Abstract

Purpose of review

Progressive organ fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) are the leading causes of death in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). However, the pathogenesis and the link between these two processes remain obscure. A better understanding of these events is needed in order to facilitate the discovery and development of effective therapies for SSc.

Recent findings

Recent reports provide evidence that the orphan receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), better known for its pivotal role in metabolism, has potent effects on inflammation, fibrogenesis and vascular remodeling and is important in the pathogenesis of fibrosis and PAH, and as a potential therapeutic target in SSc. The studies discussed in this review indicate that ligands of PPARγ potently modulate connective tissue turnover and suggest that aberrant expression or function of PPARγ is associated with, and very likely contributes to, the progression of pathological fibrosis and vascular remodeling. These observations are of particularly relevance because FDA-approved drugs of the thiazolidinedione class currently used for the treatment of obesity-associated type 2 diabetes activate PPARγ signaling. Moreover, novel PPARγ ligands with selective activity are under development or in clinical trials for inflammatory diseases, asthma, Alzheimer disease and cancer.

Summary

Drugs targeting the PPARγ pathway might be effective for the control of fibrosis as well as pathological vascular remodeling underlying PAH and, therefore, might have a therapeutic potential in SSc. A greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying the antifibrogenic and vascular remodeling activities of PPARγ ligands will be necessary in order to advance these drugs into clinical use.

Keywords: fibroblast, fibrosis, fibrosis therapy, myofibroblast, pulmonary arterial hypertension, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, scleroderma, transforming growth factor β

Introduction

It is thought that chemical, infectious, mechanical or autoimmune injury in a genetically susceptible host triggers persistent fibroblast activation and myofibroblast transdifferentiation that underlie pathological fibrosis. Injury can also cause transdifferentiation of epithelial cells into activated myofibroblasts through a process called epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). Endothelial cells, preadipocytes and vascular pericytes can also trans-differentiate into myofibroblasts. These cellular transitions are regulated by a variety of factors, of which transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and Wnt are most prominent. Activated myofibroblasts accumulate in the damaged tissue, where they engage in sustained matrix synthesis, resulting in excessive connective tissue accumulation and remodeling and buildup of intractable scar. Agents that block mesenchymal cell activation and transdifferentiation might be effective in controlling fibrosis.

The peroxisome proliferator-activated γ in physiology and disease

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is an orphan receptor that belongs to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, members of which function as ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate a broad range of physiological responses [1•]. The three distinct isoforms of PPAR (PPARα, PPARβ/δ, PPARγ) are encoded by three genes. PPARγ itself exists in two isoforms, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2, which are the products of the same gene derived by differential transcription start site usage [2].

The expression level of PPARγ in a given cell or tissue determines the intensity and duration of the cellular response to endogenous or synthetic PPARγ ligands. In light of PPARγ’s pleiotropic physiological roles, the level of PPARγ expression could have an important modulating influence on a variety of homeostatic responses. Surprisingly, little is known regarding the factors that regulate the expression of PPARγ. It is worth noting, however, that cytokines implicated in fibrosis generally suppress PPARγ expression in mesenchymal effector cells (J. Wei, A.K. Ghosh, J.L. Sargent, et al., submitted for publication). TGF-β is a potent inhibitor of PPARγ expression in fibroblasts, but not in macrophages (J. Wei, A.K. Ghosh, J.L. Sargent, et al., submitted for publication). Other inhibitors of PPARγ expression include interleukin-13 (IL-13), Wnt, CCN2, leptin, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and hypoxia [3–6]. MicroRNA miR-27b is also a potent inhibitor of adipocyte differentiation via targeting PPARγ. Moreover, cellular levels of PPARγ are also regulated through proteasomal degradation. On the contrary, adiponectin, which is itself regulated by PPARγ, enhances the expression of PPARγ in the liver and adipose tissue. Serum adiponectin might therefore be a potential biomarker of the level of PPARγ expression and progression of fibrosis in SSc (see below).

