Abstract

The recent 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults from the Eight Joint National Committee Panel may significantly impact the aging US population. We performed a cross-sectional analysis of black and white participants in ARIC who participated in the 5th study visit (2011–2013). Sitting blood pressure was calculated from the average of 3 successive readings taken after a 5-minute rest. Currently prescribed antihypertensive medications were recorded by reviewing medication containers brought to the visit. Blood pressure control was defined using both the 7th and 8th Joint National Committee thresholds. Of 6,088 participants (mean age 75.6 years [range 66–90], 58.4% female, 23.2% African American), 54.9% had either diabetes or chronic kidney disease. The prevalence of hypertension according to 7th Joint National Committee thresholds was 81.9%, and 62.8% of the entire sample were at blood pressure goal. Using the 8th Joint National Committee thresholds, 79.4% were at blood pressure goal (16.6% were reclassified as at goal). Reclassification was higher for individuals with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (20.6%) compared to individuals without either condition (11.6%). Use of antihypertensive medications in our cohort was high, with 75.0% prescribed at least one antihypertensive medication and 46.7% on 2 or more antihypertensive agents. In conclusion, in a US cohort of aging white and black individuals, approximately 1 in 6 individuals were reclassified as having blood pressure at goal by 8th Joint National Committee guidelines. Despite these less aggressive goals, over 20% remain uncontrolled by the new criteria.

Keywords: Hypertension, Blood Pressure, Guidelines, Antihypertensive Medications, Epidemiology

Introduction

Approximately one-third of the US adult population has hypertension.1 The prior Seventh Joint National Committee Guidelines on Prevention, Evaluation, Detection, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) established treatment goals for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of <130/80 mmHg for individuals with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (CKD) and <140/90 mmHg for individuals without these comorbidities.2 The recently released 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults from the Eight Joint National Committee Panel (JNC8P) guidelines endorsed lifestyle modifications to reduce blood pressure (BP) but largely focused on BP thresholds for pharmacologic treatment. After a critical review of the evidence, the JNC8P guidelines established less stringent thresholds for consideration of pharmacologic intervention, setting a goal BP of < 150/90 mmHg for aging individuals (≥ 60 years) without diabetes or CKD, and < 140/90 mmHg for individuals with diabetes, CKD, or age < 60 years.3

A recent analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that, compared to JNC7, application of JNC8P guidelines would substantially increase the number of adults who would now be considered at goal BP, mainly due to reclassification of older individuals with a SBP 140–149 mmHg.4 The implications of JNC8P for aging adults warrant further analysis, especially considering that older adults have a high prevalence of hypertension and are at high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), but also may be prone to medication side effects or serious adverse events related to treatment, such as falls.5 The aim of this study was to contrast the prevalence of BP control between the JNC7 and JNC8P guidelines and to analyze the use of antihypertensive medications in aging black and white individuals in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. This information will help quantify potential impact of implementation of the new guidelines and provide a contemporary estimate of the prevalence of antihypertensive medication use in a community-based sample of aging adults.

Methods

Study Design and Population

ARIC is a longitudinal study of cardiovascular disease sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The ARIC cohort was selected in 1987–89 as a probability sample of 15,792 men and women initially aged 45–64 years at 4 study centers in the United States. Three of the sites (Washington County, MD, Forsyth County, NC, and selected suburbs of Minneapolis, MN) enrolled community-representative samples while the 4th site (Jackson, MS) sampled African Americans only. Details of the sampling, study design, and cohort examination procedures have been previously published.6 Eligible participants were interviewed at home and then underwent a baseline clinical examination conducted in 1987–1989. Four follow-up examinations were conducted including the most recent during 2011–2013 (ARIC visit 5). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating universities, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Of 10,036 original cohort members who were still alive, 6,538 took part in visit 5 (response rate 65%). We excluded, due to small numbers, individuals who were of a racial/ethnic group other than white or black, as well as nonwhites in the Minneapolis and Washington County field centers (n=41). We also excluded 409 participants who were missing covariates, creating a study sample of 6,088 participants.

