Abstract

The insulin-like peptides (ILPs) and their respective signaling and regulatory pathways are highly conserved across phyla. In invertebrates, ILPs regulate diverse physiological processes, including metabolism, reproduction, behavior, and immunity. We previously reported that blood feeding alone induced minimal changes in ILP expression in Anopheles stephensi. However, ingestion of a blood meal containing human insulin or Plasmodium falciparum, which can mimic insulin signaling, leads to significant increases in ILP expression in the head and midgut, suggesting a potential role for AsILPs in the regulation of P. falciparum sporogonic development. Here, we show that soluble P. falciparum products, but not LPS or zymosan, directly induced AsILP expression in immortalized A. stephensi cells in vitro. Further, AsILP expression is dependent on signaling by the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK/ERK) and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K)/Akt branches of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) pathway. Inhibition of P. falciparum-induced ILPs in vivo decreased parasite development through kinetically distinct effects on mosquito innate immune responses. Specifically, knockdown of AsILP4 induced early expression of immune effector genes (1–6 hours after infection), a pattern associated with significantly reduced parasite abundance prior to invasion of the midgut epithelium. In contrast, knockdown of AsILP3 increased later expression of the same genes (24 hours after infection), a pattern that was associated with significantly reduced oocyst development. These data suggest that P. falciparum parasites alter the expression of mosquito AsILPs to dampen the immune response and facilitate their development in the mosquito vector.

Keywords: Mosquito, Anopheles, immunity, insulin, insulin-like peptide, malaria, Plasmodium, NF-κB

1. Introduction

The human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, is transmitted by mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles and causes over 500,000 deaths annually (WHO, 2014). Transmission of Plasmodium parasites requires ingestion of an infectious blood meal by a mosquito. In the mosquito midgut, ingested Plasmodium gametocytes undergo a series of developmental changes in the context of robust immune responses that contribute to marked losses in parasite numbers (Clayton et al., 2014; Yassine et al., 2010). This process is regulated in part by insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (Corby-Harris et al., 2010; Drexler et al., 2013; Drexler et al., 2014; Hauck et al., 2013; Horton et al., 2010; Luckhart et al., 2013; Pakpour et al., 2012; Surachetpong et al., 2009; Surachetpong et al., 2010).

The regulation and function of IIS are highly conserved among vertebrate and invertebrate species (Luckhart & Riehle, 2007; Wu & Brown, 2006). In mammals, insulin biosynthesis is regulated by autocrine positive feedback that controls both insulin gene transcription and peptide secretion through activation of IIS proteins (Khoo et al., 2003; Leibiger et al., 1998; Leibiger et al., 2000; Melloul et al., 2002). Following secretion, insulin and two insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) can signal through receptor tyrosine kinase homodimers to regulate a variety of physiological processes. Additionally, mammals utilize seven other relaxin family insulin-like peptides (ILPs) that signal through G-protein coupled receptors (Halls et al., 2007). Varied numbers of ILPs have been identified in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Brogiolo et al., 2001), the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Duret et al., 1998), the silkmoth Bombyx mori (Mizoguchi & Okamoto, 2013), as well as the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti (Riehle et al., 2006), Anopheles gambiae (Krieger et al., 2004), and Anopheles stephensi (Marquez et al., 2011). Invertebrate ILPs regulate behavior (Nassel, 2012), metabolism (Broughton et al., 2008; Gulia-Nuss et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2009), reproduction (Brown et al., 2008; Gulia-Nuss et al., 2011; Sim & Denlinger, 2009), aging (Evans et al., 2008, Broughton et al., 2010) and immunity (Evans et al., 2008; Garsin et al., 2003).

In A. stephensi, ILP expression does not change significantly with age or upon ingestion of a sugar or blood meal. However, ingestion of a P. falciparum-infected blood meal profoundly increased expression of AsILP2, 3, 4, and 5 in the head and midgut (Marquez et al., 2011). In support of a role for AsILPs in parasite infection, studies of field-collected A. gambiae from Mali identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in AgILP3 that was significantly associated with natural P. falciparum infection (Horton et al., 2010). We have since identified additional infection-associated SNPs in AgILP3 and AgILP4 that are predicted to alter protein function (unpublished data). These observations provide further evidence that mosquito ILPs – and likely Anopheles ILP3 and 4, in particular – contribute to the regulation of parasite development.

Strong mechanistic links between IIS and immunity have been well documented in other invertebrate species and these observations suggest that IIS and immune signaling are inversely correlated (Demas et al., 2011). That is, immune activation inhibits IIS, perhaps to allocate resources from storage and growth to the immune response, while up- and down-regulated IIS can inhibit or activate immunity to protect the host during infection and non-pathological physiological conditions, respectively. For example, activation of Toll signaling in D. melanogaster reduces endogenous IIS, leading to decreased nutrient storage during infection (DiAngelo et al., 2009). Similarly, Mycobacterium marinum infection-induced activation of Toll and IMD signaling in D. melanogaster resulted in a loss of metabolic stores (Dionne et al., 2006). In contrast, virulence factor-mediated increases in IIS during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in C. elegans suppressed anti-microbial peptide (AMP) gene expression, increasing bacterial colonization (Evans et al., 2008), while insulin receptor daf-2 mutants were resistant to bacterial pathogens (Garsin et al., 2003). In more recent studies, pathogen resistance in C. elegans was observed to occur independently of the DAF-2 pathway, resulting instead from direct pathogen activation of the IIS downstream target DAF-16, a forkhead box O (FOXO) transcripton factor (Zou et al., 2013). Our own studies affirmed that PI3K/Akt signaling is responsible for human insulin-induced repression of the innate immune responses of A. stephensi to P. falciparum infection (Pakpour et al., 2012), demonstrating that mosquito IIS regulates innate immune responses in a manner similar to that observed in D. melanogaster and C. elegans. However, little is known regarding the extent to which endogenous mosquito ILPs regulate host immunity.

Here, we build upon our previous studies demonstrating that P. falciparum infection can induce AsILP expression in the midgut to determine the mechanism and significance of this phenomenon (Marquez et al., 2011). Our results indicate that AsILP gene expression during P. falciparum infection results from parasite stimulation of IIS and not from immune activation by microbial signals that induce Toll/Immune deficiency (IMD) pathways. Induced AsILP3 and 4 cooperate temporally to facilitate parasite development in the mosquito by dampening NF-κB-mediated immune responses. Parasite-induced activation of IIS, therefore, suggests that P. falciparum has co-opted AsILP function in part for immune suppression in the mosquito host. Further, AsILP-dependent suppression of anti-parasite defenses extends our understanding of the regulation of immunity by IIS to include the activity of functionally distinct neuropeptides.

