Abstract

Background

Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome (BOS), chronic lung allograft rejection, remains an impediment for the function of the transplanted organ. In this study, we defined the role of MicroRNAs (miRNAs) miR-144 in fibroproliferation leading to BOS.

Methods

Biopsies were obtained from lung transplant (LTx) recipients with BOS (n=20) and without BOS (n=19). Expression of miR-144 and its target, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)-induced factor homeobox 1(TGIF1), were analyzed by real-time PCR and Western blot. Over expression of miR-144 and luciferase reporter genes were performed to elucidate miRNA-target interactions. The function of miR-144 was evaluated by transfecting fibroblasts and determining response to TGFβ by analyzing Sma and Mad Related Family (Smads), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), TGFβ, and Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Smooth Muscle Actin-α-(SMAα) positive stress fibers and F-actin filaments in lung fibroblasts were analyzed by immunofluorescence.

Results

Analysis of miR-144 in the biopsies demonstrated 4.1±0.8 fold increases in BOS+ compared to BOS− with significant reduction in TGIF1(3.6±1.2 fold), a co-repressor of Smads. In vitro transfection confirmed that over expression of miR-144 results in reduction in TGIF1 and increase in Smad2, Smad4, FGF6, TGFβ, and VEGF. Increasing miR-144 by transfecting, increased SMA-α and Fibronectin and knockdown of miR-144 diminished fibrogenesis in MRC-5 fibroblasts.

Conclusions

miR-144 is a critical regulator of the TGFβ signaling cascade and is over expressed in lungs with BOS. Therefore, miR-144 is a potential target towards preventing fibrosis leading to BOS following LTx.

Keywords: lung transplantation, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, microRNA, TGFβ

Introduction

Lung transplantation (LTx) is a therapy for patients with end-stage pulmonary disorders. Unfortunately, chronic lung allograft rejection, clinical correlate Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome (BOS), is a major limitation to long-term allograft survival (1). Approximately 30% and 75% of patients develop BOS by 2.5 and 10 years after transplantation (1). The pathogenesis of BOS involves both alloimmune and non-alloimmune mechanisms. The histological hallmark of chronic rejection is obliterative bronchiolitis (OB), which is an inflammatory/fibrotic process affecting the small non airways, that manifests as fibrosis causing partial or complete luminal occlusion (2, 3). The fibro-obliteration is often associated with destruction of the smooth muscle and elastica of the airway wall (2). Recently, the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) expression has been demonstrated to be increased in BOS LTx recipient (LTxR) even before the onset of obstruction (4, 5). Similarly TGFβ was reported to be associated with histological OB following LTx (6). However, regulation of the TGFβ signaling pathway in lung inflammation and fibrosis after LTx remains unclear.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small regulatory RNAs that control the expression of genes by translational suppression and destabilization of target mRNAs (7). miRNAs have been implicated in multiple biological processes (8). It has been demonstrated that gene specific translational silencing by miRNAs exerted important roles in fibrosis of heart (9, 10), kidney (11), and liver (12). However, the role of miRNAs in fibrogenesis after LTx remains unclear. Recent studies showed that miR-144 was dysregulated during acute rejection after heart and renal transplantations (13, 14). miR-144 was also aberrantly expressed in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (15). The goal of this study is to elucidate the role of miR144 in BOS following human LTx.

Methods

Patient and Sample Collection

Thirty-nine LTxR at Barnes Jewish Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine were enrolled between January 2007 and June 2014 after obtaining informed consent and approval by the Washington University Human Studies Committee. All of LTxR in the BOS+ and BOS− groups were matched for age, time from LTx, type of LTx, and underlying diagnosis. Among them, 20 patients (BOS+ group) had a clinical diagnosis of BOS while the other 19 patients (BOS− group) didn’t develop BOS when sampling (Table 1). The diagnosis of BOS was made by the criteria established by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) (16). The immunosuppressive regimen consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. The biopsy specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were obtained during post-transplant period for routine clinical follow up.

Table 1.

Demographic data and clinical features on BOS+ and BOS− transplant recipients.

| Clinical features | Group 1 (n=19) | Group 2 (n=20) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Groups | BOS− Patients | BOS+ patients |

| Age | 57±10 | 60±12 |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 12 | 11 |

| Female | 7 | 9 |

| Race: | ||

| Caucasian | 18 | 18 |

| African American | 1 | 2 |

| Diagnosis: | ||

| IPF | 10 | 9 |

| COPD | 6 | 5 |

| CF | 3 | 5 |

| Others | 0 | 1 |

| Type of LTx (Bilateral/Single LTx) | ||

| Bilateral LTx | 19 | 20 |

| Single LTx | 0 | 0 |

| Time of Sampling from LTx (months) | 22±9 | 21±6 |

| Time of BOS onset (months) | NA. | 16±7 |

Definition of abbreviations: CF = cystic fibrosis; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LTx = lung transplant.

