Summary

Small protein ligands can provide superior physiological distribution versus antibodies and improved stability, production, and specific conjugation. Systematic evaluation of the Protein Data Bank identified a scaffold to push the limits of small size and robust evolution of stable, high-affinity ligands: 45-residue T7 phage gene 2 protein (Gp2) contains an α-helix opposite a β-sheet with two adjacent loops amenable to mutation. De novo ligand discovery from 108 mutants and directed evolution towards four targets yielded target-specific binders with affinities as strong as 200 ±100 pM, Tm’s from 65 ±3 °C to 80 ±1 °C, and retained activity after thermal denaturation. For cancer targeting, a Gp2 domain for epidermal growth factor receptor was evolved with 18 ±8 nM affinity, receptor-specific binding, and high thermal stability with refolding. The efficiency of evolving new binding function and the size, affinity, specificity, and stability of evolved domains render Gp2 a uniquely effective ligand scaffold.

Introduction

Molecules that bind targets specifically and with high affinity are useful clinically for imaging, therapeutics, and diagnostics as well as scientifically as reagents for biological modulation, detection, and purification. Antibodies have been successfully used for these applications in many cases, but their drawbacks have instigated a search for alternative protein scaffolds from which improved binding molecules can be developed (Banta et al., 2013; Stern et al., 2013). Biodistribution mechanisms such as extravasation (Schmidt and Wittrup, 2009; Yuan et al., 1995) and tissue penetration (Thurber et al., 2008a, 2008b) are limited by large size (150 kDa for immunoglobulin G, 50 kDa for antigen-binding fragments, and even 27 kDa for single-chain variable fragments) thereby reducing delivery to numerous locales including many solid tumors. Additionally, large size and FcRn-mediated recycling slow plasma clearance (Lobo et al., 2004). While beneficial for minimally toxic molecular therapeutic applications, slow clearance greatly hinders molecular imaging and systemically toxic therapeutics such as radioimmunotherapy (Wu and Senter, 2005) via high background. Smaller agents yield improved results (Natarajan et al., 2013; Orlova et al., 2009; Zahnd et al., 2010). Moreover small size does not preclude therapeutic applications where blocking a protein/protein interaction is required (Fleetwood et al., 2014). As scientific reagents, small size aids synthesis and selective conjugation including protein fusion. Yet significant reduction in scaffold size increases the challenge of balancing evolved intermolecular interaction demands for affinity (Chen et al., 2013; Engh and Bossemeyer, 2002) or function while retaining beneficial intramolecular interactions for stability and solubility.

Protein scaffolds, frameworks upon which numerous functionalities can be independently engineered, offer a consistent source of binding reagents for the multitude of biomarkers and applications thereof (Banta et al., 2013; Sidhu, 2012; Stern et al., 2013). A successful protein scaffold should be efficiently evolvable to contain all of the following properties. High affinity (low-nanomolar dissociation constant) and specificity provide potent delivery (Schmidt and Wittrup, 2009; Zahnd et al., 2010), reduce side effects in clinical applications, and are requisite for precise use in biological study. Stable protein scaffolds provide tolerance to mutations in the search for diverse and improved function (Bloom et al., 2006), resistance to chemical and thermal degradation in production and synthetic manipulation, in vivo integrity to avoid immunogenicity and off-target effects (Hermeling et al., 2004; Rosenberg, 2006), and robustness to harsh washing conditions in vitro. Contrary to the multi-domain architecture of many antibodies and fragments, single domain architecture facilitates production of native ligands as well as incorporation into protein fusions and other multicomponent systems. Cysteine-free structure allows for bacterial production in the reducing E. coli cellular environment, intracellular stability in mammals, and the option of a genetically introduced thiol for site-specific chemical conjugation.

A multitude of alternative protein scaffolds have arisen that possess many of these beneficial properties (Table S1). Fibronectins (11 kDa) (Koide et al., 1998; Lipovsek, 2011), nanobodies (11 kDa) (Revets et al., 2005), designed ankyrin repeat proteins (20 kDa) (Tamaskovic et al., 2012), and anticalins (20 kDa) (Gebauer and Skerra, 2012) have been evolved to interact with numerous targets with high affinity while maintaining stability. However, the relatively large size of these scaffolds leaves room for potential improvement in solid tumor penetration and biodistribution through decreased size. Very small size has been achieved in the case of the cystine knottin scaffold (20–50 amino acids) (Moore et al., 2012) and cyclic peptides (17 amino acids) (Heinis 2009). Knottins often use grafting of known binding motifs, which is only applicable to a subset of targets (Ackerman et al., 2014), although binders have been evolved from naïve libraries (Getz et al., 2011). Peptides, partially due to limited potential for interfacial area as well as the entropic cost of conformational flexibility (Castel et al., 2011), often require extensive optimization to yield the affinity and specificity required for many applications. In addition, the multiple disulfide bonds required for stabilization can complicate production and range of application in both cases. Slightly larger scaffolds, such as Fynomers (63 amino acids) (Grabulovski et al., 2007), affitin (65 amino acids) (Mouratou et al., 2007), or sso7d (63 amino acids) (Gera et al., 2011), have moved closer to the small size of knottins and bicyclic peptides without the need for disulfides. Affibodies (58 amino acids) are the smallest heavily-investigated disulfide-free scaffold in the literature (Löfblom et al., 2010). Their helical paratope has provided high affinity towards many targets; however, they are typically severely destabilized after mutation (midpoint of thermal denaturation (Tm) range: 37–65 °C; median: 46 °C) (Hackel, 2014). There is still space to develop a scaffold that approaches the small size of knottins and peptides, but also possesses the other beneficial properties.

We hypothesized that a thorough exploration of known protein topologies could reveal an effective scaffold that pushed current limits of small size with potential for high affinity and retention of stability. A search of the Protein Data Bank was performed to identify a small protein with characteristics amenable to use as a protein scaffold, including retention of stability upon mutation, lack of disulfides and large available binding surface. Gene 2 protein from T7 phage was selected as the scaffold to investigate further based on the considered characteristics. A library of truncated gene 2 protein (Gp2) mutants was created by diversifying two solvent-exposed loops in the protein. Using yeast surface display and affinity maturation, target-specific Gp2 molecules with nanomolar or better affinity to three model proteins were isolated. The binding proteins retained the wild-type secondary structure characteristics and remained folded up to an average 72 °C. These results verified Gp2 as a promising scaffold for the isolation of strong, specific binders to a wide variety of targets and motivated ligand discovery for the cancer biomarker epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). EGFR is a clinical biomarker for imaging and therapy due to its overexpression in multiple cancer types, including head and neck, breast, bladder, prostate, kidney, colorectal, non-small cell lung cancer and glioma carcinoma (Corcoran and Hanson, 2013; Hynes and MacDonald, 2009). Improved EGFR targeting could empower molecular imaging for patient stratification (Laurent-Puig et al., 2009; Moroni et al., 2005; Scartozzi et al., 2009) and treatment monitoring as well as advanced therapeutics. An EGFR-binding Gp2 was isolated and matured. Binding was verified for membrane-bound EGFR on mammalian cells, and Gp2 was used to detect relative EGFR expression levels across multiple cell lines. The unique combination of small size and efficient evolution of high affinity and stability give Gp2 significant potential for the development of molecular targeting agents.