2. Results

2.1 Soluble P. falciparum products (PfPs) induced the transcription of AsILPs

We previously showed that expression levels of AsILP2, 3, 4 and 5 are induced in the mosquito midgut and head following ingestion of a P. falciparum-infected blood meal (Marquez et al., 2011). Although AsILP expression was not induced in response to ingestion of blood alone, the A. stephensi midgut is populated with Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Djadid et al., 2011; Rani et al., 2009), including dominant Gram-negative Asaia sp. that can expand with blood feeding (Favia et al., 2007; Hughes et al., 2014), and with yeast symbionts (Ricci et al., 2011) that could contribute to induction of AsILP expression during parasite infection. To isolate and study these signals in a manner that is not possible in vivo, we stimulated immortalized A. stephensi (ASE) cells in vitro with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Horton et al., 2011; Pakpour et al., 2012; Pakpour et al., 2013) and zymosan (Han et al., 1999; Heard et al., 2005) as representative Gram-negative and fungal microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), with soluble P. falciparum products (Pakpour et al. 2012), or with human insulin. ASE cells express AsILP1, 3, and 5, genes that are induced by physiological concentrations of human insulin and P. falciparum infection in A. stephensi (Marquez et al., 2011). However, ASE cells express only very low levels of AsILP2 and do not express AsILP4 (data not shown). Despite this fact, ASE signaling responses were surprisingly analogous to those in the midgut (Marquez et al., 2011). In particular, human insulin induced ASE expression of AsILP1, 3, and 5 (Figs. 1A, B, C). While stimulation with a low concentration (3.6 parasite equivalents/cell) of soluble P. falciparum products (PfPs; Pakpour et al., 2012) had no effect on AsILP expression, stimulation with a 10-fold higher PfPs concentration (36 parasite equivalents/cell) significantly increased expression of AsILP1, 3, and 5 relative to untreated controls (Figs. 1A, B, C). In contrast, stimulation with LPS, an activator of IMD signaling, significantly decreased expression of AsILP1 and AsILP3 relative to control (Figs. 1A, B), while zymosan, an activator of Toll signaling, had no significant effect on AsILP expression, suggesting that bacterial and fungal MAMPs that induce Toll/IMD signaling do not contribute to induction of AsILP expression during P. falciparum infection in A. stephensi.

Figure 1. Soluble P. falciparum products and human insulin, but not LPS or zymosan, induced AsILP gene expression.

ASE cells were stimulated for 2 hours and homogenized in TriZOL for RNA extraction. AsILP1, 3, and 5 transcript levels were quantified by qRT-PCR using the −ΔΔCt method and were analyzed relative to matched controls by t-test. Gene expression data are represented as mean −ΔΔCt values ± SEM from 4–6 biological replicates on a Log2 scale (1 Ct value = 2 fold change, untreated controls set at 0). *p≤0.05

2.2 AsILP expression was dependent on both IIS-associated MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling

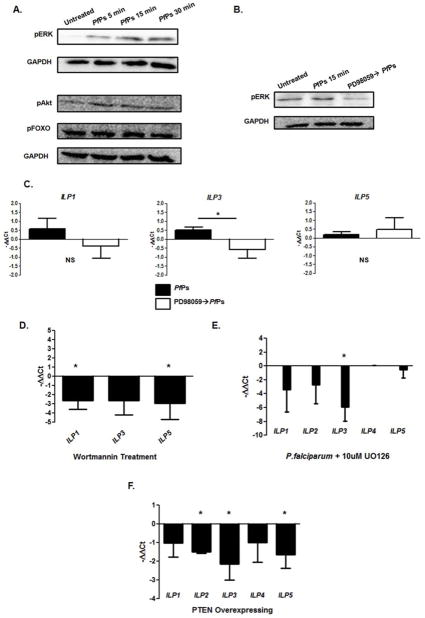

We previously observed that P. falciparum induction of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) expression in ASE cells (Lim et al., 2005) and in the A. stephensi midgut is dependent on activation of both MEK/ERK (Surachetpong et al., 2009) and PI3K/Akt (Corby-Harris et al., 2010; Luckhart et al., 2013) signaling. Here we have demonstrated that PfPs and human insulin induce AsILP transcription and that this signaling is distinct from pathways activated by LPS (Imd) and zymosan (Toll) that decrease or do not induce AsILP expression, respectively (Fig. 1). Thus, we reasoned that expression of AsILPs in A. stephensi could be regulated by MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling. Our analyses revealed that stimulation of ASE cells with PfPs led to increased phosphorylation of the MEK/ERK branch of IIS (Fig. 2A), with statistically significant increases in phosphorylated ERK levels relative to control at all timepoints after stimulation. In contrast, no changes in phosphorylation of Akt or the downstream transcription factor FOXO were observed in two independent replicates. These observations suggested that inducible MEK/ERK signaling regulates AsILP expression in response to PfPs stimulation, but did not preclude the involvement of steady-state PI3K/Akt signaling in the synthesis of AsILP transcripts for storage and later translation. To test these hypotheses, we utilized two approaches established in our previous studies for inhibition of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling. We used the MEK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 (Surachepong et al., 2009) and the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (Lim et al., 2005; Pakpour et al., 2012) as well as overexpression of A. stephensi phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN, Hauck et al., 2013), the endogenous inhibitor of PI3K/Akt signaling, to query regulation of inducible and baseline AsILP expression, respectively. Pre-treatment of ASE cells with PD98059 for 1 hour prior to stimulation, prevented PfPs-induced ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2B) and significantly repressed AsILP3 expression (Fig. 2C). MEK inhibition using PD98059 also reduced AsILP1 expression (Fig. 2C), though this finding was not statistically significant. While stimulation with PfPs had no effect on Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 2A), treatment with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin significantly reduced the expression of AsILP1 and AsILP5 relative to untreated controls, suggesting that constitutive PI3K/Akt signaling contributes to basal AsILP expression (Fig. 2D). To determine whether analogous signaling was evident in vivo, we provided A. stephensi with a P. falciparum-infected bloodmeal supplemented with either UO126 or diluent as a control. As in ASE cells (Fig. 2C), chemical inhibition of MEK in the midgut (Fig. S1) significantly decreased P. falciparum-induced AsILP3 expression, with non-significant downward trends for AsILP1, 2, and 5 (Fig. 2E). PTEN overexpression inhibited baseline AsILP expression in the midgut epithelium of non-fed A. stephensi relative to non-transgenic controls with significant repression of AsILP2, 3, and 5 and non-significant downward trends for AsILP1 and 4 (Fig. 2F). Collectively, these data revealed that inducible AsILP expression requires MEK-ERK signaling while PI3K/Akt signaling controls steady-state AsILP expression.

Figure 2. Soluble P. falciparum products signal through IIS to induce AsILP expression.