Blood Pressure Measurement, Antihypertensive Medications, and Blood Pressure Goals

Sitting BP was obtained 3 times in succession after a 5-minute rest using an automated sphygmomanometer and an average of the 3 readings was used. Currently prescribed antihypertensive medications were recorded by reviewing medication containers brought by the participant to visit 5. Of the 6,088 participants, only 125 did not bring medications to the visit, 73 of whom reported not taking any medications. Of the 52 remaining individuals, 39 were successfully contacted and their medications recorded via telephone interview. Beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, diuretics, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ACE-i/ARB), were considered the main classes of antihypertensive medications. Hydralazine, clonidine, and alpha-blockers were included as “other” antihypertensive medications. Control of BP was analyzed according to both JNC7 and JNC8P guidelines2,3. JNC7 guidelines targeted a BP of <130/80 mmHg and <140/90 mmHg for individuals with and without diabetes or CKD. JNC8P guidelines recommend a goal blood pressure of <150/90 mmHg for individuals aged >60 years (our entire sample was >60 years old) and a goal blood pressure of <140/90 mmHg for individuals with diabetes or CKD. The JNC8P guidelines state that there are limited data for individuals with CKD who are >70 years old, and thus this BP goal does not strictly apply to these individuals and therefore individual patient preference, goals of care, and clinical judgment should be used.

Diabetes, CKD, and Other Covariates

Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood sugar ≥ 126 mg/dL, use of a diabetic medication, a non-fasting glucose of ≥ 200 mg/dL, or self-reported diagnosis of diabetes by a physician. CKD was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 based on measured creatinine and cystatin-C, calculated using the CKD epidemiology collaboration equation (over 20% of the validation sample for this equation were > 65 years).7

Age, ethnicity, sex, education level, and cigarette smoking status were obtained using standardized questionnaires administered by trained and certified interviewers. Awareness of hypertension was queried by asking if a health professional had told the participant that he or she had high blood pressure. Height and weight were recorded by trained personnel. Body Mass Index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Prevalent CVD was defined as CHD, myocardial infarction, stroke, or peripheral arterial disease prior to visit 5. Incident cases of CVD since baseline (except for peripheral arterial disease) have been reviewed by the ARIC Morbidity and Mortality Classification Committee.

Blood samples were collected after a requested fast of at least 8 hours into EDTA tubes and processed at the field centers. Plasma aliquots were frozen at −80 deg C and sent for analysis at the ARIC Atherosclerosis Clinical Research Laboratory at Baylor College of Medicine. Total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were determined by enzymatic methods on a Beckman Coulter AU480 auto-analyzer (Olympus Corporation). LDL-C was calculated by the Friedewald equation in those with triglyceride levels < 400 mg/dL.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics at visit 5 were analyzed overall as well as stratified by prevalent diabetes or CKD status. Categorical variables are presented as n (%) and continuous variables as mean (SD). We analyzed the prevalence of control of blood pressure according to both JNC7 and JNC8P guidelines for the overall sample and stratified by prevalent diabetes or CKD. We then calculated the percent of individuals at different BP thresholds stratified by diabetes or CKD. We also performed stratified analyses according to race and gender.

Finally, we calculated the prevalence of antihypertensive medication use, in total as well as according to individual antihypertensive classes, for the total ARIC visit 5 sample and according to race. All statistical analysis were carried out using SAS 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The mean age of the 6,088 ARIC participants in 2011–13 was 75.6 (5.2) years (range 66 to 90), 3,555 (58.4%) were female, and 1,412 (23.2%) were black. The prevalence of diabetes and/or CKD was high (54.9%). The baseline characteristics of the overall sample as well as stratified by the presence of diabetes or CKD are shown in Table 1. Participants were unlikely to be current smokers (5.7%) and had a relatively high prevalence of aspirin (68.3%) and statin (51.1%) utilization.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 6,088 participants of the 5th visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 2011–13

| Characteristic* | All (n=6088) | No DM/CKD (n=2744) | DM/CKD (n=3344) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 75.6 (5.2) | 74.5 (4.7) | 76.4 (5.4) |

| Female, % | 58.4 | 59.8 | 57.2 |

| Black, % | 23.2 | 21.1 | 24.9 |

| High school graduate, % | 85.7 | 90.0 | 82.3 |

| Current smoker, % | 5.7 | 6.5 | 5.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.7 (5.7) | 27.4 (5.3) | 29.7 (5.9) |

