Abstract

The Escherichia colifadR protein product, a paradigm/prototypical FadR regulator, positively regulates fabA and fabB, the two critical genes for unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) biosynthesis. However the scenario in the other Ɣ–proteobacteria, such as Shewanella with the marine origin, is unusual in that Rodionov and coworkers predicted that only fabA (not fabB) has a binding site for FadR protein. It raised the possibility of fad regulon contraction. Here we report that this is the case. Sequence alignment of the FadR homologs revealed that the N-terminal DNA-binding domain exhibited remarkable similarity, whereas the ligand-accepting motif at C-terminus is relatively-less conserved. The FadR homologue of S. oneidensis (referred to FadR_she) was over-expressed and purified to homogeneity. Integrative evidence obtained by FPLC (fast protein liquid chromatography) and chemical cross-linking analyses elucidated that FadR_she protein can dimerize in solution, whose identity was determined by MALDI-TOF-MS. In vitro data from electrophoretic mobility shift assays suggested that FadR_she is almost functionally-exchangeable/equivalent to E. coli FadR (FadR_ec) in the ability of binding the E. coli fabA (and fabB) promoters. In an agreement with that of E. coli fabA, S. oneidensisfabA promoter bound both FadR_she and FadR_ec, and was disassociated specifically with the FadR regulatory protein upon the addition of long-chain acyl-CoA thioesters. To monitor in vivo effect exerted by FadR on Shewanella fabA expression, the native promoter of S. oneidensisfabA was fused to a LacZ reporter gene to engineer a chromosome fabA-lacZ transcriptional fusion in E. coli. As anticipated, the removal of fadR gene gave about 2-fold decrement of ShewanellafabA expression by β-gal activity, which is almost identical to the inhibitory level by the addition of oleate. Therefore, we concluded that fabA is contracted to be the only one member of fad regulon in the context of fatty acid synthesis in the marine bacteria Shewanella genus.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0172-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEYWORDS: FadR, fad regulon, fabA, fabB, contraction, Shewanella

INTRODUCTION

Current knowledge on the regulation of fatty acid metabolism is mostly from studies with Escherichia coli (E. coli). The E. coli FadR regulatory protein that is classified into the GntR family of transcription factors, acts as a global regulator controlling bacterial lipid metabolism (Henry & Cronan, 1992, Iram & Cronan, 2005). The two opposite roles played by this regulator include repression of fatty acid degradation (fad) system (Feng & Cronan, 2009b, Henry & Cronan, 1991, Iram & Cronan, 2005), and activation of fabA and fabB, the two genes for unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (Feng & Cronan, 2009a, Henry & Cronan, 1992, Nunn et al., 1983). In fact, the E. coli FadR also indirectly regulates transcription of the glyoxylate bypass operon (aceBAK), through direct activating the IclR repressor (Gui et al., 1996). Very recently, My et al. (My et al., 2013) reported that E. colifabH is the third gene of fatty acid synthesis pathway that can be positively-regulated by the FadR regulator.

As the paradigm FadR regulator, the E. colifadR protein product behaves as a dimer (van Aalten et al., 2000), and consists of the N-terminal DNA-binding domain (Xu et al., 2001) and the ligand-interacting motif at C-terminus (van Aalten et al., 2001). The accumulated crystal structures of FadR alone and its complex with DNA/acyl-CoA defined clearly the structural basis for FadR-mediated regulatory mechanism in the context of lipid metabolism (van Aalten et al., 2001, van Aalten et al., 2000, Xu et al., 2001). In addition to the residues directly contacting target DNA (Xu et al., 2001), we also mapped three more key residues with indirect role in FadR-DNA interplay (Zhang et al., 2014). In vitro and in vivo evidence proved that long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) acyl-CoA thioesters are small molecule effectors for the FadR regulatory system (Henry & Cronan, 1992, van Aalten et al., 2001, Cronan, 1997). The mechanism by which LCFA induces fad expression lies in the fact that the binding of LCFA acyl-CoA to FadR protein results in the alteration of protein configuration, which in turn triggers the loss of its DNA binding ability. However, it still remains unclear why the unexpected functional diversity exists amongst the FadR regulatory proteins (Iram & Cronan, 2005). Of particular note, it is mystery that in relative to the prototypical FadR with an origin of E. coli, the Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) FadR is strikingly superior to in the regulatory amplitude, and bound its ligands appreciably stronger (Iram & Cronan, 2005). Further sequence analyses revealed that an extra 40-aa longer region present in V. cholerae FadR might explain the excellent performance of its regulation role in the context of lipid metabolism (Zhang et al., 2014). Unlike the scenario seen with its closely-relative V. cholerae, the FadR homologue from the other marine bacterium Shewanella, is quite similar to that of the paradigm organism E. coli.

The genus of Shewanella is a family of Gram-negative bacteria inhabiting in marine environment/ecosystem, including no less than 50 diversified species such as S. oneidensis and S. algae (Janda & Abbott, 2014). S. oneidensis is referred to an alternative model anaerobic micro-organism with the known genome sequence (~4.9 Mb) that encodes over 4700 genes (Kolker et al., 2005, Heidelberg et al., 2002). Not only do the species of Shewanella bacteria (e.g., S.putrefaciens) act as normal components of the surface flora of fish and are involved in the spoilage of aquatic products (Parlapani et al., 2013, Li et al., 2012), but also some species like S. algae is recognized to be zoonotic pathogens in that they can cause opportunistic infections via occupational exposure of workers with skin and soft tissue cuts to marine products (Janda & Abbott, 2014). Given the excellent performance of S. oneidensis in reduction of poisonous heavy metals like iron (Cheng et al., 2013), uranium (Sheng & Fein, 2014), and even ionic mercury (Wiatrowski et al., 2006), it was believed to have the robust/potential applications into environmental bioremediation targeting toxic elements and heavy metals and development of microbial fuel cells (Fredrickson et al., 2008, Hau & Gralnick, 2007). The advantage of Shewanella in biotechnology is mainly attributed to the diversified metabolic capabilities that included versatile electron-transfer systems (Hau & Gralnick, 2007, Fredrickson et al., 2008). The deep-sea environment with low temperature where the Shewanella bacteria naturally reside/inhabit determined that some special mechanism might be evolved for their survival. Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2009) found that Shewanella has appreciable ability to produce various types of low-melting-point fatty acids with monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) included. The similar scenario was also noted in the other marine bacterium V. cholerae, in which relatively-high percentage of unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) is present in relative to E. coli (Massengo-Tiasse & Cronan, 2008, Feng & Cronan, 2011a). The physiological explanation proposed lies in that the high percentage of UFA in the bacterial membrane incorporated with phospholipid confers the better membrane fluidity, which in turn enhances its capability of cold adaptation. Although the type II fatty acid synthesis (FAS) pathway in Shewanella was constructed using the approach of comparative genomics (Wang et al., 2009), it seemed likely that some unusual/unclear aspects are present in the regulation of this specialized Type II FAS (Rodionov et al., 2011). Of particular note, Rodionov and coworkers (Rodionov et al., 2011) predicted that only fabA (not fabB) of Shewanella has a binding site for FadR protein, posing the possibility of fad regulon contraction.