(A) Representative western blots from ASE cells stimulated with PfPs for 5, 15, or 30 min and analyzed for pERK, pAkt, and pFOXO levels relative to GAPDH as a loading control. (B) ASE cells were pre-treated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 for 1 hour, stimulated for 15 min with PfPs and then harvested for western blot analysis or (C) pre-treated with PD98059 for 1 hour, stimulated for 2 hours and harvested for qRT-PCR analysis of AsILP gene expression relative to matched untreated and PfPs only treated controls. (D) ASE cells were treated with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin for 3 hours and harvested for qRT-PCR analysis of AsILP gene expression. (E) Midguts from mosquitoes provided a meal of P. falciparum infected RBCs +/− the MEK inhibitor UO126 were dissected 24 hours after feeding for qRT-PCR analysis of AsILP gene expression. (F) Midguts from 3 day old, PTEN transgenic and sibling non-transgenic control A. stephensi were dissected for qRT-PCR analysis of AsILP gene expression. Gene expression data are represented as mean −ΔΔCt values ± SEM from 3–5 biological replicates on a Log2 scale (1 Ct value = 2 fold change, untreated controls set at 0). Data from (A, F) were normalized by rank transformation. Western blot densitometry data (A) and gene expression data (C–F) were analyzed relative to matched controls by ANOVA or t-test, respectively. Western blots (A) were independently replicated twice for pAkt and pFOXO or 4 times for pERK. *p≤0.05

2.3 Treatment with antisense morpholinos directed against AsILP3 or AsILP4 decreased P. falciparum development in A. stephensi

In ASE cells (Fig. 1B) and in the A. stephensi midgut and head (Marquez et al., 2011), AsILP3 expression is induced by parasite signaling. AsILP4 expression is further restricted, with induction only in the midgut and only by P. falciparum infection (Marquez et al., 2011). In field-collected Anopheles gambiae, we identified coding sequence SNPs in AgILP3 (Horton et al., 2010) and AgILP4 (unpublished data) that are significantly associated with natural P. falciparum infection, suggesting functional involvement of these ILPs in the host response. To determine whether AsILP3 and 4 were functionally associated with P. falciparum infection in A. stephensi, we treated A. stephensi with translation blocking antisense morpholinos (Pietri et al., 2014) that repress AsILP3 and 4 peptide levels in vitro and in vivo (Cator et al., 2015). Treatment of mosquitoes with each morpholino significantly reduced the prevalence (percentage of mosquitoes infected) and intensity (oocysts/infected midgut) of P. falciparum infection. Specifically, treatment with anti-AsILP3 morpholino reduced infection prevalence from 68.1% to 51.5% (Fig. 3A) and reduced infection intensity by more than 30% (2.54 to 1.81 oocysts/infected midgut; Fig. 3B). Similarly, treatment with anti-AsILP4 morpholino decreased infection prevalence from 60.9% to 48.2% (Fig. 3C) and infection intensity from 2.0 to 1.51 oocysts/midgut (Fig. 3D). Given that we have previously shown morpholinos efficiently target midgut proteins for knockdown (Pietri et al., 2014), these effects are likely due to a reduction in midgut ILPs, but we cannot fully discount contributions from knockdown in other tissues. Nevertheless, these data suggested that AsILP3 and AsILP4 function in a manner similar to that of ingested human insulin (Pakpour et al., 2012) to promote P. falciparum development in the midgut.

Figure 3. Treatment with anti-AsILP3 and anti-AsILP4 morpholinos reduced the prevalence and intensity of P. falciparum infection in A. stephensi.

Mosquitoes were fed either anti-AsILP3 (A, B) or anti-AsILP4 (C, D) morpholinos in saline-ATP and then provided a meal of human RBCs infected with P. falciparum three days later. Ten days later, midguts were dissected and stained with mercurochrome for visualization of oocysts to record both infection prevalence (A, C, percentage of mosquitoes infected) and infection intensity (B, D, number of oocysts/infected midgut). Data are reported as means for 4 replicates with separate cohorts of A. stephensi. Infection prevalence and intensity data were analyzed using goodness of fit (chi-square) and unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, respectively. *p≤0.05

2.4 Treatment with antisense morpholinos directed against AsILP3 and AsILP4 increased immune effector gene expression and parasite killing in A. stephensi

To determine whether decreased oocyst numbers in morpholino-treated A. stephensi were associated with increased anti-parasite responses, we quantified transcript levels for A. stephensi orthologs of several gene targets known to regulate the A. gambiae anti-parasite response at 1, 6, and 24 hours post-infection in antisense morpholino-treated mosquitoes relative to controls. We also quantified transcript levels for Pfs16 (a sexual stage-specific expression marker for P. falciparum gametocyte to zygote stages; Berry et al., 2009; Luckhart et al., 2013) and Pfs25 (a marker for gametocyte to oocyst stages; Berry et al., 2009; Luckhart et al., 2013) in the same samples as an indication of relative abundance of sexual stage parasites in the midgut lumen. Interestingly, treatment with antisense morpholinos directed against AsILP3 and AsILP4 produced distinctly different effects on expression of immune mediators and on relative parasite abundance (Fig. 4). In particular, treatment with anti-AsILP3 morpholino had no effect on immune gene expression at 1 or 6 hours post-infection relative to controls. However, by 24 hours post-infection, expression of NOS, APL1, TEP1, and LRIM1 were significantly increased (Fig. 4A). In contrast, treatment with anti-AsILP4 morpholino was associated with rapid and significant induction of NOS expression at 1 hour and of APL1, TEP1, and LRIM1 expression at 1 and 6 hours post-infection relative to controls, while only NOS expression was significantly induced at 24 hours post-infection (Fig. 4B). There were no significant differences in expression markers for relative parasite abundance between anti-AsILP3 morpholino-treated mosquitoes and controls at any of the timepoints examined (Fig. 4C). However, expression of Pfs25 was significantly repressed at 24 hours post-infection in mosquitoes treated with anti-AsILP4 morpholino relative to controls (Fig. 4D), a pattern consistent with early induction of immune genes in these mosquitoes (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these observations suggested that AsILP3 and AsILP4 regulate mosquito immune gene expression and parasite killing through kinetically distinct mechanisms, with AsILP3 acting on parasites during or after invasion of the midgut epithelium and AsILP4 affecting parasites in the midgut lumen prior to invasion.

Figure 4. Treatment with anti-AsILP3 and anti-AsILP4 morpholinos increased immune effector gene expression and parasite killing in the mosquito midgut following P. falciparum infection.

Mosquitoes were fed either anti-AsILP3 (A, C) or anti-AsILP4 (B, D) morpholinos in saline-ATP and then provided a meal of human RBCs infected with P. falciparum three days later. Midguts were dissected at 1, 6, and 24 hours post-feeding for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis of: (A, B) expression of immune effector genes or (C, D) markers of sexual state parasites (Pfs16, gametocyte-zygote; Pfs25, gametocyte-oocyst). Gene expression data from 3–7 replicates with separate cohorts of A. stephensi are represented as mean −ΔΔCt values ± SEM on a Log2 scale (1 Ct value = 2 fold change, infected controls set at 0). Data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Fisher’s test. *p≤0.05

3. Discussion

Our data affirm previous observations that P. falciparum can induce the expression of AsILPs (Marquez et al., 2011), but extend these observations by demonstrating that IIS is functionally required for parasite-induced expression of AsILPs. The synthesis of AsILPs, in turn, represses NF-κB-dependent host immune defenses through as yet unknown signaling pathways to facilitate parasite survival (Fig. 5). We summarize these observations below in the context of published studies.

Figure 5. A model for IIS regulation of AsILP-dependent control of P. falciparum development.

