Abstract

Background

Despite limited research, some evidence suggests that examining substance use at multiple levels may be of greater utility in predicting sexual behavior than utilizing one level of measurement, particularly when investigating different substances simultaneously. We aimed to examine aggregated and event-level associations between three forms of substance use—alcohol, marijuana, and club drugs—and two sexual behavior outcomes—sexual engagement and condomless anal sex (CAS).

Method

Analyses focused on both 6-week timeline follow-back (TLFB; retrospective) and 30-day daily diary (prospective) data among a demographically diverse sample of 371 highly sexually active HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual men.

Results

Models from both TLFB and diary showed that event-level use of alcohol, marijuana, and club drugs was associated with increased sexual engagement, while higher aggregated frequency marijuana and any frequency club drug use were associated with decreased sexual engagement. Event-level use of club drugs was consistently associated with increased odds of CAS across both TLFB and diary models while higher frequency marijuana use was most consistently associated with a lower odds of CAS.

Conclusions

Findings indicated that results are largely consistent between retrospective and prospective data, but that retrospective results for substance use and sexual engagement were generally greater in magnitude. These results suggest that substance use primarily acts to increase sexual risk at the event-level and less so through individual-level frequency of use; moreover, it primarily does so by increasing the likelihood of sex on a given day with fewer significant associations with the odds of CAS on sex days.

Keywords: substance use, sexual behavior, gay and bisexual men, daily diary, timeline follow-back, multilevel modeling

1. INTRODUCTION

A large body of literature has emerged in recent decades examining the influence of substance use on sexual risk-taking—particularly among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), who remain disproportionately affected by HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). One potential influence contributing to the elevated risk of HIV infection among GBMSM is substance use (Koblin et al., 2006). Numerous reviews have provided evidence for this association (Drumright et al., 2006b; Halpern-Felsher et al., 1996; Leigh and Stall, 1993; Vosburgh et al., 2012), but inconsistencies in the operationalization of substance use and sexual behavior—particularly regarding types of substance and sexual behaviors as well as the level of analysis—have limited researchers’ ability to reliably predict this association.

Studies have traditionally examined this association using one of two levels of analysis (Leigh and Stall, 1993). Aggregate or global association studies typically examine the overall frequency of substance use and overall frequency of sexual behavior over a specified time period (Drumright et al., 2006b; Leigh and Stall, 1993; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2013; Shuper et al., 2009). In contrast, event-level analyses examine substance use and sexual events as each occurs using repeated measurements (e.g., daily diaries, ecological momentary assessment) over time, capturing not only their relative frequency but also their co-occurrence (Parsons et al., 2013a, 2013b). Given the ability to examine co-occurrence, there is a preference for event-level analyses in providing greater support for causal hypotheses. By nature of their designs, these two types of data answer somewhat different questions.

Global studies of aggregated substance use tend toward between-person comparisons focused on differences among users and non-users or the amount of use compared with others. In contrast, event-level studies tend toward within-person comparisons, examining individuals’ behaviors on days on which they had and had not used substances. Global association studies typically suggest a positive association between aggregate substance use and sexual risk behaviors in the general population (Leigh and Stall, 1993) as well as among GBMSM, with positive associations found between condomless anal sex (CAS) and frequent alcohol use (Morin et al., 2005; Tawk et al., 2004), heavy alcohol use (Colfax et al., 2004; Koblin et al., 2003; Woody et al., 1999), and any use of marijuana (Koblin et al., 2003) or club drugs, including cocaine, MDMA/ecstasy, methamphetamine, GHB, and ketamine (Colfax et al., 2005; Drumright et al., 2006b; Klitzman et al., 2002; Koblin et al., 2003; Purcell et al., 2001, 2005; Rusch et al., 2004; Woody et al., 1999). In addition to increased risk of CAS, recent studies continue to support associations between global alcohol and drug use and an increased number of sexual partners (Greenwood et al., 2001; Klitzman et al., 2002; Pollock et al., 2012). For example, Klitzman and colleagues found that, compared to low frequency MDMA users, higher frequency MDMA users had more sex partners and more “one night stands” (Klitzman et al., 2002). Although much of the literature on global alcohol consumption suggests a linear relationship with CAS among GBMSM, some evidence suggests that high levels of club drug use may be associated with lower risk of CAS compared to moderate users (Colfax et al., 2005).

Prior to the mid-1990s, event-level research tended toward examining associations between alcohol and sexual risk (Leigh and Stall, 1993), with more recent research including event-level associations of other substances, though results have been mixed (Leigh, 2002; Leigh and Stall, 1993; Weinhardt and Carey, 2000). For example, a meta-analysis of event-level alcohol consumption and condom use revealed a significant amount of heterogeneity across studies, with findings suggesting a slightly higher odds of condomless sex after drinking (Leigh, 2002). More recent event-level research continues to find mixed results, as demonstrated in recent reviews of event-level studies among GBMSM (Vosburgh et al., 2012; Woolf and Maisto, 2009). These reviews revealed inconsistent findings for non-binge alcohol use (Vosburgh et al., 2012; Woolf and Maisto, 2009), some club drugs, and marijuana (Vosburgh et al., 2012). The most consistent associations with CAS were found for heavy alcohol consumption (i.e., five or more drinks for men; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2004) and methamphetamine use (Vosburgh et al., 2012). Overall, these reviews suggest some forms of event-level substance use in the context of sexual behavior are associated with increased risk for CAS though, as mentioned previously, findings have been inconsistent.

