AIDS-associated morbidity has diminished due to excellent viral control. Multimorbidity are more prevalent and incident in Swiss HIV-positive persons compared to HIV-negative controls. However, smoking, but not HIV status, had a strong impact on cardiovascular risk and multimorbidity.

Keywords: comorbidity, HIV-infection, multimorbidity

Abstract

Background. Although acquired immune deficiency syndrome-associated morbidity has diminished due to excellent viral control, multimorbidity may be increasing among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons compared with the general population.

Methods. We assessed the prevalence of comorbidities and multimorbidity in participants of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) compared with the population-based CoLaus study and the primary care-based FIRE (Family Medicine ICPC-Research using Electronic Medical Records) records. The incidence of the respective endpoints were assessed among SHCS and CoLaus participants. Poisson regression models were adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking.

Results. Overall, 74 291 participants contributed data to prevalence analyses (3230 HIV-infected; 71 061 controls). In CoLaus, FIRE, and SHCS, multimorbidity was present among 26%, 13%, and 27% of participants. Compared with nonsmoking individuals from CoLaus, the incidence of cardiovascular disease was elevated among smoking individuals but independent of HIV status (HIV-negative smoking: incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2–2.5; HIV-positive smoking: IRR = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.1–2.6; HIV-positive nonsmoking: IRR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.44–1.4). Compared with nonsmoking HIV-negative persons, multivariable Poisson regression identified associations of HIV infection with hypertension (nonsmoking: IRR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.5–2.4; smoking: IRR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.6–2.4), kidney (nonsmoking: IRR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.9–3.8; smoking: IRR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.9–3.6), and liver disease (nonsmoking: IRR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.4–2.4; smoking: IRR = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.4–2.2). No evidence was found for an association of HIV-infection or smoking with diabetes mellitus.

Conclusions. Multimorbidity is more prevalent and incident in HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative individuals. Smoking, but not HIV status, has a strong impact on cardiovascular risk and multimorbidity.

Combination antiretroviral treatment has significantly improved life expectancy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals [1]. With close to normal life expectancy, HIV-positive persons may face sequential or concurrent comorbidities leading to increased mortality and multimorbidity [2, 3]. Multimorbidity, often defined as co-occurrence of more than 2 conditions [4], is known to negatively affect health outcomes including a decline in functional status, increased disability, and lower quality of life. Another consequence of multimorbidity is an increased number of medications (polypharmacy) [5].

An important focus of current clinical HIV research is to identify whether HIV-positive individuals with suppressed viral replication develop earlier or different comorbidities compared with HIV-negative persons. Previous comparisons have shown conflicting results regarding cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, psychiatric disorders, and diseases of bone, lung, kidney, and liver [6–21]. Possible reasons for the discrepancies are differences in the selection of the HIV-negative controls, either nested within a population with comparable life styles [7–10, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 22] or based on administrative data from the same geographic area or hospital [11, 14, 16, 19–21]. Other reasons include the limitations of adjusting for important confounders such as smoking or body mass index (BMI) [8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 20].

The aim of the present study is to compare the prevalence and incidence of different comorbidities and multimorbidity in participants of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) with 2 HIV-negative populations in Switzerland.

METHODS

Data Sources Included in the Study

The SHCS [23] was established in 1988 and is an open cohort study with continued enrollment of cumulatively approximately 18 000 HIV-infected persons, aged ≥16 years. Demographic, psychosocial, clinical, laboratory, and treatment information is systematically collected every 6 months. Information on cardiovascular endpoints, diabetes mellitus, and renal and liver disease is ascertained and centrally adjudicated within the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study [24].

Cohorte Lausannoise (CoLaus) [25] is a population-based study that investigates the clinical, biological, and genetic determinants of CVD. Cohorte Lausannoise performs endpoint adjudication of cardiovascular events, diabetes, and psychiatric disorders. Moreover, they have access to the electronic patient records of the hospitals and are linked to the death registry. Participants aged 35–75 years old were recruited in 2003 among 19 830 randomly selected inhabitants of Lausanne, Switzerland. The baseline characterization of 6182 participants was performed during 2003–2006, and a first follow-up visit on more than 5000 of these individuals was done during 2009–2013.

Family Medicine ICPC-Research using Electronic Medical Records (FIRE) [26] is a Swiss primary care project that has enrolled approximately 150 000 patients from 75 general practitioners since 2009 and uses medical data retrieved from electronic patient records. Laboratory results and demographical and clinical information are collected at routine visits. Morbidity is classified according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2) codes [27], and information on the type of prescribed medications is based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification System (ATC) [28]. The FIRE analyzed prevalence estimates of chronic conditions in a recent study and found an age- and gender-specific distribution comparable with other primary care data sources in Switzerland [29]. Information on smoking and alcohol use has not yet been collected in FIRE, and there is only limited information on liver disease and weight available. There is an inherent selection bias in BMI measurements in FIRE because the weight was more likely assessed in case of overweight or obese participants. The FIRE data could not be used for incidence analysis due to limited accumulated follow-up time.