Quantification of miRNA

Lung biopsies from BOS+ and BOS− LTxR were used for miR-144 quantitative PCR analysis. Total RNA was extracted using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s specification (Ambion, Austin, TX). MicroRNA-144 was further quantified by TaqMan miRNA assays (Applied Biosystems Cat#4427975).

Immunohistochemical staining for TGFβ-induced factor homeobox 1 (TGIF1)

Immunohistochemistry was performed using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded lung biopsy specimens according to the method previously described (17). The primary antibody (Ab) (TGIF1 rabbit polyclonal Abs) was purchased from Abcam, Cambridge, MA.

Cell Culture

The MRC-5 lung fibroblast cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured as recommended by ATCC.

miRNA transfection

miR-144 mimics and inhibitors were purchased from Ambion (mirVana miRNA-144 mimic: MC11051; mirVana miRNA-144 inhibitor: MH11051). MRC5 cells were transfected at 30–40% confluency in 6 well plates using Lipofectamin RNAi MAX™ (Invitrogen Cat#13778) with miRNA mimics and inhibitors at a final concentration of 10 nM.

Plasmids

The 3′ UTR fragment of human TGIF1 was cloned into the luciferase reporter plasmid phRL-TK and the resulting plasmid was termed phRL-TK-TGIF1. To analyze the combination of TGIF1 and miR-144, the sequence of 1st binding site (Position 182–188 of TGIF1 3′ UTR) 5′>TACTGTA <3′ was mutated to 5′>GCTGAGC<3′ by PCR. Similarly, the sequence of 2nd binding site (Position 369–375 of TGIF1 3′ UTR) 5′>ATACTGT<3′ was mutated to 5′>CGCTGAC<3′ by PCR.

Luciferase assay

MRC-5 cells were seeded at 105 cells per well in 12-well plates, then transfected using 10 nM miR-144, 1 ng of phRL-TK-TGIF1 or phRL-TK-mutTGIF1 and 5 ng of firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-control). Luciferase activity was measured 36 hr after transfection by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI).

Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The mRNA expression of human TGIF1, Smad-2,-3,-4,-5 from lung tissues and MRC5 cells was measured by qRT-PCR using gene-specific primers according to the recommendations from IDT. qRT-PCR protocol was done according to earlier publication (18).

Western blotting

Protein from MRC-5 cells transfected with miRNA-144 were subjected to western blot based on the protocol published earlier (19). The primary Abs were anti-TGIF1 (Cell Signaling), anti-Smad-2,-3,-4,-5 (Santa Cruz), anti-SMA-α (Abcam), and anti-Fibronectin (FN) (Abcam) Abs. The secondary Ab conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was purchased from Jackson Immuno Research.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (20). Fibroblasts growing on 20% FBS-pre-coated cover-slides were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 2 min, it was blocked in PBS containing 5% BSA for 1 hr. Cells were then incubated with a mixture of anti-SMA-α and FITC-conjugated phalloidin overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed three times and then incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Texas Red) for 1 hr and mounted with DAPI-containing mounting solution. Fluorescent images were taken with a Zeiss confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microsystems).

Fibrogenic growth factors (FGF) production

The production of FGF6, TGF-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels from supernatants of MRC5 cells was determined by the method of enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) as previously described (17).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM 4.0 (San Diego, CA). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were compared by Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P-value less than 0.05.

