Abstract

Introduction:

The incidence of bladder cancer varies by gender. Whether differences exist between women and men in extent of disease, treatment, and outcome is not well-described. We evaluate gender differences in bladder cancer using a population-based cohort.

Methods:

Electronic records of treatment were linked to the population-based Ontario Cancer Registry to identify all patients with bladder cancer treated with cystectomy or radical radiotherapy (RT) in Ontario between 1994 and 2008. We compare extent of disease at time of cystectomy, treatment, and outcomes between women and men.

Results:

In total, 5259 patients with bladder cancer were treated with cystectomy or radical RT; of these, 25% (n = 1296) were women. There was no gender difference in the proportion of patients treated with cystectomy (75% of women [974/1296], 73% of men [2905/3963], p = 0.189). At the time of cystectomy, women were more likely to have muscle-invasive disease (86% [836/974] vs. 80% [2335/2905], p < 0.001), but less likely to have lymph nodes dissected (68% [664/974] vs. 76% [2210/2905], p < 0.001]. Among the 2944 patients with muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma treated with cystectomy, use of neoadjuvant (5% vs. 4%, p = 0.419) and adjuvant chemotherapy (18% vs. 20%, p = 0.190) did not differ significantly between genders. Five-year cancer-specific survival and overall survival of the full cohort did not differ between women and men (38% vs. 39%, p = 0.522; 33% vs. 33%, p = 0.795).

Conclusions:

This population-based cohort did not demonstrate any substantial differences in extent of disease, treatment, or outcome between women and men treated with cystectomy or radical RT for bladder cancer.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fifth most common cancer diagnosed in Canada, with about 8000 new cases and 2220 deaths each year.1 It is well-known that the incidence of bladder cancer varies by gender.1 About 75% of patients with bladder cancer are men and the reasons for this are not well understood but may relate to gender differences in smoking,2,3 occupational exposures,2,4 or hormonal factors.5 While several studies suggest that women with bladder cancer may have inferior outcomes to men,6–9 this has not been observed consistently.10 Women are more likely to have a delay in diagnosis,11 present with more advanced disease,8 and may have more biologically aggressive disease.12 The existing literature does not describe to what extent treatment patterns for bladder cancer might vary between women and men. The objective of the current study was to describe gender differences in extent of disease, treatment, and outcome among patients treated with cystectomy or radical radiotherapy in the general population of Ontario, Canada.

Methods

Study design and population

This report represents a sub-study of a larger population-based, retrospective cohort study that described local therapy, use of chemotherapy, and outcome of all patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer in Ontario, Canada. Detailed methods and primary results have been reported previously.13,14 All incident cases of bladder cancer in Ontario with transitional cell, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell histology that underwent cystectomy or radical radiotherapy (RT) between 1994 and 2008 were included. Ontario has a population of about 13.5 million people and a single-payer universal health insurance program.

Data sources

The Ontario Cancer Registry (OCR) is a passive, population-based cancer registry that captures diagnostic and demographic information on at least 98% of all incident cases of cancer in the province of Ontario.15 The OCR does not compile information about extent of disease or treatment. Accordingly, we obtained surgical pathology reports for patients with cystectomy. Indicators of the socioeconomic status (SES) of the community in which patients resided at diagnosis were linked as described previously.16

A variety of electronic administrative health databases were linked to the OCR. Records of hospitalization from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) provided information about surgical interventions; these records are known to be consistent and complete.17 The clinical databases of Ontario’s comprehensive cancer centres provided records of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. These centres are the only providers of RT in the province. Provincial physician billing records and treatment records from regional cancer centres were used to identify chemotherapy utilization. Surgical pathology reports for patients treated with cystectomy were obtained from OCR and reviewed by a team of data abstractors.

Definitions of comorbidity, management, and outcomes

Comorbidity was classified using the Charlson Index modified for administrative data based on all non-cancer diagnoses recorded during any hospital admission within 5 years prior to surgery.18 Consultation with a radiation oncologist was identified based on unique Ontario Health Insurance Program (OHIP) billing codes used by radiation oncologists. As a proxy measure of medical oncologists, we identified the 220 physicians who submitted billing records for muscle-invasive bladder cancer with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or adjuvant chemotherapy in 1994–2008. We have used a similar approach elsewhere.19,20 Each surgical case was considered to have been seen by a radiation oncologist/medical oncologist in the pre-operative and/or postoperative setting if any of these physicians submitted visit billing codes for that patient within 16 weeks before and/or after surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was defined as any chemotherapy administered within 16 weeks prior to surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy was defined as any chemotherapy administered within 16 weeks after surgery. Complete information about vital status in the OCR was available up to December 31, 2012; cause of death was available up to December 31, 2010.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of proportions between study groups were made using the chi-square test. Cancer-specific (CSS) and overall (OS) survival were determined from date of surgery/radical RT using the Kaplan-Meier technique and comparisons between groups were made using the log-rank test. To account for possible cause of death miscoding, CSS included death from any cancer. Factors associated with treatment choices were evaluated by logistic regression. Factors associated with CSS/OS were evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Use of cystectomy and radical radiotherapy