Study Participants

Individuals from SHCS and CoLaus were eligible if they were Caucasian, noninjecting drug users (non-IDUs), ≥35 years old at a study visit 2003–2006 (baseline), and if they had at least 1 follow-up visit 5–6 years later. The FIRE patients were eligible if they were Caucasian, non-IDUs, ≥40 years old, and if they had ≥1 visit between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2011. Thus, all participants were at least 40 years old in 2009–2011 and contributed to prevalence analyses. For the conceptual design, refer to Supplementary Figure 1. All cohorts were approved by the local Ethics Committees.

Definitions

Clinical events were validated according to the standards of each cohort. We collected information on the following clinical events: CVDs (myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease with/without angina, heart failure and coronary heart disease, coronary artery bypass graft, and coronary angioplasty/stenting); stroke; diabetes mellitus (diabetes mellitus insulin-dependent/insulin-resistant and use of oral antidiabetics or insulin [ATCA10*, Pharmaceutical Cost Group (PCG): A10]); hypertension (measured diastolic or a systolic blood pressure >90/>160 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medications [ATC C0*; PCG: C02, C03A, C03EA01 C07, C08, C09A, C09B]); kidney insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula) [30]; and liver event (alanine transaminase [ALT] >50 U/L for males/35 U/L for females). We used the term “comorbidities” throughout the manuscript. Multimorbidity was termed as the co-occurrence of at least 2 of the above-mentioned conditions (ie, ≥2 comorbidities). By definition, HIV infection was not considered as a comorbid condition. In CoLaus and SHCS, comedications were recorded according to the ATC [28], and FIRE was applied to a PCG model [27]. We recorded the use of antihypertensives and antidiabetics. A table indicating the definitions of each clinical event is available in the appendix (Supplementary Table 1).

Patients were stratified by the following BMI categories: underweight, <18.5 kg/m2; normal, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2; overweight, 25–29.9 kg/m2); and obese, ≥30 kg/m2 [31]. We distinguished 2 smoking categories: ever/current smokers and nonsmokers. Age was stratified into <50, 50–65, and 65+ years. Information on HIV infection included years since first HIV diagnosis and cumulative exposure to drug classes (protease inhibitor [PI], nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NNRTI]-based antiretroviral therapy [ART] combinations).

Statistical Analysis

Differences between cohorts were analyzed by χ2 tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. We calculated the cumulative prevalence of endpoints for CoLaus, FIRE, and SHCS until end of 2011. Logistic regression analyses were adjusted for age groups and sex among all cohorts, and in SHCS and CoLaus models were further adjusted for smoking and BMI.

We calculated incidence rates of endpoints as the number of new endpoints since the first visit in 2003–2006 divided by the number of person-years of follow up. The time at risk for patients without an event was calculated as time between the baseline visit and the follow-up visit. In case of an event, we used the time from baseline until the date of the event. Because precise dates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, kidney disease, and liver disease were not available in CoLaus, we used the midpoint between the baseline and follow-up visit for these events. To check whether this approximation was valid, we compared CoLaus estimates for cardiovascular events and stroke using the available dates with the estimates using the midpoint of baseline and follow-up visit. The findings were unchanged (data not shown). Comparisons of incidence across CoLaus and SHCS were done with Poisson regression adjusted for sex, age groups, BMI groups, and smoking as an interaction term. To rule out important effect attenuation by using stratified age and BMI values, we performed sensitivity analyses using continuous age and BMI measurements. We excluded IDUs and therefore we assumed hepatitis C virus (HCV) would not contribute to the endpoint liver disease. To check this, we performed a sensitivity analysis and excluded HCV-infected individuals in other HIV transmission groups than IDUs. We used Stata/SE (version 13.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analyses.

RESULTS

Patients Characteristics

Characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Compared with the SHCS, participants from FIRE and CoLaus were older, more frequently female, and had a higher BMI; previous or current smoking was more prevalent in the SHCS than in CoLaus.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 74 291 Participants, Stratified by Cohort

| Variables | Cohorts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoLaus 2009–2011 | FIREa 2009–2011 | SHCS 2009–2011 | P Valueb | |

| Participants, n (%) | 4569 (6) | 66 492 (90) | 3230 (4) | – |

| Female, n (%) | 2450 (54) | 34 968 (53) | 607 (19) | <.001 |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 57 (49–67) | 59 (49–72) | 50 (45–58) | <.001 |

| Smoking, ever, n (%) | 2725 (60) | – | 2166 (68) | <.001 |

| Smoking, current, n (%) | 989 (22) | – | 1179 (37) | <.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 26 (23–29) | 27 (24–30) | 24 (22–26) | <.001 |

| BMI groups, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| underweight | 71 (2) | 168 (0) | 153 (5) | |

| normal | 1929 (42) | 3853 (6) | 1879 (58) | |

| overweight | 1778 (39) | 4945 (7) | 969 (30) | |

| obese | 791 (17) | 3384 (5) | 2249 (7) | |

| missing | 0 (0) | 54 142 (81) | 0 (0) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; SHCS, Swiss HIV Cohort Study; CoLaus, Cohorte Lausannoise; FIRE, Family Medicine ICPC-Research using Electronic Medical Records.

a Information on smoking is missing and BMI is available only for 12 350 FIRE participants.

b P values from 2 × 3 χ2 tests (categorical variables) and Kruskal-Wallis tests (continuous variables).

