Abstract

Hispanic/Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States are disproportionately affected by HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs); however, no efficacious behavioral interventions are currently available for use with this vulnerable population. We describe the development and enhancement of HOLA en Grupos, a community-based behavioral HIV/STD prevention intervention for Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latino MSM that is currently being implemented and evaluated. Our enhancement process included incorporating local data on risks and context; identifying community priorities; defining intervention core elements and key characteristics; developing a logic model; developing an intervention logo; enhancing intervention activities and materials; scripting intervention delivery; expanding the comparison intervention; and establishing a materials review committee. If efficacious, HOLA en Grupos will be the first behavioral intervention to be identified for potential use with Hispanic/Latino MSM, thereby contributing to the body of evidence-based resources that may be used for preventing HIV/STD infection among these MSM and their sex partners.

Hispanics/Latinos in the United States (US) are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and have been identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a population at great risk for HIV infection (CDC, 2011a). Hispanics/Latinos have the second highest rate of AIDS diagnoses of all racial and ethnic groups, accounting for nearly 20% of the total number of new AIDS cases reported each year; this is three times the rate of new cases among non-Hispanic/Latino whites (CDC, 2013). Rates of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are two to four times as high among Hispanics/Latinos as among non-Hispanic/Latino whites (CDC, 2014; Southern AIDS Coalition, 2012). Many southeastern states, including North Carolina (NC), consistently lead the nation in reported cases of AIDS, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis (CDC, 2014; Southern AIDS Coalition, 2012). HIV incidence rates in NC are 40% higher than the national rate, and HIV and STD infection rates among Hispanics/Latinos in the state are three and four times that of non-Hispanic/Latino whites (NC Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

Men of all races and ethnicities who have sex with men (MSM) also continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV, and the number of new infections among MSM continues to increase, with a steeper increase among the youngest MSM. Moreover, Hispanic/Latino MSM have twice the rate of HIV infection of non-Hispanic/Latino white MSM, and the majority of new infections are found in a younger age group of Hispanics/Latinos compared to non-Hispanic/Latino whites (CDC, 2013).

At the same time, the proportion of the US population that identifies as Hispanic/Latino has grown considerably during the past two decades. Between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, the Hispanic/Latino population in the US grew by 43%. In NC, the number of Hispanics/Latinos grew by 111%, giving NC one of the fastest-growing Hispanic/Latino populations in the US (US Census Bureau, 2014). Much of this new growth has occurred in rural communities (Southern AIDS Coalition, 2012). Jobs in farm work, construction, and factories, coupled with dissatisfaction with the quality of life in traditional Hispanic/Latino destinations in the US, have led many immigrants to leave higher-density Hispanic/Latino destinations and relocate to the Southeast, and NC in particular (Painter, 2008; Rhodes et al., 2007). However, Hispanic/Latino immigrants are increasingly coming to the Southeast directly from their countries of origin, bypassing traditional Hispanic/Latino destinations (Massey & Capoferro, 2008). Compared to Hispanics/Latinos in states that have a history of Hispanic/Latino immigration (e.g., Arizona, California, Florida, New York, and Texas), immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in NC resemble those in the Southeast more generally; they tend to be younger and disproportionately male, come from rural communities in southern Mexico and Central America, have lower educational attainment, and settle in communities without histories of immigration. These communities also lack developed infrastructures to meet their needs (Kissinger et al., 2012; Kochhar, Suro, & Tafoya, 2005; Painter, 2008; Rhodes, 2012).

Despite the rapid growth of Hispanic/Latino populations in the US and the disproportionate burden of HIV and STDs among Hispanic/Latino MSM (CDC, 2013, 2014), no efficacious behavioral HIV/STD-prevention interventions have been identified and listed in the Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/index.html) for potential use with this vulnerable population. Thus, there is a profound need for efficacious HIV prevention interventions for use with Hispanic/Latino MSM (Carballo-Dieguez et al., 2005; Herbst, Beeker, et al., 2007).

In this paper, we describe the development and enhancement of a community-based behavioral HIV/STD prevention intervention for Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latino MSM that is currently being implemented and evaluated with support from the CDC. Throughout the intervention development, implementation, and evaluation processes, community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles have been applied. This paper provides an example of how representatives from universities, government, and non-governmental institutions and community-based organizations can convene and build on one another’s experiences and strengths to develop, enhance, and rigorously evaluate a behavioral prevention intervention.

METHODS

Community-based Participatory Research

CBPR is a collaborative research approach designed to ensure authentic participation by communities (including those community members affected by the issues being studied); representatives of community-based organizations (CBOs), health departments, and local businesses; and scientists from universities, government, or other types of research organizations in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through action, including intervention development, implementation, and evaluation. CBPR emphasizes co-learning; reciprocal transfer of expertise; sharing of decision-making power; and mutual ownership of the processes and products of research (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Daniel, & Aronson, 2013; Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010).

Our CBPR partnership has been working to better understand and develop interventions to meet the needs of the immigrant Latino community in NC for more than a decade (Rhodes et al., 2014). Partners recognize that complex health problems, particularly HIV and STDs, may be ill-suited for traditional “outside-expert” approaches to research that may result in interventions having limited effectiveness (Green, 2001; Institute of Medicine, 2000; Israel et al., 2005; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes, Malow, et al., 2010). Our partnership brings together community members from the Hispanic/Latino and MSM communities and representatives from organizations (including AIDS service and Hispanic/Latino-serving organizations and health departments), the scientific and medical sectors, and other relevant agencies to nurture long-term health improvement through sustained teamwork.

