguez JM, Ndidongarte DT, Cortadellas F, Labrin L. Disseminated histoplasmosis by Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii in a paediatric patient from the Chad Republic, Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28(6):697–699. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oddo D, Etchart M, Thompson L. Histoplasmosis duboisii (African histoplasmosis). An African case reported from Chile with ultrastructural study. Pathol Res Pract. 1990;186(4):514–517. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80473-5. discussion 518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gumbo T, Just-Nubling G, Robertson V, Latif AS, Borok MZ, Hohle R. Clinicopathological features of cutaneous histoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Zimbabwe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95(6):635–636. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.PKR, Mosam A, Dlova NC, NBS, Aboobaker J, Singh SM. Disseminated cutaneous histoplasmosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29(4):215–225. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Inojosa W, Rossi MC, Laurino L, et al. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients from West-Africa: report of four imported cases in Italy. Infez Med. 2011;19(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lofgren SM, Kirsch EJ, Maro VP, et al. Histoplasmosis among hospitalized febrile patients in northern Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(8):504–507. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gascon J, Torres JM, Luburich P, Ayuso JR, Xaubet A, Corachan M. Imported histoplasmosis in Spain. J Travel Med. 2000;7(2):89–91. doi: 10.2310/7060.2000.00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Centers for Disease C. Cave-associated histoplasmosis--Costa Rica. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37(20):312–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Centers for Disease C and Prevention. Outbreak of histoplasmosis among travelers returning from El Salvador--Pennsylvania and Virginia, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(50):1349–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morgan J, Cano MV, Feikin DR, et al. A large outbreak of histoplasmosis among American travelers associated with a hotel in Acapulco, Mexico, spring 2001. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69(6):663–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weinberg M, Weeks J, Lance-Parker S, et al. Severe histoplasmosis in travelers to Nicaragua. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(10):1322–1325. doi: 10.3201/eid0910.030049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alonso D, Munoz J, Letang E, et al. Imported acute histoplasmosis with rheumatologic manifestations in Spanish travelers. J Travel Med. 2007;14(5):338–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garcia-Vazquez E, Velasco M, Gascon J, Corachan M, Mejias T, Torres-Rodriguez JM. Histoplasma capsulatum infection in a group of travelers to Guatemala. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2005;23(5):274–276. doi: 10.1157/13074968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nasta P, Donisi A, Cattane A, Chiodera A, Casari S. Acute Histoplasmosis in Spelunkers Returning from Mato Grosso, Peru. J Travel Med. 1997;4(4):176–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1997.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lyon GM, Bravo AV, Espino A, et al. Histoplasmosis associated with exploring a bat-inhabited cave in Costa Rica, 1998–1999. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70(4):438–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Valdez H, Salata RA. Bat-associated histoplasmosis in returning travelers: case presentation and description of a cluster. J Travel Med. 1999;6(4):258–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1999.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Buxton JA, Dawar M, Wheat LJ, et al. Outbreak of histoplasmosis in a school party that visited a cave in Belize: role of antigen testing in diagnosis. J Travel Med. 2002;9(1):48–50. doi: 10.2310/7060.2002.22444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Salomon J, Flament Saillour M, De Truchis P, et al. An outbreak of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in members of a trekking trip in Martinique, French West Indies. J Travel Med. 2003;10(2):87–93. doi: 10.2310/7060.2003.31755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buitrago MJ, Bernal-Martinez L, Castelli MV, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. Histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis in a non-endemic area: a review of cases and diagnosis. J Travel Med. 2011;18(1):26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cottle LE, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Williams HJ, et al. A multinational outbreak of histoplasmosis following a biology field trip in the Ugandan rainforest. J Travel Med. 2013;20(2):83–87. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kajfasz P, Basiak W. Outbreak of pulmonary histoplasmosis involving a group of four Polish travellers returning from Ecuador. Int Marit Health. 2012;63(1):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Norman FF, Martin-Davila P, Fortun J, et al. Imported histoplasmosis: two distinct profiles in travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med. 2009;16(4):258–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taylor ML, Ruiz-Palacios GM, del Rocio Reyes-Montes M, et al. Identification of the infectious source of an unusual outbreak of histoplasmosis, in a hotel in Acapulco, state of Guerrero, Mexico. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;45(3):435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108*.Hage CA, Bowyer S, Tarvin SE, Helper D, Kleiman MB, Wheat LJ. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(1):85–92. doi: 10.1086/648724. This study reviewed a relatively large number of cases of histoplasmosis associated with TNF-α inhibitor use, the majority of which were PDH. In addition, the study brings out the importance of considering immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome with removal of the offending immunosuppressive agent. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109*.Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-145. This single center study make two important points. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are at risk of histoplasmosis even if on minimal or no immune suppression; however, if a patient with rheumatoid arthritis is on immune supressive therapy, the likelyhood of the infection progressing to PDH is much higher. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110*.Assi M, Martin S, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis after solid organ transplant. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(11):1542–1549. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit593. This large retrospective multi-center study of solid organ transplant patients with histoplasmosis. The study encompassed 152 infections at 24 centers and characterized transplant type, immune suppression used, the type of infection as well as mortality in this population. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ende N, Pizzolato P, Ziskind J. Hodgkin’s disease associated with histoplasmosis. Cancer. 1952;5(4):763–769. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195207)5:4<763::aid-cncr2820050417>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Deepe GS, Jr, Wuthrich M, Klein BS. Progress in vaccination for histoplasmosis and blastomycosis: coping with cellular immunity. Med Mycol. 2005;43(5):381–389. doi: 10.1080/13693780500245875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Marianelli LG, Frassone N, Marino M, Debes J. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome as histoplasmosis osteomyelitis in South America. AIDS. 2014;28(12):1848–1850. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]