Abstract

Importance

Advance care planning (ACP) may prevent end-of-life (EOL) care that is non-beneficial and discordant with patient wishes. Despite long-standing recognition of the merits of ACP in oncology, it is unclear whether cancer patients’ participation in ACP has increased over time.

Objective

To characterize trends in durable power of attorney (DPOA) assignment, living will creation, and participation in discussions of EOL care preferences, and to explore associations between ACP subtypes and EOL treatment intensity, as reflected in EOL care decisions and terminal hospitalizations.

Design

Prospectively collected survey data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), including data from in-depth “exit” interviews conducted with next-of-kin surrogates following the death of an HRS participant. Trends in ACP subtypes were tested, and multivariable logistic regression models examined associations between ACP subtypes and measures of treatment intensity.

Setting

HRS, a nationally representative, biennial, longitudinal panel study of U.S. residents over age 50.

Participants

1,985 next-of-kin surrogates of HRS participants with cancer who died between 2000 and 2012.

Main Outcome and Measures

Trends in the surrogate-reported frequency of DPOA assignment, living will creation, and participation in discussions of EOL care preferences, as well as associations between ACP subtypes and surrogate-reported EOL care decisions/terminal hospitalizations.

Results

From 2000-2012, there was an increase in DPOA assignment (52% to 74%, p=0.03), without change in use of living wills (49% to 40%, p=0.63) or EOL discussions (68% to 60%, p=0.62). Surrogates increasingly reported that patients received “all care possible” at EOL (7% to 58%, p=0.004), and rates of terminal hospitalizations were unchanged (29% to 27%, p=0.70). Both living wills and EOL discussions were associated with limiting/withholding treatment [living will: adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=2.51, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.53-4.11, p<0.001; EOL discussions: AOR=1.93, 95% CI=1.53-3.14, p=0.002], while DPOA assignment was not.

Conclusions and Relevance

Use of DPOA increased significantly between 2000 and 2012, but was not associated with EOL care decisions. Importantly, there was no growth in key ACP domains such as discussions of care preferences. Efforts that bolster communication of EOL care preferences and also incorporate surrogate decision-makers are critically needed to ensure receipt of goal-concordant care.

Introduction

In response to concerns about the quality of end-of-life (EOL) care provided to patients with chronic illnesses approaching death, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently released a report entitled Dying in America.(1) The IOM report describes EOL care in the United States (U.S.) as intensive and frequently inconsistent with patients’ preferences. The report advocates for a broader definition of advance care planning (ACP), characterized by ongoing clinician-patient discussions of EOL care preferences over time, to help ensure goal-concordant care at EOL.

ACP is particularly relevant to oncology, as cancer is the second leading cause of mortality in the U.S., with more than half a million cancer-related deaths in 2013.(2) Moreover, compared to common non-cancer causes of death, cancer has a distinct trajectory of functional decline with a more predictable terminal period which may be more conducive to ACP and palliative care.(3, 4) Professional oncologic organizations have long realized the value of early ACP as a key component of optimal palliative care, as reflected in National Comprehensive Care Network (NCCN) guidelines since 2001.(5) Similarly, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has endorsed early ACP as far back as 1998, with continued emphasis in more recent statements.(6-8)

Nevertheless, evidence suggests that cancer care continues to be both highly intensive and geographically variable, likely driven in large part by local practice patterns instead of patients’ preferences.(9-14) Indeed, reports published over a decade ago that described an environment of increasingly aggressive cancer care are mirrored in more recent studies showing persistent use of hospital-based services near death, despite evidence that aggressive EOL interventions may not be associated with better medical or quality of life outcomes.(15-20)

In light of the continued intensity of EOL cancer care, it is important to examine whether oncologists’ long-standing recognition of the merits of ACP have translated into gains in patient participation in ACP and whether certain forms of ACP are more strongly linked to EOL treatment intensity. To address this question, we sought to characterize trends in ACP and EOL treatment intensity in a cohort of cancer patients who participated in a nationally representative survey and who died over a 12-year period from 2000 to 2012.

