Abstract

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is a small virus whose genome has only four open reading frames. We argue that the simplicity of the virion correlates with a complexity of functions for viral proteins. We focus on the HBV core protein (Cp), a small (183 residue) protein that self-assembles to form the viral capsid. However, its functions are a little more complicated than that. In an infected cell Cp modulates every step of the viral lifecycle. Cp is bound to nuclear viral DNA and affects its epigenetics. Cp correlates with RNA specificity. Cp assembles specifically on a reverse transcriptase-viral RNA complex or, apparently, nothing at all. Indeed Cp has been one of the model systems for investigation of virus self-assembly. Cp participates in regulation of reverse transcription. Cp signals completion of reverse transcription to support virus secretion. Cp carries both nuclear localization signals and HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) binding sites; both of these functions appear to be regulated by contents of the capsid. Cp can be targeted by antivirals -- while self-assembly is the most accessible of Cp activities, we argue that it makes sense to engage the broader spectrum of Cp function.

This article forms part of a symposium in Antiviral Research on “From the discovery of the Australia antigen to the development of new curative therapies for hepatitis B: an unfinished story.”

A standard overview of the HBV lifecycle and HBV

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a parsimonious small virus, encoding only four open reading frames. Because it is so compact it must be adapted to its host to take full advantage of host systems (sometimes mimicking host proteins, something commonly seen in viruses (Burg et al., 2015; Drayman et al., 2013; Mueller, 2015; Qin et al., 2015)). Consequently, HBV proteins must be multi-functional. The focus of this review is the HBV core protein (Cp).

At a first glance, Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) has a typical viral lifecycle (Gish et al., 2015; Seeger et al., 2007). Infection begins with endocytic entry via interaction between the surface glycoproteins and the Sodium Taurocholate Co-transporter Polypeptide. The virus core is released from the endosome to the cytoplasm and is transported to the nucleus, where it binds the nuclear pore complex (Rabe et al., 2003). Then, the relaxed circular viral DNA (rcDNA) is released into the nucleus where it is repaired by host enzymes and decorated with chromatin (Koniger et al., 2014). RNAs from the resulting episome are transcribed by host Pol2 and are exported, unspliced, from the nucleus. Subsequently, in the cytoplasm, viral Cp and viral polymerase (P) are translated from a full-length mRNA, the pre-genomic RNA (pgRNA). Surface proteins (HBsAg) are also translated from sub-genomic mRNAs. A P+pgRNA complex forms the packing signal, initiating RNA encapsidation by Cp. Within the resultant RNA-filled core, the linear pgRNA is reverse transcribed and digested leaving a relaxed circular double stranded DNA (rcDNA). The rcDNA-filled cores may be transported back to the nucleus or bind to newly synthesized endoplasmic reticulum-bound surface proteins for secretion from the cell.

HBV is an enveloped DNA virus with an icosahedral core, the so-called Dane particles. Micrographs show that most virion cores are uniform though some appear empty, some small, and others outwardly aberrant (Stannard and Hodgkiss, 1979). Of note, in one patient, the fraction of defective particles increased over time, suggesting a change in the dominant species/quasi-species and demonstrating that not all infections are the same. The presence of empty cores in Dane particles is an open question; a recent study shows that as much as 90% of secreted particles may indeed be empty (Ning et al., 2011).

The icosahedral virus core is the organizing framework of the virion (Dryden et al., 2002) and its lipid envelope is studded with surface protein, HBsAg. Although these envelopes only loosely interact with cores (Seitz et al., 2007; Stannard and Hodgkiss, 1979), the organization of surface proteins, despite averaging techniques that result in loss of much of the detail, has also been observed in helical reconstructions of subviral HBsAg particles (Short et al., 2009).

Cores, Capsids and Core protein (Cp) structures

Cp, also known as HBcAg, is usually found in four quaternary structures: a soluble dimer with ‘e’ antigenicity (HBeAg), a soluble dimer that resembles the capsid form, T=3 capsids, and T=4 capsids. The Cp gene has two start codons. Cp is translated starting with the second AUG. The first 149 residues form the α helix-rich assembly domain. The last 34 (or 36) residues form the arginine-rich C-terminal domain (CTD). Cp is always isolated as a dimer (Wingfield et al., 1995), where the dimerization is accomplished by the formation of four helix bundle, with two helices from each half-dimer (Bottcher et al., 1997; Conway et al., 1997; Wynne et al., 1999). The ends of the dimer, distal to the four helix bundle are responsible for interdimer contacts.

Cysteine 61, located in the middle of the four helix bundle, can form a disulfide crosslinking the Cp dimer. However, though C61 is conserved, the C61-C61 disulfide is not required for assembly (Nassal et al., 1992; Zhou and Standring, 1992); indeed, disulfide-bonded dimer is less assembly active than the reduced form (Schodel et al., 1993; Selzer et al., 2014a). HBeAg arises from the first AUG, which is 30 codons 5’ of the second and leads to addition of signal sequence. This signal sequence is cleaved co-translationally, leaving behind ten N-terminal acids including C(-7). This short leader sequence can form an alternative C(-7)-C61 intramolecular disulfide leading to an assembly-inactive form (Wasenauer et al., 1993; Wounderlich and Bruss, 1996).

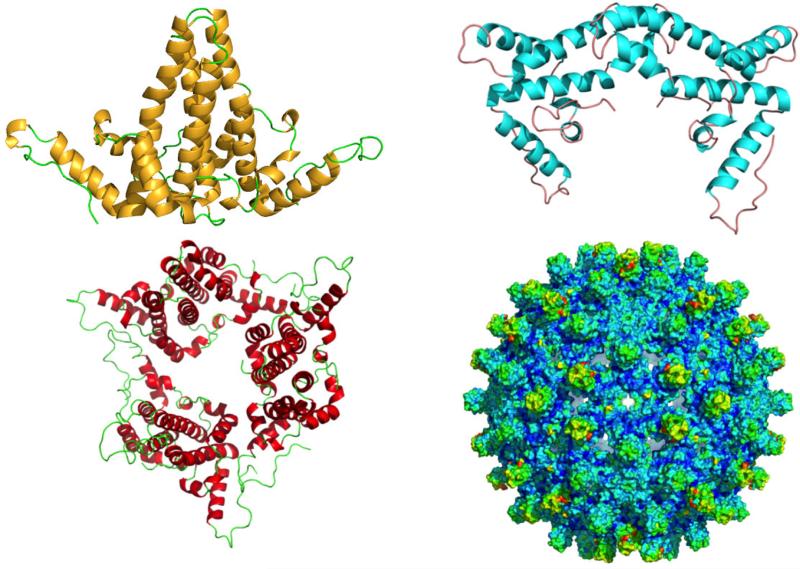

The best-documented activity of Cp is capsid formation. HBV capsids are found in two sizes: predominantly T=4 particles comprised of 120 Cp dimers with a scattering of 90-dimer T=3 particles (Figure 1). About 5% of the particles from human serum were “small” (in retrospect T=3) based on negative stain transmission Electron Microscopy (EM) (Stannard and Hodgkiss, 1979); the actual percentage of T=3 particles depends on mutations, redox state of the protein and ionic strength for in vitro assembly (Harms et al., 2015; Selzer et al., 2014b; Zlotnick et al., 1996). The first image reconstructions of E coli-expressed capsids (Crowther et al., 1994) also showed a small fraction of T=3 particles. In a T=4 icosahedral capsid there are four “quasi-equivalent environments”, A through D; by convention, AB dimers extend from fivefold to quasi-sixfold vertices and CD dimers connect quasi-sixfold vertices. Thus there are five A subunits around each fivefold and around each quasi-sixfold vertex are B-C-D-B-C-D. In a T=3 capsid, there are three quasi-equivalent sites, A through C, and the quasi-sixfold vertices have a sequence of B-C-B-C-B-C. The interdimer contacts surround vertices and are made when a loop near the assembly domain C-terminus fits into the helix-loop-extended structure at the assembly domain C-terminus of a neighboring subunit.

Figure 1. Dimer and capsid structures.

(A) A Cp dimer from an icosahedrally averaged capsid structure (PDB ID: 1QGT) is predominantly alpha helical with the dimeric interface comprising of a four helix bundle with two helices from each monomer (Wynne et al., 1999). (B) The HBeAg dimer structure (PDB ID: 3V6Z) has a drastically altered dimeric interface (Dimattia et al., 2013). (C) The structure of the assembly incompetent Y132A mutant (3KXS) is organized as a trimer of dimers with distinct tertiary structure differences from the assembly competent version (Packianathan et al., 2010). (D) The structure of a T=4 wild type capsid has the four helix bundle forming the spikes on the surface. These images are not to scale.

