Abstract

Bax protein plays a key role in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release upon apoptosis. Our recent data have indicated that the 20-residue C-terminal peptide of Bax (BaxC-KK; VTIFVAGVL-TASLTIWKKMG), when expressed intracellularly, translocates to the mitochondria and exerts lethal effect on cancer cells. Moreover, the BaxC-KK peptide, as well as two mutants where the two lysines are replaced with glutamate (BaxC-EE) or leucine (BaxC-LL), have been shown to form relatively large pores in lipid membranes, composed of up to eight peptide molecules per pore. Here the pore structure is analyzed by polarized Fourier transform infrared, circular dichroism, and fluorescence experiments on the peptides reconstituted in phospholipid membranes. The peptides assume an α/β-type secondary structure within membranes. Both β-strands and α-helices are significantly (by 30–60 deg) tilted relative to the membrane normal. The tryptophan residue embeds into zwitterionic membranes at 8–9 Å from the membrane center. The membrane anionic charge causes a deeper insertion of tryptophan for BaxC-KK and BaxC-LL but not for BaxC-EE. Combined with the pore stoichiometry determined earlier, these structural constraints allow construction of a model of the pore where eight peptide molecules form an “α/β-ring” structure within the membrane. These results identify a strong membranotropic activity of Bax C-terminus and propose a new mechanism by which peptides can efficiently perforate cell membranes. Knowledge on the pore forming mechanism of the peptide may facilitate development of peptide-based therapies to kill cancer or other detrimental cells such as bacteria or fungi.

Bax is a member of B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family of proteins that play pivotal roles in apoptosis. Upon activation by apoptotic signals, Bax and other proteins such as Bak partition to mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, leakage of cytochrome c and caspase activators into the cytosol, followed by apoptotic cell death.1–3 The atomic-resolution NMR structure of Bax identified nine α-helices, two of which, helix 5 and helix 9, had increased hydrophobicity.4 On the basis of this structure and earlier notions of the importance of the C-terminus of Bax in mitochondrial localization during apoptosis,5,6 it was suggested that the C-terminal helix 9, which was located in a hydrophobic groove of the protein in solution, disengages and inserts into the mitochondrial membrane, probably together with helices 5 and 6, resulting in membrane pore formation and leakage of pro-apoptotic proteins.7 Deletions of C-terminal 21, 10, or even 5 amino acids inhibited mitochondrial localization capability of Bax upon induction of apoptosis,6–8 and various point mutations within the C-terminal helix 9 resulted in strong up- or down-regulation of its membranotropic activity,6 thus providing evidence for the key role of the C-terminus of Bax in its interaction with the mitochondrial membrane.

Peptides corresponding to Bax helices 5 and 6 were demonstrated to not only form efficient membrane pores that transport calcein and fluorescein-conjugated dextran molecules9,10 but also permeabilize mitochondria, release cytochrome c and cause apoptotic death of cancer cells.11 Bax C-terminal peptide has also been shown to permeabilize lipid membranes and cause leakage of carboxyfluorescein from vesicles.12,13 Deletion of Ser184, which results in constitutive mitochondrial localization of Bax,6 did not affect pore forming activity of the peptide, while replacement of Ser184 with lysine, which prevents its mitochondrial translocation during apoptosis,6 impaired the pore forming capability of the peptide.12,13 The structures of the peptides containing 21 or 24 C-terminal amino acid residues of Bax in aqueous and lipid environments were probed by circular dichroism (CD) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. A substantial fraction (40–44%) of intermolecular β-sheet structure was identified in the peptides in D2O buffer or in phosphatidylcholine membranes, evidenced by FTIR amide I components at 1626–1622 cm−1, along with ∼30% α-helical component at ∼1655 cm−1.13,14 The presence of anionic lipids such as phosphatidylglycerol or phosphatidylinositol in membranes resulted in an increase in α-helix and decrease in β-sheet conformations and promoted a transmembrane orientation of the peptide.14 Consistent with this, 31P- and 13C NMR spectra of liposomes in the presence and absence of the peptide suggested that phosphatidylglycerol promoted formation of a predominantly α-helical structure with a transmembrane orientation.15

These data provide strong support to the notion that Bax C-terminus is involved in mitochondrial membrane pore formation. However, the nature and the molecular details of the pore remain obscure. During membrane pore formation, Bax C-terminus is believed to be α-helical, oriented nearly perpendicular to the membrane plane, stabilized by electrostatic interactions between the two lysines and anionic lipid headgroups.14,15 Moreover, dominant α-helical structure and transmembrane insertion are thought to occur only in the case of anionic membranes.14,15 If membrane pores are formed only in anionic membranes by α-helical segments, then efficient carboxyfluorescein release from vesicles made of pure phosphatidylcholine,12 where the peptide assumes predominantly β-sheet structure,13,14 remains to be explained. Despite some inconsistencies, the existing data suggest that the isolated peptide has an intrinsic membrane pore forming potency and probably performs this function by a different mechanism as compared to the full length Bax protein.

Membrane perforation properties of peptides can be used to develop cytotoxic agents directed against bacteria, fungi, or transformed mammalian cells.11,16 Our recent studies have indeed demonstrated that the C-terminal 20-residue peptide of Bax efficiently kills breast and colon cancer cells when delivered using polymeric nanoparticles.17 The cytotoxic effect of the peptide was accompanied with mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization and plasma membrane rupture. Moreover, intratumoral or systemic injection of the nanoparticle-encapsulated peptide resulted in significant tumor regression in mice.17 Charge reversal or neutralization mutations of the two lysines significantly affected the cytotoxic potency of the peptide. To reach a better understanding of the pore forming potency of the peptide at a molecular level, we have undertaken a biophysical analysis of pore formation by the peptide. We have recently demonstrated that the Bax C-terminal peptide and two mutants where the two lysines were replaced with glutamate or leucine efficiently permeabilize zwitterionic and anionic phospholipid membranes, and have evaluated the oligomeric state of membrane pores.18 Here we present structural studies that lead to a molecular model of the transmembrane pore formed by Bax C-terminus. In the presence of bulk water, the peptides assume a α/β-type structure, with the β-strands and α-helices significantly tilted relative to the membrane normal. The tryptophan residue is located close to the membrane–water interface for zwitterionic membranes and inserts more deeply into anionic membranes in cases of BaxC-KK and BaxC-LL peptides. Altogether, the data are consistent with an octameric “α/β-ring” structure with an internal pore diameter large enough to effectively transfer calcein and larger molecules. Our results establish a foundation for characterization of the molecular structure of the transmembrane pore formed by Bax-derived peptides and will be used in further studies to develop peptide-based cytotoxic agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The peptides, i.e., BaxC-KK (Ac-VTIFVAGVL-TASLTIWKKMG-NH2), BaxC-EE, and BaxC-LL were synthesized by Biopeptide Co., Inc. (San Diego, CA) and were >98% pure as shown by HPLC and mass-spectrometry. BaxC-KK peptide 13C-labeled at main chain carbonyl carbons of Phe4 or both Phe4 and Lys17 were synthesized by EZBiolab (Carmel, IN) using the labeled amino acids provided by Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All lipids, i.e., 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (POPG), dodecylphosphocholine (DPC), and 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl-dibromo-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholines (Br2PC) brominated at 6,7-, 9,10-, or 11,12-positions of the sn-2 acyl chain were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). SM-2 Bio-beads were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were of the highest purity available. Polycarbonate filters for lipid vesicle preparation were purchased from Avestin, Inc. (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Germanium plates for infrared experiments were from Spectral Systems (Irvington, NY).

Peptide Reconstitution in Lipid Vesicles

To prepare large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs), chloroform or chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) solutions of lipids were mixed at desired proportions, solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen followed by desiccation for 3 h, an aqueous buffer was added and the lipid was suspended by vortexing, and the suspension was extruded through 200 nm pore-size polycarbonate filters using a LiposoFast extruder (Avestin, Inc.). The lyophilized peptides were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 0.3 mM and stored at −80 °C as stock solutions. For membrane insertion experiments, DMSO was removed under a stream of nitrogen and the sample was vacuum-desiccated for 3 h. Hexafluoroisopropanol was added to dissolve the peptide, and DPC dissolved in chloroform was added to reach a peptide-to-DPC molar ratio of 1:60, at DPC concentration of 9.0 mM. Following gentle mixing, the solvent was removed as described above and the peptide-DPC sample was suspended in 30 μL of 20 mM Na,K-phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. The peptide solubilized in DPC micelles was added to 270 μL of preformed LUVs, resulting in a 10-fold dilution of the peptide and DPC. Dispersion of DPC upon dilution below its critical micelle concentration (∼1.5 mM) resulted in incorporation of the hydrophobic peptide into LUVs. Monodisperse DPC was removed from the sample by adding SM-2 Bio-beads (∼10% by weight), vortexing for 2 h and removing the Bio-beads. The final lipid and peptide concentrations were 1.0 mM and 15 μM, respectively.