Methods

Study population

We analyzed survey data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative, longitudinal panel survey that conducts biennial interviews with a sample of more than 26,000 U.S. residents over age 50 and their spouses. The HRS is designed to collect detailed health, demographic, and financial information about older adults and has been described previously.(21, 22) Following the death of study participants, HRS conducts in-depth “exit interviews” with a proxy informant who is knowledgeable about the deceased respondent, often the next-of-kin. Exit informants are asked detailed questions about the study participant's EOL experience, including questions about the medical care received. Exit interview response rates are high, with reported rates over 85% since 2000.(23) Given our interest in understanding patterns of ACP amongst cancer patients, we examined responses from proxy informants of decedents who died between 2000 and 2012 and had either: 1) died from cancer, or 2) received cancer treatment during the last two years of life, as noted by the proxy informant. Oral informed consent was obtained from study participants and proxies as part of the HRS process. Additionally, our study was approved by the institutional review board of Johns Hopkins Hospital (Baltimore, MD).

Advance care planning and EOL treatment intensity

For our analysis, we broadened our definition of ACP beyond traditional advance directives to be consistent with the IOM's recommendation. As such, ACP was defined as the presence of a living will, assignment of a durable power of attorney (DPOA), or participation in a discussion about EOL care preferences prior to death, as noted by the proxy informant. For living wills, informants were asked: “Did [first name] provide written instructions about the treatment or care [she/he] wanted to receive during the final days of [her/his] life?” For DPOA, informants were asked: “Did [first name] make any legal arrangements for a specific person or persons to make decisions about [his/her] care or medical treatment if [he/she] could not make those decisions [himself/herself]?” For EOL care discussions, informants were asked: “Did [first name] ever discuss with you or anyone else the treatment or care [he/she] wanted to receive in the final days of [his/her] life.” To assess the intensity of EOL care, proxy informants were asked whether “all care possible under any circumstances in order to prolong life” was delivered at EOL or whether certain treatments were limited or withheld. Additionally, we examined the percentage of decedents who experienced proxy-reported terminal hospitalizations over time as another measure of EOL treatment intensity, since hospital deaths are associated with worse mental health outcomes in bereaved caregivers.(24) Of note, proxy informants were the primary decision-makers for the decedent's EOL care in 79% of cases that required surrogate decision-making. These proxy reports of ACP and EOL treatment intensity have used previously in palliative care research.(25, 26)

Statistical analysis

We utilized a multivariable logistic regression model to evaluate the association between year of death and ACP, with adjustment for multiple decedent characteristics, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, level of education, marital status, type of religion, importance of religion to the decedent, time from cancer diagnosis to death, medical co-morbidities, veteran status, residence in a nursing home, geographic region, year of death, and relationship of the proxy to the decedent. We subsequently tested a null hypothesis of the absence of a linear trend in the use of ACP over time by performing a contrast test on the individual variable coefficients corresponding to each year of death from our multivariable model.(19) Specifically, we tested if a linear combination of the year of death variable coefficients summed to zero, using 2000 as the baseline reference year and applying equally spaced, sum-to-zero weights. We also performed multivariable analysis to characterize the association between year of death and measures of treatment intensity and similarly applied the contrast test to assess for a linear trend in treatment intensity over time. Additionally, we utilized multivariable logistic regression to characterize associations between ACP subtypes and measures of treatment intensity, adjusting for the covariates described above. A logistic regression model was fit to each outcome variable separately. In addition, when calculating an adjusted odds ratio for a particular ACP subtype, variables that corresponded to the presence of other ACP subtypes were included as covariates in order to isolate the independent association between a particular ACP subtype and measures of treatment intensity.

