Abstract

Breaking up sitting time with light- or moderate-intensity physical activity may help to alleviate some negative health effects of sedentary behavior, but few studies have examined ways to effectively intervene. This feasibility study examined the acceptability of a new technology (NEAT!) developed to interrupt prolonged bouts (≥20 min) of sedentary time among adults with type 2 diabetes. Eight of nine participants completed a 1-month intervention and agreed that NEAT! made them more conscious of sitting time. Most participants (87.5 %) expressed a desire to use NEAT! in the future. Sedentary time decreased by 8.1 ± 4.5 %, and light physical activity increased by 7.9 ± 5.5 % over the 1-month period. The results suggest that NEAT! is an acceptable technology to intervene on sedentary time among adults with type 2 diabetes. Future studies are needed to examine the use of the technology among larger samples and determine its effects on glucose and insulin levels.

Keywords: m-Health, Physical activity, Sedentary, Type 2 diabetes, Technology

INTRODUCTION

Independent of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA), sedentary behavior, defined as activities between 1.0 and 1.5 metabolic equivalents, is associated with increased risk of disability [1] and premature mortality [2]. Prolonged sedentary time is also linked with numerous health conditions, including cardiovascular disease [3, 4], metabolic syndrome [5, 6], obesity [7], and breast cancer [8]. In addition, a large amount of sitting is associated with a 112 % increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes and has detrimental effects on insulin resistance and glycemia [3, 9]. Increased levels of 2 h plasma glucose are seen not only in those with increased total sedentary time but also in those who have fewer interruptions in sedentary time [10–12]. Recent experimental findings suggest that breaking up prolonged bouts (≥20 min) of sedentary behavior with either light- or moderate-intensity physical activity for 2 min reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses [13]. With the increased prevalence and rising economic costs of diagnosed diabetes in the USA, targeting sedentary time among this population may be an appropriate strategy to intervene and reduce the substantial economic burden and health consequences of diabetes [14].

Physiologically, sedentary behavior has distinct biological effects that are different from those of merely not engaging in sufficient MVPA [15–17]. Duvivier et al. [18] recently reported that engaging in 1 h of vigorous exercise cannot compensate for sedentary behavior’s negative effects on insulin sensitivity and plasma lipids. In addition to higher-intensity activity, light-intensity physical activity, which has been shown to be inversely related to sedentary time, may have beneficial effects on health [11, 19]. Specifically, substituting sitting time with light-intensity activity was more effective at improving insulin levels than 1 h of MVPA [18]. Thus, replacing sedentary time with light-intensity activity or nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) may help to reduce the health consequences of sedentary behavior. NEAT is defined as the energy expenditure of all physical activities with the exception of purposeful exercise [20]. Examples of NEAT include standing or light ambulation. Given the strong association between sedentary time and glucose levels, substituting sedentary behavior with NEAT may provide an opportunity to improve metabolic risk variables among the estimated 20.4 million American adults who have diabetes [21].

Many studies have sought to reduce total or leisure sedentary time [22–25]; however, few have examined breaking up sedentary bouts [26]. Evans et al. [26] examined the use of computer software that encourages individuals to stand up every 30 min, but differences in total sedentary time were not observed between the intervention and control groups. These null findings could be attributed to the treatment which only intervened on sedentary time during work hours. Moreover, the software used in the study by Evans et al. [26] prompted individuals to stand regardless of their context (e.g., a person might be prompted to stand even if he was already standing at a desk). A mobile device, such as a smartphone, offers a potentially feasible and adaptable channel to use to intervene on sedentary behavior. Smartphone use has continued to rise in the USA [27]: as of January 2014, 58 % of American adults owned a smartphone, with usage rates even higher among African American and Hispanic populations [27]. Hence, utilizing smartphone technology may also provide an opportunity to intervene upon ethnic minority populations who are disproportionately affected by diabetes [21].

We developed the NEAT! smartphone application to encourage adults with diabetes to interrupt prolonged bouts of objectively measured sedentary behavior. If interventions to break up extended bouts of sitting time are effective, they might potentially prevent diabetes or reduce glucose levels among those diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. NEAT! works in conjunction with a wireless accelerometer (Shimmer, Dublin, Ireland) that measures physical activity. When a sedentary bout, defined as ≥20 min based on the experimental findings by Dunstan et al. [13], is detected from the accelerometer, the smartphone application triggers a reminder prompt to the user encouraging him/her to engage in light-intensity physical activity for at least 2 min. The purpose of this feasibility study was to examine the acceptability of using NEAT! during a 1-month period among adults with type 2 diabetes.