In this paper, we integrated in vitro and in vivo approaches to address this uncommon question and reported that this is the case. As expected, Shewanella FadR regulates expression of fabA (not fabB) through the direct protein-DNA physical interplay. Therefore, it is reasonable that the fabA fatty acid synthesis gene is contracted as the only one member of fad regulon in the context of fatty acid synthesis in the marine bacteria Shewanella genus.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Contraction of fad regulon in Shewanella

Different from the paradigm enteric bacterium E. coli that has only one chromosome of 4.64 Mb with average GC contents of, 50.8% and encodes 4498 putative genes (Blattner et al., 1997), S. oneidensis MR-1, the representative cousin with marine origin, not only has a chromosome (4.96 Mb, 46% GC percentage) encoding 4403 genes, but also contains a mega-plasmid (0.16 Mb, 43.7% GC percentage) encoding 149 putative proteins (Heidelberg et al., 2002, Kolker et al., 2005). The similar scenario was also seen with V. cholerae N16961, its closely-relative with the same marine origin, in that it carries two genomes (one of which is 2.98 Mb with 47.7% GC contents and encodes 2690 genes, and other one is 1.07 Mb (46.9% GC percentage) corresponding to 1003 genes (Heidelberg et al., 2000).

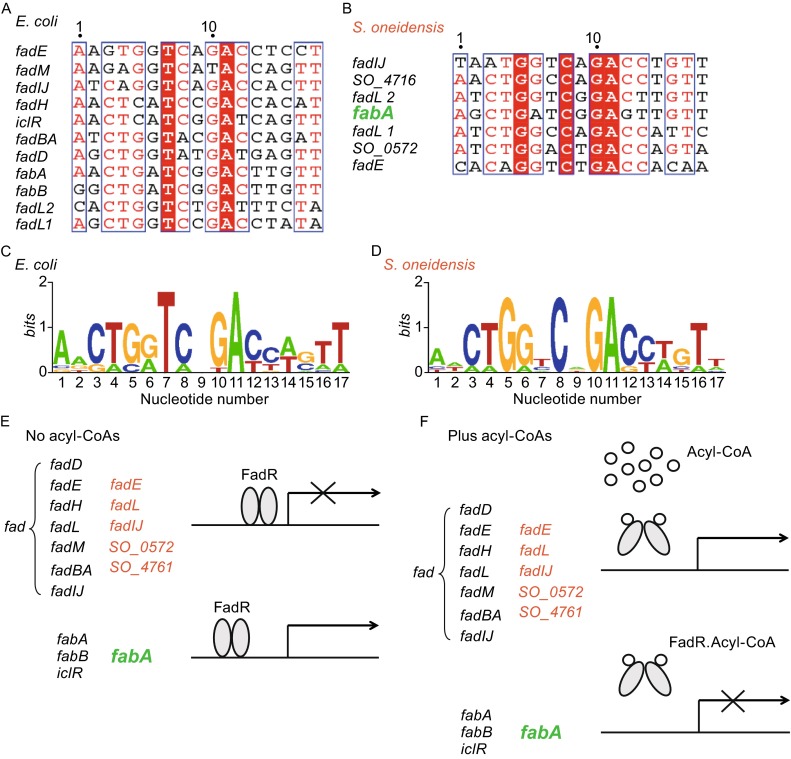

In relative to E. coli that has no less than 12 fad members, those genes controlled by the fatty acid-responsive FadR regulator (Fig. 1A, 1C and 1E), the fad members seemed to be contracted in the cousin S. oneidensis in that only 4 well-known fad genes/operons (fadE, fadL, fadIJ and fabA) has the putative FadR-binding sites (Fig. 1B, 1D and 1F). Also, S. oneidensis possesses two more new FadR-regulated genes (SO_4761 encoding the GNAT family of Acetyltransferease and SO_0572 representing a possible Enoyl-CoA hydratase (EC 4.2.1.17)) (Fig. 1B and 1F), somewhat suggesting the expansion of limited fad members in this marine bacterium. However, this observation argues the possibility of gene horizontal transfer in that the GC contents of two genes SO_4761 (45.23%) and SO_0572 (46.84%) is similar to that of the whole genome (46%). Unlike E. coli that encodes only one FadL fatty acid transporter (Blattner et al., 1997), S. oneidensis has three FadL-like homologues (FadL-1 (SO_3099, 440 aa), FadL-2 (SO_3276, 311 aa) and FadL-3 (SO_4232, 437 aa)) (Heidelberg et al., 2002), only FadL-1 of which is directly regulated by FadR regulatory protein (Fig. 1B and 1F). This situation seems unusual, but not without any precedent. The similar scenario was observed in V. cholerae, the other marine bacterium since three FadL orthologues are distributed in its two chromosomes (Heidelberg et al., 2000), and only FadL-2 is regulated by FadR repressor (http://regprecise.lbl.gov/RegPrecise/regulon.jsp?regulon_id=16367). It is reasonable that three FadL transporters coupled with one FadD inner-membrane protein (3FadL-1FadD) constitute a more efficient system of fatty acid uptake than the prototypical version of 1FadL-1FadD in E. coli. Unlike the V. cholerae FadL-2 that has only one FadR-recognizable site not shown), S. oneidensis FadL-1 exhibits two tandem FadR-binding sites (Fig. 1B), similar to the scenario seen in E. coli FadL (Fig. 1A). Different from the E. colifadD that also carries two tandem FadR-specific palindromes, the fadD gene with origins of both S. oneidensis and V. cholerae seems not to be regulated by the FadR regulator in that the typical site is cryptic (Fig. 1B). In views of genomic evolutions, we anticipated that S. oneidensis has the relics of both E. coli and Vibrio in the context of fatty acid transporter system.

Figure 1.

The working model proposed for fad regulon and its regulation in Shewanella genus. Multiple sequence alignments (A) and sequence logo (C) of the known palindromes recognized by E. coli FadR. Sequence analyses (B) and sequence logo (D) of the predicted FadR-binding sites of Shewanella. The alignment of DNA sequences was carried out using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html), and the output was given via processing with the program ESPript 2.2. (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi) (Feng & Cronan, 2011b). Identical residues are in white letters with red background, similar residues are in the form with mixture of red/black letters, and the varied residues are in black letters. Sequence logo of the FadR-binding sites was generated using the program of WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi). The sequences of the known E. coli FadR sites were sampled from E. coli K-12 MG1655 (http://regprecise.lbl.gov/RegPrecise/regulon.jsp?regulon_id=10286), and the putative Shewanella FadR sites were collected from S. oneidensis MR-1(http://regprecise.lbl.gov/RegPrecise/regulon.jsp?regulon_id=5431). (E) In the absence of a long chain acyl-CoA, E. coli FadR of E. coli and S. oneidensis represses the fad regulon genes, whereas it activates transcription of fabA (and/or fabB) with critical roles in the unsaturated fatty acid synthetic pathway. (F) Binding of long chain acyl-CoA species leads to the release of FadR protein from its operator sites. The fad members of Shewanella are in red except that fabA is highlighted in green. Such kind of FadR-DNA dissociation increases fad regulon expression whereas reduces the expression of fabA (and/or fabB). The oval denotes FadR regulatory protein whereas the small open circle represents the acyl-CoA pool

Given the significant difference of their inhabiting environments/ecological niches (E. coli is enteric bacterium living in fatty acids-rich gastro-intestine, whereas Vibrio and Shewanella both inhabit in the environment of fresh/salt water with poor fatty acids (Giles et al., 2011).), we believed that this kind of fatty acid uptake system might represent an evolutional/physiological advantage for these marine bacteria to scavenge the limited availability of exogenous fatty acids. Intriguingly, comparative analyses of the GC percentage, an indicator of gene horizontal transfer, showed that FadL-2 (48.61%) is appreciably lower than the average value of the whole genome (46%), implying it might be obtained by gene horizontal transfer, whereas FadL-1 (45.43%) and FadL-3 (46.73%) not (not shown).