Results

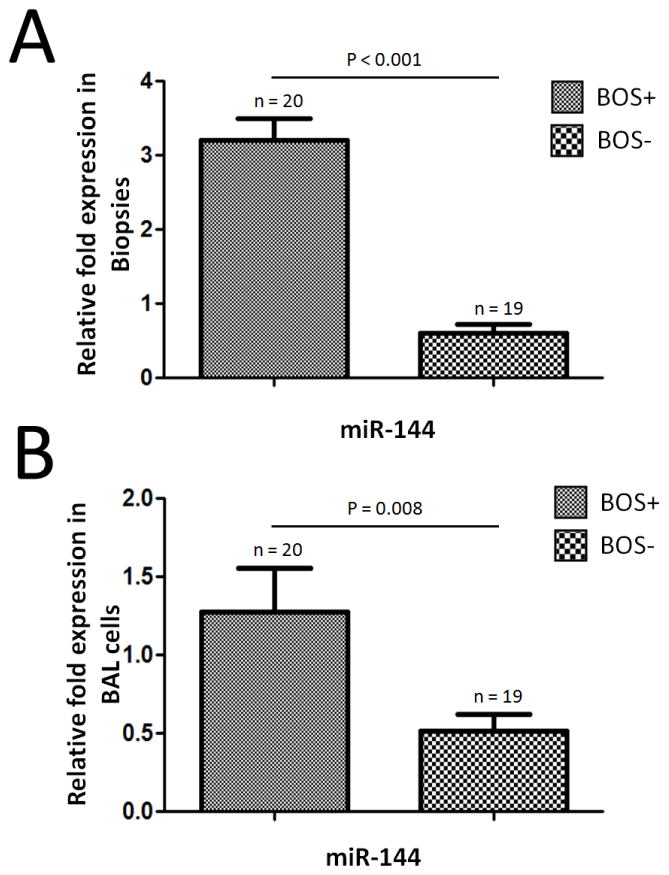

Increased expression of miR-144 in LTxR diagnosed with BOS

To determine the expression of miR-144 in LTx, total RNAs were extracted from biopsies of 20 LTxR with BOS (BOS+) and 19 LTxR without BOS (BOS−). RT-PCR was performed by using TaqMan miRNA kit specific for miR-144. Analysis of the miR-144 in the biopsies demonstrated a 4.1±0.8 fold increase in the level of miR-144 in the BOS+ compared to BOS− samples (p<0.001, Figure 1A). The expression of the housekeeping gene snoRNA135 remained constant. In addition, the level of miR-144 in BAL cells isolated from BOS+ patients was increased compared to that from BOS− patients (p=0.008, Figure 1B), which suggest that miR-144 can be a potential biomarker for BOS. Taken together, these data demonstrated that miR-144 was up regulated in BOS+ LTxR both in lung biopsies as well as in BAL cells and suggest that it may contribute to BOS development following human LTx.

Figure 1.

RT-PCR detection of miR-144 expression in LTxR. (A) The level of miR-144 expression in lung biopsies from BOS+ patients was up regulated as compared with BOS− patients (p < 0.001). (B) The level of miR-144 in BAL cells isolated from BOS+ patients was over expressed compared to that from BOS− patients (p=0.008). Data shown is repeated with three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. RNU48 were used as controls to normalize data.

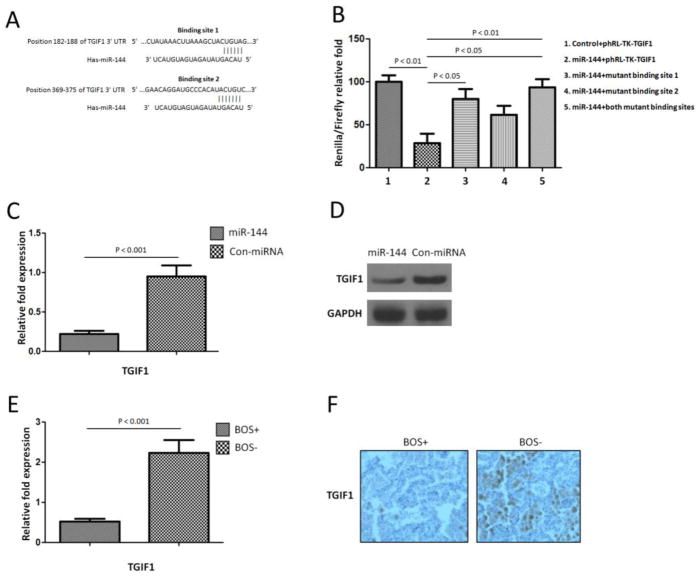

TGIF1 is a target of miR-144 in the lung

To explore the function of miR-144, we determined its target genes using prediction by two computational algorithms (TargetScan and miRanda). The results predicted there were two binding sites of miR-144 to the 3′UTR of TGIF1 (Figure 2A). To determine whether TGIF1 was a direct target of miR-144, fragments of the 3′ UTRs of TGIF1 containing wild-type or mutated miR-144 complementary sites were cloned into the phRL-TK renilla luciferase reporter plasmid. Luciferase reporters were co-transfected with miRNA mimic of miR-144 into MRC-5 lung fibroblast cells (Figure 2B). We then examined binding of human miR-144 to the 3′UTR of TGIF1 mRNA using a luciferase assay. As the 3′UTR of TGIF1 is inserted downstream of the luciferase open reading frame, specific binding to miR-144 prevents luciferase reporter gene expression (Figure 2B). In addition, mutations of both TGIF1 binding sites decreased specific binding to miR-144 and restored luciferase activity (Figure 2B) indicating that TGIF1 is indeed a target of miR-144. These results demonstrated that over expression of miR-144 in lung fibroblasts results in significant reduction in the levels of TGIF1. Therefore, miR-144 can regulate lung fibrosis via TGFβ signal pathway following human LTx.