Of note, HRS selects its participants using a complex, multi-stage, area probability sampling design, in which geographic units that are representative of the nation are defined and age-eligible members of households within these units are screened with an in-person interview.(27) Because HRS oversamples African-Americans and Hispanics, respondent-level and household-level weights are created such that the weighted HRS sample is representative of all U.S. households that contain at least one age-eligible member, with post-stratification weights based on the Current Population Survey (CPS). In all calculations, we accounted for the complex sampling design by applying respondent-level sampling weights that were taken from the last interview in which the decedent participated prior to death.

Throughout the analysis, two-sided significance testing was used, and a P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata software (Stata/IC10.0).

Results

A total of 8,193 HRS participants died between 2000 and 2012 and had exit interviews completed by proxy informants. Of these decedents, 2,040 (25%) either died from cancer or received active cancer treatment in the last two years of life. Complete information regarding living will status, DPOA assignment, and participation in EOL discussions was unavailable for 55 decedents (3%), who were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 1,985 decedents served as our study population. The relationship of proxy informants to the decedent was most commonly a spouse/partner (43%), son/daughter (38%), sibling (5%), or other (14%). Median time from death to exit interview was 12 months (range: 1-36 months).

Overall, 81% of decedents in our cohort had engaged in at least one form of ACP, including 48% who had completed a living will, 58% who had designated a power of attorney, and 62% who had engaged in discussions regarding their EOL care preferences, as noted by the proxy. Table 1 shows the baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the decedent population by ACP participation. Decedents who did not participate in any form of ACP were more likely to be male, African-American, Hispanic, married, and to consider religion to be an influential factor in their lives, compared with those who did engage in ACP (all p<0.05). They were also less likely to be widowed or have completed high school or college (all p<0.01).

Table 1.

Decedent Characteristicsa

| Characteristicb | Any advance planning (N=1601) | No advance planning (N=384) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at death, yrs (IQR) | 74.7 (74.1-75.4) | 73.5 (72.2-74.8) | 0.13 |

| Female, % | 47.4 | 40.6 | 0.04 |

| Racec, % | <0.001 | ||

| Caucasian | 89.7 | 72.0 | |

| African-American | 7.8 | 22.7 | |

| Other | 2.4 | 5.3 | |

| Hispanic ethnicityc, % | 3.2 | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Education, % | <0.001 | ||

| Less than high-school graduate | 26.4 | 43.8 | |

| High-school graduate | 53.2 | 41.0 | |

| Some college completed | 20.3 | 15.2 | |

| Marital status, % | 0.008 | ||

| Married | 51.9 | 61.5 | |

| Widowed | 31.6 | 21.0 | |

| Separated/divorced | 12.5 | 12.1 | |

| Single | 3.8 | 5.3 | |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Religion, % | 0.07 | ||

| Protestant | 60.0 | 65.9 | |

| Catholic | 28.0 | 28.3 | |

| Jewish | 2.5 | 1.2 | |

| No preference | 8.2 | 4.0 | |

| Other | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Importance of religion, % | <0.001 | ||

| Very important | 54.1 | 67.9 | |

| Somewhat important | 30.0 | 25.7 | |

| Not too important | 15.9 | 6.3 | |

| Veteran, % | 33.9 | 30.1 | 0.24 |

| Nursing home resident, % | 25.0 | 20.8 | 0.16 |

| Time from cancer diagnosis to death, yrs (IQR) | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 1.0 (0.5-2.0) | 0.54 |