The median duration of HIV infection in the SHCS was 14 years (interquartile range [IQR], 9.5–19). Median exposure times to PI or NNRTI-based ART regimens were 4.5 years (IQR, 0.99–8.8) and 2.6 years (IQR, 0.0–6.6), respectively. Nadir CD4 cell count was 172 (70–259), latest CD4 count was 572 (IQR, 420–754) cells/µL, and 880 (27%) of SHCS participants had a prior acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining event. The percentage of SHCS participants on ART with an event was between 96.4% and 100%, depending on the respective endpoint. Median CD4 cells among those with or without (1) CVD and (2) stroke, liver or kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension were as follows, respectively: CVD, 459.5 (IQR, 340–602) and 508 (IQR, 370–699) cells/L; stroke, 443 (IQR, 270–590) and 522.5 (IQR, 386–798) cells/L; liver disease, 570 (IQR, 430–763) and 571 (IQR, 424.5–751) cells/L; kidney disease, 511 (IQR, 397–695) and 572 (IQR, 430–758) cells/L; diabetes, 560 (IQR, 384–850) and 510 (IQR, 373–701) cells/L; and hypertension, 544 (IQR, 392–731) and 549 (IQR, 404–735) cells/L.

Prevalence Analyses

A total of 4569 CoLaus participants, 66 492 FIRE participants, and 3230 SHCS participants contributed to the prevalence analyses of different comorbidities. Multimorbidity was present in 26%, 13%, and 27% for CoLaus, FIRE, and SHCS, respectively.

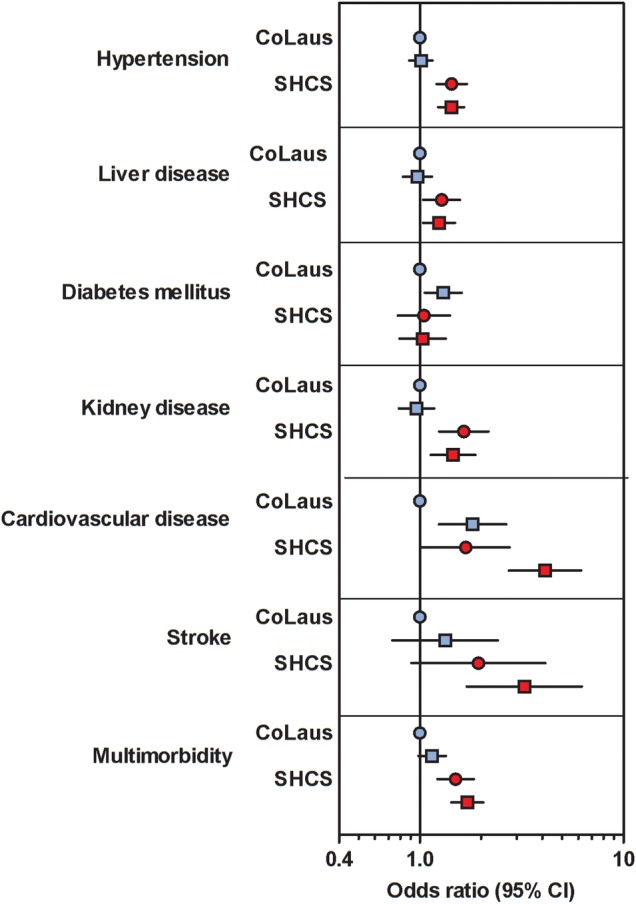

In unadjusted logistic regression analysis, most comorbidities were less prevalent in FIRE participants compared with CoLaus and SHCS. When comparing the SHCS with CoLaus, the unadjusted prevalence of CVD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.2–1.9) and liver disease (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 1.1–1.4) were increased, and diabetes mellitus (OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.51–0.71) and kidney disease (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.65–0.88) were less prevalent among HIV-infected individuals. Adjusted models, only SHCS and CoLaus showed associations of HIV with all comorbidities (CVD: OR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.6–2.7; stroke: OR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.4–3.6; hypertension: OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.62–0.77; kidney disease: OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.5–2.2; liver disease: OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.5–2.0) except for diabetes mellitus resulting in an adjusted OR of 1.7 (95% CI = 1.5–2.0) for multimorbidity. Table 2 shows unadjusted and adjusted results of logistic regression with smoking as an interaction term. We found evidence of an increased prevalence of CVD among smoking individuals irrespective of HIV status. Hypertension, kidney disease, and liver disease were associated with HIV-infection but not with smoking. For stroke, HIV and smoking had an additive effect. Diabetes mellitus was associated with HIV-negative, smoking individuals (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Numbers of Prevalent Comorbidities, Stratified by Cohorta

| Cohort | All Events, n (%) | Hypertension, n (%) | Liver Disease, n (%) | Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | Kidney Disease, n (%) | Cardiovasc. Disease, n (%) | Stroke, n (%) | Multimorbidity, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoLaus nonsmoking | 1844 (100) | 842 (46) | 298 (16) | 167 (9) | 207 (11) | 38 (2) | 17 (1) | 373 (20) |