| Cardiovascular Disease, % | 29.9 | 21.3 | 37.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 130.4 (18.3) | 129.7 (16.9) | 131.1 (19.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 66.7 (10.7) | 67.8 (10.2) | 65.8 (11.0) |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 180.9 (41.7) | 188.7 (39.8) | 174.4 (42.1) |

| HDL, mg/dL | 52.2 (14.0) | 55.6 (14.3) | 49.4 (13.1) |

| LDL, mg/dL | 104.2 (34.7) | 110.8 (33.0) | 98.8 (35.2) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 123.1 (56.2) | 112.8 (48.5) | 131.6 (60.5) |

| Aspirin, % | 68.3 | 64.0 | 71.8 |

| Statin use, % | 51.1 | 42.4 | 58.3 |

| Other lipid medication, % | 4.7 | 3.8 | 5.5 |

Values are mean (SD) or % prevalence

The prevalence and awareness of hypertension according to JNC7 and blood pressure classification and treatment rates according to JNC7 and JNC8P guidelines for the entire sample are shown in Table 2. According to JNC7 guidelines, 81.9% of our sample had hypertension and 80.9% of those with hypertension were aware of the diagnosis. Of the total sample, 62.8% had blood pressure that was at goal (71.2% of whom were using antihypertensive medications). In contrast, 79.4% of our total sample was at BP goal according to JNC8P criteria (72.7% of whom were using antihypertensive medications). Therefore, 16.6%, approximately 1 in 6, were reclassified by JNC8P criteria for BP control. In individuals without diabetes or CKD, 11.6% were at BP goal by JNC8P but not JNC7. The rate of reclassification was higher for individuals with diabetes or CKD, with 20.6% at BP goal according to JNC8P but not JNC7 (Table 2).

Table 2.

The prevalence and awareness of hypertension according to the 7th Joint National Committee and blood pressure classification and treatment rates according to the 7th and 8th Joint National Committee guidelines for the treatment of high blood pressure in 6,088 participants from the 5th visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 2011–13.

| Total Sample | JNC7 Guidelines | JNC8P Guidelines | Reclassified by JNC8P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=6,088) | |||

| Prevalence (% of n) | 4986 (81.9) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 4035 (80.9) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 3822 (62.8) | 4,831 (79.4) | 1,009 (16.6) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 2720 (71.2) | 3514 (72.7) | 794 (78.7) |

|

| |||

| No Diabetes or CKD (n=2,744) | Goal <140/90 | Goal <150/90 | |

| Prevalence (% of n) | 1898 (69.2) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 1467 (77.3) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 2,106 (76.8) | 2,424 (88.3) | 318 (11.6) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 1260 (59.8) | 1465 (60.4) | 205 (64.5) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes or CKD (n=3,344) | Goal <130/80 | Goal <140/90 | |

| Prevalence (% of n) | 3088 (92.3) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 2568 (83.2) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 1,716 (51.3) | 2,407 (72.0) | 691 (20.6) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 1460 (85.1) | 2049 (85.1) | 589 (85.2) |

Abbreviations: JNC – Joint National Committee, CKD – Chronic Kidney Disease, BP – Blood Pressure

Percentage of the number with hypertension

Percentage of the number at goal BP

The JNC8P guidelines do not address definitions of hypertension and had not yet been released at the time of data collection so the prevalence and awareness of hypertension according to JNC8P was not analyzed

Taking the recommended age thresholds into account further increased the prevalence of being at goal according to JNC8P. Assuming a goal BP of <150/90 mmHg for individuals with CKD but age ≥ 70 years resulted in an additional 289 individuals (4.7% of the total sample) being considered at goal. Thus, applying the strict age cut-off for the <140/90 mmHg CKD recommendation, 21.3% of our sample would be reclassified as at goal by JNC8P compared to JNC7. The prevalence of control according to different BP thresholds by CKD and diabetes status is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of sex, race, and antihypertensive medication use, and the prevalences of blood pressure classification according to different thresholds stratified by the presence of diabetes and chronic kidney disease in 6,088 participants from the 5th visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 2011–13.