METHODS

Participants

This pilot and feasibility study enrolled nine sedentary adults between 21 and 70 years old with physician-diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Participants also needed to own an Android smartphone, be willing to wear an intervention accelerometer and use the NEAT! application on their smartphone, and have a sedentary occupation or spend ≥75 % of the day sitting. Participants were excluded if they were unable to ambulate without assistance or did not wear the assessment accelerometer >7 days at baseline. Prior to participating in any study procedure, all potential participants voluntarily provided informed consent. All study procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment and screening

Participants were recruited via flyers posted in the Chicago land community and online postings (e.g., Craigslist). Flyers and postings listed a brief description of the study and eligibility criteria and directed interested participants to contact the study coordinator by phone or e-mail. Once participants expressed interest in the study via contacting the study coordinator, study staff contacted participants to provide a detailed explanation of the study, confirm their intent to participate, and obtain verbal assent for the phone screen. Staff asked screening questions related to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Interested and eligible participants attended a 1-h baseline session, in which they were given complete details about the study and learned about the technology used in the study. Informed consent was obtained from all interested participants. After signing informed consent, participants completed baseline measures and were provided with an assessment accelerometer (Actigraph 7164, Actigraph Inc., Pensacola, FL) to wear during waking hours for 10–12 days. Participants did not receive any feedback on their sedentary time and were encouraged to engage in their typical behavior during this period.

NEAT! intervention

Eligible participants returned for a 1-h orientation session to return the assessment accelerometer, downloaded NEAT! onto their personal smartphone and were provided with an intervention accelerometer (Shimmer). Study staff conducted a brief tutorial on how to use the technology. Participants were instructed to use NEAT! and wear the intervention accelerometer around their waist during waking hours for 1 month. When 20 min of consecutive sedentary time was detected from the intervention accelerometer [13], the NEAT! application initiated a noise or vibration prompt based on the participant’s preference, encouraging him/her to stand up (Fig. 1). To gain a better understanding of whether and why participants would adhere or not to the prompts, participants were asked to indicate how they would react to the prompt. The four response options were: (1) Stand—indicating that the participant would engage in any type of light-intensity physical activity, such as standing or light ambulation for ≥2 min, (2) Extend—indicating that the participant would extend the duration of the sedentary bout by an additional 1 to 19 min (e.g., to finish a meal); (3) Cannot stand—indicating that the participant is unable to engage in light-intensity physical activity because of his/her current situation (e.g., in a sedentary work meeting), or (4) Ignore—indicating that the participant could stand up, however is choosing to ignore or dismiss the prompt and remain sedentary. Whenever a sit-to-stand transition was detected objectively or the participant responded to the prompt on the phone, the sedentary counter was restarted. However, if the participant responded that he/she intended to “stand” but did not actually stand, additional reminders were sent every 2 min until either the participant stood up or chose a different response to the prompt.

Fig. 1.

NEAT! smartphone application and accelerometer

MEASURES

NEAT! usage and evaluation

NEAT! application and intervention accelerometer usage were examined over the 1-month period. Participants also completed a 16-item questionnaire and a brief 14-question interview with a staff member at the 1-month assessment to examine the acceptability of the NEAT! technology. The questionnaire and interviews addressed current perception, liking, barriers, and future use of the application and intervention accelerometer. The frequency of responses obtained from the NEAT! evaluation questionnaire were examined.

Anthropometric data

Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) without shoes were obtained from participants at baseline. Height was measured using a wall-mounted stadiometer. Body weight was measured via a calibrated balance beam scale with participants wearing lightweight clothing. BMI was calculated as kilograms per square meter.