Figure 2.

TGIF1 is a target of miR-144 in the lung. (A) The miR-144 binding site predictions for TGIF1 3′ untranslated region (UTR) by microRNA.org. Mutations of the seed region of two binding sites were inserted by site-directed mutagenesis. (B) Relative luciferase activities in transiently transfected MRC-5 lung fibroblast cells (1x105 cells in triplicate) were measured using TGIF1 renilla luciferase reporters and a constitutive Firefly luciferase reporter pGL3. After 48 hours of co-transfection with controls miRNA mimics and pre-miR-144. Renilla luciferase activity was normalized to the Firefly luciferase activity. Data shown is repeated with three independent experiments and represented as mean ± SEM and were compared by Student t test. (C) Real-time RT-PCR detection of TGIF1 expression in lung fibroblast cells transfected with miR-144 as compared with control miR-transfected lung fibroblast cells (P < 0.01). Data shown is repeated with three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. GAPDH were used as controls to normalize data. (D) Western blot assay demonstrated that TGIF1 protein level was down regulated when over expression of miR-144 in MRC-5 cells. GAPDH were used as loading control. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments. (E) RT-PCR detection of TGIF1 expression in LTxR. Down-regulated miR-144 expression in BOS+ patients as compared with BOS− patients (P<0.001). Data shown is repeated with three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. GAPDH were used as controls to normalize data. (F) Immunohistochemical staining of TGIF1 was performed using lung biopsy tissues from BOS+ and BOS− patients. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments. Original magnification, x 400

To determine that over expression of miR-144 will result in the decrease of TGIF1, we overexpressed miR-144 in MRC-5 lung fibroblast cells. qRT-PCR demonstrated that TGIF1 expression was down-regulated in MRC-5 fibroblast cells transfected with miR-144 as compared with control-transfected cells (4.6±0.7 fold p<0.001, Figure 2C) indicating that miR-144 mediated transcriptional regulation of TGIF1 expression resulted in marked decrease in TGIFI. In addition, western blot demonstrated that TGIF1 protein level was down regulated following over expression of miR-144 in MRC-5 cells (Figure 2D). We further identified that the level of TGIF1 was 3.6±1.2 fold lower in the BOS+ compared to BOS− samples (p<0.001, Figure 2E). Immunohistochemical staining of TGIF1 in lung biopsy tissues from BOS+ and BOS− patients demonstrated that out of 20 BOS+ LTxR 18 (90%) were completely TGIF1 negative. In contrast, all of the 19 (100%) BOS− patients were TGIF1 positive (Figure 2F). These results demonstrate that an increase in miR-144 noted in LTx biopsies from BOS+ patients can down regulate TGIF1 thereby increasing TGFβ secretion leading to increased fibrosis.

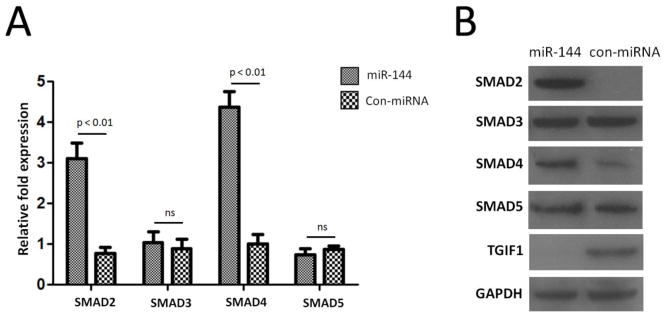

Over expression of miR-144 increases Smad levels

TGIF1 was reported to act as a corepressor of Smad and an inhibitor of the retinoic acid responsive element (21, 22) and they are implicated in the development of fibrosis and Th17 responses (23, 24). Therefore, we performed in vitro transfection analysis of MRC-5 cells using miR-144 mimics. The results demonstrated that over expression of miR-144 results in significant increase in the expression of Smad2 (p<0.01, 4.3±0.8 fold) and Smad4 (p<0.01, 4.1±0.4 fold) compared to control-transfected fibroblasts (Figure 3A), However, there were no significant changes of Smad3 and Smad5 between miR-144 transfected fibroblasts and control-transfected fibroblasts (Figure 3A). In addition, western blot demonstrated that both Smad2 and Smad4 protein levels were up regulated following over expression of miR-144 in MRC-5 cells (Figure 3B). These data indicated that increased levels of miR144 in lung fibroblast results through increased activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway.