In unstimulated cells, the PPAR receptors reside in the cytoplasm as heterodimers complexed to their repressors. Upon activation by ligands, the PPARs undergo a conformational change allowing recruitment of retinoid X receptor (RXR) coactivators and the RXR–PPAR complex is then translocated into the nucleus, where it binds to conserved PPRE DNA elements in target gene promoters, resulting in induction, or less commonly repression, of transcription.

PPARγ was originally identified in fat, but is now known to be widely expressed in immune cells such as macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, as well as platelets, epithelial and endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts [7]. Tissues rich in PPARγ include visceral and subcutaneous fat, along with colon, spleen, liver, skeletal muscle, bone marrow and lung [8]. Initial studies identified a pivotal role for PPARγ in lipid metabolism and adipogenesis by inducing the expression of multiple target genes such as adiponectin and FABP4 [9]. It was subsequently shown that PPARγ is important in regulation of glucose homeostasis. Recent attention has focused on the role of PPARγ in inflammation, cell proliferation and apoptosis, and it is now clear that PPARγ modulates diverse physiologic responses and is implicated in myriad disorders. Homozygous germline deletion of PPARγ in the mouse results in embryonic lethality due to defective placental development [10]. Tissue-specific conditional deletion of PPARγ is associated with substantial disorder, including spontaneous pulmonary hypertension in mice with loss of PPARγ in the endothelium or vascular smooth muscle cells [11•,12]. The physiological importance of PPARγ is further underlined by the range of human disorders that are associated with altered PPARγ expression or function. Prominent examples include type 2 diabetes, lipodystrophy, the metabolic syndrome, as well as osteopenia, pulmonary hypertension, ulcerative colitis and inflammatory conditions. Recent studies indicate that SSc is also associated with altered PPARγ biology. Allelic polymorphisms in the PPARγ gene are associated with type 2 diabetes, obesity, asthma and cardiovascular disease, and dominant negative PPARγ mutations cause lipodystrophy and diabetes [13].

Natural and synthetic ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

The importance of PPARγ became apparent in 1995, when it was identified as the cellular receptor for the thiazolidinedione class of antidiabetic drugs such as rosiglitazone and pioglitazone [14]. The antidiabetic efficacy of thiazolidinediones depends on induction of PPARγ target genes mediating lipid and glucose metabolism [15]. Although the ‘true’ endogenous ligand for PPARγ remains unknown [3], multiple naturally occurring compounds such as fatty acids, prostaglandin D-derived 15deoxy-12,14 prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) and LPA can activate PPARγ in a variety of cell types [16]. It is very likely that there exist additional as-yet unidentified natural PPARγ ligands that maintain basal or constitutive PPARγ signaling. Synthetic ligands of PPARγ include, in addition to thiazolidinediones, triterpenoid compounds derived from oleanic acid [17]. The clinical utility of thiazolidinediones is limited by side-effects including weight gain, fluid retention, osteopenia and bone fractures and, possibly, congestive heart failure [18]. The risk of cardiovascular events may also be increased in diabetic patients treated with thiazolidinediones, particularly in women, although a recent study [4] showed no increase. Strategies for safer insulin-sensitizer drugs involve the development of selective PPARγ modulators (SPPARMs) with partial or gene-selective agonist activities or augmenting the expression of PPARγ [19•]. A promising novel compound is CDDO, a stable orally active triterpenoid that has both PPARγ-dependent and PPARγ-independent biological activities while causing only modest adipogenic gene expression [20•]. CDDO inhibits cell proliferation and inflammatory mediator synthesis and is currently used under the name bardoxolone in clinical trials for diabetic kidney disease and cancer.

Relevant biological functions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

In addition to its importance in lipid and glucose metabolism, PPARγ plays a role in controlling cell proliferation and differentiation. PPARγ ligands have potent effects on bone metabolism, inflammation and tissue repair. Mice with conditional deletion of PPARγ in adipose tissue develop lipoatrophy, and patients with dominant negative PPARγ mutations develop lipodystrophy [21,22]. The disappearance of the subcutaneous adipose layer in these conditions resembles the subcutaneous changes observed in murine models of scleroderma [23]. Subcutaneous adipose tissue atrophy is also prominent in biopsies from patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc.