Several potential reasons exist for the observed discrepancies in the literature, including the type of substance investigated, the method of data collection (e.g., retrospective, prospective), the method of assessment (e.g., overall frequency, TLFB), characteristics of the sample, specification of the drug use and sex variables (e.g., any use/behavior, frequency of use/behavior, severity of use/risk of behavior), and the type of analysis performed. Some evidence suggests that examining substance use at multiple levels may be of greater utility in predicting sexual risk behaviors compared to utilizing a single level of measurement (Rusch et al., 2004) and that adjusting for aggregate substance use may reveal consistent associations with sexual behavior across levels of measurement (Colfax et al., 2004). As such, one potential method to alleviate the discrepancies found in the literature is to simultaneously examine both aggregate global substance use and event-level use within the same models, though this type of analysis is underrepresented in the literature to date with a few exceptions (Arasteh et al., 2008; Colfax et al., 2004; Cooper, 2002; Corbin and Fromme, 2002; Purcell et al., 2005; Shuper et al., 2009). In one study examining both levels simultaneously, researchers found a positive association between event-level alcohol consumption and condomless sex but no effect for aggregate global level alcohol use among college students during their first sexual encounter (Corbin and Fromme, 2002). In contrast, a study of GBMSM found heavy alcohol use as well as amphetamine, cocaine, and amyl nitrate (i.e., poppers) use at the global level were positively associated with serodiscordant CAS and, at the event-level, both heavy alcohol consumption and any use of drugs before or during sex were positively associated with increased risk of serodiscordant CAS (Colfax et al., 2004).

In addition to demonstrating the importance of carefully operationalizing the type of substance and sexual behavior being examined and investigating multiple levels of influence simultaneously, previous research has also called for the use of standardized and detailed measures of substance use and sexual risk (Vosburgh, 2012). Both time-line follow back (TLFB) and daily diary data collection methods have become increasingly popular for assessing event-level substance use and sexual behavior, though some evidence from studies on smokers suggests that TLFB and daily diary data may only be moderately correlated (Griffith et al., 2009; Shiffman, 2009).

Given the challenges identified in the literature to date, the aim of this study was to examine both aggregate and event-level associations between substance use and sexual behavior simultaneously. In doing so, we examined three different forms of substance use—alcohol, marijuana, and club drugs—and two sexual behavior outcomes—daily sexual engagement and, among days in which sex occurs, CAS. Moreover, we compared the same models from both a retrospective behavioral interview (i.e., TLFB) and a prospective online daily diary. We conducted these analyses using a sample of HIV-negative and HIV-positive highly sexually active gay and bisexual men (GBM). Evidence suggests that more frequent sexual activity is associated with increased risk of CAS (Prestage et al., 2009), yet the influence of substance use on sexual risk among GBM who are highly sexually active has not been thoroughly examined. As such, these men may be particularly vulnerable to HIV transmission when using alcohol or drugs and make an ideal target for investigation of this topic.

2. METHOD

Analyses for this paper were conducted on data from Pillow Talk, a study of highly sexually active GBM in New York City (NYC). Of the 376 men who enrolled in the project, four completed no daily diaries and one provided insufficient demographic data for inclusion in analyses, resulting in an analytic sample of 371 men. All 371 men in this sample provided a complete 42-day, retrospective TLFB interview, and as such the TLFB analyses focus on a sample of 15,582 days. Participants opened and provided some data for 8,409 prospective daily diary entries, from which 8,238 (98.0%) contained sufficient data for the present analyses, resulting in a median completion rate of 83%. Due to technical error, 101 days’ (1.2%) worth of data on alcohol consumption were randomly missing across 41 participants’ diary reports, and as such the final analytic sample for diary analyses consists of 8,137 days.

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Potential participants completed a phone-based screening interview to assess eligibility, which are described elsewhere (see Parsons et al., 2013c). Participants who met preliminary eligibility completed an Internet-based computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) at home, followed by an in-person baseline appointment. The data for this paper were collected as part of the retrospective TLFB interview conducted in the office at baseline as well as a 30-day prospective online daily diary beginning the day after the baseline appointment. Participants received a unique link to complete their diaries each night starting on the first day following their baseline appointment and continuing for 30 days. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York.

2.2. Measures

Within the CASI from home prior to the baseline appointment, participants reported demographic characteristics, including sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, education, and relationship status.

2.2.1. Timeline follow-back interview

Participants completed a retrospective TLFB interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1992, 1992b) at baseline for the 6-weeks (i.e., 42 days) prior. Using a computerized TLFB calendar, a research assistant coded for whether any substance use or sexual activity occurred on a given day. On days when substance use occurred, the type of drug (i.e., marijuana, ketamine, MDMA/ecstasy, GHB, cocaine/crack, or methamphetamine) and the presence of heavy drinking (i.e., five or more alcoholic drinks) were coded. On days when sex occurred, detailed behavior was recorded for each sex partner, including the types of sexual behavior with that partner (e.g., oral sex, anal sex with and without a condom).

For each day, we created three dichotomous indicators of whether the participant had engaged in: (1) heavy drinking, (2) marijuana use, or (3) club drug use (i.e., ketamine, MDMA/ecstasy, GHB, cocaine/crack, or methamphetamine)—these variables were used as event-level (i.e., Level 1) indicators of substance use within models of the TLFB data.