P. falciparum-derived signals activate MEK/ERK in the context of basal PI3K/Akt signaling to induce the expression of AsILPs (Panel 1). In the midgut, AsILP signaling decreases the expression of immune effector genes through distinct mechanisms (Panel 2), creating a more favorable environment for infection and increasing parasite survival (Panel 3). Inhibition of PI3K/Akt represses steady-state AsILP synthesis, while inhibition of MEK/ERK signaling abrogates P. falciparum-induced AsILP expression (Panel 4). AsILP knockdown results in increased defense responses to P. falciparum (Panel 5), killing parasites and decreasing infection levels in the mosquito (Panel 6).

Using ASE cells as a surrogate for the host response to parasite signaling in vivo, we affirmed that inducible AsILP expression is tuned to signaling by human insulin and P. falciparum and showed that AsILP expression is not activated by sensing of prototypical MAMPs that activate the Toll (zymosan) and IMD (LPS) pathways. These MAMPs did not activate and, in fact, repressed AsILP expression in ASE cells. In particular, zymosan had no significant effect on AsILP expression and stimulation with LPS decreased the expression of AsILP1 and AsILP3 (Figs.1A, B). Given that activation of Toll and IMD signaling in D. melanogaster can decrease IIS and metabolic stores (DiAngelo et al., 2009, Dionne et al., 2006), LPS-mediated reductions in AsILP expression could contribute mechanistically to these phenomena. Conversely, stimulation with PfPs increased AsILP expression (Fig. 1), indicating that PfPs signaling is distinct from that of Toll/IMD activators. In particular, PfPs induced AsILP expression through IIS, akin to induction of AsILP expression by physiological concentrations of human insulin (Marquez et al. 2011). In support, stimulation with PfPs activated the MEK/ERK branch of the IIS pathway (Fig. 2A). Chemical inhibition of MEK attenuated this signaling event (Fig. 2B) and reversed the effects of PfPs and P. falciparum infection on AsILP expression (Figs. 2C, E). While Akt phosphorylation was not induced by PfPs in vitro (Fig. 2A), chemical inhibition of PI3K using wortmannin reduced AsILP expression in unstimulated cells (Fig. 2D). Further, overexpression of the PI3K/Akt signaling inhibitor PTEN significantly reduced AsILP expression in the midgut of non-fed A. stephensi relative to non-transgenic controls (Fig. 2F), suggesting that MEK/ERK signaling regulates inducible AsILP expression for response to infection and stress, while PI3K/Akt signaling regulates steady-state AsILP expression for normal cellular growth and metabolism. Collectively, these data also suggest that feed-forward induction of ILPs by IIS activation is conserved from invertebrates to mammals (Khoo et al., 2003, Leibiger et al., 1998).

Although we have not identified the parasite ligand(s) responsible for inducing AsILP synthesis in the mosquito, parasite glycosylphophatidylinositols (GPIs), which are insulin-mimetic and can activate IIS in the A. stephensi midgut within 30 minutes after ingestion (Lim et al., 2005), could function in this capacity. The induction of AsILP expression by P. falciparum infection (Marquez et al., 2011) and by PfPs (Fig. 1) also affirms that live pathogen signaling – similar to P. aeruginosa-induced immunosuppression via DAF2 signaling in C. elegans (Evans et al., 2008) – can induce AsILPs, but is not necessary for this response. Further, the levels of AsILP induction in vitro by PfPs (Fig. 1) and in vivo following infection (Marquez et al., 2011) – both roughly 2–3 fold relative to control – suggest that signals from parasite GPIs or other factors are predominant in regulating AsILP expression. Accordingly, we suggest that any other midgut-associated MAMPs that could activate AsILP expression likely contribute minimally if at all to AsILP expression in vivo. This speculation is supported by our observations that an uninfected blood meal, which can induce significant proliferation of A. stephensi microbiota (Hughes et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2011), has no effect on AsILP expression relative to non-fed controls (Marquez et al., 2011). Despite the concordance of these data, we cannot ultimately exclude minor contributions from other microbial factors, as these can activate a wide network of pathways, including multiple MAPKs (Lee & Kim, 2007).

The concept that parasite insulin mimicry activates mosquito IIS during infection is suggestive of immune evasion by the parasite, given the known inverse relationship between IIS and immunity (Demas et al., 2011; DiAngelo et al., 2009). To test this hypothesis of immunosuppression, we used anti-AsILP morpholino treatments to query the effects of P. falciparum-induced AsILP3 and AsILP4 (Marquez et al., 2011) on the expression of A. stephensi orthologs of known anti-parasite immune effectors in A. gambiae, and on parasite development in vivo. Treatment with morpholinos directed against both AsILPs significantly decreased the prevalence and intensity of P. falciparum infection (Fig. 3). Further analysis revealed that AsILP4 appears to affect early expression (1–6 hours post-infection) of immune effectors (Fig. 4B), while the effects of AsILP3 are delayed, only appearing at 24 hours post-infection (Fig. 4A). These patterns were temporally associated with parasite killing in the midgut lumen (Figs. 4C, D), suggesting that parasite-induced AsILPs are in fact immunosuppressive.

The upregulation of an array of anti-parasite immune effectors by AsILP3 and 4 knockdown suggests that AsILPs can broadly inhibit NF-κB-dependent signaling. Among these anti-parasite effectors, inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species contribute to P. falciparum killing in the A. stephensi midgut lumen (Ali et al., 2010; Hurd & Carter, 2004; Luckhart et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 2007), while a complex of NF-κB-regulated IMD pathway components including complement-like TEP1 (Blandin et al., 2004), the leucine-rich repeat protein LRIM1 (Fraiture et al., 2009) and APL1 (Mitri et al., 2009) have been demonstrated to act maximally against ookinetes that have completed passage through the A. gambiae midgut epithelium and have come to rest in the basal labyrinth under the basal lamina. Activity of mosquito defensin against oocyst development has been reported in some but not all mosquito-parasite combinations (Antonova et al, 2009; Blandin et al., 2002; Kokoza et al., 2010). In our studies, the upregulation of these anti-parasite effectors following AsILP knockdown (Fig. 4) was associated with reduced abundance of both early and invading ookinetes as well as early oocysts based on expression of the sexual stage-specific markers Pfs16 and Pfs25 (Berry et al., 2009; Luckhart et al., 2013) and direct parasite counts. Detailed studies of the interaction between P. falciparum ookinetes and the A. stephensi midgut using electron microscopy have shown that at 24 hours post-infection ookinetes are present at this time only in the midgut lumen, with invasion of the epithelium occurring between 32–36 hours post-infection (Meis & Ponnudurai, 1987). Therefore, we suggest that induction of AsILP4 suppresses early anti-parasite gene expression during the first 24 hours of infection, a time when ookinetes have formed in the lumen but have not yet invaded the midgut epithelium and that AsILP3 induction suppresses later anti-parasite gene expression to protect parasites during and after invasion.