| Co-morbid medical conditions, % | |||

| Heart disease | 39.2 | 35.2 | 0.22 |

| Chronic lung disease | 26.7 | 22.3 | 0.15 |

| Prior stroke | 16.4 | 16.8 | 0.88 |

| Memory-related disease | 8.5 | 5.8 | 0.10 |

| Regiond, % | 0.002 | ||

| New England | 6.1 | 6.5 | |

| Mid-Atlantic | 12.6 | 11.3 | |

| East North Central | 18.6 | 13.6 | |

| West North Central | 8.1 | 8.0 | |

| South Atlantic | 22.3 | 28.9 | |

| East South Central | 5.3 | 6.8 | |

| West South Central | 9.7 | 15.9 | |

| Mountain | 4.5 | 3.7 | |

| Pacific | 12.9 | 5.5 | |

Percentages are weighted using the sampling weights from the Health and Retirement Study. Totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Missing data include: Race 0.4%; Hispanic ethnicity 0.3%; Education 0.5%; Marital status 0.6%; Religion 0.7%; Importance of religion 2.0%; Veteran status 0.7%; Nursing home resident status 0.1%; Time from diagnosis to death 11.7%; Heart disease 1.2%; Lung disease 1.5%; Stoke 0.9%; Memory-related disease 1.8%

Race and ethnicity were both self-reported in the Health and Retirement Study

Regions: New England (ME, NH, VT, MA, RI, CT), Mid-Atlantic (NY, NJ, PA), East North Central (OH, IL, IN, MI, WI), West North Central (MN, IA, MO, ND, SD, NE, KA), South Atlantic (DE, MD, DC, VA, WV, NC, SC, GA, FL), East South Central (KY, TN, AL, MS), West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TK), Mountain (MT, ID, WY, CO, NM, AZ, UT, NV), Pacific (WA, OR, CA, AK, HI)

Abbreviations: IQR, inter-quartile region; EOL, end-of-life

Figure 1 illustrates adjusted levels of ACP participation over time, as reported by the proxy. Over the study period, there was no significant increase in the percentage of decedents who engaged in any form of ACP (p=0.19). Similarly, there were no significant changes in the use of living wills (p=0.63) or participation in EOL discussions (p=0.62). There was, however, a significant increase in the frequency of DPOA assignment (p=0.03). As an example, the adjusted percentage of decedents who designated a DPOA increased from 52% in 2000 to 74% in 2012.

Figure 1.

Adjusted yearly percentages of advance care planning (ACP) and subtypes over time

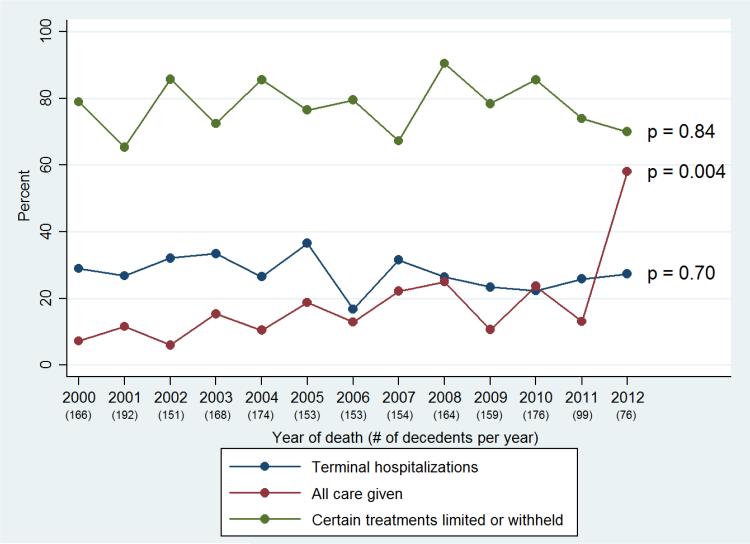

Figure 2 displays the adjusted yearly percentages of measures of EOL treatment intensity among decedents over time, as reported by the proxy. Over the study period, there were no significant changes in the percentage of decedents who experienced terminal hospitalizations (p=0.70) or the percentage of decedents who had treatments limited or withheld at EOL (p=0.84). However, there was a significant increase in the percentage of decedents who received all care possible at EOL (p=0.004). As an example, the adjusted percentage of decedents who received all care at EOL rose from 7% for decedents in 2000 to 58% for decedents in 2012.