Membrane Insertion of Peptides

Membrane insertion depth of the peptides was evaluated as previously described.19,20 Each peptide was reconstituted in membranes composed of 90% POPC and 10% Br2PC or 60% POPC, 30% POPG, and 10% Br2PC, as described above, in a buffer of 20 mM Na,K-phosphate and 0.8 mM EGTA (pH 7.2). For both zwitterionic (without POPG) and anionic (with 30% POPG) membranes, three different Br2PCs were used that were brominated at 6,7-, 9,10-, or 11,12-positions of their sn-2 acyl chains. In control experiments, the vesicles were prepared without Br2PC. Following peptide reconstitution into the vesicles, the sample was placed in a 4 × 4 mm2 rectangular quartz cuvette and tryptophan fluorescence spectra were measured on a J-810 spectrofluoropolarimeter (Jasco, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) using excitation at 290 nm, with constant stirring with a magnetic stir bar. The excitation and emission bandwidths were 3 and 10 nm, respectively. Measurements were conducted at 20 and 37 °C, using a PFD-425S Peltier temperature controller, and 5 spectra were coadded to obtain an average fluorescence emission spectrum between 300 and 400 nm. Fluorescence spectra without and with the three Br2PC quenchers were used to determine the quenching efficiency of each brominated lipid, i.e., ln(F0/F), where F0 and F are fluorescence intensities at 340 nm in the absence and presence of the quencher, and values of ln(F0/F) were plotted vs. the distance of bromines from membrane center, i.e., h = 11.0 Å, 8.3 Å, and 6.5 Å for Br2PCs brominated at 6,7-, 9,10-, and 11,12-positions of the sn-2 acyl chain.21 These plots were fitted with a Gaussian distribution curve:

| (1) |

where S is the area under the curve and is proportional to the extent of exposure of the fluorophore to the membrane hydrophobic interior, σ is the dispersion (half-width at half-height) of the distribution curve, and hm indicates the average (most probable) location of the fluorophore relative to the membrane center.

Circular Dichroism Measurements

CD spectra of DPC-solubilized or membrane-reconstituted peptides were measured using a J-810 spectrofluoropolarimeter. The sample was placed in a 4 × 4 mm2 rectangular quartz cuvette containing a magnetic stir bar and mounted in the temperature-controlled sample holder. DPC-solubilization was achieved as described above, at final DPC and peptide concentrations of 4 mM and 35 μM, respectively. Given DPC aggregation number of ∼60,22 this molar ratio corresponds to less than one peptide molecule per micelle and hence ensures the homogeneity of the sample, where each micelle contains no more than one peptide molecule. LUVs were prepared as described above, using pure POPC or a 7:3 molar combination of POPC/POPG, without Br2PC, and 10 scans were measured per spectrum between 190 and 310 nm. Measurements were conducted at both 20 and 37 °C.

Solid State NMR Experiments

Peptide-lipid samples for solid state NMR experiments were prepared as described elsewhere.23 Briefly, 2 mg of BaxC-KK, 13C-labeled at carbonyl carbons of Phe4 or both Phe4 and Lys17, were dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol and mixed with POPC/POPG (7:3) in chloroform, at a peptide to lipid molar ratio of 1:20. The solvent was evaporated by desiccation, and the dry sample was suspended in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), freeze–thawed 10 times, extruded through 200 nm pore-size polycarbonate membranes, and ultracentrifuged at 200000g for 1 h at 4 °C. About 0.5 μmol of peptide was packed into NMR rotors for each sample. NMR data were acquired at 100.39458 MHz 13C NMR frequency (9.38 T) at 9 kHz magic angle spinning using a 3.2 mm triple-resonance Balun magical angle spinning probe (Varian), at the Laboratory of Chemical Physics, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Cooling gas at −144 °C was passed to the sample space via the variable-temperature stack during experiments to maintain the sample at ∼15 °C, as determined by the 1H NMR frequency of water in samples.24

1D 13C spectra were acquired with two-pulse phase-modulated (TPPM) 1H decoupling at 105 kHz of 25.6 ms (1024 points, 25 μs dwell time) and recycle delay of 1 s. The 13C and 1H RF fields during 1.5 ms cross-polarization (CP) was at 60 and 69 kHz, respectively. The same CP condition and recycle delay were employed for 2D 13C–13C correlation spectra. Radio-frequency-assisted spin diffusion (200 and 500 ms) was utilized to establish 2D correlation.25 TPPM decoupling at 105 kHz was applied to both t1 period (128 points with 26.76 μs increment) and t2 period (512 points with 26.76 μs dwell), and continuous wave decoupling of 105 kHz was used for the rest of the pulse sequence. All NMR data were processed with NMRpipe26 and plotted with Sparky (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky/). The chemical shift was referred to tetramethylsilane.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Lipid-peptide samples for attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) experiments were prepared using a previously described method27 with slight modifications. Two microliters of the peptide sample dissolved in DMSO at 12.5 mM was dried under a stream of nitrogen and by desiccation. The dry peptide was dissolved in ∼20 μL of hexafluoroisopropanol, and 125 μL of 10 mM lipid dissolved in chloroform was added. The peptide-lipid solution at a lipid-to-peptide molar ratio of 50:1 was carefully spread onto a ∼7 cm2 surface area on one side of a clean germanium internal reflection element with 45° aperture angles and dimensions of 5.0 × 2.0 × 0.1 cm3. The sample was dried in a desiccator, the germanium plate was assembled in a homemade ATR sample holder, which was mounted into the FTIR spectrometer at a position corresponding to a 45° incidence angle. This setting corresponds to 20 internal reflections at one side of the plate. The thickness of the sample was estimated to be ∼1.6 μm, which is significantly thicker compared to the decay length of the evanescent wave (∼0.4 μm). After measurements of the spectra of the dry sample at parallel (II) and perpendicular (⊥) polarizations of the incident infrared light, the germanium plate with the sample was subjected to saturated D2O vapors for 1 h in a small, confined volume, was assembled in the ATR cell, and the spectra of the D2O-humidified sample were collected. This was followed by injection of a D2O-based buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, pH* 6.8) into the ATR cell and collection of additional spectra at both polarizations (pH* is the pH-meter reading and is 0.4 pH units lower compared to real pD, due to the isotope effect).28

FTIR spectra were collected using a Vector 22 infrared spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA), equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled Hg–Cd–Te detector and a software-operated aluminum grid on KRS-5 polarizer (Specac, Suffolk, UK), at 20 ± 1 °C. Each spectrum was the average of 500 scans, at 2 cm−1 nominal resolution. The spectrometer was continuously purged with dry air, additionally dried by passing through a silicagel column (Parker Balston, Haverhill, MA). The reference spectra were measured using a bare germanium plate or a sample prepared using plane lipid without any peptide. Atmospheric water humidity spectra were measured at II and ⊥ polarizations by collecting spectra at various times of purging with dry air, using the bare germanium plate, and were used for clearing the sample spectra from noise generated by residual humidity, when necessary.

FTIR Data Analysis

To evaluate the secondary structures of membrane-bound peptides, first ATR-FTIR spectra measured at parallel and perpendicular polarizations were used to generate a “polarization-independent” spectrum: A = AII + GA⊥, where the scaling factor G is given as29

| (2) |

Under our experimental conditions, the orthogonal components of the incident infrared radiation are Ex = 1.399, Ey = 1.514, and Ez = 1.621, and consequently G = 1.44. After obtaining a corrected amide I spectrum, the second derivative was calculated, which identified the number and the frequencies of amide I components. The curve-fitting of the amide I band was conducted using the GRAMS software. The result of curve-fitting was considered satisfactory when (i) the curvefit (the sum of all components) accurately reproduced the measured spectrum, and (ii) the deviations of the frequencies of amide I components from those predicted by second derivatives were less than the spectral resolution of the measurements, i.e., 2 cm−1. The fractions of secondary structures in the peptides were determined based on the amide I areas (ai) of components assigned to certain structures and respective extinction coefficients (ɛi):

| (3) |

where subscripts α, β, t, and ρ refer to α-helix, β-strand, turn, and irregular structure, respectively. For extinction coefficients of various structures of peptides exposed to a D2O-based buffer, the following values have been used: ɛα = 5.1 × 107 cm/mol, ɛβ = 7.0 × 107 cm/mol, ɛt = 5.5 × 107 cm/mol, and ɛρ = 4.5 × 107 cm/mol.30 Assignments of amide I components to certain secondary structures were done following standard and well established assignment procedures.31–33 Typically, components between 1657 and 1646 cm−1 were assigned to α-helix, those between 1637 and 1628 cm−1 to β-strand, those between 1627 and 1615 cm−1 to intermolecular β-sheet, those between 1645 and 1638 cm−1 to irregular structure, and those between 1700 and 1658 cm−1 to turns. The antiparallel β-sheet has an additional component around 1680–1670 cm−1, which is difficult to distinguish from turn components. The extinction coefficient of this higher frequency component is ∼7% of the lower frequency counterpart.30,31 Therefore, the total β-sheet fraction was determined by multiplying the fraction of the low frequency β-sheet component area (fβ,low) by 1.07. The fraction of turns then was corrected by subtracting 0.07 × fβ,low from the sum of the components between 1700 and 1658 cm−1.

Orientations of α-helical and β-sheet structures of the peptides and the lipid acyl chains were determined based on polarized ATR-FTIR spectra as follows. The molecular order parameter of the α-helical segment of the peptide was determined from polarized ATR-FTIR experiments as33

| (4) |

Here, , α is the angle between the transition dipole moment and the molecular axis (for an α-helix, α = 38–40°), R is the ATR dichroic ratio: R = aII/a⊥, where aII and a⊥ are the integrated absorbance intensities of helical amide I components at respective polarizations of the incident light, and angular brackets indicate average values.