In general, our data suggest that AsILPs negatively regulate anti-P. falciparum inducible NOS and IMD signaling, both of which are conserved among Anopheles species (Garver et al., 2009; Gupta et al., 2009; Herrera-Ortiz et al., 2004; Luckhart et al., 1998; Vijay et al., 2011), but with distinct kinetics as shown here with A. stephensi. These differences may be due to AsILP-specific differences in the timing of peptide secretion or to differential activation of distinct signaling pathways, biology that we are now exploring. In particular, A. aegypti ILP3 (AaILP3) has been shown to bind to the insulin receptor, while AaILP4 binds to an uncharacterized mosquito membrane protein (Wen et al., 2010), suggesting that AsILPs could signal through multiple receptors to regulate anti-parasite effector genes. Alternatively, AsILP-specific activation of IIS pathway proteins, most notably FOXO, ERK and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) could facilitate diverse direct effects on effector gene transcription as well as modulation of NF-κB-dependent signaling (Becker et al., 2010; Pakpour et al., 2012; Zou et al., 2013; Surachetpong et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2005). Hence, further study of AsILPs and mechanisms whereby AsILPs signal host mosquito cells are likely to provide novel insights into parasite manipulation of mosquito defenses against infection.

Beyond host immunity, the functional diversity of mosquito ILPs is likely to impact vectorial capacity through effects on feeding behavior (Cator et al., 2015; Nassel, 2012), longevity (Evans et al., 2008, Broughton et al., 2010) and reproduction (Brown et al., 2008; Gulia-Nuss et al., 2011; Sim & Denlinger, 2009). Notably, phylogenetic analysis revealed that AsILPs are more divergent as a group than are D. melanogaster ILPs (DILPs) (Marquez et al., 2011). AaILPs are similarly diverse, as ILP3 and ILP4 divergently regulate carbohydrate and lipid metabolism while having overlapping effects on gonadotropic activity and IIS activation (Wen et al., 2010). DILPs, in contrast, are highly redundant, with compensatory effects observed upon knockdown, and appear to function in networks. For example, RNAi-mediated knockdown of DILP2 increased DILP3 and DILP5 expression (Broughton et al., 2010) and knockdown of multiple DILPs was necessary to observe a measurable effect on fly growth (Zhang et al., 2009). While it is likely that AsILPs cooperate to regulate mosquito physiology, our data also suggest that AsILPs regulate parasite development as well through distinct effects on host immune effector genes. Hence, it may be possible to precisely manipulate specific AsILPs to generate genetically modified mosquitoes that exhibit enhanced resistance coupled with enhanced survivorship and reproduction for sustainable malaria transmission control.

On a broader scale, our work has implications for understanding the evolutionary biology of both P. falciparum and IIS. In particular, P. falciparum-derived signals and insulin can activate A. stephensi IIS to induce immunosuppressive ILPs that facilitate parasite survival (Fig. 5). Given the highly conserved nature of IIS (Luckhart & Riehle, 2007), immunosuppressive ILPs could facilitate P. falciparum infection in other Anopheles species. A connection with biology in the human host is also likely. Human malaria is associated with hyperinsulinemia (Phillips et al., 1993; White et al., 1983), perhaps due to GPI signaling (Schofield and Hackett, 1993). Taken together, these observations highlight the existence of a co-evolved host interface that facilitates immune evasion by malaria parasites. Specifically, hyperinsulinemia of ingested blood can decrease mosquito anti-parasite defenses directly (Pakpour et al., 2012) and can also induce the synthesis of immunosuppressive mosquito AsILPs through a heterologous feedback loop (Marquez et al., 2011). Further, P. falciparum can directly activate AsILP expression to dampen immunity through mosquito IIS, as shown here, collectively suggesting that P. falciparum manipulates insulin and ILP synthesis in mammals and mosquitoes to facilitate their development and transmission at this critical interface that defines malaria (Fig. 5).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1 AsILP gene expression

Immortalized, embryo-derived A. stephensi (ASE) cells were maintained in modified minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum at 28°C under 5% CO2. Cells were plated at a density of 250,000 cells/mL and allowed to rest for 24 hours prior to stimulation with human insulin (1.7 μM; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 μg/mL; Sigma Aldrich), Saccharomyces cerevisiae zymosan (10 μg/mL; Sigma Aldrich), or purified soluble P. falciparum products (PfPs, 3.6 or 36 parasite equivalents/cell; Pakpour et al., 2012) for 2 hours. Ingestion of 1–2 μl of blood by A. stephensi from a host with a 10% parasitemia, typical in peripheral blood samples from life-threatening P. falciparum infections (Bruce-Chwatt, 1971), would lead to midgut infections of 250 to 550 parasites per midgut epithelial cell (Lim et al., 2005). Our in vitro assays of 3.6 or 36 parasite equivalents/cell, therefore, would be typical of mosquito feeding on hosts with lower (0.5 to 1%) parasitemias (Markell et al., 1999). Following stimulation, cells were transferred into TriZOL (Invitrogen) and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) using AsILP1-5 primers as previously described (Marquez et al., 2011). Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen et al., 2008) and AsILP expression in stimulated cells was normalized against A. stephensi ribosomal protein S7 (RPS7) for loading and then against expression levels in matched, untreated controls. These experiments were replicated 4–6 times using independent preparations of ASE cells.

For analyses of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt-dependent AsILP expression in vitro, cells were pre-treated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (10 μM; Surachetpong et al., 2009; Selleckchem, Houston, TX) for 1 hour prior to stimulation with PfPs (36 parasite equivalents/cell) or treated for 3 hours with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin without further stimulation (10 μM; Lim et al., 2005, Selleckchem) and data were analyzed as described above. For analyses of MEK/ERK-dependent AsILP expression in vivo, midguts from 15–20 A. stephensi were dissected intro TriZOL (Invitrogen) 24 hours after being fed either an unsupplemented, P. falciparum infected blood meal or a P. falciparum-infected blood meal supplemented with the MEK inhibitor UO126 (10 μM; Surachetpong et al., 2009; Selleckchem). For analyses of PI3K/Akt-dependent AsILP expression in vivo, midguts from a total of 15–20 three day old, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) transgenic (Hauck et al., 2013) or non-transgenic sibling A. stephensi females were dissected for quantitative real-time PCR as described above. Data are reported as mean −ΔΔCt values ± SEM on a Log2 scale (1 Ct value = 2 fold change). MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt-dependent AsILP expression experiments in vitro and in vivo were replicated with 3–5 independent preparations of ASE cells and 3–5 separate cohorts of A. stephensi, respectively.

4.2 Western blotting of soluble P. falciparum product (PfPs)-stimulated A. stephensi cells

ASE cells were maintained as described above and stimulated with PfPs (36 parasite equivalents/cell) for 5, 15, or 30 minutes. Cells were harvested into cell extraction buffer (Invitrogen), incubated at 4°C for 1 hour and periodically vortexed. Cell lysates were then cleared at 16,000 g for 10 min and protein supernatants were mixed with sample loading buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 10% SDS, 0.006% bromophenol blue, 130 mM dithiothreitol) and boiled for 5 minutes. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20(TBS-T) for 1 hour at room temperature. For detection of phosphorylated ERK (pERK), membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:10,000 dilution of anti-pERK antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) in 5% non-fat dry milk. Membranes were then washed 3X with TBS-T for 5 minutes and incubated with a 1:10,000 dilution of secondary HRP conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Sigma Aldrich) in 5% non-fat dry milk overnight. Detection of phosphorylated FOXO (pFOXO; Cell Signaling,1:1000 primary, 1:2000 goat anti-rabbit secondary), phosphorylated Akt (pAkt; Cell Signaling, 1:1000 primary, 1:3000 goat anti-rabbit secondary) and GAPDH (Cell Signaling, 1:10,000 primary, 1:20,0000 goat anti-rabbit secondary) followed the same protocol. Proteins were visualized by incubating membranes with SuperSignal West Dura chemiluminescent reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 3 minutes and exposing on an Image Station 4000 Pro digital imager (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 1–5 minutes. Densitometry of pERK western blots was performed using the ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) gel analysis tool. Data were normalized to untreated control groups as well as a GAPDH loading control. These analyses were replicated 2–4 times with independent preparations of ASE cells.