| CoLaus smoking | 2725 (100) | 1296 (48) | 451 (17) | 358 (13) | 273 (10) | 114 (4) | 34 (1) | 647 (24) |

| FIRE | 66 492 (100) | 22 206 (33) | −b | 4500 (7) | 509 (1) | 2407 (4) | 699 (1) | 5661 (9)b |

| SHCS nonsmoking | 1064 (100) | 515 (48) | 212 (20) | 89 (8) | 102 (10) | 33 (3) | 14 (1) | 233 (22) |

| SHCS smoking | 2166 (100) | 941 (43) | 405 (19) | 146 (7) | 161 (7) | 126 (6) | 37 (2) | 448 (21) |

| Unadjusted logistic regression | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| CoLaus nonsmoking | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CoLaus smoking | 1.1 (0.96–1.2) | 1.0 (0.88–1.2) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.88 (0.73–1.1) | 2.1 (1.4–3.0) | 1.4 (0.76–2.4) | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | |

| FIRE | 0.60 (0.54–0.65) | – | 0.73 (0.62–0.86) | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | 1.1 (0.70–1.9) | 0.59 (0.51–0.67)b | |

| SHCS nonsmoking | 1.1 (0.96–1.3) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.92 (0.70–1.2) | 0.84 (0.65–1.1) | 1.5 (0.95–2.4) | 1.4 (0.70–2.9) | 1.1 (0.92–1.3) | |

| SHCS smoking | 0.91 (0.81–1.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.73 (0.58–0.91) | 0.64 (0.51–0.79) | 2.9 (2.0–4.2) | 1.9 (1.0–3.3) | 1.0 (0.88–1.2) | |

| Adjusted logistic regressionc | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| CoLaus nonsmoking | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CoLaus smoking | 1.0 (0.89–1.1) | 0.97 (0.82–1.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.96 (0.79–1.2) | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) | 1.3 (0.73–2.4) | 1.1 (0.98–1.3) | |

| FIREc | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| SHCS nonsmoking | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.0 (0.78–1.4) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 1.9 (0.91–4.1) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | |

| SHCS smoking | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.0 (0.79–1.3) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 4.1 (2.7–6.2) | 3.2 (1.7–6.2) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | |

| Female sex | 0.69 (0.62–0.77) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | 0.42 (0.35–0.51) | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 0.45 (0.33–0.60) | 0.75 (0.47–1.2) | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) | |

| Age group, 50–65 yd | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 1.0 (0.90–1.2) | 2.6 (2.0–3.2) | 2.9 (2.2–3.7) | 4.6 (3.0–7.0) | 3.5 (1.6–7.3) | 3.4 (2.7–4.2) | |

| Age group, +65yd | 5.2 (4.5–5.9) | 0.61 (0.51–0.73) | 5.5 (4.3–7.0) | 9.0 (7.0–12) | 15 (1.2–1.9) | 16 (7.9–34) | 12 (10–16) | |

| Normal weighte | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.83 (0.56–1.2) | 1.2 (0.57–2.7) | 0.60 (0.39–0.91) | 0.94 (0.46–1.9) | 1.7 (0.40–7.1) | 0.84 (0.53–1.3) | |

| Overweighte | 2.7 (2.0–3.7) | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 2.9 (1.3–6.2) | 0.78 (0.51–1.2) | 1.1 (0.53–2.2) | 1.5 (0.34–6.3) | 1.5 (0.94–2.4) | |

| Obesee | 6.2 (4.4–8.6) | 2.9 (1.9–4.3) | 8.3 (3.8–18) | 0.85 (0.54–1.3) | 1.6 (0.74–3.3) | 1.8 (0.39–8.0) | 3.8 (2.4–6.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; Cardiovasc., cardiovascular; CI, confidence interval; CoLaus, Cohorte Lausannoise; FIRE, Family Medicine ICPC-Research using Electronic Medical Records; OR, odds ratio; SHCS, Swiss HIV Cohort Study; y, year old.

a Unadjusted and adjusted results of logistic regression analyses with smoking as an interaction term. Adjusted logistic regression models were adjusted for all variables listed.

b There is only limited information on liver endpoints available in FIRE. Therefore, we do not provide the liver endpoint for FIRE, and the multimorbidity endpoint for FIRE includes no liver disease.

c Reference group: nonsmoking participants from CoLaus. FIRE was omitted in multivariable models due to missing information on smoking and limited avilability of BMI values.

d Reference group: 35- to 49-year-old participants.

e Reference group: underweight participants.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of comorbidities derived from logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking as an interaction term among 3230 Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) and 4569 Cohorte Lausannoise (CoLaus) participants. Nonsmoking participants of CoLaus formed the reference group. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Incidence Analyses