In generally consistence with the earlier observations with V. cholerae (Feng & Cronan, 2011a, Rodionov et al., 2011), we noted that only the fabA gene from the FabA-FabB UFA synthesis pathway in Shewanella has a known FadR-binding site (Figs. 1B and S1A), whereas the fabB gene does not (Fig. S1B). It suggested the presence of an asymmetric/unparalleled FadR regulation in Shewanella (Fig. 1E and 1F). these findings might argue the conclusions by Shi and coauthors (Shi et al., 2015) in the case of the regulated-expression of the fabB gene in its closely-relative, V. cholerae, in that only indirect role of FadR can be assigned due to the absence of the FadR-binding site. Our observations plus the predictions by Rodionov et al. (Rodionov et al., 2011), supported the proposal that the fad regulon contraction is present in Shewanella. Given the important physiological role of the fabA gene in bacterial UFA synthesis, we attempted to experimentally verify this unusual hypothesis.

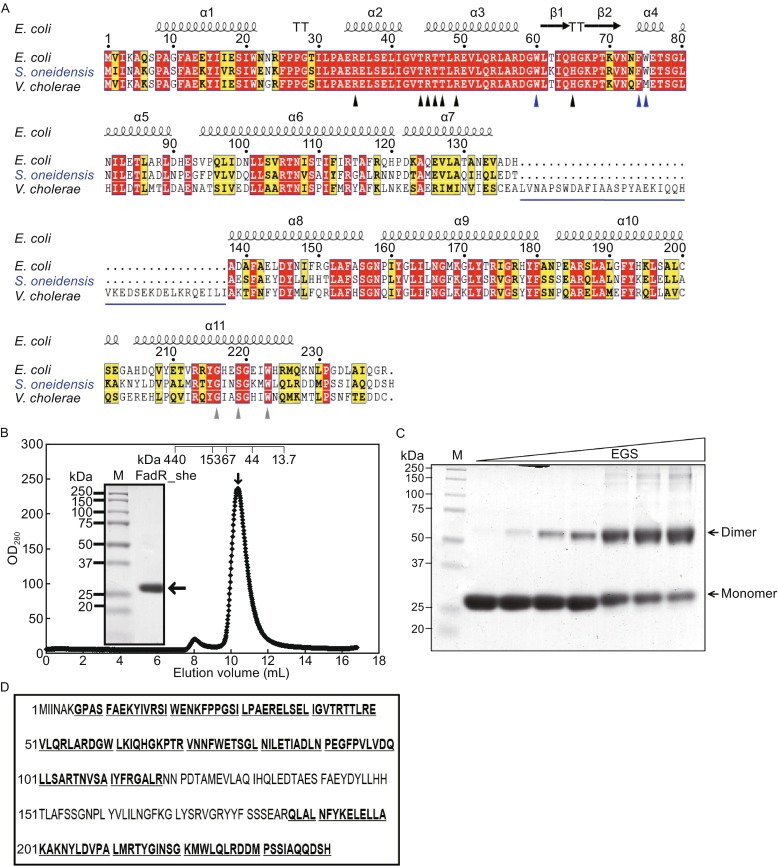

Characterization of Shewanella FadR

An earlier study (Iram & Cronan, 2005) has found that the FadR lipid metabolism regulator of V. cholerae has an unusual insert of 40 residues. Our results (submitted) plus Shi’s observations (Shi et al., 2015) revealed an unexpected contribution of this unique inserting sequence in constituting an extra-ligand binding motif for FadR regulatory protein. The second ligand-binding site confers its excellent ability in fatty acid sensing. Given the fact that both V. cholerae and S. oneidensis are closely-related marine bacteria that shared a similar ecological niche with poor availability of fatty acids, we initially anticipated that this insert might be an indicator or relic for such kind of unparalleled regulation by FadR (Fig. 1). In fact, it is not this case. Multiple sequence alignments of three FadR proteins (FadR_ec for E. coli, FadR_vc for V. cholerae, and FadR_she for S. oneidensis) showed that: 1) the N-terminal DNA-binding motifs are very conserved featuring a full set of all the known residues critical for DNA binding; 2) the C-terminal ligand-interacting domains are appreciably diversified; and 3) the so-called insert of 40 residues (138–177 aa) is only present in FadR_vc (Fig. 2A). Considered the fact combined with atypical features seemed in fatty acid transport system, we favored the anticipation that Shewanella somewhat retains the evolutional relic that are partially observed with E. coli and Vibrio, respectively.

Figure 2.

Characterization of S. oneidensis FadR protein. (A) Sequence analyses of three different FadR homologues. The multiple alignments of FadR protein sequences were performed using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html), and the resultant output was processed by program ESPript 2.2 (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi), generating the final BLAST photography (Feng & Cronan, 2011b). Identical residues are in white letters with red background, similar residues are in black letters in yellow background, the varied residues are in grey letters, and gaps are denoted with dots. In light of the structural architecture of E. coli FadR protein (PDB:1E2X) (van Aalten et al., 2000), the protein secondary structure was illustrated in cartoon (on top) (Zhang et al., 2014), α: alpha-helix; β: beta-sheet; T: Turn; η: coil. The seven known DNA-binding sites (R35, T44, R45, T46, T47, R49 and 65H) are highlighted with black triangles (Xu et al., 2001), the three known ligand-binding sites are shown with grey triangles (216G, 219S and 223W) (van Aalten et al., 2001), and the newly-proposed amino acids with indirect role for FadR-DNA interaction are highlighted with blue arrows (W60, F74 and W75) (Zhang et al., 2014). The extra 40-aa (138–177) longer region of V. cholerae FadR was underlined in blue. The FadR sequences are separately sampled from E. coli K12 (Accession no.: CAA30881), V. cholerae (Vibrio cholerae) (Accession no.: AAO37924) and S. oneidensis (Accession no.: NP_718457). (B) Gel exclusion chromatographic profile of the recombinant S. oneidensis FadR protein run on a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare). The expected peak of the target FadR was eluted at the position of 10.5 mL (highlighted with an arrow). The inset gel is the 15% SDS-PAGE photography of the collected S. oneidensis FadR protein sample. The mass of the monomeric S. oneidensis FadR is estimated to be ∼27 kDa. Abbreviations: M, protein marker; OD280, optical density at 280 nm; mAu, milli-absorbance units. The ruler on the top was given to describe the elution pattern of the standard proteins (Pharmacia). The standards used here included Ferritin (∼440 kDa), Aldolase (153 kDa), Bovine serum albumin (∼67 kDa), Ovalbumin (∼44 kDa) and ribonuclease (∼13.7 kDa), respectively. (C) Chemical cross-linking analyses for the purified S. oneidensis FadR protein. The level of EGS chemical cross-linker was illustrated with a triangle varies from 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, to 2.0 µmol/L. (D) MS determination of the recombinant S. oneidensis FadR protein. The matched amino acid residues that exhibited 69% coverage to the native S. oneidensis FadR are given bold and underlined type

