Abstract

A 28-year-old man developed asthma 10 years after working in a metal-plating factory. Recordings of peak expiratory flow rates showed increased variations after exposure at work. Allergy prick skin tests elicited an immediate reaction with nickel sulfate at a concentration of 1 and 10 mg/ml, and with zinc sulfate at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. Inhalation challenges with nickel sulfate and zinc sulfate produced bronchial obstructions. Thus, we concluded that this was a case of asthma caused by nickel sulfate and zinc sulfate.

Keywords: Occupational asthma, Nickel sulfate, Zinc sulfate

INTRODUCTION

Asthma caused by nickel sulfate (NiSO4) seems to be a rare phenomenon. Zinc has been suspected to cause respiratory symptoms, but there is little clinical data on the role of zinc in the allergic respiratory disease of man. We are reporting a case of asthma which has been proven to have resulted from exposure to nickel sulfate and zinc sulfate.

CASE

A 28-year-old man visited the allergy clinic at Severance Hospital in July 1980, complaining of a nonproductive cough and dyspnea of three months duration.

Past medical history was unremarkable. He had stopped smoking 2 weeks prior to his visit to the clinic. Neither he nor his family had history of allergy. The patient had worked in a metal-plating factory since the age of 18 years. His job was to treat rusted metals with aqua regia and to electroplate metals.

Since May of 1980, he had noticed a non-productive cough and chest tightness. The symptoms occurred usually at night and persisted for 2–3 hours. By morning his cough had abated. During work, he noted only a mild cough. On Sunday nights his symptom was much milder than on weekday nights. He had not experienced these symptoms previously. Dyspnea and wheezing sounds had been noted since a severe coughing attack in July 1980.

Physical examination findings on his lungs, heart, and skin were unremarkable. His peripheral eosinophil count was 500/mm3, and serum level of total IgE was 420 u/ml (PRIST). Findings on a chest roentgenogram were negative. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was 3.68 L (88% of predicted value): forced midexpiratory flow F E F 25–75%), 3.82 L (88%); and forced vital capacity (FVC), 4.21 L (79%). Methacholine bronchial threshold was 250 units. He was instructed to change his job, and after doing so, he was in a symptom-free state for three years.

From August of 1983 he started to work at the same job again, at the same metal-plating factory. Seven months later, chest symptoms recurred. In May 1984 he visited our clinic again.

During the previous one month he had noted severe cough and dyspnea every night. When he was out of work for several days, the nocturnal chest symptoms did not occur.

Again, physical examination findings on his lungs, heart, and skin were unremarkable. His peripheral eosinophil count was 2753/mm3. Total IgE level was 4035 u/mL. FEV1 was 4.01 L (96% of predicted); FEF25–75% 4.25 L (104%); and FVC 4.48 L (84%). Methacholine bronchial threshold was 49.5 units (PC20M of 2.8 mg/mL).

These findiangs in the history and laboratory data strongly suggested that his asthma was related to his work environment, and further investigations were carried out.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Allergens

Eighty allergens from the Bencard (England) and Torii (Japan) Company were used for a skin prick test. Nickel sulfate and zinc sulfate were prepared in sterile saline in concentrations of 10 and 1 mg/ml, for the purpose of skin testing and inhalation challenge.

2. Measurement of Allergen-specific IgE

The specific IgE of house dust and house dust mites were measured using the Phadebas RAST kit.

3. Monitoring of Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR)

The patient was given a Wright peak flow meter in order to obtain a record of the change in his PEFR during and after occupational exposure.

4. Provocation Tests

A bronchial provocation test (BPT) was performed after inhalations of house dust extract (Torii, Japan) with Vaponephrine nebulizer (Nihon Shyojii, Japan) at 6 L/min of compressed air. Serial pulmonary function tests were done 10 minutes after five inhalations of diluted (1:500, 1:100 & 1:50 w/v by normal saline) and nondiluted (1:10 w/v) solutions of house dust extract by FVC breathing.