The crystal structures for HBeAg and an assembly-incompetent Cp mutant tell a striking story (Figure 1). In spite of the huge quaternary structure change, the monomers from HBeAg, the Y132A mutant, and Cp from capsid have very similar tertiary structures. HBeAg dimers with the C(-7)-C61 disulfide do not assemble while the reduced form does (Schodel et al., 1993; Watts et al., 2011; Watts et al., 2010). The assembly-incompetent Cp assembly domain, Cp149-Y132A, is missing the tyrosyl side chain at the tip of the loop that makes interdimer contacts. In wild type Cp, this side chain goes from nearly completely exposed in free dimer to nearly completely buried in capsid (Wynne et al., 1999); the mutant does not assemble in solution but can co-assemble with wildtype, at greatly weakened association energy (Bourne et al., 2009). The Cp149-Y132A crystal structure shows an asymmetric structure, similar to the structure of dimer in capsid (Packianathan et al., 2010). However, in Cp149-Y132A, the shoulders are lifted slightly, moving a ‘fulcrum’ helix, which in turn changes the tertiary and quaternary interactions of the intradimer four helix bundle. These connected conformational changes support an allosteric model. However, the Y132A differences are small when compared to the HBeAg structure (Dimattia et al., 2013). When the N-terminal extension forms a disulfide with C61 it causes the other half of the dimer to rotate by 140°, resulting in a radically different interface based on the same exact residues. HBeAg could not have achieved its structure if that conformation were not available to an HBcAg dimer, indicating that dimers have an extraordinary degree of flexibility.

For T=4 capsids, there are two crystal structures and one cryo-EM structure at 4Å or better resolution (Bourne et al., 2006; Wynne et al., 1999; Yu et al., 2013). These provide a consistent picture where AB and CD dimers are nearly twofold symmetric. They should not suggest that capsids are more conformationally restricted than dimers. Structures of T=4 capsid with bound drugs (HAP1 and AT130, both discussed later in this review) show that the CD dimer in particular can make dramatic structural changes to accommodate a bound small molecule (Bourne et al., 2006; Katen et al., 2013). Though HAP1 and AT130 (Figure 2) have different chemistries, they fit in the same pocket at the interdimer contact. Unlike canonical protein-protein interactions, those holding a virus capsid together are based on weak association energy and are therefore, unsurprisingly, non-complementary. HAP1 and AT130 fill a gap between two dimers, increasing the buried hydrophobic surface. In order to adjust to the bulge, the CD dimers shift their assembly domain C-terminal inter-dimer contacts, which allosterically lead to partial unfolding of the intra-dimer four helix bundles.

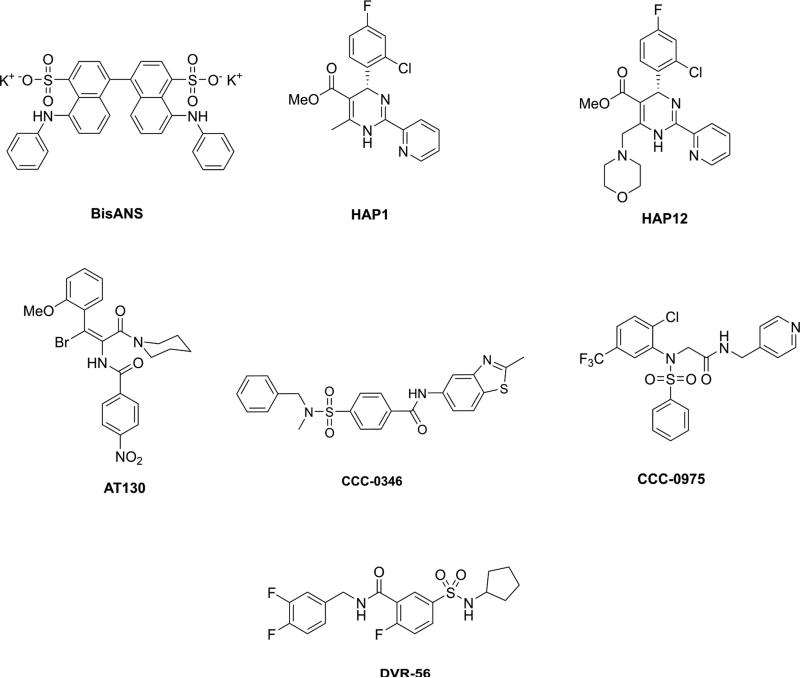

Figure 2.

A panel of non-nucleoside antivirals and selected CpAM structures.

A major role of the HBV capsid is to package nucleic acid and shuttle it to the nucleus. Cryo-EM structures have shown that RNA and the basic CTD line the capsid interior (Wang et al., 2012a; Zlotnick et al., 1997). However, CTDs, which carry a nuclear localization signal (Haryanto et al., 2012; Kann et al., 1999; Yeh et al., 1990), can be transiently exposed on the capsid exterior (as shown by accessibility to binding by a kinase) (Chen et al., 2011). As might be expected for authentic RNA-filled cores, where assembly is initiated by a specific P-pgRNA complex that is central to multiple template transfers (see below), it appears that the P protein has a specific location with respect to the capsid, but interior to the RNA layer (Wang et al., 2014).

Mass spectrometry has led to important insights into HBV structure. Because HBV capsids have been the subject of numerous assembly studies (summarized in (Zlotnick and Fane, 2011)), it is important to note that capsids from E coli and assembled in vitro under mild conditions lead to complete capsids (Pierson et al., 2014; Uetrecht et al., 2008). However, as predicted by theory, when association energy is relatively strong, incomplete capsids are readily trapped (Pierson et al., 2014). The capsids and dimers that are able to adopt so many structures are found to be extremely flexible based on protease sensitivity and the hydrogen-deuterium exchange rate (Bereszczak et al., 2013; Bereszczak et al., 2014; Hilmer et al., 2008).

Cp and cccDNA

The HBV lifecycle can be revisited from the perspective of core protein, a perspective we will follow through the rest of this review.

The root of chronic HBV infection is a genomic episome, covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). Recycling mature relaxed circular (rc) DNA-filled) cores to the nucleus replenishes cccDNA to maintain infection. However, years of treatment with nucleoside analogs, which prevent formation of new virions, only sporadically results in loss of virus (Gish et al., 2007). Thus, cccDNA is persistent throughout the cycle of infectivity. cccDNA is decorated with the usual proteins of euchromatin with the addition of two HBV proteins: X and Cp (Belloni et al., 2009; Bock et al., 2001; Buendia and Neuveut, 2015; Ducroux et al., 2014; Fallot et al., 2012; Levrero et al., 2009; Lucifora et al., 2011; Pollicino et al., 2006). The interaction of Cp with core protein is poorly understood and this information is just beginning to accumulate. Cp was identified on cccDNA isolated from stably transfected AD38 cells and found to correlate with changes in the number of nucleosomes (Bock et al., 2001). Indeed, nucleosome spacing, at least on duck HBV cccDNA appears non-random (Shi et al., 2012). Chromatin Immuno-Precipitation (ChIP) has shown that Cp is preferentially associated with CpG islands (Guo et al., 2011). The presence of Cp on CpG island 2 correlates with increased activity of cccDNA (i.e. viral load), while methylation of DNA in CpG islands 2 and 3 correlates with decreased cccDNA activity (Guo et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014). Of note, small molecules that drive Cp assembly (Bourne et al., 2008), presumably depleting the concentration of free Cp, led to depletion of cccDNA-bound Cp and decreased production of viral RNA and proteins (Belloni et al., 2013). Another mechanism believed to deplete cccDNA-bound Cp, the E3 ubiquitin ligase NIRF1, also leads to suppression of cccDNA activity (Qian et al., 2015; Qian et al., 2012). Together these data suggest, but do not provide a mechanistic connection, that HBV Cp contributes to epigenetic regulation of cccDNA, which in turn contributes to its longevity.

Cp is also implicated in the destruction of cccDNA (Lucifora et al., 2014). Interferon α (IFN-α) is established as a therapeutic agent that can clear HBV infection, presumably at the epigenetic level (Levrero et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2013), but only shows efficacy in a subset of patients (EASL clinical practice guidelines (2012)). In a study of the mechanism of action of immunomodulators (IFN-α and antibodies to the Lymphotoxin β receptor), Lucifora and colleagues found evidence indicating that the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3A was recruited to cccDNA by direct interaction with cccDNA-bound Cp. This remarkable discovery raises the question of why an HBV protein would recruit a virus-suppressive protein. Cp may also recruit NIRF1 to regulate both Cp stability and histone modification (Qian et al., 2015; Qian et al., 2012). To speculate: perhaps Cp functions to maintain a homeostatic chronic infection. These sets of results indicate that Cp has a cccDNA regulatory function.

Cp assembly

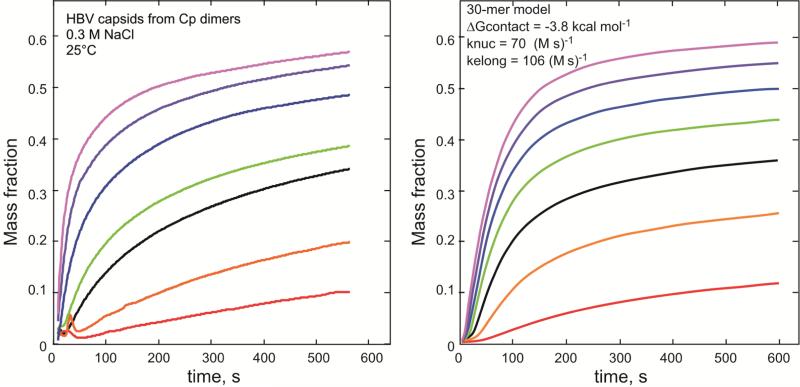

In vivo, assembly of HBV core by Cp is coordinated with specific packaging of viral pgRNA and P protein. In vitro, the truncated version of the core protein, comprising only the assembly domain, Cp149, is able to spontaneously assemble into capsids, which are morphologically indistinguishable from capsids purified from HBV expressing cells. In vitro assembly (Figure 3) occurs as a function of protein concentration, temperature and ionic strength (Ceres and Zlotnick, 2002; Wang et al., 2014; Wynne et al., 1999; Zlotnick, 2003a). The arginine-rich C-terminal domain (CTD) of Cp contributes to specific packaging of pgRNA but is dispensable for assembly of capsids (Jung et al., 2014; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a, b; Melegari et al., 2005; Nassal et al., 1990).