Figure 2.

Adjusted yearly percentages of end-of-life (EOL) treatment intensity over time

*Note that no figure legends were thought to be necessary.

As shown in Table 2, creation of a living will was significantly associated with increased odds of having treatments limited or withheld at EOL [adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=2.51, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.53-4.11]. Similarly, participation in EOL discussions was also significantly associated with increased odds of having treatments limited or withheld at EOL (AOR=1.93, 95% CI: 1.53-3.14). Conversely, DPOA assignment was not associated with having treatments limited or withheld at EOL, but was associated with decreased odds of experiencing a terminal hospitalization (AOR=0.70, 95% CI: 0.52-0.94). As an example of the influence of ACP subtype on care decisions, treatments were limited or withheld in 88% of decedents who had both a living will and EOL discussions, while treatments were limited or withheld in only 53% of decedents who had neither a living will nor an EOL discussion. In both scenarios, the presence of a DPOA did not appreciably alter these care decisions (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 2.

Associations between advance care planning and EOL treatment intensity

| ACP subtype | Certain treatments limited or withheld (N=1316) | All care possible given (N=204) | Terminal hospitalizations (N=597) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discussion of EOL care preferences | 1.93** (1.53-3.14) | 0.58* (0.36-0.92) | 0.83 (0.63-1.08) |

| Living will | 2.51*** (1.53-4.11) | 0.49** (0.29-0.84) | 0.93 (0.69-1.25) |

| Durable power of attorney | 1.52 (0.78-2.66) | 0.68 (0.41-1.10) | 0.70* (0.52-0.94) |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, marital status, religion, importance of religion to decedent, veteran status, whether patient lived in nursing home, time from diagnosis to death, co-morbidities, geographic region, year of death, relationship of the proxy to the decedent and other forms of ACP.

Abbreviations: EOL, end-of-life

Other factors associated with increased odds of receiving all care possible at EOL included African-American race (AOR=1.92, 95% CI: 1.03-3.42) as compared to Caucasian race and Hispanic ethnicity (AOR=3.69, 95% CI: 1.54-8.87) as compared to non-Hispanic ethnicity. Similarly, African-American race was associated with higher odds of dying in the hospital (AOR=1.63, 95% CI: 1.11-2.40), as was geographic region (New England: AOR=1.88, 95% CI: 1.09-3.25; mid-Atlantic: AOR=1.90, 95% CI: 1.25-2.87).

To address potential bias from variation in the relationship between proxy and decedent, a sensitivity analysis was performed in the 21% of proxy informants who did not report being primary decision-makers for incapacitated decedents. In this subset, the multivariable model yielded similar results. EOL discussions continued to be associated with increased odds of having treatments limited or withheld at EOL (AOR=2.05, 95% CI: 1.26-3.35), as did creation of a living will (AOR=2.00, 95% CI: 1.17-3.42), while DPOA assignment was not associated with having treatments limited or withheld at EOL, but was associated with decreased odds of experiencing a terminal hospitalization (AOR=0.70, 95% CI: 0.49-0.98).

Discussion

Using nationally representative survey data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we examined use of ACP among cancer patients over time, as reported by proxy informants. We found that DPOA assignment was the only ACP domain that increased significantly between 2000 and 2012, despite increasing recognition of the merits of early ACP by patients, physicians, and health care payors over this time period.(28, 29) Conversely, use of living wills and participation in EOL care discussions did not increase significantly; in 2012, 40% of study participants still had not discussed their EOL care preferences prior to death.

Importantly, DPOA assignment was the only form of ACP which was not associated with decisions to limit or provide all care possible at EOL, as reported by the proxy. Decedents who were most likely to receive aggressive EOL care were those who did not have a living will and had not discussed their EOL treatment preferences prior to death; among this group, the assignment of a DPOA did not further reduce the likelihood of receiving aggressive EOL care. Taken together, these findings suggest that if patients’ EOL treatment preferences have not been explicitly communicated, either through writing or conversation, health care proxies may default to providing all care possible, instead of limiting potentially intensive, life-prolonging care.