Figure 3.

Over expression of miR-144 increase SMADs levels. (A) Real-time RT-PCR detection of SMAD levels. SMAD2, SMAD3, SMAD4, and SMAD5 expression in lung fibroblast cells transfected with miR-144 as compared with control-transfected lung fibroblast cells. Data shown is repeated with three independent experiments and represented as mean ± SEM. GAPDH were used as controls to normalize data. (B) Western blot assay of SMADs protein levels when over expression of miR-144 in MRC-5 cells. GAPDH were used as loading control. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments.

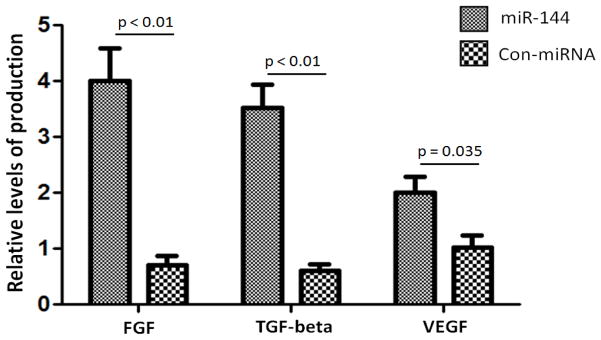

Over expression of miR-144 increases growth factor production

In order to determine whether miR-144 can induce the production of FGF by lung fibroblasts, we performed in vitro bioassay for FGF, TGFβ and VEGF following transfection of MRC-5 cells with miR-144.. As shown in Figure 4, over expression of miR-144 in MRC-5 lung fibroblasts produced significantly higher levels of FGF6 (p<0.01, 4.1±0.9), TGFβ (p<0.01, 3.5±0.6) and VEGF (p=0.035, 1.7±0.4) as compared to control-transfected cells (Figure 4). These results demonstrated that over expression of miR-144 in lung fibroblasts results in the production of FGF6, TGFβ, and VEGF, which can lead to increased fibrosis leading to BOS after LTx.

Figure 4.

Over expression of miR-144 increases growth factor production. FGF6, TGF-β and VEGF production in lung fibroblast cells transfected with miR-144 as compared with control-transfected lung fibroblast cells. Data shown is repeated with three independent experiments and represented as mean ± SEM.

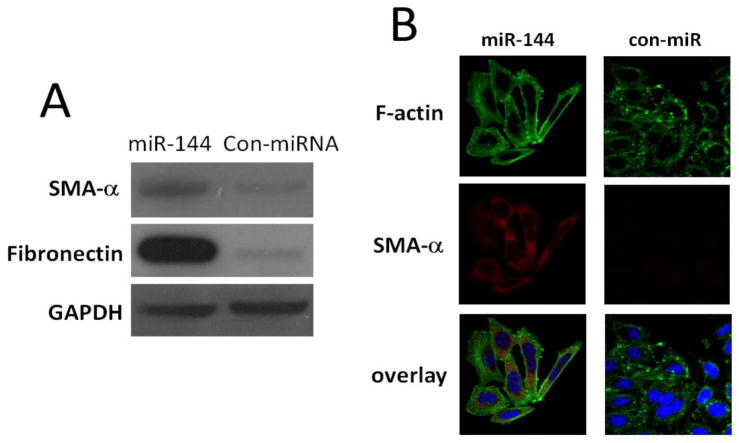

MiR-144 regulates fibrogenesis in lung fibroblasts

We next determined whether miR-144 regulates fibrogenesis in human lung fibroblasts. It has been demonstrated that alpha-SMA is the actin isoform that predominates within vascular smooth-muscle cells and plays an important role in organ fibrogenesis including lungs (25) and kidneys (26). Filamentous actin (F-actin) is another biomarker of pulmonary fibrosis (27). Therefore, we chose alpha-SMA and F-actin as the read out for fibrosis. As shown in Figure 5A, increasing miR-144 levels in fibroblasts by transfecting miR-144 mimics increased protein expression of SMA-α and FN compared to those in control miR-transfected MRC-5 cells (Figure 5A). These data suggest that miR-144 will increases the fibrogenic activity. Immunofluorescence analysis also demonstrated that over expression of miR-144 increases SMA-α-positive stress fibers, which overlapped with long filamentous F-actin (Figure 5B). Therefore, miR-144 enhances SMA-α-positive stress fibers and produced higher F-actin filaments in lung fibroblasts (Figure 5B). These data indicate that miR-144 functionally regulate lung fibroblast fibrogenesis.