Figure 3. Capsid assembly kinetics and thermodynamics.

Assembly kinetics (from (Zlotnick and Mukhopadhyay, 2011)) comparing NaCl-induce assembly of Cp 149 at seven concentration 4-10μM to a computation based on a model with thirty subunits. The model subunits, like those of HBV, are tetravalent and associate weakly.

Thermodynamic stability of capsid can be described in terms of two related parameters, the pairwise association energy between two dimers (ΔGcontact) and the pseudo-critical concentration, (i.e. the concentration of free dimer at equilibrium or KD,apparent). At equilibrium, the concentrations of capsid and free dimer allow calculation of capsid association energy: ΔGcapsid=-RT ln([capsid]/[dimer]120), where R is the gas constant (1.987 cal/mol/deg) and T is the temperature in Kelvin. ΔGcapsid is the sum of all 240 pairwise contacts plus a relatively small term accounting for capsid symmetry: ΔGcontact ≈ ΔGcapsid/240 (Zlotnick, 2003b). KD,apparent is directly measurable from experiments, but is proportional to association also (-RT ln(KD,apparent) ≈ 2ΔGcontact). In practical terms, at equilibrium, for any reaction with initial [dimer] above KD,appareant, the dimer concentration remains almost constant at KD,apparent and all additional Cp assembles into capsid (Ceres and Zlotnick, 2002; Zlotnick, 2007).

From the temperature dependence of HBV capsid assembly it can be concluded that assembly is driven by entropy (Ceres and Zlotnick, 2002), consistent with burial of hydrophobic surface as shown in crystal structures (Wynne et al., 1999). Loss of hydrophobic areas at Cp inter-dimer interface creates weak hydrophobic interactions, around -3 kcal/mol, corresponding to a millimolar dissociation constant. The weak hydrophobic interactions are sufficient to form stable capsids because each dimer is tetravalent, binding four neighboring subunits (Ceres and Zlotnick, 2002; Katen and Zlotnick, 2009; Zlotnick, 2007). In part because of the barrier to breaking four bonds to release bound dimers, the intact capsid is resistant to disassembly (Singh and Zlotnick, 2003).

Kinetics of assembly are complicated because building one virion requires many components and many steps (Figure 3). In vitro capsid assembly starts with a slow nucleation step (formation of trimer of dimers), followed by a rapid elongation phase (Katen and Zlotnick, 2009; Zlotnick, 2003a; Zlotnick et al., 1999; Zlotnick and Stray, 2003). The nucleation step regulates assembly. If too many nuclei form, the growing complexes will deplete the dimer pool and the reaction will end up with trapped, incomplete intermediates (Katen and Zlotnick, 2009; Zlotnick et al., 1999). Mass spectrometry has detected the predicted large intermediates when assembly takes place under extreme conditions (Pierson et al., 2014).

Critical to interpreting any assembly data is the understanding that assembly is allosterically regulated (Zlotnick and Fane, 2011). Cp undergoes conformational change to become assembly active to participate in assembly. In vitro assembly is promoted by increasing ionic strength (Ceres and Zlotnick, 2002; Stray et al., 2004). Ionic strength changes in the range of 100 to 1000 mM may act by suppressing long-range electrostatic repulsion (Kegel and Schoot Pv, 2004) or may induce Cp conformation to an assembly-active state. In support of the latter possibility, zinc ions induce conformational change and trigger assembly at micromolar concentrations (Stray et al., 2004). Mis-regulation of assembly has also been observed with small molecules, which is the basis for the development of the allosteric modulators that will be discussed later in this review.

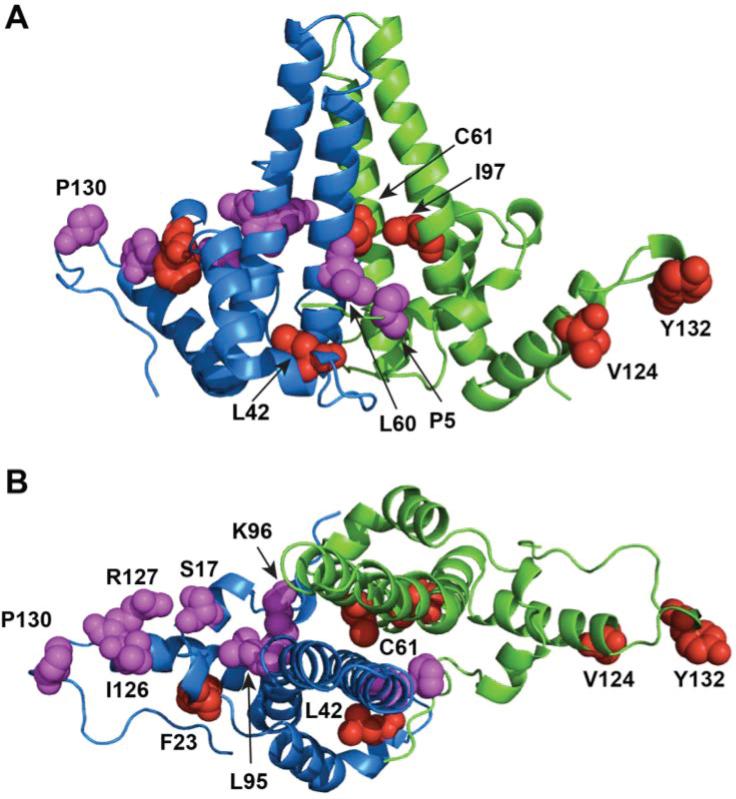

Mutants provide insight into the basis of allosteric change in Cp (Figure 4). For example, an assembly-incompetent Cp mutant was designed to take advantage of Y132, a residue on the exterior of a dimer that becomes buried during assembly and contributes about 10% of the hydrophobic surface at a dimer-dimer interface (Wynne et al., 1999). When it is replaced by alanine, the resulting protein was unable to nucleate capsid assembly but could co-assemble with wild type Cp to form morphologically normal capsids that were fragile, suggesting that the mutation weakened interfacial association energies. Similarly, the V124W mutant increases buried hydrophobic surface and the strength of association energy proportionately while V124A decreases both (Tan et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2015). However, in addition to the expected change in association energy, there is an unexpected change in the hydrodynamic radius of dimer, observed by size exclusion chromatography, which indicates that Y132A and V124A are less compact than wt and V124W is more compact. That is, these side chains, presumably on the exterior of the Cp dimer affect the protein's structure – an indication of allosteric change.

Figure 4. An HBV Cp149 dimer.

The two halves of the dimer (from PDB:1QGT) are in green and blue. Residues that affect capsid assembly are colored red. Those that affect secretion are colored magenta. (A) Cp149 dimer side view. (B) Cp149 dimer top view.

Similar behavior is seen in mutations distant from the inter-dimer interface, i.e. at the intra-dimer interface (Figure 4). These mutations affect assembly kinetics and thermodynamics, indicating that changes in Cp dimer conformation can up- or down-regulate assembly. An intradimer disulfide bond, between dimer-related cysteine 61 residues at the center of the four helix bundle, is reported to cause slow assembly kinetics and decreased capsid stability (Selzer et al., 2014a). Conversely, a naturally occurring mutation F/I 97L (F97 in subtype ayw, I97 in subtype adr), located near C61, enhances assembly rate and extent in vitro (Ceres et al., 2004) while in vivo leads to secretion of immature ssDNA-containing virions (Chua et al., 2003; Le Pogam and Shih, 2002). Assembly of F97L shows a substantially more positive enthalpy of assembly though the interdimer contact is unchanged, suggesting the mutation changes Cp dimer conformation or dynamical range of conformations (Ceres et al., 2004). Two other mutations distant from the inter-dimer interface, F23A and L42A, stabilize dimers and inhibit capsid formation, presumably by affecting the dynamic conformation of Cp (Alexander et al., 2013).

The effects of errors in assembly are pleiotropic. Timing is critical for in vivo core assembly, which involves packaging of pgRNA and P complex. Errors in assembly can disconnect capsid formation from pgRNA packaging and lead to empty particles. Cp variants, V124W and V124A, which have very fast and slow kinetics, respectively, both package less pgRNA (Tan et al., 2015). Interestingly, Ning et al have reported that a majority of virions secreted in transient transfection system and patient sera are empty, devoid of nucleic acid (Ning et al., 2011). They also observed lack of nucleic acid in the majority of intracellular capsids. Considering the strong electrostatic interactions between CTD and nucleic acid, the prevalence of empty cores is surprising (Hagan, 2009; Newman et al., 2009; Perlmutter et al., 2014).