Lipid hydrocarbon chain order parameter can be evaluated through eq 4 using an angle α = 90 °. The average angle θ between the membrane normal and the molecular axis, such as the helical axis or the lipid acyl chain long axis, can be found from the relationship:

| (5) |

Determination of the β-strand orientation is more complex, but becomes straightforward when the strands are arranged in a structure that is characterized by a central rotational axis.34 In this case,

| (6) |

where δ is the angle of the transition dipole moment of β-strands with respect to the central axis, and γ describes the orientation of central axis with respect to the membrane normal. For β-strands, the transition dipole moments of amide I and amide II modes are oriented perpendicular and along the strand axis, respectively.34 Therefore,

| (7a) |

and

| (7b) |

where subscripts I and II indicate amide I and amide II bands, respectively, and β is the angle between strand axes relative to the central axis. Substituting eqs 7a and 7b into eq 6 we obtain two equations that can be solved together, using the experimentally determined dichroic ratios for amide I and amide II bands, to evaluate the angles γ and β. However, this cannot be done in our case because (i) the peptides were shown to adopt α/β secondary structures and the amide II band cannot be easily divided into its α and β components, and (ii) the experiments were conducted using a D2O-based buffer that strongly affects the amide II band via deuteration of the backbone NH group. A reasonable approach has been used to overcome this obstacle. Equations 6 and 7a were combined to obtain an equation that contains two unknowns, β and γ. Parameter B was determined using the dichroic ratio R = aβII/aβ⊥, where aβII and aβ⊥ are the areas of amide I components assigned to β-strands at respective polarizations. Then the angle β was calculated using values of γ varying within a conceivable range, i.e. between 0 and 20 degrees. This yields quite meaningful results, especially considering that variation of γ within this range is related with only 3% to 13% changes in β (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Orientations of the Peptides in Membranes Derived from Polarized ATR-FTIR Experimentsa

| peptide/lipid | Rh | Sh | θh(°) | Rs |

β(°)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ = 0° | γ = 20° | |||||

| BaxC-KK/PC | 1.84 ± 0.09 | −0.120 ± 0.071 | 59.8 ± 3.1 | 1.71 ± 0.12 | 31.4 ± 1.8 | 30.6 ± 2.2 |

| BaxC-KK/PC:PG | 2.51 ± 0.13 | 0.318 ± 0.071 | 42.4 ± 5.4 | 2.39 ± 0.18 | 39.3 ± 1.6 | 40.1 ± 2.0 |

| BaxC-EE/PC | 1.95 ± 0.10 | −0.036 ± 0.074 | 56.2 ± 3.1 | 1.29 ± 0.09 | 23.6 ± 2.1 | 20.5 ± 2.9 |

| BaxC-EE/PC:PG | 2.09 ± 0.06 | 0.063 ± 0.041 | 52.2 ± 1.6 | 1.66 ± 0.14 | 30.7 ± 2.2 | 29.6 ± 2.8 |

| BaxC-LL/PC | 1.82 ± 0.07 | −0.136 ± 0.056 | 60.5 ± 2.5 | 1.45 ± 0.11 | 27.0 ± 2.2 | 25.0 ± 2.7 |

| BaxC-LL/PC:PG | 1.89 ± 0.05 | −0.082 ± 0.038 | 58.1 ± 1.6 | 1.75 ± 0.13 | 32.0 ± 1.9 | 31.3 ± 2.3 |

Rh and Rs are the dichroic ratios of helical or strand structures, respectively, θh is the average tilt angle of helices relative to the membrane normal, β is the tilt angle of strands relative to the pore axis, γ is the angle of pore axis relative to the membrane normal. Standard deviations are generated by three independent experiments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Secondary Structures of Membrane-Bound Peptides

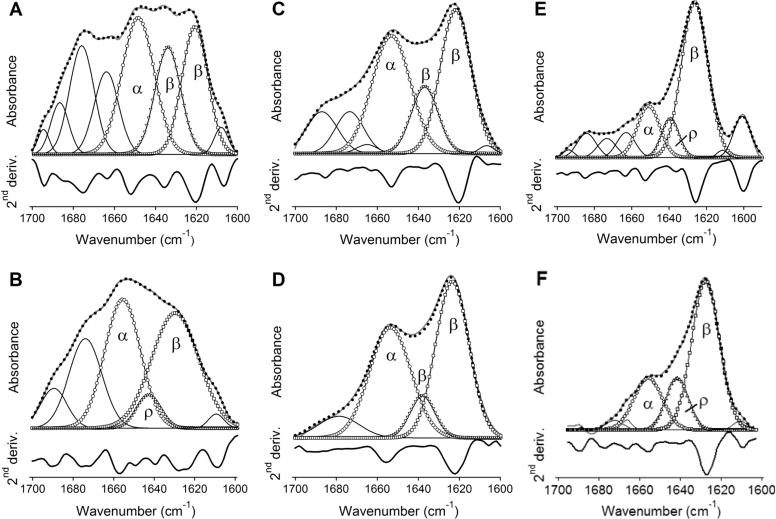

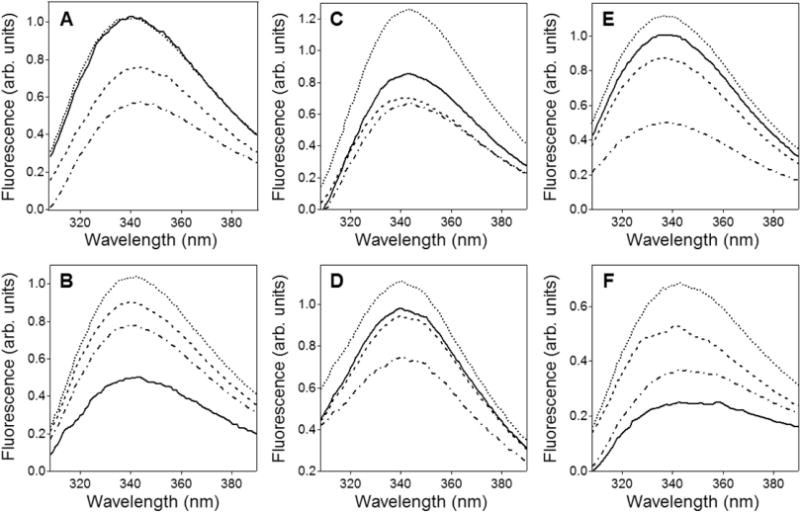

To determine the molecular structure of membrane pores formed by the peptides, we evaluated the secondary structure and orientation of membrane-bound peptides and the depth of membrane insertion. As a first step, polarized ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was used to determine the secondary structures of the peptides in lipid multilayers. The peptide-lipid system was deposited on a germanium plate, humidified by D2O vapor for 1 h, and eventually hydrated with a D2O-based buffer. Under each of these conditions, i.e., dry, humidified, and totally hydrated samples, ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded at II and ⊥ polarizations of the incident light. Because the relative absorbance intensities of different secondary structures of a molecule in an aligned sample depend on spatial orientations of respective structural elements, the secondary structure contents were determined using a hybrid spectrum, A = AII + 1.44A⊥ (see Materials and Methods). These “polarization-independent” spectra obtained in the presence of the aqueous buffer are shown in the amide I region in Figure 1. Clearly, these are composite, multicomponent spectra, indicating more than one secondary structure in each peptide. The second derivatives, shown under each spectrum, identify the locations and the relative intensities of the amide I components, and have been used to obtain the component peaks by curve-fitting. As judged from the line-shapes of the amide I spectra, the second derivatives, and the results of curve-fitting, all three peptides exhibit α-helical, β-sheet, and turn structures, in some cases also involving irregular structure. The wild-type BaxC-KK peptide clearly shows marked components at 1656–1650 cm−1 and 1638–1620 cm−1 in both POPC and POPC/POPG membranes (Figure 1A,B), which are readily assigned to α-helix and β-sheet structures, respectively.31–33 BaxC-EE and especially BaxC-LL peptides exhibit increased β-sheet and decreased of α-helical structures (Figure 1C–F). Since the C-terminal segment of Bax protein adopts an α-helical structure, as determined by solution NMR,4 the presence of significant β-sheet structure in the wild-type and mutant peptides is intriguing and indicates that either the behavior of the separated peptide differs from that within Bax protein or membrane binding promotes an α-helix-to-β-sheet conformational change. Two distinct components have been assigned to β-sheet structures, i.e., those between 1638 and 1634 cm−1 and those located at lower frequencies, between 1630 and 1620 cm−1. These amide I spectral regions typically are assigned to intramolecular and intermolecular (“aggregated”) β-sheets, respectively, although the amide I frequency of a β-sheet can vary within the 1640–1620 cm−1 range depending on hydrogen bonding strength and transition dipole coupling effects.31–33 The latter effect also generates higher frequency vibrations between 1700 and 1670 cm−1 for antiparallel β-sheets; separation of this component from overlapping turn structures is described in Materials and Methods.

Figure 1.

The wild-type and mutant peptides reconstituted in lipid membranes adopt an α/β-type secondary structure. ATR-FTIR spectra of BaxC-KK (A, B), BaxC-EE (C, D), and BaxC-LL (E, F) peptides in POPC (A, C, E) or POPC/POPG (7:3) (B, D, F) multilayers deposited on a germanium plate, under an aqueous buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes in D2O, pH* 6.8). The spectra generated by a linear combination of the original spectra measured at parallel and perpendicular polarizations of the incident infrared light, A = AII + 1.44A⊥, are shown in gray solid lines. The sums of all amide I components are shown in dotted lines. The amide I components corresponding to α-helix, irregular structure (ρ), intramolecular β-sheet, and intermolecular β-sheet are marked by circles, right triangles, inverted triangles, and squares, respectively. Amide I components above 1657 cm−1 shown in solid lines have been assigned to turns. Below each amide I spectrum, its second derivative is shown, in which the downward peaks indicate the locations of amide I components.