To further functional analyses of the above bacterial FadR proteins, we over-expressed the three types of recombinant FadR proteins (FadR_ec FadR_vc & FadR_she) and purified them to homogeneity. As expected, SDS-PAGE profile clearly showed the purified FadR_she protein migrates at the position of ~27 kDa. The FPLC profile showed that the expected peak of purified S. oneidensis FadR was eluted at the position of 10.5 mL (indicated with an arrow, Fig. 2B), suggesting its apparent molecular mass is more than 44 kDa, but less than 67 kDa. Given the fact that the ideal molecular weight of recombinant S. oneidensis FadR in momomer is ~27 kDa, we believed that the form of FadR_she in solution might be a dimer (-54 kDa). It was generally consistent with the scenario seen with the E. coli FadR as a dimer. Subsequently, we used chemical cross-linking assays to further prove this speculation. As we expected, appearance/formation of the dimerization for the FadR_she protein is appreciably increased upon addition of chemical cross-linker EGS (Fig. 2C). Also, it behaves in an EGS dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). In particular, the dimer band was excised from the SDS-PAGE and subjected to liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. As a result, the MS results confirmed this identity in that the digested peptides matched the S. oneidensis FadR protein with the coverage of 69% (Fig. 2D).

The FadR proteins of E. coli and S. oneidensis are functionally-equivalent

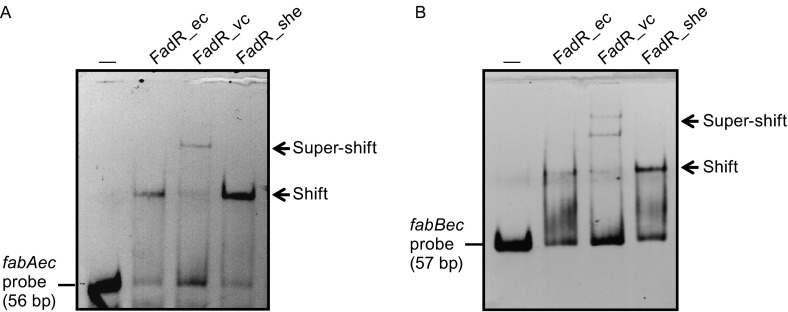

Gel shift assay was performed to detect the binding ability of FadR_ec, FadR_vc and FadR_she to the cognate DNA binding sites. As expected, EMSA-based experiments showed that the E. coli FadR protein (as the positive control) binds well to its own promoters of both fabA (Fig. 3A) and fabB (Fig. 3B) promoters. The fact that the FadR_vc protein gives consistently the super-shift bands for both fabA and fabB probes in the gel shift assays, is mostly attributed to the essence of its easy-forming the protein multimer (Fig. 3). Of note, FadR_she exhibited an excellent ability of interacting with the fabA (Fig. 3A) and fabB (Fig. 3B) with the origin of E. coli. It seemed likely that the FadR proteins of E. coli and S. oneidensis are functionally-equivalent (and/or exchangeable). It is not surprise since the FadR/FabR orthologue from other marine bacterium, Vibrio, also followed this rule (Feng & Cronan, 2011b, Feng & Cronan, 2011a). To our knowledge, the cases of similar functional exchange of transcriptional regulators can be extended to BioR, the other GntR-type regulators implicated into the metabolism of biotin, a sulfur-containing fatty acid (Feng et al., 2013a, Feng et al., 2013b). Thereby, it makes sense that the atypical regulation by FadR in UFA synthesis of Shewanella is due to the cryptic site in front of fabB (Fig. 1), not FadR_she (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Shewanella FadR protein is functionally-exchangeable to the paradigm E. coli version. (A) EMSA-based evidence for binding of E. coli fabA promoter to FadR protein of three origins. (B) EMSA analyses for crosstalk of E. coli fabA promoter with three kinds of bacterial FadR proteins. A representative photography was given here, which were from no less than three independent EMSA experiments (7% native PAGE). Three versions of FadR protein here are FadR_ec, FadR_vc and FadR_she, respectively. In gel shift assays, the FadR protein (5 pmol) is incubated with DIG-labeled fabAec (or fabBec) probe (0.2 pmol). Note: An unexpected but interesting scenario “super-shift” is consistently observed in our trials with V. cholerae FadR