Phases in the Development of an Evidence-Based Intervention for Latino Sexual Minorities

Latino gay men step forward to ask for programming

During the early stages of implementing HoMBReS, a community-level HIV prevention intervention developed in 2004 and designed to increase condom use and HIV and STD testing by predominately heterosexual Hispanic/Latino men who were members of soccer team-based social networks (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, Leichliter, & Montano, 2009; Rhodes et al., 2006), a group of Hispanic/Latino MSM, who had learned of the intervention, stepped forward and asked members of the CBPR partnership what the partnership and its individual organizational members could offer to MSM in terms of HIV-prevention programming. Partners began early discussions with these men and their informal networks. After several months of ongoing discussions between partnership members and a total of 30 Hispanic/Latino MSM from rural communities in NC, several Hispanic/Latino MSM joined the CBPR partnership and participated in two parallel processes. One process was to conduct formative research to better understand the prevention priorities and sexual health needs of Hispanic/Latino MSM in rural NC (Gilbert & Rhodes, 2013a, 2013b; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2010; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Martinez, et al., 2013; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2012); the other was to expedite the development of an intervention for these populations. As a participant in the CBPR partnership noted, “As a gay Latino, I want something [to prevent HIV] for me and friends, including those I might have sex with, sooner as opposed to later.”

Iteratively building on existing resources and expanding partnership capacities

Thus, a small group of representatives from the partnership worked iteratively to develop an HIV-prevention intervention for Hispanic/Latino MSM. Development was based on a review of existing interventions that targeted Hispanic/Latino sexual minorities specifically, including Hermanos de Luna y Sol (http://cci.sfsu.edu/taxonomy/term/37), and the experiences with other interventions that the CBPR partnership had developed for the Hispanic/Latino community, including HoMBReS (Rhodes et al., 2009; Rhodes et al., 2006) and Proyecto PUEDES (Promotoras Unidas Educando de la Sexualidad), a sexual and reproductive health intervention for Hispanic/Latina women (Rhodes, Kelley, et al., 2012). An academic partner (the first author) provided guidance over time on health behavior theory and what the literature suggested were effective and ineffective approaches for increasing condom use and HIV and STD testing. This process, which lasted approximately six months, led to the development a Spanish-language intervention known as Hombres Ofreciendo Liderazgo y Apoyo en Grupos (Hello: Men Offering Leadership and Support in Groups; HOLA en Grupos), which was designed to increase condom use and HIV testing among Hispanic/Latino MSM.

At the same time that the intervention was being developed, a need to increase understanding about sexual diversity and to build capacity to provide culturally congruent services for sexual and gender minorities, including MSM and transgender persons, was identified within the CBPR partnership. Partnership members realized that to support Hispanic/Latino MSM, some CBPR members needed help to overcome their prejudices about Hispanic/Latino MSM; for example, some staff from a Latino-serving partner CBO did not want Hispanic/Latino MSM in their offices. Recognizing the role of these prejudices and subsequent discrimination on health behavior, the CBO’s executive director initiated sensitivity training focused on LGBT health issues for staff. CBPR partners supported this effort. For example, an academic partner shared what is currently known about gay and bisexual identity and MSM behavior as well as behavioral and social determinants of HIV and STD exposure and transmission. Hispanic/Latino gay men who were “out” about their orientation described their lived experiences to give a face to the LGBT community. Finally, the executive director of the CBO reviewed the mission and values of the organization with staff to reaffirm expectations. This was a necessary step in order to move forward with implementation of an intervention for Hispanic/Latino MSM.

Ongoing quality improvement

HOLA en Grupos was implemented during four sessions, usually over two weeks, by a trained Hispanic/Latino gay man over a two-year period to more than 80 Hispanic/Latino MSM as part of the ongoing community-based programming of a local AIDS service organization. Retention rates were high, with 93% of participants attending all four sessions. Feedback from participants was positive, and they recommended the intervention to their friends. Furthermore, persons who were involved with implementing the intervention were convinced that it positively influenced behavior and promoted the sexual health of Hispanic/Latino MSM. However, the intervention remained a community-based effort, and it was not tested to determine whether it actually increased condom use or HIV testing by participants. During the period of intervention delivery, participants also provided recommendations for improvements. For example, they recommended that the intervention include less didactic learning. To address this, intervention implementation staff suggested that DVD segments and vignettes could be useful to serve as triggers for discussion. However, after reviewing available DVD and video segments and vignettes, including some available free on YouTube, the partnership determined that none met the needs and priorities of Hispanic/Latino MSM in the area. The context and experiences of Hispanics/Latinos in NC and the South differ somewhat from those living in states with a longer history of Hispanic/Latino presence or in HIV epicenters with histories of HIV prevention, care, research, and programming (e.g., Chicago, New York City, and San Francisco). Thus, the partners decided to use DVD segments and vignettes from HoMBReS-2, a small-group intervention based on the earlier community-level, social-network based HoMBReS intervention, also developed by our partnership to increase condom use and HIV testing among predominately heterosexual Latino men in rural NC (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011). Three segments and vignettes were subsequently incorporated into HOLA en Grupos. The first segment summarized the impacts of HIV and STDs on Hispanic/Latino communities to raise consciousness; the second vignette described how to get tested for HIV and STDs in a public health department to de-mystify the process, role model strategies to overcome challenges that Hispanic/Latino MSM face in accessing health department services (e.g., limited interpretation services), and build self-efficacy related to overcoming challenges. The third vignette presented the pros-and-cons of using condoms often heard in the local community, using a Hispanic/Latino man with an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other.

