Abstract

A functional rs4245739 A>C single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) locating in the MDM43’-untranslated (3’-UTR) region creates a miR-191-5p or miR-887-3p targeting sites. This change results in decreased expression of oncogene MDM4. Therefore, we examined the association between this SNP and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) risk as well as its regulatory function in SCLC cells. Genotypes were determined in two independent case-control sets consisted of 520SCLC cases and 1040 controls from two regions of China. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by logistic regression. The impact of the rs4245739 SNP on miR-191-5p/miR-887-3p mediated MDM4 expression regulation was investigated using luciferase reporter gene assays. We found that the MDM4 rs4245739AC and CC genotypes were significantly associated with decreased SCLC susceptibility compared with the AA genotype in both case-control sets (Shandong set: OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.32–0.89, P = 0.014; Jiangsu set: OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.26–0.879, P = 0.017). Stratified analyses indicated that there was a significantly multiplicative interaction between rs4245739 and smoking (P interactioin = 0.048). After co-tranfection of miRNAs and different allelic-MDM4 reporter constructs into SCLC cells, we found that the both miR-191-5p and miR-887-3p can lead to significantly decreased MDM4 expression activities in the construct with C-allelic 3’-UTR but not A-allelic 3’-UTR, suggesting a consistent genotype-phenotype correlation. Our data illuminate that the MDM4rs4245739SNP contributes to SCLC risk and support the notion that gene 3’-UTR genetic variants, impacting miRNA-binding, might modify SCLC susceptibility.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading causes of cancer death in the world, with more than1,000,000 deaths per year [1]. Lung cancer is commonly classified as small-cell lung cancer(SCLC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Though accounting for only approximately twenty percent of all lung cancer cases, SCLC is much more aggressive compared to NSCLC [2,3]. As a malignancy with poor prognosis, SCLC shows high growth fraction, rapid doubling time, and early development of widespread metastases [2,3]. When diagnosed, most SCLC patients have metastasis and bad prognosis if left untreated [3]. Accumulated epidemiological evidences indicate that heavy tobacco smoking is a main environmental risk-factor of this disease [2,3]. Recent progresses on genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revealed that multiple novel genetic variations are associated with lung cancer susceptibility [4–12]. However, most studies examined both lung cancer subtypes or only focused on NSCLC. Interestingly, the majority of identified risk loci do not significantly influence the risk of lung cancer differentially by histology, indicating that there might be different genetic makeup impacts risk of SCLC or NSCLC [4–12]. Therefore, discovery of novel SCLC-risk-associated SNPs might be a potentially valuable path towards illuminating etiology of SCLC.

MDM4, also known as MDMX or HDMX, is a structurally homologous protein of MDM2. MDM4 shares an NH2-terminal P53-binding domain with MDM2 and can inhibit activities of P53 in various malignancies [13–17]. As the guardian of human genome, P53 functions at the center of a complex molecular network to mediate tumor suppression. As a well-known oncogene, overexpressed MDM4 in human tumors including lung cancer led to depressed P53 activities and, thus, tumorigenesis. In line with this, mouse model with overexpressed MDM4 via transgenetic technology showed spontaneous carcinogenesis during their lifespan [18].

There is an MDM43’-untranslatedregion (3’-UTR) rs4245739A>C SNP locating in the target binding site for two miRNAs (miR-191-5p and miR-887-3p) [19,20]. miR-191-5p and miR-887-3p could selectively bind to MDM43’-UTR with the rs4245739C allele but not 3’-UTR with the A allele. This allelic miRNAs’ binding leads to elevated expression levels of MDM4 mRNA and/or protein among rs4245739A allele carriers with cancers [19–22]. Two GWAS showed that the MDM4 rs4245739 A-allele is significantly associated with increased risk of both prostate cancer and breast cancer [23,24]. Several case-control studies using candidate gene strategy also confirmed the positive association between this polymorphism and susceptibility of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in different ethnic populations [20,22,25,26]. However, the involvement of this functional SNP in SCLC is still largely unknown. Considering the essential role of MDM4 in carcinogenesis, we hypothesized that the MDM4rs4245739 SNP may contribute to SCLC susceptibility via allelic regulation ofmiR-191-5p and/or miR-887-3p binding affinity and, thus, MDM4 expression. In the current study, we conducted a two-stage case-control study of SCLC recruited from Jinan city (Shandong Province, China) and Huaian city (Jiangsu Province, China). Furthermore, to validate the biological function of this polymorphism, we investigated the allelic regulation of miR-191-5p and miR-887-3p on MDM4 in SCLC cells.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