4.3 Morpholino-mediated knockdown of AsILPs in vivo

Knockdown of AsILP3 and AsILP4 in adult female A. stephensi was performed by feeding translation blocking anti-AsILP3 or anti-AsILP4 morpholinos (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR) as previously described and validated in vivo (Pietri et al., 2014) and in vitro (Cator et al., 2015). In brief, anti-AsILP3 (5′-TCGTGGACGACATCTTGACAGAGGT-3′) or anti-AsILP4 (5′-CGTGGAACTTTCATCTCAAGGACCT-3′) morpholinos at a stock concentration of 500 μM were diluted to 10 μM in saline (15 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.0) with ATP (Sigma Aldrich) added to a final concentration 1 mg/ml as a feeding stimulant. Immediately prior to feeding, morpholino solutions were warmed in a water bath at 37°C for 10 minutes. A morpholino standard control, targeting a human beta-globin intron (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) was provided at 10 μM in saline-ATP to control mosquitoes. Cohorts of 50–60 newly emerged female mosquitoes were provided with water only (no sucrose) for 24 hours and then provided control-morpholino, anti-AsILP3 morpholino, or anti-AsILP4-morpholino in saline-ATP via a Hemotek artificial circulation system (Discovery Workshops, Accrington, UK). After 30 minutes, unfed mosquitoes were removed from experimental cohorts. Mosquitoes were maintained on cotton pads soaked in 10% sucrose and on day 3 post-morpholino feeding were provided a meal of human P. falciparum-infected red blood cells (RBCs).

4.4 P. falciparum culture and mosquito infection

The NF54 strain of P. falciparum was initiated at 1% parasitemia in 10% heat-inactivated human serum and 6% washed RBCs in RPMI 1640 with HEPES (Gibco/Invitrogen) and hypoxanthine. At days 15–17, stage V gametocytes were evident and exflagellation was evaluated at 200X magnification with phase-contrast or modified brightfield microscopy the day before and day of feeding by observation of blood smears and before addition of fresh media. Female A. stephensi were provided water only (no sucrose) for 24 hours and then fed a meal of P. falciparum-infected RBCs using a Hemotek artificial circulation system (Discovery Workshops). Mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 30 minutes and were then maintained on cotton pads soaked in 10% sucrose until day 10 post-infection. On day 10, midguts were dissected and stained with 0.5% mercurochrome for visualization of P. falciparum oocysts by microscopy. Analyses of morpholino effects on parasite infection were replicated with four independent infections consisting of 14–29 female A. stephensi per group.

4.5 qPCR detection of immune gene expression in the mosquito

Cohorts of 15–20 morpholino-fed female A. stephensi were dissected 1, 6, or 24 hours after provision of a P. falciparum-infected blood meal and midguts were collected into TriZOL (Invitrogen) for extraction of total RNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using the QuantiTec Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using gene-specific primers for A. stephensi orthologs of defensin (ASTE011281), NOS (ASTE008593), TEP1 (ASTE010227), APL1 (ASTEI02571), LRIM1 (ASTE000814), and S7 with SYBR Green PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (Pakpour et al., 2013; Hauck et al., 2013). For relative quantitation of P. falciparum in the same samples, qPCR was performed using gene-specific primers for Pfs16 (gametocyte-zygote; Berry et al., 2009; Luckhart et al., 2013) and Pfs25 (gametocyte-oocyst; Berry et al., 2009; Luckhart et al., 2013) with SYBR Green PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (Luckhart et al., 2013 Since expression of A18S rRNA is high in all parasite stages and varies with the parasitemia, this gene and the ribosomal protein S7 gene (A. stephensi) were used to normalize parasite gene target data. Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen et al., 2008). These assays were completed with three separate cohorts of P. falciparum-infected A. stephensi.

4.6 Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using Graphpad Prism 5.02 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). For in vitro analysis of AsILP expression in response to PAMPS (Fig. 1), data were normalized and compared to untreated controls by t-test. AsILP expression levels following chemical inhibition of MEK or PI3K (Fig. 2) were analyzed relative to matched controls (PfPs only or untreated) by t-test. AsILP expression levels in PTEN transgenic mosquitoes were analyzed relative to matched non-transgenic siblings by t-test following rank transformation. ERK phosphorylation in ASE cells in response to stimulation with PfPs (Fig. 2A) was analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test following rank transformation. Oocyst data from multiple replicates were pooled based on the determination by ANOVA that oocyst intensities did not differ among controls (individual replicate data provided in Table S1). Infection prevalence and intensity data were then analyzed using goodness of fit (chi-squared) and unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, respectively. Analyses of immune gene expression and sexual stage parasite marker expression in the midgut (Fig. 4) were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Fisher’s exact test to analyze differences between control mosquitoes and mosquitoes treated with antisense morpholinos targeting AsILPs at matched timepoints. For all analyses, differences were considered significant when p≤0.05.

Supplementary Material

Cohorts of 30 female A. stephensi were provided either an unsupplemented, P. falciparum-infected blood meal or a P. falciparum-infected blood meal supplemented with the MEK inhibitor UO126 (10 μM; Surachetpong et al., 2009; Selleckchem). Midguts were collected 1 hour after feeding and protein extracts were used for western blotting to detect phosphorylated ERK. Values were normalized to Coomassie brilliant blue stain for total protein with proportional levels indicated below the blots. Protein samples were obtained from a biological replicate in which provision of UO126 inhibited AsILP expression.

Supplementary Table 1. Effects of anti-AsILP morpholino treatment on the prevalence and intensity of P. falciparum in A. stephensi by replicate.

Highlights.

ILP expression is induced by P. falciparum activation of mosquito insulin signaling

ILPs, like human insulin, promote P. falciparum development in A. stephensi

ILP3 and ILP4 produce kinetically distinct effects on the mosquito immune response

P. falciparum may have co-opted mosquito insulin signaling to increase its survival

Acknowledgments

We thank Kong Wai Cheung and Caitlin Tiffany for assistance with P. falciparum culture and mosquito infection and Dr. Nazzy Pakpour for critical review of this manuscript. Funding for these studies was provided by the United States National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH NIAID) grants AI073745, AI107263 (MAR, SL), and AI080799 (SL) as well as an F31-NRSA AI100589 (JEP).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jose E. Pietri, Email: jepietri@ucdavis.edu.

Eduardo J. Pietri, Email: ejpietri@ucdavis.edu.

Rashaun Potts, Email: rapotts@ucdavis.edu.

Michael Riehle, Email: mriehle@ag.arizona.edu.

