Abstract

Compared to any other racial/ethnic group, Asian Americans represent a population disproportionately affected by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, a leading cause of liver cancer. Since 2007, the San Francisco Hep B Free (SFHBF) Campaign has been actively creating awareness and education on the importance of screening, testing, and vaccination of HBV among Asian Americans. In order to understand what messages resonated with Asian Americans in San Francisco, key informant interviews with 23 (n=23) individuals involved in community outreach were conducted. A key finding was the ability of the SFHBF campaign to utilize unique health communication strategies to break the silence and normalize discussions of HBV. In addition, the campaign’s approach to using public disclosures and motivating action by emphasizing solutions towards ending HBV proved to resonate with Asian Americans. The findings and lessons learned have implications for not only HBV but other stigmatized health issues in the Asian American community.

Keywords: Hep B, Asian American, San Francisco, Stigma, Health communication

As a racial/ethnic group, Asian Americans have by far the highest rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, a leading cause of liver cancer [1]. Less than 1% of general US population has hepatitis B; however, it is estimated that one in ten Asian Americans are infected [2]. The city and county of San Francisco has the highest rate of liver cancer in America and a disproportionate burden of undetected HBV infection due to the large Asian American population (about one third [3]) and high rates of HBV infection [4]. Seeking to reduce the rate of and increase treatment for hepatitis B infection in the San Francisco Bay Area, starting in 2007, the San Francisco Hep B Free (SFHBF) Campaign drew together a comprehensive coalition of key leaders and organizations from media, health care, government, community, and business sectors within and beyond the Asian American community.

The key priorities of the SFHBF campaign are (1) to create public and health care provider awareness about the importance of testing and vaccinating Asian Americans for hepatitis B, (2) to promote routine hepatitis B testing and vaccination within the primary care medical community, and (3) to ensure access to treatment for chronically infected individuals. SFHBF has created and implemented a dual-pronged comprehensive media campaign to communicate (a) Asian American-targeted screening, vaccination, and treatment messages and (b) broader awareness messages that raise consciousness and support in general society and mainstream institutions.

SFHBF Campaign: Delivering the Message Through PSAs

Taking lessons from other health movements impacting subpopulations in the USA (e.g., HIV/AIDS and breast cancer), SFHBF organizers were determined to utilize unique characteristics of Asian American communities to create an effective health care movement. SFHBF started with no funds nor identified funding sources. Individuals donated time, and organizations donated staff and office support. In one of their first actions, organizers gained strong public statements of support from two of the highest level officials in San Francisco: Mayor Gavin Newsom and then Supervisor Fiona Ma (then the only Asian American supervisor in the city) giving legitimacy to the campaign. Ma helped break down the stigma surrounding hepatitis B through her willingness to talk publically about her own chronic HBV infection. Mayor Newsom made it his goal for San Francisco to be free of hepatitis B and to serve as a public health model for the nation.

In spring 2007, bus signs and billboards with images of Ma and Newsom introduced San Franciscans to the SFHBF campaign and the concept of getting tested. With Asian Americans living and working throughout San Francisco, the ad campaign implemented an innovative combination of mainstream media that included select billboards in Asian American neighborhoods and on those transit lines with high Asian American ridership. The ads featured three large images: Mayor Newsom, Assemblywoman Ma, and the SFHBF logo. A simple message stated “B Sure. B Tested. B Free.”