We also aggregated the three daily substance use indicators above to the individual level to serve as global frequency variables of each substance. Because the sample contained a large proportion of non-users of each substance (43% for heavy drinking, 50% for marijuana, and 63% for club drugs) and because we suspected possible non-linearity in the association between usage frequency and sexual behavior, we recoded these variables into trichotomous categorical variables, consistent with prior research (Colfax et al., 2004). Specifically, for each of the three substances the variables indicated that they were non-users or, among users, lower or heavier frequency users based on a median split. These variables were used as indicators of aggregated (i.e., Level 2) frequency of use in both TLFB and daily diary models (see 2.2.2.).

Because substance use is a day-level variable, for the purposes of this manuscript, partner-level sexual behavior data was aggregated to the day level. Specifically, we created two variables to be used as the outcomes within models focused on the TLFB data: (1) a dichotomous indicator of whether any sexual activity with a casual partner occurred that day and (2) a trichotomous indicator of whether the participant engaged in no sex, sexual activity without CAS (e.g., mutual masturbation, oral sex, anal sex with a condom), or sexual activity with CAS that day. These variables were used as the outcomes of the models focused on TLFB data. For the purposes of demonstration within descriptive analyses (i.e., Table 2), we also calculated an individual-level dichotomous indicator of whether or not each participant had engaged in any CAS over the course of the TLFB as well as the number of times the participant engaged in CAS during the 42-day TLFB. We focused exclusively on casual sexual behavior as a result of the low number of partnered men in the sample, the high number of casual partners for all participants, and the different role that substance use is likely to play in influencing sex with main versus casual partners.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between individual-level frequency of substance use and individual-level CAS.

| Heavy Drinking

|

χ2 (2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Use (n = 158)

|

Lower Frequency (n = 94)

|

Higher Frequency (n = 119)

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Any CAS in TLFB | 106 | 67.1 | 68 | 72.3 | 78 | 65.5 | 1.20, p = 0.55 |

| Any CAS in Diary | 90 | 57.0 | 57 | 60.6 | 65 | 54.6 | 0.78, p = 0.68 |

| Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | H(2) | |

|

|

|||||||

| # CAS Acts in TLFB | 3.0 | 0, 8 | 1.0 | 0, 5 | 1.0 | 0, 5 | 4.92, p = 0.09 |

| Marijuana

|

χ2 (2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Use (n = 185)

|

Lower Frequency (n = 91)

|

Higher Frequency (n = 95)

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Any CAS in TLFB | 118 | 63.8 | 69 | 75.8 | 65 | 68.4 | 4.07, p = 0.13 |

| Any CAS in Diary | 106 | 57.3 | 58 | 63.7 | 48 | 50.5 | 3.32, p = 0.19 |

| Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | H(2) | |

|

|

|||||||

| # CAS Acts in TLFB | 1.0 | 0, 5 | 3.0 | 0, 7 | 2.0 | 0, 5 | 4.17, p = 0.12 |

| Club drugs

|

χ2 (2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Use (n = 235)

|

Lower Frequency (n = 66)

|

Higher Frequency (n = 70)

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Any CAS in TLFB | 150 | 63.8 | 47 | 71.2 | 55 | 78.6 | 5.78, p = 0.06 |

| Any CAS in Diary | 136 | 57.9 | 32 | 48.5 | 44 | 62.9 | 3.01, p = 0.22 |

| Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | H(2) | |

|

|

|||||||

| # CAS Acts in TLFB | 1.0 | 0, 5 | 2.0 | 0, 5 | 4.0 | 1, 11 | 11.51, p = 0.003 |

Note: Number of CAS acts was compared using a Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test (medians presented for interpretability). Number of acts from the diary was not computed due to inability to account for missing diary data when aggregating.

2.2.2. Daily diary

The diary measure was based on previous studies conducted with GBM (Grov et al., 2010; Mustanski, 2007, 2007b). Each day, participants reported on their substance use and, consistent with the TLFB data, we calculated three dichotomous indicators of whether the participant had engaged in heavy drinking, used marijuana, or used club drugs each day. These variables were used as the event-level (i.e., Level 1) substance use predictors in models of the daily diary data. Following those sections, participants were asked whether they had engaged in any sexual activity with another person and, if so, were asked a series of questions for each partner they reported for that day. Consistent with the TLFB data, we recoded all of the casual partner-level data into two day-level variables: (1) a dichotomous indicator of sexual engagement and (2) a trichotomous variable indicating whether the participant engaged in no sex, sexual activity without CAS, or sexual activity with CAS, each focused only on casual partners for that day. These two variables were used as the outcomes within models focused on daily diary data. For the purposes of demonstration within descriptive analyses (i.e., Table 2), we also calculated an individual-level dichotomous indicator of whether or not each participant had engaged in any CAS over the course of the daily diary. There are inherent problems with aggregating daily diary data due to unbalanced number of reports resulting from missing data, and thus we used the frequency of substance use variables from the TLFB as the aggregate-level (i.e., Level 2) predictors within the models of the daily diary.

2.3. Data Analysis

We began by utilizing descriptive statistics to characterize the demographic makeup of the sample. Next, we examined the correspondence between the aggregate-level frequency of substance use variables (i.e., heavy drinking, marijuana, and club drugs) from the TLFB and the individual-level indicators of whether or not participants reported any CAS with casual partners over the course of the 42-day TLFB and 30-day diary cycles utilizing Chi-square statistics as well as the number of CAS acts from the TLFB using Kruskal-Wallis tests.