Naturally occurring HBV Cp mutations affect assembly as well as the life cycle downstream of encapsidation, especially virion secretion (Figure 4). For example, F/I 97L is found to cause secretion of immature particles - virions containing single strand DNA (Yuan et al., 1999). This immature section can be rescued by a correlated P130T mutation (Yuan and Shih, 2000). Like P130T, P5T and L60V mutations inhibits virion secretion (Le Pogam et al., 2000). It is likely that these mutations modify capsid structure and disrupt the connection of capsids and surface proteins during envelopment and secretion. In fact, mutagenesis analysis of the capsid surface has shown that mutations of residues at the base of the central α-helix bundle, such as S17, L60, L95, K96, and I126, and R127 support intracellular capsid formation while abolish virion secretion (Pairan and Bruss, 2009; Ponsel and Bruss, 2003).

Regulation of assembly may have a role in packaging specificity. Outside the context of an HBV expression system, the full-length protein aggressively assembles on any RNA, for example, in an E coli expression system it packages random bacterial RNA (Nassal, 1992) where the amount of RNA is proportional to the charge of the C-terminus (Newman et al., 2009; Porterfield et al., 2010; Porterfield and Zlotnick, 2010; Yu et al., 2013). Indeed the full-length Cp will bind cooperatively to random dsDNA in vitro but is unable to package it (Dhason et al., 2012). Remarkably, in an HBV expression system, Cp either assembles to empty capsids or specifically packages RNA containing the P-binding epsilon loop (Bartenschlager and Schaller, 1992; Ning et al., 2011). In light of the above data, it has been speculated that a cellular protein acts as a chaperone to prevent inappropriate assembly (Chen et al., 2011).

Comparisons between HBV and Woodchuck HBV (WHV) have been deeply illuminating (Menne and Cote, 2007). Unlike humans, woodchucks hibernate with body temperature fluctuating between 4°C and 37°C. Though HBV and WHV share 65% sequence identity, WHV Cp has faster assembly kinetics, stronger association energy than HBV Cp, and produces a large fraction of defective particles. Interestingly, where HBV Cp assembly has a steep temperature dependence, WHV association energy is relatively strong at both 37° and 4°C, which suggests the virus has adapted to hibernating host and a tendency to kinetic traps (Kukreja et al., 2014).

Cp and reverse transcription

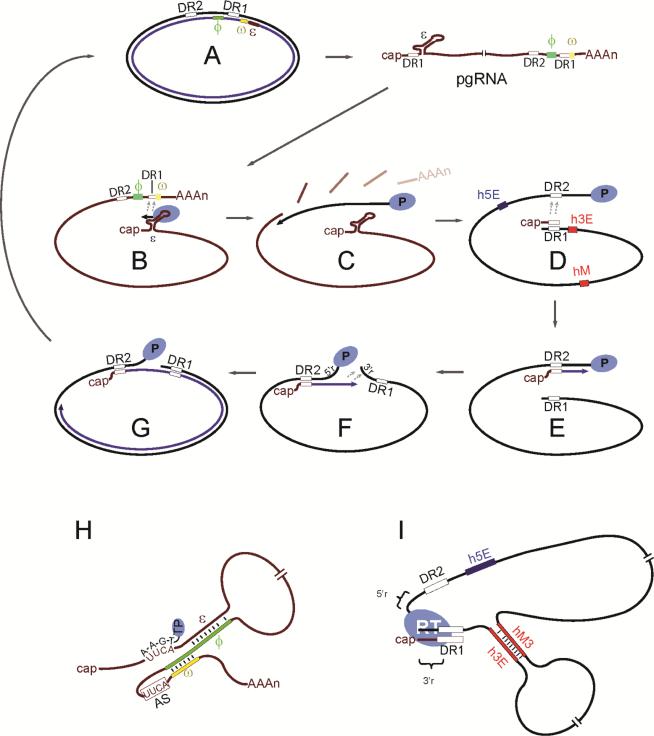

Hepadnaviral reverse transcription is a multi-step process involving genome rearrangements and template switches (Figure 5). Reverse transcription requires the activity of the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of Cp at multiple stages. Recent data indicates the capsid itself plays an important role.

Figure 5. Reverse transcription is a multi-step process.

(A,B) First, the pregenomic RNA (pgRNA) is encapsidated (encapsidation) when the stem loop structure epsilon (ε) binds the P protein to form the encapsidation signal (Bartenschlager et al., 1990; Bartenschlager and Schaller, 1992; Chiang et al., 1992; Nassal et al., 1990; Pollack and Ganem, 1993). Minusstrand DNA is then primed from tyrosine 63 of the P protein (Gerlich and Robinson, 1980; Nassal and Rieger, 1996; Rieger and Nassal, 1996; Tavis et al., 1994; Wang and Seeger, 1992; Zoulim and Seeger, 1994). (B) The nascent 3- or 4-mer DNA then switches template to a complementary sequence near the 3’ end of the pgRNA (minus-strand template switch) ((Nassal and Schaller, 1996; Rieger and Nassal, 1996; Tavis et al., 1994; Wang and Seeger, 1993)) in a process that is targeted by base pairing between cis-acting sequences ϕ and ω that flank the acceptor site (panel H) (Abraham and Loeb, 2006, 2007). (C) Minus-strand DNA is then elongated on the pgRNA template (minus-strand DNA elongation). RNase H activity of the P protein digests the pgRNA but leaves the 5’-most ~17 nucleotides undigested (Chen and Marion, 1996; Haines and Loeb, 2007; Radziwill et al., 1990; Will et al., 1987). (D, E) The 5’ RNA fragment switches from its location annealed to the 11-nucleotide Direct Repeat 1 (DR1) to the Direct Repeat 2 (DR2) sequence near the 5’ end of the minus-strand DNA (primer translocation). This template switch requires cis-acting sequences h3E, hM and h5E (panel I) (Lewellyn and Loeb, 2007; Seeger et al., 2007; Will et al., 1987). (F) A final template switch between the 5’ and 3’ terminal redundancies (5’r and 3’r) circularizes the DNA molecule (circularization) (Will et al., 1987). (G) Plus-strand DNA synthesis then resumes (plus-strand DNA elongation) to produce a mature, relaxed-circular DNA genome.

Capsids assembled from Cp lacking the CTD do not encapsidate pgRNA (Gallina et al., 1989; Nassal, 1992), but many CTD mutants that do encapsidate pgRNA still prevent the synthesis of rcDNA (Chua et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2014; Kock et al., 2004; Lan et al., 1999; Le Pogam et al., 2005; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a, b). Residues 150-173 of the CTD appear to be sufficient for rcDNA synthesis, thus many studies have focused on these residues (Le Pogam et al., 2005). Four clusters of three or four arginines within this region appear to be particularly important because replacing any of the clusters with alanines or glycines results in little to no detectable rcDNA synthesis (Chua et al., 2010; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011b). However, replacing one or more clusters with lysines also greatly reduces rcDNA synthesis so the CTD likely provides more than just positive charge (Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a). Mechanistic analyses of these mutations reveal that the decreases in rcDNA synthesis are the result of reduced pgRNA encapsidation, preferential encapsidation of spliced RNAs (Le Pogam et al., 2005; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a), and disruption of all steps of reverse transcription including template switch and DNA elongation steps (Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a). This result is striking because the minus-strand template switch, plus-strand template switch, and minus- and plus-strand DNA elongation steps are mechanistically distinct (Figure 5). Together these results suggest that the CTD makes pleiotropic contributions to reverse transcription.

Synthesis of rcDNA also requires CTD phosphorylation. Serines 155, 162, and 170 are known phosphoacceptor sites (Gazina et al., 2000; Lan et al., 1999; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011b; Liao and Ou, 1995; Melegari et al., 2005; Yeh and Ou, 1991). Jung et al. have recently identified additional phosphoacceptor sites T162, S170, and S178 in genotype adw (corresponding to T160, S168, and S176 in ayw) (Jung et al., 2014). Like mutations in the arginine clusters, mutations in the phosphoacceptor sites cause preferential encapsidation of spliced pgRNA (Kock et al., 2004). Furthermore, alanine substitutions at any of the confirmed phosphoacceptor sites cause defects at all steps of DNA synthesis, as was observed for mutations at the arginine clusters (Jung et al., 2014; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011b). In contrast, glutamate or aspartate substitutions at the phosphoacceptor sites, which mimic phosphorylated serine, supported DNA synthesis (Gazina et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2014; Kock et al., 2004; Lan et al., 1999; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011b). These findings suggest that phosphorylated CTD is the active form of the CTD for all steps of reverse transcription, including the synthesis of plus-strand DNA. Interestingly, the CTD is dephosphorylated in mature avihepadnaviruses (Perlman et al., 2005).