An important role for PPARγ in broadly regulating inflammation and immunity is emerging. Rosiglitazone, by activating PPARγ, caused potent inhibition of macrophage activation [24]. The anti-inflammatory effect of PPARγ ligands is associated with reduced production of inflammatory mediators including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and chemokines, but the precise molecular mechanisms underlying suppression remain to be fully elucidated. A recent study [25] reported that rosiglitazone attenuated the stimulation of CXCL10 secretion in explanted SSc fibroblasts. In vivo, PPARγ ligands ameliorated allergic airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma [26] and reduced the severity of disease manifestations in a mouse model of cystic fibrosis associated with inflammation [27]. Activation of PPARγ also disrupts Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated innate immune responses [28]. The ability of PPARγ to suppress inflammation and innate immunity has important therapeutic implications [29].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and fibrosis

Recent studies employing in-vitro and in-vivo approaches have revealed an entirely novel role for PPARγ in fibrogenesis. This was initially recognized by Hazra et al. [30], who observed that ectopic PPARγ expression in activated hepatic stellate cells induced a phenotypic switch of these cells to quiescence. The switch is associated with suppression of type I collagen gene expression. Moreover, activation of cellular PPARγ receptors using either synthetic or natural PPARγ ligands blocks the induction of profibrotic responses in vitro. For instance, treatment of normal skin and lung fibroblasts with PGJ2 or rosiglitazone was found to abrogate TGF-β-induced stimulation of collagen and fibronectin synthesis, myofibroblast differentiation, fibroblast migration and the secretion of fibrotic growth factors such as TGF-β and CTGF [31,32]. Moreover, rosiglitazone attenuated the persistently activated phenotype of lesional skin fibroblasts explanted from patients with SSc [33]. Rosiglitazone also prevented differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells into fibroblasts and, instead, promoted their differentiation into adipocytes. These observations are entirely consistent with the well documented adipogenic potential of PPARγ [34,35]. Remarkably, PPARγ ligands also inhibited alveolar epithelial cells–mesenchymal transition induced by TGF-β, highlighting the regulation of cell differentiation as a fundamental mechanism underlying the antifibrogenic activities of PPARγ ligands [36]. In rodents, PPARγ ligands ameliorated carbon tetrachloride or choline deficient diet-induced liver fibrosis. Rosiglitazone attenuated cardiac fibrosis and diabetic renal fibrosis and prevented chronic damage in a renal allograft model [37]. Troglitazone, an older PPARγ ligand, attenuated lung fibrosis induced by intratracheal bleomycin installation, even when treatment was delayed [38]. In a mouse model of scleroderma induced by daily bleomycin injections, rosiglitazone both prevented and attenuated skin fibrosis [39•]. It is likely that the striking protection from fibrosis afforded by PPARγ ligands in these rodent models is due, at least in part, to their immunosuppressive effects as well as direct antifibrogenic effects. There is a suggestion that thiazolidinedione treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes delays and prevents the progression of chronic kidney disease [40].

How do peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands block fibrogenic responses?