Results

Scaffold Discovery and Library Construction

The structural information in the Protein Data Bank was surveyed to locate potential binding scaffolds. Based on the efficacy of diversifying loops at one end of a β-sandwich in antibody domains and the type III fibronectin domain, we sought scaffolds with solvent-exposed loops on a β-sheet-rich framework. As two loops can provide sufficient diversity for high affinity binding while a single loop is often insufficient (Lipovsek et al., 2007), we sought protein topologies with two adjacent loops amenable to mutation. All proteins in the Protein Data Bank were filtered to identify single domains of 40–65 amino acids and at least 30% β-sheet content, although the Protein Data Bank filter also anomalously returned several proteins as large as 70 amino acids and with only 25% (β-sheet content. Resultant proteins were visualized in PyMol. Those with two adjoining loops (regions of at least four amino acids without defined secondary structure) and no disulfide bonds were retained. The potential of the diversified loops to provide sufficient binding interface while maintaining a folded protein was assessed via two metrics: (1) solvent accessible surface area of the loop amino acids was calculated using serine as the side chain basis for all diversified sites to avoid wild-type sequence bias; and (2) the average destabilization upon random mutation of the loops was computed using Eris (Yin et al., 2007). Multiple proteins exhibited favorable properties within several categories (Figure 1). One scaffold that performed well on all criteria, especially differentiated by loop orientation, surface area (709 Å2, second highest), and stability (ΔΔGf,mut = 5.6 kcal/mol, third lowest), was selected for focused investigation: T7 phage gene 2 protein (Cámara et al., 2010).

Figure 1. Summary of information for top potential scaffolds.

(A) Structure and proposed paratope surface (red) of top five scoring scaffolds. Images created in Pymol. (B) PDB ID, amino acid length, % β strand, and % α helix, are all from the Protein Data Bank. Loop residues are identified as residues between secondary structural elements. Loop accessible surface area (ASA) is calculated using GetArea after mutating loop residues to serines within PyMol. ΔΔGf;mut was calculated for random loop mutants using Eris. Fibronectin (l ttg) and Affibody (2b88) are included for comparison. Also see Table S1 for commonly used scaffolds.

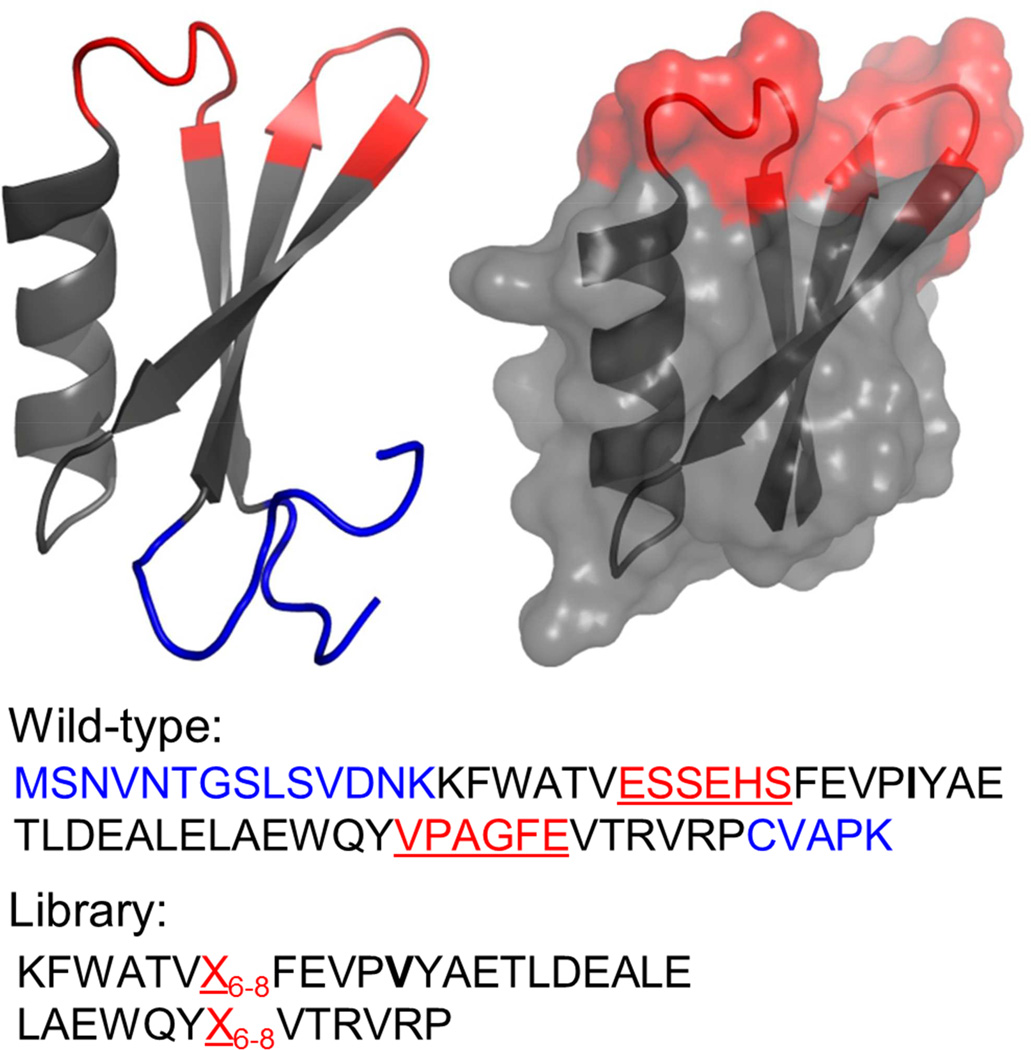

T7 phage gene 2 protein, a 64 amino acid E. coli RNA polymerase inhibitor from T7 phage, was the top protein selected by the ranking system (Figure 2). The coils at the N- and C-termini (14 and 5 amino acids, respectively) were genetically removed to minimize protein size. In addition, a framework mutation (I17V) was made on the basis of 59% frequency in naturally occurring homologs and computational stabilization (ΔΔGf,I→ V = −3.8 kcal/mol via Eris (Yin et al., 2007)). These modifications resulted in the 5.2 kDa, 45 amino acid Gp2 scaffold.

Figure 2. Solution structure of Gp2.