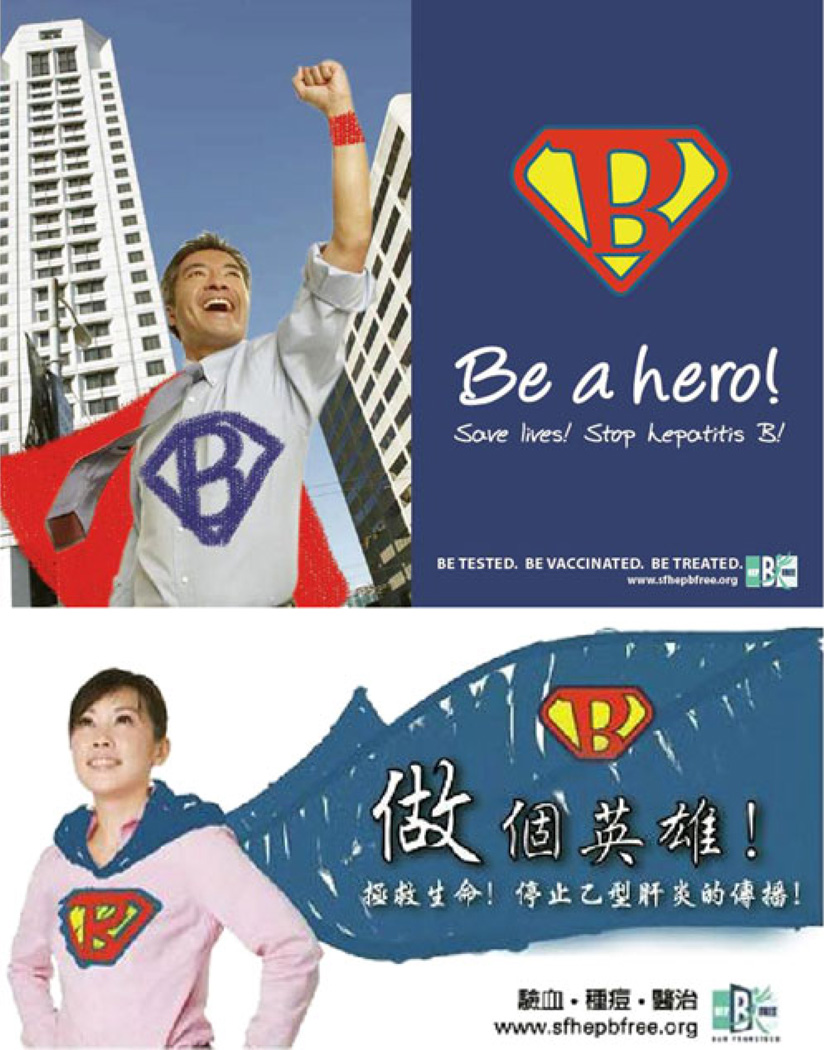

In 2008, the “B a Hero” ad campaign featured Asian Americans with drawn cape and Superman hero costumes superimposed on their everyday clothing, with a “B” appearing in place of the Superman “S.” The concept was that anyone could be a hero by getting tested for HBV and talking to friends and family about being tested. The “B a Hero” logo easily translated to t-shirts, media outreach, flyers, and capes. An annual “B a Hero” award, including a crystal sculpture and a superhero cape, were awarded at the annual “B a Hero” gala. This campaign presented a positive, upbeat approach to destigmatize the issue among Asian Americans.

Launched in 2009, the third phase of the advertising strategy was the “Which One Deserves to Die?” campaign. This campaign broke new ground in messaging for Asian Americans, utilizing virtually all forms of media including television, radio, print, outdoor, and social media (see Fig. 1). The campaign leveraged cash to in-kind contributions, garnering five times the media coverage for every dollar spent. All 60 models (ten models each in six versions of the ad) were local volunteers representing a diverse range of Asian ethnicities. The use of people from the community helped foster a sense of community pride in a historical community movement.

Fig. 1.

San Francisco hep B free 2008–2009 outreach campaign: B A Hero poster

Unlike the “B a Hero” campaign, the message, “Which One Deserves to Die?” was designed to motivate people to take action and get tested by speaking to the seriousness of the disease (see Fig. 2). Two 30-s public service announcements (PSAs) were developed. One features Asian American beauty pageant contestants. The voice-over asks, “Out of these ten women, which one deserves to die?” As the voice-over continues, saying, “One in ten Asian Americans is infected with hep B, the leading cause of liver cancer,” the camera pans in onto the women’s faces as they look startled and frightened. Then, a light bulb in a chandelier turns on while the voice says, “but hepatitis B can be treated, even prevented. Get tested. Stop liver cancer by stopping hepatitis B.” The second commercial is an Asian American intergenerational family getting ready to take a formal family photo. The messaging is the same as above. The ads end showing the text of the campaign slogan, “B a Hero. See a Doctor Who Tests for Hep B.”

Fig. 2.

San Francisco hep B free 2010 outreach campaign posters

Educational, Entertaining, and Culturally Sensitive Narratives and Respected Leaders

This is the first research study examining the role of influential Asian American leaders, celebrities, and others in health promotion campaigns. According to Valente and Pumpuang (2007), opinion leaders in a community can serve vital functions in a health campaign, including providing legitimacy to other influential individuals, entities, and organizations to get involved, serving as role models for behavior change and conveying health messages [5]. A key practice of SFHBF has been the use of visible and highly respected voices in San Francisco’s Asian American community, ranging from community and political leaders, to celebrities and physicians. SFHBF is also the first effort to use a “narrative” approach to engage Asian Americans. Studies have shown that narrative communication is becoming an important tool for health campaigns generally [6]. According to Schank and Berman (2002), narrative communication can take multiple different forms—including official stories, invented stories, and personal stories—to educate about a particular health issue [7]. In racial and ethnic minority communities, personal experience narratives have been shown to be effective in promoting cancer screenings as demonstrated in the Witness Project, a program in which local African-American breast and cervical cancer survivors, called “witness role models,” talk about, or “witness,” their cancer experiences. Women who participated in such “witnessing” had increased “buy in” to the program because the “witness role models” were from the community and shared similar cultural values and understandings [8, 9].