The molecular mechanisms underlying the antifibrotic effects of PPARγ are the subject of intense investigation. In normal fibroblasts, ligand-activated PPARγ blocks profibrotic signaling triggered by TGF-β and Wnt-β-catenin and interferes with downstream signal transduction [31,41•]. In the case of TGF-β-mediated fibroblast activation, PPARγ does not prevent Smad2/3 phosphorylation or nuclear accumulation, but, instead, prevents recruitment of the p300 to the transcriptional complex [42,43]. p300 is an obligate coactivator required for Smad-dependent collagen gene transcription. Because p300 acts via histone acetylation, the findings imply that PPARγ ligands suppress fibrotic gene expression via epigenetic regulation. In contrast to fibroblasts, treatment of hepatic stellate cells with PPARγ ligands was shown to block TGF-β-induced Smad3 phosphorylation, suggesting that the antagonistic effects of PPARγ ligands on TGF-β signal transduction may involve distinct cell type-specific mechanisms [44]. Other studies showed that PPARγ ligands stimulated hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), an endogenous antifibrotic agent that then mediates autocrine suppression of TGF-β-induced fibrogenic responses [45]. Finally, PPARγ ligands have been shown to block the induction of Egr-1, an early-immediate transcription factor that plays a fundamental role in transducting fibrogenic activities triggered by TGF-β and other cytokines [39•,46]. The antifibrotic effects triggered by PPARγ ligands, including inhibition of fibroblast migration, adipocyte differentiation and myofibroblast transition, might also involve PPARγ-independent pathways.

An alternate mechanism to account for the antifibrogenic effects of PPARγ ligands has been proposed. This model involves PPARγ-mediated stimulation of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN). PTEN abrogates the stimulation of collagen production and myofibroblasts differentiation in normal fibroblasts [47]. Studies have shown that the expression of PTEN is deficient in pulmonary fibrosis and in lesional SSc skin, and PTEN has been implicated as a causative agent in the progression of fibrosis [48,49]. Pharmacological stimulation of PTEN in these conditions using PPARγ ligands may be a potential therapeutic approach in fibrosis [47].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression in fibrosis

It was observed that in the resolution phase of wound healing, there is a switch from pro-inflammatory prostaglandin production to PGJ2 and PPARγ in the skin, suggesting that a physiologic role of PPARγ might be the negative regulation of matrix remodeling [50]. Indeed, an inverse relationship between fibrosis and PPARγ expression and function has been noted in multiple human fibrosing disorders as well as in rodent models of fibrosis. However, it is not immediately obvious whether fibrosis in these conditions is the cause of reduced PPARγ, or the other way around, that is, reduced PPARγ causes fibrosis. Reduced PPARγ tissue levels have been found in fibrosis of the kidney [51], liver [52] and lungs [53], in SSc-associated pulmonary fibrosis (J. Wei, A.K. Ghosh, J.L. Sargent, et al., submitted for publication), and associated with scarring alopecia in the scalp [54]. Fibroblasts explanted from lesional SSc skin show reduced PPARγ expression, although curiously they retain sensitivity to PPARγ ligand-induced suppression of collagen production and alpha smooth muscle actin expression [33]. Moreover, PPARγ in various tissues shows reduced expression with aging [55]. The development of skin fibrosis in bleomycin-induced scleroderma in the mouse is accompanied by a decline in cutaneous PPARγ levels [39•]. Microarray-based transcriptional profiling in SSc showed reduced PPARγ expression and function in patient biopsies with a robust TGF-β-activated gene expression signature (J. Wei, A.K. Ghosh, J.L. Sargent, et al., submitted for publication). These biopsies showed reduced expression of PPARγ target genes involved in adipogenesis and fat metabolism including PGC1, PCK1 and FABP2. The same biopsies also showed reduced expression of PTEN. Moreover, there was a trend toward lower PPARγ expression in patients with more extensive skin involvement.

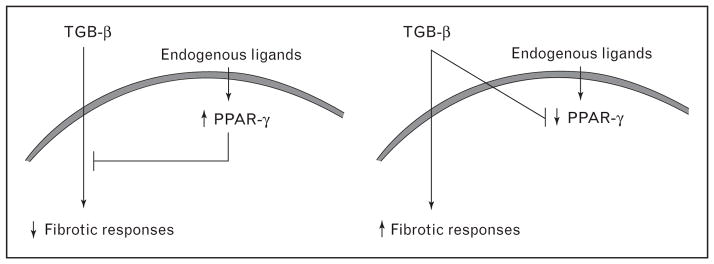

The existence of an inverse relationship between PPARγ expression levels and fibrogenesis indicates a potential physiologic function of PPARγ in affording protection from excessive fibrogenesis (Fig. 1). Consistent with this predicted homeostatic role for PPARγ, inhibition of its expression or function is causally linked to the development of fibrosis in mouse models. For example, conditional knockout of the PPARγ gene targeted to follicular stem cells in the scalp is associated with scarring [54]. Fibroblast-specific deletion of PPARγ in the mouse resulted in enhanced sensitivity to the fibrogenic effects of bleomycin [56]. Mice harboring a dominant negative human PPARγ gene mutation develop exaggerated cardiac fibrosis when challenged with angiotensin II [57].