| Characteristic/Threshold met | Diabetes | CKD | Diabetes or CKD | No diabetes or CKD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1926 | 2256 | 3344 | 2744 |

| Characteristic | ||||

| Female, % | 1049 (54.5%) | 1344 (59.6%) | 1913 (57.2%) | 1641 (59.8%) |

| Black, % | 584 (30.3%) | 486 (21.5%) | 833 (24.9%) | 579 (21.2%) |

| On medication, % | 1737 (90.2%) | 1934 (85.7%) | 2883 (86.2%) | 1684 (61.4%) |

| Threshold met | ||||

| BP < 130/80 | 970 (50.4%) | 1170 (51.9%) | 1716 (51.3%) | 1491 (54.3%) |

| BP < 130/90 | 987 (51.3%) | 1182 (52.4%) | 1740 (52.0%) | 1512 (55.1%) |

| BP < 140/80 | 1359 (70.6%) | 1563 (69.3%) | 2341 (70.0%) | 2023 (73.7%) |

| BP < 140/90 | 1400 (72.7%) | 1602 (71.0%) | 2407 (72.0%) | 2106 (76.8%) |

| BP < 150/90 | 1665 (86.5%) | 1902 (84.3%) | 2857 (85.4%) | 2424 (88.3%) |

Abbreviations: CKD – Chronic Kidney Disease, BP – Blood Pressure

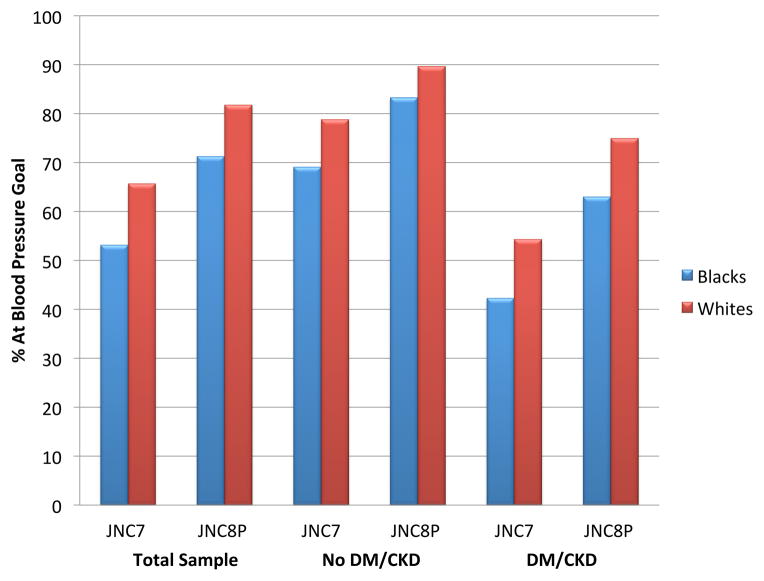

Blacks were more likely to have hypertension as defined by JNC7 and less likely to be at BP goal by either guideline compared to whites (Table 4, Figure 1). According to JNC8P criteria, 81.8% of whites were at BP goal compared to 71.3% of blacks. Although the prevalence of BP control differed between races, the reclassification rate between JNC7 and JNC8P in whites and black was similar (Table 4). An analysis stratified by gender showed generally similar rates of control and reclassification for men and women (results not shown).

Table 4.

The prevalence and awareness of hypertension according to the 7th Joint National Committee blood pressure classification and treatment rates according to the 7th and 8th Joint National Committee guidelines for the treatment of high blood pressure according to race in 6,088 participants from the 5th visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 2011–13.

| Whites | JNC 7 Guidelines | JNC8P Guidelines | Reclassified to at goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=4,676) | |||

| Prevalence (% of n) | 3696 (79.0) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 2874 (77.6) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 3,070 (65.7) | 3824 (81.8) | 754 (16.1) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 2090 (68.1) | 2655 (69.4) | 565 (74.9) |

|

| |||

| No Diabetes or CKD (n=2,165) | Goal <140/90 | Goal <150/90 | |

| Prevalence (% of n) | 1410 (65.1) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 1040 (73.8) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 1,706 (78.8) | 1,942 (89.7) | 236 (10.9) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 951 (55.7) | 1087 (56.0) | 136 (57.6) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes or CKD (n=2,511) | Goal <130/80 | Goal <140/90 | |

| Prevalence (% of n) | 2286 (91.0) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 1834 (80.2) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 1,364 (54.3) | 1,882 (75.0) | 518 (20.6) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 1139 (83.5) | 1568 (83.3) | 429 (82.8) |