References

- Ali M, Al-Olayan EM, Lewis S, Matthews H, Hurd H. Naturally occuring triggers that induce apoptosis-like programmed cell death in Plasmodium berghei ookinetes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova Y, Alvarez KS, Kim YJ, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. The role of NF-kappaB factor REL2 in the Aedes aegypti immune response. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Loch G, Beyer M, Zinke I, Aschenbrenner AC, Carrera P, et al. FOXO-dependent regulation of innate immune homeostasis. Nature. 2010;463:369–373. doi: 10.1038/nature08698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry A, Deymier C, Sertorio M, Witkowski B, Benoit-Vical F. Pfs 16 pivotal role in Plasmodium falciparum gametocytogenesis: a potential antiplasmodial drug target. Exp Parasitol. 2009;121:189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandin S, Moita LF, Köcher T, Wilm M, Kafatos FC, Levashina EA. Reverse genetics in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae: targeted disruption of the Defensin gene. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:852–856. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandin S, Shiao SH, Moita LF, Janse CJ, Waters AP, Kafatos FC, et al. Complement-like protein TEP1 is a determinant of vectorial capacity in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Cell. 2004;116:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo W, Stocker H, Ikeya T, Rinkelen F, Fernandez R, Hafen E. An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr Biol. 2001;11:213–221. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton S, Alic N, Slack C, Bass T, Ikeya T, Vinti G, et al. Reduction of DILP2 in Drosophila triages a metabolic phenotype from lifespan revealing redundancy and compensation among DILPs. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Clark KD, Gulia M, Zhao Z, Garczynski SF, Crim JW, et al. An insulin-like peptide regulates egg maturation and metabolism in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5716–5721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800478105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Essential Malariology. John Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cator LJ, Pietri JE, Murdock CC, Ohm JR, Lewis EE, Read AF, et al. Immune response and insulin signaling alter mosquito feeding behavior to enhance malaria transmission potential. Sci Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1038/srep11947. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AM, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. The Anopheles innate immune system in the defense against malaria infection. J Innate Immun. 2014;6:169–181. doi: 10.1159/000353602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby-Harris V, Drexler A, Watkins de Jong L, Antonova Y, Pakpour N, Ziegler R, et al. Activation of Akt signaling reduces the prevalence and intensity of malaria parasite infection and lifespan in Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001003. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demas GE, Adamo SA, French SS. Neuroendocrine-immune crosstalk in vertebrates and invertebrates: implications for host defence. Funct Ecol. 2011;25:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- DiAngelo JR, Bland ML, Bambina S, Cherry S, Birnbaum MJ. The immune response attenuates growth and nutrient storage in Drosophila by reducing insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20853–20858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne MS, Pham LN, Shirasu-Hiza M, Schneider DS. Akt and FOXO dysregulation contribute to infection-induced wasting in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1977–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djadid N, Jazayeri H, Raz A, Favia G, Ricci I, Zakeri S. Identification of the midgut microbiota of An. stephensi and An. maculipennis for their application as a paratransgenic tool against malaria. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler A, Nuss A, Hauck E, Glennon E, Cheung K, Brown MR, et al. Human IGF1 extends lifespan and enhances resistance to Plasmodium falciparum infection in the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:208–217. doi: 10.1242/jeb.078873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler AL, Pietri JE, Pakpour N, Hauck E, Wang B, Glennon EK, et al. Human IGF1 regulates midgut oxidative stress and epithelial homeostasis to balance lifespan and Plasmodium falciparum resistance in Anopheles stephensi. PLos Pathog. 2014:e1004231. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L, Guex N, Peitsch MC, Bairoch A. New insulin-like proteins with atypical disulfide bond pattern characterized in Caenorhabditis elegans by comparative sequence analysis and homology modeling. Genome Res. 1998;8:348–353. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EA, Chen WC, Tan MW. The DAF-2 insulin-like signaling pathway independently regulates aging and immunity in C. elegans. Aging Cell. 2008;7:879–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EA, Kawli T, Tan MW. Pseudomonas aeruginosa suppresses host immunity by activating the DAF-2 insulin-like signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000175. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia G, Ricci I, Damiani C, Raddadi N, Crotti E, Marzorati M, et al. Bacteria of the genus Asaia stably associate with Anopheles stephensi, an Asian malarial mosquito vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9047–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610451104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraiture M, Baxter RHG, Steinert S, Chelliah Y, Frolet C, Quispe-Tintaya W, et al. Two mosquito LRR proteins function as complement control factors in the TEP1-mediated killing of Plasmodium. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, Kim DH, Sifri CD, Calderwood SB, et al. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300:1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver LS, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. Caspar controls resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in diverse anopheline species. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000335. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulia-Nuss M, Robertson AE, Brown MR, Strand MR. Insulin-like peptides and the target of rapamycin pathway coordinately regulate blood digestion and egg maturation in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta L, Molina-Cruz A, Kumar S, Rodrigues A, Dixit R, Zamora RE, et al. The STAT pathway mediates late-phase immunity against Plasmodium in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halls ML, Van Der Westhuizen ET, Bathgate RA, Summers RJ. Relaxin family peptide receptors–former orphans reunite with their parent ligands to activate multiple signalling pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:677–691. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YS, Chun J, Schwartz A, Nelson S, Paskewitz SM. Induction of mosquito hemolymph proteins in response to immune challenge and wounding. Dev Comp Immunol. 1999;23:553–562. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(99)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck ES, Antonova-Koch Y, Drexler A, Pietri JE, Pakpour N, Liu D, et al. Overexpression of phosphatase and tensin homolog improves fitness and decreases Plasmodium falciparum development in Anopheles stephensi. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard NA, Holmes CC, Stephens DA, Hand DJ, Dimopoulos G. Bayesian coclustering of Anopheles gene expression time series: study of immune defense response to multiple experimental challenges. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16939–16944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408393102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Ortiz A, Lanz-Mendoza H, Martinez-Barnetche J, Hernandez-Martinez S, Villareal-Trevino C, et al. Plasmodium berghei ookinetes induce nitric oxide production in Anopheles pseudopunctipennis midguts cultured in vitro. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:893–901. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton AA, Lee Y, Coulibaly CA, Rashbrook VK, Cornel AJ, Lanzaro GC, et al. Identification of three single nucleotide polymorphisms in Anopheles gambiae immune signaling genes that are associated with natural Plasmodium falciparum infection. Malar J. 2010;9:160. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton AA, Wang B, Camp L, Price MS, Arshi A, Nagy M, et al. The mitogen-activated protein kinome from Anopheles gambiae: identification, phylogeny and functional characterization of the ERK, JNK and p38 MAP kinases. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:574. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GL, Dodson BL, Johnson RM, Murdock CC, Tsujimoto H, Suzuki Y et al. Native microbiome impedes vertical transmission of Wolbachia in Anopheles mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12498–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408888111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd H, Carter V. The role of programmed cell death in Plasmodium-mosquito interactions. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1459–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo S, Griffen SC, Xia Y, Baer RJ, German MS, Cobb MH. Regulation of insulin gene transcription by ERK1 and ERK2 in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32969–32977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoza V, Ahmed A, Woon-Shin S, Okafor N, Zou Z, Raikhel AS. Blocking of Plasmodium transmission by cooperative action of Cecropin A and Defensin A in transgenic Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8111–8116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003056107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger MJ, Jahan N, Riehle MA, Cao C, Brown MR. Molecular characterization of insulin-like peptide genes and their expression in the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:305–315. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibiger IB, Leibiger B, Moede T, Berggren PO. Exocytosis of insulin promotes insulin gene transcription via the insulin receptor/PI-3 kinase/p70 s6 kinase and CaM kinase pathways. Mol Cell. 1998;1:933–938. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibiger B, Wahlander K, Berggren PO, Leibiger IB. Glucose-stimulated insulin biosynthesis depends on insulin-stimulated insulin gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30153–30156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Gowda DC, Krishnegowda G, Luckhart S. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in Anopheles stephensi by Plasmodium falciparum: mechanism of signaling and the role of parasite glycosylphosphatidylinositols. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2778–2789. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2778-2789.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Kim YJ. Signaling pathways downstream of pattern-recognition receptors and their crosstalk. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:447–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060605.122847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhart S, Vodovotz Y, Ciu L, Rosenberg R. The mosquito Anopheles stephensi limits malaria parasite development with inducible synthesis of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5700–5705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhart S, Riehle MA. The insulin signaling cascade from nematodes to mammals: insights into innate immunity of Anopheles mosquitoes to malaria parasite infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2007;31:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhart S, Giulivi C, Drexler AL, Antonova-Koch Y, Sakaguchi D, Napoli E, et al. Sustained activation of Akt elicits mitochondrial dysfunction to block Plasmodium falciparum infection in the mosquito host. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003180. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markell EK, John DT, Krotoski WA. Medical Parasitology. 8. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez AG, Pietri JE, Smithers HM, Nuss A, Antonova Y, Drexler AL, et al. Insulin-like peptides in the mosquito Anopheles stephensi: Identification and expression in response to diet and infection with Plasmodium falciparum. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;173:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Rehani K, Jope RS, Michalek SM. Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis JF, Ponnudurai T. Ultrastructural studies on the interaction of Plasmodium falciparum ookinetes with the midgut epithelium of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Parasitol Res. 1987;73:500–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00535323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melloul D, Marshak S, Cerasi E. Regulation of insulin gene transcription. Diabetologia. 2002;45:309–326. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0728-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitri C, Jacques JC, Thiery I, Riehle MM, Xu J, Bischoff E, et al. Fine pathogen discrimination within the APL1 gene family protects Anopheles gambiae against human and rodent malaria species. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000576. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A, Okamoto N. Insulin-like and IGF-like peptides in the silkmoth Bombyx mori: discovery, structure, secretion, and function. Front physiol. 2013;16:217. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassel DR. Insulin-producing cells and their regulation in physiology and behavior of Drosophila. Can J Zool. 2012;90:476–488. [Google Scholar]