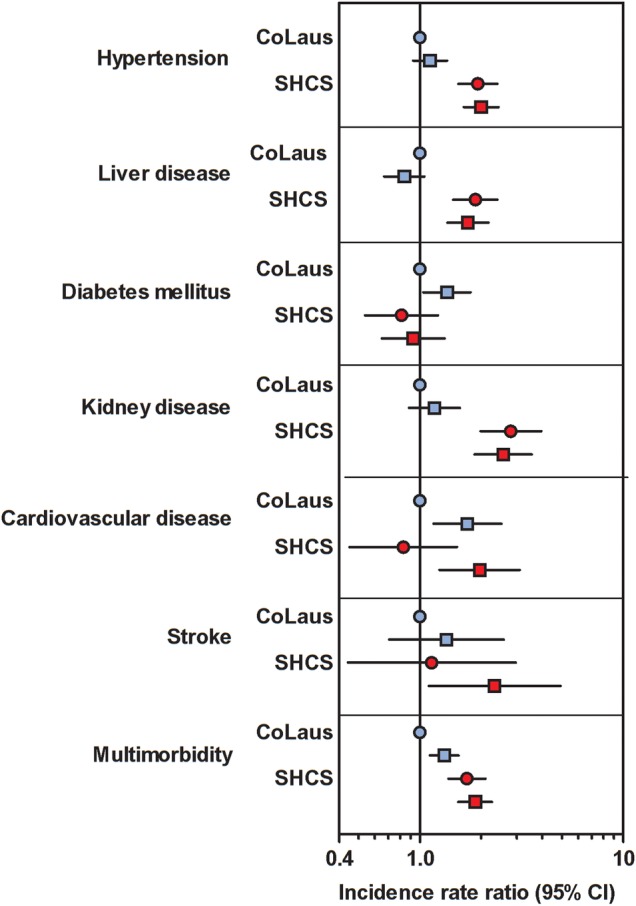

The 3230 SHCS and 4569 CoLaus participants contributed 43 313 person-years of follow up and an average follow up of 5.5 years per person. Compared with CoLaus, we observed higher adjusted incidences of hypertension (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.6–2.1), kidney disease (IRR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.6–2.1), and liver disease (IRR = 1.8, 95% = CI 1.6–2.1) and a lower rate of diabetes mellitus (IRR = 0.72, 95% = CI 0.56–0.93) among SHCS participants. Table 3 and Supplementary Table 3 show the incidence rates and unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios of different comorbidities with smoking as an interaction term. Adjusted analyses showed a different effect of smoking status for the respective comorbidities. As shown in Figure 2, incident CVD and—to a lesser extent—stroke were not increased among HIV-positive patients when stratified by smoking. Hypertension and kidney and liver disease appeared more frequently among HIV-positive individuals irrespective of smoking. Incidences of all comorbidities except liver disease increased with age in each cohort. Results from sensitivity analyses using continuous age and BMI values instead of stratified variables were similar. The association of HIV with the liver disease remained unchanged after excluding HCV-infected individuals in the SHCS.

Table 3.

Numbers of Incident Comorbidities, Stratified by Cohorta

| Comorbidities Among Cohort Participants | Hypertension IR (95% CI) | Liver Disease IR (95% CI) | Diabetes Mellitus IR (95% CI) | Kidney Disease IR (95% CI) | Cardiovasc. Disease IR (95% CI) | Stroke IR (95% CI) | Multimorbidity IR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoLaus nonsmoking | 26 (22–30) | 15 (13–18) | 8.5 (6.8–11) | 8.2 (6.6–10) | 3.5 (2.6–4.9) | 1.4 (0.81–2.3) | 23 (20–26) |

| CoLaus smoking | 31 (28–35) | 13 (11–15) | 13 (11–15) | 9.0 (7.5–11) | 7.0 (5.7–8.4) | 1.9 (1.4–2.8) | 32 (29–35) |

| SHCS nonsmoking | 49 (42–56) | 29 (25–34) | 6.0 (4.3–8.3) | 13 (10–16) | 2.6 (1.6–4.3) | 1.1 (0.54–2.4) | 30 (26–35) |

| SHCS smoking | 47 (41–52) | 26 (23–30) | 5.6 (4.3–7.1) | 11 (8.8–13) | 5.2 (4.0–6.7) | 2.0 (1.3–3.0) | 38 (25–31) |

| Unadjusted poisson regression | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) |

| CoLaus nonsmoking | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CoLaus smoking | 1.2 (0.98–1.4) | 0.84 (0.67–1.1) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.1 (0.82–1.4) | 2.0 (1.1–2.9) | 1.4 (0.75–2.7) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) |

| SHCS nonsmoking | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | 0.71 (0.47–1.0) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.74 (0.41–1.3) | 0.82 (0.33–2.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

| SHCS smoking | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 0.66 (0.47–0.91) | 1.3 (0.96–1.7) | 1.5 (0.96–2.2) | 1.4 (0.74–2.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| Adjusted poisson regressionb | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) |

| CoLaus nonsmokingc | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CoLaus smoking | 1.1 (0.92–1.4) | 0.84 (0.67–1.1) | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 1.2 (0.89–1.6) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 1.3 (0.71–2.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

| SHCS nonsmoking | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | 0.81 (0.54–1.2) | 2.8 (2.0–4.0) | 0.83 (0.45–1.5) | 1.1 (0.44–3.0) | 1.7 (1.1–2.1) |

| SHCS smoking | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | 1.7 (1.4–2.2) | 0.93 (0.65–1.3) | 2.6 (1.9–3.5) | 2.0 (1.2–3.1) | 2.3 (1.1–4.9) | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) |

