Abstract

Electrical carotid baroreflex activation has been used to treat patients with resistant hypertension. It is hypothesized that, in conscious rats, combined activation of carotid baro- and chemoreceptors afferences attenuates the reflex hypotension. Rats were divided into 4 groups: 1) control group, with unilateral denervation of the right carotid chemoreceptors; 2) chemoreceptor denervation group, with bilateral ligation of the carotid body artery; 3) baroreceptor denervation group, with unilateral denervation of the left carotid baroreceptors and right carotid chemoreceptors; 4) carotid bifurcation denervation group, with denervation of the left carotid baroreceptors and chemoreceptors, plus denervation of the right carotid chemoreceptors. Animals were subjected to 4 rounds of electrical stimulation (5 V, 1 ms), with 15 Hz, 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz applied randomly for 20 s. Electrical stimulation caused greater hypotensive responses in the chemoreceptor denervation group than in the control group, at 60 Hz (−37 mmHg vs −19 mmHg) and 90 Hz (−33 mmHg vs −19 mmHg). The baroreceptor denervation group showed hypertensive responses at all frequencies of stimulation. In contrast, the carotid sinus denervation group showed no hemodynamic responses. The control group presented no changes in heart rate, whereas the chemoreceptor denervation group and the baroreceptor denervation group showed bradycardic responses. These data demonstrate that carotid chemoreceptor activation attenuates the reflex hypotension caused by combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats. These findings may provide useful insight for clinical studies using Baroreflex Activation Therapy in resistant hypertension and/or heart failure.

Keywords: Baroreflex, hemodynamics, hypertension, pressoreceptors, sympathetic nervous system

Introduction

Electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus has been used recently in clinical trials to treat hypertensive patients resistant to pharmacological therapy.1,2 The rationale for supporting this approach is that electrical activation of the carotid baroreflex leads to activation of the cardiac parasympathetic drive and inhibition of sympathetic activity to the heart and peripheral vessels.3 More recently, electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus has emerged as a therapeutic tool in the management of heart failure as well.4–6

During electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus in patients with resistant hypertension1,2 or with heart failure,4–6 the anatomical position of the carotid body may allow undesirable activation of the carotid chemoreceptors, a possibility raised by Zucker and colleagues7 and based on studies in dogs with heart failure. It is well known that activation of chemoreceptors produces an increase in arterial pressure (sympathetic activation) and bradycardia (parasympathetic activation), as well as conspicuous ventilatory responses.8,9

Recently, an important role for carotid body chemoreceptors in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease has been suggested.10,11 Studies of carotid body de-afferentation in rabbits12 and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR)10 have demonstrated that removal of the carotid bodies is an effective means for sustained sympathoinhibition10,12 and may be considered as a therapeutic option, possibly transferable to humans for reduction of sympathetic drive, disordered breathing patterns, and incidence of arrhythmia in heart failure.12 Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the cardiocirculatory effects triggered by attendant chemoreflex activation during Baroreflex Activation Therapy (BAT)13,14 could potentially interfere with the classical hemodynamic response (hypotension and bradycardia) caused by the activation of the baroreflex.15. Of note, the recent study from Alnima and colleagues,16 using short-term electric activation settings of 2 and 4 min, provided remarkable information for BAT using the Rheos system. These authors observed that this electroceutical therapy in patients with resistant hypertension did not stimulate respiration at several electric device activation parameters suggesting that there is no attendant activation of carotid body chemoreceptors during device therapy.16

In our laboratory, studies on short-term electrical stimulation of the aortic depressor nerve in conscious normotensive17 or hypertensive18 rats have provided important information regarding the autonomic regulation of arterial pressure and heart rate (HR) by the aortic baroreflex. In the current study, the methodological procedure for stimulating the aortic depressor nerve in conscious rats17,18 was adapted to stimulate the carotid sinus. Thus, simultaneous electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats was combined with surgical procedures for the selective denervation of the carotid chemo-8,19 and baroreceptors (unpublished data) to investigate the role played by the peripheral (carotid body) chemoreflex during combined electrical activation of the carotid sinus and carotid sinus nerve.