Several hypotheses have been proposed for how the CTD may contribute to reverse transcription. Le Pogam et al. (Le Pogam et al., 2005) proposed that the positive charges of the CTD “balance” negative charges on encapsidated nucleic acids. This model predicts that the steps that would be most affected by CTD mutations would be pgRNA encapsidation and plus-strand DNA synthesis because these steps increase the encapsidated negative charge. However, CTD mutations have been shown to affect steps that do not increase the encapsidated negative charge such as template switch steps and minus-strand DNA elongation (with accompanying RNA digestion) (Jung et al., 2014; Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a, b). Therefore, this model does not fully account for the contribution of the CTD during reverse transcription. An alternative model proposed by Lewellyn and Loeb (Lewellyn and Loeb, 2011a) suggests that the CTD may function as a nucleic acid chaperone. Nucleic acid chaperones catalyze the breaking and reforming of base pair interactions (Rajkowitsch et al., 2007). In retroviruses and retrotransposons, this activity is provided by the nucleocapsid protein (NC) and is required to catalyze both template switching and DNA elongation (Cristofari et al., 2000; Levin et al., 2005; Levin et al., 2010; Martin and Bushman, 2001; Williams et al., 2002). To test this hypothesis, Chu et al (Chu et al., 2014) tested the ability of the CTD to catalyze nucleic acid strand exchange and hammerhead ribozyme activity in vitro and found that the CTD is a potent nucleic acid chaperone. Nucleic acid chaperone activity provides a compelling explanation for how one 34 residue domain can orchestrate the myriad template switches and genome rearrangements that occur during reverse transcription.

The assembly domain also contributes to reverse transcription; the capsid is not an inert container. Mutations to the Cp assembly domain, which affect assembly, support minus strand DNA synthesis but specifically abrogate all evidence of second strand synthesis (Tan et al., 2015). Similarly, the capsid is responsive to nucleic acid contents. rcDNA-filled cores are less stable than ssDNA-filled and ssRNA-filled cores based on sensitivity to nucleases and proteases as well as biophysical properties such as migration through a gel (Cui et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2010). Slight structural differences have been observed in dsDNA-filled capsids compared to RNA-filled capsids (Roseman et al., 2005). The process of reverse transcription may itself destabilize the capsid. Based on calculations, the amount of stress imposed on the HBV capsid by packaged dsDNA increases precipitously as the DNA approaches full-length (Dhason et al., 2012).

The Cp CTD and host partners

Cp interacts with host proteins (Nguyen et al., 2008). A critical gap in the field is that only a few of these interactions have been described. The best understood feature is the CTD. CTD, normally located inside the core particle displays a nuclear localization signal (NLS) on the exterior (Kann et al., 1999; Ludgate et al., 2011). The NLS is localized to the arginine-repeats (Liao and Ou, 1995; Yeh et al., 1990). As with many NLS sequences its activity is modulated by phosphorylation (Nardozzi et al., 2010), but probably not in the usual way. A likely explanation is that phosphorylation weakens interaction of the CTDs with encapsidated nucleic acid (Kann et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2015; Rabe et al., 2003). The CTDs bind importin α/β complexes or perhaps only importin β, which act as adapters for transport of cores to the nuclear pores (Kann et al., 2007). In the nuclear pore itself, cores interact with the Nup153 and apparently dissociate during entry to the nucleus (Rabe et al., 2009; Rabe et al., 2003; Schmitz et al., 2010). NLS phosphorylation may be required for interaction with the nuclear pore complex (Haryanto et al., 2012). Of note, the destabilization of the core may occur before it reaches the nuclear pore as a function of core maturation presumably due to completion of rcDNA and change in CTD phosphorylation state (Basagoudanavar et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2013; Haryanto et al., 2012; Perlman et al., 2005). Indeed, cleavage of DNA-bound P protein appears to begin while core is in the cytoplasm (Guo et al., 2010).

The identities of the kinases, there are likely more than one that actually phosphorylate the CTD, are open to question. Exhaustive analysis of immuno-reactivity and inhibitors suggest that CDK2 is packaged in cores (Ludgate et al., 2012). However, PKC and others have also been implicated (Kann et al., 1993). SRPK1 and SRPK2, normally associated with phosphorylation of spliceosomal proteins (Zhong et al., 2009) but also involved with retrovirus RNA synthesis (Fukuhara et al., 2006), immunoprecipitates with the CTDs, modulates viral replication, and binds Cp and cores with a nanomolar dissociation constant (Chen et al., 2011; Daub et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2005). Indeed, the Cp CTD closely resembles the SR proteins (Ricco and Kanduc, 2010) that are SRPKs intended substrates. We suggest that different kinases play different roles in the viral lifecycle and may do so redundantly.

Cp-directed antivirals

HBV appears to follow an ordered assembly pathway where interactions between subunits are well defined. Deviations of assembly path or intersubunit geometry can lead to defective or aberrant particles that are not infectious. Inactive particles also sequester subunits that would otherwise be used for productive assembly leveraging the activity of a small number of antiviral agents. Furthermore, Cp has activities outside of assembling an inert capsid and a small molecule can differentially interfere with each one of these activities by favoring or disfavoring specific Cp conformations. Because the underlying mechanism of these activities is not based on Michaelis-Menten models of inhibition or even directly blocking an activity, it is misleading to describe Cp-directed molecules as inhibitors. Because their mechanism of action is based on allostery, our preferred terminology is Cp Allosteric Modulators or CpAMs (Figure 2).

Theoretical descriptions of CpAMs were originally laid out based on a focus on assembly (Prevelige, 1998; Zlotnick et al., 2002; Zlotnick and Stray, 2003). A CpAM can misdirect assembly in two ways: it could (i) alter the subunit structure to stabilize an assembly-incompetent state or (ii) alter inter-subunit interactions. Either of these changes will affect the assembled product formed. Conceptually, an antiviral agent could block contacts by obstructing contact surfaces. It could strengthen interactions. It could misdirect assembly by altering the geometry of intersubunit contacts. In each case, these interactions may be due to direct interaction with an intersubunit contact surface or indirectly by allostery. Many of these effects have been demonstrated in Cp mutants.

Misdirection of HBV capsid assembly by a small molecule was first identified in in vitro assembly studies with a fluorescent dye 5,5’-bis[8-(phenylamino)-1-naphthalenesulfonate] (BisANS, Figure 2) (Zlotnick et al., 2002). BisANS was previously shown to bind bacteriophage P22 coat and scaffolding proteins to prevent assembly (Teschke et al., 1993). With HBV, BisANS-bound Cp dimer had a decreased propensity to assemble and an increased propensity for formation of non-capsid polymers.

Heteroaryldihydropyrimidines (HAPs) were found to affect virus production in a core dependent manner in vitro (Deres and Rubsamen-Waigmann, 1999; Deres et al., 2003) and in vivo (Weber et al., 2002). In vitro studies on the effect of HAP (HAP1, Figure 2) presence on capsid assembly revealed that they misdirected capsid assembly to form aberrant non-capsid polymers (Stray et al., 2005; Stray and Zlotnick, 2006). Unlike BisANS, HAPs also enhanced the rate of capsid assembly over a broad concentration range (Bourne et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012b). HAPs allosterically induced assembly-active states at stoichiometric levels and stabilized non-capsid polymers at higher concentrations.

Structural studies of HAPs with the HBV capsid protein revealed a variety of aberrant complexes (Hacker et al., 2003; Stray et al., 2005). Electron microscopy showed that the noncapsid polymers were comprised of hexagonal arrays of the capsid protein (Stray et al., 2005) suggesting that a hexameric unit may be a preferred quaternary structure of the HAPs. In general, sub-stoichiometric concentrations of HAPs, up to one active HAP per two Cp dimers, accelerate assembly in a dose-dependent manner and yield spherical capsids. At higher ratios, active HAP leads to non-capsid polymer exclusively (Stray and Zlotnick, 2006). Different HAPs lead to different aberrant structures, reflecting their effects on the kinetics and geometry of assembly (Bourne et al., 2008). HAPs show virus suppressive activity at concentrations far lower than those required for aberrant assembly, suggesting HAP kinetic effects are far more important to interfering with virus assembly important than aberrant quaternary structure (Li et al., 2013). Of note, at very high concentrations, HAPs can suppress rebound of HBV production after cessation of treatment (Wu et al., 2013) and alter the epigenetic markers associated with cccDNA including acetylated histone H3 (Belloni et al., 2013).

A second class of non-nucleoside compounds – phenylpropenamides (PPAs, AT130, Figure 2) were also found to inhibit HBV infectivity in cell culture (Delaney et al., 2002; King et al., 1998; Perni et al., 2000). In vitro capsid assembly studies showed that the PPAs accelerated but did not misdirect assembly (Katen et al., 2010). Capsids formed in presence of PPAs appeared to be morphologically normal. However, in cell culture, PPAs led to accumulation of empty capsids (Feld et al., 2007). The in vitro results suggest that PPA-driven assembly, at an inappropriate time and place, is the basis for preventing RNA packaging.

Crystal structures of these CpAMs in complex with assembled capsids revealed that binding of these molecules is associated with large-scale allosteric conformational changes in the subunits. The crystal structure of the HBV capsid in complex with HAP1 (Figure 2) showed that quaternary structure changes occur in the capsid, with the subunits of the asymmetric unit moving as connected rigid bodies, but with little variation in the tertiary structure (Bourne et al., 2006). The crystal structure of an HBV capsid bound to a phenylpropenamide – AT130, however, revealed that there were both tertiary and quaternary structure changes associated induced in the capsid with binding (Katen et al., 2013). The structural changes were large enough to make the complexed capsids crystallize with alternate unit cell parameters.