Figure 1. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ signaling calibrates fibrogenic responses.

Under physiologic conditions, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) shows a low level of constitutive activation, driven by natural ligands controlling fibrotic responses (left panel). Prolonged or recurrent fibrogenic stimulation due to injury (right panel) suppresses the expression of PPARγ expression, reducing cellular responsiveness to natural endogenous PPARγ ligands. This leads to unopposed stimulation of collagen synthesis and myofibroblast differentiation by fibrogenic stimuli such as TGF-β, resulting in progressive fibrosis.

Reduced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression and function in pulmonary arterial hypertension

Previous studies have noted reduced PPARγ expression in the lungs from patients with PAH [58]. Remarkably, in the mouse, targeted knockout of PPARγ in pulmonary vessels resulted in the spontaneous development of PAH, right ventricle hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodeling [11•,12]. This was associated with marked upregulation of platelet-derived growth factor signaling in the blood vessels that could be abrogated by treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, New Jersey, USA). Moreover, hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in the mouse was attenuated by rosiglitazone [59]. Therefore, PPARγ appears to be important for pulmonary vascular homeostasis, and reduced PPARγ expression or function leads to PAH [60]. It is remarkable, therefore, that defective PPARγ expression or function appears to be implicated in the pathogenesis of both fibrosis and PAH, two of the lethal complications of SSc, and, at least in experimental models, both of these PPARγ-associated pathological processes could be ameliorated with PPARγ ligands. These findings raise hope that pharmacological PPARγ modulation might be an effective therapeutic strategy in SSc targeting both fibrotic and vascular disorders.

Conclusion

The multifunctional nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ is beginning to emerge as a regulatory molecule of great interest in the pathogenesis and treatment of fibrosis in general and SSc in particular. Recent publications point to PPARγ as a hitherto unsuspected nexus between metabolism and pathological fibrosis and vascular remodeling. Substantial evidence from several human diseases and animal models indicates that on the one hand, there exists a causal relationship between fibrosis and pulmonary vascular disease and reduced PPARγ expression and function, and on the other hand, pharmacological targeting of PPARγ might be able to prevent and even reverse fibrosis and vascular remodeling and pulmonary arterial hypertension (Fig. 1). Several PPARγ ligands currently used in type 2 diabetes therapy are orally active and relatively well tolerated and could, therefore, be evaluated in patients with SSc. A precise understanding of the cellular mechanisms of action underlying the antifibrogenic and vascular remodeling activities of these PPARγ ligands is needed. Moreover, it will be of great interest to investigate the genetic associations between PPARγ gene polymorphisms and SSc and specific SSc disease phenotypes such as pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the NIH and the Scleroderma Research Foundation.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (p. 709).