The aim of the current study was to investigate whether the attendant activation of carotid chemoreceptor afferents attenuates the reflex hypotension caused by combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats. To accomplish this, an experimental model with selective denervation of carotid chemo-8,19 and/or baroreceptors (unpublished data) in rats was used. By means of this experimental approach, it was possible to examine the relative contribution of both baroreceptors and chemoreceptors on the hemodynamic parameters of arterial pressure and HR in response to combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats. It is possible that these finding will provide useful insight for the clinical use of electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus as a therapeutic tool in patients with resistant hypertension and/or heart failure.

Methods

All procedures used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Committee of Ethics in Animal Research of the Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (Protocol N. 143/2013).

Surgical procedures and experimental groups

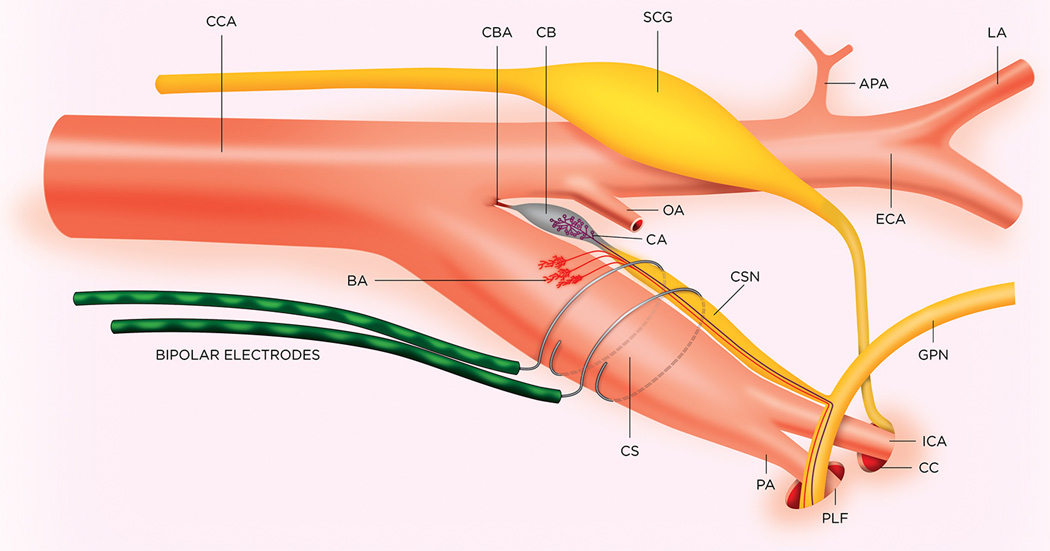

The surgical procedures were carried out under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. All rats were implanted with polyethylene catheters into the left femoral artery and vein for arterial pressure recording and drug administration, and underwent right side carotid chemoreceptor denervation as described elsewhere.8 Before the implantation of a bipolar stainless steel electrode around the left carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve (Figure 1) twenty-seven rats were assigned into 4 experimental groups:

Control group (CONT; n = 7): Left carotid bifurcation was maintained intact;

Chemoreceptor denervation group (CHEMO-X; n = 7): Left carotid body denervation was performed by cutting off the carotid body artery.8

Baroreceptor denervation group (BARO-X; n = 6): Left carotid baroreceptor denervation was performed by carefully cutting off the baroreceptor afferents from the carotid sinus.

Carotid bifurcation denervation group (TOTAL-X; n = 7): Left carotid chemoreceptor and baroreceptor denervation was performed according to the procedures described in items 2 and 3 above.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the position of the bipolar electrodes on left carotid sinus of the rat; APA, ascending pharyngeal artery; BA, baroreceptor afferents; CA, chemoreceptor afferents; CB, carotid body; CBA, carotid body artery; CCA, common carotid artery; CC, carotid canal; CS, carotid sinus; CSN, carotid sinus nerve; ECA, external carotid artery; GPN, glossopharyngeal nerve; ICA, internal carotid artery; LA, lingual artery; OA, occipital artery; PA, pterygopalatine artery; PLF, posterior lacerated foramen; SCG, superior cervical ganglion. Adapted, with permission, from Sapru HN and Krieger AJ. Carotid and aortic chemoreceptor function in the rat. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1977;42:344–348.