CDC support for evaluating locally developed HIV/STD prevention interventions

In an effort to learn from community-based HIV/STD prevention practices and make effective practices available for HIV/STD prevention more broadly, CDC initiated the Innovative Interventions Project in 2004 (CDC, 2004). The project identified and supported rigorous evaluations of culturally appropriate HIV prevention interventions that CBOs had developed and were delivering to minority populations at high risk for HIV infection in their communities, and that had shown some promise of being effective, but had not been rigorously evaluated because of funding constraints.

Competitively selected CBOs were funded by CDC to evaluate their interventions and, if the CBOs lacked sufficient internal capacity to evaluate their interventions on their own, in collaboration with university-based researchers. The CDC approach required all CBO evaluations to satisfy criteria for evaluation design and strength of evidence concerning evaluation outcomes to potentially qualify for inclusion in the Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/index.html), and for possible packaging through CDC’s Replicating Effective Interventions Plus project (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/rep/packages) and dissemination for use by service provider organizations through CDC’s Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions program (http://www.effectiveinterventions.org; Collins & Tomlinson, 2014). The Innovative Interventions Project funded People of Color in Crisis to evaluate the small-group Many Men, Many Voices (3MV) intervention, which the CBO had co-developed for and had been delivering to black MSM in the New York area since 1997 (Wilton et al., 2009); SisterLove, Inc. to evaluate the small-group Healthy Love Workshop intervention for heterosexual black women that it developed and had been delivering to women in metropolitan Atlanta since 1989 (Diallo et al., 2010); and the Philadelphia Health Management Corporation to evaluate the theater-based Preventing AIDS through Live Movement and Sound (PALMS) intervention for incarcerated and adjudicated minority adolescent males that it had developed and had been delivering to these populations since 1993 (Lauby et al., 2010). Based on the evaluation results and the rigor of the evaluation design, all of the CBO interventions satisfied CDC’s criteria for classification as evidence-based interventions. 3MV was included in the CDC Compendium as a “best evidence” intervention. The intervention was included in CDC’s Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions project, and revised intervention materials were distributed to CDC-funded CBOs and health departments to support delivery of the intervention and made available to the public (www.effectiveinterventions.org; Collins & Tomlinson, 2014; Herbst, Painter, Tomlinson, & Alvarez, 2014). The Healthy Love workshop was listed as a “good evidence” intervention in the Compendium, and with CDC support, was packaged and is also available (http://www.effectiveinterventions.org) for use by service providers. The PALMS intervention was classified by CDC as a “good evidence” intervention and added to the Compendium. The CDC Innovative Interventions project demonstrated that CBOs could develop and deliver effective HIV prevention interventions for at-risk minority populations and, with support from CDC and researcher partners, rigorously evaluate their locally-developed interventions (Painter, Ngalame, Lucas, Lauby, & Herbst, 2010).

In 2010, CDC implemented the follow-on Homegrown Interventions project (CDC, 2009), to continue the process of identifying and supporting rigorous evaluations of behavioral HIV/STD prevention interventions developed by CBOs. Because of the persistent, disproportionate impacts of HIV/AIDS on racial/ethnic minority MSM, the Homegrown project focuses on interventions designed specifically for black and Hispanic/Latino MSM. Our CBPR partnership was awarded CDC funding to enhance, implement, and evaluate HOLA en Grupos. Implementation and evaluation of the intervention are ongoing. During this process, we partnered with some of the same CDC behavioral scientists who had participated in CBO evaluations during the Innovative Interventions project. The Homegrown project is also funding the Los Angeles County Office of AIDS Programs and Policy and the In the Meantime Men’s Group, Inc., to evaluate MyLife MyStyle for young black MSM in Los Angeles, California, and Loyola University and the Black Men’s Xchange to evaluate the Critical Thinking and Cultural Affirmation intervention for black MSM in Chicago, Illinois.

Enhancement of HOLA en Grupos

Because HOLA en Grupos was developed with limited resources and partnership members know that the context in which Hispanics/Latinos live changes rapidly, particularly in light of rapid immigration and the changing demographics in the South, our partnership chose to enhance the intervention before rigorously evaluating it. Enhancement entailed several steps, including incorporating recently collected data that reflected the local community, identifying and refining intervention priorities, defining core elements and key characteristics, developing a logic model, developing an intervention logo, improving existing and developing new activities and materials; scripting intervention delivery; expanding the comparison intervention; and establishing a materials review committee.

Incorporating local data

As a response to the first group of Latino gay men from our local area who had stepped forward to express a need for culturally congruent interventions for their community, our CBPR partnership had initiated new research using both qualitative and quantitative methods designed to better understand the lived experiences of Hispanic/Latino MSM, risks to their sexual health and the contexts of risk, and prevention needs and priorities. We reviewed and incorporated findings from this research to ensure the intervention was as relevant to local community priorities and sexual health needs as possible. Members of our CBPR partnership were involved throughout the collection, analysis, and interpretation of these local data (Gilbert & Rhodes, 2013a, 2013b; Rhodes, 2012; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Downs, & Aronson, 2013; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2010; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Martinez, et al., 2013; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2012), and together we reviewed findings from multiple studies as a group during numerous sessions to establish common understandings and identify priorities.

Identifying and refining needs and priorities

The needs and priorities of Hispanic/Latino MSM that emerged through the incorporation of local data included: (a) increasing awareness of the magnitude of HIV and STD infection; (b) providing information on HIV and STDs, modes of transmission, signs, symptoms, and prevention strategies (including condom use and abstinence); (c) offering guidance on local counseling, testing, care, and treatment services, eligibility requirements, and “what to expect” when accessing and utilizing services; (d) building condom use skills (e.g., how to communicate effectively, how to properly select, use, and dispose of condoms); (e) changing health-compromising norms of what it means to be an immigrant, a Latino man, a gay man, an MSM, and/or a transgender person; and (f) building supportive relationships and sense of community.