This study consisted of two case-control sets: (i) Shandong case-control set: 320 SCLC patients from Shandong Cancer Hospital, Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (Jinan, Shandong Province, China) and sex- and age-matched (±5 years) 640 controls. Patients were recruited between June 2009 and November 2014 at Shandong Cancer Hospital. Control subjects were randomly selected from a pool of 4500 individuals from a community cancer-screening program for early detection of cancer conducted in Jinan city as described in detail previously [22]. (ii) Jiangsu case-control set: 200 SCLC patients from Huaian No. 2 Hospital (Huaian, Jiangsu Province, China) and sex- and age-matched 400 controls. Patients were consecutively recruited between January 2009 and January 2015 at Huaian No. 2 Hospital. Controls were cancer-free individuals selected from a community cancer-screening program (3600 individuals) for early detection of cancer conducted in Huaian city as described in detail previously [22]. Individuals who smoked one cigarette per day for over 1 year were considered as smokers [22]. All subjects were unrelated ethnic Han Chinese. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Huaian No. 2 Hospital and Shandong Cancer Hospital, Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject at recruitment.

SNP genotyping

PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) was utilized to determine MDM4 rs4245739A>C genotypes as described in detail previously [22,25,26]. In brief, the primers used for amplifying DNA segments with the rs4245739 site (the mismatch base is underlined) were 5′-AAGACTAAAGAAGGCTGGGG-3′ and 5′-TTCAAATAATGTGGTAAGTGACC-3′. Restriction enzyme MspI (New England Biolabs) was used to digest the PCR products and distinguish the rs4245739 genotypes. A 10% random sample was reciprocally examined by different person, and the reproducibility was 98.7%. Additionally, a 5% random samples were also tested via Sanger sequencing, and the reproducibility was 100%.

Plasmid construction

The MDM4 rs4245739A and rs4245739C allelic reporter constructs were prepared by amplifying part of the MDM43’-UTR region from subjects homozygous for the rs4245739AA or rs4245739CC genotype. The PCR primers used were as follows: 5′-AACTCTAGAGGTAGTACGAACATAAAAATGC-3′ and 5′-AACTCTAGACTGCATAAAGTAATCCATGG-3′, which includes the Xba I restriction site (underlined sequences). The PCR products were digested with Xba I (New England Biolabs) and ligated, respectively, into an appropriately digested pGL3-control vector (Promega). The constructs were designated aspGL3-rs4245739A and pGL3b-rs4245739C, respectively. The inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Dual luciferase reporter gene assay

A firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-control, pGL3-rs4245739A or pGL3-rs4245739C), a renilla luciferase vector (pRL-SV40, Promega) plus 30 nMsmall RNAs (miR-191-5p mimics, miR-887-3p mimics or negative control RNAs) (Genepharma, Guangzhou, China) were co-transfected into SCLCH446 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Luciferase activity was determined at 48h after transfection using a luciferase assay system (Promega) as previously described [27–29]. Three independent transfection experiments were performed and each was done in triplicate. Fold increase was calculated by defining the activity of empty pGL3-control vector as 1.

Statistical analyses

As described in detail previously [22, 30–32], the differences in demographic variables and genotype distributions of MDM4 rs4245739 SNP between SCLC cases and controls were calculated using Pearson’s χ2 test. Associations between MDM4 rs4245739 genotypes and SCLC risk were estimated by odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) computed using unconditional logistic regression model. All ORs were adjusted for age, sex and smoking status, where it was appropriate. We tested the null hypotheses of multiplicative gene-covariate interaction and evaluated departures from multiplicative interaction models by including main effect variables and their product terms in the logistic regression model [30–32]. A P value of less than 0.05 was used as the criterion of statistical significance, and all statistical tests were two-sided. All analyses were performed with SPSS software package (Version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Allelic frequencies and genotype distributions of MDM4 rs4245739SNP