For detailed surgical procedures see the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org.

Experimental protocol

Twenty-four hours after surgical procedures, conscious freely moving rats had the pulsatile arterial pressure recorded during 20 min under baseline conditions, followed by successive 20 s long sessions of combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve (voltage: 5 V; pulse width: 1 ms; frequency: 15 Hz, 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz, applied in a random order). At least a 5 min interval was observed for each period of stimulation. Baseline values of MAP and HR were collected from a 20 s period which preceded the beginning of each frequency of electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus. The maximum responses in MAP and HR to electrical stimulations were recorded.

For expanded Methods section see the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org.

Results

Basal hemodynamics

Baseline values of systolic arterial pressure, diastolic arterial pressure, MAP, and HR from all groups are shown in Table 1. The hemodynamic parameters were not statistically different among all groups.

Table 1.

Baseline values of systolic (SAP, mmHg), diastolic (DAP, mmHg) and mean arterial pressure (MAP, mmHg) and heart rate (HR, bpm).

| Variables | CONT (n = 7) |

CHEMO-X (n = 7) |

BARO-X (n = 6) |

TOTAL-X (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAP | 117 ± 3 | 122 ± 5 | 128 ± 3 | 116 ± 4 |

| DAP | 89 ± 2 | 86 ± 3 | 90 ± 2 | 84 ± 2 |

| MAP | 103 ± 2 | 102 ± 3 | 107 ± 3 | 99 ± 2 |

| HR | 369 ± 10 | 352 ± 15 | 343 ± 9 | 347 ± 8 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. CONT, control; CHEMO-X, carotid body denervation; BARO-X, baroreceptor denervation; TOTAL-X, carotid body plus baroreceptor denervation.

Hemodynamic responses to combined electrical stimulation of the left carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve

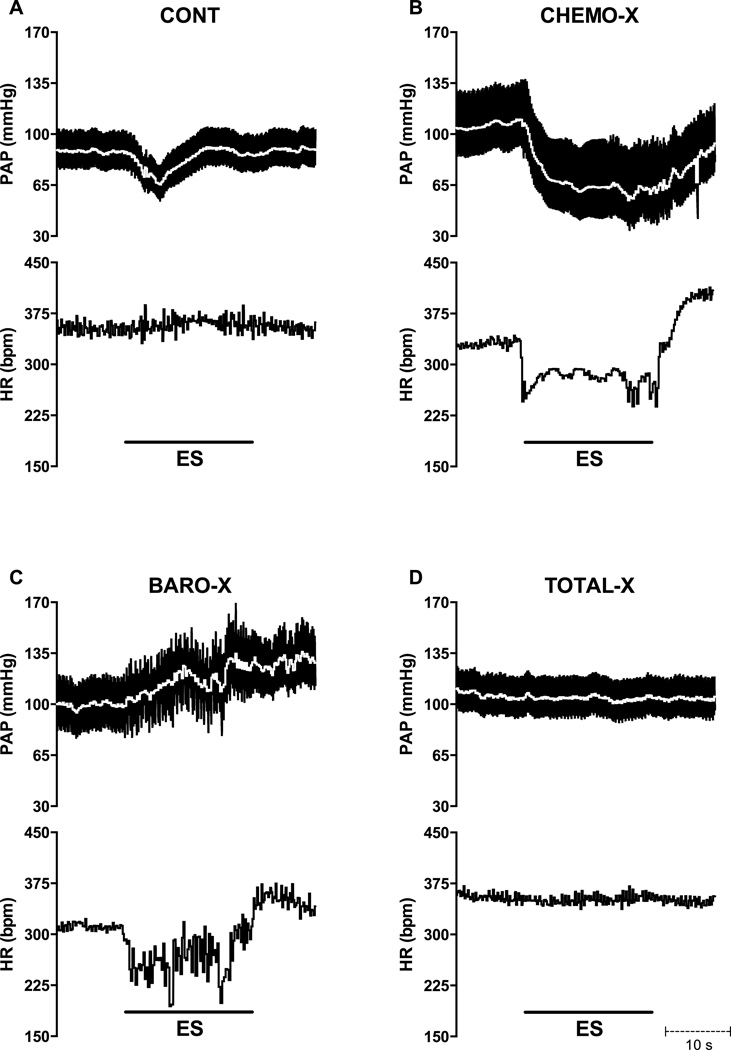

Typical traces of the responses of pulsatile arterial pressure, MAP (white line; top), and HR (bottom) to 20 s combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats are displayed in Figure 2. CONT and CHEMO-X rats exhibited hypotensive responses, whereas the BARO-X rat exhibited a hypertensive response. No change in arterial pressure was observed in the TOTAL-X rats. The HR recordings show that CHEMO-X and BARO-X rats displayed marked bradycardia, whereas the CONT and TOTAL-X rats presented no change in HR.

Figure 2.

Representative traces showing pulsatile arterial pressure (PAP), mean arterial pressure (MAP; white line; top), and heart rate (HR; bottom) responses to combined electrical stimulation (5 V; 1 ms; 90 Hz) of the carotid sinus and carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats during 20s; CONT, control; CHEMO-X, denervated carotid body; BARO-X, denervated carotid baroreceptor; TOTAL-X, denervated carotid body plus denervated carotid baroreceptor.

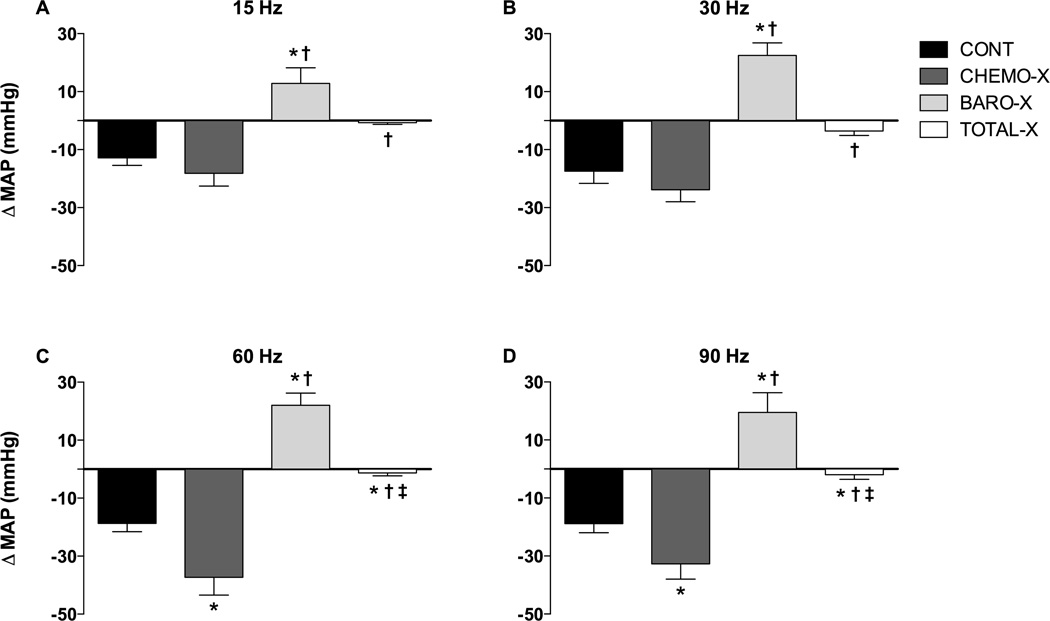

The responses of MAP to combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve with 15 Hz, 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz from all groups are shown in Figure 3. At all frequencies, CONT and CHEMO-X groups exhibited a hypotensive response. In contrast, the BARO-X group exhibited a hypertensive response under all frequencies of stimulation. The TOTAL-X group showed no changes in MAP with any frequency of stimulation. Figure S1 in the data supplement shows the MAP responses versus the frequencies of stimulation for all groups studied.