Sedentary behavior and physical activity

Participants wore an assessment accelerometer (Actigraph 7164, Actigraph Inc., Pensacola, FL) for a 10–12-day period at baseline (prior to using the NEAT! application and accelerometer) and again during the last 10 days of the 1-month intervention period. During the 1-month period, participants wore both the assessment and intervention accelerometers at the same time. Since the intervention accelerometer (Shimmer) has not been validated, it was only used for intervention purposes and an additional accelerometer (Actigraph) was used for assessment purposes. The assessment accelerometer was initialized to measure vertical movements ten times each second and translated on a minute-by-minute basis. Counts were categorized into sedentary- (<100 counts/min (cpm)), light- (100–1951 cpm), or moderate-vigorous-intensity physical activity (≥1952 cpm) [28, 29]. The percentage of wear time of each day spent in sedentary behavior, light-intensity activity, or moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity was calculated to account for differences in accelerometer wear time. Breaks in sedentary time were defined as a transition from sedentary (<100 cpm) to an active state (≥100 cpm) [12] and were summed over valid days (≥10 h of wear time). The average intensity (cpm) and duration of sedentary breaks were also calculated.

Statistical analysis

Baseline descriptive statistics were computed. Averages for the following NEAT! usage data were examined: (1) technology usage (days/month and hours/day) and (2) NEAT! prompt response (daily times used). The frequency of response was calculated for the NEAT! evaluation survey and an inductive thematic analysis was used to determine the pattern of responses to the interview on the evaluation of the NEAT! technology. Percentage analysis was also used to compare and contrast emerging themes. Paired samples t tests were used to examine changes between baseline and 1 month. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics v22.

RESULTS

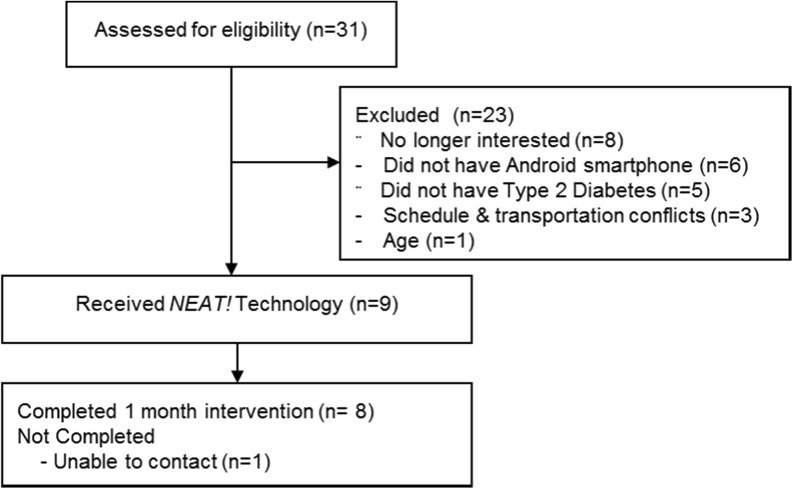

A total of nine participants were recruited to participate in this study (Fig. 2). Participants were 53.1 ± 10.7 years (mean ± SD) and had a BMI of 37.4 ± 9.9 kg/m2 (89 % overweight or obese). Seven of the nine participants were female (77 %). All participants were non-Hispanic (77 % Black and 23 % White). Participants were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes between 1 and 13 years ago (median = 4 years). Eight of the nine participants completed the 1-month intervention.

Fig. 2.

Participant flowchart of recruitment, enrollment, and retention

NEAT! usage

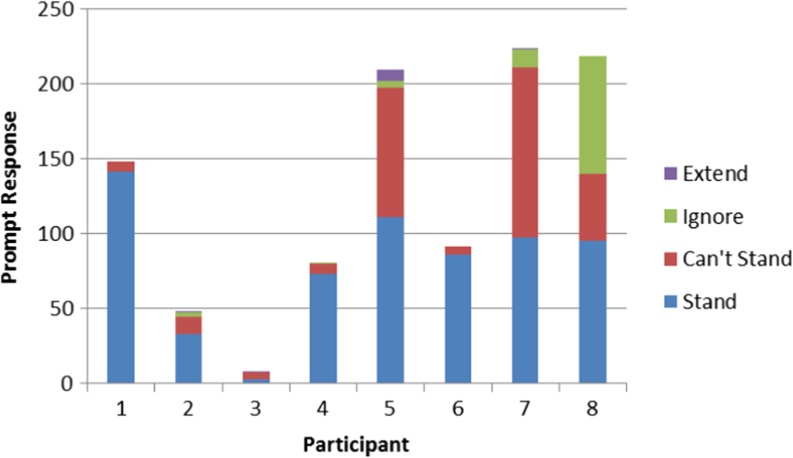

Over the 1-month period, participants used the NEAT! technology on 21.9 ± 8.0 days for 7.6 ± 2.5 h/day. Participants were prompted to stand 128.4 ± 83.4 times/month or approximately 5.8 ± 3.5 times/day. The breakdown of the type of each participant’s response to each prompt to stand up is displayed in Fig. 3. On average, participants selected “stand” 62.6 % of the time.