The changes on the pulmonary function test were also serially recorded after inhalation of chemical fumes for five minutes on tidal volume breathing, which vaporized from aqua regia applied to a copper coin.

Specific inhalation challenges with NiSO4 and ZnSO4 were performed with a Vaponephrine nebulizer.

The decrease in FEV1 of less than 15% with respect to the control value was defined as a negative result for BPT.

RESULTS

The results of the skin prick test for eighty allergens were 3+ for housedust, 2+ for Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, 2+ for D. farinae, 1+ for household insects, 1+ for cat epidermals, 3+ for trichophyton, and 2+ for sporobolomyces. RAST of house dust and dust mites were negative.

The BPT response with house dust extract was negative for nine hours after two challenges of undiluted allergen extract (Torii, therapeutic use, 1:10 w/v).

The results of BPT with chemical fumes, from aqua regia was also negative for eight hours after challenge, even though vapored yellow gas induced coughing in medical personnel and the patient being tested.

Figure 1 shows the variations of PEFR after exposure to the usual working conditions. Before re-exposure he had postponed returning to work for 3 weeks since the latest attack of asthma had developed. Initial PEFR on the Wright peak flow meter was 505 L/min. The percentage fall of PEFR was 13% one hour after finishing work on the first day and 25% at midnight after the second working day.

Fig. 1.

Monitoring of PEFR after occupational exposure. Initial PEFR was 505 L/min. The percentage fall of PEFR was 25% at midnight after the second working day.

The patient was evaluated for reaction to nickel sulfate and zinc sulfate in September 1984. He reacted, on skin prick test, to nickel sulfate solution (1 mg/ml, 4 × 4 mm of wheal; 10 mg/mL, 6 × 6 mm) and zinc sulfate solution (1 mg/ml, negative; 10 mg/ml, 5 × 5 mm). In the control subjects, the results of the skin tests with nickel sulfate solution and zinc sulfate solution were negative.

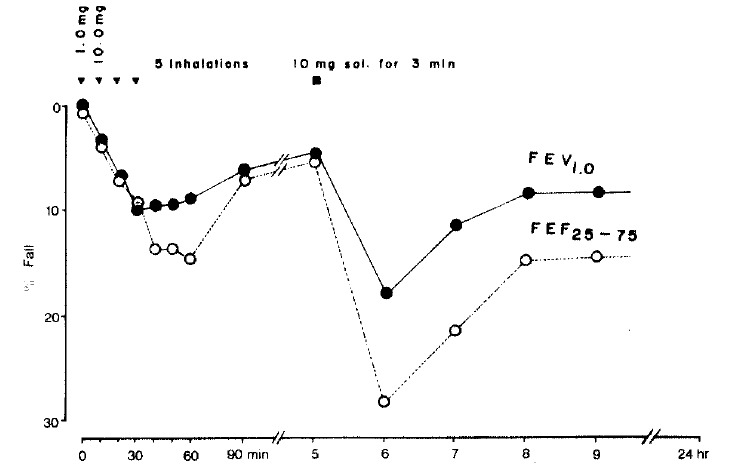

The result of nickel sulfate bronchoprovocation tests are shown in figure 2. Inhalation of normal saline resulted in no significant change of FEV1. Three challenges of 10 mg/ml of nickel sulfate solution (inhaled by FVC breathing 5 times) showed a 10% decrease in FEV1. Four hours later he inhaled a 10 mg/ml solution for 3 minutes by tidal volume breathing. Ten minutes later he felt a mild tightness in his chest and coughed. One hour later, the percentage fall in FEV1 was 18%, and the percentage fall in FEF25–75% was 28%, which demonstrated that pulmonary function had progressively improved. On the morning of the following day, pulmonary function had returned to the initial level.

Fig. 2.

BPT with nickel sulfate. Eighteen percent fall of FEV1 and 28% fall of FEF25–75% were noted one hour after inhalation of 10 mg/ml solution for three minutes by tidal volume breathing.