| Female sex | 0.65 (0.56–0.76) | 1.1 (0.91–1.3) | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 0.44 (0.31–0.61) | 0.72 (0.42–1.2) | 0.70 (0.55–0.88) |

| Age group, 50–65yd | 1.7 (1.5–1.9) | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) | 4.61 (2.8–5.9) | 5.0 (2.5–9.7) | 1.8 (1.43–2.2) |

| Age group, +65ye | 2.4 (2.0–3.0) | 0.32 (0.22–0.47) | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | 6.7 (5.0–8.9) | 10 (6.9–16) | 14 (6.6–28) | 2.6 (1.9–3.5) |

| Normal weighte | 1.1 (0.75–1.7) | 1.1 (0.68–1.9) | 3.4 (0.47–25) | 0.68 (0.39–1.2) | 1.4 (0.44–4.4) | 0.56 (0.17–1.8) | 1.6 (0.69–3.5) |

| Overweighte | 1.8 (1.1–2.7) | 1.6 (0.93–2.6) | 10 (1.4–74) | 0.82 (0.47–1.4) | 1.4 (0.43–4.4) | 0.58 (0.17–2.0) | 2.2 (0.97–5.0) |

| Obesee | 2.5 (1.6–4.0) | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | 25 (3.4–178) | 1.0 (0.55–1.8) | 2.2 (0.68–7.3) | 0.73 (0.20–2.7) | 3.4 (1.5–7.9) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CoLaus, Cohorte Lausannoise; IR, incidence rate per 1000 person years of follow-up; IRR, incidence rate ratio; SHCS, Swiss HIV Cohort Study; y, year old.

a Unadjusted and adjusted results of poisson regression analyses with smoking as an interaction term.

b Poisson regression models were adjusted for all variables listed.

c Reference group: nonsmoking participants from CoLaus.

d Reference group: 35- to 49-year-old participants.

e Reference group: underweight participants.

Figure 2.

Incidence rate ratios of comorbidities derived from poisson regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking as an interaction term among 3230 Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) and 4569 Cohorte Lausannoise (CoLaus) participants. Nonsmoking participants of CoLaus formed the reference group. CI, confidence interval. Nonsmoking participants of CoLaus formed the reference group. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Incident multimorbidity was found in 1147 of 7799 (15%) subjects. Compared with nonsmoking CoLaus participants, incident multimorbidity was increased among nonsmoking and smoking SHCS participants with IRR of 1.7 (95% CI = 1.4–2.1) and 1.9 (95% CI = 1.5–237), respectively. Eighty percent of multimorbid SHCS participants had 2 comorbidities, 19% had 3 comorbidities, and 1.3% had 4 or more comorbidities. Among SHCS participants, the most frequent combinations were as follows: hypertension plus liver disease (29%), hypertension plus diabetes (23%), or hypertension plus kidney disease (14%). The most frequent combinations among CoLaus participants were as follows: hypertension plus diabetes mellius (41%), hypertension plus liver disease (14%), and hypertension plus kidney disease (12%).

DISCUSSION

In this comparative analysis of an HIV cohort (SHCS) with a population-based (CoLaus) and a primary care-based study (FIRE) in Switzerland, we found evidence for an increased prevalence and incidence of comorbidity and multimorbidity among Swiss HIV-positive persons. The prevalence and incidence of CVD was similar among HIV-positive and -negative patients when stratified by smoking status. There was an excess prevalence and incidence among HIV-positive individuals for hypertension, kidney, and liver disease that was independent of smoking. For incident stroke, HIV and smoking appeared to have an additive effect. We did not find evidence for an increased prevalence or incidence of diabetes mellitus associated with HIV infection or smoking.

The effect of HIV on CVD and stroke disappears after adjustment for BMI and smoking. The comparison of our findings with published literature is difficult because either combined cardiovascular endpoints, acute myocardial infarction only, or separated individual components of CVD were reported. Most importantly, adjustment for smoking and BMI is lacking in many studies [8, 9, 14, 16, 20]. However, our results are in line with recent studies. Rasmussen et al [21] investigated HIV-infected individuals with incident mycocardial infarction from the Danish HIV Cohort Study and compared them with population controls matched on age and gender. They found higher rates of mycocardial infarction in smoking individuals irrespective of HIV status (HIV+ nonsmoking: IRR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.41–2.54; HIV+ previous and current smokers: IRR = 1.78, 95% CI = 0.75–4.24); and adjusted IRR = 2.83, 95% CI, = 1.71–4.70). The Veterans aging Cohort primarily investigated the age at, and the risk of incident diagnosis of, myocardial infarction, kidney disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancer. Althoff et al [22] did not find a difference in the age at diagnosis of these age-associated diseases compared with HIV-negative individuals, again challenging the concept of premature aging among HIV patients. Our results of increased risks of kidney and liver disease but not of diabetes mellitus among HIV-positive individuals are congruent with published studies [9, 12, 15–18, 20]. Findings regarding an association of hypertension with HIV have been inconsistent: although the AGEhIV study in the Netherlands [17] and our study found strong associations of HIV with hypertension, other studies reported no [15, 20] or even negative associations of HIV [9] with hypertension.