Diversified amino acids are highlighted in red and underlined in sequence. The N- and C- terminal tails removed to create the Gp2 scaffold are highlighted in blue. An I17V (boldface in sequence) mutation was added based on prevalence in homologous protein sequences. Images created in Macpymol (PDB ID: 2wnm).

To evaluate the potential of Gp2 as a protein scaffold for molecular recognition, a combinatorial library of selectively randomized Gp2 sequences was constructed for use in discovery and directed evolution. Two loops, comprising amino acids E7-S12 and V34-E39 (Figure 2), were selected as the proposed binding surface, based on their lack of defined secondary structure, continuous solvent-exposed face, and high solvent-exposed surface area (709 Å2). A yeast surface displayed library, containing approximately 4 × 108 Gp2 molecules based on the number of yeast transformants, was constructed by randomizing 6 amino acids from each loop using amino acid frequencies consistent with antibody complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) (Hackel et al., 2010), and allowing loop length diversity of 6, 7, or 8 amino acids in each loop (Figure 2). Hemagglutinin (HA) and c-myc epitope tags placed upstream and downstream of the Gp2 gene, respectively, allowed for differentiation through flow cytometry of yeast that lost the plasmid (HA−/c-myc−), yeast carrying a plasmid with incomplete Gp2 (HA+/c-myc−) and yeast expressing full-length Gp2 (HA+/c-myc+). A quality control check by flow cytometry indicated that 44% of yeast harboring plasmid expressed full-length Gp2. This was supported through sequencing Gp2 genes, resulting in four full-length Gp2 genes, one Gp2 containing stop codon in the diversified loop and five frame shifted genes. Therefore, the actual size of the library was 1.8 × 108 unique, full-length Gp2 proteins. Amino acid diversity matched the designed distribution (median absolute deviation: 0.5%; Figure S1).

Yeast Surface Display Selection Against Model Protein Targets

Lysozyme and immunoglobulin G (IgG) from rabbit and goat were chosen as the first targets for evaluating the binding potential of the Gp2 scaffold. The differing size and surface topologies of lysozyme (14 kDa) and the IgG proteins (150 kDa) test the scaffold’s ability to target diverse proteins (Diamond, 1974; Harris et al., 1998). The similarity of the two IgG proteins test the ability of Gp2 to create very specific ligands, i.e. binding to goat IgG but not rabbit IgG and vice versa.

During each evolutionary round, the Gp2 library underwent two sorts to enrich specific binders (either with target-coated magnetic beads or through fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)) and one c-myc+ sort to isolate full-length Gp2. Sorted Gp2 sequences were mutated through parallel error-prone PCR reactions targeting the loops or the entire gene and transformed into yeast with loop shuffling driven by homologous recombination (Hackel et al., 2010). After a single maturation cycle, clear binding was evident by flow cytometry for each target campaign (data not shown). Two to four rounds of selection and mutation were carried out for each target to isolate binders with low-nanomolar to picomolar affinity.

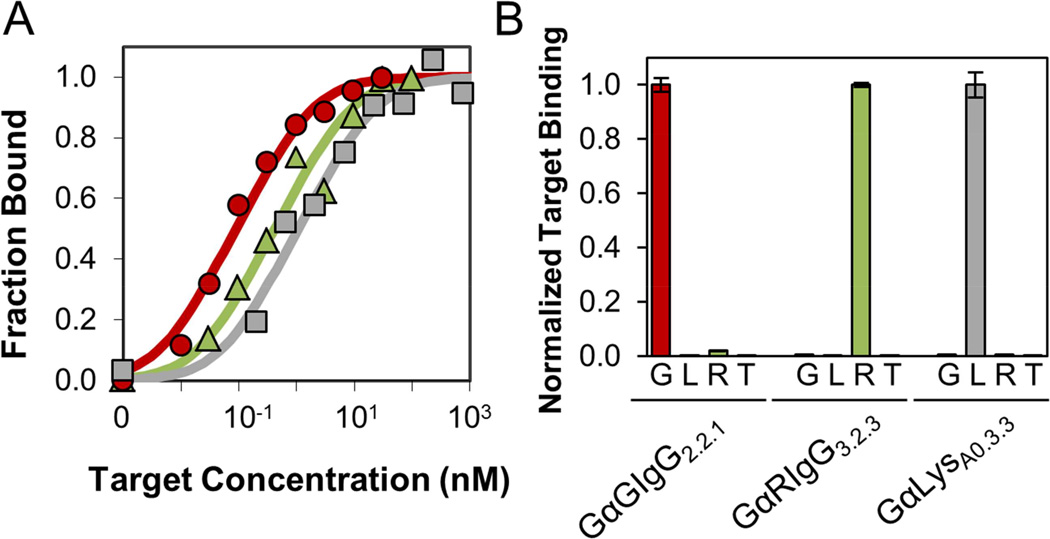

Single clones were isolated at the end of rounds where strong binding was detectable by FACS. Target affinity on the surface of yeast was determined by concentration titration (Table 1 and Figure 3A). Affinities measured on the surface of yeast have been previously shown to match affinities measured by surface plasmon resonance and related techniques (Gai and Wittrup, 2007). The goat IgG binding population contained one dominant sequence family that had affinities as strong as 200 ±100 pM after one mutagenic cycle. The rabbit IgG binding population contained a family of low nanomolar affinity binders at the end of the third mutagenic cycle, which improved to 2.3 ±1.4 nM after another round of affinity maturation. A single dominant clone group was isolated for lysozyme binders after the second round of mutagenesis, albeit with weaker binding. Lysozyme-binding clones isolated in subsequent rounds showed point mutations but no significant increase in binding affinity. A sublibrary was created in which amino acid diversity was chosen based on weighted scores of parental binding sequences, computational stability analysis (using FoldX), natural homolog sequences, and potential for complementarity (Figure S2). The strongest library member isolated was GαLysA0.3.3 with an affinity of 0.9 ±0.7 nM (Figure 3A). During selection and maturation, the lysozyme target was always displayed as a complex with streptavidin. Resultantly, GαLysA0.3.3 bound to a streptavidin-lysozyme complex but not streptavidin or lysozyme alone. Nevertheless, this still supports Gp2 as able to generate specific, high affinity binders to the target presented.

Table 1.

Characterization of wild-type Gp2 and the top binding molecule for each target. Loop 1 and Loop 2 indicate amino acid sequences in the diversified loops (E7-S12 and V34-E39). Framework indicates mutations outside of the loops resulting from error-prone PCR during evolution. Kd values represent equilibrium dissociation constants for clones displayed on the surface of yeast or as purified soluble protein (±SD for n ≥ 3). n.d. indicates data not determined. Tm indicates the midpoint of thermal denaturation as measured by circular dichroism (±SD for n = 2).

| Name | Loop 1 | Loop 2 | Framework | Kd,yeast (nM) | Kd,soluble (nM) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type | ESSEHS | VPAGFE | - | - | - | 67 ± 1 |

| GαGIgG2.2.1 | YDYDADYY | YSNHSDYL | E30V, Q32R | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 70 ± 4 |

| GαLysA0.3.3 | FSYGNL | SGAYEY | - | 0.9 ± 0.7 | n.d. | 65 ± 3 |

| GαRIgG3.2.3 | HSVHGY | GNALGY | E30F, W31G | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 80 ± 1 |

Figure 3. Binding characterization.