The median age was 57 years (range, 25–82 years for Shandong set; range, 23–79 years for Jiangsu set) for the patients and 57 years (range, 19–80 years for Shandong set; range, 20–81 years for Jiangsu set) for the controls(Shandong set: P = 0.615; Jiangsu set: P = 1.000). There was no significant difference between cases and controls in sex distribution (Shandong set: 78.4% males incases vs. 76.4% in controls; P = 0.480; Jiangsu set: 74.0% males incases vs. 71.3% in controls; P = 0.479). This indicates that the frequency matching was adequate (Table 1). However, more smokers among SCLC patients were found in Shandong case-control set compared with control subjects (Shandong set: 77.8% vs. 34.2%, P<0.001). Similarly, there are more SCLC patients who smoking than controls in Jiangsu set (78.5% vs. 21.5%, P<0.001). Additionally, more patients with limited disease were observed than among ones with extensive disease in two sets (Shandong set: 56.9% vs. 43.1%; Jiangsu set: 56.5% vs. 43.5%).

Table 1. Distribution of selected characteristics among SCLC cases and controls.

| Variable | Shandong set | Jiangsu set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | P a | Cases | Controls | P a | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) | |||

| 320 | 640 | 200 | 400 | |||

| Age (year) b | 0.615 | 1.000 | ||||

| ≤57 | 156(48.9) | 301(47.0) | 99(49.5) | 198(49.5) | ||

| >57 | 164(51.2) | 339(53.0) | 101(50.5) | 202(50.5) | ||

| Sex | 0.480 | 0.479 | ||||

| Male | 251(78.4) | 489(76.4) | 148(74.0) | 285(71.3) | ||

| Female | 69(21.6) | 151(23.6) | 52(26.0) | 115(28.7) | ||

| Smoking status | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 249(77.8) | 219(34.2) | 157(78.5) | 113(28.3) | ||

| No | 71(22.2) | 421(65.8) | 43(21.5) | 287(71.8) | ||

| Clinical stage c | ||||||

| Limited | 182(56.9) | 113(56.5) | ||||

| Extensive | 138(43.1) | 87(43.5) |

Note: SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

aTwo-sided χ2 test.

bMedian ages of patients for Shandong set and Jiangsu set are 57 years.

cClassified according to the Veterans’ Administration Lung Study Group.

As shown in Table 2, the frequency for the MDM4 rs4245739 C allele was 0.038 and 0.073among SCLC patients and healthy controls from Shandong set, and 0.043 and 0.101 from Jiangsu set. All observed genotype frequencies in both SCLC cases and controls conform to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Distributions of these MDM4 genotypes were then compared among SCLC cases and controls. The frequencies of MDM4 rs4245739 AA and AC or CC genotypes among patients were significantly different from those among controls in Shandong set (χ2 = 10.70, P = 0.005, df = 2) (Table 2). Similarly, the frequencies of MDM4 rs4245739 AA and AC or CC genotypes among cases were significantly different from those among control subjects in Jiangsu set (χ2 = 12.84, P = 0.002, df = 2) (Table 2).

Table 2. Genotype frequencies of MDM4rs4245739A>C polymorphism among patients and controls and their association with SCLC risk.

| Genotypes | MDM4 rs4245739A>C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | OR a (95% CI) | P | ||

| Shandong set | n = 320 | n = 640 | |||

| AA | 297(92.6) | 548(85.6) | Reference | ||

| AC | 22(7.1) | 90(14.1) | 0.52(0.31–0.87) | 0.013 | |

| CC | 1(0.3) | 2(0.3) | NC | NC | |

| AC+CC | 23(7.4) | 92(14.4) | 0.53(0.32–0.89) | 0.014 | |

| Jiangsu set | n = 200 | n = 400 | |||

| AA | 183(91.5) | 321(80.3) | Reference | ||

| AC | 17(8.5) | 77(19.3) | 0.48(0.26–0.88) | 0.019 | |

| CC | 0(0) | 2(0.4) | NC | NC | |

| AC+CC | 17(8.5) | 79(19.7) | 0.47(0.26–0.87) | 0.017 | |

| Total | n = 520 | n = 1040 | |||

| AA | 480(92.3) | 869(83.6) | Reference | ||

| AC | 39(7.5) | 167(16.1) | 0.49(0.32–0.75) | 0.001 | |

| CC | 1(0.2) | 4(0.4) | NC | NC | |

| AC+CC | 40(7.7) | 171(16.5) | 0.50(0.32–0.76) | 0.001 |

Note: SCLC, small cell lung cancer; NC, not calculated; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

aData were calculated by logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, and smoking status.