HAPs and PPAs bind a hydrophobic pocket at the dimer-dimer interface near the C-termini of the core protein subunits, with contributions from two neighboring dimers. The pocket is not observable from the capsid exterior and is only partially exposed on the capsid interior. It comprises a concave depression from one subunit accommodating the ligand and a helical segment from an adjacent subunit that caps the pocket. Filling the HAP pocket induces local and global tertiary and quaternary structure changes to accommodate the CpAM, suggesting an induced fit mechanism. Only the B and C subunits of T=4 HBV capsids have bound CpAM, the A and D subunits do not have appropriate quaternary structure (Bourne et al., 2006; Katen et al., 2013). Each of the CpAMs studied thus far has a different affinity for each pocket despite their quasi-equivalence. A V124W mutation fills the HAP pocket and blocks activity of HAPs and PPAs (Katen et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2015).

New classes of CpAMs, with diversified architectures, are emerging. Sulfanilamides are representative of the classes of compounds on the horizon. Promising leads from this series include CCC-0346 (EC50 = 0.35 μM) and CCC-0975 (EC50 = 4.55 μM, Figure 2) that are believed to target the conversion of rcDNA to cccDNA (Cai et al., 2012). Suppressing cccDNA formation represents a new strategy for combating chronic HBV infection and should be of great interest to the drug discovery community. However the actual mechanism of action is not clear. A related class of compounds, the sulfamoylbenzamides, as exemplified by the compound DVR-56 (EC50 = 0.39 μM, Figure 2), was found to interfere with pgRNA-packaging, reminiscent of the PPAs. Intriguingly, both the sulfanilamides and the sulfamoylbenzamides have been shown to disrupt normal capsid formation (Campagna et al., 2013; Cho et al., 2013). Cho et al. used hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry to confirm that several sulfanilamide derivatives bind to the HBV core protein. Of note, it could not be established that Cp-binding event ultimately led to the other activities (Cho et al., 2013).

CpAMs in general, and HAPs specifically, have a broad range of effects differentially seen at low and high concentrations. By activating and accelerating assembly at inappropriate conditions they prevent formation of new, active cores. Considering the V124 mutants (Tan et al., 2015), CpAMs are likely to have synergistic effects on reverse transcription. Moreover, by favoring capsid assembly, CpAMs deplete the concentration of free Cp that might otherwise participate in other activities.

A future for core-protein directed antivirals

The core protein of HBV has been shown to bind a variety of small molecules, collectively known as CpAMs. These CpAMs have different phenotypic effects: misdirected assembly, fast assembly, failure of capsids to package RNA, and interference with establishment of new cccDNA. In fact, these activities may be different faces of allosteric activation of Cp. The core protein is pleiotropic and thus allosteric effectors are also expected to be pleiotropic.

Perhaps the most interesting activity is that high concentrations of an assembly-directed CpAM, HAP12, also modified cccDNA epigenetics. This is a wholly different activity of Cp and a CpAM. This result suggests that HAPs bind Cp weakly to allosterically affect cccDNA; this is in addition to the now well accepted effect of enhancing assembly. Such allosteric modulators, acting on Cp upstream of assembly have untapped potential to destabilize cccDNA activity and chronic infection.

Highlights.

HBV core protein (Cp) is a small, helical homodimer that has many functions vital to the viral lifecycle

In the nucleus, Cp can affect the epigenetics of viral DNA

In the cytoplasm, Cp assembles into 120-dimer capsids that are the sites of DNA synthesis

Cp is allosteric and thus susceptible to control by core protein allosteric modulators (CpAMs)

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Uri Lopatin and Dr. Lisa Selzer for their helpful comments. AZ and BV were supported by NIH grants R56-AI077688 and R01-AI067417. The Zlotnick lab has also received support from Assembly Biosciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham TM, Loeb DD. Base pairing between the 5′ half of epsilon and a cis-acting sequence, phi, makes a contribution to the synthesis of minus-strand DNA for human hepatitis B virus. Journal of virology. 2006;80:4380–4387. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4380-4387.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham TM, Loeb DD. The Topology of Hepatitis B Virus Pregenomic RNA Promotes Its Replication. Journal of virology. 2007;81:11577–11584. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01414-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CG, Jurgens MC, Shepherd DA, Freund SM, Ashcroft AE, Ferguson N. Thermodynamic origins of protein folding, allostery, and capsid formation in the human hepatitis B virus core protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2782–2791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308846110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartenschlager R, Junker-Niepmann M, Schaller H. The P gene product of hepatitis B virus is required as a structural component for genomic RNA encapsidation. J.Virol. 1990;64:5324–5332. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5324-5332.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. Hepadnaviral assembly is initiated by polymerase binding to the encapsidation signal in the viral RNA genome. EMBO J. 1992;11:3413–3420. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basagoudanavar SH, Perlman DH, Hu J. Regulation of hepadnavirus reverse transcription by dynamic nucleocapsid phosphorylation. Journal of virology. 2007;81:1641–1649. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01671-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni L, Li L, Palumbo GA, Chirapu SR, Calvo L, Finn MG, Lopatin U, Zlotnick A, Levrero M. HAPs hepatitis B virus (HBV) capsid inhibitors block core protein interaction with the viral minichromosome and host cell genes and affect cccDNA transcription and stability. Hepatology. 2013;58:277A. [Google Scholar]