(A) Yeast displaying GαGIgG2.2.1 (red circles), GαRIgG3.2.3 (green triangles), and GαLysA0.3.3 (gray squares) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of biotinylated target. Binding was detected by streptavidin-fluorophore via flow cytometry. Titration indicates equilibrium dissociation constants of 0.2 ±0.1 nM, 2.3 ±1.4 nM, and 0.9 ±0.7 nM. (B) Yeast were incubated with 1 µM of goat IgG (G), lysozyme (L), rabbit IgG (R), or transferrin (T). Binding was detected by streptavidin-fluorophore via flow cytometry. Data are normalized to signal of intended target for each yeast strain. Error bars represent ±SD of n = 3 samples. See Figure S3 for full collection of affinity titration curves.

To examine target specificity, the strongest binding ligand from each target campaign was incubated with four proteins at 1 µM. All Gp2 proteins show strong binding to the target protein for which they were selected and matured, while showing fluorescence only slightly above background signal for the three other proteins (Figure 3B). Four depletion sorts were performed per round, consisting of two sorts to bare streptavidin coated beads and two sorts to non-target protein coated beads. This sorting process enabled only Gp2 binders to the protein of interest to be carried through the affinity maturation process.

Soluble Protein Characterization

To examine if untethered Gp2 will retain its useful properties, the protein was produced and tested for binding and stability. Wild-type Gp2 could not be produced at detectable levels in a typical production E. coli strain, likely due to the protein’s native RNA polymerase inhibition function (Nechaev and Severinov, 1999). However, mutated clones were able to be produced, presumably due to mutation of many of the residues on Gp2 normally required to interact with DNA during transcription inhibition (Cámara et al., 2010). Protein titer, with no optimization, varied between 0.2 mg/L and 2.2 mg/L for different Gp2 mutants. The JE1 E. coli strain has the β-jaw portion of the E. coli RNA polymerase protein deleted (Ederth et al., 2002) and enabled production of Gp2 wild-type at 0.7 mg/L. All Gp2 molecules were verified by mass spectrometry to within 0.1% of the expected mass.

Structure and stability after mutation are important qualities of a potential protein scaffold. In order to evaluate secondary structure changes after Gp2 was evolved for new binding function, circular dichroism measurements were taken of the top binder for each target. The ellipticity spectra of the binding Gp2 proteins deviate only slightly from the wild-type Gp2, suggesting that the secondary structure remains relatively unchanged after multiple mutations in the backbone and entirely new loop regions (Figure 4A). The midpoint of thermal denaturation of each protein was measured by monitoring the loss of secondary structure at 218 nm as temperature increased (Table 1 and Figure 4B). Interestingly, the average stability of Gp2 binding mutants increased by 5 °C over Gp2 wild-type, which had a Tm = 67 ±1 °C. Gp2 mutants that were raised to 98 °C and brought down to room temperature had similar CD spectra as the initial measurements (Figure 4A). GαGIgG2.2.1 (containing a framework mutation, R44E, to increase production) maintained binding activity (Figure 4D) after reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography and heating to 98 °C, illustrating the chemical and thermal stability of the protein.

Figure 4. Soluble Gp2 characterization.

(A,B) Purified Gp2 clones (blue: wild-type, red: GαGIgG2.2.1, green: GαRIgG3.2.3) were analyzed by circular dichroism spectroscopy. (A) Molar ellipticity (θ) was measured at indicated wavelengths before (solid lines) and after (dashed lines) thermal denaturation. (B) Molar ellipticity was monitored at 218 nm upon heating from 25 °C to 98 °C at 1 °C per minute. (C) Biotinylated IgG (2 nM goat or 4 nM rabbit as appropriate) was incubated with the indicated concentration of purified Gp2 and used to label yeast displaying the corresponding Gp2 clone. IgG binding was measured by streptavidin-fluorophore via flow cytometry. (D) Purified GαGIgG2.2.1 was subjected to various treatments prior to use in the competitive binding assay (as in (C)). Unblocked is a control without Gp2 competition. Pre-HPLC uses competition by GαGIgG2.2.1 that was purified on a metal affinity column. Post-HPLC uses competition by GαGIgG2.2.1 purified by metal affinity chromatography and reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography and lyophilization. Post-heat uses competition by GαGIgG2.2.1 purified as in Post-HPLC along with heating to 98 °C and cooling back to 22 °C. Error bars are ±SD on n = 2 samples. See Figure S2 for GαLysA0.3.3.

The binding affinities of select soluble Gp2 clones, measured by equilibrium competition titration, were 0.4 ±0.3 nM for GαGIgG2.2.1 and 1.0 ±0.5 nM for GαRIgG3.2.3 (Table 1 and Figure 4C), showing good agreement with the KD’s obtained from yeast surface display affinity titration.

EGFR-Targeting Gp2 Domains

The success and ease of ligand discovery for the three model targets from the current Gp2 library motivated the search for a Gp2 ligand that strongly and specifically bound EGFR for use in cancer imaging or treatment. Through similar methods as the model targets, Gp2 ligand discovery was performed using soluble biotinlyated EGFR ectodomain as the target. After the second round of affinity maturation, strong binding was evident by flow cytometry with 50 nM soluble EGFR (Figure 5A). Deep sequencing indicated that GαEGFR2.2.3 was the dominant clone in the library and revealed several other families of sequences that were enriched during evolution. Purified Gp2-EGFR2.2.3 binds to intact membrane-bound EGFR with an affinity of 18 ±8 nM as measured by labeling A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells (Figure 5B) that highly overexpress EGFR on their surface (Hackel et al., 2012; Spangler et al., 2010). Gp2-EGFR2.2.3 exhibits secondary structure consistent with the wild-type Gp2 domain (Figure 4C) and is thermally stable (Tm = 71 ±2 °C, Figure 5C). Fluorescence microscopy was used to evaluate binding specificity. GαEGFR2.2.3, but not wild-type Gp2, effectively labels the cell surface of EGFRhigh A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells but not EGFRlow MCF7 mammary carcinoma cells (Figure 5D). Moreover, binding of biotinylated GαEGFR2.2.3 was blockable by excess unlabeled Gp2 (Figure 5E). Gp2 biotinylation was straightforward (with N-hydroxy succinimide biotin) due to the lone lysine residue at the N-terminus. To further validate that the evolved Gp2 domain can differentiate between different EGFR levels, four cell lines, A431 epidermoid carcinoma (EGFRhigh), MDA-MB-231 mammary carcinoma (EGFRmid), DU145 prostate carcinoma (EGFRmid), and MCF7 mammary carcinoma (EGFRlow) were labeled with GαEGFR2.2.3 and a secondary fluorophore. Fluorescence signal correlated with cell surface expression level of EGFR (Figure 5F).