Figure 5.

Over expression of miR-144 increases fibrogenesis in lung firboblasts. (A) Normal lung fibroblast MRC-5 cells were transfected with 10 nM control mimics (con-miR) or 10 nM miR-144 mimics. At 2 days after the transfection, levels of SMA-α, FN, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Data are from three independent experiments. (B) Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics or miR-144 mimics. Alpha-SMA and F-actin were chosen to evaluate fibrogenesis as the biomarkers. At 2 days after the transfection, cells were then fixed and incubated with a mixture of anti-SMA-α antibody and FITC-conjugated phalloidin for staining of F-actin overnight. After washing 3 times, cells were incubated with Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Texas Red) for 1 h. Confocal microscopy was performed. Representative experiments are shown. Original view: ×63.

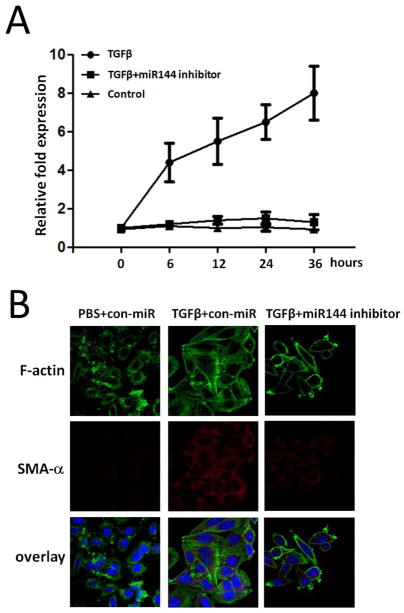

Knockdown of miR-144 diminishes fibrogenesis in lung fibroblasts

To address the expression pattern of miR-144 in more detail, we used qRT-PCR to assess miR-144 expression in a time dependent manner after TGFβ treatment in lung fibroblasts. There was significantly higher level of miR-144 expression after 6 hrs of TGFβ stimulation than seen in control group and miR-144 levels increased in a time dependent manner up to 36 hours (Figure 6A). However, miR-144 was significantly down regulated from 0 hour to 36 hours in miR-144 inhibitor transfected cells (Figure 6A). To further characterize the role of miR-144 in regulating fibrogenesis, we knocked down miR-144 in lung fibroblasts and found that TGFβ up-regulated expression of SMA-α and F-actin was significantly diminished in anti-miR-144-transfected cells (Figure 6B). These data suggest that decreased miR-144 expression in the lungs could block pulmonary fibrosis through decreasing fibrogenic activity.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of miR144 diminishes fibrogenesis in lung fibroblasts. (A) TaqMan RT-PCR analysis of miR-144 expression under 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 hours treatment after TGF-β stimulation in lung fibrobalsts transfected with miR-144 inhibitor or control miR inhibitors. (B) Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 20 nM control inhibitors (con-anti-miR) or 20 nM inhibitors to miR-144 (anti-miR-144). Alpha-SMA and F-actin were chosen to evaluate fibrogenesis as the biomarkers. At 1 day after the transfection, cells were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 1 day, followed by treatment without or with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 1 d. Cells were then fixed and incubated with a mixture of anti-SMA-α antibody and FITC-conjugated phalloidin for staining of F-actin overnight. After washing 3 times, cells were incubated with Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Texas Red) for 1 h. Confocal microscopy was performed. Representative experiments are shown. Original view: ×63.

Discussion

miRNAs are known to regulate numerous physiological processes (28). Dysregulation of miRNA expression has been demonstrated to participate in the development of BOS after LTx (29). However, the role of miRNAs which may contribute to the development of fibroproliferative cascades in LTxR remains unknown. Recent studies have implicated miRNAs in pulmonary fibrosis and regulation of TGFβ signaling (30). Pandit et al reported that miRNA let-7d was decreased in experimental lung fibrosis and human Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (31). In particular, let-7d was down regulated by TGFβ1 and inhibition of let-7d resulted in differential expression of mesenchymal and epithelial cell markers in alveolar epithelial type II cells (31). Liu et al demonstrated that miR-21 was involved in TGFβ1-induced fibroblast activation via interference with Smad signaling (25). Other studies have implicated miR-29 in promoting fibrinogenesis by increasing TGFβ via Smad3 signaling (32). A significant down-regulation of miR-200 has also been reported in bleomycin-induced fibrosis and in patients with IPF, proposing that the miR200 family may regulate TGFβ-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells (33). In our current study, we demonstrate that increased level of miR-144 in BOS+ patients result in increased activation of the TGFβ/Smad signaling cascade leading to increased fibrogenic processes. We further demonstrate that in vivo transfection of lung fibroblast cell line MRC-5 with miR-144 increases expression of SMA-α and FN. These data are of significance because it suggests that attenuation of miR-144 expression may be able to reverse the intrinsically acquired pathological phenotypes of fibroblasts in transplanted lungs during the development of BOS.