|

| |||

| Blacks | JNC 7 Guidelines | JNC8P Guidelines | Reclassified to at goal |

|

| |||

| Overall (n=1,412) | |||

| Prevalence (% of n) | 1290 (91.4) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 1161 (90.0) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 752 (53.2) | 1,007 (71.3) | 255 (18.1) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 630 (83.8) | 859 (85.3) | 229 (89.8) |

|

| |||

| No Diabetes or CKD (n=579) | Goal <140/90 | Goal <150/90 | |

| Prevalence (% of n) | 488 (84.3) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 427 (87.5) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 400 (69.1) | 482 (83.3) | 82 (14.2) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 309 (77.3) | 378 (78.4) | 69 (84.2) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes or CKD (n=833) | Goal <130/80 | Goal <140/90 | |

| Prevalence (% of n) | 802 (96.3) | ‡ | |

| Awareness (%*) | 734 (91.5) | ‡ | |

| At Goal BP (% of n) | 352 (42.3) | 525 (63.0) | 173 (20.8) |

| On BP Medications (%†) | 321 (91.2) | 481 (91.6) | 160 (92.5) |

Abbreviations: JNC – Joint National Committee, CKD – Chronic Kidney Disease, BP – Blood Pressure

Percentage of the number with hypertension

Percentage of the number at goal BP

The JNC8P guidelines do not address definitions of hypertension and had not yet been released at the time of data collection so the prevalence and awareness of hypertension according to JNC8P was not analyzed.

Figure 1.

The Prevalence of At-Goal Blood Pressure according to JNC7 and JNC8P blood pressure guidelines in black and white individuals stratified by diabetes or chronic kidney disease in 6,088 participants from the 5th visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 2011–13.

Abbreviations: JNC7 – 7th Joint National Committee, JNC8P – 8th Joint National Committee Panel, DM – Diabetes Mellitus, CKD – Chronic Kidney Disease

Finally, 75.0% of our sample had a filled prescription for at least one antihypertensive medication, 46.7% ≥ 2 antihypertensive agents, and 18.5% ≥ 3 agents (Table 5). A breakdown of antihypertensive medications according to classes showed that ACE/ARB was the most frequently prescribed class (46.4%), including use in 56.3% of black participants (Table 5).

Table 5.

The prevalence of antihypertensive medication use, and use of specific antihypertensive classes in 6,088 participants from the 5th visit of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 2011–13.

| Antihypertensive Medication | All (n=6,088) | Whites (n=4,676) | Blacks (n=1,412) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Antihypertensive, % | 4567 (75.0) | 3331 (71.2) | 1236 (87.5) |

| ≥ 2 Antihypertensives, % | 2841 (46.7) | 1953 (41.8) | 888 (62.9) |

| ≥ 3 Antihypertensives, % | 1129 (18.5) | 746 (16.0) | 382 (27.1) |

|

| |||

| ACE-Inhibitor or ARB, % | 2822 (46.4) | 2027 (43.4) | 795 (56.3) |

| Calcium Channel Blocker, % | 1423 (23.3) | 887 (19.0) | 536 (38.0) |

| Diuretic, % | 1971 (32.4) | 1296 (27.7) | 675 (47.8) |

| Beta-Blocker, % | 2079 (34.2) | 1662 (35.5) | 417 (29.5) |

| Other* | 548 (9.0) | 364 (7.8) | 184 3.0) |

Abbreviations ACE – Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ARB – Angiotensin Receptor Blocker.

Other antihypertensive medications include: Hydralazine, Clonidine, and Alpha-blockers

Discussion

In the ARIC sample of aging community dwelling adults, approximately 1 out of 6 individuals who previously would have been considered to have uncontrolled blood pressure by JNC7 criteria would now be considered to be at BP goal according to JNC8P recommendations, including 20% and 10% of individuals with and without diabetes or CKD respectively. Black individuals were less likely to be at BP goal compared to whites but rates of JNC8P reclassification were similar in both races.

Additionally, we found the prevalence of hypertension in our aging sample to be high (80%), concordant with data from the Framingham Heart Study that found a 90% lifetime risk of developing hypertension in individuals age 55–65 years.8 Despite a high prevalence of antihypertensive medication use (75%) and more lenient goals, approximately 20% of the total sample had BP that remained not at goal according to JNC8P. Whether this high rate of uncontrolled hypertension is due to lack of awareness, treatment inertia, medication non-adherence, or other causes is unclear. Regardless, further efforts aimed at improving detection and control of hypertension in aging individuals remain warranted.

