Abstract

Many East Asians experience lower eyelid bulging and discoloration, and this is seen even in young individuals. The condition is caused by an undergrowth of the maxilla and not by aging. In this condition, the orbit appears small and the infraorbital rim is hypoplastic. This inevitably causes a depressed, tired, and sad appearance. Here, the authors present techniques of volume augmentation in the lower eyelid and cheek areas to rejuvenate the midface in Asians.

Keywords: lower eyelid, midface, cheek, maxilla

Cephalic indices of Caucasians and Asians are different, such as dolichocephaly and mesocephaly, and midfacial growth and aging are likely to be different based on the skull base. Midface hypoplasia is a common variant of normal anatomy in Asians, which results in a concave midface profile. This skeletal feature may combine with soft tissue features such as ptosis and atrophy in midfacial aging.1 Additionally, skeletal remodeling occurs because the nature of contiguous surfaces differ.2

In Westerners, midfacial aging tends to occur around the lower maxillary pyriform skeleton to become retrusive; this contributes to a prominent nasolabial fold at an early age.3 However, according to our previous computed tomography- (CT-) based study (data not published), Asians show reduction of the lengths of the orbital roof and floor with aging relative to a decrease in the maxillary angle, and this is the leading cause of prominent tear trough deformities and dark circles in young Asians. Here we present techniques of volume augmentation in the lower eyelid and cheek areas to rejuvenate the midface in Asians.

Differences in Midfacial Aging between Westerners and Asians

According to Pessa et al,1 the inferior orbital rim and the anterior maxilla serve as key foundations for the soft tissues of the inferior orbit and midface. However, both these structures retrude with advancing age compared with the upper third of the facial skeleton. The anterior maxillary wall retrudes in relation to the bony orbit, which is indicated by a decrease in the angle between the maxilla and orbital floor. This retrusion mainly occurs at a point below the nasolabial fold, and the malar fat easily moves downward compared with infraorbital fat herniation with aging in Westerners. Therefore, in Westerners, there are more recommendations for fat removal or septal fat reset than for volume addition in the inferior orbital rim area (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Midfacial aging in Westerners.

In East Asians, the mesocephalic shape of the skull inevitably induces mild to moderate maxillary retrusion; this is seen even in young individuals. In this condition, the inferior orbital rim becomes a negative vector. In our previous CT-based study, we found that bony atrophy in the inferior orbital rim accelerates with aging (data not shown). However, changes in the maxillary angle are not significant, and this is related to the descent of a low amount of malar and jowl fat. Therefore, in Asians, volume addition to the inferior orbital rim is necessary to rejuvenate the midface, and this can be used even in young individuals who appear older than their actual age (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Midfacial aging in Asians.

Treatment

In young individuals, the eyelid-cheek complex has a smooth convex profile. However, aging causes descent of the globe in the orbit and pseudoherniation of intraorbital fat, producing a double convex or tear trough deformity and a nasojugal groove at the medial aspect of the lower eyelid.4 This condition can worsen if there is not enough structural support. In our previous CT-based study, we found that atrophy of the inferior orbital rim is greater in Asians than in Westerners. We present the following three potential techniques to reinforce this area.

Septal Fat Repositioning

We recommend this procedure to individuals with a neutral or positive vector relationship of the orbit and inferior orbital rim, and with mild to moderate pseudoherniation of fat. The procedure can be performed via the transcutaneous or transconjunctival approach, depending on cutaneous redundancy. In young individuals, the transconjunctival approach is preferred as it avoids violation of the anterior lamellar, which may produce less postoperative eyelid retraction. The basic surgical technique includes release of the arcus marginalis and advancement of the septal fat beyond the infraorbital rim and underneath the orbicularis muscle. The fat pedicles are externalized to the midface by suturing to a relatively rigid adjacent soft tissue, using 7–0 nylon stitches. They can be placed in the subperiosteal or supraperiosteal planes, but the supraperiosteal plane is preferred. In individuals with a deep tear trough deformity, the orbital retaining ligament and medial orbicularis oculi attachments may be released easily using this approach. Additionally, microinstruments can be effectively used in a small visual field without canthotomy procedures. This technique results in leveling of the tear trough deformity, a smooth contour of the lower eyelid, and high patient satisfaction (Fig. 3).