Fig. 3.

Prompt response by individual participant

NEAT! acceptability

The results of the technology evaluation are presented in Table 1. All participants who completed the intervention (n = 8) agreed or strongly agreed that the NEAT! technology made them more aware of their sitting time and motivated them to stand up. Only one participant indicated that the technology was not easy to use and that it interfered with his/her social life. Seven of the eight participants (87.5 %) of participants indicated that they would use the NEAT! technology in the future. Of the participants that would use the technology in the future, participants indicated that they would wear it every day (n = 2), at least 3 days/week (n = 3), or only when sitting for extended periods (n = 2).

Table 1.

NEAT! technology evaluation

| Category and item “statements” | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | Not applicable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The NEAT! technology made it easier to break up my sitting time compared with if I did not use the technology. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 4 (50 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| The NEAT! technology made me more aware of how much time I spend sitting compared with if I did not use the technology. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 7 (87.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| The NEAT! technology motivated me to stand up more frequently compared with if I did not use the technology. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 5 (62.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| The NEAT! technology motivated me to decrease the amount of time I spent sitting compared with if I did not use the technology. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 4 (50 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| The NEAT! technology was easy to use. | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 5 (62.5 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Using the NEAT! technology did not interfere with my job. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 2 (25 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 2 (25 %) | 1 (12.5 %) |

| Using the NEAT! technology did not interfere with my social life. | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 0 (0 %) | 6 (75 %) | 1 (15.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Using the NEAT! technology did not make me feel uncomfortable around others. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 5 (62.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| The NEAT! intervention accelerometer was comfortable to wear. | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 2 (25 %) | 2 (25 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Wearing the NEAT! intervention accelerometer did not interfere with my job. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 5 (62.5 %) | 2 (25 %) | 1 (12.5 %) |

| Wearing the NEAT! intervention accelerometer did not interfere with my social life. | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 0 (0 %) | 4 (50 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Wearing the NEAT! intervention accelerometer did not make me feel uncomfortable around others. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 4 (50 %) | 4 (50 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| I would use the NEAT! Technology in the future. | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 4 (50 %) | 0 (0 %) |

Interview responses indicated that participant’s attitudes to the NEAT! technology were largely positive. In response to the question “Did you think the NEAT! technology helped you take more breaks from sitting,” 87.5 % of participants indicated that they thought the technology helped them take more breaks from sitting. One participant commented, “It would remind me that I had been sitting for a period of time, without having to think about it.” Another participant indicated that, “I found I was more productive because it interrupted my sitting around doing nothing.” In response to “What did you like about the NEAT! application and shimmer,” the most common response (50 %) was that participants thought the technology was easy to use. However, some barriers were also mentioned including the short intervention accelerometer battery life and that the technology only worked when the intervention accelerometer and phone were wirelessly connected. One participant commented, “Wished I would have remembered to bring my phone every time I stood up and walked away.” In response to “What did you think of the duration (20 minutes) of sitting time before being prompted to stand up?” 75 % of participants thought that the 20-min sitting duration was acceptable, although one participant suggested allowing for a 10-min break following a 1-h sedentary period. All participants also thought the requirement to take at least a 2-min break period from sitting was reasonable. One participant commented, “I didn’t think too much about it and actually would stand up and move longer.” Thirty-seven percent of participants indicated that they liked having the “can’t stand” function to explain that it was not by personal choice that they remained sedentary at times of prompts. For example, two participants specified that they would use the “can’t stand” option when in a meeting or working on a project.