- Belloni L, Pollicino T, De Nicola F, Guerrieri F, Raffa G, Fanciulli M, Raimondo G, Levrero M. Nuclear HBx binds the HBV minichromosome and modifies the epigenetic regulation of cccDNA function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19975–19979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908365106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereszczak JZ, Rose RJ, van Duijn E, Watts NR, Wingfield PT, Steven AC, Heck AJ. Epitope-distal effects accompany the binding of two distinct antibodies to hepatitis B virus capsids. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6504–6512. doi: 10.1021/ja402023x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereszczak JZ, Watts NR, Wingfield PT, Steven AC, Heck AJ. Assessment of differences in the conformational flexibility of hepatitis B virus core-antigen and e-antigen by hydrogen deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pro.2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock CT, Schwinn S, Locarnini S, Fyfe J, Manns MP, Trautwein C, Zentgraf H. Structural organization of the hepatitis B virus minichromosome. Journal of molecular biology. 2001;307:183–196. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottcher B, Wynne SA, Crowther RA. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 1997;386:88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne C, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. Global structural changes in hepatitis B capsids induced by the assembly effector HAP1. Journal of virology. 2006;80:11055–11061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00933-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne C, Lee S, Venkataiah B, Lee A, Korba B, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. Small-Molecule Effectors of Hepatitis B Virus Capsid Assembly Give Insight into Virus Life Cycle. Journal of virology. 2008;82:10262–10270. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01360-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne CR, Katen SP, Fulz MR, Packianathan C, Zlotnick A. A Mutant Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein Mimics Inhibitors of Icosahedral Capsid Self-Assembly. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1736–1742. doi: 10.1021/bi801814y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buendia MA, Neuveut C. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a021444. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg JS, Ingram JR, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Jude KM, Dukkipati A, Feinberg EN, Angelini A, Waghray D, Dror RO, Ploegh HL, Garcia KC. Structural biology. Structural basis for chemokine recognition and activation of a viral G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2015;347:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Mills C, Yu W, Yan R, Aldrich CE, Saputelli JR, Mason WS, Xu X, Guo JT, Block TM, Cuconati A, Guo H. Identification of disubstituted sulfonamide compounds as specific inhibitors of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4277–4288. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagna MR, Liu F, Mao R, Mills C, Cai D, Guo F, Zhao X, Ye H, Cuconati A, Guo H, Chang J, Xu X, Block TM, Guo JT. Sulfamoylbenzamide derivatives inhibit the assembly of hepatitis B virus nucleocapsids. Journal of virology. 2013;87:6931–6942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00582-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceres P, Stray SJ, Zlotnick A. Hepatitis B Virus Capsid Assembly is Enhanced by Naturally Occurring Mutation F97L. J. Virol. 2004;78:9538–9543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9538-9543.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceres P, Zlotnick A. Weak protein-protein interactions are sufficient to drive assembly of hepatitis B virus capsids. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11525–11531. doi: 10.1021/bi0261645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Wang JC-Y, Zlotnick A. A kinase chaperones hepatitis B virus capsid assembly and captures capsid dynamics in vitro. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002388. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Marion PL. Amino acids essential for RNase H activity of hepadnaviruses are also required for efficient elongation of minus-strand viral DNA. J. Virol. 1996;70:6151–6156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6151-6156.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang PW, Jeng KS, Hu CP, Chang CM. Characterization of a cis element required for packaging and replication of the human hepatitis B virus. Virology. 1992;186:701–711. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90037-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Song JS, Kim HJ, Park SG, Jung G. Structure-based design and biochemical evaluation of sulfanilamide derivatives as hepatitis B virus capsid assembly inhibitors. Journal of enzyme inhibition and medicinal chemistry. 2013;28:916–925. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.694879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu TH, Liou AT, Su PY, Wu HN, Shih C. Nucleic acid chaperone activity associated with the arginine-rich domain of human hepatitis B virus core protein. Journal of virology. 2014;88:2530–2543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03235-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua PK, Tang FM, Huang JY, Suen CS, Shih C. Testing the balanced electrostatic interaction hypothesis of hepatitis B virus DNA synthesis by using an in vivo charge rebalance approach. Journal of virology. 2010;84:2340–2351. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01666-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua PK, Wen YM, Shih C. Coexistence of two distinct secretion mutations (P5T and I97L) in hepatitis B virus core produces a wild-type pattern of secretion. Journal of virology. 2003;77:7673–7676. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7673-7676.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway JF, Cheng N, Zlotnick A, Wingfield PT, Stahl SJ, Steven AC. Visualization of a 4-helix bundle in the hepatitis B virus capsid by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 1997;386:91–94. doi: 10.1038/386091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari G, Ficheux D, Darlix JL. The GAG-like protein of the yeast Ty1 retrotransposon contains a nucleic acid chaperone domain analogous to retroviral nucleocapsid proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19210–19217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther RA, Kiselev NA, Bottcher B, Berriman JA, Borisova GP, Ose V, Pumpens P. Three-dimensional structure of hepatitis B virus core particles determined by electron cryomicroscopy. Cell. 1994;77:943–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Ludgate L, Ning X, Hu J. Maturation-associated destabilization of hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid. Journal of virology. 2013;87:11494–11503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01912-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub H, Blencke S, Habenberger P, Kurtenbach A, Dennenmoser J, Wissing J, Ullrich A, Cotten M. Identification of SRPK1 and SRPK2 as the major cellular protein kinases phosphorylating hepatitis B virus core protein. Journal of virology. 2002;76:8124–8137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8124-8137.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney W.E.t., Edwards R, Colledge D, Shaw T, Furman P, Painter G, Locarnini S. Phenylpropenamide derivatives AT-61 and AT-130 inhibit replication of wild-type and lamivudine-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3057–3060. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3057-3060.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deres K, Rubsamen-Waigmann H. Development of resistance and perspectives for future therapies against hepatitis B infections: lessons to be learned from HIV. Infection 27 Suppl. 1999;2:S45–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02561672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deres K, Schroder CH, Paessens A, Goldmann S, Hacker HJ, Weber O, Kramer T, Niewohner U, Pleiss U, Stoltefuss J, Graef E, Koletzki D, Masantschek RN, Reimann A, Jaeger R, Gross R, Beckermann B, Schlemmer KH, Haebich D, Rubsamen-Waigmann H. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by drug-induced depletion of nucleocapsids. Science. 2003;299:893–896. doi: 10.1126/science.1077215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhason MS, Wang JC, Hagan MF, Zlotnick A. Differential assembly of Hepatitis B Virus core protein on single-and double-stranded nucleic acid suggest the dsDNA-filled core is spring-loaded. Virology. 2012;430:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimattia MA, Watts NR, Stahl SJ, Grimes JM, Steven AC, Stuart DI, Wingfield PT. Antigenic Switching of Hepatitis B Virus by Alternative Dimerization of the Capsid Protein. Structure. 2013;21:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayman N, Glick Y, Ben-nun-shaul O, Zer H, Zlotnick A, Gerber D, Schueler-Furman O, Oppenheim A. Pathogens use structural mimicry of native host ligands as a mechanism for host receptor engagement. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden K, Wieland S, Chisari F, Yeager M. Structure of Native Hepatitis B Virus Particles by Electron Cryomicroscopy and Image Reconstruction. American Society for Virology 21st Annual Meeting; Lexington, Ke. 2002. pp. P20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ducroux A, Benhenda S, Riviere L, Semmes OJ, Benkirane M, Neuveut C. The Tudor domain protein Spindlin1 is involved in intrinsic antiviral defense against incoming hepatitis B Virus and herpes simplex virus type 1. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004343. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallot G, Neuveut C, Buendia MA. Diverse roles of hepatitis B virus in liver cancer. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld JJ, Colledge D, Sozzi V, Edwards R, Littlejohn M, Locarnini SA. The phenylpropenamide derivative AT-130 blocks HBV replication at the level of viral RNA packaging. Antiviral research. 2007;76:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara T, Hosoya T, Shimizu S, Sumi K, Oshiro T, Yoshinaka Y, Suzuki M, Yamamoto N, Herzenberg LA, Hagiwara M. Utilization of host SR protein kinases and RNA-splicing machinery during viral replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11329–11333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604616103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallina A, Bonelli F, Zentilin L, Rindi G, Muttini M, Milanesi G. A recombinant hepatitis B core antigen polypeptide with the protamine-like domain deleted self-assembles into capsid particles but fails to bind nucleic acids. Journal of virology. 1989;63:4645–4652. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4645-4652.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazina EV, Fielding JE, Lin B, Anderson DA. Core protein phosphorylation modulates pregenomic RNA encapsidation to different extents in human and duck hepatitis B viruses. Journal of virology. 2000;74:4721–4728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4721-4728.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich WH, Robinson WS. Hepatitis B virus contains protein attached to the 5' terminus of its complete DNA strand. Cell. 1980;21:801–809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gish R, Given BD, Lai C-L, Locarnini S, Lau JYN, Lewis DL, Schluep T. Chronic hepatitis B: natural history, virology, current management and a glimpse at future opportunities. Antiviral research. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gish RG, Lok AS, Chang TT, de Man RA, Gadano A, Sollano J, Han KH, Chao YC, Lee SD, Harris M, Yang J, Colonno R, Brett-Smith H. Entecavir therapy for up to 96 weeks in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Mao R, Block TM, Guo JT. Production and function of the cytoplasmic deproteinized relaxed circular DNA of hepadnaviruses. Journal of virology. 2010;84:387–396. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01921-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo YH, Li YN, Zhao JR, Zhang J, Yan Z. HBc binds to the CpG islands of HBV cccDNA and promotes an epigenetic permissive state. Epigenetics. 2011;6:720–726. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.6.15815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker HJ, Deres K, Mildenberger M, Schroder CH. Antivirals interacting with hepatitis B virus core protein and core mutations may misdirect capsid assembly in a similar fashion. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:2273–2279. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MF. A theory for viral capsid assembly around electrostatic cores. The Journal of chemical physics. 2009;130:114902. doi: 10.1063/1.3086041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines KM, Loeb DD. The sequence of the RNA primer and the DNA template influence the initiation of plus-strand DNA synthesis in hepatitis B virus. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;370:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms ZD, Haywood DG, Kneller AR, Selzer L, Zlotnick A, Jacobson SC. Single-particle electrophoresis in nanochannels. Anal Chem. 2015;87:699–705. doi: 10.1021/ac503527d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haryanto A, Schmitz A, Rabe B, Gassert E, Vlachou A, Kann M. Analysis of the nuclear localization signal of the hepatitis B virus capsid. International Research Journal of Biochemistry and Bioinformatics. 2012;2:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hilmer JK, Zlotnick A, Bothner B. Conformational Equilibria and Rates of Localized Motion within Hepatitis B Virus Capsids. Journal of molecular biology. 2008;375:581–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Hwang SG, Chwae YJ, Park S, Shin HJ, Kim K. Phosphoacceptors threonine 162 and serines 170 and 178 within the carboxyl-terminal RRRS/T motif of the hepatitis B virus core protein make multiple contributions to hepatitis B virus replication. Journal of virology. 2014;88:8754–8767. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01343-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann M, Schmitz A, Rabe B. Intracellular transport of hepatitis B virus. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2007;13:39–47. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann M, Sodeik B, Vlachou A, Gerlich WH, Helenius A. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of hepatitis B virus core particles to the nuclear pore complex. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;145:45–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann M, Thomssen R, Kochel HG, Gerlich WH. Characterization of the endogenous protein kinase activity of the hepatitis B virus. Archives of virology. Supplementum. 1993;8:53–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9312-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katen SP, Chirapu SR, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. Trapping of Hepatitis B Virus capsid assembly intermediates by phenylpropenamide assembly accelerators. ACS chemical biology. 2010;5:1125–1136. doi: 10.1021/cb100275b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katen SP, Tan Z, Chirapu SR, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. Assembly-directed antivirals differentially bind quasiequivalent pockets to modify hepatitis B virus capsid tertiary and quaternary structure. Structure. 2013;21:1406–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katen SP, Zlotnick A. Thermodynamics of Virus Capsid Assembly. Methods in Enz. 2009;455:395–417. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04214-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegel WK, Schoot Pv P. Competing hydrophobic and screened-coulomb interactions in hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Biophys J. 2004;86:3905–3913. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RW, Ladner SK, Miller TJ, Zaifert K, Perni RB, Conway SC, Otto MJ. Inhibition of human hepatitis B virus replication by AT-61, a phenylpropenamide derivative, alone and in combination with (−)beta-L-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3179–3186. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock J, Nassal M, Deres K, Blum HE, von Weizsacker F. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsids formed by carboxy-terminally mutated core proteins contain spliced viral genomes but lack full-size DNA. Journal of virology. 2004;78:13812–13818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13812-13818.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniger C, Wingert I, Marsmann M, Rosler C, Beck J, Nassal M. Involvement of the host DNA-repair enzyme TDP2 in formation of the covalently closed circular DNA persistence reservoir of hepatitis B viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4244–4253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409986111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreja AA, Wang JC, Pierson E, Keifer DZ, Selzer L, Tan Z, Dragnea B, Jarrold MF, Zlotnick A. Structurally similar woodchuck and human hepadnavirus core proteins have distinctly different temperature dependences of assembly. Journal of virology. 2014;88:14105–14115. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01840-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan YT, Li J, Liao W, Ou J. Roles of the three major phosphorylation sites of hepatitis B virus core protein in viral replication. Virology. 1999;259:342–348. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pogam S, Chua PK, Newman M, Shih C. Exposure of RNA templates and encapsidation of spliced viral RNA are influenced by the arginine-rich domain of human hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBcAg 165-173). Journal of virology. 2005;79:1871–1887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1871-1887.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pogam S, Shih C. Influence of a putative intermolecular interaction between core and the pre-S1 domain of the large envelope protein on hepatitis B virus secretion. Journal of virology. 2002;76:6510–6517. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6510-6517.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pogam S, Yuan TT, Sahu GK, Chatterjee S, Shih C. Low-level secretion of human hepatitis B virus virions caused by two independent, naturally occurring mutations (P5T and L60V) in the capsid protein. Journal of virology. 2000;74:9099–9105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.9099-9105.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JG, Guo J, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: critical role in reverse transcription and molecular mechanism. Prog. Nucleic. Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 2005;80:217–286. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JG, Mitra M, Mascarenhas A, Musier-Forsyth K. Role of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein in HIV-1 reverse transcription. RNA biology. 2010;7:754–774. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.6.14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levrero M, Pollicino T, Petersen J, Belloni L, Raimondo G, Dandri M. Control of cccDNA function in hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2009;51:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewellyn EB, Loeb DD. Base pairing between cis-acting sequences contributes to template switching during plus-strand DNA synthesis in human hepatitis B virus. Journal of virology. 2007;81:6207–6215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00210-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewellyn EB, Loeb DD. The arginine clusters of the carboxy-terminal domain of the core protein of hepatitis B virus make pleiotropic contributions to genome replication. Journal of virology. 2011a;85:1298–1309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01957-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewellyn EB, Loeb DD. Serine phosphoacceptor sites within the core protein of hepatitis B virus contribute to genome replication pleiotropically. PLoS One. 2011b;6:e17202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Chirapu SR, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. Phase Diagrams Map the Properties of Antiviral Agents Directed against Hepatitis B Virus Core Assembly. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1505–1508. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01766-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Ou JH. Phosphorylation and nuclear localization of the hepatitis B virus core protein: significance of serine in the three repeated SPRRR motifs. Journal of virology. 1995;69:1025–1029. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1025-1029.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Ludgate L, Yuan Z, Hu J. Regulation of Multiple Stages of Hepadnavirus Replication by the Carboxyl-Terminal Domain of Viral Core Protein in trans. Journal of Virology. 2015;89:2918–2930. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03116-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucifora J, Arzberger S, Durantel D, Belloni L, Strubin M, Levrero M, Zoulim F, Hantz O, Protzer U. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential to initiate and maintain virus replication after infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, Sprinzl MF, Koppensteiner H, Makowska Z, Volz T, Remouchamps C, Chou WM, Thasler WE, Huser N, Durantel D, Liang TJ, Munk C, Heim MH, Browning JL, Dejardin E, Dandri M, Schindler M, Heikenwalder M, Protzer U. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science. 2014;343:1221–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1243462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludgate L, Adams C, Hu J. Phosphorylation State-Dependent Interactions of Hepadnavirus Core Protein with Host Factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludgate L, Ning X, Nguyen DH, Adams C, Mentzer L, Hu J. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 phosphorylates s/t-p sites in the hepadnavirus core protein C-terminal domain and is incorporated into viral capsids. Journal of virology. 2012;86:12237–12250. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01218-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Bushman FD. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of the ORF1 protein from the mouse LINE-1 retrotransposon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:467–475. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.467-475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melegari M, Wolf SK, Schneider RJ. Hepatitis B virus DNA replication is coordinated by core protein serine phosphorylation and HBx expression. Journal of virology. 2005;79:9810–9820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9810-9820.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne S, Cote PJ. The woodchuck as an animal model for pathogenesis and therapy of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2007;13:104–124. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller KL. Structural Biology. Molecular “go” signals reveal their secrets. Sci. Signal. 2015;8:ec57. [Google Scholar]