The amide I bands have also been analyzed for peptide-lipid systems in the absence of excess aqueous buffer, i.e., for dry and D2O-vapor-humidified samples. BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE peptides in dry samples contained significantly larger α-helical than β-sheet structure, while the dominant structure in BaxC-LL was β-sheet (Figure S1 of Supporting Information). In all cases, hydration of the sample with D2O vapor resulted in a decrease in α-helical structure and increase in β-sheet structure (Figure S1). This effect was further augmented upon hydration of the sample with a D2O-based buffer (Figure 1).

Formation of stable α-helical or β-sheet secondary structures by peptides in the absence of water, such as in vacuum, in gas phase, or in dry lipid systems, has been demonstrated.35–37 Although the presence of water destabilizes both α-helix and β-sheet structures via formation of H-bonding between the solvent and the peptide main chain carbonyls,36–38 a water-induced α-helix-to-β-sheet transition can occur due to a more effective protection of the peptide backbone from solvent by the peptide side chains in a β-sheet conformation.39 For example, melittin in dry lipid multilayers was in an α-helical conformation as evidenced by a dominant FTIR peak at 1656 cm−1 but adopted a β-sheet structure with a peak at 1635 cm−1 when associated with a lipid layer at an air–water interface.35,40 Earlier FTIR studies on Bax C-terminal peptide did demonstrate significant intermolecular β-sheet components at 1622–1626 cm−1,13,14 consistent with data of Figures 1 and S1.

Our data obtained on peptide–membrane systems under excess water are analyzed in more detail because of their physiological relevance. The fractions of α-helical, β-sheet, turn, and irregular structures and respective numbers of amino acid residues in membrane-reconstituted peptides are summarized in Table 1. BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE contain approximately equal numbers of residues (6–10 residues) in α-helix and β-sheet conformations, and BaxC-LL has a 2–3-fold larger fraction of β-sheet than α-helix. The peptides incorporate 2–5 residues in turn structure, which may be involved in transition between α-helix and β-sheet, except for BaxC-LL in POPC/POPG membranes, where the turn is replaced with irregular structure suggesting a linkage between the helix and strand structures through a short, 4–5-residue loop. Thus, ATR-FTIR data indicate a α/β type structure in all three peptides reconstituted in lipid multilayers. The content of β-sheet structure is close to or greater than that of α-helix, and the β-strands are most likely involved in intermolecular antiparallel sheets.

Table 1.

Secondary Structure of the Peptides in Membranes Derived from ATR-FTIR Experimentsa

| peptide/lipid | fh | Nh | fs | Ns | ft | Nt | Fρ | Nρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaxC-KK/PC | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 8.4 ± 1.0 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| BaxC-KK/PC:PG | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| BaxC-EE/PC | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| BaxC-EE/PC:PG | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 7.8 ± 0.8 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| BaxC-LL/PC | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 10.8 ± 0.8 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| BaxC-LL/PC:PG | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 10.6 ± 0.8 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

f is the fraction and N is the number of amino acid residues in α-helix (h), β-strand (s), turn (t) or irregular (ρ) structures. PC refers to 100% POPC membranes, and PC:PG to 70% POPC and 30% POPG membranes. Standard deviations are generated by three independent experiments.

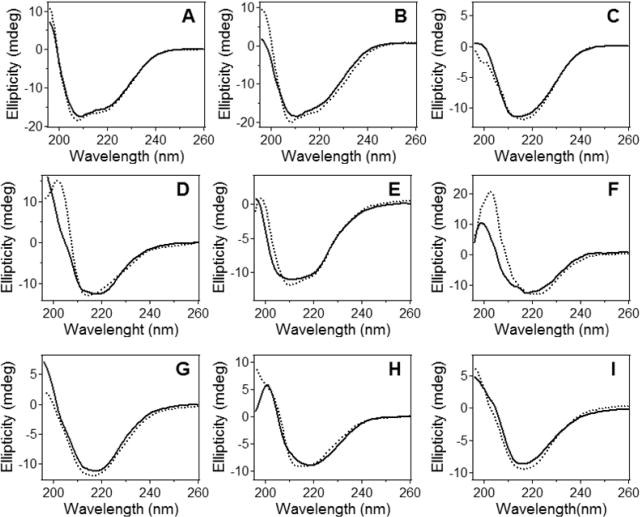

The secondary structures of DPC-solubilized and membrane-reconstituted peptides were evaluated by an independent method, i.e., CD spectroscopy. Far-UV CD spectra of BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE peptides in DPC micelles displayed a minimum around 208 nm and a shoulder at 216–222 nm (Figure 2A,B), which evidently result from overlapping α-helical ππ* and nπ* and β-strand nπ* transitions.41,42 The spectra of BaxC-LL in DPC showed a smooth minimum at 215–218 nm (Figure 2C), indicating a predominantly β-sheet structure. When reconstituted in POPC or POPC/POPG (7:3) vesicles, the spectra of all three peptides were dominated by a minimum between 216 and 220 nm, characteristic of β-sheet structure (Figure 2D–I). For water-soluble peptides, the β-sheet nπ* transition occurs around 216 nm, and the slight red shift observed for Bax peptides in lipid membranes (e.g., Figure 2F) may indicate a more nonpolar microenvironment of the peptides due to membrane insertion.41 We interpret the CD data in qualitative rather than quantitative terms because the limiting values of ellipticities for various secondary structures have not yet been firmly established. CD experiments have been carried out at both 20 and 37 °C because our earlier studies on pore forming activities of the peptides were conducted at 37 °C18 and the FTIR experiments described here were performed at 20 ± 1 °C; it was important to ensure that the peptides do not undergo significant structural changes within this temperature range and hence FTIR-derived structures can be used for construction of the pore model. Data of Figure 2 indicate little differences between 20 and 37 °C, consistent with the notion that proteins and peptides do not experience considerable conformational changes below 37 °C.43 Thus, CD data are consistent with a mixed β-sheet and α-helical structure of the peptides, as inferred from FTIR experiments. Moreover, CD spectra suggest an increased β-sheet propensity for BaxC-LL as compared with BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE peptides, which is consistent with FTIR data.

Figure 2.

The peptides in DPC micelles and lipid vesicles contain α-helical and β-sheet structures. Circular dichroism spectra of BaxC-KK (A, D, G), BaxC-EE (B, E, H), and BaxC-LL (C, F, I) peptides in DPC micelles (A, B, C), POPC unilamellar vesicle membranes (D, E, F) and POPC/POPG (7:3) unilamellar vesicle membranes (G, H, I) at 20 °C (dotted lines) and 37 °C (solid lines). Total concentrations of the lipid, DPC and the peptides were 1.0 mM, 4.0 mM, and 35 μM, respectively, in a buffer containing 20 mM Na,K-phosphate and 0.8 mM EGTA (pH 7.2).