Multiple indicators of EOL treatment intensity suggest that cancer care in the U.S. continues to be intensive, with evidence of increasing rates of hospitalizations, ICU stays, and emergency department visits in the last month of life, along with persistently high rates of terminal hospitalizations, late hospice referrals, and burdensome transitions near death.(9-13, 16, 19) In this cohort, between 25-30% of terminally-ill cancer patients died in the hospital, consistent with what others have found.(12, 19) Additionally, patients were more likely to receive all potentially life-prolonging care at EOL over time, not less. Whether these findings are concordant with patient preferences is unclear, but considerable research suggests that terminally-ill patients often receive care that is more intensive than their stated treatment preferences.(30-32)

Given the stagnant growth in both living will creation and participation in EOL discussions, despite evidence of their association with reduced EOL treatment intensity, new avenues must be pursued for bolstering their adoption. Pioneering health system initiatives provide precedent for how this may be accomplished.(33) In La Crosse, Wisconsin, reported rates of written advance directives amongst decedents have exceeded 80%.(34) The widespread uptake in ACP has been achieved through general awareness campaigns that promote ACP and an electronic record system that prompts all patients reaching age fifty-five to discuss their EOL care preferences with their primary care provider, among other initiatives. Other healthcare systems have described similar success with electronic prompts encouraging patient engagement in ACP and modifications of the electronic record to ensure clear communication of patients’ wishes.(33) Further gains in ACP may also be seen on a policy level through payment reform. Although initial Medicare proposals to reimburse clinician engagement in ACP were derailed by sensationalized rhetoric likening such discussions to “death panels,” more recent proposals that include financial incentives for both clinician and patient engagement in EOL care discussions have gained bipartisan support.(35, 36) Whether a one-time reimbursement will have significant impact on outcomes is unclear given the importance of ongoing discussions, but the reemergence of dialogue on the subject is encouraging.

Importantly, our findings also highlight the limitations of the DPOA when EOL care preferences have not been communicated to surrogate decision-makers. Interviews with surrogates consistently illustrate that a familiarity with patient preferences eases decision-making, reduces decisional regret, and improves caregivers’ bereavement outcomes.(18, 37-39) As such, it is critical that health care agents and caregivers are integrated into each step of the ACP process, including ongoing clinician-patient discussions of prognosis, goals of care, and treatment preferences with respect to foreseeable potential interventions.(1, 40, 41) Indeed, significant gains in surrogate understanding of patient preferences have been demonstrated with the use of structured interviews on ACP that involve the patient, surrogate, and a trained facilitator, who does not have to be a physician.(42-44) Wider adoption of these tools will be a key component of better EOL care.(44)

Interestingly, although DPOA assignment was not associated with EOL care decisions, it was associated with lower rates of terminal hospitalizations compared with other ACP subtypes, as reported by the proxy. Terminal hospitalizations have been previously linked to worse patient quality-of-life, increased psychiatric morbidity in caregivers, and significant EOL spending, but unfortunately still occur with significant frequency.(12, 17-19, 24) While a better understanding of the drivers of terminal hospitalizations is needed, recent studies have implicated uncontrolled symptoms as a common source of late hospitalizations in advanced cancer patients, a scenario which could be preventable with better access to outpatient palliative services.(45, 46). In fact, early introduction of outpatient palliative services has been associated with a number of improved end-of-life care measures, including fewer ER visits, hospital admissions, and ICU admissions, perhaps through better symptom management and/or ACP, highlighting the urgency of filling the current void of outpatient palliative clinics.(47, 48) Ultimately, the mechanism for how ACP subtypes influence patients’ location of death is likely complex, and should be further explored.(26, 49)