Between 1994 and 2008 in Ontario, we identified 5259 patients with bladder cancer who underwent curative intent therapy; 3879 (74%) with cystectomy and 1380 (26%) received primary radiotherapy (Table 1). Among those patients treated with cystectomy, there was no difference in rates of preoperative referral to radiation oncology: 10% women (100/974), 9% men (270/2905) (p = 0.371). There was no also no gender difference in the proportion of patients treated with cystectomy: 75% of women (974/1296) versus 73% of men (2905/3963) (p = 0.189). These results were consistent on multivariate analysis controlling for age, comorbidity, socioeconomic status, treatment era, and geographic region.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with bladder cancer treated with cystectomy and radical RT in Ontario 1994–2009 by gender (N = 5259)

| Characteristic | Cystectomy cases (n=3879) | Radical RT cases (n=1380) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Male (n = 2905) | Female (n = 974) | Male (n = 1058) | Female (n = 322) | |

| Patient-related | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| 20–49 | 102 (4%) | 55 (6%) | 18 (2%) | 6 (2%) |

| 50–59 | 346 (12%) | 125 (13%) | 70 (7%) | 19 (6%) |

| 60–69 | 758 (26%) | 221 (23%) | 163 (15%) | 43 (13%) |

| 70–79 | 1167 (40%) | 353 (36%) | 374 (35%) | 102 (32%) |

| 80+ | 532 (18%) | 220 (23%) | 433 (41%) | 152 (47%) |

| SES by quintile* | ||||

| 1 | 557 (19%) | 192 (20%) | 226 (21%) | 78 (24%) |

| 2 | 639 (22%) | 241 (25%) | 261 (25%) | 77 (24%) |

| 3 | 663 (23%) | 200 (21%) | 200 (19%) | 59 (18%) |

| 4 | 560 (19%) | 178 (18%) | 184 (17%) | 52 (16%) |

| 5 | 484 (17%) | 163 (17%) | 183 (17%) | 54 (17%) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 2007 (69%) | 714 (73%) | 544 (51%) | 184 (57%) |

| 1–2 | 740 (25%) | 216 (22%) | 363 (34%) | 116 (36%) |

| 3+ | 158 (5%) | 44 (5%) | 151 (14%) | 22 (7%) |

| Disease-related histology (Ontario Cancer Registry) | ||||

| TCC papillary | 1402 (48%) | 380 (39%) | 515 (49%) | 151 (47%) |

| TCC non-papillary | 1334 (46%) | 483 (50%) | 493 (47%) | 152 (47%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 96 (3%) | 51 (5%) | 32 (3%) | 10 (3%) |

| Squamous carcinoma | 73 (3%) | 60 (6%) | 18 (2%) | 9 (3%) |

| Pathologic T stage¥ | ||||

| <T2 | 570 (20%) | 138 (14%) | N/A | N/A |

| T2 | 640 (22%) | 249 (26%) | N/A | N/A |

| T3 | 1047 (36%) | 415 (43%) | N/A | N/A |

| T4 | 648 (22%) | 172 (18%) | N/A | N/A |

| Pathologic lymph node status¥ | ||||

| NX | 695 (24%) | 310 (32%) | N/A | N/A |

| Node positive | 706 (24%) | 218 (22%) | N/A | N/A |

| Node negative | 1,504 (52%) | 446 (46%) | N/A | N/A |

| LVI | ||||

| No | 778 (27%) | 250 (26%) | N/A | N/A |

| Yes | 1215 (42%) | 433 (44%) | N/A | N/A |

| Unstated | 912 (31%) | 291 (30%) | N/A | N/A |

| Interval from bladder cancer diagnosis to radical treatment | ||||

| 1–6 months | 1680 (58%) | 635 (65%) | 515 (49%) | 183 (57%) |

| 7–12 months | 378 (13%) | 109 (11%) | 207 (20%) | 62 (19%) |

| 12–24 months | 280 (10%) | 78 (8%) | 112 (11%) | 20 (6%) |

| >24 months | 567 (20%) | 152 (16%) | 224 (21%) | 57 (18%) |

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. RT: radiotherapy; SES: socioeconomic status; TCC: transitional cell carcinoma; LVI: lymphovascular invasion; NA: not available; NX: cannot be evaluated.

