An 84-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, and a transient ischemic attack 4 years earlier presented to the University of Illinois at Chicago emergency department for evaluation of 1 day of decreased vision in his left eye. He described it as a central “band” of absent vision just below center. On examination, visual acuity measured 20/40 OD and 20/60 OS, improving to 20/40 with pinhole. A complete blood cell count, results of a comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level, and computed tomography of the head without contrast were all normal. Review of systems was negative. Ocular history included penetrating keratoplasty with intraocular lens exchange and Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty in the right eye. Four days later in the Retina Clinic, visual acuity was unchanged. Slitlamp examination of the anterior segment was normal. Ophthalmoscopy revealed no vitreous cells, a posterior vitreous separation, cup-disc ratio of 0.3, normal retinal vessels, and a superior parafoveal crescent of translucent retina without associated edema or hemorrhage. The peripheral retina was normal. Fundus autofluorescence and fluorescein angiogram showed abnormalities in the superior macula (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

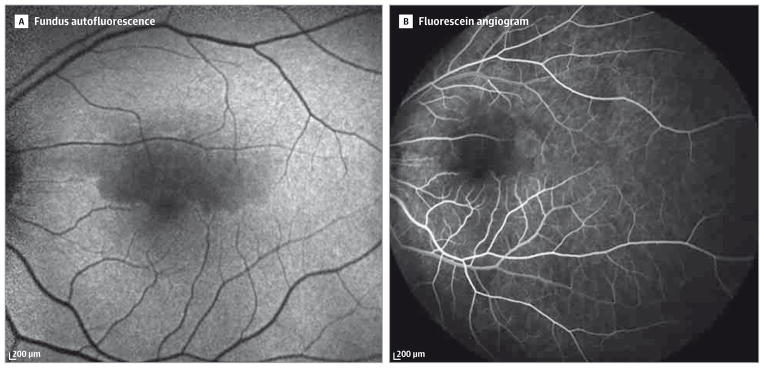

A, Fundus autofluorescence shows a superior parafoveal and perifoveal dark crescent at presentation, corresponding to the hypofluorescent region in part B. B, Fluorescein angiography at presentation revealed delayed perfusion with hypofluorescence in the superior parafoveal and perifoveal regions without leakage.

Diagnosis

Type 1 acute macular neuroretinopathy with features of paracentral acute middle maculopathy

What To Do Next

B. Obtain optical coherence tomography

The differential diagnosis includes branch retinal artery occlusion, age-related macular degeneration, diabetic macularedema, hypertensive retinopathy, acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, central serous chorioretinopathy, and acute macular neuroretinopathy. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) imaging demonstrated inner retina hyperreflectivity in the superior parafoveal and perifoveal region without cystoid spaces or subretinal fluid that became thinner a month later (Figure 2). Fluorescein angiography demonstrated delayed perfusion with hypofluorescence in the superior parafoveal and perifoveal regions. Multimodal imaging revealed a superior parafoveal and perifoveal dark crescent. The patient was diagnosed with type 1 acute macular neuroretinopathy with features of paracentral acute middle maculopathy.

Figure 2.

A, Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the parafoveal macula demonstrated hyperreflective bandlike lesions at the inner nuclear layer at presentation. B, Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the corresponding region in part A shows resolution and relative thinning of the inner nuclear layer 1 month later.

Discussion

Since the first description in 1975, fewer than 100 cases of acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN) have been reported in the literature.1,2 In almost all cases, AMN is associated with mild to moderate loss of vision in one or both eyes. The onset is typically sudden, with patients describing distinct paracentral scotomas with sharp, well-defined margins. These scotomas are congruent with macular lesions visible on funduscopic examination that appear as sharply defined wedge-shaped lesions in a parafoveal distribution, often multiple in number, flat with some overlap, and can be single, multiple, isolated, or oval in appearance.2 Their color depends on the degree of pigment present in the parafoveal macula but typically ranges from dark brown to purple or red.1,2 The pathophysiology of AMN is believed to be related to capillary plexus vasoconstriction orocclusion, which is suggested in this case by delayed capillary parafoveal and perifoveal filling on fluorescein angiography.

Accurate diagnosis of AMN is assisted by high-resolution imaging (SD-OCT, infrared reflectance, and near-infrared autofluorescence) with precise correspondence of macular lesions with paracentral scotomas.3 Oral contraceptive use, influenza-like illness, or recent vasoconstrictor use have been associated with AMN.1,2

On SD-OCT, hyperreflective, bandlike lesions appear below the outer plexiform layer in type 2 AMN and above the outer plexiform layer in type 1 AMN and paracentral acute middle maculopathy (PAMM).4–6 The PAMM lesions, associated with retinal vascular disease, may resolve and lead to retinal thinning and paracentral scotomas.6

Patient Outcome

In summary, our patient was diagnosed with type 1 AMN with features of PAMM. On follow-up examination approximately 1 month later, visual acuity was 20/40 OS, improving to 20/30 with pinhole. The SD-OCT imaging revealed resolution of inner retinal layer hyperintensity with inner retinal layer thinning consistent with the diagnosis (Figure 2).

WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT?

Perform ocular ultrasonography

Obtain optical coherence tomography

Obtain blood tests for vasculitis workup

Administer intravitreal injection of an anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agent

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, core grant EY01792 from the National Eye Institute, and the Marion H. Schenk Chair (Dr Lim).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Bos PJ, Deutman AF. Acute macular neuroretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80(4):573–584. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turbeville SD, Cowan LD, Gass JD. Acute macular neuroretinopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fawzi AA, Pappuru RR, Sarraf D, et al. Acute macular neuroretinopathy. Retina. 2012;32(8):1500–1513. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318263d0c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarraf D, Rahimy E, Fawzi AA, et al. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(10):1275–1287. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsui I, Sarraf D. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy and acute macular neuroretinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2013;44(6 suppl):S33–S35. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20131101-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimy E, Sarraf D. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy spectral-domain optical coherence tomography feature of deep capillary ischemia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(3):207–212. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]