Figure 3.

Changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) in response to combined electrical stimulation (5 V; 1 ms; 15 Hz, 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz) of the carotid sinus and carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats during 20s; CONT, control; CHEMO-X, denervated carotid body; BARO-X, denervated carotid baroreceptor; TOTAL-X, denervated carotid body plus denervated carotid baroreceptor. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean; *P<0.05 compared to the CONT group; †P<0.05 compared to the CHEMO-X group; ‡P<0.05 compared to the BARO-X group.

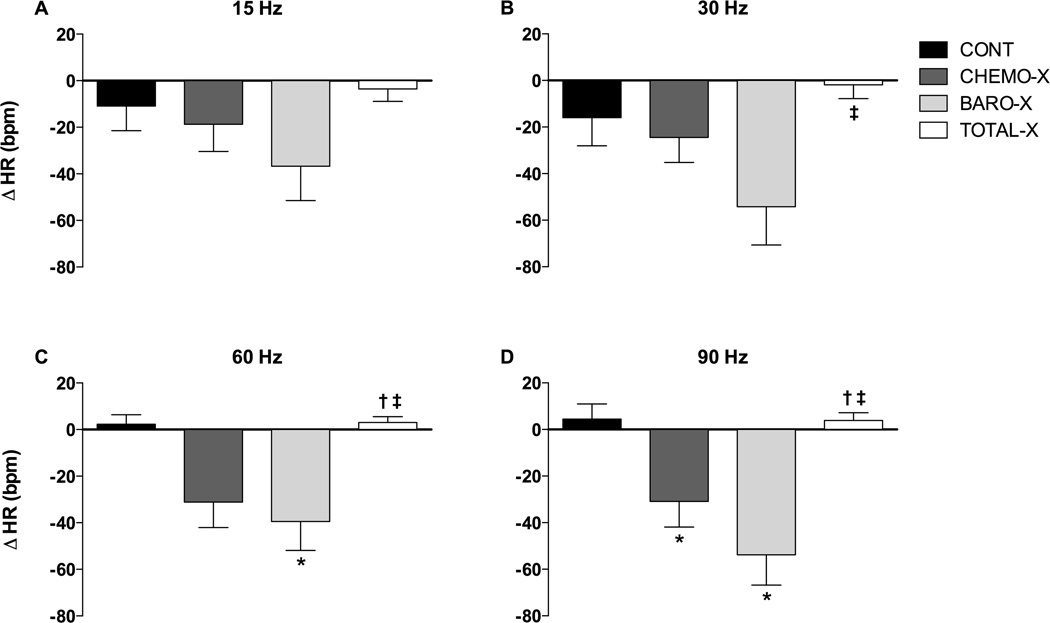

The HR responses to combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve with 15 Hz, 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz from all groups are shown in Figure 4. The CONT and TOTAL-X groups showed no changes in HR with any frequency of stimulation. The CHEMO-X and BARO-X groups displayed a trend toward bradycardic responses; however, the BARO-X group displayed significant bradycardia with stimulation at 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz, while the CHEMO-X group displayed bradycardia only upon stimulation with 60 Hz or 90 Hz. Figure S2 in the data supplement shows the individual hemodynamic responses to combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve with different frequencies (Hz) for all groups studied.

Figure 4.

Changes in heart rate (ΔHR) in response to combined electrical stimulation (5 V; 1 ms; 15 Hz, 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz) of the carotid sinus and carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats during 20s; CONT, control; CHEMO-X, denervated carotid body; BARO-X, denervated carotid baroreceptor; TOTAL-X, denervated carotid body plus denervated carotid baroreceptor. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean; *P<0.05 compared to the CONT group; †P<0.05 compared to the CHEMO-X group; ‡P<0.05 compared to the BARO-X group.