Association between MDM4 rs4245739SNP and SCLC risk

Associations between genotypes of MDM4 rs4245739 A>C polymorphism and SCLC risk were calculated using unconditional logistic regression analyses (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, the MDM4 rs4245739 C allele acts as a protective allele of SCLC. Subjects with the AC genotype had an OR of 0.52 (95% CI = 0.31–0.87, P = 0.013) for developing SCLC, compared with subjects with the AA genotype. Significantly decreased SCLC risk was also observed among rs4245739 AC or CC carriers compared to the AA carriers (OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.32–0.89, P = 0.014). The associations of SCLC risk with the MDM4 rs4245739SNP were further validated in an independent Jiangsu case-control set. A significantly decreased SCLC risk was also associated with rs4245739 (AC: OR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.26–0.88, P = 0.019;AC or CC: OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.26–0.87, P = 0.017). In the pooled analyses, we found that the rs4245739 AC genotype had a 0.49-folddecreased risk for SCLC compared with the AA genotype (95% CI = 0.32–0.75, P = 0.001), and the rs4245739 AC or CC genotype had a 0.50-folddecreased risk compared with the AA genotype (95% CI = 0.32–0.76, P = 0.001) (Table 2). All ORs were adjusted for sex, age and smoking status.

We further examined the SCLC risk associated with the MDM4rs4245739genotypes by stratifying for age, sex, smoking status and disease stage using the pooled data of two Chinese case-control sets (Table 3). In stratified analyses with age, rs4245739AC and CC genotypes were significantly associated with decreased risk in subjects aged 57 years or younger (OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.21–0.74, P = 0.003), but not in subjects aged older than 57 years (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.35–1.15, P = 0.134). There was no significant gene-age interaction (P interaction = 0.274). A significantly decreased risk of SCLC was associated with AC and CC genotypes only among females (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.15–0.74, P = 0.007), but not among males (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.38–1.06, P = 0.083), compared with the MDM4rs4245739 AA genotype. No significant gene-sex interaction was observed (P interaction = 0.135). We did not find significantly decreased risk (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.42–1.28, P = 0.274) for the carriers with AC and CC genotypes compared with individuals with the AA genotype in smokers. However, thers4245739AC and CC genotypes did show a 0.30-fold decreased risk to develop SCLC (95% CI = 0.14–0.64, P = 0.002) compared with the AA genotype in nonsmokers. A multiplicative gene—smoking interaction existed (P interactioin = 0.048). Associations between rs4245739 AC and CC genotypes and SCLC risk were observed in both patients with the limited stage disease (OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.32–0.84, P = 0.008) or the extensive stage disease (OR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.24–0.97, P = 0.040) (Table 3).

Table 3. Association between MDM4rs4245739A>C variant andSCLC risk stratified by selected variables.

| Variable | MDM4 rs4245739A>C | P interaction c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA a | AC+CC a | OR b (95% CI) | P | ||

| Age (year) | 0.274 | ||||

| ≤57 | 237/396 | 18/103 | 0.40(0.21–0.74) | 0.003 | |

| >57 | 243/473 | 22/68 | 0.63(0.35–1.15) | 0.134 | |

| P heterogeneity | 0.180 | 0.079 | |||

| Sex | 0.135 | ||||

| Male | 369/684 | 30/90 | 0.63(0.38–1.06) | 0.083 | |

| Female | 111/185 | 10/81 | 0.33(0.15–0.74) | 0.007 | |

| P heterogeneity | 0.435 | 0.010 | |||

| Smoking status | 0.048 | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 105/572 | 9/136 | 0.30(0.14–0.64) | 0.002 | |

| Smoker | 375/297 | 31/35 | 0.73(0.42–1.28) | 0.274 | |

| P heterogeneity | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Stage | NC | ||||

| Limited | 270/869 | 25/171 | 0.52(0.32–0.84) | 0.008 | |

| Extensive | 210/869 | 15/171 | 0.48(0.24–0.97) | 0.040 | |

| P heterogeneity | 0.015 | 0.135 |

Note: SCLC, small cell lung cancer; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NC, not calculated.

aNumber of case patients with genotype/number of control subjects with genotype.

bData were calculated by logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, and smoking status, where it was appropriate.

c P values for gene-environment interaction were calculated using the multiplicative interaction term in SPSS software.