We next ran a series of multilevel models, with event-level dichotomous indicators of heavy drinking, marijuana, and club drugs at Level 1 and individual-level aggregated frequency of use for each substance as a trichotomous variable (lower and heavier frequency versus non-use as the referent group) at Level 2. For the first outcome—whether or not participants engaged in any sexual activity on a given day—we utilized a binary logistic outcome for TLFB (Model 1) and daily diary (Model 3) data. For the second outcome—with the goal of comparing CAS versus no CAS among sex days—we analyzed the trichotomous variable indicating whether the participant had no sex, sex without CAS, and sex with CAS using a multinomial logistic outcome for TLFB (Model 2) and daily diary (Model 4) data. Though we utilized the multinomial model for statistical reasons in order to calculate estimates using all available data rather than limiting the analytic sample to only sex days, only the comparison between sex with and without CAS was of substantive interest, and thus the comparison with non-sex days is not reported (Models 1 and 3 contain the comparison of sex versus non-sex days). Finally, in order to create and plot marginal probabilities based on the models, we also examined each set of models with an interaction between day-level use and individual-level high frequency of use to allow the impact of day-level use to differ for heavier versus lower frequency users. All models included each of the three substances’ event-level (Level 1) and aggregate individual-level (Level 2) variables entered together to adjust for each other’s effects, were run utilizing a random intercept, and were adjusted for HIV-positive status, relationship status, and day of cycle (i.e., 1 through 42 for TLFB, 1 through 30 for diary) to adjust for any confounding effects.

3. RESULTS

As can be seen in Table 1, the sample was demographically diverse with regard to most characteristics. The sample consisted of approximately half GBM of color, a full range of employment statuses, a wide variety of educational attainments, and was nearly evenly split between HIV-positive and negative men. In contrast, a majority of the sample was gay-identified and single. While marijuana was the substance used most frequently on average in the 42-day TLFB, heavy drinking had the highest median use, suggesting more people engaged in heavy drinking but that marijuana use occurred more frequently among users. Among only those who used each substance, the medians used to split the lower and higher frequency use groups were 6.0 days of heavy drinking, 9.0 days of marijuana use, and 4.0 days of club drug use.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 74 | 19.9 |

| Latino | 50 | 13.5 |

| White | 191 | 51.5 |

| Multiracial/Other | 56 | 15.1 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 327 | 88.1 |

| Bisexual | 44 | 11.9 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 117 | 31.5 |

| Part-time | 94 | 25.3 |

| Student (unemployed) | 31 | 8.4 |

| Unemployed | 127 | 34.2 |

| Not answered | 2 | 0.5 |

| Highest Educational Attainment | ||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 42 | 11.3 |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 113 | 30.5 |

| Bachelor’s or other 4-year degree | 124 | 33.4 |

| Graduate degree | 92 | 24.8 |

| HIV Status | ||

| Positive | 166 | 44.5 |

| Negative | 207 | 55.5 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 297 | 80.1 |

| Partnered | 74 | 19.9 |

| M | SD | |

|

|

||

| Age (Mdn = 35.0) | 37.0 | 11.5 |

| Number of TLFB Heavy Drinking Days (Mdn = 2.0) | 5.4 | 8.5 |

| Number of TLFB Marijuana Use Days (Mdn = 1.0) | 8.1 | 13.6 |

| Number of TLFB Club Drug Use Days (Mdn = 0.0) | 2.4 | 5.8 |

3.1. Aggregate-Only Analyses

Table 2 presents aggregated data regarding the three levels of substance use frequency—no use, lower use, and heavier use—and their association with individual-level dichotomous indicators of CAS from the TLFB and the daily diary as well as the number of CAS acts from the TLFB. Overall, drug use frequency was not significantly associated with any of the aggregated dichotomous indicators of CAS from TLFB or diary. Higher club drug use frequency was significantly associated with a greater number of CAS acts from the TLFB.

3.2. Simultaneous Models of Aggregate and Event-Level Substance Use

Table 3 displays the four multilevel models run. Examining sexual engagement (Models 1 and 3), results revealed significant, positive associations for event-level use of each substance, with use of each substance being associated with at least twice the odds of engaging in sexual behavior on a given day. Across both TLFB and daily diary, club drug use had the strongest effect and the model for the TLFB data (Model 1) showed a stronger association for event-level club drug use than the daily diary model (Model 3).

Table 3.

Multilevel models utilizing day-level and individual-level substance use to predict daily sexual engagement and CAS with casual partners.

| Timeline Follow-Back Combined Models

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| No Sex vs. Sexa

|

No CAS vs. CASb

|

|||||

| b | AOR | 95%CI | b | AOR | 95%CI | |

| Intercept | −0.77 | 0.47*** | 0.38, 0.57 | −1.96 | 0.14*** | 0.10, 0.20 |

| Level 1: Event-Level Effects | ||||||

| Day-level heavy drinking | 0.97 | 2.63*** | 2.28, 3.03 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.87, 1.50 |

| Day-level marijuana use | 1.30 | 3.66*** | 3.06, 4.38 | 0.46 | 1.58** | 1.17, 2.13 |

| Day-level club drugs use | 2.39 | 10.88*** | 8.77, 13.50 | 0.81 | 2.25*** | 1.63, 3.09 |

| Level 2: Dispositional Effects | ||||||

| Frequency of heavy drinking: Lower | −0.35 | 0.70** | 0.55, 0.90 | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.63, 1.57 |

| Frequency of heavy drinking: Higher | −0.37 | 0.69** | 0.54, 0.88 | −0.57 | 0.57* | 0.35, 0.91 |

| Frequency of marijuana use: Lower | −0.18 | 0.84 | 0.65, 1.07 | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.61, 1.52 |