Defining intervention core elements and key characteristics

One of the first activities with CDC partners during the enhancement process was the identification of core elements and key characteristics. We identified the intervention’s core elements – those components that are essential to its effectiveness and that must not be altered – and key characteristics, intervention features (e.g., activities and delivery methods) that can be modified without negatively affecting intervention effectiveness (Galbraith et al., 2011; McKleroy et al., 2006). This process helped our partnership to think critically about what was needed to produce the desired intervention outcomes. It also contributed to development of the logic model; implementation strategies, such as didactic teaching, DVD discussion triggers, and role plays to practice communication and behaviors; specific intervention activities; and implementation processes (e.g., who could implement the intervention and number and timing of sessions). Defining the core elements was an iterative process that included small group discussions with CDC partners and presentation to and feedback from members of the larger CBPR partnership. This process included examining the core elements from other behavioral HIV prevention interventions, exploring the theories underlying HOLA en Grupos, and articulating the partnership’s intuitive understanding of what made the intervention work (in the absence of efficacy data). The core elements and key characteristics of HOLA en Grupos are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Core elements and key characteristics

| Core elements |

|

| Key characteristics |

|

Developing a logic model

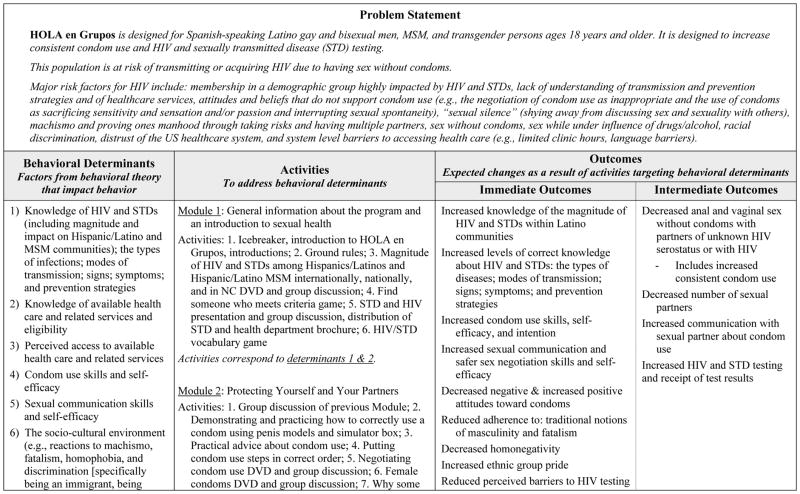

Another activity in which CDC partners were particularly involved was the development of an intervention logic model. This process allowed members of our partnership to work with CDC to visually depict the links among behavioral determinants of HIV and STD risk as identified in both the literature and our local research, intervention activities designed to address behavioral determinants, and immediate and intermediate outcomes. The development of the logic model facilitated a process for members of the partnership to discuss their assumptions and engage in a process of blending perspectives, insights, and experiences. During these discussions, community members described their real-world experiences and perspectives on risk and the context of risk among Hispanic/Latino MSM like themselves and what might and might not work to influence behavioral determinants. Service providers, including representatives from CBOs, provided insights based on their experience over the years of providing HIV- and non-HIV-related services to Hispanics/Latinos, and academic researchers were able to synthesize the literature and provide expertise in health behavior theory and community health promotion. The CDC partners provided guidance based on their experiences of collaborating with CBOs and researchers during the Innovative Interventions project.

During development of the logic model, variables were identified for measurement; these included mediating and moderating variables and sexual behaviors. Behavioral outcomes of primary interest included increased condom use during anal and vaginal sex with partners of HIV-positive or unknown HIV serostatus; decreased number of sexual partners; increased communication with sexual partners about condom use; and increased HIV and STD testing and receipt of test results. Figure 1 provides an abbreviated version of the HOLA en Grupos behavior change logic model.

Figure 1.

HOLA en Grupos behavior change logic model

Developing an intervention logo

The original HOLA en Grupos intervention did not have a logo; however, our partnership had learned that having a recognizable logo to brand the intervention was key to community recruitment, participation, and retention in our other research projects. Thus, we developed a logo by consulting with a group of Hispanic/Latino MSM, HOLA en Grupos project coordinators, and the Wake Forest Office of Creative Communications (OCC). The partners met with OCC staff to discuss logo concepts, and OCC staff presented sketches to the group for feedback. Discussion about the logos and color schemes were iterative; after agreement on a few prototype logos with color options, the logos were presented to the entire CBPR partnership, along with other Hispanic/Latino MSM who were not part of the partnership. The final intervention logo is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The HOLA en Grupos logo

The logo includes a sun, which is an important symbol in the countries of origin of many Hispanics/Latinos. Before arrival of the Spaniards, many of those living in diverse areas of Latin America worshipped the sun, which they believed was the most powerful star of the cosmos and had profound influence on society. For the Aztecs, the sun image signified the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli, the giver of life and the guardian of the heavens. In fact, some Aztecs referred to themselves as “people of the sun”. The sun was also highly regarded by the Mayan civilization; they believed that the sun brought about high yielding crops. The Incan Empire considered the sun to be their patron deity. Although the significance of the sun has changed in modern times, the importance of the sun’s mythology and its image remain (Williamson, 2010).