- Nardozzi JD, Lott K, Cingolani G. Phosphorylation meets nuclear import: a review. Cell Commun Signal. 2010;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal M. The arginine-rich domain of the hepatitis B virus core protein is required for pregenome encapsidation and productive viral positive-strand DNA synthesis but not for virus assembly. J.Virol. 1992;66:4107–4116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4107-4116.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal M, Junker-Niepmann M, Schaller H. Translational inactivation of RNA function: discrimination against a subset of genomic transcripts during HBV nucleocapsid assembly. Cell. 1990;63:1357–1363. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90431-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal M, Rieger A. A bulged region of the hepatitis B virus RNA encapsidation signal contains the replication origin for discontinuous first-strand DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1996;70:2764–2773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2764-2773.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal M, Rieger A, Steinau O. Topological analysis of the hepatitis B virus core particle by cysteine-cysteine cross-linking. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:1013–1025. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90101-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal M, Schaller H. Hepatitis B virus replication--an update. J.Viral.Hepat. 1996;3:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1996.tb00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M, Chua PK, Tang FM, Su PY, Shih C. Testing an electrostatic interaction hypothesis of hepatitis B virus capsid stability by using an in vitro capsid disassembly/reassembly system. Journal of virology. 2009;83:10616–10626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00749-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DH, Ludgate L, Hu J. Hepatitis B virus-cell interactions and pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:289–294. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X, Nguyen D, Mentzer L, Adams C, Lee H, Ashley R, Hafenstein S, Hu J. Secretion of genome-free hepatitis B virus--single strand blocking model for virion morphogenesis of para-retrovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002255. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packianathan C, Katen SP, Dann CE, 3rd, Zlotnick A. Conformational changes in the Hepatitis B virus core protein are consistent with a role for allostery in virus assembly. Journal of virology. 2010;84:1607–1615. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02033-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pairan A, Bruss V. Functional surfaces of the hepatitis B virus capsid. Journal of virology. 2009;83:11616–11623. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01178-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman DH, Berg EA, O'Connor P B, Costello CE, Hu J. Reverse transcription-associated dephosphorylation of hepadnavirus nucleocapsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9020–9025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502138102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter JD, Perkett MR, Hagan MF. Pathways for virus assembly around nucleic acids. Journal of molecular biology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perni RB, Conway SC, Ladner SK, Zaifert K, Otto MJ, King RW. Phenylpropenamide derivatives as inhibitors of hepatitis B virus replication. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2000;10:2687–2690. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson EE, Keifer DZ, Selzer L, Lee LS, Contino NC, Wang JC, Zlotnick A, Jarrold MF. Detection of late intermediates in virus capsid assembly by charge detection mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3536–3541. doi: 10.1021/ja411460w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, Ganem D. An RNA stem-loop structure directs hepatitis B virus genomic RNA encapsidation. Journal of virology. 1993;67:3254–3263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3254-3263.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollicino T, Belloni L, Raffa G, Pediconi N, Squadrito G, Raimondo G, Levrero M. Hepatitis B virus replication is regulated by the acetylation status of hepatitis B virus cccDNA-bound H3 and H4 histones. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:823–837. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsel D, Bruss V. Mapping of amino acid side chains on the surface of hepatitis B virus capsids required for envelopment and virion formation. Journal of virology. 2003;77:416–422. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.416-422.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield JZ, Dhason MS, Loeb DD, Nassal M, Stray SJ, Zlotnick A. Full-Length Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein Packages Viral and Heterologous RNA with Similarly High Levels of Cooperativity. Journal of virology. 2010;84:7174–7184. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00586-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield JZ, Zlotnick A. A simple and general method for determining the protein and nucleic acid content of viruses by UV absorbance. Virology. 2010;407:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevelige PEJ. Inhibiting virus-capsid assembly by altering the polymerisation pathway. Trends Biotech. 1998;16:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G, Hu B, Zhou D, Xuan Y, Bai L, Duan C. NIRF, a Novel Ubiquitin Ligase, Inhibits Hepatitis B Virus Replication Through Effect on HBV Core Protein and H3 Histones. DNA Cell Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1089/dna.2014.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G, Jin F, Chang L, Yang Y, Peng H, Duan C. NIRF, a novel ubiquitin ligase, interacts with hepatitis B virus core protein and promotes its degradation. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;34:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Kufareva I, Holden LG, Wang C, Zheng Y, Zhao C, Fenalti G, Wu H, Han GW, Cherezov V, Abagyan R, Stevens RC, Handel TM. Structural biology. Crystal structure of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in complex with a viral chemokine. Science. 2015;347:1117–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1261064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe B, Delaleau M, Bischof A, Foss M, Sominskaya I, Pumpens P, Cazenave C, Castroviejo M, Kann M. Nuclear entry of hepatitis B virus capsids involves disintegration to protein dimers followed by nuclear reassociation to capsids. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000563. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe B, Vlachou A, Pante N, Helenius A, Kann M. Nuclear import of hepatitis B virus capsids and release of the viral genome. PNAS. 2003;100:9849–9854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1730940100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziwill G, Tucker W, Schaller H. Mutational analysis of the hepatitis B virus P gene product: domain structure and RNase H activity. J. Virol. 1990;64:613–620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.613-620.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]