Finding adequate HIV-negative control groups to identify the independent effect of HIV on age-related comorbidities is challenging. The approaches differ from study to study and may contribute to the heterogeneity of observed results. Some studies have included HIV-negative persons from the same healthcare plan [9, 12, 13], same clinics [8, 17], focused on specific risk groups [15], used individual administrative data from the region [11, 16, 18, 20, 21], or used published data from the general population [14]. In our study, CoLaus, a well documented prospective HIV-negative cohort with validated endpoints, contributed to prevalence and incidence analyses, and FIRE, a large patient registry from private physicians, contributed to prevalence analyses. Because participants in CoLaus likely are a selection of motivated health-seeking persons, the absence of an increased cardiovascular risk in our study, when comparing SHCS and CoLaus participants, is noteworthy. The FIRE participants, on the other hand, are observed by general practicioners, and thus they may be expected to be healthier, which may explain the lower prevalence of multimorbidity in FIRE.

Several limitations should be noted. We were unable to include some important conditions such as cancer, osteoporosis, and pulmonary disease. There might be important lifestyle and socioeconomic demographics differences among comparator groups. Hence, we excluded IDUs because of significant imbalances between the cohorts and the resulting confounding. Underreporting of a history of IDU in SHCS participants with other known risk factors for HIV is possible. Alanine transaminase elevations may be transient in nature, and hence it might not be appropriate to take ALT elevations as a proxy for “liver disease”. However, recent literature indicates that high ALT levels are associated with a higher risk of liver-related mortality and diabetes [32]. As a condition for incidence analyses, we required that participants must have survived at least 6 years. There is no formal record linkage with other hospitals, and hence we cannot exclude that information on comorbidities is not complete. Three hundred of 3998 (7.5%) SHCS participants and 184 of 6122 (3%) CoLaus participants died in 2003–2011. Among the 300 SHCS participants who died, 20 (6%) died from a cardiovascular event. Swiss HIV Cohort Study participants had a median of 9 follow-up visits, whereas CoLaus participants had only 1 follow-up visit. Therefore, we cannot exclude a differential recall bias. Finally, the multivariable analyses were adjusted for a small number of shared variables only, and therefore residual confounding cannot be excluded.

CONCLUSIONS

In our study, we have identified associations of HIV with increased risks of hypertension and kidney and liver disease, unlike CVD where the risk is associated with smoking. It remains to be shown whether these associations with HIV are due to direct viral or immunological mechanisms, coinfections (eg, viral hepatitis, cytomegalovirus), or antiretroviral treatment [33]. In this respect, cohort studies play an important role in pointing basic research to relevant areas and provide phenotypes and biological samples. However, it is obvious that multimorbidity is a very heterogeneous composite endpoint with varying causes that require different approaches for prevention. In conclusion, from a clinical perspective, our results suggest that emphasis should be given to smoking cessation and lifestyle interventions. Furthermore, blood pressure and kidney as well as liver function should be carefully monitored among HIV patients, keeping in mind the increasing risk of drug-drug interactions with increasing polypharmacy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary material is available online at Open Forum Infectious Diseases (http://OpenForumInfectiousDiseases.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Nevill for assistance in data management and data merger. We also thank all involved physicians, study nurses, and most importantly, participants of the respective cohorts.

Authors contributions. B. H. had full access to all of the data of the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. B. H. and B. L. designed the study; B. H. wrote the first draft; and B. H., P. E. T., and B. L. wrote the final version of the manuscript. B. L., P. M.-V., and F. V. analyzed the data. All investigators contributed to data collection and interpretation of the data, reviewed drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support. This study was financed within the framework of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS Study number 716), supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 134277). The data are gathered by the 5 Swiss University Hospitals, 2 Cantonal Hospitals, 15 affiliated hospitals, and 36 private physicians. The funding source had no influence on design or conduct of the study.

The CoLaus study was and is supported by research grants from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of Lausanne, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants 3200B0-105993, 3200B0-118308, 33CSCO-122661, and 33CS30-139468).