Changes in sedentary behavior and physical activity

Sedentary time and physical activity were measured using an assessment accelerometer at baseline as well as at 1 month when also using the NEAT! technology. Individual participant data presented in Table 2 show that seven of the eight participants reduced their time in sedentary behavior and increased light intensity while using NEAT!. The change in the percent of the day spent in sedentary behavior ranged from decreasing by −12.8 % to increasing by 11.2 % while using the NEAT! technology (Table 3). One individual outlier (participant No. 8) showed opposite changes as compared with the other participants and was 2.1 standard deviations above the mean for change in percent of day spent in sedentary behavior. Among the seven participants, daily percent sedentary time decreased by 8.1 ± 4.5 % (p = 0.003) between baseline and 1 month, and daily percent of time spent in light-intensity physical activity increased by 7.9 ± 5.5 % (p = 0.009). Including participant No. 8 in the analyses reduced the decrease in sedentary time to the level of a trend (p = 0.08) and maintained a significant increase in light activity (p = 0.047). There were no significant changes in the percent of day spent in moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity. Assessment accelerometer wear time decreased significantly between baseline and 1 month (p = 0.008). Breaks in sedentary time also decreased by 15.8 ± 8.8 breaks (p = 0.003), whereas break duration significantly increased by 1.0 ± 0.5 min (p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Individual changes in sedentary behavior and light-intensity activity

| Participant | Sedentary time (%/day) | Light-intensity physical activity (%/day) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 month | Change | Baseline | 1 month | Change | |

| 1 | 78.9 ± 5.9 | 71.9 ± 8.6 | −7.0 | 20.8 ± 5.8 | 27.5 ± 8.6 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 70.9 ± 6.4 | 61.2 ± 9.1 | −9.7 | 28.4 ± 6.2 | 37.7 ± 8.5 | 9.3 |

| 3 | 66.5 ± 6.0 | 56.4 ± 11.6 | −10.1 | 30.8 ± 5.5 | 41.4 ± 11.8 | 10.6 |

| 4 | 66.1 ± 7.9 | 53.7 ± 3.6 | −12.4 | 30.0 ± 6.7 | 45.5 ± 3.7 | 15.5 |

| 5 | 73.7 ± 6.4 | 72.6 ± 7.4 | −1..1 | 23.3 ± 6.7 | 23.7 ± 7.8 | 0.4 |

| 6 | 58.4 ± 6.2 | 45.6 ± 7.0 | −12.8 | 40.4 ± 6.0 | 51.7 ± 6.4 | 11.3 |

| 7 | 69.2 ± 10.5 | 65.8 ± 4.3 | −3.4 | 30.1 ± 10.7 | 31.2 ± 4.2 | 1.1 |

| 8 | 56.5 ± 8.3 | 67.7 ± 6.7 | 11.2 | 33.6 ± 6.7 | 27.3 ± 6.8 | -6.3 |

Table 3.

Changes in sedentary behavior and physical activity

| Variable (n = 7) | Baseline | 1 month | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary time (%/day) | 69.1 ± 6.5 | 61.0 ± 9.9 | 0.003* |

| Light-intensity physical activity (%/day) | 29.1 ± 6.3 | 36.9 ± 10.1 | 0.009* |

| MVPA (%/day) | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 0.752 |

| Accelerometer wear time (min/day) | 884.7 ± 61.1 | 746.3 ± 76.3 | 0.008* |

| Breaks/day in sedentary time | 83.4 ± 13.0 | 67.6 ± 15.1 | 0.003* |

| Break duration (min) | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 0.002* |

| Break intensity (cpm) | 474.0 ± 95.6 | 541.3 ± 83.3 | 0.229 |

MVPA moderate to vigorous physical activity

*p ≤ 0.01

DISCUSSION

The current study suggests that the NEAT! technology is a feasible and acceptable tool to intervene on sedentary time among adults with type 2 diabetes, who may be unduly adversely affected by excessive sitting. Participants used the technology for an average of 21 days over a 1-month period and indicated that using the technology made them more aware of how much time they spent sitting. Furthermore, the majority of individuals agreed that they would use the technology in the future if it were available, further suggesting NEAT!’s acceptability. As smartphone usage in the USA continues to rise [27], this ubiquitous technology may provide an opportunity to intervene to improve the health of a large proportion of the population.

In order to evaluate if participants would adhere to the “stand” prompt, as well as why they might not adhere, participants were asked to respond to all of the prompts. Participants in the current study responded that they would adhere, or “stand,” to 62 % of the prompts. This suggests that participants are willing to break up more than half of their prolonged sedentary bouts if reminders are given. Moreover, the majority of participants thought that it was acceptable to break up sedentary bouts lasting 20 min. This provides a helpful preliminary benchmark for future studies aiming to encourage breaks from sitting.