Our results are concordant with recent data from NHANES that described a younger sample of 16,372 US adults4. Approximately 1/3 of the NHANES sample was > 60 years old with 58.7% and 79.1% of these individuals meeting the JNC7 and JNC8P BP goals, respectively (20.4% were reclassified assuming a strict age cut-off at age 70 for individuals with CKD). The same NHANES study also reported a 25.8% increase in “at goal” BP in individuals with treatment-eligible hypertension > 60 years old with application of JNC8P. This may appear larger than the 16.6% we report in this study but the NHANES study analyzed achievement of goal BP only in those individuals with treatment eligible hypertension (on antihypertensive meds or BP not at goal). Given that some individuals may have achieved goal BP with lifestyle interventions, we chose to analyze at goal BP for the entire sample. When the different denominators are taken into account, our results are very similar to the NHANES study.

Concern has been raised that implementation of JNC8P guidelines will adversely affect the elderly population due to less aggressive treatment of hypertension leading to an increase in CVD events.9 The decision to raise the goal blood pressure to <150/90 mmHg for individuals ≥ 60 years old was based on data from multiple randomized trials data showing a clear reduction in CVD events for individuals with hypertension treated to a goal BP of <150/90 mmHg, 10–12 with two subsequent trials being unable to show a reduction in CVD events by targeting a more aggressive goal BP of <140/90 compared to <150/90.13,14 The JNC8P committee does acknowledge that the two existing trials were underpowered, therefore providing only low quality evidence, and the panel did not reach a consensus on this decision.15

A recent meta-analysis suggested that, similar to the recently released cholesterol guidelines,16 absolute CVD risk could potentially be used to target populations most likely to benefit from antihypertensive treatment.17 Given that age is the dominant risk factor in traditional CVD risk models, more aggressive treatment of hypertension in the elderly may produce a larger absolute benefit compared to treatment of younger individuals. Recent data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry PINNACLE Registry suggests that the individuals reclassified by JNC8P are at high absolute risk, with average 10-year CVD risk of almost 30%.18 The JNC8P guidelines do state that for individuals on antihypertensive medications who achieve a BP of < 140/90 mm Hg, their antihypertensive medication regimen does not need to be reduced.

The decision to increase the goal BP for individuals with CKD or diabetes was largely based on randomized trials that failed to demonstrate a significant reduction in CVD in these populations by targeting more aggressive BP treatment goals. In patients with CKD, 3 separate randomized trials have failed to show an improvement in renal or CVD outcomes by targeting more aggressive BP goals.19–21 For individuals with diabetes, the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) hypertension trial evaluated the effect of targeting a goal SBP of <120 mmHg (compared to <140mmHg) on cardiovascular outcomes. Despite achieving the targeted BP in the intervention group (mean SBP 119.3 mm Hg compared to 133.5 mm Hg in the control group), the composite end-point of myocardial infarction, stroke, and CVD death was not significant reduced, though there was a significant reduction in stroke, a pre-specified secondary end-point.22

Black participants in our study were less likely to be at goal compared to whites despite higher rates of antihypertensive medication use. This is consistent with prior data showing an increased frequency in the prevalence of hypertension in the US African-American population.23 Given the increased prevalence of hypertension in black individuals, concern has been raised that the less aggressive JNC8P guidelines will disproportionately have a negative effect on the black population.6 Interestingly, ACE-inhibitor/ARB was the most commonly used antihypertensive class in both whites and blacks, despite the fact that both JNC7 and JNC8P recommend use of a diuretic or calcium-channel blocker first in black populations due a frequent low renin state leading to a diminished response to renin-angiotensin inhibition, although the high rate of diabetes and CKD in black participants would provide an alternative indication for ACE-inhibitor/ARB use.