| Frequency of marijuana use: Higher | −0.78 | 0.46*** | 0.35, 0.61 | −0.64 | 0.53* | 0.31, 0.89 |

| Frequency of club drug use: Lower | −0.43 | 0.65** | 0.50, 0.85 | −0.05 | 0.96 | 0.58, 1.59 |

| Frequency of club drug use: Higher | −0.86 | 0.42*** | 0.32, 0.56 | −0.10 | 0.91 | 0.54, 1.53 |

| Daily Diary Combined Models

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| No Sex vs. Sexa

|

No CAS vs. CASb

|

|||||

| b | AOR | 95%CI | b | AOR | 95%CI | |

| Intercept | −0.79 | 0.46*** | 0.36, 0.58 | −1.69 | 0.19*** | 0.13, 0.27 |

| Level 1: Event-Level Effects | ||||||

| Day-level heavy drinking | 0.75 | 2.12*** | 1.77, 2.54 | 0.47 | 1.60** | 1.19, 2.14 |

| Day-level marijuana use | 0.85 | 2.34*** | 1.93, 2.85 | 0.31 | 1.36† | 0.98, 1.89 |

| Day-level club drugs use | 1.60 | 4.94*** | 3.72, 6.56 | 0.94 | 2.56*** | 1.69, 3.86 |

| Level 2: Dispositional Effects | ||||||

| Frequency of heavy drinking: Lower | −0.09 | 0.91 | 0.68, 1.22 | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.71, 1.72 |

| Frequency of heavy drinking: Higher | −0.10 | 0.90 | 0.67, 1.21 | −0.20 | 0.82 | 0.52, 1.28 |

| Frequency of marijuana use: Lower | −0.19 | 0.83 | 0.62, 1.11 | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.72, 1.77 |

| Frequency of marijuana use: Higher | −0.43 | 0.65** | 0.47, 0.90 | −0.63 | 0.53* | 0.32, 0.89 |

| Frequency of club drug use: Lower | −0.43 | 0.65** | 0.47, 0.91 | −0.48 | 0.62† | 0.37, 1.04 |

| Frequency of club drug use: Higher | −0.50 | 0.61** | 0.43, 0.86 | −0.59 | 0.55* | 0.32, 0.95 |

Note:

p ≤ 0.08;

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001.

Binary logistic regression;

Multinomial logistic regression (only one of two comparisons shown). All models were adjusted for HIV-positive status and relationship status as well as day of data collection (i.e., day of TLFB cycle or day of diary cycle). Comparison group for dispositional substance use is the non-use group for each substance.

Focusing on the association between aggregate-level frequency of use and sexual engagement, models for TLFB (Model 1) and daily diary (Model 3) both showed significant, negative associations between higher frequency marijuana use, lower frequency club drug use, and higher frequency club drug use (all compared to non-use), with each being associated with at least a 35% reduction in the odds of engaging in sexual behavior on a given day. The model for the TLFB data (Model 1) again revealed stronger effects than the daily diary model (Model 3) across all effects except that for lower frequency club drug use, which was identical across models. Moreover, within the model for the TLFB data (Model 1), both lower and higher frequency heavy drinking (compared to non-heavy drinkers) were significantly associated with a decreased odds of sexual engagement on a given day.

We next examined the association between event-level substance use and engaging in CAS (versus engaging in sexual activity without CAS) and found that the only consistent finding between the TLFB (Model 2) and daily diary (Model 4) data was the effect of daily club drug use. Specifically, in both models the use of club drugs on a sex day was associated more than twice the odds of engaging in CAS during sex. Additionally, the model of the TLFB data (Model 2) suggested that use of marijuana on a sex day was associated with a 58% increase in the odds of CAS without corroboration in the model for the diary data (Model 4). Conversely, the daily diary data (Model 4) suggested that heavy drinking on a sex day was associated with a 60% increase in the odds of CAS without a similar finding from the TLFB (Model 2).

With regard to the role of individual-level aggregated frequency of substance use on CAS, the only consistently significant effect across both the TLFB (Model 2) and daily diary (Model 4) was that higher frequency marijuana use was associated with a 47% reduction in the odds of CAS on a sex day. Similar to the event-level variables and CAS, each model also had unique effects. Within the TLFB data (Model 2), higher frequency heavy drinking was associated with 43% lower odds of CAS on a sex day and within the daily diary data (Model 4), higher frequency club drug use was associated with 45% lower odds of CAS on a sex day.