Lastly, our findings confirm well-documented racial and ethnic disparities in ACP and EOL treatment intensity amongst cancer patients, a complex multi-factorial issue rooted in varying patient preferences, family values, religious views, and understanding of prognosis.(50-53) Rapid expected growth of the minority elderly population in the coming years underscores the critical nature of interventions that can help ensure goal concordant care in minority populations.(54, 55)

Although our study has many strengths, it also has a few limitations. Foremost, information on ACP and EOL treatment decisions was obtained from proxy informants. While retrospective ascertainment of data from proxies is common in palliative care research, it is subject to recall and social desirability biases. Studies that have measured the level of discord between prospectively collected patient-reported data at end-of-life and retrospectively collected proxy-reported estimates of the same items have shown that discord is greatest for subjective domains such as pain and depression, whereas proxy responses for objective items such as place of death have shown high accuracy.(56-58) Notably, in the setting of cancer, the discordance between decedents and their proxy respondents has been modest.(59) Our study contained two subjective endpoints, namely the provision of all care possible and limiting/withholding treatment, which may have been influenced by the proxy's own positive or negative experience during the decedents’ end-of-life period. While questions regarding the presence of advance directives were more objective in nature, the accuracy of proxy responses for these items is also unclear. As such, we undertook a number of measures to minimize bias related to proxy-reporting. Both the proxy's relationship to the decedent and the time from the decedent's death to the exit interview were included in the multivariable model; neither variable was independently associated with any of the endpoints. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis indicated that the study findings were not affected by whether the proxy was the primary decision-maker. Moreover, if social desirability did influence proxy report of EOL treatment intensity, there is no reason to suspect that this bias followed the trends that we observed. If anything, one would expect social desirability to increasingly influence proxies to report reduced EOL treatment intensity with better recognition of the harms of intense EOL care. Additionally, the proxy's recollection of the decedent's engagement in ACP provides intrinsic value, as ACP that occurred without the proxy's knowledge was likely ineffective given the fact that the proxy was usually the primary decision-maker. Further limitations include an inability to generalize our results to populations of cancer patients that were not well-represented in our cohort, for example younger patients, and the lack of complete documentation of decedents’ EOL care preferences, a key component of assessing goal-concordant care and an important area of future research.

In conclusion, over the 12-year period from 2000-2012, growth in ACP amongst cancer patients was modest, and predominantly focused on DPOA assignment without an accompanying increase in either EOL discussions or living wills. Without written or verbal direction, surrogate decision-makers may struggle to make care decisions consistent with patient preferences. As such, policy and health system initiatives that support wider adoption of clinician-patient discussions of EOL care preferences are essential. Additionally, these conversations must also including surrogate decision-makers, as efforts to educate surrogates on the goals, values, and care preferences of their loved ones have proven valuable across multiple chronic disease sites(42, 43), and should be further explored in patients with advanced cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Narang had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Nicholas is supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Aging (K01AG041763). Dr. Wright is supported by a career development award from the National Cancer Institute (K07CA166210). Neither the National Institute of Aging nor the National Cancer Institute had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This work has not been previously presented or published in any form. This work has not been previously presented or published.