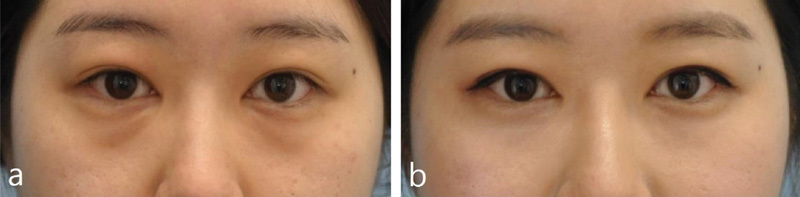

Fig. 3.

Images of a 26-year-old woman who underwent transconjunctival septal fat repositioning. (A) Preoperative image. (B) Postoperative image 1 year after the procedure. Fat herniation and tear trough deformity is relieved after the procedure.

Fat Grafting

Fat grafting is a very important technique used by aesthetic plastic surgeons to recover reduced bony and soft tissue volume caused by aging. However, when performing procedures on a face, it is important not to injure any nerves or normal structures of mimetic muscles. We have been performing muscle unit fat grafting via the intraoral approach since 2007. This procedure causes low swelling and bruising, and allows easy access for dual plane insertion in the submuscular and supramuscular planes.

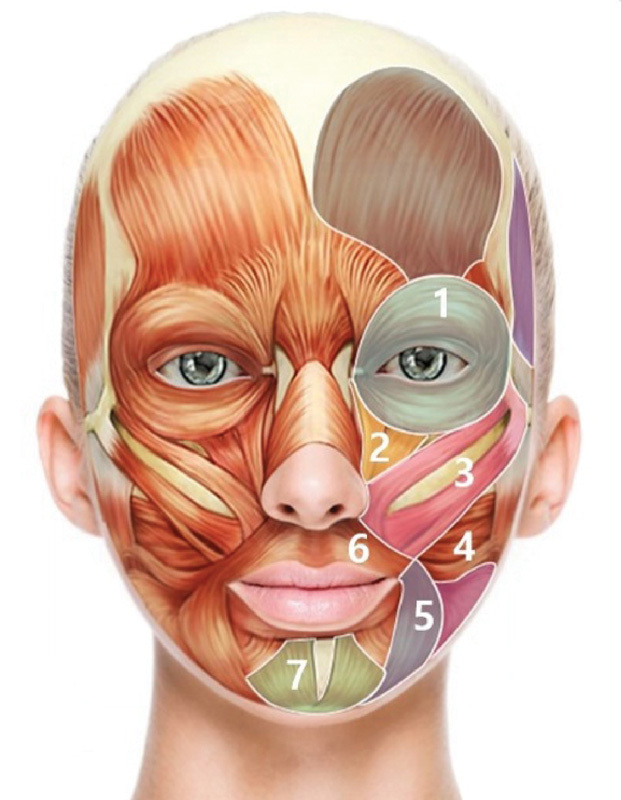

Gierloff et al recently published a study on the presence of superficial and deep plane facial fat compartments detected on CT.5 Based on their findings, we perform dual plane fat grafting in each muscle unit using the intraoral approach. Additionally, fat compartments are classified according to muscle units; therefore, it is logical to divide facial units according to muscle groups. Fat acts as a gliding plane for the muscles, and provides support for the muscles. The classification of facial units should be performed with functionally important and rigidly fixed units, and not with floating variant units. Fig. 4 presents the classification of facial fat compartments according to muscle units.

Fig. 4.