TGFβ1 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis by enhancing the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activity of lung fibroblasts (34, 35). Increased TGFβ activity have been detected in lung tissue from bleomycin-treated mice (36) and patients with IPF (37). Over expression of active TGFβ in the mouse lung in vivo results in severe interstitial and pleural fibrosis (38). Analysis of Smad3-deficient mice indicated that bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis is partially dependent on the integrity of the TGFβ pathway (39). In response to TGFβ signaling, Smad2 and Smad3 are phosphorylated directly by the TGFβ receptor, then complexed with Smad4, and translocated to the nucleus (40, 41). After TGFβ stimulation, Smad proteins enter the nucleus and form transcriptional activation complexes or interact with TGIF1, which functions as a corepressor (21, 42, 43). The relative levels of Smad co-repressors and co-activators present within the cell may determine the outcome of a TGFβ response. Results presented in the current study, for the first time demonstrate that miR-144 levels are increased and TGIF1 levels are decreased in LTxR diagnosed with BOS. Using in vitro experiments with lung fibroblast cell line MRC-5 we determined and validated that over expression of miR-144 results in down regulation of TGIF1 and increased expression of Smad2, Smad4 and fibrogenic growth factors. Taken together, we present evidence that dysregulated miRNA in TGFβ signal pathway is important in inducing lung fibrinogenesis leading to BOS following human LTx and miR-144 may participate significantly in the immunopathogenesis of BOS.

There are some limitations in this study including the fact that the evidence for a potential role of miR-144 leading to dysregulation of TGFβ signal pathway is primarily derived from clinical samples of LTxR diagnosed with BOS. Although we have confirmed its role using in vitro experiments with human lung fibroblast cell line, In vivo experiments that involve perturbations of miR-144 expression in animal models of fibrosis are required to prove its central profibrotic role. Another limitation is that the target prediction of miR-144 demonstrated many other potential targets. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of other potential targets for miR-144 that may have an impact on fibroproliferative cascades after LTx.

In summary, results presented in this report demonstrate a critical role for miR-144 in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis leading to BOS following human LTx. Using in vitro studies with human lung fibroblasts we also demonstrated that knock down of miR-144 expression significantly diminishes fibrogenic activity of lung fibroblasts through attenuation of the expression of SMA-α and FN. Therefore, we propose that miR-144 may be a novel therapeutic target for preventing pulmonary fibrosis leading to BOS following human LTx.