The logo includes two other key elements within the sun. There is an image of the stone rings that are used when playing the Mesoamerican ball game known by many names including ōllamaliztli, pitz, tlachtli, and ullamaliztli. Played by two opposing teams of two to four players, the goal of the ballgame was to pass a rubber ball among one’s teammates using elbows, knees, hips and head without touching it with one’s hands and then get the ball to pass through one of the rings that hung high along the walls on either side of the ball court. The ball game was a key component of Mesoamerican culture, and the ball court remains a common and distinguishing feature in archaeological excavations throughout the region (Gillespie, 1991). Finally, within the lines representing the stone rings, is the subtle shape of a rolled condom.

Enhancing existing and developing new activities and materials

We continued our highly participatory approach to enhance HOLA en Grupos. Besides the ongoing meetings of CBPR partners to enhance the intervention and ongoing efforts by project coordinators to translate ideas and concepts into enhanced and new activities and materials, we reviewed proposed activities and materials with community members who were not originally part of the CBPR partnership to obtain their feedback. This approach of seeking input from new community members at different stages of the enhancement process was important because our partnership learned early on that with time, some CBPR community members may not reflect their communities’ views in the same way as they did at the beginning of the partnership. They become socialized to the priorities of the research study, develop loyalties to the partnership, and/or partnership organizations and may no longer represent the perspectives of the community. Thus, during the enhancement process, it was important to continually engage members of the community who were not familiar with research and did not have allegiances to the partnership and partnership organizations or to the way in which research is often conducted. Their perspectives can be highly insightful.

The development of a wallet-sized “condom tips” card with information on correct condom use for intervention participants illustrates the process of “going back to the community” for iterative feedback and validation of decisions during the enhancement process. The original condom tips card was developed for the HoMBReS-2 intervention for predominately heterosexual Hispanic/Latino men (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011). We revised the card to include issues that Hispanic/Latino MSM minorities identified as important, including a rough drawing of the silhouettes of two men getting ready to have anal sex. After a prototype was developed, the executive director from a CBO member of the partnership expressed concern that the drawing was too explicit. She was concerned that if a child found the card, her organization could be subject to serious criticism. The partnership debated the issue, and most members wanted to maintain the drawing. However, our partnership rarely uses democratic approaches to decision-making and instead, relies on consensus (Rhodes, 2012). Despite ongoing discussion, the executive director’s concerns about the card were not assuaged. The issue eventually became fractious, and during one session when the issue was debated, several Hispanic/Latino MSM who worked for the executive director decided that the drawings should be changed, understandably following their director’s lead. Given this impasse, members of the partnership agreed to convene a group of Hispanic/Latino MSM in the community who reflected those for whom the intervention was designed, to gather their impressions. They were enthusiastic about the original drawing. A participant noted, “This is clearly for me; usually these types of materials are made for general audiences, but this speaks to me.” In light of this feedback, the partnership decided to use the original drawing.

We also developed scripts for new DVD segments and vignettes. We added MSM-specific HIV data to the consciousness-raising vignette originally used for the HoMBReS-2 intervention (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011), and designed to reinforce the introduction to the intervention provided by the interventionist. We developed a second vignette in which a Hispanic/Latino MSM goes to a club where he meets another man; they later go home together and negotiate condom use prior to having sex. One of them does not want to use condoms and expresses many of the misconceptions reported by local Hispanic/Latino MSM; e.g., insertive anal sex partners cannot get any type of infection; looking healthy means one is uninfected; withdrawing before ejaculation is safe; and condoms break too easily so are not worth the effort. The other MSM responds in a non-confrontational manner, explains why the reasons given for not using condoms could lead to HIV and STD transmission, and they conclude by agreeing to use condoms (Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2010; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2012).

We learned from prior research that Hispanic/Latinos wanted to hear from other Hispanics/Latinos who are living with HIV (Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011). Although some partners preferred to have an HIV-positive Hispanic/Latino MSM share his story in person, we decided that this was not feasible for two reasons: 1) we would not be able to standardize such an activity over multiple sessions during intervention delivery or, if found efficacious, in subsequent dissemination; and 2) we could not ensure the confidentiality and safety of an HIV-positive Hispanic/Latino MSM who disclosed his status publically. Thus, we worked with the HIV clinic at Wake Forest School of Medicine to recruit a young Hispanic/Latino MSM with HIV to share his story on videotape. Our partnership crafted a variety of questions or prompts that he answered, and a CBPR partner who owns a video production company shot the film and worked with other partners to edit the segment to 14 minutes. The MSM’s identity was obscured and his voice was slightly altered to protect his identity; however, despite his not being recognizable, he mentions places and contexts that are familiar to some participants. He shares his story about mixing alcohol, drugs, and sex; having multiple partners; and assuming that married men or good-looking men are free from HIV. He also discusses his experiences with HIV and STD testing and finding out he was infected, and shares his experiences with family, obtaining medical care, etc.

Scripting intervention delivery

Finally, we further developed the intervention script. Partnership members wanted to have the entire script of what an interventionist should say during each step of intervention delivery. Although we knew that an interventionist may put intervention activities into his own words, we wanted the interventionist to have comprehensive script he could use should he become distracted or confused about the message.

Overall, the enhancement process took about eight months. Although the original intervention had been promising according to staff from the CBO who had been implementing it, our partnership knew that the opportunity to enhance the intervention using authentic approaches to CBPR in partnership with CDC was unique. We wanted to ensure that the intervention materials and delivery methods were as meaningful as possible to the community for which it was designed; that it was updated with locally collected data and based on the current state-of-the-science; and it was standardized to ensure consistent delivery during the efficacy study that is ongoing.