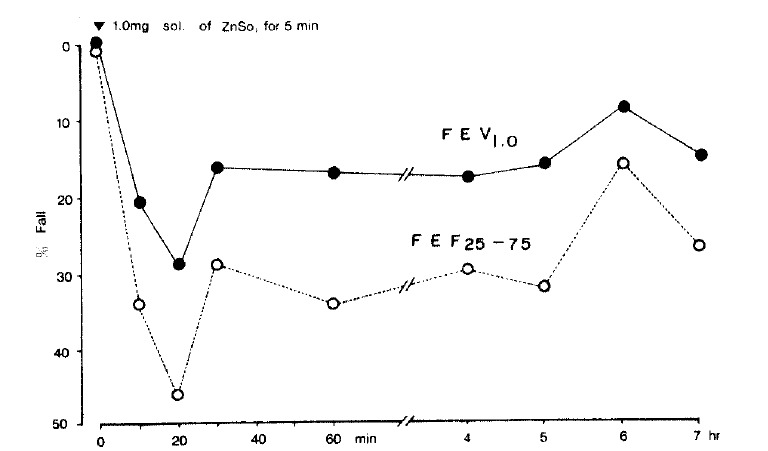

Figure 3 shows early bronchoconstriction response after inhalation of a 1 mg/ml solution of zinc sulfate for five minutes by tidal volume breathing. The bronchoconstriction induced by zinc sulfate persisted for seven hours after the challenge.

Fig. 3.

BPT with zinc sulfate. Early bronchoconstriction response was noted after inhalation of 1 mg/ml solution for five minutes by tidal volume breathing. The induced bronchoconstriction persisted for seven hours after the challenge.

DISCUSSION

Nickel is widely used in industry and has been long recognized as an inducer of contact dermatitis. Asthma due to the inhalation of and sensitization to nickel sulfate has been reported1–4). In patients with bronchial asthma induced by nickel, skin testing for nickel sulfate demonstrated an immediate wheal-and-flare skin reaction, and circulating specific IgE antibodies to nickel could be demonstrated in the patients sera3,4).

These results have suggested that nickel-induced asthma is mediated, in part at least, by an IgE, type I, immunologic mechanism4).

Zinc has been suggested as a cause of respiratory symptoms, although little has been written relating occupational exposure to the occurrence of asthma5).

Our patient showed an immediate bronchoconstriction after the inhalation of nickel sulfate and an immediate bronchoconstriction followed by persistant bronchoconstriction after the inhalation of zinc sulfate. The degree of zinc sulfate solution-induced bronchoconstriction response was much greater than that of nickel sulfate solution induced bronchoconstriction response. This means that his bronchial hyperreactivity to zinc is more severe than that to nickel.

The patient had mainly worked with a zinc electroplating process. He, also, had infrequently worked with a nickel electroplating process. He noted his symptoms only at night, which was confirmed by PEFR monitoring after occupational exposure (Fig. 1).

This suggested that the reason his symptoms occurred at night was that the electroplating was the last part of his work schedule, usually done in the afternoon, and because the concentration of metals (nickel and zinc) in the atmosphere during his other work was at a very low level.

Even though we have not yet confirmed the identity of the specific immunoglobulins in this patient’s serum, it could be concluded that our patient suffered from asthma due to exposure to nickel and zinc at work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Y.H. Kim for her skillful secretorial work and miss A.R. Ahn for her technical assistance in carrying out the BPT s.

REFERENCES

- 1.McConnell LH, Fink JN, Schlueter DP, Schmidt MG. Asthma caused by nickel sensitivity. Ann Intern Med. 1973;78:888. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-78-6-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block GT, Yeung M. Asthma induced by nickel. JAMA. 1982;247:1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malo J-L, Cartier A, Doepner M, Nieboer E, Evans S, Dolovich J. Occupational asthma caused by nickel sulfate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;69:55. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novey HS, Habib M, Well ID. Asthma and IgE antibodies induced by chromium and nickel salts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;72:407. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink JN. Occupational asthma from inorganic chemicals. Clinic in Immunology and Allergy. 1984;4:125. [Google Scholar]