Functional relevance ofrs4245739 on miRNA-mediated MDM4 regulation

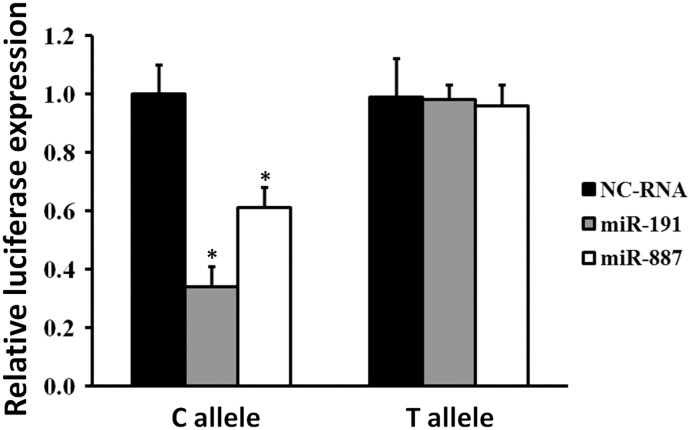

SNPrs4245739A>C could lead to higher affinity between miR-191-5p/miR-887-3p and MDM4mRNA and decreased MDM4expression in multiple malignancies [19–22]. However, its impacts on MDM4 regulation in SCLC are still unclear. As a result, we examined whether there is an allele-specific effect of rs4245739polymorphismon MDM4 expression in SCLC cells by miR-191-5p and miR-887-3p. Relative luciferase expression assays indicated that miR-191-5p can significant lower luciferase activities in SCLC H446 cells transfected with rs4245739C allelic reporter constructs compared to negative control RNAs(P = 0.003) (Fig 1). Similarly, miR-887-3p also regulates MDM4 3’-UTR region with significantly lower luciferase activities in H446 cells expressing rs4245739C allelic constructs compared to negative control RNAs (P = 0.014) (Fig 1). However, there was no such depression in H446 cells with transfection of rs4245739A allelic reporter constructs by both miRNAs mimics (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Transient luciferase reporter gene expression assays with constructs containing different alleles of MDM4 3’-UTR region in SCLC H446 cells.

H446 cells were cotransfected with pRL-SV40 to standardize transfection efficiency. Fold increase was measured by defining the activity of cells co-transfected with both pGL3-rs4245739A or pGL3-rs4245739Creporter construct and NC-RNAs as 1. All experiments were performed in triplicates at least in three independent transfection experiments and each value represents mean ± SD. *P<0.05compared with each of the luciferase construct by t-tests. NC-RNA, negative control RNAs; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the association between the MDM4 rs4245739 functional SNP and SCLC risk via a case-control approach. We observed that individuals with MDM4 rs4245739 AC or CC genotypes show significantly decreased SCLC risk compared with the AA genotype carriers. To reveal miR-191-5p/miR-887-3p mediated allelic-regulation by this SNP, we examined luciferase activities in SCLC cells transfected with different allelic reporter constructs. The genotype-phenotype correlation analyses indicated that both miRNAs could inhibit MDM4 expression only in SCLC cells with C-allele constructs expression but not A-allele constructs. These results highlight the involvement of functional genetic variants in miRNA-binding sites in SCLC etiology.

Accumulated evidences demonstrated that genetic makeup might have direct contribution of to SCLC risk [33–35]. Interestingly, referring to the databases of gene expression profile to identify genes that are deregulated in SCLC and their SNPs in the 3’-UTR, Xiong et al identified a SCLC susceptibility SNP rs3134615 G>T can inhibit the interaction of miR-1827 with MYCL1 3’-UTR, resulting in higher constitutive expression of MYCL1 [35]. Consistent with this notion, we also found a MDM43’-UTR SNP targeted by miRNAs is associated with SCLC susceptibility.