- Pakpour N, Corby-Harris V, Green GP, Smithers HM, Cheung KW, Riehle MA, et al. Ingested human insulin inhibits the mosquito NF-kappaB-dependent immune response to Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2141–2149. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00024-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakpour N, Camp L, Smithers HM, Wang B, Tu Z, Nadler SA, Luckhart S. Protein kinase C-dependent signaling controls the midgut epithelial barrier to malaria parasite infection in anopheline mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TM, Gow AJ, Luckhart S. Nitric oxide metabolites induced in Anopheles stephensi control malaria parasite infection. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RE, Looareesuwan S, Molyneuz ME, Hatz C, Warrell DA. Hypoglycaemia and counterregulatory hormone responses in severe falciparum malaria: treatment with Sandostatin. Q J Med. 1993;86:233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietri JE, Cheung KW, Luckhart S. Knockdown of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling in the midgut of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes using antisense morpholinos. Insect Molec Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/imb.12103. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani A, Sharma A, Rajgopal R, Adak T, Bhatnagar RK. Bacterial diversity analysis of larvae and adult midgut microflora using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods in lab-reared and field-collected Anopheles stephensi-an Asian malarial vector. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci I, Damiani C, Scuppa P, Mosca M, Crotti E, Rossi P, et al. The yeast Wickerhamomyces anomalus (Pichia anomala) inhabits the midgut and reproductive system of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:911–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehle MA, Fan Y, Cao C, Brown MR. Molecular characterization of insulin-like peptides in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti: expression, cellular localization, and phylogeny. Peptides. 2006;27:2547–2560. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield L, Hackett F. Signal transduction in host cells by glycosylphosphatidylinositol toxin of malaria parasites. J Exp Med. 1993;177:145–153. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim C, Denlinger DL. A shut-down in expression of an insulin-like peptide, ILP-1, halts ovarian maturation during the overwintering diapause of the mosquito Culex pipiens. Insect Mol Biol. 2009;18:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surachetpong W, Singh N, Cheung KW, Luckhart S. MAPK ERK signaling regulates the TGF-beta1-dependent mosquito response to Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000366. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surachetpong W, Pakpour N, Cheung KW, Luckhart S. Reactive oxygen species-dependent cell signaling regulates the mosquito immune response to Plasmodium falciparum. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;14:943–955. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay S, Rawat M, Adak T, Dixit R, Nanda N, Srivastava H, et al. Parasite killing in malaria non-vector mosquito Anopheles culicifacies species B: implication of nitric oxide synthase upregulation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volohonsky G, Steinert S, Levashina EA. Focusing on complement in the antiparasitic defense of mosquitoes. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gilbreath TM, Kakutla P, Yan G, Xu J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Gulia M, Clark KD, Dhara A, Crim JW, Strand MR, et al. Two insulin-like peptide family members from the mosquito Aedes aegypti exhibit differential biological and receptor binding activities. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;328:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NJ, Warrell DA, Chanthavanich D, Looareesuwan S, Warrell MJ, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:61–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307143090201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report. 2014 http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2014/en.

- Wu Q, Brown MR. Signaling and function of insulin-like peptides in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassine H, Osta MA. Anopheles gambiae innate immunity. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou CG, Tu Q, Niu J, Ji XL, Zhang KQ. The DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor functions as a regulator of epidermal innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003660. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Liu J, Li CR, Momen B, Kohanski RA, Pick L. Deletion of Drosophila insulin-like peptides causes growth defects and metabolic abnormalities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:19617–19622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905083106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cohorts of 30 female A. stephensi were provided either an unsupplemented, P. falciparum-infected blood meal or a P. falciparum-infected blood meal supplemented with the MEK inhibitor UO126 (10 μM; Surachetpong et al., 2009; Selleckchem). Midguts were collected 1 hour after feeding and protein extracts were used for western blotting to detect phosphorylated ERK. Values were normalized to Coomassie brilliant blue stain for total protein with proportional levels indicated below the blots. Protein samples were obtained from a biological replicate in which provision of UO126 inhibited AsILP expression.

Supplementary Table 1. Effects of anti-AsILP morpholino treatment on the prevalence and intensity of P. falciparum in A. stephensi by replicate.