Footnotes

No other financial disclosures or conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leading causes of death [Internet] Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [December 1, 2014]. [updated July 14, 2014]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teno JM, Weitzen S, Fennell ML, Mor V. Dying trajectory in the last year of life: does cancer trajectory fit other diseases? J Palliat Med. 2001;4(4):457–64. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy MH, Weinstein SM, Carducci MA. NCCN Palliative Care Practice Guidelines Panel. NCCN: Palliative care. Cancer Control. 2001;8(6 Suppl 2):66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1986–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American society of clinical oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):755–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy MH, Smith T, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Palliative care, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(10):1379–88. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morden NE, Chang C, Jacobson JO, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(4):786–96. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JW, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309(5):470–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Chang C, et al. Quality of end-of-life cancer care for Medicare beneficiaries: Regional and hospital-specific analyses. A report of the Dartmouth Atlas Project. 2010:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman D, Morden N, Chang C, Fisher E, Wennberg J. Trends in cancer care near the end of life: A Dartmouth Atlas health care brief. 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, Chang C, Goodman D, Morden NE. Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):548–54. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony DL, Herndon MB, Gallagher PM, et al. How much do patients’ preferences contribute to resource use? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):864–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnato AE, Chang CC, Farrell MH, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Is survival better at hospitals with higher “end-of-life” treatment intensity? Med Care. 2010;48(2):125–32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c161e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks GA, Li L, Sharma DB, et al. Regional variation in spending and survival for older adults with advanced cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(9):634–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright AA, Hatfield LA, Earle CC, Keating NL. End-of-life care for older patients with ovarian cancer is intensive despite high rates of hospice use. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3534–39. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):480–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995:S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weird DW. Cohort profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2104;43(2):576–85. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. [December 1, 2014];Health and Retirement Study: sample sizes and response rates [Internet] 2011 Available from: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf.

- 24.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4457–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306(13):1447–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heeringa S, Connor J. Technical description of the Health and Retirement Study sample design. University of Michigan, Survey Research Center at the Institute for Social Research; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr CW, Donohue KA, Tangeman JC, et al. Cost savings and enhanced hospice enrollment with a home-based palliative care program implemented as a hospice–private payer partnership. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(12):1328–35. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly RJ, Smith TJ. Delivering maximum clinical benefit at an affordable price: engaging stakeholders in cancer care. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):e112–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahluwalia SC, Chuang FL, Antonio AL, Malin JL, Lorenz KA, Walling AM. Documentation and discussion of preferences for care among patients with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(6):361–6. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4387–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisognano M, Goodman E. Engaging patients and their loved ones in the ultimate conversation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):203–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. [December 1, 2014];Respecting Choices [Internet] 2015 Available from: http://www.gundersenhealth.org/respecting-choices.

- 35.Personalize Your Care Act of 2013, H.R.1173, 113th Congress, 1st session Sess. 2013.

- 36.Medicare Choices Empowerment and Protection Act, S 2240, 113th Congress, 2nd Session Sess. 2014.

- 37.Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Beyond substituted judgment: How surrogates navigate end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1688–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1274–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried TR, O'Leary JR. Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient-and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1602–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schenker Y, White DB, Arnold RM. What should be the goal of advance care planning? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1093–4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schenker Y, Barnato A. Expanding support for “upstream” surrogate decision making in the hospital. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):377–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song MK, Kirchhoff KT, Douglas J, Ward S, Hammes B. A randomized, controlled trial to improve advance care planning among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Med Care. 2005;43(10):1049–53. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178192.10283.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL. Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1233–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310(6):575–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, et al. Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(1):51–4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hui D, Elsayem A, De La Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1054–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, Dev R, Chisholm G, Bruera E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120(11):1743–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez-Acevedo M, Havrilesky LJ, Broadwater G, et al. Timing of end-of-life care discussion with performance on end-of-life quality indicators in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):156–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and Ethnic Differences in End-of-Life Care in Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries with Advanced Cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):153–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(33):5559–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1140–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Min S, Kutner J. Advance directive discussions: lost in translation or lost opportunities? J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):86–92. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.US Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging. [December 1, 2014];A profile of older Americans. 2013 [Internet]; 2013. Available from: http://www.aoa.acl.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/index.aspx.

- 55.Garrido MM, Harrington ST, Prigerson HG. End-of-Life Care in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209–14. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teno JM. Measuring end-of-life care outcomes retrospectively. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(supplement 1):s,42–s-49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McPherson C, Addington-Hall J. Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(1):95–109. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance Care Planning and the Quality of End-of-Life Care in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209–14. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang ST, McCorkle R. Use of family proxies in quality of life research for cancer patients at the end of life: a literature review. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(7-8):1086–104. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120005928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.