The MDM4rs4245739 polymorphism showed a consistent association with SCLC risk intwo independent case-control sets, which are unlikely to be attributable to unknown confounding factors due to having significantly increased odd ratios with small P values. In addition, the genotype-phenotype relationship between the rs4245739 polymorphism and reporter gene expression supports our conclusion. Moreover, the MDM4rs4245739 SNP might be a common genetic risk component for different cancers, which has been proved by our group and others via either candidate gene approach or GWAS [19–26]. For example,we previously found that rs4245739 AC and CC genotypes were significantly associated with decreased risk of esophageal cancer [22], a malignancy with similar environmental etiology of SCLC (i.e. heavy smoking). However, there might be several limitations in the current case-control study. For instance, since all SCLC cases were recruited from the hospital, inherent selection bias may exist. Therefore, the findings of our study warrant to be validated in a population-based prospective study in the future. Relatively small sample size for non-smokers should be further analyzed in a larger population.

In summary, our results suggested that functional MDM4 rs4245739 SNP was associated with a significantly decreased SCLC risk in Chinese Han populations. The associations between SNPs and SCLC risk are remarkable in nonsmokers. Given this fact, further efforts are needed to examine whether MDM4 rs4245739 genetic polymorphism can be used as a potential diagnostic marker of SCLC.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 31271382 & 81201586; URL: http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/); the National High-Tech Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers: 2015AA020950; URL: http://www.most.gov.cn/); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant numbers: YS1407; URL: http://www.moe.edu.cn/); Beijing Higher Education Young Elite Teacher Project (grant numbers: YETP0521; URL: http://www.bjedu.gov.cn/); and Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (grant numbers: IRT13045; URL: http://www.moe.edu.cn/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. (2009) Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 59:225–249. 10.3322/caac.20006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jackman DM, Johnson BE. (2005) Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 366:1385–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simon GR, Wagner H, American College of Chest Physicians (2003) Small cell lung cancer. Chest. 123:259S–271S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, et al. (2008)Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet 40:616–22. 10.1038/ng.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, Zaridze D, et al. (2008) A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature 452:633–637. 10.1038/nature06885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, et al. (2008) A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452:638–642. 10.1038/nature06846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Y, Broderick P, Webb E, Wu X, Vijayakrishnan J, Matakidou A, et al. (2008) Common 5p15.33 and 6p21.33 variants influence lung cancer risk. Nat Genet 40:1407–1409. 10.1038/ng.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McKay JD, Hung RJ, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Chabrier A, Byrnes G, et al. (2008) Lung cancer susceptibility locus at 5p15.33. Nat Genet 40:1404–1406. 10.1038/ng.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y, McKay JD, Rafnar T, Wang Z, Timofeeva MN, Broderick P, et al. (2014)Rare variants of large effect in BRCA2 and CHEK2 affect risk of lung cancer. Nat Genet 46:736–741. 10.1038/ng.3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lan Q, Hsiung CA, Matsuo K, Hong YC, Seow A, Wang Z, et al. (2012) Genome-wide association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci in never-smoking women in Asia. Nat Genet 44:1330–1335. 10.1038/ng.2456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong J, Hu Z, Wu C, Guo H, Zhou B, Lv J, et al. (2012) Association analyses identify multiple new lung cancer susceptibility loci and their interactions with smoking in the Chinese population. Nat Genet 44:895–899. 10.1038/ng.2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu Z, Wu C, Shi Y, Guo H, Zhao X, Yin Z, et al. (2011) A genome-wide association study identifies two new lung cancer susceptibility loci at 13q12.12 and 22q12.2 in Han Chinese. Nat Genet 43:792–796. 10.1038/ng.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shvarts A, Steegenga WT, Riteco N, van Laar T, Dekker P, Bazuine M, et al. (1996) MDMX: a novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J 15:5349–5357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wade M, Wang YV, Wahl GM. (2010) The p53 orchestra: Mdm2 and Mdmx set the tone. Trends Cell Biol 20:299–309. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kadakia M, Brown TL, McGorry MM, Berberich SJ. (2002) MdmX inhibits Smad transactivation. Oncogene 21:8776–8785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jin Y, Zeng SX, Sun XX, Lee H, Blattner C, Xiao Z, et al. (2008) MDMX promotes proteasomal turnover of p21 at G1 and early S phases independently of, but in cooperation with, MDM2. Mol Cell Biol 28:1218–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller KR, Kelley K, Tuttle R, Berberich SJ. (2010) HdmX overexpression inhibits oncogene induced cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 9:3376–3382. 