S. oneidensis fabA has a functional FadR-binding site, and this binding is specifically reversed by long-chain acyl-CoA

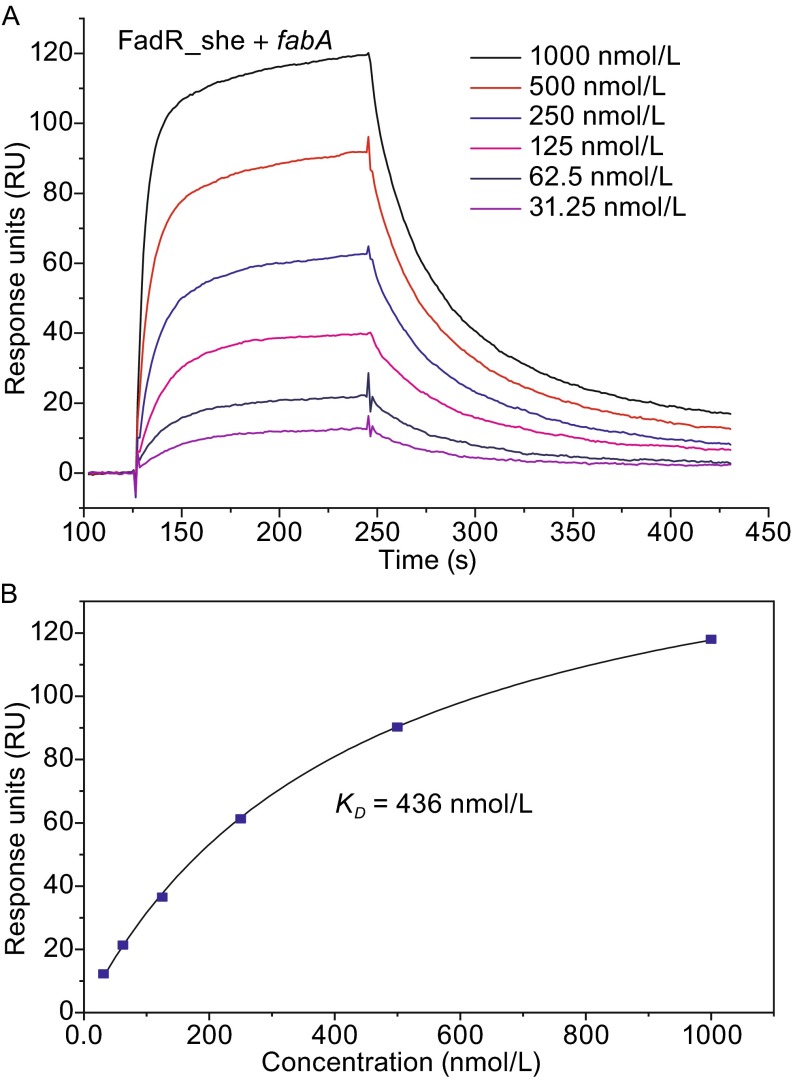

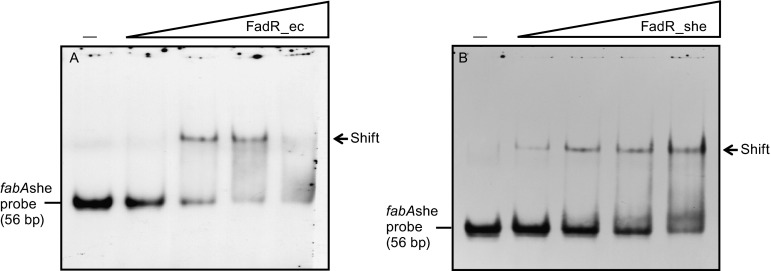

Through sequence comparison of the fabA and fabB promoter regions of E. coli, V. cholerae and S. oneidensis, we found that the cognate FadR-specific binding site in front of the fabA promoter regions of these three bacterial species are much more conservative (Fig. S1A), but that of fabB promoter region is not (Fig. S1B). This observation is generally consistent with the prediction by Rodionov and coworkers (Rodionov et al., 2011) that only fabA (not fabB) of Shewanella has a binding site for the FadR regulator. To further prove the function of this predicted site, termed fabA probe, we synthesized it using the approach of annealing the two complementary DNA strand. This DNA probe is digoxigenin-labeled DNA fragment of 56 bp that overlaps the candidate FadR_she binding site (Fig. S1A and Table 2). Gel shift assays confirmed that FadR_ec (Fig. 4A) and FadR_she (Fig. 4B) both can efficiently bind the S. oneidensisfabA promoter. In much similarity to the scenario seen with FadR_ec here (Fig. 4A), plus our former observations with FadR regulators of E. coli (Feng & Cronan, 2009b, Feng & Cronan, 2010) and V. cholerae (Feng & Cronan, 2011b), we also found that the fabA_she probe binds FadR_she protein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). To preliminarily elucidate the kinetics of FadR_she/fabA_she interaction, we conducted surface plasom resonance (SPR)-based measurements. SPR results revealed that the binding affinity (KD) of fabA_she to FadR_she is roughly 436 nmol/L (Fig. 5A and 5B), and the binding mode is 2:1 (a dimeric FadR protein is bound to a target DNA fragment (not shown).

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primers | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| fadR_she-F | 5′-CG GGATCC ATG ATT ATC AAT GCC AAA GGA CC-3′ |

| fadR_she-R | 5′-CCG CTCGAG CTA ATG GGA GTC CTG CTG TG-3′ |

| fabR_she-F | 5′-CG GGATCC ATG GGT ATT CGT GCA CAG CA-3′ |

| fabR_she-R | 5′-CCG CTCGAG CTA CCG ATG TTC AAC TTT ATG T-3′ |

| fabA_she-BD-F | 5′-GAC ATT AAT TAG CTG ATC GGA GTT GTT TAG CTT ACA CGT GTT CGC TAA TCT TGG CG-3′ |

| fabA_she-BD-R | 5′-CGC CAA GAT TAG CGA ACA CGT GTA AGC TAA ACA ACT CCG ATC AGC TAA TTA ATG TC-3′ |

| fabA_ec-BD-F | 5′-TTT ATT CCG AAC TGA TCG GAC TTG TTC AGC GTA CAC GTG TTA GCT ATC CTG CGT GC-3′ |

| fabA_ec-BD-R | 5′- GCA CGC AGG ATA GCT AAC ACG TGT ACG CTG AAC AAG TCC GAT CAG TTC GGA ATA AA-3′ |

| fabB_ec-BD-F | 5′-TCT ATT AAA TGG CTG ATC GGA CTT GTT CGG CGT ACA AGT GTA CGC TAT TGT GCA TTC-3′ |

| fabB_ec-BD-F | 5′-GAA TGC ACA ATA GCG TAC ACT TGT ACG CCG AAC AAG TCC GAT CAG CCA TTT AAT AGA -3′ |

| PfabAshe-F | 5′-CCG GTCGAC GAG GGT TAA CGG GTA AAC AAG-3′ |

| PfabAshe-R | 5′-AACC GAATTC GTC GAT CAT CAG CAT GTT GTC-3′ |

| LacZ-R | 5′-GAC CAT GAT TAC GGA TTC ACT G-3′ |

The sequences underlined are restriction sites. Putative FadR-binding sites are in bold letters, and the predicted FabR palindromes are indicated in bold and italic

Figure 4.

Evidence that Shewanella fabA promoter has a functional FadR-recognizable palindrome. (A) Binding of Shewanella fabA promoter to E. coli FadR protein. (B) Interplay between Shewanella fabA promoter and Shewanella FadR protein. The gel shift tests were conducted using 7% native PAGE, and a representative result is shown here. In these assays, levels of FadR protein (FadR_ec and FadR_she) added are denoted with a triangle on right hand (0.1, 0.5, 2, and 5 pmol), whereas the DIG-labeled fabBshe probe is added to 0.2 pmol. Minus sign denotes no addition of FadR protein

Figure 5.

SPR-based dynamic analyses for binding of fabA to Shewanella FadR. (A) SPR assay for interaction between fabA and FadR_she. (B) Measurement of the KD value for fabA-FadR_she

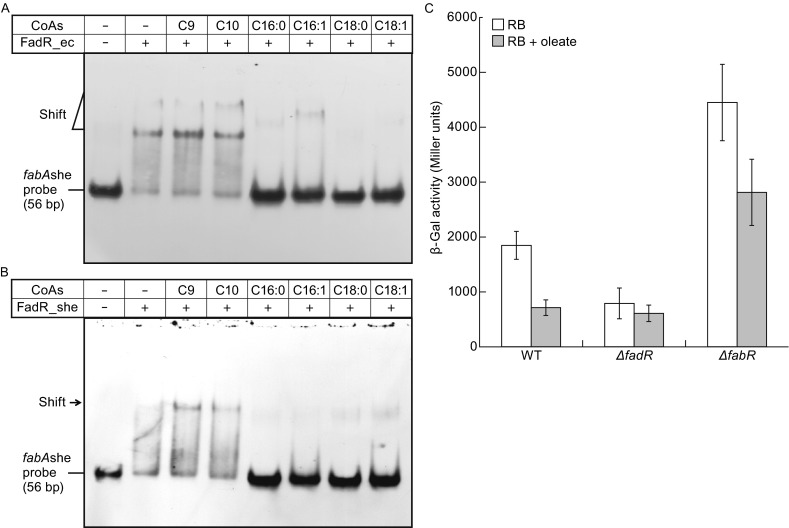

Given the fact that long-chain (but not short chain) fatty acyl-CoA species can antagonize the DNA-binding activity of FadR with origins of E. coli (Henry & Cronan, 1992, Cronan, 1997) and Vibrio (Iram & Cronan, 2005, Feng & Cronan, 2011b), it is of much interest to test the behaviors of theses ligands in the case of S. oneidensis FadR. Therefore, we tested six acyl-CoA species of different acyl chain lengths. The EMSA-based competition assays showed that medium-chain acyl-CoA (C9:0; C10:0) don’t interfere with the fabA_she binding to either FadR_ec (Fig. 6A) or FadR_she (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the long-chain acyl-CoA species (C16:0, C16:1, C18: 0 and C18:1) strongly impaired DNA binding (Fig. 6A and 6B). We believed that long-chain but not medium-chain acyl-CoA can specifically interact with FadR_she ligand-binding site and release FadR_she from the S. oneidensisfabA promoter. In summary, the in vitro data accumulated suggest that long-chain acyl-CoAs regulate the Shewanella fabA transcription via their interaction with the FadR protein.