In addition to examining the feasibility and acceptability of the NEAT! technology, this study evaluated the preliminary efficacy of the intervention for changing sedentary time and physical activity. When examining individual changes, 87.5 % of participants reduced sedentary time and increased light-intensity physical activity. Several other trials have demonstrated promise in reducing sedentary time among office workers using various interventions that include computer software [26], computer software and text messages [30], sit-stand workstations [23, 31], portable pedal bike [24], or an in-person session [32]. Furthermore, the magnitude of changes in sedentary time and light activity in the current trial (sedentary change, −8.1 %; light activity change, 7.9 %) were slightly larger than those seen in a recent trial by Bond et al. [33] that used similar technology to interrupt sedentary time (sedentary change, -3.3 to −5.9 %; light activity change, 2.7 to 4.7 %).

Breaks in sedentary time also were examined. Contrary to our hypothesis, breaks decreased when using the technology as compared with baseline. The number of breaks in sedentary time observed at baseline (83 breaks) are similar to the average number of breaks reported by Cooper et al. [34] (84 breaks) among individuals newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The break duration and intensity found at baseline and 1 month were also comparable with those reported in a cross-sectional study conducted by Healy et al. [12]. The observed decrease in assessment accelerometer wear time may have contributed to the decreased number of breaks observed at 1 month. In addition, the break duration was longer at 1 month, indicating that when sedentary time was interrupted, longer breaks before sitting back down again were taken.

Because the sample size was small and the study was not powered to detect differences, no definitive conclusions can be drawn base on the results. An additional limitation is that sedentary time or inactivity was measured using an Actigraph accelerometer. Even though the Actigraph can provide estimates of sedentary time, it may be preferable for future studies to use a monitor that can detect body position and posture, so as to more accurately discriminate sitting time from standing [35].

This small feasibility study encountered several challenges. First, the NEAT! intervention accelerometer had a short battery life. Since the technology was generally only used until the battery died, the average wear time of the intervention accelerometer was only 7.6 h/day. Others have also reported challenges with battery life when continuously monitoring sedentary time [30]. A second challenge encountered was that the NEAT! intervention accelerometer and smartphone application only worked when the two were within 15 ft of each other and Bluetooth connected. Several participants indicated that when the prompt went off, they would stand up and walk away from their desk or couch. If they forgot to bring their phone, the intervention accelerometer would disconnect from the application and data would no longer be collected. This resulted in missing data following prompts and the inability to objectively assess adherence to the prompts. Future studies should adapt this technology to utilize an accelerometer with a longer battery life, allowing for the ability to continuously collect data even if the accelerometer is not wirelessly connected to the smartphone application.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the expected rise in the prevalence of diabetes in the USA [36], as well as the strong detrimental association between sedentary time and insulin or glucose levels [19, 32, 37, 38], innovative approaches are needed to break up prolonged sedentary behavior among the large proportion of the population affected by diabetes. The results of this study suggest that the NEAT! technology is an acceptable tool for use by adults with type 2 diabetes. Additional refinement of the technology is needed further to optimize improvements in sedentary time, physical activity, and breaks in sedentary behavior. Examination of longer-term effects of using the technology on glucose and insulin levels is also warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 KD092949), the Dean’s office of the Biological Sciences Division of the University of Chicago, and NIDDK R01 DK097364. The authors thank Jennifer Warnick for her assistance with the qualitative analyses.

Conflict of interest

No competing financial interests exist.

Adherence to ethical principles

All procedures performed, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the approving institutional review boards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Practitioners may consider recommending breaking up prolonged sedentary bouts, particularly for those who spend the majority of the day sitting.

Policy: Policymakers should consider developing appropriate recommendations for sedentary behavior.

Research: More research is needed to further examine the role of technology in interrupting prolonged bouts of sedentary behavior and determine whether this can significantly improve biomarkers.

Contributor Information

Christine A. Pellegrini, Phone: 312-503-1395, Email: c-pellegrini@northwestern.edu

Sara A. Hoffman, Phone: 312-503-3516, Email: sara.hoffman@northwestern.edu

Elyse R. Daly, Phone: 312-503-0816, Email: elyse.daly@northwestern.edu

Manuel Murillo, Phone: 312-503-0816, Email: manuelmurillo26@gmail.com.

Gleb Iakovlev, Phone: 312-503-5105, Email: g-iakovlev@northwestern.edu.