Quintile 1 represents the communities where the poorest 20% of the Ontario population resided.

T and N stage are pathological stages and based on a review of cystectomy surgical pathology reports. This information was not available for radiotherapy cases.

Extent of disease and management of cystectomy cases

Among the 3879 patients treated with cystectomy, women were more likely than men to have non-urothelial histology (11% vs. 6%, p < 0.001) (Table 1). At the time of cystectomy, women were more likely to have muscle-invasive disease (86% [836/974] vs. 80% [2335/2905], p < 0.001), but less likely to have lymph nodes dissected (68% [664/974] vs. 76% [2210/2905], p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the number of nodes in the surgical specimen by gender. Partial cystectomy rates did not vary between women and men (7% vs. 6%, p = 0.069). Time between diagnosis of bladder cancer and cystectomy was slightly less in women compared to men (65% cystectomy within 6 months vs. 58%, p < 0.001.)

Among the 2944 patients with muscle-invasive urothelial cancer treated with cystectomy, there was no significant difference in use of NACT (5% vs. 4%, p = 0.419) or ACT (18% vs. 20%, p = 0.190) between women and men. Moreover, referral rates to medical oncology before (17% women vs. 18% men, p = 0.678) or after surgery (38% vs. 39%, p = 0.757) did not vary by gender.

Outcomes

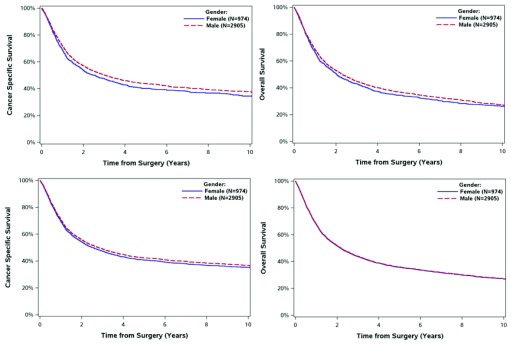

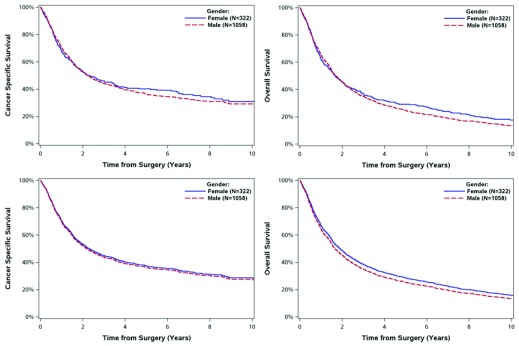

There were no significant differences in postoperative mortality at 30 or 90 days by gender (Table 2). Moreover, OS and CSS at 5 years did not differ by gender among cystectomy cases or radical RT cases. These results were consistent on adjusted analyses (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients with bladder cancer treated with cystectomy and radical RT in Ontario 1994–2009 by gender (N = 5259)

| Characteristic | Cystectomy cases (n=3879) | Radical RT cases (n=1380) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Male (n = 2905) | Female (n = 974) | p value | Male (n = 1058) | Female (n = 322) | p value | |

| 30-day mortality | 77 (3%) | 24 (2%) | 0.752 | N/A | N/A | |

| 90-day mortality | 246 (8%) | 71 (7%) | 0.245 | N/A | N/A | |

| 5-year OS (95% CI) | 37% (35–39%) | 34% (31–37%) | 0.443 | 25% (22–27%) | 29% (24–34%) | 0.291 |

| 5-year CSS (95% CI) | 44% (42–46%) | 40% (37–43%) | 0.075 | 36% (33–40%) | 40% (34–46%) | 0.896 |

| 5-year adjusted OS* | 36% (34–37%) | 36% (33–38%) | 0.896 | 25% (23–28%) | 29% (24–33%) | 0.146 |

| 5-year adjusted CSS* | 42% (41–44%) | 41% (38–43%) | 0.239 | 36% (33–39%) | 37% (32–42%) | 0.695 |

Covariates include: age, socioeconomic status, Charlson comorbidity score, histology, interval from diagnosis to treatment, T stage (cystectomy only), N stage (cystectomy only), LVI: lymphovascular invasion (cystectomy only). RT: radiotherapy; OS: overall survival; CSS: cancer-specific survival; CI: confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Survival of 3879 patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer treated with cystectomy in Ontario 1994–2008 by gender. Panel A: cancer specific survival. Panel B: overall survival. Panel C*: adjusted cancer specific survival. Panel D*: adjusted overall survival. *Covariates adjusted include: age, socioeconomic status, Charlson comorbidity score, histology, interval from diagnosis to treatment, T stage, N stage, lymphovascular invasion.