Figure 5. GαEGFR2.2.3 affinity and stability.

(A) Population of yeast displaying Gp2 incubated with 50 nM EGFR and anti-c-myc antibody. Secondary fluorophores detect binding of EGFR and antibody. Spread of double positive cells suggests moderate diversity of EGFR binding Gp2 molecules. GαEGFR2.2.3 was collected from top 1% of double positives. (B) A431 cells were incubated with indicated amount of purified Gp2. Binding was detected by anti-His6 fluorophore. Titration indicates an equilibrium dissociation constant of 18 ±8 nM. (C) Molar ellipticity was monitored at 218 nm upon heating from 25 °C to 98 °C at 1 °C per minute. Molar ellipticity before (solid) and after (dashed) thermal denaturation is inset. (D) Fluorescence microscopy of adhered cancer cell lines, incubated with 100 nM Gp2 protein and detected by anti-His6-fluorescein. A431 cells labeled with GαEGFR2.2.3 (left column) show localization to cell surface. A431 cells labeled with Gp2 WT (middle column) and MCF7 cells labeled with GαEGFR2.2.3 (lower column) show very little detectable binding. Scale bar represents 200 µm. (E) A431 cells preincubated with PBS or 1 µM GαEGFR2.2.3 and labeled with 200 nM biotinylated GαEGFR2.2.3. Binding detected with streptavidin fluorophore. (F) Cancer cell lines expressing varying levels of EGFR: MCF7 with 2 × 104 receptors (gray line) (Reilly et al., 2000), MDA-MB-231 with 1 × 105 receptors (red dot) (Reilly et al., 2000), DU145 with 2 × 105 receptors (black dash) (Malmberg et al., 2011), and A431with 3 × 106 (green dash) (Spangler et al., 2010) were incubated with 1 µM GαEGFR2.2.3 and detected with anti-His6-fluorescein by flow cytometry.

Deep Sequencing of Naïve and Binding Populations

Deep sequencing was performed on the original library and the first enriched population in each target campaign that displayed significant selective binding represented by a 10:1 ratio of cells on target beads to control beads. Multiple binding sequence families were identified for each target (4,209 unique sequences in 153 families identified by 85% sequence identity). Sitewise changes in amino acid frequencies, relative to the original library, for heavily diversified loops (Figure 6A) and framework sites subject to error-prone PCR (Figure 6B) reveal site-specific amino acid preferences. Additionally, loop length frequency shows a slight change from the initial library to the evolved binders (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Deep sequencing comparison of naïve and binding populations.

All sequences were grouped into families and damped. (A) Diversified loop positions (CDR`) are shown at the top, with 9a and 9b, or 36a and 36b, representing loop length diversity positions. Positions with an absolute change of 5% or greater are labeled. All labeled positions have p < 0.001 (n ≥ 96, number of damped sequences). (B) Relative change in amino acid frequency by framework position from the naïve library to combined mature populations. Certain mutations are more common than others due to error prone PCR limitations. Positions where wild type was conserved (#) or mutated (*) significantly more often (p < 0.001 for 3% deviation, n ≥ 421) than the mean mutation rate are denoted. (C) Frequency of Gp2 loop length in amino acids. The naïve library was designed with equal loop length frequencies, but DNA bias during construction lead to overrepresentation of shorter loops. Mature combines high throughput sequencing from the four binding populations. All have p < 0.001. Error bars are ±SD for n = 4.9 × 104 for naïve and n ≥ 477 for mature (number of damped sequences). See also Figure S1.

Discussion

We sought to identify a protein scaffold with a unique combination of small size and robust evolvability of specific, high affinity binding while retaining stability. And we sought to evaluate the ability to identify such a scaffold via systematic analysis of protein topology and an estimation of mutational tolerance. Gp2 provides very small size (5 kDa, 45 amino acids) and has been efficiently evolved, to four different targets, to picomolar to nanomolar affinities with good specificity including strong discrimination between related IgGs. Evolved molecules exhibit good thermal and chemical stability (Tm = 65 – 80 °C with reversible unfolding and tolerance to reverse phase chromatography) and are functional in cellular assays. Gp2 succeeded with the combination of an effective topology, diversification design (tolerant loops of sufficient size, antibody-inspired amino acid bias, and shape diversity via loop length variation), and evolution method.

The particular topology of an α-helix opposite a three-strand β-sheet underpinning two diversified loops is a new structure for a generalized binding scaffold. Of course, loops have been successful with numerous other topologies including – as examples rather than an all-inclusive list – antibodies, fibronectin domains, and green fluorescent protein (Pavoor et al., 2009). Yet not all loop-presenting frameworks are equally efficacious as evidenced by varying performance of different scaffolds (Binz et al., 2005). Of note here, the second candidate in our theoretical scaffold evaluation – an SH3 domain from CD2 associated protein (Roldan et al., 2011) – has substantially different framework topology and loop orientation (Figure 1). This SH3 domain is a homolog (RMSD = 1.4 Å and TM-score = 0.79, where greater than 0.5 indicates similar fold (Zhang and Skolnick, 2005)) of the Fynomer scaffold, which has been evolved for low nanomolar affinity to five targets (Table S1) (Grabulovski et al., 2007; Panni et al., 2002). While the scaffold evaluation algorithm provides a framework for comparison, comparative experimental evaluation of numerous scaffolds is beyond the scope of the current study. Importantly, the demonstrated efficacy of Gp2 provides evidence of an improved ability to merge design goals in evolutionary capacity, affinity, and stability if the topology is properly selected.