- 1•.McKenna NJ, Cooney AJ, DeMayo FJ, et al. Evolution of NURSA, the Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:740–746. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0135. A useful up-to-date review of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that includes PPARγ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans RM, Barish GD, Wang YX. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat Med. 2004;10:355–361. doi: 10.1038/nm1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yun Z, Maecker HL, Johnson RS, Giaccia AJ. Inhibition of PPAR gamma 2 gene expression by the HIF-1-regulated gene DEC1/Stra13: a mechanism for regulation of adipogenesis by hypoxia. Dev Cell. 2002;2:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Kimura H, Hirota K, et al. Hypoxia reduces the expression and anti-inflammatory effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in human proximal renal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1041–1051. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan JT, McLennan SV, Song WW, et al. Connective tissue growth factor inhibits adipocyte differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C740–C751. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00333.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakatos HF, Thatcher TH, Kottmann RM, et al. The role of PPARs in lung fibrosis. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:71323. doi: 10.1155/2007/71323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahli W, Braissant O, Desvergne B. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors: transcriptional regulators of adipogenesis, lipid metabolism and more [review] Chem Biol. 1995;2:261–266. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The many faces of PPAR-γ. Cell. 2005;123:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, et al. PPAR γ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Guignabert C, Alvira CM, Alastalo TP, et al. Tie2-mediated loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in mice causes PDGF receptor-beta-dependent pulmonary arterial muscularization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1082–L1090. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00199.2009. This study established a critical negative regulatory role for endothelial PPARγ expression in maintaining vascular homeostasis in the lung. Tie-mediated deletion of PPARγ in endothelial cells was associated with the spontaneous development of pulmonary hypertension in the mouse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansmann G, de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, et al. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1846–1857. doi: 10.1172/JCI32503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeninga EH, Gurnell M, Kalkhoven E. Functional implications of genetic variation in human PPARgamma. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegelman BM. PPAR-gamma: adipogenic regulator and thiazolidinedione receptor. Diabetes. 1998;47:507–514. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yki-Järvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1106–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McIntyre TM, Pontsler AV, Silva AR, et al. Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARgamma agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135855100. Erratum in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003 18; 100:2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Place AE, Suh N, Williams CR, et al. The novel synthetic triterpenoid, CDDO-imidazolide, inhibits inflammatory response and tumor growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2798–2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nissen SE. Setting the RECORD straight. JAMA. 2010;303:1194–1195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Higgins LS, Depaoli AM. Selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) modulation as a strategy for safer therapeutic PPAR-gamma activation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:267S–272S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28449E. An up-to-date review of the development of novel PPARγ ligands with selective agonist activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Ferguson HE, Thatcher TH, Olsen KC, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands induce heme oxygenase-1 in lung fibroblasts by a PPARgamma-independent, glutathione-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L912–L919. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00148.2009. This study investigates the cellular mechanisms underlying the antifibrotic activities elicited by PPARγ ligands. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, et al. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savage DB, Tan GD, Acerini CL, et al. Human metabolic syndrome resulting from dominant-negative mutations in the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Diabetes. 2003;52:910–917. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu M, Varga J. In perspective: murine models of scleroderma. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:173–182. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chawla A, Barak Y, Nagy L, et al. PPAR-γ dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat Med. 2001;7:48–52. doi: 10.1038/83336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonelli A, Ferri C, Ferrari SM, et al. Induction of CXCL10 secretion by IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha and its inhibition by PPAR-gamma agonists in cultured scleroderma fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09844.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda K, Marquillies P, Capron M, Dombrowicz D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is expressed in airways and inhibits features of airway remodeling in a mouse asthma model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:882–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harmon GS, Dumlao DS, Ng DT, et al. Pharmacological correction of a defect in PPAR-gamma signaling ameliorates disease severity in Cftr-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2010;16:313–318. doi: 10.1038/nm.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dasu MR, Park S, Devaraj S, Jialal I. Pioglitazone inhibits Toll-like receptor expression and activity in human monocytes and db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3457–3464. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glass CK, Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hazra S, Xiong S, Wang J, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma induces a phenotypic switch from activated to quiescent hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11392–11401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharyya S, Lakos G, et al. Disruption of transforming growth factor beta signaling and profibrotic responses in normal skin fibroblasts by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1305–1318. doi: 10.1002/art.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burgess HA, Daugherty LE, Thatcher TH, et al. PPARgamma agonists inhibit TGF-beta induced pulmonary myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production: implications for therapy of lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L1146–L1153. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00383.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi-Wen X, Eastwood M, Stratton RJ, et al. Rosiglitazone alleviates the persistent fibrotic phenotype of lesional skin scleroderma fibroblasts. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:259–263. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, et al. 5-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell. 1995;83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, et al. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan X, Dagher H, Hutton CA, Bourke JE. Effects of PPAR gamma ligands on TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2010;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiss E, Popovic ZV, Bedke J, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma can inhibit chronic renal allograft damage. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2150–2162. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milam JE, Keshamouni VG, Phan SH, et al. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit profibrotic phenotypes in human lung fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L891–L901. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00333.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Wu M, Melichian DS, Chang E, et al. Rosiglitazone abrogates bleomycin-induced scleroderma and blocks profibrotic responses through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:519–533. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080574. In-vivo study demonstrating that pretreatment of normal mice with the PPARγ ligand rosiglitazone can prevent the development of bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Moreover, PPARγ ligands were effective in ameliorating fibrosis even when treatment was started at the time of maximal inflammation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Zhang D, Li J, et al. Role of PPARgamma in renoprotection in Type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;116:17–26. doi: 10.1042/CS20070462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Lu D, Carson DA. Repression of beta-catenin signaling by PPAR gamma ligands. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;636:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.010. Blocking Wnt signaling might represent another molecular mechanism accounting for the antifibrotic activity of PPARγ ligands. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma abrogates Smad-dependent collagen stimulation by targeting the p300 transcriptional coactivator. FASEB J. 2009;23:2968–2977. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yavrom S, Chen L, Xiong S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma suppresses proximal alpha1(I) collagen promoter via inhibition of p300-facilitated NF-I binding to DNA in hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40650–40659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao C, Chen W, Yang L, et al. PPARgamma agonists prevent TGFbeta1/Smad3-signaling in human hepatic stellate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Wen X, Spataro BC, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is a downstream effector that mediates the antifibrotic action of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:54–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen SJ, Ning H, Ishida W, et al. The early-immediate gene EGR-1 is induced by transforming growth factor-beta and mediates stimulation of collagen gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21183–21197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuwano K. PTEN as a new agent in the fight against fibrogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:5–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2510001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White ES, Atrasz RG, Hu B, et al. Negative regulation of myofibroblast differentiation by PTEN (Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Deleted on chromosome 10) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:112–121. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1058OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bu S, Asano Y, Bujor A, et al. Dihydrosphingosine-1 phosphate has a potent antifibrotic effect in Scleroderma fibroblasts via normalization of PTEN levels. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2117–2126. doi: 10.1002/art.27463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapoor M, Kojima F, Yang L, Crofford LJ. Sequential induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory prostaglandins and peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-gamma during normal wound healing: a time course study. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;76:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng F, Fornoni A, Elliot SJ, et al. Upregulation of type I collagen by TGF-beta in mesangial cells is blocked by PPARgamma activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F639–F648. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00189.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyahara T, Schrum L, Rippe R, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and hepatic stellate cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35715–35722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Culver DA, Barna BP, Raychaudhuri B, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activity is deficient in alveolar macrophages in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:1–5. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0304RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243–1257. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ye P, Zhang XJ, Wang ZJ, Zhang C. Effect of aging on the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the possible relation to insulin resistance. Gerontology. 2006;52:69–75. doi: 10.1159/000090951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapoor M, McCann M, Liu S, et al. Loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in mouse fibroblasts results in increased susceptibility to bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2822–2829. doi: 10.1002/art.24761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kis A, Murdoch C, Zhang M, et al. Defective peroxisomal proliferators activated receptor gamma activity due to dominant-negative mutation synergizes with hypertension to accelerate cardiac fibrosis in mice. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:533–541. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ameshima S, Golpon H, Cool CD, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) expression is decreased in pulmonary hypertension and affects endothelial cell growth. Circ Res. 2003;92:1162–1169. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000073585.50092.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nisbet RE, Bland JM, Kleinhenz DJ, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:482–490. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0132OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hansmann G, Zamanian RT. PPARgamma activation: a potential treatment for pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:12s14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]