Fig. 2.

Survival of 1380 patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer treated with radical radiotherapy in Ontario 1994–2008 by gender. Panel A: cancer specific survival. Panel B: overall survival. Panel C*: adjusted cancer specific survival. Panel D*: adjusted overall survival. *Covariates adjusted include: age, socioeconomic status, Charlson comorbidity score, histology, interval from diagnosis to treatment.

Discussion

In this report we explore whether extent of disease, management, and outcomes of patients treated with cystectomy or radical radiotherapy for bladder cancer differ by gender. Several important findings have emerged. First, use of cystectomy or radical radiotherapy did not vary by gender. Second, at time of cystectomy, women were more likely to have muscle-invasive disease. Third, women were less likely to have lymph nodes resected at the time of surgery. Fourth, use of perioperative chemotherapy did not vary by gender. Finally, we did not observe any substantial difference in short-term or long-term outcome between women and men with bladder cancer.

It is worth considering our data within the existing literature. The EUROCARE II study used European registry data from 1985 to 1989 to evaluate differences between men and women in cancer survival.21 In most cancers the survival of women was significantly better than men. A notable exception was bladder cancer, in which the age-standardized 5-year relative survival for women was 60% and 65% for men. While the authors hypothesize that the inferior survival of women might relate to more advanced stage of disease, there are no data included in EUROCARE to test this hypothesis. Fleshner and colleagues described outcomes of 25 197 patients with bladder cancer treated in the United States during the 1985–1988 period.8 The 5-year relative survival of women was worse than men across all stage of disease. Lastly, Mungan and colleagues explored gender differences in outcomes in an American Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cohort of 80 305 patients with bladder cancer diagnosed between 1973 and 1996.9 Five-year relative survival of men was 79.5% and 73.1% in women. Across all stages, the 5-year relative survival of men was superior to women.

The lack of survival difference between women and men observed in our study is not consistent with the studies described above. The reasons for this are not clear, but may relate to the fact that our study was restricted to patients undergoing cystectomy or radical radiotherapy for bladder cancer. As such, while most other studies include all stages of bladder cancer,9,21 including non-invasive disease, our study cohort is restricted to patients with high-risk disease that requires cystectomy or radical RT. Other possible explanations for our discordant results are the fact that other studies do not control for comorbidity or disease-related characteristics.8,9 The results of our study and others8 suggest that women may be more likely to have higher stage cancer. As such, it is important to consider imbalances in stage of disease when comparing outcomes by gender. Finally, the EUROCARE, Fleshner, and Mungan studies describe practice and outcome during the 1970s and 1980s, while our study includes patients treated between 1994 and 2008.8,9,21

Several other studies have investigated differences in treatment practices by gender. Schrag and colleagues described patterns of cystectomy use for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the United States by linking SEER statistics to Medicare data between 1991 and 1999. Among 4664 patients with muscle bladder cancer, women were less likely to undergo cystectomy than their male counterparts (37% vs. 40%, p < 0.04).22 However, these authors did not separate stage of disease between the genders (combined Stages II–IV). In another review of treatment patterns in the United States between 1992 and 1999, Konety and colleagues found that use of cystectomy or RT for stage II and III bladder cancer did not differ by gender when results were adjusted for extent of disease.23 These data are consistent with our finding that use of cystectomy/RT did not differ between women and men. Moreover, our study did not find any gender difference in use of perioperative chemotherapy for bladder cancer.

Our study confirms, but does not provide any insight into, why bladder cancer is 3 times more common in men. Historically it was thought that excessive exposure to occupational chemicals and higher rates of cigarette smoking were responsible for this gender difference; however, recent evidence suggests that even after controlling for these factors the incidence remains higher in men.3 Some more recent literature has suggested that androgen receptor signals are involved in bladder cancer development24 and that androgen deprivation therapy can prolong recurrence-free survival in bladder cancer.25 However, the reason for the striking gender difference in disease incidence remains uncertain.