Regarding evolutionary library design, while the diversified loops provided sufficient diversity for high affinity binding, adjacent framework mutations in several clones were noted (Table 1). Deep sequencing suggests that added diversity at the N-terminal edge of the second loop could be beneficial as E30, W31, and Q32 exhibited higher than average variance in binders relative to the naïve library (p < 0.001), presumably resulting from error-prone PCR during evolution (Figure 6B). In addition, K1 also exhibits an increased mutation rate (p=0.006), perhaps to account for change in exposure or structure due to the removal of the N-terminal tail. Conversely, lower than average mutation rates of sites F2, A4, P16, A25, Y33, and V40 (p < 0.001) suggest an evolutionary benefit to conservation at those sites. Notably, Y33 and V40 directly flank the diversified region of the second loop and are relatively buried in the protein core (19% and 21% solvent accessibility, respectively), suggesting a loop-anchoring benefit. Overall, mutation tolerance correlated with solvent accessibility (p=0.001, Figure S1). Antibody-inspired amino acid distribution was effective as it was closely maintained in binding sequences (Figure 6A) although evolutionary efficiency would benefit from slightly increased glycine, especially at select sites: amino acids 9–11 in the middle of the first loop and 34–35 at the start of the second loop. Meanwhile, evolutionary preference was evident for hydrophilic residues at sites 10 and 36 and hydrophobic residues at sites 12, 37, and 38. Loop length diversity was effectively utilized in binding sequences with a slight trend towards a longer first loop (18% decrease of wild-type 6-amino acid length and 33% increase of 8 amino acid loop; p < 0.001) and a second loop of wild-type length (12% increase; p < 0.001) (Figure 6C). Collectively, the diversification design was effective yet represents an avenue for improvement. While the Gp2 scaffold was robust in efficiently identifying effective binding molecules for each of the four disparate targets, one possible limitation is the modest number of lead molecules for each target. As scaffold size is reduced, the need to simultaneously optimize inter- and intra-molecular interactions is heightened, and the solution space is diminished. While all evolved clones exhibited appropriate secondary structure, good thermal stability, and effective binding, the frequency of mutational tolerance of the naïve library could be different. In fact, evolved proteins were readily produced in E. coli, albeit at moderate yields, and eight randomly selected initial library mutants were unable to be recovered in detectable amounts (data not shown), suggesting lack of solubility or stability in some naïve mutants. Refining the combinatorial library using sitewise optimization of diversity based on the aforementioned data could improve the breadth of solutions.

Effective lead ligands, such as GαEGFR2.2.3, which binds cellular EGFR with 18 ±8 nM affinity and has high thermal stability (71 °C), were identified. GαEGFR2.2.3 was effective in cellular labeling for immunofluorescence, flow cytometry, and binding inhibition. Notably, GαEGFR2.2.3 contains a single lysine at the N-terminus, distal to the proposed binding paratope, for conjugation of imaging moieties or molecules of therapeutic interest. The conjugation of biotin to the molecule without strong inhibition of binding suggests that other molecules can similarly be conjugated. Similar small proteins have shown advantages over antibodies in molecular imaging of solid tumors (Natarajan et al., 2013; Orlova et al., 2009), where enhanced transport and clearance afforded by small size are particularly valuable, and have exhibited clinical potential (Baum et al., 2010). It should be noted that, as with any synthetically engineered protein with non-human sequence components, immunogenicity of evolved molecules will need to be evaluated. Overall, Gp2 molecules represent a promising alternative with a unique blend of small size and robust evolution of stable, high affinity binders.

Significance

A systematic evaluation of the Protein Data Bank based on size, protein secondary structure, paratope structure, and resilience to mutation lead to further investigation of the small Gp2 domain. The ability to discover and evolve novel binding function on mutated Gp2 molecules is generalizable, with four targets currently tested. The small size, retention of thermal stability, and ease of evolving high affinity binding provide a unique and powerful combination in an alternative scaffold. The Gp2 molecules reported here that bind strongly and specifically to rabbit IgG, goat IgG, lysozyme, and EGFR have use immediately in biotechnology or, in the case of GαEGFR2.2.3, as a potential clinical imaging agent due to their single distal lysine available for conjugation of small molecules or other moieties. Moreover, deep sequencing of the binding populations provided insights on Gp2 evolution including mutational tolerance at non-loop positions and amino acid preference at individual loop positions. Overall, the initial successes of Gp2 combined with knowledge gained from sequence analysis suggest a promising scaffold that can be used to discover small, stable binders to many targets while providing an opportunity for ongoing study of evolutionary optimization of inter- and intra-molecular interactions in a small scaffold.

Experimental Procedures

Detailed experimental procedures are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Protein Data Bank Analysis

All single domains within the Protein Data Bank (accessed November 2011) were filtered to identify those with a size of 40–65 amino acids and at least 30% β-sheet. Note that several proteins outside of these bounds were nevertheless returned by the website’s filter. PyMol (Schrödinger, New York, NY) was used to visualize the structures of the 259 remaining proteins, and those that contained two or more adjacent solvent exposed loops whose surfaces formed one continuous face and had no disulfide bonds were further considered. The solvent accessible surface area of the loop residues was calculated, using a 1.4 Å sphere, after mutating residues to serines in Pymol (Fraczkiewicz and Braun, 1998). For the top 14 proteins, the destabilization upon random mutation of the loop residues was calculated using ERIS (Yin et al., 2007). Amino acid sequences were randomly generated using equal probability of each amino acid within the loops noted in Figure 1. Random mutants were analyzed until the mean destabilization converged within 0.25 kcal/mol for at least ten consecutive mutants (minimum 35 mutants total). This resulted in a maximum of 84 mutants with a median of 42 mutants.

Library Construction

A genetic library was constructed based on a truncated form of T7 phage gene 2 protein, the top scoring protein, in which the sequence encoding for two loops was randomized using degenerate oligonucleotides encoding for an amino acid distribution mimicking antibody CDRs (Hackel et al., 2010). At diversified positions (Figure 1) the mixtures of nucleotides were: 15% A and C, 25% G, and 45% T in the first position; 45% A, 15% C, 25% G, and 15% T in the second position; and 45 % C, 10% G, and 45% T in the third position. The DNA was transformed into yeast surface display system strain EBY100 via homologous recombination with a pCT vector (Chao et al., 2006). The total number of transformants was determined through serial dilution on SD-CAA plates (0.07 M sodium citrate (pH 5.3), yeast nitrogen base (6.7 g/L), casamino acids (5 g/L), and glucose (20 g/L)). Flow cytometry was used to determine the amount of full length Gp2 displayed, through labeling of the N-terminal HA epitope and C-terminal c-MYC epitope, and supported with DNA sequence verification. The design of the focused lysozyme library is described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Binder Selection and Affinity Maturation

Yeast displaying the Gp2 library were exposed to control magnetic beads (first avidin-coated beads then beads with immobilized non-target protein) to remove any non-specific binding interactions. Yeast were then exposed to magnetic beads with immobilized biotinylated target protein (goat IgG, rabbit IgG, lysozyme, or EGFR ectodomain) and bound yeast were selected. Magnetic sorts on the initial library were performed at 4 °C and only one wash. Non-naïve populations were sorted more stringently, at room temperature and with three washes. Flow cytometry selections, with biotinylated target protein and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated streptavidin, were used (Hackel and Wittrup, 2010) to isolate full length (c-MYC positive) Gp2 domain mutants that bind selectively and with high affinity toward the target proteins. Loop-focused and total gene error-prone PCR, using nucleotide analogs, and genetic loop shuffling between binding sequences were used to evolve improved function (Hackel et al., 2008).