Expanding the comparison intervention

Originally, we had planned to use a single-session cancer prevention intervention that we had adapted and used previously as our comparison intervention during the efficacy trial for the HoMBReS-2 intervention (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011). However, we realized that we had to extend the comparison intervention from one to four sessions to ensure that participants in the comparison intervention received similar amounts of attention from interventionists as participants in the four-session HOLA en Grupos. Thus, the comparison intervention was expanded to four sessions to include educational programming on cholesterol and hypertension; diabetes; prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer; and alcohol use and abuse. These topics were selected based on community and partnership feedback. Partners also developed the comparison intervention to be somewhat more interactive and engaging than the single session version with video segments on health topics used as triggers for discussion and supplemental materials (e.g., brochures).

Establishing materials review committee

We also established a materials review committee of community members who are not part of the intervention study to determine the appropriateness of written materials, audiovisual materials, and pictorials for the intended audience (i.e., Hispanic/Latino MSM). For example, this committee was also able to balance the concerns of the CBO executive director who did not want the condom tips card sketches to be recognizable as two men with what would resonate and be meaningful for the community of MSM that would participate in the intervention.

RESULTS

The enhanced intervention maintains the interactive and activity-based format of the original intervention, was developed and is delivered in Spanish, and continues to address the needs and priorities of Hispanic/Latino MSM. It blends the lived experiences of Hispanic/Latino MSM, the experiences of organizational representatives based in ongoing program and service provision; and sound science (including empowerment; Freire, 1973; and social cognitive theories Bandura, 1986). Like the original intervention, the enhanced HOLA en Grupos intervention includes four modules; the modules and the corresponding activities are outlined in the Activities column in Figure 1.

Module 1 provides general information about the purpose of the intervention and an introduction to sexual health, including prevalence and incidence of HIV and STDs among Hispanic/Latino and Hispanic/Latino MSM internationally, nationally, and finally in NC to raise participants’ consciousness about the burden of HIV and STDs; information about HIV, STDs, and healthcare services to lay the foundation on which prevention learning can be placed; and an opportunity to build shared understanding among participants through learning HIV and STD-related vocabulary.

Module 2 includes multiple activities designed to provide guidance on how to protect oneself and one’s partners through learning and practicing new skills, including negotiation and use of condoms. This module concludes with a homework activity that we developed in partnership with researchers at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University. Participants are given different brands and types of condoms, including six male condoms and one female condom, and asked to open the packages and study the condoms on their own. One of the male condoms is the brand available without cost in local health departments. The idea of the homework is not necessarily to have sex with the condoms, but to give participants an opportunity to compare condoms (e.g., textures, thickness, and shapes) on their own. They are encouraged to decide which type of condom they prefer; experimenting with different types of condoms, participants may decide that free condoms available in health departments are just as preferable as other types, or they may conclude that one brand is worth the price in a pharmacy.

Because some participants may choose to use female condoms with male partners, we included guidance on the use of female condoms during this module. Research suggests that the female condom may not be widely used by MSM (Kelvin et al., 2011). This may be because, they are not approved for anal intercourse (Mantell et al., 2009), which results in practitioners and providers (including health educators) not promoting them widely. Nevertheless, because our partnership believed that some participants may use female condoms, we determined that it was important for participants to have all the facts about their sexual health options, and that discussion of female condom use in the module affirmed our commitment to social justice.

Module 3 includes activities designed to explore the Hispanic/Latino culture and how cultural values and social context affect sexual health. Reciprocal determinism, which suggests that an individual, his or her behavior, and the environment influence one another (Bandura, 1986), is introduced and used to illustrate how Hispanic/Latino cultural values such as familismo, respect, machismo, marianismo, and fatalism; and the current immigration climate and context negatively and positively affect sexual health. Participants learn skills to overcome socio-cultural and political barriers to accessing health care.

The module also is designed to assist participants to access HIV and STD testing services. It includes information about available services and eligibility and attempts to de-mystify the process of accessing services. Participants learn about the challenges they may face and how to overcome them. Our partnership is committed to supporting the navigation of services as opposed to providing services.

The final module reviews all of the concepts covered in Modules 1–3. It also includes information about abstinence and activities designed to explore what it is to live with HIV. We also developed a resource guide that gives interventionists detailed information to provide to participants who seek linkages to other local services and care.

DISCUSSION

Currently there are no known efficacious HIV/STD prevention interventions for Hispanic/Latino MSM (CDC, 2014b). If HOLA en Grupos is determined to be efficacious, it will contribute to filling a critical gap in HIV/STD prevention resources for this at-risk population. The intervention is unique because it is designed specifically for Hispanic/Latino MSM. HOLA en Grupos also addresses cultural values shared by Hispanics/Latinos. Furthermore, because, as we have noted earlier, Hispanics/Latinos in NC resemble those in the Southeast more generally, findings from the evaluation of the intervention may be particularly useful for HIV/STD prevention efforts among Hispanic/Latino MSM in this region of the US.

To enhance HOLA en Grupos, the CBPR partnership members blended the real lived experiences of Hispanic/Latino MSM, locally collected data, and sound science. The intervention also has features that have been identified by research as characteristic of effective HIV prevention interventions, including incorporating locally collected data and tailoring to a specific and defined audience; being gender specific; having a solid theoretical foundation; incorporating discussions of barriers to, and facilitators of, sexual health; exploring gender norms and expectations; increasing self-esteem and group pride; increasing risk reduction norms and social support for protection; building skills to perform technical, personal, or interpersonal skills through role plays and practice; and offering guidance on how to utilize available services (Herbst, Kay, et al., 2007; Huedo-Medina et al., 2010; Lyles, Crepaz, Herbst, & Kay, 2006; Lyles et al., 2007; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011).