Figure 6.

Role of LC fatty acyl-CoA in fabA expression in vitro and in vivo. (A) EMSA-based visualization for effects of medium and long chain acyl-CoA species on binding of FadR_ec to the fabAshe probe. (B) Effects of different long chain acyl-CoA species on binding of FadR_she to the fabAshe probe. In the binding reaction mixtures (10 µL in total), the FadR (~5 pmol) was incubated with 0.2 pmol of DIG-labeled fabAshe probe. When required, acyl-CoA (~50 pmol) was added as we recently described (Feng & Cronan, 2011b). The gel shift assays were conducted for more than three times using 7% native PAGE, and the representative result is given. The shifted fabAshe probe band is indicated with a triangle (A) or an arrow (B). Designations C9:0, nonanoyl-CoA; C10:0, decanoyl-CoA; C16:0, palmitoyl-CoA; C18:0, stearoyl-CoA; C18:1, oleoyl-CoA. Abbreviations: ec and she denote E. coli and Shewanella, respectively. Plus sign denotes addition of either FadR proteins or acyl-CoA species, whereas minus sign denotes no addition of either FadR protein or acyl-CoA species. (C) Transcription of fabAshe is activated by FadR in E. coli and repressed upon oleic acid supplementation. All the E. coli strains used here carried a single copy of fabAshe-lacZ transcriptional fusion which is integrated on chromosomes. Bacterial cultures in mid-log phase were collected for assaying the LacZ (β-gal) activity. The three strains used here included FYJ241 (WT), FYJ246 (ΔfadR), and FYJ247 (ΔfabR), respectively. As anticipated, transcription of fabA she is also negatively regulated by FabR in E. coli

Expression of Shewanella fabA is activated by FadR, but repressed by oleate in E. coli

It is well known that: 1) FadR acts as an activator for expression of fabA and fabB, the two genes required for E. coli UFA synthesis, 2) whereas FabR is a repressor for expression of fabA and fabB. We construct three E. coli strains including FYJ241 (WT), FYJ246 (△fadR) and FYJ247 (△fabR). The three strains all carried a single copy of fabAshe-lacZ transcriptional fusion on chromosomes which allows us to detect whether the E. coli counterpart of FadR regulatory proteins has the in vivo role in modulating the ShewanellafabA expression and to monitor the physiological effect on fabA_she transcription exerted by exogenous fatty acids. Measurement of the β-Gal levels of these strains showed that deletion of fadR eliminate its activation to fabA_she expression (Fig. 6C). In comparison with the wild-type strain, appreciable lower β-gal activity was seen in the △fadR mutant (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the removal of the opposite regulator, FabR repressor, gave significant increment of fabA_she expression (Fig. 6C). As expected, the activity of fabA_she promoter is inhibited by the addition of oleate and this down-regulation is dependent on the presence of FadR regulator (Fig. 6C). Thus, our results represent in vivo evidence that expression of Shewanella fabA is activated by FadR, but repressed by oleate.

CONCLUSIONS

The data reported here defined that the Shewanella FadR homologue is a functional regulator with the involvement of fatty acid metabolism. Also, we experimentally proved the proposal by Rodionov et al. (Rodionov et al., 2011) that fad regulon is contracted in Shewanella. Retrospectively, Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2009) reported the pilot exploration of fatty acid metabolism in Shewanella piezotolerans with concentration on its relevance to different temperatures and pressures.

Very recently, Gao’s research group also provided genetic evidence in aiming to pose its role of fadR into the UFA pathway in S. oneidensis MR-1 (Luo et al., 2014). Right now, the picture of Shewanella FadR seemed to be much more complete in the context of lipid metabolism. Unlike the paradigm E. coli in which both fabA and fabB have the FadR-binding sites, Shewanella only rendered the fabA fatty acid synthesis gene under the control by the FadR activator (Figs. 1 and 6C) and the FabR repressor (Fig. 6C). Moreover, it is in rational to functionally assign this unparalleled regulation to its unique evolutional selection and even adaptation to its growing (/neighboring) environmental/ecological niches with the availability of limited fatty acids. Taken together, we provided integrative evidence that Shewanella FadR binds to the fabA fatty acid biosynthetic gene, which is implicated into contraction of the fad regulon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

With an exception of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (S. oneidensis), all of the bacterial strains used here were E. coli K-12 derivatives (Table 1). The media are separately LB medium (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract and 10 g of NaCl per liter), and rich broth (RBO medium;10 g of tryptone, 1 g of yeast extract and 5 g of NaCl per liter). To measure the activity of β-galactosidase in induction assays, oleate was solubilized with Tergitol NP-40 and used at a 5 mmol/L final concentration. Antibiotics were supplemented as follows (in mg/L): sodium ampicillin, 100; kanamycin sulfate, 50; tetracycline HCl, 15; and chloramphenicol, 20.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacteria or plasmids | Relevant characteristics | Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||||

| Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 | A Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria which is predominantly found in deep sea anaerobic habitats | Heidelberg et al. (2002), CGSCa | ||

| BL21(DE3) | An expression host for recombinant plasmids | Lab stock | ||

| MFH8 | UB1005, ΔfadR::Tn10 | Henry & Cronan (1992) | ||

| SI91 | UB1005, ΔfabR::Cm | Feng & Cronan (2009b) | ||

| FYJ187 | MC4100/pINTts | Feng & Cronan (2011b) | ||

| FYJ189 | BL21 carrying pET28a-fabRshe | This work | ||

| FYJ214 | BL21 carrying pET28a-fadRshe | This work | ||

| FYJ193 | DH5α (λ-pir) | Lab stock, (Feng & Cronan, 2009a, Feng & Cronan, 2011b) | ||

| FYJ236 | DH5α (λ-pir) carrying pAH-PfabAshe | This work | ||

| FYJ241 | MC4100 with a single copy of fabAshe-lacZ fusion integrated at the λ-site | This work | ||

| FYJ246 | FYJ241, ΔfadR : Tn10 | FYJ241/P1 vir(MFH8) | ||

| FYJ247 | FYJ241, ΔfabR : Cm | FYJ241/P1 vir(SI91) | ||

| Plasmids | ||||

| pET28(a) | T7 promoter-driven expression vector, KanR | Novagen | ||

| pAH125 | Promoter-less lacZ reporter plasmid in E. coli, KanR | Feng & Cronan (2009a), Haldimann & Wanner (2001) | ||

| pET28-fadRec | Recombinant plasmid carrying E. coli fadR, KanR | Cherepanov & Wackernagel (1995), Feng & Cronan (2009b), Feng & Cronan (2009a) | ||

| pET16-fadRvc | Recombinant plasmid carrying V. cholerae fadR, KanR | Feng & Cronan (2011b), Iram & Cronan (2005) | ||

| pET28-fadRshe | Recombinant plasmid carrying Shewalle fadR, KanR | This work | ||

| pAH-PfabAshe | Recombinant plasmid carrying Shewalle fabA promoter region, KanR | This work | ||

aCGSC denotes Coli Genetic Stock Center, Yale University

Plasmids and DNA manipulations

The fabA promoter region of S. oneidensis was PCR amplified and directly cloned into pAH125, giving the recombinant plasmid pAH125-PfabAshe (Table 1). Similarly, the fadR gene amplified from S. oneidensis was inserted into expression vector pET28(a), generating the chimeric plasmid pET28-fadRshe (Table 2). To prepare three different versions of FadR proteins, the corresponding expression plasmids (pET28-fadRec, pET28-fadRshe and pET16-fadRvc, in Table 2) were transformed into the strain BL21(DE3) (Feng & Cronan, 2009b). The acquired plasmids were verified by direct DNA sequencing.