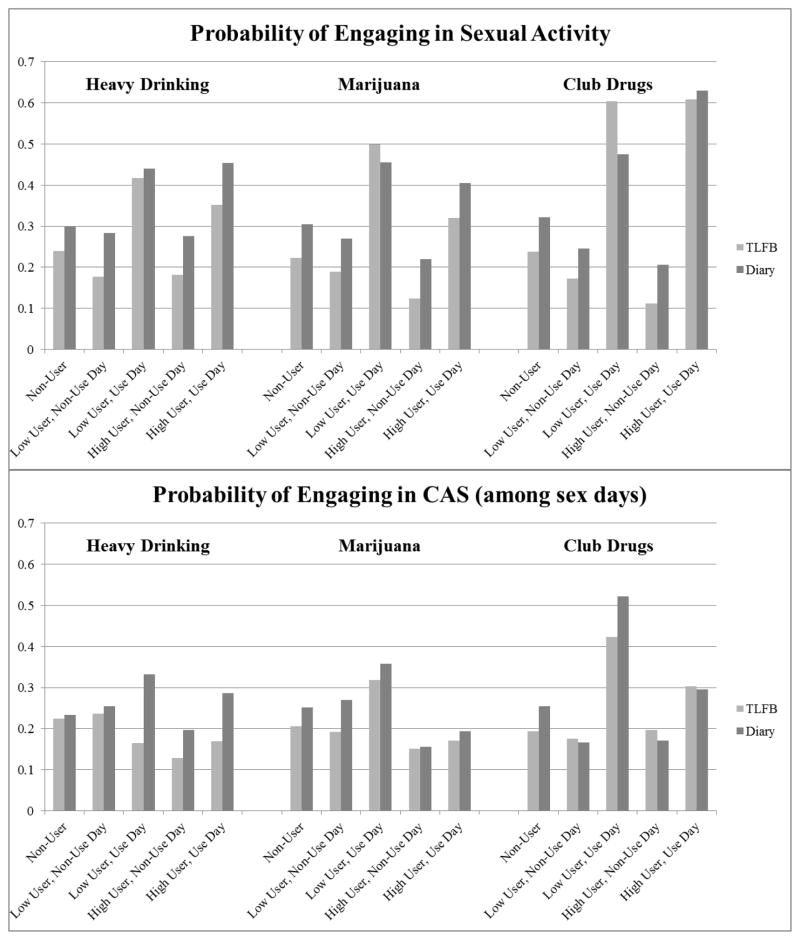

Finally, to provide a clearer sense of how the impact of event-level substance use may differ for different frequency users, Figure 1 graphically represents the marginal predicted probabilities from the same four models above (Models 1 through 4) in which we added an interaction term between event-level use of each substance and aggregated frequency of use. As can be seen, event-level club drug use—the only event-level use variable significantly associated with the outcome in all four models—was associated with a similar probability of engaging in sex on a given day for both the lower and higher frequency club drug users in the TLFB model, but more strongly increased the probability of sex for the higher frequency users in the diary data. Moreover, both the lower and higher frequency club drug using groups had a lower odds of sexual engagement on non-use (i.e., sober) days than did the non-use group across both models. With regards to CAS, both the TLFB and diary models were more consistent—the impact of club drug use on a sex day more strongly increased the odds of CAS for lower frequency users than higher frequency users, and both of these groups had similar odds of CAS on non-use (i.e., sober) days as the non-using group.

Figure 1.

Marginal probabilities of engaging in sexual activity and CAS based on individual-level frequency of use and day-level use of substances from two logistic regressions utilizing TLFB and daily diary data.

4. DISCUSSION

In this manuscript we examined the influence of individual-level aggregated frequency of substance use and event-level use on a given day on daily sexual engagement and CAS simultaneously for three different types of substances—heavy alcohol use, marijuana, and club drugs—using both retrospective (i.e., TLFB) and prospective (i.e., daily diary) data among GBM. When examined alone, the three aggregated frequency of use groups showed no significant differences in aggregate tendencies to engage in CAS or not across the observation period for any of the three drugs, though frequency of club drug user was associated with a higher number of CAS acts in the TLFB. Results of the models in which aggregate individual-level substance use was modeled simultaneously with event-level daily use generally suggested positive associations with sexual behavior for event-level use—particularly club drugs—and negative or null results for aggregated frequency of use, which we discuss in more detail below.

One of the most conceptually meaningful findings was that daily substance use was strongly associated with sexual engagement on that day regardless of which substance was examined and data collection technique (i.e., retrospective or prospective). When simultaneously modeled (i.e., adjusted for one another), heavy drinking and marijuana use showed between a two- and three-fold increase in the odds of sexual engagement on a given day, while club drug use was associated with nearly a five- to ten-fold increase in the odds of having sex on that day. Also consistent across both TLFB and diary data was the more than twofold increase in the odds of CAS on a sex day when club drugs were used and the nearly 50% reduction in the odds of CAS on a sex day for the highest frequency marijuana users.

Overall, these findings are consistent with other data regarding the role of event-level substance use (Chiasson et al., 2007; Colfax et al., 2004; Drumright et al., 2006a; Lambert et al., 2011), including a recent study of HIV-positive GBMSM that found daily alcohol and drug use were both associated with an increased odds of anal intercourse and CAS while adjusting for individual frequency of use (Kahler et al., 2015). However, unlike the research by Kahler et al. and other studies, ours is one of the first to identify a reciprocal association between higher frequency use and both sexual engagement and CAS while accounting for event-level use, which was particularly true for marijuana, though also partially true for club drugs and heavy drinking for sexual engagement as well as at least one of the models of CAS for each. These findings may suggest that heavier frequency users—especially compared with non-users—may be experiencing forms of impairment that actually diminish their ability or interest to engage in sexual behavior in the first place, such as anhedonia (Safren et al., 2010), that may not be seen without adjusting for the strong event-level influence of these substances. In fact, substance users had lower likelihood of both sex and sexual risk on sober days than did non-users. Moreover, most of these variables were unassociated with sexual behavior in the aggregate-only analyses despite their negative association in the multilevel models with the exception of club drug use, which was associated with CAS in the opposite direction in the aggregate-only and multilevel analyses. The stronger event-level associations with sexual engagement than with CAS also suggest that one of the strongest mechanisms through which substance use may act to influence HIV risk behaviors is through increasing the odds of sex in general, coupled with a smaller but still significant increase in the odds of CAS itself. This is somewhat consistent with previous findings from a study by Mustanski (2008), who found alcohol use on a given day was associated with an increased odds of sexual engagement but no association was found between event-level alcohol use and CAS.