Footnotes

Disclosures statement Human Lung and BJC

Funding for these studies was provided by the National Institutes of Health grant RO1 HL056643-13 (TM) and the BJC Foundation (TM). We thank Billie Glasscock for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of the presented manuscript or other conflicts of interest to disclosure.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Aurora P, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-sixth Official Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report-2009. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:1031–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart S, Fishbein MC, Snell GI, et al. Revision of the 1996 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of lung rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:1229–42. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yousem SA, Berry GJ, Cagle PT, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the classification of pulmonary allograft rejection: Lung Rejection Study Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charpin JM, Valcke J, Kettaneh L, Epardeau B, Stern M, Israel-Biet D. Peaks of transforming growth factor-beta mRNA in alveolar cells of lung transplant recipients as an early marker of chronic rejection. Transplantation. 1998;65:752–5. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199803150-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnan A, Mege JL, Escallier JC, et al. Balance between alveolar macrophage IL-6 and TGF-beta in lung-transplant recipients. Marseille and Montreal Lung Transplantation Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1431–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.4.8616577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Gamel A, Sim E, Hasleton P, et al. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) and obliterative bronchiolitis following pulmonary transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:828–37. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stefani G, Slack FJ. Small non-coding RNAs in animal development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:219–30. doi: 10.1038/nrm2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taft RJ, Pang KC, Mercer TR, Dinger M, Mattick JS. Non-coding RNAs: regulators of disease. J Pathol; 220:126–39. doi: 10.1002/path.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456:980–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE, et al. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13027–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung AC, Huang XR, Meng X, Lan HY. miR-192 mediates TGF-beta/Smad3-driven renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol; 21:1317–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu AS, Friedman JR. A role for microRNA in cystic liver and kidney diseases. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3585–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI36870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukma Dewi I, Torngren K, Gidlof O, Kornhall B, Ohman J. Altered serum miRNA profiles during acute rejection after heart transplantation: potential for non-invasive allograft surveillance. J Heart Lung Transplant; 32:463–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sui W, Dai Y, Huang Y, Lan H, Yan Q, Huang H. Microarray analysis of MicroRNA expression in acute rejection after renal transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2008;19:81–5. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie T, Liang J, Guo R, Liu N, Noble PW, Jiang D. Comprehensive microRNA analysis in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis identifies multiple sites of molecular regulation. Physiol Genomics; 43:479–87. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00222.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:297–310. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golocheikine A, Nath DS, Basha HI, et al. Increased erythrocyte C4D is associated with known alloantibody and autoantibody markers of antibody-mediated rejection in human lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant; 29:410–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shenoy S, Mohanakumar T, Todd G, et al. Immune reconstitution following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:335–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goers TA, Ramachandran S, Aloush A, Trulock E, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T. De novo production of K-alpha1 tubulin-specific antibodies: role in chronic lung allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2008;180:4487–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu G, Park YJ, Abraham E. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) -1-mediated NF-kappaB activation requires cytosolic and nuclear activity. Faseb J. 2008;22:2285–96. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-101816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wotton D, Knoepfler PS, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Massague J. The Smad transcriptional corepressor TGIF recruits mSin3. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:457–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartholin L, Powers SE, Melhuish TA, Lasse S, Weinstein M, Wotton D. TGIF inhibits retinoid signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:990–1001. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.990-1001.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. Faseb J. 2004;18:816–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra N, Robertson E, Kang J. SMAD2 is essential for TGF beta-mediated Th17 cell generation. J Biol Chem; 285:29044–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.156745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Friggeri A, Yang Y, et al. miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J Exp Med; 207:1589–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boukhalfa G, Desmouliere A, Rondeau E, Gabbiani G, Sraer JD. Relationship between alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and fibrotic changes in human kidney. Exp Nephrol. 1996;4:241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolker-Nielsen T, Hoiby N. Extracellular DNA and F-actin as targets in antibiofilm cystic fibrosis therapy. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:645–7. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dey BK, Mueller AC, Dutta A. Long non-coding RNAs as emerging regulators of differentiation, development, and disease. Transcription. 5:e944014. doi: 10.4161/21541272.2014.944014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang W, Zhou T, Ma SF, Machado RF, Bhorade SM, Garcia JG. MicroRNAs Implicated in Dysregulation of Gene Expression Following Human Lung Transplantation. Transl Respir Med. 1 doi: 10.1186/2213-0802-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandit KV, Milosevic J, Kaminski N. MicroRNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res; 157:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandit KV, Corcoran D, Yousef H, et al. Inhibition and role of let-7d in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med; 182:220–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1698OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou L, Wang L, Lu L, Jiang P, Sun H, Wang H. Inhibition of miR-29 by TGF-beta-Smad3 signaling through dual mechanisms promotes transdifferentiation of mouse myoblasts into myofibroblasts. PLoS One. 7:e33766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang S, Banerjee S, de Freitas A, et al. Participation of miR-200 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol; 180:484–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang HR, Cho SJ, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Elias JA. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 stimulates pulmonary fibrosis and inflammation via a Bax-dependent, bid-activated pathway that involves matrix metalloproteinase-12. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7723–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheppard D. Transforming growth factor beta: a central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:413–7. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-008AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raghow B, Irish P, Kang AH. Coordinate regulation of transforming growth factor beta gene expression and cell proliferation in hamster lungs undergoing bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1836–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI114369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broekelmann TJ, Limper AH, Colby TV, McDonald JA. Transforming growth factor beta 1 is present at sites of extracellular matrix gene expression in human pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:6642–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sime PJ, Xing Z, Graham FL, Csaky KG, Gauldie J. Adenovector-mediated gene transfer of active transforming growth factor-beta1 induces prolonged severe fibrosis in rat lung. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:768–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI119590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao J, Shi W, Wang YL, et al. Smad3 deficiency attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L585–93. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00151.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen YG, Hata A, Lo RS, et al. Determinants of specificity in TGF-beta signal transduction. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2144–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wotton D, Lo RS, Swaby LA, Massague J. Multiple modes of repression by the Smad transcriptional corepressor TGIF. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37105–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wotton D, Lo RS, Lee S, Massague J. A Smad transcriptional corepressor. Cell. 1999;97:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]