Our study has several strengths, including a large sample of black and white men and women, a contemporary analysis of currently prescribed antihypertensive medications, including specific antihypertensive classes, and carefully collected data on CVD risk factors as well as CVD diagnoses. It also has potential limitations. Alternative indications for specific antihypertensive medications (such as beta-blockers for atrial fibrillation or ACE-i/ARB for systolic heart failure), a history of adverse effects from antihypertensive therapy, patient preferences, and other factors that would influence antihypertensive usage rates could not be assessed. Additionally, medication adherence was not assessed. We applied JNC8P criteria to our sample without information on BP levels at the time of initiation of therapy, making it difficult to determine whether evidence based guidelines were being followed. The presence of uncontrolled obstructive sleep apnea syndrome was not assessed at ARIC visit 5 and may have partially contributed to the high rates of uncontrolled hypertension seen in our study. The ARIC cohort was recruited over 25 years ago and at that time was quite representative of the source communities. Yet, the blacks were from one community (Jackson, MS) and the whites from 3 others, so the sample was not representative of the entire US. Over time, there has been attrition due to death, emigration from the communities, and dropouts. Nevertheless, those who died before reaching old age would never be included in any sample of the elderly. Among those who were still alive at the time of visit 5, we were able to examine 65%, which is a response rate that compares favorably with NHANES surveys.

Perspective

Concern has been raised that the recent 2014 JNC8 blood pressure guidelines may lead to under treatment of hypertension in older individuals and those with diabetes and CKD due to more lenient blood pressure goals. Our findings do suggest that implementation of the JNC8 guidelines could result in a substantial reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications in older adults, especially in individuals with diabetes or CKD. Our results suggest approximately 1 in 6 older adults would be reclassified as “at goal” under the new JNC8 guidelines. Despite a high prevalence of antihypertensive medication use (~75%) and more lenient goals, over 20% of this older cohort remained above JNC8 goals, indicating a continued need for efforts aimed at better detection and control of hypertension. Further research is also needed to determine the true impact of these guidelines on the rate of antihypertensive medications use and subsequent CVD outcomes.

Novelty and Significance.

What is New?

Our study is the first to focus on the impact of JNC8P on the aging US population.

What is Relevant?

Concern has been raised that the recent 2014 JNC8P blood pressure guidelines may lead to under treatment of hypertension in aging individuals and those with diabetes and CKD due to more lenient blood pressure goals.

Summary

Compared to JNC7 guidelines, approximately 1 in 6 aging adults would be reclassified as having “at goal” blood pressure under the new JNC8P guidelines.

Rates of reclassification were similar between black and white individuals though black individuals were less likely to have blood pressure at goal by either guideline.

Despite a high prevalence of antihypertensive medication use (~75%) and more lenient goals, over 20% of this aging cohort remained above JNC8P goals, indicating a continued need for efforts aimed at better detection and control of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C).

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors of this manuscript have no disclosures in relationship to this study.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2015 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navar-Boggan AM, Pencina MJ, Williams K, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED. Proportion of US adults potentially affected by the 2014 hypertension guideline. JAMA. 2014;311:1424–1429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, McAvay GJ, Peduzzi P, Gross CP, Zhou B, Lin H. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:588–595. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ARIC Investigators. The atherosclerosis risk in the communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS CKD-EPI Investigators. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:20–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Larson MG, Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB, Levy D. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1003–1010. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.8.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakoff LR, Gillespie RL, Ferdinand KC, Fergus IV, Akinboboye O, Williams KA, Walsh MN, Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ. 2014 Hypertension Recommendations From the Eighth Joint National Committee Panel Members Raise Concerns for Elderly Black and Female Populations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or aging. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350:757–764. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS) Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115–2127. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimamoto K, Shimada K, Imai Y, Kikuchi K, Ito S, Eto T, Kimura G, Imaizumi T, Takishita S, Ueshima H. Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study Group. Hypertension. 2010;56:196–202. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright JT, Jr, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150mmHg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:499–503. doi: 10.7326/M13-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Sundström J, Arima H, Woodward M, Jackson R, Karmali K, Lloyd-Jones D, Baigent C, Emberson J, Rahimi K, MacMahon S, Patel A, Perkovic V, Turnbull F, Neal B. Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2014;384:591–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borden WB, Maddox TM, Tang F, Rumsfeld JS, Oetgen WJ, Mullen JB, Spinler SA, Peterson ED, Masoudi FA. Impact of the 2014 Expert Panel Recommendations for Management of High Blood Pressure on Contemporary Cardiovascular Practice: Insights From the NCDR PINNACLE Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2196–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G, et al. REIN-2 Study Group. Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with non-diabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:939–946. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright JT, Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al. African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group. . Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–2431. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:877–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ACCORD Study Group. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]