10.4161/cc.9.16.12779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiong S, Pant V, Suh YA, Van Pelt CS, Wang Y, Valentin-Vega YA, et al. (2010) Spontaneous tumorigenesis in mice overexpressing the p53-negative regulator Mdm4. Cancer Res 70:7148–7154. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wynendaele J, Böhnke A, Leucci E, Nielsen SJ, Lambertz I, Hammer S, et al. (2010) An illegitimate microRNA target site within the 3' UTR of MDM4 affects ovarian cancer progression and chemosensitivity. Cancer Res 70:9641–9649. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stegeman S, Moya L, Selth LA, Spurdle AB, Clements J, Batra J. (2015) A genetic variant of MDM4 influences regulation by multiple microRNAs in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 22:265–276. 10.1530/ERC-15-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McEvoy J, Ulyanov A, Brennan R, Wu G, Pounds S, Zhang J, et al. (2012) Analysis of MDM2 and MDM4 single nucleotide polymorphisms, mRNA splicing and protein expression in retinoblastoma. PLoS One 7:e42739 10.1371/journal.pone.0042739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou L, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhou C, Li M, Tang X, et al. (2013) Association of a genetic variation in a miR-191 binding site in MDM4 with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 8:e64331 10.1371/journal.pone.0064331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eeles RA, Olama AA, Benlloch S, Saunders EJ, Leongamornlert DA, Tymrakiewicz M, et al. (2013) Identification of 23 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci using the iCOGS custom genotyping array. Nat Genet 45:385–391. 10.1038/ng.2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia-Closas M, Couch FJ, Lindstrom S, Michailidou K, Schmidt MK, Brook MN, et al. (2013) Genome-wide association studies identify four ER negative-specific breast cancer risk loci. Nat Genet 45:392–498. 10.1038/ng.2561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu J, Tang X, Li M, Lu C, Shi J, Zhou L, et al. (2013) Functional MDM4 rs4245739 genetic variant, alone and in combination with P53 Arg72Pro polymorphism, contributes to breast cancer susceptibility. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140:151–157. 10.1007/s10549-013-2615-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fan C, Wei J, Yuan C, Wang X, Jiang C, Zhou C, et al. (2014) The functional TP53 rs1042522 and MDM4 rs4245739 genetic variants contribute to Non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk. PLoS One 9:e107047 10.1371/journal.pone.0107047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang X, Zhou L, Fu G, Sun F, Shi J, Wei J, et al. (2014) The identification of an ESCC susceptibility SNP rs920778 that regulates the expression of lncRNA HOTAIR via a novel intronic enhancer. Carcinogenesis 35:2062–2067. 10.1093/carcin/bgu103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang X, Wei J, Zhou L, Zhou C, Shi J, Yuan Q, et al. (2013) A functional BRCA1 coding sequence genetic variant contributes to risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 34:2309–2313. 10.1093/carcin/bgt213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X, Li M, Wang Z, Han S, Tang X, Ge Y, et al. (2015) Silencing of Long Noncoding RNA MALAT1 by miR-101 and miR-217 Inhibits Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. J Biol Chem 290:3925–3935. 10.1074/jbc.M114.596866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu C, Hu Z, Yu D, Huang L, Jin G, Liang J, et al. (2009) Genetic variants on chromosome 15q25 associated with lung cancer risk in Chinese populations. Cancer Res 69:5065–5072. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shi J, Sun F, Peng L, Li B, Liu L, Zhou C, et al. (2013) Leukocyte telomere length-related genetic variants in 1p34.2 and 14q21 loci contribute to the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 132:2799–2807. 10.1002/ijc.27959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang M, Sun T, Zhou Y, Wang L, Liu L, Zhang X, et al. (2012) The functional cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated Protein 4 49G-to-A genetic variant and risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer 118:4681–4686. 10.1002/cncr.27455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dally H, Edler L, Jäger B, Schmezer P, Spiegelhalder B, Dienemann H, et al. (2003) The CYP3A4*1B allele increases risk for small cell lung cancer: effect of gender and smoking dose. Pharmacogenetics 13:607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dally H, Gassner K, Jäger B, Schmezer P, Spiegelhalder B, Edler L, et al. (2002) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) genotype and lung cancer histologic types: the MPO -463 A allele is associated with reduced risk for small cell lung cancer in smokers. Int J Cancer 102:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xiong F, Wu C, Chang J, Yu D, Xu B, Yuan P, et al. (2011) Genetic variation in an miRNA-1827 binding site in MYCL1 alters susceptibility to small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 71:5175–5181. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.