Illumina MiSeq Analysis

Illumina MiSeq paired-end sequencing was conducted to obtain 4.9 × 104 reads from the naïve library and a total of 6.4 × 105 (CV = 24%) reads from binding populations. Loop one was analyzed independently from loop two. Mature loop one sequences were grouped into 95 families (>60% sequence similarity) with 249 unique sequences, and after damping (quad rooted) the adjusted sequence count was n ≥ 173 at each position. Mature loop two sequences were grouped into 96 families with 198 unique sequences, and after damping the adjusted sequence count was n ≥ 96 at each position. Sequences from the naïve library population were grouped into 4.9 × 104 families with 4.9 × 104 unique sequences, after damping the adjusted sequence count was ≥ 1.1 × 104 (due to fewer sequences at extended loop positions). Mature framework analysis grouped the sequences into 153 families (> 85% sequence similarity) with 4209 unique sequences, and after damping the adjusted sequence count was n ≥ 421 at each position. P values were calculated using a Welch’s t-test and assuming a normal distribution and using the number of damped sequences at each position as the sample size.

Affinity and Biophysical Properties

Binding affinities of evolved Gp2 molecules were determined by titrating target and evaluating binding using yeast surface display and flow cytometry (Chao et al., 2006). For GαLysA0.3.3 Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated streptavidin was mixed equimolar with singly biotinylated lysozyme at 2 µM prior to titration and yeast labeling. Gp2 domains were produced in E. coli, using strain JE1(DE3) for wild-type or BL21(DE3) for other Gp2 domains, purified by metal affinity chromatography and reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography, and verified by mass spectrometry. Purified Gp2 was suspended at 0.2 to 0.9 mg/mL in PBS (8.0 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/L KCl, 1.44 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.24 g/L KH2PO4, pH 7.2) or 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5.5, and secondary structure and thermal stability were evaluated by wavelength (200 to 260 nm) and temperature scans (25 to 98 °C at 218 nm) via circular dichroism spectroscopy. Binding affinity was further measured by equilibrium competition titration with purified Gp2, target protein, and Gp2 displayed on the yeast surface using flow cytometry (Lipovsek et al., 2007). For cellular EGFR affinity, A431 epidermoid carcinoma were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in humidified air with 5% CO2. Cells to be used in flow cytometry were detached using trypsin for a shorter time (3–5 min) than recommended. Detached cells were washed and labeled with Gp2-EGFR2.2.3 at varying concentrations for 15–30 min at 4 °C. Cells were pelleted and washed with PBSA (PBS + 0.1% w/v BSA), then labeled with fluorescein conjugated rabbit anti-His6 antibody for 15 min at 4 °C. For blocking, cells were also labeled with biotin-Gp2-EGFR2.2.3 and detected by Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated streptavidin. Fluorescence was analyzed on a C6 Accuri flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The equilibrium dissociation constant, KD, was identified by minimizing the sum of squared errors assuming a 1:1 binding interaction.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Systematic search of Protein Data Bank for small, evolvable protein binding scaffold

45 amino acid Gp2 has unique blend of small size, ease of evolution, and stability

De novo discovery of high affinity, specific Gp2 binders toward four targets

Gp2 evolved to target epidermal growth factor receptor

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Sivaramesh Wigneshweraraj for the JE1 E. coli strain and Aaron Becker at the University of Minnesota Genomics Center for assistance with Illumina sequencing. This work was partially funded by the Department of Defense (Grant W81XWH-13-1-0471 to B.J.H.), the National Institutes of Health (Grant EB019518 to B.J.H.), and the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackerman SE, Currier NV, Bergen JM, Cochran JR. Cystine-knot peptides: emerging tools for cancer imaging and therapy. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2014;11:561–572. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2014.932251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta S, Dooley K, Shur O. Replacing antibodies: engineering new binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2013;15:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071812-152412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum RP, Prasad V, Müller D, Schuchardt C, Orlova A, Wennborg A, Tolmachev V, Feldwisch J. Molecular imaging of HER2-expressing malignant tumors in breast cancer patients using synthetic 111In- or 68Ga-labeled affibody molecules. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51:892–897. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.073239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binz HK, Amstutz P, Plückthun A. Engineering novel binding proteins from nonimmunoglobulin domains. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1257–1268. doi: 10.1038/nbt1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JD, Labthavikul ST, Otey CR, Arnold FH. Protein stability promotes evolvability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:5869–5874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510098103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cámara B, Liu M, Reynolds J, Shadrin A, Liu B, Kwok K, Simpson P, Weinzierl R, Severinov K, Cota E, et al. T7 phage protein Gp2 inhibits the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by antagonizing stable DNA strand separation near the transcription start site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:2247–2252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907908107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel G, Chtéoui M, Heyd B, Tordo N. Phage display of combinatorial peptide libraries: Application to antiviral research. Molecules. 2011;16:3499–3518. doi: 10.3390/molecules16053499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao G, Lau WL, Hackel BJ, Sazinsky SL, Lippow SM, Wittrup KD. Isolating and engineering human antibodies using yeast surface display. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Sawyer N, Regan L. Protein-protein interactions: General trends in the relationship between binding affinity and interfacial buried surface area. Protein Sci. 2013;22:510–515. doi: 10.1002/pro.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran E, Hanson R. Imaging EGFR and HER2 by PET and SPECT: A Review. Med. Res. Rev. 2013;2:1–48. doi: 10.1002/med.21299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond R. Real-space refinement of the structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;82:371–391. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ederth J, Artsimovitch I, Isaksson La, Landick R. The downstream DNA jaw of bacterial RNA polymerase facilitates both transcriptional initiation and pausing. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:37456–37463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh RA, Bossemeyer D. Structural aspects of protein kinase control-role of conformational flexibility. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;93:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleetwood F, Klint S, Hanze M, Gunneriusson E, Frejd FY, Ståhl S, Löfblom J. Simultaneous targeting of two ligand-binding sites on VEGFR2 using biparatopic Affibody molecules results in dramatically improved affinity. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:7518. doi: 10.1038/srep07518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraczkiewicz R, Braun W. Exact and efficient analytical calculation of the accessible surface areas and their gradients for macromolecules. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19 [Google Scholar]