Orientation of Membrane-Bound Peptides

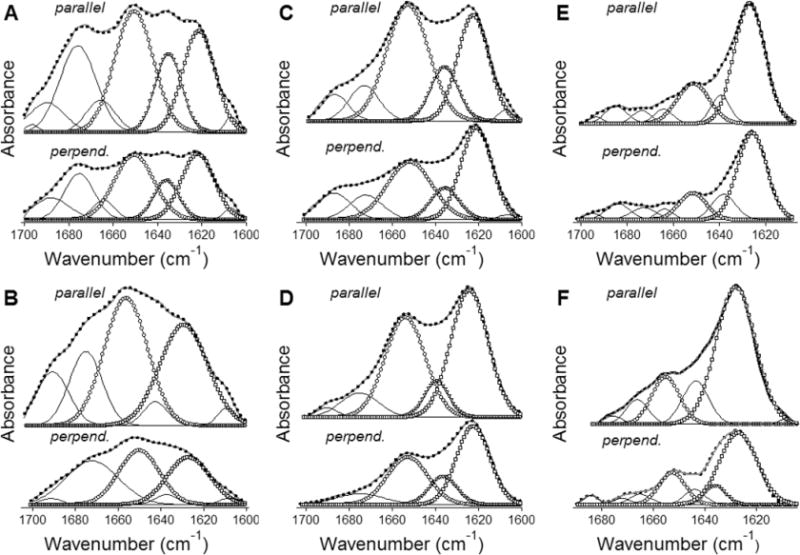

As a next step in structural characterization of membrane pores formed by Bax peptides, the orientations of the α-helical and β-strand segments of the peptides were evaluated by polarized ATR-FTIR experiments. Linear dichroic ratios for α-helices and β-strands, Rh and Rs, were determined as Rh = aαII/aα⊥ and Rs = aβII/aβ⊥, where aα and aβ are the areas of α-helical of β-sheet components of amide I bands measured at II or ⊥ polarizations, as indicated in Figure 3. Values of Rh were used to evaluate α-helical order parameters (Sh) and then the average tilt angles (θh) with respect to the membrane normal, using eqs 4 and 5. The helices in all three peptides appear to be at an oblique orientation, tilted from the membrane normal by 40–60 degrees (Table 2). The orientations of the β-strand segments were estimated assuming the strands were arranged in a structure characterized with a central rotational axis, like in a β-barrel. This is a reasonable conjecture given the fact that eight peptide molecules in predominantly β-sheet structure assemble to form a membrane pore.18 As described in Materials and Methods, values of Rs were used to determine the average angle of strand axis relative to the central axis of the pore. This procedure requires the orientation of the pore itself with respect to the membrane normal, i.e., the angle γ. The orientation of the β-strands relative to the pore axis (angle β) was determined for angles γ varying within a reasonable range, i.e., 0–20 degrees. Values of the angle β determined using this approach indicate strand tilt angles of 20–30 degrees for the peptides in POPC membranes and 30–40 degrees for the peptides in POPC/POPG membranes (Table 2). The latter is similar to the strand orientations in bacterial and mitochondrial β-barrel porin proteins.44–46 Variation of the pore orientation relative to the membrane normal between 0 and 20 degrees results only in a small uncertainty of 3–13% in values of the angle β. Thus, polarized ATR-FTIR data on the peptides in lipid multilayers in the presence of excess aqueous buffer indicate that both α-helical and β-strand structures in the peptides are tilted from the membrane normal (or from the pore axis if the pore central axis is collinear to the membrane normal) by 40–60 degrees and 20–40 degrees, respectively. In the case of the wild-type BaxC-KK peptide in POPC/POPG membranes, which is the most biologically relevant situation, both helices and strands are oriented at approximately 40 degrees from the membrane normal (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Polarized ATR-FTIR spectroscopy indicates that both α-helices and β-strands are tilted relative to the membrane normal. Polarized ATR-FTIR spectra of BaxC-KK (A, B), BaxC-EE (C, D), and BaxC-LL (E, F) peptides in POPC (A, C, E) or POPC/POPG (7:3) (B, D, F) multilayers deposited on a germanium plate, under an aqueous buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes in D2O, pH* 6.8). In each panel, spectra measured at parallel and perpendicular polarizations of the infrared light are shown, as indicated. The experimentally obtained spectra are shown in gray solid lines, and the sum of all amide I components in dotted lines. The amide I components corresponding to α-helix, intramolecular β-sheet, and intermolecular β-sheet are marked by circles, inverted triangles, and squares, respectively.

Lipid Order

Using lipid multilayers rather than a single supported bilayer in ATR-FTIR experiments has certain advantages. First, the signal intensity and hence the signal-to-noise ratio of the spectra obtained on multilayers are higher compared to a single bilayer. Second, with a single bilayer, the membrane-reconstituted proteins or peptides can be affected by contacts with the germanium plate. Considering the thickness of our samples (∼1.6 μm) and the repeat distance of POPC or POPC/POPG multilayers of ∼60 Å (i.e., ∼40 Å membrane thickness + ∼20 Å water gap),47 our samples contained ∼260 stacked bilayers, so less than 0.4% of the peptides had a chance to interact with the germanium plate.

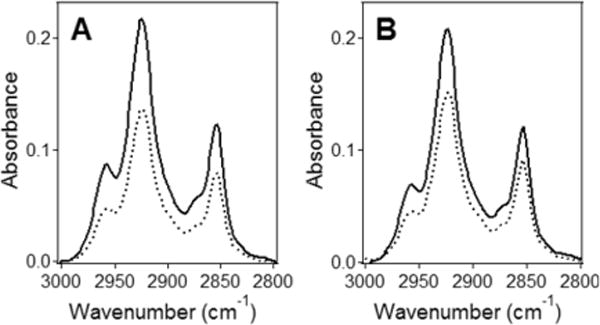

The peptide orientation in supported lipid multilayers makes sense only when the lipid is arranged in lamellar structures with a reasonably good order, mimicking biological membranes. Polarized ATR-FTIR measurements on lipid multilayers in dry, D2O-humidified, and completely hydrated states in the absence and presence of the three peptides have been carried out to determine the lipid order and the effects of the peptides on membrane structure. The order parameter of lipid acyl chains in the absence of peptides was in the 0.30–0.40 range and was only moderately dependent on the membrane hydration state (Table 3). BaxC-KK, and BaxC-LL to a lesser extent, increased the order parameters of POPC/POPG membranes (Figure 4, Table 3).

Table 3.

ATR-FTIR Dichroic Ratios (RL) and the Order Parameters (SL) of Lipid Hydrocarbon Chains under Different Hydration States in the Absence and Presence of Bax Peptidesa

| lipid hydration state | no peptide

|

BaxC-KK

|

BaxC-EE

|

BaxC-LL

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RL | SL | RL | SL | RL | SL | RL | SL | |

| PC, dry | 1.48 ± 0.10 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 1.44 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 1.46 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 1.54 ± 0.09 | 0.31 ± 0.06 |

| PC, humid. | 1.46 ± 0.06 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 1.59 ± 0.07 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 1.45 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 1.51 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.04 |

| PC, hydr. | 1.45 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 1.46 ± 0.05 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 1.48 ± 0.06 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 1.54 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.05 |

| PC/PG, dry | 1.46 ± 0.10 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 1.38 ± 0.08 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 1.65 ± 0.11 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.07 |

| PC/PG, humid. | 1.56 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 1.42 ± 0.07 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 1.44 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.04 |

| PC/PG, hydr. | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 1.22 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 1.38 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 1.35 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.05 |

PC and PG stand for POPC and POPG, humid. and hydr. imply humidified with D2O vapor for 1 h and completely hydrated with bulk aqueous buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes in D2O, pH* 6.8), respectively. The peptides are added at 1:50 peptide/lipid molar ratio.

Figure 4.

The lipid molecules in supported multilayers are well ordered. ATR-FTIR spectra of POPC/POPG (7:3) multilayers on a germanium plate without (A) and with BaxC-KK peptide (B) at a 1:50 peptide/lipid molar ratio, in the presence of bulk D2O-based buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, pH* 6.8), in lipid hydrocarbon chain CH2 stretching region. The estimated thickness of the sample was 1.6 μm. Solid and dashed lines show the spectra at parallel and perpendicular polarizations of the infrared light with respect to the plane of incidence, respectively.

These data indicate that the multilayers had reasonably high lipid order parameter of SL = 0.3–0.4, which in certain cases increased up to 0.6. The order parameters corresponding to disordered acyl chains and those perfectly ordered parallel to the membrane normal are 0.0 and 1.0, respectively. Regarding that the unsaturated bond in the center of the sn-2 chains of POPC and POPG generates deviations from trans configuration, these order parameters for POPC and POPC/POPG membranes indicate a very well ordered membrane structure.33 Polarized ATR-FTIR data thus indicated (i) the lipid was organized in a lamellar structure with a reasonably good lipid order parameter, and (ii) Bax peptides either exerted an ordering effect or no significant effect on the membrane structure. This conclusion accords with our earlier finding that the peptides form membrane pores without disrupting the membrane structure.18

Membrane Insertion of Peptides

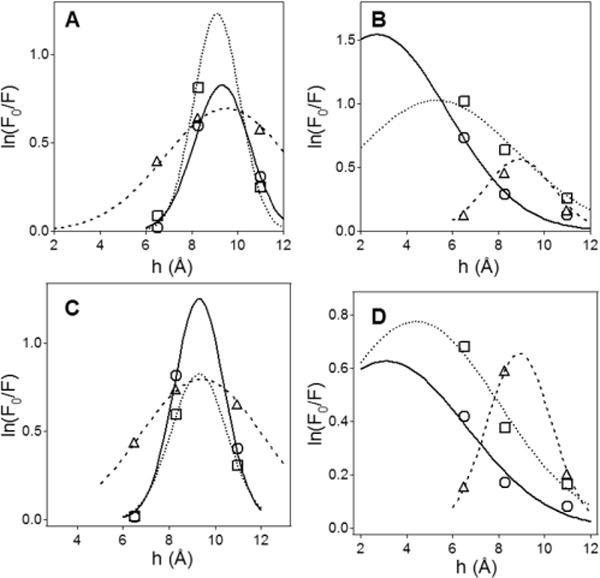

The degree of membrane insertion of the peptides was probed by measuring tryptophan fluorescence quenching by Br2PC lipids brominated at various positions of the sn-2 acyl chain. The peptides were first solubilized in DPC micelles and then reconstituted in POPC or POPC/POPG (7:3) vesicles without or with 10 mol % of each one of the three Br2PCs brominated at 6,7-, or 9,10-, or 11,12-positions, followed by measurements of the fluorescence spectra of the single Trp16 of the peptides. Differential quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by Br2PCs was then used to determine the most probable location of Trp16 relative to the membrane center.19,20 The fluorescence spectra indicate significant and distinct quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by all Br2PCs (Figure 5) and suggest that Trp16 of all three peptides inserts into the membrane hydrophobic core. Results of quantitative analysis of these data are shown in Figure 6 and summarized in Table 4. In the case of POPC membranes, membrane insertion is characterized with a distance from membrane center hm = 9.0–9.5 Å at both 37 and 20 °C; i.e., Trp16 is located within the membrane, not far from the boundary between the membrane hydrophobic core and the polar interfacial region. With POPC/POPG (7:3) membranes, BaxC-KK and BaxC-LL peptides appear to insert significantly deeper into the membrane, reaching depths of ∼3 Å and 5 Å from the membrane center, respectively, while BaxC-EE remains shallowly inserted (Table 4). The parameter S, which is proportional to the extent of the exposure of the fluorophore to the membrane hydrophobic core, and the dispersion of the distribution curves, σ, also profoundly increase in the presence of 30% POPG in membranes for BaxC-KK and BaxC-LL but not for BaxC-EE peptides, consistent with changes in depth of membrane insertion.