Lessons Learned

We were able to successfully complete our enhancement process thanks to our CBPR partnership’s history of collaborative intervention development, implementation, and evaluation. This provided us with a strong experience base on which to build, and established processes that helped to ensure that the perspectives, insights, and experiences of all partners were incorporated.

Another lesson learned during the enhancement process was our insufficient understanding of the community of Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latina/o transgender persons. Because of our partnership’s commitment to an assets-focused orientation to research that includes the support of building communities, we shifted from a focus on referring to individuals as members of an HIV risk behavior-based category (MSM) to using language that addresses their identities. After all, a tenet of CBPR is the harnessing of identities of community members and not removing them from their contexts and supports (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Rhodes, 2012). Thus, we initially designed HOLA en Grupos to be inclusive of gay and bisexual men and MSM. However, during the enhancement process, we realized that HOLA en Grupos did not acknowledge and address the concerns and contexts of transgender persons. For instance, the “H” in HOLA en Grupos intervention stood for “hombres” (men), and yet, some participants who met inclusion criteria may not self-identify as men. We quickly revised the intervention name. We continued to use HOLA en Grupos as the intervention name, but we stopped using the language formerly used to explain the HOLA acronym - Hombres Ofreciendo Liderazgo y Apoyo en Grupos. We also removed this language from intervention logos, t-shirts, caps, and all printed materials, and revised all language within the modules to include “transgender persons,” in addition to “gay and bisexual men and other MSM”. We updated information to include rates of HIV and STDs among transgender persons, revised role plays to include realistic transgender scenarios, and ensured that all visuals included images of transgender women in addition to men. Transgender-inclusive language and images and transgender-positive activities have been appreciated by transgender participants, and MSM participants have also welcomed the additions.

Enhancing an intervention with CDC partners also added new challenges. It required a new level of professionalism for community partners, including those representing the community organizations. Some were not accustomed to calling into and actively participating in regularly scheduled conference calls or describing a linear and systematic enhancement process with CDC partners (e.g., developing the logic model). Furthermore, because there were fewer ongoing and face-to-face interactions with CDC partners, given the distance between our partnership in NC and our CDC partners in Atlanta, it took time to establish trust and common understandings around the research and partnership.

Conclusions

We are now well into the fourth decade since the identification of HIV, an efficacious vaccine and effective cure remain elusive, and Hispanic/Latino and African American/black MSM continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. Linking persons who have been tested for HIV and are infected to treatment has received increasing emphasis (CDC, 2011a). Linkage to care, along with the availability of other biomedical prevention approaches, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for those who are HIV negative and anti-retroviral treatment to reduce viral load among those who are HIV positive, makes it possible for individuals to lead longer, healthier lives and reduces the likelihood that they will infect others (CDC, 2011b; The White Office of National AIDS Policy, 2010). Primary prevention of HIV risk through behavior change has been found to be an effective strategy for reducing HIV exposure and transmission and remains an important prevention tool, and complements combination prevention approaches that include HIV testing, linkage to, and retention in HIV treatment and care (CDC, 2011a). HOLA en Grupos promotes condom use and HIV/STD testing in a particularly vulnerable segment of MSM. Furthermore, it represents an important effort by members of the Hispanic/Latino MSM community to promote the wellbeing of its members. If the current CDC-supported evaluation determines that HOLA en Grupos is efficacious, it will be the first such behavioral HIV/STD prevention intervention to be identified for potential use with Hispanic/Latino MSM, thereby contributing to the body of evidence-based resources that may be used for preventing HIV/STD infection among these MSM and their sex partners.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the enhancement process and the evaluation study described herein was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to Wake Forest School of Medicine under cooperative agreement U01PS001570. The authors acknowledge the past and current members of the CBPR partnership including Jose Alegria-Ortega, Stacy Duck, and Florence Simán.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Dieguez A, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Nieves L, Diaz F, Decena C, Balan I. A randomized controlled trial to test an HIV-prevention intervention for Latino gay and bisexual men: lessons learned. AIDS Care. 2005;17(3):314–328. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331314303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation of innovative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention interventions for high-risk minority populations. Federal Register. 2004;69:42183–42190. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluating locally-developed (homegrown) HIV prevention interventions for African-American and Hispanic/Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) Federal Register. 2009;74(13436) Available at http://www.federalregister.com/Browse/Document/usa/na/fr/2009/2003/2027/e2009-6854?search=Homegrown#69463781. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High-Impact HIV Prevention: CDC’s Approach to Reducing HIV Infections in the United States. Atlanta, GA: National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; 2011a. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_NHPC_Booklet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategic Plan, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention 2011–2015. Atlanta, GA: National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; 2011b. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2011. Vol. 23. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2012. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Collins CB, Tomlinson HL. Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based behavioral HIV prevention interventions through community engagement: The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) experience. In: Rhodes SD, editor. Innovations in HIV Prevention Research and Practice through Community Engagement. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 239–261. [Google Scholar]