Given that the replication of pAH-PfabAshe plasmid requires the presence of pir protein, it thus was maintained in strain DH5α λ-pir (Table 1). To impart antibiotic resistance in E. coli MC4100 (a lacZ strain lacking pir), this plasmid must specifically integrate into the attλ site of bacterial chromosome in a reaction catalyzed by the pINT-ts helper plasmid, giving strain FYJ241 carrying fabAshe-lacZ transcriptional fusion (Table 1). PCR assay was applied to confirm the fabAshe-lacZ junction.

P1vir phage transductions

P1vir transductions were conducted as described by Miller (Miller, 1992) with little changes. The strain FYJ246 was constructed by P1vir transduction of strain FYJ241 using a lysate grown on strain MFH8 (ΔfadR::Tn10) with selection for tetracycline resistance. Similarly, strain FYJ241 was transduced by P1vir lysate obtained from strain SI91 (ΔfabR::Cm) with selection for kanamycin, giving strain FYJ247 (Table 1). The relevant genotypes of the acquired strains were proved by PCR analyses.

β-Galactosidase assays

Mid-log phase cultures grown in either LB or RB were collected by spinning, washed with Z-buffer and suspended in Z-buffer for further measurement of β-galactosidase activity (Feng & Cronan, 2009b, Feng & Cronan, 2009a, Miller, 1992). The data were recorded in triplicate in no less than three independent assays.

Expression and purification of three different FadR proteins

In addition to the FadR protein with origins of both E. coli and V. cholerae, the S. oneidensis FadR protein was produced in solubility via the induced expression with 0.2 mmol/L isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 30°C for 3.5 h. The bacterial lysis by two rounds of sonication treatment was clarified by centrifugation, and the resultant supernatant was loaded onto a nickel-ion affinity column (Qiagen). The contaminant proteins were removed with wash buffer containing 50 mmol/L imidazole, and subsequently the 6× His-tagged FadR proteins in three versions (FadR_she, FadR_ec and FadR_vc) were eluted in elution buffer containing 100 mmol/L imidazole. The protein was concentrated by ultra-filtration (30 kDa cutoff) and exchanged into 1× PBS buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10% glycerol. The purified proteins were visualized by 15% SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Size exclusion chromatography

Given the fact that both FadR_ec and FadR_vc can form dimer, we aimed to check the solution structure of FadR_she. Therefore, we used a Superdex 75 column (Pharmacia) run on an Äkta fast protein liquid chromatography system (GE Healthcare) (Feng & Cronan, 2010, Feng & Cronan, 2011a) to perform gel filtration analyses for the purified FadR_she protein. In our trials, the column effluent was monitored at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min in running buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 50 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.9). The peaks of interest were collected and confirmed with 15% SDS-PAGE.

Liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry

The identity of the recombinant FadR_she protein we produced was confirmed using A Waters Q-Tof API-US Quad-ToF mass spectrometer connected to a Waters nano Acquity UPLC) (Feng & Cronan, 2011a). In brief, the protein band of interest was cut from 15% SDS-PAGE gel, de-stained and digested with Sequencing Grade Trypsin (G-Biosciences St. Louis, MO, 12.5 ng/μL in 25 mmol/L ammonium bicarbonate); Second, the resulting peptides were loaded on a Waters Atlantis C-18 column (0.03 mm particle, 0.075 mm × 150 mm), following the further cleaning treatment. The data dependent acquisition combined with ms/ms analysis was routinely performed (Feng & Cronan, 2011a).

Chemical cross-linking assays

To further test the solution structure of S. oneidensis FadR, we carried out the experiments of chemical cross-linking with ethylene glycol bis-succinimidylsuccinate (Pierce) as we described before (Feng & Cronan, 2010). In each chemical cross-linking reaction (15 μL in total), the purified FadR protein (~10 mg/mL) was separately mixed with cross-linker at different concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 mmol/L), and kept 30 min at room temperature before analysis. Note: the only protein without EGS addition serves as the negative control. All the reaction products were detected using 15% SDS-PAGE.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

To document the function of FadR-binding site located in the S.oneidensisfabA promoter, gel shift assays were performed as we earlier described (Feng & Cronan, 2009b, Feng & Cronan, 2010, Feng & Cronan, 2011a) with minor modifications. Totally, three sets of DNA probes (Table 2) corresponded to fabAec, fabBec and fabAshe, respectively. They were all generated by annealing two complementary oligonucleotides (e.g., fabA_she-BD-F plus fabA_she-BD-R, in Table 2) through the incubation at 95°C in TEN buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 100 mmol/L NaCl, pH 8.0) for 5 min followed by slow cooling to 25°C. The digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes (~0.2 pmol) were mixed with purified FadR (in appropriate concentrations) in the binding buffer (Roche) and incubated 20 min at room temperature. The DNA/protein mixtures were then analyzed by the native 7% PAGE, and directly transferred onto nylon membrane by contact blotting-aided gel transfer. Following appropriate treatments, the chemical-luminescence signals were captured by an exposure of the membrane to ECL films (Amersham).

Surface plasmon resonance

Biacore3000 instrument (GE Healthcare) was utilized to carry out the surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based measurement. The biotinylated fabA_she DNA probe was immobilized by streptavidin on the chip surface. The SPR assay was run in the running buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mmol/L NaCl and 0.005% Tween 20) at the flow rate of 30 μL/min. FadR_she protein in a series of dilution was injected and passed over the chip surface for 2 min. Kinetic parameters were analyzed using a global data analysis program (BIA evaluation software), and final graph was given with the Origin software.

Bioinformatic analyses

The amino acid sequences of FadR regulator are derived from E. coli, V. cholerae and S. oneidensis MR-1. The FadR-binding sites were all sampled from RegPrecise database (http://regprecise.lbl.gov/RegPrecise/regulon.jsp?). The multiple alignments were conducted using the program of ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html), and the resultant output was further processed by the program ESPript 2.2 (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi), giving the final version of BLAST photography.