Figure 5.

Tryptophan fluorescence of membrane-reconstituted peptides is quenched by brominated lipids. Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence of BaxC-KK (A, B), BaxC-EE (C, D), and BaxC-LL (E, F) by Br2PC lipids brominated at 6,7- (dashed lines), 9,10- (dash-dotted lines), and 11,12-positions (solid lines), at 37 °C. The peptides are reconstituted in POPC (A, C, E) or POPC/POPG (7:3) membranes (B, D, F). Spectra shown in dotted lines correspond to membranes without Br2PC.

Figure 6.

The tryptophan of membrane-reconstituted peptides is inserted into the membrane hydrocarbon region. Dependence of quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by brominated lipids on the distance of bromines from membrane center for POPC (A, C) and POPC/POPG (7:3) membranes (B, D), at 37 °C (A, B) and 20 °C (C, D). Circles, triangles, and squares correspond to BaxC-KK, BaxC-EE, and BaxC-LL peptides, respectively. The bell-shaped curves are simulated based on a Gaussian distribution of tryptophan position along the membrane normal (see Materials and Methods); the peaks of the curves indicate the most probable location of the tryptophan from the membrane center.

Table 4.

Parameters Characterizing Membrane Insertion of Peptides As Determined by Tryptophan Fluorescence Quenching by Brominated Lipidsa

| lipid | BaxC-KK

|

BaxC-EE

|

BaxC-LL

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hm (Å) | S (Å) | σ (Å) | hm (Å) | S (Å) | σ (Å) | hm (Å) | S (Å) | σ (Å) | |

| POPC | 9.3 (9.3) | 2.5 (3.3) | 1.2 (1.2) | 9.5 (9.4) | 4.7 (5.3) | 2.7 (2.7) | 9.1 (9.2) | 3.1 (2.5) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| POPC/POPG | 2.7 (3.1) | 12.0 (5.5) | 3.1 (3.5) | 8.9 (8.9) | 2.1 (2.3) | 1.5 (1.4) | 5.3 (4.4) | 9.0 (7.0) | 3.5 (3.6) |

Values are given for 37 °C and for 20 °C (in parentheses). Standard deviations of all three parameters, as determined in three experiments, are ±1.0 Å or less.

Pore Model

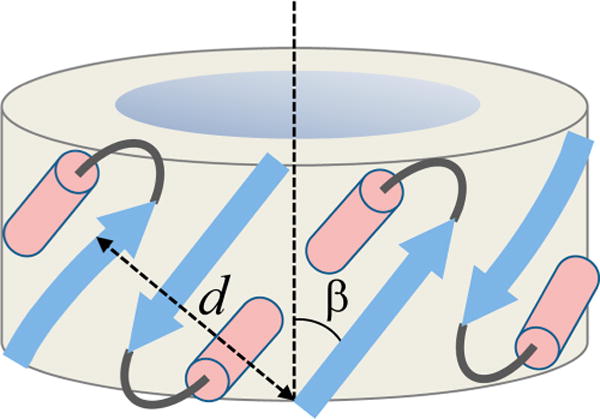

Data on peptide-induced calcein release from lipid vesicles suggested that up to eight peptide molecules assemble to form the final pore structure.18 The present data show that BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE peptides contain 6–8 amino acid residues in α-helical and 8–10 residues in β-strand conformations, whereas BaxC-LL has 4–5 residues in α-helical and 10–11 residues in β-strand conformations (Table 1). To determine the locations of α-helical and β-strand structures in the peptides, peptide secondary structure prediction was conducted using the Internet-based servers Psipred, provided by University College London Department of Computer Science (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/) and Jufo, provided by Professor Jens Meiler’s lab of Vanderbilt University (http://www.meilerlab.org/index.php/servers/show). Both programs predicted similar structures, with N-termini of the peptides in strand and the C-termini in helix conformations: vTIFVAGVLTASLTIWKkmg, vTIFVAGVLTASLTIWEEmg, and vTIFVAGVLTASLTIWLLMg, where lower case and italicized letters indicate unordered and strand structures, respectively, and the rest assume a α-helical structure. Approximately similar fractions of strand and helical structures in BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE and an increased β-strand propensity in BaxC-LL peptide very nicely accord with our FTIR and CD data (Figures 1 and 2, Table 1). Polarized ATR-FTIR data indicated that the strands are tilted at 20–40 degrees from the pore axis and likely are involved in antiparallel β-sheets, assuming the pore central axis makes a 0–20° angle with membrane normal, while α-helices are tilted at 40–60 degrees from membrane normal (Table 2). In the case of BaxC-KK in POPC/POPG membranes, which results in a most efficient vesicle content leakage, the helices and strands are aligned at a similar angle of ∼40 degrees. Furthermore, the tryptophan residue close to the C-terminus of the peptides inserts into POPC membranes to a depth of ∼9 Å from membrane center, and in cases of BaxC-KK and BaxC-LL the presence of 30% POPG results in a deeper membrane insertion (Figure 6, Table 4). Finally, membrane insertion and pore formation does not cause membrane disruption and in certain cases (e.g., BaxC-KK in POPC/POPG membranes) even increases the lipid order (Figure 4, Table 3). These data constitute sufficient constraints to construct a model for the transmembrane pore formed by Bax peptides.

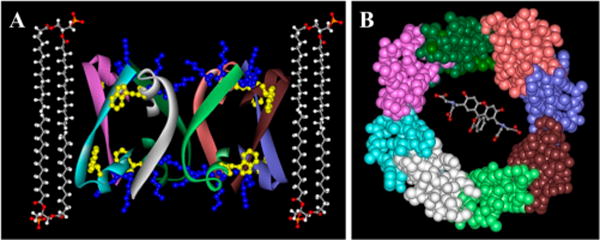

Eight peptide molecules are proposed to arrange in a ring structure, each peptide molecule containing an average of 9 residues in β-strand and 7 residues in α-helix structures, both helices and strands, connected by a turn or a short loop, tilted at ∼40 degrees relative to the pore axis so the helix turns backward into the ring structure (Figure 7). Each ith peptide forms an antiparallel β-sheet with the (i + 1)th peptide and interacts with the (i − 1)th peptide via H-bonding between strand main chain and helix side chains. Note that the C-terminal seven residues of the peptides include threonine, tryptophan, and methionine, all of which have side chains with H-bonding capabilities.48–50 H-bonding between β-strand main chain carbonyls and α-helix side chains, resulting in amide I frequencies around 1620 cm−1 and 1698 cm−1, has been described earlier.51,52 Thus, amide I components at 1638−1634 cm−1 may result from peptide residues involved in interstrand H-bonding and those in the 1630−1620 cm−1 and 1700−1690 cm−1 regions (Figure 1) may be generated by residues that form strand-to-helical side chain H-bonding. As shown in Figure 8, this model allows the two lysines in BaxC-KK peptide to be involved in strong H-bonding with the carbonyl oxygens and/or ionic interactions with the phosphate groups of membrane lipids, as in case of Aβ25–35 peptide53 or the arginine-rich antimicrobial peptide protegrin-1.54 In cases of BaxC-EE, the glutamate residues would most likely be turned toward the aqueous interior of the pore, like in the case of pores formed by GALA peptide,55 while the leucines of BaxC-LL would be oriented inversely, i.e., toward the lipid phase of the membrane. BaxC-KK and BaxC-EE peptides then would form anion- and cation-selective pores, respectively, while BaxC-LL would not exhibit strong ion selectivity; these predictions will be tested in further studies.

Figure 7.

Structural data allow construction of the pore model. Schematic depiction of the pore formed by eight peptide molecules, four of which are shown in a strand–turn–helix conformation, presented as blue arrow, gray arc, and pink cylinder, respectively. Each peptide molecule is oriented relative to its neighbors in an antiparallel sense. The strands are tilted from the pore central axis by β = 30–40 degrees. The repeat distance of the pore structure, i.e., the distance between ith and (i − 2)th strands, perpendicular to the strand axes, is d.

Figure 8.

The molecular model of the pore contains eight peptide molecules and allows efficient transport of calcein. Model for the membrane pore formed by BaxC-KK peptide. Left: Peptide molecules are shown in ribbon format, colored according to peptide monomer. The secondary structure, orientation of strands and helices, and tryptophan insertion into the membrane are based on polarized ATR-FTIR and fluorescence quenching data. Tryptophan 16 and lysines 17 and 18 in each peptide molecule are presented in ball and stick format colored yellow and blue, respectively. Four lipid molecules are shown in ball and stick format, colored according to atom type (carbons gray, oxygens red, hydrogens white, phosphorus orange). Right: Top view of the pore formed by BaxC-KK is shown in a CPK format, colored according to peptide monomer. A calcein molecule is shown within the pore in a ball and stick format, colored according to atom type (see above). Hydrogen atoms in peptide and calcein molecules are omitted.