Although the findings above were largely consistent across data collection techniques despite previous research (Griffith et al., 2009; Shiffman, 2009), it is also worth noting their inconsistencies. First, TLFB models for sexual engagement showed stronger associations with both aggregate and event-level substance use than the same models with daily diary data. Moreover, more of the aggregate frequency variables were significant with the TLFB data. These findings may highlight a methodological artifact, namely recall bias, whereby people are more likely to remember events that occur together or to remember them as occurring together even if they did not. In fact, one of the primary techniques in the TLFB interview is the use of anchor dates, whereby participants are asked to use important markers on the calendar (e.g., parties, holidays, vacations) to improve their ability to visualize and remember events. Alternatively, this may suggest a bias in the daily diary data whereby participants are less likely to complete diaries on days on which substances were used, thus potentially dampening the association between use and sexual behaviors.

4.1. Limitations

It is important to note that while we believe the general consistency of these findings across substances and data collection techniques highlights their applicability to broader groups, this was a sample of highly sexually active GBM in New York City and thus generalizability is limited. Although we investigated sexual behavior and substance use using two of the most widely used and well-researched methods for retrospective (i.e., TLFB) and prospective (i.e., daily diary) data collection, they nonetheless may have been influenced by the biases inherent to self-report as well as biases inherent to each—namely, recall bias for TLFB and imperfect compliance (i.e., completion rates) for the diary. We investigated a total of four outcomes with numerous predictors per model and may have slightly inflated the chances of Type I error. However, nearly all effects were highly significant (many p-values were less than 0.001), and thus believe the probability of false findings by chance alone is low.

Several contextual influences on sexual behavior, including the influence of partner characteristics such as HIV seroconcordance, were unaccounted for in the present manuscript and may meaningfully interact with substance use to influence sexual behaviors—future studies are needed to investigate the role these contextual influences play in their interaction with substance use. Finally, although we considered it a strength to be able to look at different levels of use compared to non-users in this sample with varying profiles of use, future studies with greater variability of substance use may wish to look at frequency of substance use as a count rather than categorical variable—the use of median splits may have obscured some of the nuance in the association but was chosen due to the lack of clearer guidelines regarding what constitutes higher and lower frequency use. Moreover, the median split had the added benefit of creating equally sized groups of lower and higher frequency users and, with a few exceptions, generally produced results that were somewhat similar in effect across both groups in comparison with the non-use group.

4.2. Conclusions

These findings highlight the role that dispositional and event-level substance use as well as their interaction can play in sexual behavior and suggest that aggregating these effects to the individual level may lead to inappropriate conclusions. Results indicated that findings are largely consistent between retrospective and prospective data, but that retrospective results for substance use and sexual engagement were generally greater in magnitude, suggesting the potential impact of recall bias. These results suggest that substance use largely acts to increase sexual risk at the event-level as opposed to through more dispositional tendencies towards use. Research aiming to investigate the association between substance use and sex may result in contradictory findings that result from methodological imprecision if aggregate data rather than event-level data are used.

Consistent with previous research (Colfax et al., 2004; Rusch et al., 2004), these findings suggest that it is imperative for HIV interventions to target substance use and incorporate effective treatment approaches while considering the types of substances being used and individual use patterns in order to reduce risk. Interventions might aim to target day-level factors that increase both substance use and sexual risk and may as the mechanism through which substance use influences sexual risk (e.g., stress, arousal, impaired cognition) in addition to focusing on dispositional traits (e.g., self-efficacy). Identifying daily cues that trigger substance use, along with other strategies based in cognitive behavioral therapy, such as daily self-monitoring tools, may serve to both enhance self-awareness about the impact of use concurrent with sex and provide tools to clinicians and interventionists to distinguish among the types of substances used and use patterns that have the most impact on sexual risk behavior. Further, our findings indicate that prevention approaches that target only individuals who are addicted to or dependent on alcohol and drugs may miss those who use less frequently despite having similar profiles of sexual behavior to more problematic users. This study helps to develop a more comprehensive picture of substance use and sexual risk than previously offered and calls for improved measurement models in future research to inform prevention approaches aimed at substance use and HIV risk.

Highlights.

We assessed daily substance use and sexual behavior using both retrospective and prospective procedures

We categorized participants’ aggregated tendencies toward use as: non-users, lighter users, or heavier users for heavy drinking, marijuana, and club drugs

We used multilevel modeling to simultaneously investigate aggregate frequency of use as well as event-level daily use on both sexual engagement and condomless anal sex (CAS)

Event-level use generally increased the odds of sexual engagement and CAS, particularly for club drugs

Heavier aggregate use generally decreased the odds of sexual engagement and CAS relative to non-users, particularly for club drugs