Discussion

The major new finding obtained from conscious rats was the clear-cut demonstration that chemoreceptors, as well as baroreceptors, were transiently activated during combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats. The results have shown that when the carotid bifurcation was intact (i.e. in the CONT group), combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve elicited a significant hypotensive response. This finding is in line with results obtained in dogs20,21 and drug-resistant hypertensive patients.1,2 Nevertheless, unlike the results seen in dogs22 and drug-resistant hypertensive patients,4 HR did not significantly decrease in intact conscious rats (the CONT group).

It is of interest to note that bilateral carotid body denervation (as in the CHEMO-X group) hampered the hemodynamic influences of the carotid chemoreceptors during combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats. This procedure led to an augmented hypotensive response, at frequencies of 60 Hz and 90 Hz, indicating that carotid chemoreceptor activation attenuated the hypotensive response elicited by the carotid baroreceptors in intact rats (i.e., the CONT group). Additionally, carotid baroreceptor denervation alone (i.e., the BARO-X group) led to a significant hypertensive response, combined with marked bradycardia, following electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus. This finding provides support for the hypothesis that carotid chemoreceptors were also activated during combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve. When the carotid sinus was electrically stimulated in the absence of carotid chemoreceptors and carotid baroreceptors (i.e., the TOTAL-X group), no changes in hemodynamic (MAP and HR) responses were observed. This finding provides additional support for the role played by the afferents from chemo- and baroreceptors when activated during combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve.

Regarding the reflex bradycardia, the CONT group showed no bradycardic response to combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve, whereas the chemoreceptor-denervated rats (the CHEMO-X group) showed consistent bradycardia. It is well known that baroreflex activation leads to vagally-mediated bradycardia.15 In addition, as previously indicated, peripheral chemoreflex activation also leads to bradycardia involving the parasympathetic drive.8,19 Nevertheless, the lack of conspicuous bradycardia following combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in rats from the CONT group is consistent with data from a previous report by Murata and colleagues.23 These authors demonstrated that carotid chemoreceptor activation through intracarotid injection of sodium cyanide inhibited the baroreflex vagal bradycardia elicited by electrical stimulation of the aortic depressor nerve in anesthetized rats. They concluded that a mechanism dependent on afferent inputs from the carotid chemoreceptors blunted the baroreceptor function.23

It is interesting that the absence of carotid baroreceptors (i.e., in the BARO-X group) appears to enable full electrical activation of the carotid chemoreceptors, because under these conditions, in addition to the already mentioned hypertensive responses, a significant bradycardia was observed at frequencies of 30 Hz, 60 Hz, and 90 Hz. The interplay of baro- and chemoreceptor control of autonomic function has been investigated under both experimental24–26 and clinical9,27,28 research conditions. Somers and colleagues9 provided direct evidence in humans of the unique ability of the chemoreflex to concurrently activate the parasympathetic drive to the heart and the sympathetic discharge to resistance vessels. Therefore, the remarkable bradycardia elicited by the activation of the chemoreflex in the absence of the baroreflex in conscious rats corroborates the hypothesis of a convergence of baroreceptor and peripheral chemoreceptor afferents on the medulla.23,27

Of note, the current study did not investigate the respiratory function during the combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats. Nevertheless, Alnima and colleagues16 demonstrated that a short-term (2 to 4 min) protocol for carotid BAT in patients with resistant hypertension caused no change in end-tidal carbon dioxide, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, breath duration, and breathing frequency, combined with highly significant decrease in mean arterial pressure during electric activation. These authors concluded that carotid BAT using the Rheos system involved no appreciable attendant activation of carotid body chemoreceptors during the device therapy.16 Certainly, this is not the case concerning the approach employed in the current study in conscious rats, which deserves a thorough investigation of the respiratory changes due to the direct activation of the carotid chemoreflex.