Potential conflicts of interest. B. H. has received travel grants from Gilead Sciences. P. E. T.'s institution has received advisory fees from MSD and honoraria from ViiV Healthcare. G. W. received an unrestricted grant from GSK to build the CoLaus study. R. A.'s institution has received travel grants, grants, or honoraria from Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GSK, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, and Tibotec. P. Ve.'s institution has received, travel grants for conference attendance, advisory fees, and honoraria from MSD, Gilead, Pfzier, GSK, Abbvie, Janssen, BMS, and ViiV. R. W. has received travel grants from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Merck Sharp & Dome, Pfizer, Roche, TRB Chemedica. and Tibotec. R. W.'s institution has received unrestricted educational grants from GSK, ViiV, and Gilead Sciences. P. Vo. received an unrestricted grant from GSK to build the CoLaus study. B. L. has received travel grants and grants or honoraria from Abbott, Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GSK, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, and Tibotec.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: the CoLaus Cohort, FIRE and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, V Aubert, J Barth, M Battegay, E Bernasconi, J Böni, HC Bucher, C Burton-Jeangros, A Calmy, M Cavassini, M Egger, L Elzi, J Fehr, J Fellay, H Furrer, CA Fux, M Gorgievski, H Günthard, D Haerry, B Hasse, HH Hirsch, I Hösli, C Kahlert, L Kaiser, O Keiser, T Klimkait, R Kouyos, H Kovari, B Ledergerber, G Martinetti, B Martinez de Tejada, K Metzner, N Müller, D Nadal, G Pantaleo, A Rauch, S Regenass, M Rickenbach, C Rudin, F Schöni-Affolter, P Schmid, D Schultze, J Schüpbach, R Speck, C Staehelin, P Tarr, A Telenti, A Trkola, P Vernazza, R Weber, S. Yerly, Aubry Jean-Michel, Bochud Murielle, Gaspoz Jean Michel, Hock Christoph, Lüscher Thomas, Marques Vidal Pedro, Mooser Vincent, Paccaud Fred, Preisig Martin, Vollenweider Peter, Von Känel Roland, Vladeta Aidacic, Waeber Gerard, Beriger Jürg, Bertschi Markus, Bhend Heinz, Büchi Martin, Bürke Hans-Ulrich, Bugmann Ivo, Cadisch Reto, Charles Isabelle, Chmiel Corinne, Djalali Sima, Duner Peter, Erni Simone, Forster Andrea, Frei Markus, Frey Claudius, Frey Jakob, Gibreil Musa Ali, Günthard Matthias, Haller Denis, Hanselmann Marcel, Häuptli Walter, Heininger Simon, Huber Felix, Hufschmid Paul, Kaiser Eva, Kaplan Vladimir, Klaus Daniel, Koch Stephan, Köstner Beat, Kuster Benedict, Kuster Heidi, Ladan Vesna, Lauffer Giovanni, Leibundgut Hans Werner, Luchsinger Phillippe, Lüscher Severin, Maier Christoph, Martin Jürgen, Meli Damian, Messerli Werner, Morger Titus, Navarro Valentina, Rizzi Jakob, Rosemann Thomas, Sajdl Hana, Schindelek Frank, Schlatter Georg, Senn Oliver, Somaini Pietro, Staeger Jacques, Staehelin Alfred, Steinegger Alois, Steurer Claudia, Suter Othmar, Truong The Phuoc, Vecellio Marco, Violi Alessandro, Von Allmen René, Waeckerlin Hans, Weber Fritz, Weber-Schär Johanna, Widler Joseph, and Zoller Marco

References

- 1.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008; 372:293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deeks SG, Phillips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ 2009; 338:a3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51:367–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007; 5:345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS 2006; 20:2165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crothers K, Butt AA, Gibert CL et al. Increased COPD among HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative veterans. Chest 2006; 130:1326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92:2506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:1593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93:3499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PS et al. Incidence of types of cancer among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population in the United States, 1992–2003. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148:728–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC et al. HIV infection and the risk of diabetes mellitus. AIDS 2009; 23:1227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverberg MJ, Chao C, Leyden WA et al. HIV infection and the risk of cancers with and without a known infectious cause. AIDS 2009; 23:2337–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS 2010; 24:1228–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salter ML, Lau B, Go VF et al. HIV infection, immune suppression, and uncontrolled viremia are associated with increased multimorbidity among aging injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:1256–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:1120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1787–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tripathi A, Liese AD, Jerrell JM et al. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort of HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected persons: the impact of clinical and therapeutic factors over time. Diabet Med 2014; 31:1185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene M, Steinman MA, McNicholl IR, Valcour V. Polypharmacy, drug-drug interactions, and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall CE, Wong J, Taljaard M et al. A cross-sectional, population-based study measuring comorbidity among people living with HIV in Ontario. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen LD, Helleberg M, May MT et al. Myocardial infarction among Danish HIV-infected individuals: population-attributable fractions associated with smoking. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Althoff KN, McGinnis KA, Wyatt CM et al. Comparison of risk and age at diagnosis of myocardial infarction, end-stage renal disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancer in HIV-infected versus uninfected adults. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoeni-Affolter F, Ledergerber B, Rickenbach M et al. Cohort profile: the Swiss HIV Cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39:1179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friis-Moller N, Sabin CA, Weber R et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:1993–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Firmann M, Mayor V, Vidal PM et al. The CoLaus study: a population-based study to investigate the epidemiology and genetic determinants of cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2008; 8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chmiel C, Bhend H, Senn O et al. The FIRE project: a milestone for research in primary care in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2011; 140:w13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamers LM, van Vliet RC. The Pharmacy-based Cost Group model: validating and adjusting the classification of medications for chronic conditions to the Dutch situation. Health Policy 2004; 68:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) ATC/DDD Index 2014. Available at: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index Accessed 21 August 2014.

- 29.Zellweger U, Bopp M, Holzer BM et al. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions in Switzerland: exploring estimates validity by comparing complementary data sources. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2006; 145:247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consultation WHOE. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabin CA, Ryom L, Kovari H et al. Association between ALT level and the rate of cardio/cerebrovascular events in HIV-positive individuals: the D:A:D study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63:456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 2013; 382:1525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovari H, Sabin CA, Ledergerber B et al. Antiretroviral drug-related liver mortality among HIV-positive persons in the absence of hepatitis B or C virus coinfection: the data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs study. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:870–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.