Electronic supplementary material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No.: LR15H190001), and the start-up package from Zhejiang University (Y.F.). Dr. Feng is a recipient of the “Young 1000 Talents” Award. We would like thank Mr. Yuan Lin for his help in SPR analyses.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICS GUIDELINES

Huimin Zhang, Beiwen Zheng, Rongsui Gao and Youjun Feng declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FAS

fatty acid synthesis

- FPLC

fast protein liquid chromatography

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- LCFA

long-chain fatty acid

- UFA

unsaturated fatty acid

Footnotes

Huimin Zhang and Beiwen Zheng have contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G, 3rd, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YY, Li BB, Li DB, Chen JJ, Li WW, Tong ZH, Wu C, Yu HQ. Promotion of iron oxide reduction and extracellular electron transfer in Shewanella oneidensis by DMSO. PloS one. 2013;8:e78466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene. 1995;158:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan JE., Jr In vivo evidence that acyl coenzyme A regulates DNA binding by the Escherichia coli FadR global transcription factor. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1819–1823. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1819-1823.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Cronan JE. Escherichia coli unsaturated fatty acid synthesis: complex transcription of the fabA gene and in vivo identification of the essential reaction catalyzed by FabB. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29526–29535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Cronan JE. A new member of the Escherichia coli fad regulon: transcriptional regulation of fadM (ybaW) J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6320–6328. doi: 10.1128/JB.00835-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Cronan JE. Overlapping repressor binding sites result in additive regulation of Escherichia coli FadH by FadR and ArcA. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:4289–4299. doi: 10.1128/JB.00516-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Cronan JE. Complex binding of the FabR repressor of bacterial unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis to its cognate promoters. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:195–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Cronan JE. The Vibrio cholerae fatty acid regulatory protein, FadR, represses transcription of plsB, the gene encoding the first enzyme of membrane phospholipid biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:1020–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Xu J, Zhang H, Chen Z, Srinivas S. Brucella BioR regulator defines a complex regulatory mechanism for bacterial biotin metabolism. J bacteriol. 2013;195:3451–3467. doi: 10.1128/JB.00378-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Zhang H, Cronan JE. Profligate biotin synthesis in alpha-proteobacteria—a developing or degenerating regulatory system? Mol Microbiol. 2013;88:77–92. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson JK, Romine MF, Beliaev AS, Auchtung JM, Driscoll ME, Gardner TS, Nealson KH, Osterman AL, Pinchuk G, Reed JL, Rodionov DA, Rodrigues JL, Saffarini DA, Serres MH, Spormann AM, Zhulin IB, Tiedje JM. Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2008;6:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles DK, Hankins JV, Guan Z, Trent MS. Remodelling of the Vibrio cholerae membrane by incorporation of exogenous fatty acids from host and aquatic environments. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:716–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui L, Sunnarborg A, LaPorte DC. Regulated expression of a repressor protein: FadR activates iclR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4704–4709. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4704-4709.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldimann A, Wanner BL. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6384–6393. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hau HH, Gralnick JA. Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:237–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam L, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Salzberg SL, Smith HO, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC, Fraser CM. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 2000;406:477–483. doi: 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberg JF, Paulsen IT, Nelson KE, Gaidos EJ, Nelson WC, Read TD, Eisen JA, Seshadri R, Ward N, Methe B, Clayton RA, Meyer T, Tsapin A, Scott J, Beanan M, Brinkac L, Daugherty S, DeBoy RT, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Haft DH, Kolonay JF, Madupu R, Peterson JD, Umayam LA, White O, Wolf AM, Vamathevan J, Weidman J, Impraim M, Lee K, Berry K, Lee C, Mueller J, Khouri H, Gill J, Utterback TR, McDonald LA, Feldblyum TV, Smith HO, Venter JC, Nealson KH, Fraser CM. Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1118–1123. doi: 10.1038/nbt749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry MF, Cronan JE., Jr Escherichia coli transcription factor that both activates fatty acid synthesis and represses fatty acid degradation. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:843–849. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90574-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry MF, Cronan JE., Jr A new mechanism of transcriptional regulation: release of an activator triggered by small molecule binding. Cell. 1992;70:671–679. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90435-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iram SH, Cronan JE. Unexpected functional diversity among FadR fatty acid transcriptional regulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32148–32156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Shewanella: from the briny depths below to human pathogen. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2014;40:293–312. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.726209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolker E, Picone AF, Galperin MY, Romine MF, Higdon R, Makarova KS, Kolker N, Anderson GA, Qiu X, Auberry KJ, Babnigg G, Beliaev AS, Edlefsen P, Elias DA, Gorby YA, Holzman T, Klappenbach JA, Konstantinidis KT, Land ML, Lipton MS, McCue LA, Monroe M, Pasa-Tolic L, Pinchuk G, Purvine S, Serres MH, Tsapin S, Zakrajsek BA, Zhu W, Zhou J, Larimer FW, Lawrence CE, Riley M, Collart FR, Yates JR, 3rd, Smith RD, Giometti CS, Nealson KH, Fredrickson JK, Tiedje JM. Global profiling of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1: expression of hypothetical genes and improved functional annotations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2099–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409111102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ying Q, Su X, Li T. Development and application of reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification for detecting live Shewanella putrefaciens in preserved fish sample. J Food Sci. 2012;77:M226–M230. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q, Shi M, Ren Y, Gao H. Transcription factors FabR and FadR regulate both aerobic and anaerobic pathways for unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Shewanella oneidensis. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:736. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massengo-Tiasse RP, Cronan JE. Vibrio cholerae FabV defines a new class of enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1308–1316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- My L, Rekoske B, Lemke JJ, Viala JP, Gourse RL, Bouveret E. Transcription of the Escherichia coli fatty acid synthesis operon fabHDG is directly activated by FadR and inhibited by ppGpp. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:3784–3795. doi: 10.1128/JB.00384-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn WD, Giffin K, Clark D, Cronan JE., Jr Role for fadR in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:554–560. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.554-560.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlapani FF, Meziti A, Kormas KA, Boziaris IS. Indigenous and spoilage microbiota of farmed sea bream stored in ice identified by phenotypic and 16S rRNA gene analysis. Food Microbiol. 2013;33:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov DA, Novichkov PS, Stavrovskaya ED, Rodionova IA, Li X, Kazanov MD, Ravcheev DA, Gerasimova AV, Kazakov AE, Kovaleva GY, Permina EA, Laikova ON, Overbeek R, Romine MF, Fredrickson JK, Arkin AP, Dubchak I, Osterman AL, Gelfand MS. Comparative genomic reconstruction of transcriptional networks controlling central metabolism in the Shewanella genus. BMC Genom. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, Fein JB. Uranium reduction by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 as a function of NaHCO3 concentration: surface complexation control of reduction kinetics. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:3768–3775. doi: 10.1021/es5003692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Kovacikova G, Lin W, Taylor RK, Skorupski K, Kull FJ. The 40-residue insertion in Vibrio cholerae FadR facilitates binding of an additional fatty acyl-CoA ligand. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6032. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aalten DM, DiRusso CC, Knudsen J, Wierenga RK. Crystal structure of FadR, a fatty acid-responsive transcription factor with a novel acyl coenzyme A-binding fold. EMBO J. 2000;19:5167–5177. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aalten DM, DiRusso CC, Knudsen J. The structural basis of acyl coenzyme A-dependent regulation of the transcription factor FadR. EMBO J. 2001;20:2041–2050. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Xiao X, Ou HY, Gai Y, Wang F. Role and regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in the response of Shewanella piezotolerans WP3 to different temperatures and pressures. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2574–2584. doi: 10.1128/JB.00498-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiatrowski HA, Ward PM, Barkay T. Novel reduction of mercury (II) by mercury-sensitive dissimilatory metal reducing bacteria. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:6690–6696. doi: 10.1021/es061046g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Heath RJ, Li Z, Rock CO, White SW. The FadR.DNA complex. Transcriptional control of fatty acid metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17373–17379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gao R, Ye H, Wang Q, Feng Y. A new glimpse of FadR-DNA crosstalk revealed by deep dissection of the E. coli FadR regulatory protein. Protein Cell. 2014;5:928–939. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0107-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.