In conclusion, combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats produced a significant hypotensive response, which was potentiated by carotid body denervation. These findings demonstrated that concomitant carotid chemoreceptor activation blunts carotid baroreflex–mediated hypotension. Moreover, combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in the absence of the carotid baroreceptors, but with intact carotid chemoreceptors, caused hypertension and bradycardia; this observation provides support for the hypothesis that carotid chemoreceptors are concomitantly activated by combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve. Finally, the absence of chemo- and baroreceptor afferents hampered any reflex hemodynamic response (MAP and HR) elicited by unilateral combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats.

Perspectives

Combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve in conscious rats is a useful experimental model that, from the translational point of view, may bring important insights into the mechanisms underlying baroreflex activation therapy (BAT). Using this experimental model, the present study shows that combined electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus and the carotid sinus nerve concomitantly activates both carotid baroreceptors and chemoreceptors, indicating that attendant carotid chemoreceptor activation blunted the hypotensive response in conscious rats. Nevertheless, it is of note that recent study of Alnima and colleagues16 indicates no relevant carotid body coactivation with Rheos system in patients with resistant hypertension, probably because their pulse generator is implanted at the surface of each carotid sinus wall without reaching the nearby located carotid body chemoreceptors.16

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

Baroreflex Activation Therapy (BAT) applied to resistant hypertension and/or heart failure has been developed recently aiming to inhibit sympathetic overactivity and increase parasympathetic tone in patients with resistant hypertension and/or heart failure. Even though this clinical approach takes into account the carotid baroreflex activation, it is possible that some other mechanism, for instance, the peripheral chemoreflex, may be involved in this device-based therapeutical approach. Therefore, it was examined, in conscious rats, the role played by the activation of the peripheral chemoreceptors concomitant with the electrical activation of the carotid baroreflex.

What Is Relevant?

Despite that BAT has shown promises results for resistant hypertension and/or heart failure therapy, the mechanisms involved in this clinical approach still deserve thorough investigation. Because clinically it is not easy to assess all mechanisms involved in BAT, an experimental model with selective denervation of carotid chemo- and/or baroreceptors in rats may bring new insights for better understanding these mechanisms.