The pore model shown in Figures 7 and 8 was assessed by preliminary solid state NMR experiments on two selectively 13C-labeled samples of BaxC-KK peptide reconstituted in POPC/POPG (7:3) bilayers: (a) 13C-labeled at carbonyls of both Phe4 and Lys17, and (b) 13C- labeled at carbonyl of Phe4 only. Comparison of the 1D 13C spectra of these samples (Figure S2A of Supporting Information) indicates that the peaks at 173.5 ppm and 178.3 ppm belong to Phe4 and Lys17, respectively. The chemical shift of Phe4 corresponds to a combination of disordered and β-sheet structures, whereas that of Lys17 indicates an α-helical structure.56 Figure S2B shows 2D 13C–13C correlation spectra of sample a. These spectra again indicate Lys17 is in a stable α-helical structure, whereas Phe4 is a mixture of disordered and β-sheet conformations. Additional evidence for this is provided by disappearance of Lys17 resonance in the red spectrum, indicating a slower dynamics likely resulting from its more rigid helical structure as opposed to the more flexible structure of the N-terminal part of the peptide. These data indicate the C-terminal part of the membrane-reconstituted peptide is α-helical, while the N-terminus is in a more flexible β-sheet conformation, consistent with the pore model shown in Figures 7 and 8. Off-diagonal cross-peaks between Phe4 and Lys17 suggest close proximity between the two 13C-labeled carbonyl sites (<6 Å), in agreement with the antiparallel arrangement of peptide molecules in the proposed pore structure. The NMR data also provide evidence against possible heterogeneity of the peptide-lipid samples. If the sample was heterogeneous, with a fraction in β-sheet conformation and the rest in α-helix conformation, the sample where only Phe4 is 13C-labeled would show both α-helix and β-sheet signals, whereas the α-helix signal appears only when Lys17 is 13C-labeled, indicating the C-terminal part of the peptide is α-helical and the N-terminal part is in a more flexible conformation, forming a β-sheet but not an α-helical structure.

A deeper insertion of Trp16 of BaxC-KK into anionic POPC/POPG membranes as compared to zwitterionic POPC membranes evidently results from changes in both the secondary structure and the orientation of the peptide. Formation of a longer α-helix with a smaller tilt angle and a shorter β-strand with a larger tilt angle (Tables 1 and 2) may contribute to this effect. In the case of BaxC-LL, smaller changes in the peptide secondary structure and orientation are caused by 30% POPG (Tables 1 and 2). On the basis of data of Table 1, the change in the membrane insertion depth of BaxC-LL (Table 4) caused by 30% POPG can be attributed to a turn-to-helix transition of three amino acid residues between strand and helical segments and unwinding of two helical residues at the C-terminal end of the peptide. The structure and orientation of BaxC-EE appear to be less sensitive to the membrane charge, and hence this peptide does not exhibit considerable differences in insertion into POPC or POPC/POPG membranes (Tables 1, 2 and 4).

How does the proposed pore structure match the hydrophobic thickness of the membrane? Can the pore formed by eight peptides pass molecules as large as calcein, which itself can be modeled as a prolate ellipsoid of revolution with semiaxes of ∼9 Å and ∼3 Å? To answer these questions we need to estimate the pore dimensions. Given a Cα–Cα distance of 3.445 Å along the strand axis for a peptide in an antiparallel β-sheet structure,57 nine residues in the strand, and an angle between strand axis and the pore central axis β = 30 to 40 degrees (Table 2), the pore height is 23.7 to 26.8 Å, which is in good agreement with the membrane hydrophobic core thickness.47,54 The pore radius can be estimated based on the schematic model shown in Figure 7 and known interhelix and interstrand distances. Figure 7 shows that the repeat distance of the pore oligomeric structure along the cylindrical surface and perpendicular to the pore central axis is l = d/cos β. For an octameric structure, composed of four repeating antiparallel dimers, the pore perimeter would be 4d/cos β, and the radius r = 2d/π cos β. The closest distance between the helical axes of α-helices involved in “line-to-line” interactions is 9.6 Å,58 and the interstrand distance in antiparallel β-sheets is 4.73 Å,57 so the helix-to-strand distance would be 0.5(9.6 Å + 4.73 Å) = 7.16 Å and hence d = 2 × 7.16 Å + 4.73 Å = 19 Å. Finally, if the strand tilt angle varies between 30 and 40 degrees, then the radius of a cylindrical pore formed by the backbone atoms is between 14.0 Å and 15.8 Å. The side chains will form a 4–5 Å thick layer, thus resulting in a central pore cavity approximately 20–22 Å wide (in diameter). The pore can transfer calcein molecules in a hydrated state, which would exclude any “desolvation penalty” effects resulting in an efficient membrane permeation process, as confirmed by our earlier data.18

A wide variety of naturally occurring or synthetic peptides have been shown to form membrane pores. While the main mechanisms involve transmembrane α-helical bundles55,59–62 or β-barrel-like structures,53,62 peripheral helical or β-sheet structures formed at the membrane surface can also cause membrane permeabilization.59,63,64 Oligomeric states of these structures varying between 3 and 10 have been reported.53,55,61,62,65,66 More hydrophobic peptides form a “barrel-stave” structure while polar and (positively) charged peptides generally cover the membrane surface by a “carpet” mechanism,16 although exceptions from these rules can occur. The pore diameters were estimated to be as small as 3.5–4.0 Å for a 11-residue fragment of the Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide that has been modeled as eight-stranded β-barrels in membranes,53 as large as 35–45 Å for bee venom melittin,65 and of intermediate sizes.55,67 Our data are consistent with an octameric membrane pore structure with an inner diameter of ∼20–22 Å. The cationic wild-type BaxC-KK, anionic BaxC-EE, and the neutral BaxC-LL peptides all adopt relatively similar secondary structures in the membrane environment and form efficient pores in both zwitterionic and anionic membranes. This indicates that hydrophobic peptide-lipid interactions play a major role, and therefore the pores are formed by a “barrel-stave” rather than the “carpet” mechanism, which is also confirmed by significant insertion of the peptide into the membrane hydrophobic core (Figure 6, Table 4). The ability of the relatively short peptides to form large transmembrane pores is supported by the “α/β-ring” structure (Figures 7 and 8), which is more efficient in terms of pore formation than pure α-helical or β-sheet structures. The intervening helical structures between eight β-strands increase the overall perimeter and hence the radius of the pore. It is important to note that although the proposed pore architecture is consistent with the set of biophysical data presented here, still it should be considered as a working model rather than a precise three-dimensional structure; further work will be required to achieve an atomic-resolution structure of the pore in lipid membranes. Nonetheless, considering that bacterial and mitochondrial β-barrel porins with molecular mass of 30–40 kDa and containing 14–19 strands form 10–15 Å wide transmembrane pores,46 the capability of short, Bax-derived peptides to form efficient membrane pores is quite remarkable and can potentially be used to design peptide-based cytotoxic agents.17

CONCLUSIONS

Here the molecular basis for membrane pore formation by the wild-type Bax C-terminal peptide and two mutants has been analyzed by biophysical methods. Combined data on the secondary structure, angular orientation, depth of membrane insertion, together with the oligomeric state of the pore determined earlier,18 are consistent with an α/β-ring structure that involves eight peptide molecules in a strand-turn-helix conformation. Considering the significant fraction of β-strand structure in the membrane-inserted peptides, which deviates from the α-helical structure of the C-terminus of Bax, the behavior of the isolated peptide, including its membrane pore forming mechanism, is likely to be different from that of Bax protein. It is remarkable, however, that the C-terminal peptide of Bax, which has long been suspected to be responsible for membrane binding and permeabilization, indeed is a potent membrane pore former. On the other hand, our results, including the proposed α/β-ring structure, suggest a new mechanism of membrane pore formation that peptides can utilize to perforate cellular membranes. These findings could facilitate developing cytotoxic peptide-based molecular tools for cell membrane permeabilization and killing of unwanted cells such as bacteria, fungi, or cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Financial support from the National Institutes of Health Grant GM083324 is gratefully acknowledged.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ATR-FTIR

attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared

- BaxC-KK

C-terminal peptide of wild-type Bax protein: Ac-VTIFVAGVLTASLTIWKKMG-NH2)

- BaxC-EE

C-terminal peptide of Bax protein with two lysines replaced by glutamates

- BaxC-LL

C-terminal peptide of Bax protein with two lysines replaced by leucines

- BCL-2

B cell lymphoma 2

- Br2PC

1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl-dibromo-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- CD