- Diallo DD, Moore TW, Ngalame PM, White LD, Herbst JH, Painter TM. Efficacy of a single-session HIV prevention intervention for black women: A group randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):518–529. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, NY: Seabury Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith JS, Herbst JH, Whittier DK, Jones PL, Smith BD, Uhl G, Fisher HH. Taxonomy for strengthening the identification of core elements for evidence-based behavioral interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(5):872–885. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, Rhodes SD. HIV testing among immigrant sexual and gender minority Latinos in a US region with little historical Latino presence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013a;27(11):628–636. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, Rhodes SD. Immigrant sexual minority Latino men in rural North Carolina: An exploration of social context, social behaviors, and sexual outcomes. J Homosex. 2013b doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.872507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SD. Ballgames and Boundaries. In: Scarborough VL, Wilcox DR, editors. The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press; 1991. pp. 317–345. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW. From research to “best practices” in other settings and populations. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(3):165–178. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, McNally T, Passin WF, Kay LS, Johnson RL. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4 Suppl):S38–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(1):25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Painter TM, Tomlinson HL, Alvarez ME. Evidence-based HIV/STD prevention intervention for black men who have sex with men. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63:21–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, Lacroix JM, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995–2008: A meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Introduction to methods in community-based participatory research for health. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelvin EA, Mantell JE, Candelario N, Hoffman S, Exner TM, Stackhouse W, Stein ZA. Off-label use of the female condom for anal intercourse among men in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2241–2244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P, Kovacs S, Anderson-Smits C, Schmidt N, Salinas O, Hembling J, Shedlin M. Patterns and predictors of HIV/STI risk among Latino migrant men in a new receiving community. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):199–213. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9945-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar RR, Suro R, Tafoya S. The New Latino South: The Context and Consequence of Rapid Population Growth. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lauby JL, LaPollo AB, Herbst JH, Painter TM, Batson H, Pierre A, Milnamow M. Preventing AIDS through live movement and sound: Efficacy of a theater-based HIV prevention intervention delivered to high-risk male adolescents in juvenile justice settings. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(5):402–416. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Kay LS. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of the CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):21–31. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, Mullins MM. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Capoferro C. The geographic diversification of American immigration. In: Massey DS, editor. New Faces in New Places. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, Jones P, Harshbarger C, Collins C, Carey JW. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):59–73. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Epidemiologic profile for HIV/STD prevention & care planning. Raleigh, NC: NC Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Painter TM. Connecting the dots: When the risks of HIV/STD infection appear high but the burden of infection is not known - The case of male Latino migrants in the Southern United States. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):213–226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter TM, Ngalame PM, Lucas B, Lauby JL, Herbst JH. Strategies used by community-based organizations to evaluate their locally developed HIV prevention interventions: Lessons learned from the CDC’s innovative interventions project. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(5):387–401. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.5.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Demonstrated effectiveness and potential of CBPR for preventing HIV in Latino populations. In: Organista KC, editor. HIV Prevention with Latinos: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Oxford; 2012. pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Daniel J, Aronson RE. Using community-based participatory research to prevent HIV disparities: Assumptions and opportunities identified by The Latino Partnership. Journal of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes. 2013;63(Supplement 1):S32–S35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Downs M, Aronson RE. Intervention trials in community-based participatory research. In: Blumenthal D, DiClemente RJ, Braithwaite RL, Smith S, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research: Issues, Methods, and Translation to Practice. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montano J, Alegria-Ortega J. Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(2):146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Felizzola J, Wolfson M, McGuire J. Latino men who have sex with men and HIV in the rural southeastern USA: findings from ethnographic in-depth interviews. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(7):797–812. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.492432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montano J. Outcomes from a community-based, participatory lay health adviser HIV/STD prevention intervention for recently arrived immigrant Latino men in rural North Carolina. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 suppl):103–108. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montano J, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, Bowden WP. Using community-based participatory research to develop an intervention to reduce HIV and STD infections among Latino men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(5):375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Davis AB, Hannah A, Marsiglia FF. Boys must be men, and men must have sex with women: A qualitative CBPR study to explore sexual risk among African American, Latino, and white gay men and MSM. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5(2):140–151. doi: 10.1177/1557988310366298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Kelley C, Simán F, Cashman R, Alonzo J, Wellendorf T, Reboussin B. Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) to develop a community-level HIV prevention intervention for Latinas: A local response to a global challenge. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(3):293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(3):173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Alonzo J, Downs M, Abraham C, Miller C, Reboussin BA. CBPR to prevent HIV within ethnic, sexual, and gender minority communities: Successes with long-term sustainability. In: Rhodes SD, editor. Innovations in HIV Prevention Research and Practice through Community Engagement. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Martinez O, Song EY, Daniel J, Alonzo J, Eng E, Reboussin B. Depressive symptoms among immigrant Latino sexual minorities. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2013;37(3):404–413. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.3.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Wolfson M, Alonzo J, Eng E. Prevalence estimates of health risk behaviors of immigrant Latino men who have sex with men. J Rural Health. 2012;28(1):73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Vissman AT, DiClemente RJ, Duck S, Hergenrather KC, Eng E. A randomized controlled trial of a culturally congruent intervention to increase condom use and HIV testing among heterosexually active immigrant Latino men. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(8):1764–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern AIDS Coalition. Southern States Manifesto: Update 2012- Policy Brief and Recommendations. 2012:39. [Google Scholar]

- The White Office of National AIDS Policy. [Accessed on: February 28, 2014];National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010 Available at: http://aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas.pdf.

- US Census Bureau. [Accessed February 18, 2014];2014 Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html.

- Williamson E. The Penguin History of Latin America. Penguin Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilton L, Herbst JH, Coury-Doniger P, Painter TM, English G, Alvarez ME, Carey JW. Efficacy of an HIV/STI prevention intervention for black men who have sex with men: findings from the Many Men, Many Voices (3MV) project. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(3):532–544. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]