Summary

This study demonstrates that carotid chemoreceptor activation attenuates the hypotensive response caused by electrical stimulation of the carotid baroreflex in conscious rats. Accordingly, this finding may provide useful insight for clinical studies using BAT in resistant hypertension and/or heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenadoria de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Bisognano JD, Bakris G, Nadim MK, Sanchez L, Kroon AA, Schafer J, de Leeuw PW, Sica DA. Baroreflex activation therapy lowers blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled rheos pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Leeuw PW, Kroon AA, Scheffers I. Baroreflex hypertension therapy with a chronically implanted system: preliminary efficacy and safety results from the Rheos DEBuT-HT study in patients with resistant hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24:S300–S301. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heusser K, Tank J, Engeli S, Diedrich A, Menne J, Eckert S, Peters T, Sweep FC, Haller H, Pichlmaier AM, Luft FC, Jordan J. Carotid baroreceptor stimulation, sympathetic activity, baroreflex function, and blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2010;55:619–626. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alnima T, de Leeuw PW, Kroon AA. Baroreflex activation therapy for the treatment of drug-resistant hypertension: new developments. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:587194. doi: 10.1155/2012/587194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiBona GF. Sympathetic nervous system and hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:556–560. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doumas M, Faselis C, Kokkinos P, Anyfanti P, Tsioufis C, Papademetriou V. Carotid baroreceptor stimulation: a promising approach for the management of resistant hypertension and heart failure. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2014;12:30–37. doi: 10.2174/15701611113119990138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zucker IH, Hackley JF, Cornish KG, Hiser BA, Anderson NR, Kieval R, Irwin ED, Serdar DJ, Peuler JD, Rossing MA. Chronic baroreceptor activation enhances survival in dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Hypertension. 2007;50:904–910. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franchini KG, Krieger EM. Cardiovascular responses of conscious rats to carotid body chemoreceptor stimulation by intravenous KCN. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1993;42:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90342-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somers VK, Dyken ME, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Parasympathetic hyperresponsiveness and bradyarrhythmias during apnoea in hypertension. Clin Auton Res. 1992;2:171–176. doi: 10.1007/BF01818958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBryde FD, Abdala AP, Hendy EB, Pijacka W, Marvar P, Moraes DJ, Sobotka PA, Paton JF. The carotid body as a putative therapeutic target for the treatment of neurogenic hypertension. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2395. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paton JF, Sobotka PA, Fudim M, Engelman ZJ, Engleman ZJ, Hart EC, McBryde FD, Abdala AP, Marina N, Gourine AV, Lobo M, Patel N, Burchell A, Ratcliffe L, Nightingale A. The carotid body as a therapeutic target for the treatment of sympathetically mediated diseases. Hypertension. 2013;61:5–13. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus NJ, Del Rio R, Schultz EP, Xia XH, Schultz HD. Carotid body denervation improves autonomic and cardiac function and attenuates disordered breathing in congestive heart failure. J Physiol (Lond) 2014;592:391–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.266221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Leeuw PW, Alnima T, Lovett E, Sica D, Bisognano J, Haller H, Kroon AA. Bilateral or unilateral stimulation for baroreflex activation therapy. Hypertension. 2015;65:187–192. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan J, Heusser K, Brinkmann J, Tank J. Electrical carotid sinus stimulation in treatment resistant arterial hypertension. Auton Neurosci. 2012;172:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieger EM, Salgado HC, Michelini LC. Resetting of the baroreceptors. Int Rev Physiol. 1982;26:119–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alnima T, Goedhart EJ, Seelen R, van der Grinten CP, de Leeuw PW, Kroon AA. Baroreflex activation therapy lowers arterial pressure without apparent stimulation of the carotid bodies. Hypertension. 2015;65:1217–1222. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Paula PM, Castania JA, Bonagamba LG, Salgado HC, Machado BH. Hemodynamic responses to electrical stimulation of the aortic depressor nerve in awake rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;277:R31–R38. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.1.R31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand MT, Castania JA, Fazan R, Jr, Salgado MC, Salgado HC. Hemodynamic responses to aortic depressor nerve stimulation in conscious L-NAME-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R418–R427. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00463.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franchini KG, Krieger EM. Carotid chemoreceptors influence arterial pressure in intact and aortic-denervated rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1992;262:R677–R683. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lohmeier TE, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Serdar DJ, Kieval RS. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex produces sustained hypotension. Hypertension. 2004;43:306–311. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111837.73693.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabbah HN, Ilsar I, Zaretsky A, Rastogi S, Wang M, Gupta RC. Vagus nerve stimulation in experimental heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hildebrandt DA, Irwin ED, Cates AW, Lohmeier TE. Regulation of renin secretion and arterial pressure during prolonged baroreflex activation: influence of salt intake. Hypertension. 2014;64:604–609. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murata T, Otsu K, Kobayashi M, Nosaka S. Inhibition of baroreflex vagal bradycardia by selective stimulation of arterial chemoreceptors in rats. Exp Physiol. 1999;84:897–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heistad D, Abboud FM, Mark AL, Schmid PG. Effect of baroreceptor activity on ventilatory response to chemoreceptor stimulation. J Appl Physiol. 1975;39:411–416. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mancia G. Influence of carotid baroreceptors on vascular responses to carotid chemoreceptor stimulation in the dog. Circ Res. 1975;36:270–276. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oikawa S, Hirakawa H, Kusakabe T, Nakashima Y, Hayashida Y. Autonomic cardiovascular responses to hypercapnia in conscious rats: the roles of the chemo- and baroreceptors. Auton Neurosci. 2005;117:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Somers VK, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1953–1957. doi: 10.1172/JCI115221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Timmers HJ, Wieling W, Karemaker JM, Lenders JW. Denervation of carotid baro- and chemoreceptors in humans. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;553:3–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.