circular dichroism

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DPC

dodecylphosphocholine

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- LUV

large unilamellar vesicle

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Figure S1. The wild-type and mutant peptides in phospholipid membranes exhibit a α/β-type secondary structure; Figure S2. Solid state NMR data support the proposed pore structure. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tait SW, Green DR. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:621–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westphal D, Dewson G, Czabotar PE, Kluck RM. Molecular biology of Bax and Bak activation and action. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell. 2000;103:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolter KG, Hsu YT, Smith CL, Nechushtan A, Xi XG, Youle RJ. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nechushtan A, Smith CL, Hsu YT, Youle RJ. Conformation of the Bax C-terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. EMBO J. 1999;18:2330–2341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antignani A, Youle RJ. How do Bax and Bak lead to permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boohaker RJ, Zhang G, Carlson AL, Nemec KN, Khaled AR. BAX supports the mitochondrial network, promoting bioenergetics in nonapoptotic cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C1466–C1478. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00325.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Sáez AJ, Coraiola M, Serra MD, Mingarro I, Menestrina G, Salgado J. Peptides derived from apoptotic Bax and Bid reproduce the poration activity of the parent full-length proteins. Biophys J. 2005;88:3976–3990. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Saez AJ, Coraiola M, Serra MD, Mingarro I, Müller P, Salgado J. Peptides corresponding to helices 5 and 6 of Bax can independently form large lipid pores. FEBS J. 2006;273:971–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valero JG, Sancey L, Kucharczak J, Guillemin Y, Gimenez D, Prudent J, Gillet G, Salgado J, Coll JL, Aouacheria A. Bax-derived membrane-active peptides act as potent and direct inducers of apoptosis in cancer cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:556–564. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torrecillas A, Martínez-Senac MM, Ausili A, Corbalán-García S, Gómez-Fernández JC. Interaction of the C-terminal domain of Bcl-2 family proteins with model membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:2931–2939. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Senac MM, Corbalan-García S, Gomez- Fernández JC. Conformation of the C-terminal domain of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and mutants and its interaction with membranes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9983–9992. doi: 10.1021/bi010667d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ausili A, Torrecillas A, Martínez-Senac MM, Corbalán-García S, Gómez-Fernández JC. The interaction of the Bax C-terminal domain with negatively charged lipids modifies the secondary structure and changes its way of insertion into membranes. J Struct Biol. 2008;164:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ausili A, de Godos A, Torrecillas A, Corbalán-García S, Gómez-Fernández JC. The interaction of the Bax C-terminal domain with membranes is influenced by the presence of negatively charged phospholipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1924–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangoni ML, Shai Y. Short native antimicrobial peptides and engineered ultrashort lipopeptides: similarities and differences in cell specificities and modes of action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2267–2280. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0718-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boohaker RJ, Zhang G, Lee MW, Nemec KN, Santra S, Perez JM, Khaled AR. Rational development of a cytotoxic peptide to trigger cell death. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2012;9:2080–2093. doi: 10.1021/mp300167e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg P, Nemec KN, Khaled AR, Tatulian SA. Transmembrane pore formation by the carboxyl terminus of Bax protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.London E, Ladokhin AS. Measuring the depth of amino acid residues in membrane-inserted peptides by fluorescence quenching. Curr Top Membr. 2002;52:89–115. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pande AH, Qin S, Nemec KN, He X, Tatulian SA. Isoform-specific membrane insertion of secretory phospholipase A2 and functional implications. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12436–12447. doi: 10.1021/bi060898q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntosh TJ, Holloway PW. Determination of the depth of bromine atoms in bilayers formed from bromolipid probes. Biochemistry. 1987;26:1783–1788. doi: 10.1021/bi00380a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinogradova O, Sönnichsen F, Sanders CR., II On choosing a detergent for solution NMR studies of membrane proteins. J Biomol NMR. 1998;11:381–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1008289624496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Lu W, Hong M. The membrane-bound structure and topology of a human α-defensin indicate a dimer pore mechanism for membrane disruption. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9770–9782. doi: 10.1021/bi101512j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dvinskikh SV, Castro V, Sandstrom D. Heating caused by radiofrequency irradiation and sample rotation in 13C magic angle spinning NMR studies of lipid membranes. Magn Reson Chem. 2004;42:875–881. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. 13C-1H dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;344:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigano C, Goormaghtigh E, Ruysschaert J-M. Detection of structural and functional asymmetries in P-glycoprotein by combining mutagenesis and H/D exchange measurements. Chem Phys Lipids. 2003;122:121–135. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasoe PK, Long FA. Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J Phys Chem. 1960;64:188–190. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh D. Quantitation of secondary structure in ATR infrared spectroscopy. Biophys J. 1999;77:2630–2637. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77096-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venyaminov SY, Kalnin NN. Quantitative IR spectrophotometry of peptide compounds in water (H2O) solutions. II Amide absorption bands of polypeptides and fibrous proteins in α-, β-, and random coil conformations. Biopolymers. 1990;30:1259–1271. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides and proteins. Advan Protein Chem. 1986;38:181–364. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haris PI, Chapman D. The conformational analysis of peptides using Fourier transform IR spectroscopy. Biopolymers. 1995;37:251–263. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tatulian SA. Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: A method of choice for studying membrane proteins and lipids. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11898–11907. doi: 10.1021/bi034235+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh D. Infrared dichroism of twisted β-sheet barrels. The structure of E. coli outer membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:803–808. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brauner JW, Mendelsohn R, Prendergast FG. Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared studies of the interaction of melittin, two fragments of melittin, and delta-hemolysin with phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8151–8158. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheu SY, Yang DY, Selzle HL, Schlag EW. Energetics of hydrogen bonds in peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12683–12687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133366100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivella M, Deupi X, Govaerts C, Pardo L. Influence of the environment in the conformation of alpha-helices studied by protein database search and molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2002;82:3207–3213. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75663-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarrold MF. Helices and sheets in vacuo. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:1659–1671. doi: 10.1039/b612615d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bai Y, Englander SW. Hydrogen bond strength and β-sheet propensities: the role of a side chain blocking effect. Proteins. 1994;18:262–266. doi: 10.1002/prot.340180307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flach CR, Prendergast FG, Mendelsohn R. Infrared reflection-absorption of melittin interaction with phospholipid monolayers at the air/water interface. Biophys J. 1996;70:539–546. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79600-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Circular dichroism of peptides and proteins. In: Berova N, Nakanishi K, Woody RW, editors. Circular Dichroism: Principles and Applications. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, N.J.: 2000. pp. 601–620. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen YH, Yang JT, Chau KH. Determination of the helix and β form of proteins in aqueous solution by circular dichroism. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3350–3359. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lees JG, Miles AJ, Wien F, Wallace BA. A reference database for circular dichroism spectroscopy covering fold and secondary structure space. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1955–1962. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Páli T, Marsh D. Tilt, twist, and coiling in β-barrel membrane proteins: relation to infrared dichroism. Biophys J. 2001;80:2789–2797. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleinschmidt JH. Folding kinetics of the outer membrane proteins OmpA and FomA into phospholipid bilayers. Chem Phys Lipids. 2006;141:30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeth K, Thein M. Porins in prokaryotes and eukaryotes: common themes and variations. Biochem J. 2010;431:13–22. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogel M, Münster C, Fenzl W, Salditt T. Thermal unbinding of highly oriented phospholipid membranes. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:390–393. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gregoret LM, Rader SD, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE. Hydrogen bonds involving sulfur atoms in proteins. Proteins. 1991;9:99–107. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu W, Cross TA. Tryptophan hydrogen bonding and electric dipole moments: Functional roles in the gramicidin channel and implications for membrane proteins. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14147–14155. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biswal HS, Wategaonkar S. Nature of the N-H…S hydrogen bond. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:12763–12773. doi: 10.1021/jp907658w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arrondo JLR, Muga A, Castresana J, Bernabeu C, Goñi FM. An infrared spectroscopic study of β-galactosidase in aqueous solutions. FEBS Lett. 1989;252:118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arrondo JLR, Muga A, Castresana J, Goñi FM. Quantitative studies of the structure of proteins in solution by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1993;59:23–56. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(93)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang Z, Luo Y, Zhang Y, Wei G. Interactions of Aβ25–35 β-barrel-like oligomers with anionic lipid bilayer and resulting membrane leakage: an all-atom molecular dynamics study. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:1165–1174. doi: 10.1021/jp107558e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khandelia H, Kaznessis YN. Structure of the antimicrobial β-hairpin peptide protegrin-1 in a DLPC lipid bilayer investigated by molecular dynamics simulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parente RA, Nir S, Szoka FC., Jr Mechanism of leakage of phospholipid vesicle contents induced by the peptide GALA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8720–8728. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wishart DS, Sykes BD. The 13C chemical-shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arnott S, Dover SD, Elliott A. Structure of β-poly-L-alanine: refined atomic co-ordinates for an anti-parallel β-pleated sheet. J Mol Biol. 1967;30:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee S, Chirikjian GS. Interhelical angles and distance preferences in globular proteins. Biophys J. 2004;86:1105–1117. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oren Z, Shai Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 1998;47:451–463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<451::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwarz G, Reiter R. Negative cooperativity and aggregation in biphasic binding of mastoparan X peptide to membranes with acidic lipids. Biophys Chem. 2001;90:269–277. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nieva JL, Agirre A, Nir S, Carrasco L. Mechanisms of membrane permeabilization by picornavirus 2B viroporin. FEBS Lett. 2003;552:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thundimadathil J, Roeske RW, Jiang H-Y, Guo L. Aggregation and pore-like channel activity of a β-sheet peptide. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10259–10270. doi: 10.1021/bi0508643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gregory SM, Pokorny A, Almeida PF. Magainin 2 revisited: a test of the quantitative model for the all-or-none permeabilization of phospholipid vesicles. Biophys J. 2009;96:116–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhargava K, Feix JB. Membrane binding, structure, and localization of cecropin-mellitin hybrid peptides: a site-directed spin-labeling study. Biophys J. 2004;86:329–336. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74108-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park SC, Kim JY, Shin SO, Jeong CY, Kim MH, Shin SY, Cheong GW, Park Y, Hahm KS. Investigation of toroidal pore and oligomerization by melittin using transmission electron microscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agner G, Kaulin YA, Gurnev PA, Szabo Z, Schagina LV, Takemoto JY, Blasko K. Membrane-permeabilizing activities of cyclic lipodepsipeptides, syringopeptin 22A and syringomycin E from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae in human red blood cells and in bilayer lipid membranes. Bioelectrochemistry. 2000;52:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0302-4598(00)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casallanovo F, de Oliveira FJ, de Souza FC, Ros U, Martínez Y, Pentón D, Tejuca M, Martínez D, Pazos F, Pertinhez TA, Spisni A, Cilli EM, Lanio ME, Alvarez C, Schreier S. Model peptides mimic the structure and function of the N-terminus of the pore-forming toxin sticholysin II. Biopolymers. 2006;84:169–180. doi: 10.1002/bip.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.