- Gai SA, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for protein engineering and characterization. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer M, Skerra A. Anticalins: Small Engineered Binding Proteins Based on th Lipocalin Scaffold. In Methods in Enzymology. 2012:157–188. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396962-0.00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gera N, Hussain M, Wright RC, Rao BM. Highly stable binding proteins derived from the hyperthermophilic Sso7d scaffold. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;409:601–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz JA, Rice JJ, Daugherty PS. Protease-resistant peptide ligands from a knottin scaffold library. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:837–844. doi: 10.1021/cb200039s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabulovski D, Kaspar M, Neri D. A novel, non-immunogenic Fyn SH3-derived binding protein with tumor vascular targeting properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3196–3204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel BJ. Alternative Protein Scaffolds for Molecular Imaging and Therapy. In: Cai W, editor. In Engineering in Translational Medicine. London: Springer London; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hackel BJ, Wittrup KD. The full amino acid repertoire is superior to serine/tyrosine for selection of high affinity immunoglobulin G binders from the fibronectin scaffold. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2010;23:211–219. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel B, Kimura R, Gambhir S. Use of 64Cu-labeled fibronectin domain with EGFR-overexpressing tumor xenograft: molecular imaging. Radiology. 2012;263:179–188. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel BJ, Kapila A, Wittrup KD. Picomolar affinity fibronectin domains engineered utilizing loop length diversity, recursive mutagenesis, and loop shuffling. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:1238–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel BJ, Ackerman ME, Howland SW, Wittrup KD. Stability and CDR composition biases enrich binder functionality landscapes. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;401:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LJ, Skaletsky E, McPherson A. Crystallographic structure of an intact IgG1 monoclonal antibody. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;275:861–872. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermeling S, Crommelin DJA, Schellekens H, Jiskoot W. Structure-immunogenicity relationships of therapeutic proteins. Pharm. Res. 2004;21:897–903. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000029275.41323.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes NE, MacDonald G. ErbB receptors and signaling pathways in cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide A, Bailey CW, Huang X, Koide S. The fibronectin type III domain as a scaffold for novel binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:1141–1151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent-Puig P, Cayre A, Manceau G, Buc E, Bachet J-B, Lecomte T, Rougier P, Lievre A, Landi B, Boige V, et al. Analysis of PTEN, BRAF, and EGFR status in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in wild-type KRAS metastatic colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:5924–5930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipovsek D. Adnectins: engineered target-binding protein therapeutics. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2011;24:3–9. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipovsek D, Lippow SM, Hackel BJ, Gregson MW, Cheng P, Kapila A, Wittrup KD. Evolution of an interloop disulfide bond in high-affinity antibody mimics based on fibronectin type III domain and selected by yeast surface display: molecular convergence with single-domain camelid and shark antibodies. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1024–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo ED, Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004;93:2645–2668. doi: 10.1002/jps.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfblom J, Feldwisch J, Tolmachev V, Carlsson J, Ståhl S, Frejd FY. Affibody molecules: engineered proteins for therapeutic, diagnostic and biotechnological applications. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2670–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg J, Tolmachev V, Orlova A. Imaging agents for in vivo molecular profiling of disseminated prostate cancer--targeting EGFR receptors in prostate cancer: comparison of cellular processing of [111In]-labeled affibody molecule Z(EGFR:2377) and cetuximab. Int. J. Oncol. 2011;38:1137–1143. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SJ, Leung CL, Cochran JR. Knottins: Disulfide-bonded therapeutic and diagnostic peptides. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2012;9 doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni M, Veronese S, Benvenuti S, Marrapese G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Gambacorta M, Siena S, Bardelli A. Gene copy number for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and clinical response to antiEGFR treatment in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Lancet. Oncol. 2005;6:279–286. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouratou B, Schaeffer F, Guilvout I, Tello-Manigne D, Pugsley AP, Alzari PM, Pecorari F. Remodeling a DNA-binding protein as a specific in vivo inhibitor of bacterial secretin PulD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:17983–17988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702963104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan A, Hackel BJ, Gambhir SS. A novel engineered anti-CD20 tracer enables early time PET imaging in a humanized transgenic mouse model of B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:6820–6829. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechaev S, Severinov K. Inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by bacteriophage T7 gene 2 protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:815–826. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlova A, Wållberg H, Stone-Elander S, Tolmachev V. On the selection of a tracer for PET imaging of HER2-expressing tumors: direct comparison of a 124I–labeled affibody molecule and trastuzumab in a murine xenograft model. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50:417–425. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panni S, Dente L, Cesareni G. In vitro evolution of recognition specificity mediated by SH3 domains reveals target recognition rules. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21666–21674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavoor TV, Cho YK, Shusta EV. Development of GFP-based biosensors possessing the binding properties of antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:11895–11900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902828106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly RM, Kiarash R, Sandhu J, Lee YW, Cameron RG, Hendler A, Vallis K, Gariépy J. A comparison of EGF and MAb 528 labeled with 111In for imaging human breast cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2000;41:903–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revets H, Baetselier P, De Muyldermans S. Nanobodies as novel agents for cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2005;5:111–124. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldan JLO, Blackledge M, van Nuland NAJ, Azuaga AI. Solution structure, dynamics and thermodynamics of the three SH3 domains of CD2AP. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;50:103–117. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg AS. Effects of protein aggregates: an immunologic perspective. AAPS J. 2006;8:E501–E507. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scartozzi M, Bearzi I, Mandolesi A, Pierantoni C, Loupakis F, Zaniboni A, Negri F, Quadri A, Zorzi F, Galizia E, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) gene copy number (GCN) correlates with clinical activity of irinotecan-cetuximab in K-RAS wild-type colorectal cancer: a fluorescence in situ (FISH) and chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) analysis. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MM, Wittrup KD. A modeling analysis of the effects of molecular size and binding affinity on tumor targeting. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2861–2871. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu SS. Antibodies for all: The case for genome-wide affinity reagents. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2778–2779. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler JB, Neil JR, Abramovitch S, Yarden Y, White FM, Lauffenburger Da, Wittrup KD. Combination antibody treatment down-regulates epidermal growth factor receptor by inhibiting endosomal recycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:13252–13257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913476107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern L, Case B, Hackel B. Alternative non-antibody protein scaffolds for molecular imaging of cancer. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2013;2:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaskovic R, Simon M, Stefan N, Schwill M, Plückthun A. Designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) from research to therapy. In Methods in Enzymology. 2012:101–134. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396962-0.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurber G, Schmidt M, Wittrup K. Antibody tumor penetration: transport opposed by systemic and antigen-mediated clearance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008a;60:1421. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurber GM, Schmidt MM, Wittrup KD. Factors determining antibody distribution in tumors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008b;29:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AM, Senter PD. Arming antibodies: prospects and challenges for immunoconjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1137–1146. doi: 10.1038/nbt1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S, Ding F, Dokholyan N. Eris: an automated estimator of protein stability. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:466–467. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0607-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnd C, Kawe M, Stumpp MT, de Pasquale C, Tamaskovic R, Nagy-Davidescu G, Dreier B, Schibli R, Binz HK, Waibel R, et al. Efficient tumor targeting with high-affinity designed ankyrin repeat proteins: effects of affinity and molecular size. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1595–1605. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Skolnick J. TM-align: A protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2302–2309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.