This study is the most current and comprehensive analysis of gender differences in extent of disease, treatment, and outcome of bladder cancer. However, several limitations merit comment. As with all observational studies there is the potential for the results to be biased by unmeasured prognostic factors. Moreover, we are only partially able to control for known patient variables, such as comorbidity. More importantly, the lack of information about stage of disease for RT cases makes it difficult to fully interpret the adjusted survival analyses. Pathology reports from pre-RT transurethral resection specimens were not available and is there a gender effect in bladder cancer? therefore we were no able to identify which RT cases did not have muscle-invasive disease. Moreover, our analysis is restricted to those patients treated with cystectomy or radical RT. As such, patients with early-stage superficial disease and advanced metastatic disease were not included in this analysis. Despite these limitations, in addition to the very large sample size, a major strength of the current study is the fact that by virtue of the Ontario Cancer Registry, our study population includes all cases of bladder cancer treated with curative intent within Ontario and is therefore unselected; this minimizes referral and selection biases that affect traditional institution-based observational studies.26,27

Conclusion

We have found that although bladder cancer is more common in men, there was no substantial gender difference in the extent of the disease, treatment, or outcome among patients treated with cystectomy or radical radiotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this material are based on data and information provided by Cancer Care Ontario. However, the analysis, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Cancer Care Ontario. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors all declare no competing financial or personal interests. This work was supported by Cancer Care Ontario and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. Dr. Booth is supported as a Canada Research Chair in Population Cancer Care.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Statistics CCSACOC Canadian Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Society. 2014;2014:1–132. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Skipper PL, et al. Gender- and smoking-related bladder cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:538–45. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.7.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman ND, Silverman DT, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Association between smoking and risk of bladder cancer among men and women. JAMA. 2011;306:737–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaertner RRW, Trpeski L, Johnson KC, Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group. A case-control study of occupational risk factors for bladder cancer in Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:1007–19. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto H, Yang Z, Chen Y-T, et al. Promotion of bladder cancer development and progression by androgen receptor signals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:558–68. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cárdenas-Turanzas M, Cooksley C, Pettaway CA, et al. Comparative outcomes of bladder cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:169–75. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000223885.25192.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Underwood W, Dunn RL, Williams C, et al. Gender and geographic influence on the racial disparity in bladder cancer mortality in the US. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleshner NE, Herr HW, Stewart AK, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on bladder carcinoma. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1996;78:1505–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961001)78:7<1505::AIDCNCR19>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mungan NA, Aben KK, Schoenberg MP, et al. Gender differences in stage-adjusted bladder cancer survival. Urology. 2000;55:876–80. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch M, McPhee MS, Gaedke H, et al. Five year follow-up of patients with cancer of the bladder--the Northern Alberta experience. Clin Invest Med. 1988;11:253–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson EK, Daignault S, Zhang Y, et al. Patterns of hematuria referral to urologists: Does a gender disparity exist? Urology. 2008;72:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May M, Stief C, Brookman-May S, et al. Gender-dependent cancer-specific survival following radical cystectomy. World J Urol. 2011;30:707–13. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0773-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth CM, Siemens DR, Li G, et al. Curative therapy for bladder cancer in routine clinical practice: A population-based outcomes study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26:506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booth CM, Siemens DR, Li G, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A population-based outcomes study. Cancer. 2014;120:1630–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke EA, Marrett LD, Kreiger N. Cancer registration in Ontario: A computer approach. IARC Sci Publ. 1991:246–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd C, Zhang-Salomons JY, Groome PA, et al. Associations between community income and cancer survival in Ontario, Canada, and the United States. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2244–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goel V. The ICES Practice Atlas. 2nd ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kankesan J, Shepherd FA, Peng Y, et al. Factors associated with referral to medical oncology and subsequent use of adjuvant chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: A population-based study. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:30–7. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Booth CM, Siemens DR, Peng Y, et al. Patterns of referral for perioperative chemotherapy among patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A population-based study. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:1200–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micheli A, Mariotto A, Giorgi Rossi A, et al. The prognostic role of gender in survival of adult cancer patients. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2271–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrag D, Mitra N, Xu F, et al. Cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Patterns and outcomes of care in the medicare population. Urology. 2005;65:1118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konety BR, Joslyn SA. Factors influencing aggressive therapy for bladder cancer: An analysis of data from the SEER program. J Urol. 2003;170:1765–71. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091620.86778.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu J-W, Hsu I, Xu D, et al. Decreased tumorigenesis and mortality from bladder cancer in mice lacking urothelial androgen receptor. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1811–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izumi K, Taguri M, Miyamoto H, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy prevents bladder cancer recurrence. Oncotarget. 2014;5:12665–74. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Booth CM, Tannock IF. Randomised controlled trials and population-based observational research: Partners in the evolution of medical evidence. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:551–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Booth CM, Mackillop WJ. Translating new medical therapies into societal benefit: The role of population-based outcome studies. JAMA. 2008;300:2177–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.18.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]