Bonnie Spring, Phone: 312-908-2293, Email: bspring@northwestern.edu

References

- 1.Dunlop D, Song J, Arnston E, et al. Sedentary Time in U.S. Older Adults associated with disability in activities of daily living independent of physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Patel AV, Bernstein L, Deka A, et al. Leisure time spent sitting in relation to total mortality in a prospective cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):419–429. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grontved A, Hu FB. Television viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2448–2455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chomistek AK, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Relationship of sedentary behavior and physical activity to incident cardiovascular disease: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2346–2354. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bankoski A, Harris TB, McClain JJ, et al. Sedentary activity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):497–503. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisson SB, Camhi SM, Church TS, et al. Leisure time sedentary behavior, occupational/domestic physical activity, and metabolic syndrome in U.S. men and women. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7(6):529–536. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, et al. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1785–1791. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch B, Dunstan D, Healy G, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time of breast cancer survivors, and associations with adiposity: findings from NHANES (2003–2006) Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(2):283–288. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55(11):2895–2905. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, et al. Objectively measured light-intensity physical activity is independently associated with 2-h plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1384–1389. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healy GN, Wijndaele K, Dunstan DW, et al. Objectively measured sedentary time, physical activity, and metabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):369–371. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, et al. Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):661–666. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):976–983. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bey L, Hamilton MT. Suppression of skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity during physical inactivity: a molecular reason to maintain daily low-intensity activity. J Physiol. 2003;551(Pt 2):673–682. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Exercise physiology versus inactivity physiology: an essential concept for understanding lipoprotein lipase regulation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32(4):161–166. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200410000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2007;56(11):2655–2667. doi: 10.2337/db07-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duvivier BMFM, Schaper NC, Bremers MA, et al. Minimal intensity physical activity (standing and walking) of longer duration improves insulin action and plasma lipids more than shorter periods of moderate to vigorous exercise (cycling) in sedentary subjects when energy expenditure is comparable. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, et al. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003–2006. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(5):590–597. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine JA, Lanningham-Foster LM, McCrady SK, et al. Interindividual variation in posture allocation: possible role in human obesity. Science. 2005;307(5709):584–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1106561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and high risk for diabetes using A1C criteria in the U.S. Population in 1988–2006. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):562–568. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spring B, Schneider K, McFadden HG, et al. Multiple behavior changes in diet and activity: a randomized controlled trial using mobile technology behavior changes in diet and activity. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(10):789–796. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healy GN, Eakin EG, LaMontagne AD, et al. Reducing sitting time in office workers: Short-term efficacy of a multicomponent intervention. Prev Med. 2013;57(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr LJ, Karvinen K, Peavler M, Smith R, Cangelosi K. Multicomponent intervention to reduce daily sedentary time: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Gardiner PA, Eakin EG, Healy GN, et al. Feasibility of reducing older adults’ sedentary time. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans RE, Fawole HO, Sheriff SA, et al. Point-of-choice prompts to reduce sitting time at work: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith A. Pew Internet & American Life Project: Mobile Technology Fact Sheet. 2014; http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/. Accessed 26 March 2014.

- 28.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications. Inc Accelerometer MSSE. 1998;30(5):777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dantzig S, Geleijnse G, Halteren AT. Toward a persuasive mobile application to reduce sedentary behavior. Personal Ubiquit Comput. 2013;17(6):1237–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00779-012-0588-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuhaus, M., et al., Reducing occupational sedentary time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence on activity-permissive workstations. Obes Rev. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Kozey-Keadle S, Libertine A, Staudenmayer J, et al. The feasibility of reducing and measuring sedentary time among overweight, non-exercising office workers. J Obes. 2012;2012:282303. doi: 10.1155/2012/282303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bond DS, Thomas JG, Raynor HA, et al. B-Mobile—a smartphone-based intervention to reduce sedentary time in overweight/obese individuals: a within-subjects experimental trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper A, Sebire S, Montgomery A, et al. Sedentary time, breaks in sedentary time and metabolic variables in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55(3):589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Healy GN, Clark BK, Winkler EAH, et al. Measurement of adults’ sedentary time in population-based studies. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helmerhorst HJF, Wijndaele K, Brage S, et al. Objectively measured sedentary time may predict insulin resistance independent of moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity. Diabetes. 2009;58(8):1776–1779. doi: 10.2337/db08-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorp AA, Healy GN, Owen N, et al. Deleterious associations of sitting time and television viewing time with cardiometabolic risk biomarkers: Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle (AusDiab) study 2004–2005. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):327–334. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]