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: This project was supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH087714; Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator). Jonathon Rendina was supported in part by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01-DA039030; H. Jonathon Rendina, Principal Investigator). Raymond Moody was supported in part by a research supplement to promote diversity from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466-S2; Jeffrey T. Parsons & Christian Grov, Principal Investigators). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Pillow Talk Research Team: Brian Mustanski, John Pachankis, Ruben Jimenez, Demetria Cain, and Sitaji Gurung. We would also like to thank the CHEST staff who played important roles in the implementation of the project: Chris Hietikko, Chloe Mirzayi, Anita Viswanath, Arjee Restar, and Thomas Whitfield, as well as our team of recruiters and interns. Finally, we thank Chris Ryan, Daniel Nardicio and the participants who volunteered their time for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: Jonathon Rendina was primarily responsible for drafting text, designing and executing analyses, reviewing content, and approving the final manuscript. Raymond Moody was primarily responsible for drafting text, reviewing content, and approving the final manuscript. Ana Ventuneac was primarily responsible for project oversight, data collection, reviewing content, and approving the final manuscript. Christian Grov was the Co-PI on the grant and primarily responsible for project conceptualization, reviewing content, and approving the final manuscript. Jeffrey Parsons was the PI on the grant and primarily responsible for project conceptualization, data collection, reviewing content, and approving the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arasteh K, Des Jarlais DC, Perlis TE. Alcohol and HIV sexual risk behaviors among injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2012. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Wong T, Wolitski RJ. A comparison of on-line and off-line sexual risk in men who have sex with men: an event-based on-line survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:235–243. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802e298c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Coates T, Husnik M, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Chesney M, Vittinghoff E. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82:62–70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Celum C, Chesney M, Huang Y, Mayer K. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant-and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Fromme K. Alcohol use and serial monogamy as risks for sexually transmitted diseases in young adults. Health Psychol. 2002;21:229–236. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, Slymen DJ, Araneta MRG, Malcarne VL, Daar ES, Gorbach PM. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006a;43:344–350. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Club drugs as causal risk factors for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men: a review. Subst Use Misuse. 2006b;41:1551–1601. doi: 10.1080/10826080600847894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GL, White EW, Page-Shafer K, Bein E, Osmond DH, Paul J, Stall RD. Correlates of heavy substance use among young gay and bisexual men: the San Francisco Young Men’s Health Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith SD, Shiffman S, Heitjan DF. A method comparison study of timeline followback and ecological momentary assessment of daily cigarette consumption. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1368–1373. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, Mustanski B, Parsons JT. Sexual compulsivity, state affect, and sexual risk behavior in a daily diary study of gay and bisexual men. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:487–497. doi: 10.1037/a0020527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Millstein SG, Ellen JM. Relationship of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: a review and analysis of findings. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19:331–336. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C, Wray T, Pantalone D, Kruis R, Mastroleo N, Monti P, Mayer K. Daily associations between alcohol use and unprotected anal sex among heavy drinking HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:422–430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman RL, Greenberg JD, Pollack LM, Dolezal C. MDMA (‘ecstasy’) use, and its association with high risk behaviors, mental health, and other factors among gay/bisexual men in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Chesney MA, Husnik MJ, Bozeman S, Celum CL, Buchbinder S, Mayer K, McKirnan D, Judson FN, Huang Y. High-risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in 6 US cities: baseline data from the EXPLORE Study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:926–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert G, Cox J, Hottes TS, Tremblay C, Frigault LR, Alary M, Otis J, Remis RS. Correlates of unprotected anal sex at last sexual episode: analysis from a surveillance study of men who have sex with men in Montreal. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:584–595. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: a meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Steward WT, Charlebois ED, Remien RH, Pinkerton SD, Johnson MO, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lightfoot M, Goldstein RB, Kittel L. Predicting HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: findings from the healthy living project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:226–235. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000166375.16222.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. The influence of state and trait affect on HIV risk behaviors: a daily diary study of MSM. Health Psychol. 2007;26:618–626. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Moderating effects of age on the alcohol and sexual risk taking association: an online daily diary study of men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:118–126. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA newsletter. 2004;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Kowalczyk WJ, Botsko M, Tomassilli J, Golub SA. Aggregate versus day level association between methamphetamine use and HIV medication non-adherence among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013a;17:1478–1487. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0463-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. Predictors of day-level sexual risk for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013b;17:1465–1477. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Cook KF, Grov C, Mustanski B. A psychometric investigation of the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men: an item response theory analysis. J Sex Med. 2013c;10:3088–3101. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JA, Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Solomon TM, Barton SC, Blachman-Forshay J, Siconolfi DE, Love HT. Alcohol use among young men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47:12–21. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.618963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestage GP, Hudson J, Down I, Bradley J, Corrigan N, Hurley M, Grulich AE, McInnes D. Gay men who engage in group sex are at increased risk of HIV infection and onward transmission. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:724–730. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Moss S, Remien RH, Woods WJ, Parsons JT. Illicit substance use, sexual risk, and HIV-positive gay and bisexual men: Differences by serostatus of casual partners. AIDS. 2005;19:S37–S47. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167350.00503.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Mizuno Y, Woods WJ. Substance use and sexual transmission risk behavior of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:185–200. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch M, Lampinen TM, Schilder A, Hogg RS. Unprotected anal intercourse associated with recreational drug use among young men who have sex with men depends on partner type and intercourse role. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:492–498. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135991.21755.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, Mimiaga MJ, Stall R. Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:S74–S77. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbc939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Walstrom P, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among individuals infected with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis 2012 to Early 2013. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:314–323. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0177-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Irving H, Rehm J. Alcohol as a correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS: Review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1021–1036. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Problem Drinkers: Guided Self-Change Treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tawk HM, Simpson JM, Mindel A. Condom use in multi-partnered males: importance of HIV and Hepatitis B status. AIDS Care. 2004;16:890–900. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331290185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, Purcell DW. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1394–1410. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody GE, Donnell D, Seage GR, Metzger D, Marmor M, Koblin BA, Buchbinder S, Gross M, Stone B, Judson FN. Non-injection substance use correlates with risky sex among men having sex with men: Data from HIVNET. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SE, Maisto SA. Alcohol use and risk of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:757–782. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]