Facial fat compartments are classified according to muscle units. 1. Orbicularis unit; 2. levator labii superior unit; 3. zygomaticus unit; 4. risorius unit; 5. depressor anguli unit; 6. orbicularis oris unit; 7. mentalis unit. Each unit has dual fat planes, which are superficial and deep to muscles.

We frequently question the chances of infection in this approach. However, surprisingly, we experienced only one case of infection, and the individual had a history of foreign body injection in both the cheeks. When using the gingivobuccal approach for bone surgeries, infection is rare. With proper oral hygiene, a small entry portal, the mucous membrane for cannula insertion, rarely causes any issues.

This approach is ideally performed in individuals with midfacial lipoatrophy, malar bony retrusion, and mild-to-moderate ectropion induced by weak infraorbital support (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Images of a 29-year-old woman with a flat midface who underwent fat grafting. (A–C) Preoperative images. (D–F) Postoperative images 2 years after the procedure. Fat compartments in the muscle units are well maintained.

Custom Silicone Implantation

Custom silicone implants can be a good option for individuals of all ages. These implants will successfully correct infraorbital and midfacial retrusion provided they are securely fixed at the location of skeletal deficiencies.

Individuals who do not want temporary or unpredictable results can consider silicone implants. We have been developing better ready-to-use methods for increasing the applicability of custom facial implants in aesthetic surgery since 2009.

First, a cone beam CT (CBCT) is used to identify the problem and obtain images of the anatomical target sites. Cone beam CT is advantageous, as it requires lesser space, uses a lower radiation dose, has a lower cost, and produces higher resolution images compared with those for conventional CT. Second, a surface tessellation language file is generated from CBCT scans using a computer. This allows the production of an accurate rapid prototype (RP) model. Third, custom implants are produced based on the RP model, using polyvinyl alcohol clay to mold the shape of the implants. This process is advantageous as it requires a minimal mixing and drying time. Finally, the silicone implants are used. They have a low rate of infection and can be replaced and shaped easily. With this technique, excellent outcomes can be obtained in individuals who desire permanent predictable results. If complications such as foreign body reaction and infection occur, the implants can be easily removed, and the capsular space can be filled with autologous fat or bone (Fig. 6).6

Fig. 6.

Frontal images of an 82-year-old man with lower eyelid palpebral bags, who underwent custom silicone implantation via the transcutaneous approach. (A) A preoperative image demonstrating typical double convexity of the eyelid and periorbital aging. Eyelid fat herniation, lid–cheek interface depression with an unmasked orbital rim, and midface convexity are seen. (B) A postoperative image 3 months after the procedure. (C) An image showing the underlying skeleton and custom implant insertion in the inferior orbital rim.

Conclusion

A complete understanding of the facial anatomy differences between Asians and Westerners can help diversify the techniques used for facial surgery and can help select techniques according to each case. Septal fat reposition, fat grafting, and custom silicone implantation can be effectively performed in all adult Asians Surgeons should evaluate the benefits and limitations of each technique, and continue to develop and introduce new techniques for facial surgery.

Footnotes

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Pessa J E, Zadoo V P, Mutimer K L. et al. Relative maxillary retrusion as a natural consequence of aging: combining skeletal and soft-tissue changes into an integrated model of midfacial aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(1):205–212. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199807000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enlow D H, Hunter W S. The growth of the face in relation to the cranial base. Rep Congr Eur Orthod Soc. 1968;44:321–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendelson B C, Hartley W, Scott M, McNab A, Granzow J W. Age-related changes of the orbit and midcheek and the implications for facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31(5):419–423. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamra S T. Arcus marginalis release and orbital fat preservation in midface rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(2):354–362. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199508000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gierloff M, Stöhring C, Buder T, Gassling V, Açil Y, Wiltfang J. Aging changes of the midfacial fat compartments: a computed tomographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(1):263–273. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182362b96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett S P, Grossman R, Whitaker L A. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: an anthropometric and histologic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90(4):592–600. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]