Previous work on Asian Americans and hepatitis screenings has shown that sources of messages make a difference in how the targeted audience responds. For example, in a study comparing community mobilization versus media campaigns in a campaign to promote hepatitis B vaccinations among Vietnamese-American children, investigators found that both media education and community mobilization successfully increased the number of Vietnamese-American children vaccinated [10]. Others have used community health promoters and lay health workers [10]; student-led educational workshops [11]; low-cost, affordable screening, and vaccinations [12]; and direct mailings of audiovisual and print materials [2, 10]. Although the effectiveness of these particular interventions has been studied, there is a lack of in-depth analysis on health communication and narrative practices used to effectively outreach to Asian Americans.

Methods

This study primarily sought to determine what messages and modes of communication regarding screening, testing, and vaccination about the hepatitis B virus have resonated with the San Francisco Asian American community. Twenty-three (n=23) individuals, including community members, health care providers, media and political leaders, and leaders of Asian American community organizations were interviewed about and their thoughts on effectiveness and best practices in terms of health communication strategies of the SFHBF campaign. The interviews were tape-recorded and then fully transcribed. In the first iteration of qualitative analysis, the data were coded using grounded theory analytical methods [13] to identify themes, trends, and patterns about the successes and challenges of the health messages presented by the SFHBF campaign.

Results

According to these key informants, this campaign proved successful in moving community views of hepatitis B from stigmatized taboo to a community-wide health and wellness cause. Several themes occur repeatedly across the interviews and in the field notes, including destigmatizing and depersonalizing hep B to be not about bad people or bad behavior, utilizing public disclosures as an avenue to disseminate this message, emphasizing that “We” and “You” can effect change and connecting individual and collective actions.

Destigmatizing Hep B: Not About Bad People or Bad Behavior

In many Asian countries, infected patients are acculturated to feel ashamed or fearful, and consequently hide their disease. SFHBF aggressively reframed the discourse through factual information on transmission, emphasizing medical solutions, and creating positive emotions and feelings of empowerment.

According to key informants, a major challenge in overcoming stigmatization is the association in Asia of hepatitis B with “bad people” and “bad behavior.” The common presumption in Asia is that those infected somehow deserve it. This cultural stigma can carry over to Asians in America, causing social exile for those with and creating silence around hepatitis B. San Francisco Board of Supervisors President David Chiu suggests that SFHBF shifted this paradigm by providing multiple opportunities for the Asian American community to talk about hepatitis B openly and educationally:

I think addressing the stereotype that somehow people who get hepatitis are bad people or that it’s sexually transmitted to only certain populations is important. And I think because of that, there’s a cultured stigma within our community to not talk about it. And I think what we’ve done is bring it out of the closet. We’ve explained that it is a disease that you can pick up from many places.

Chiu, whose supervisorial district includes Chinatown, cites the power of SFHBF to destigmatize hepatitis B by teaching people to teach others that hepatitis B is not simply transmitted by “bad behavior.” Francis Tsang, an aide to then San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, drew comparisons with other stigmatized diseases:

It is something that has a lot of stigma like HIV AIDS and some cancers, you have these stigmas about Hep B; when you start talking about the stigmas it’s removed a little bit because people are talking about it being treatable or preventable, not curable, but …it’s something we can eliminate over time.

Destigmatization is not only a first step, but is also a process that needs to be continually reiterated. Jason Liu, an activist and premedical student, says that even when educating Asian Americans that their primary mode of hepatitis B infection is from fluids transferred during the birthing process, the stigma is still difficult to eradicate given that hepatitis B can be transmitted sexually or through drug use. Liu says changing this stigma requires a multilevel, continually reinforced process because people are “afraid of being stigmatized by the message. So, even though we talk about getting screened, and it’s important for stopping liver cancer, there is still stigma.”

Moving Stigma Aside: Utilizing Public Disclosures

All key informants discussed the importance of well-known and respected Asian Americans speaking out; by virtue of their media presence or political standing, they influence community leaders and members to see hepatitis B as a significant and an urgent issue. Many said personal disclosures by well-known Asian Americans such as California Assemblywoman Fiona Ma and local ABC affiliate news anchor Alan Wang destigmatized hepatitis B. These two individuals’ highly public and positive stories put the San Francisco Hep B Free campaign at the forefront of the minds of local Asian Americans.

Assemblywoman Ma has been featured in stories, events, and ads as someone living with hepatitis B. Supervisor Chiu cited this as an important factor in shifting attitudes about hepatitis B: “putting… people who have the disease who speak up, has been remarkably effective. Saying, ‘Hey Fiona Ma has it,’ is, I think, probably the most powerful.” Mayoral aide Tsang adds

I see Fiona Ma being the poster child for hep B, you know, since she’s infected with hep B; also, I think that the focus of celebrating Asian Americans with Asian American Heritage month is raising awareness about hep B.

Ma herself has seen the impact of publicly sharing her story: “Some people have said, ‘You saved my life because I didn’t know I had it, and now I’m able to treat it before it got too late.’” She adds, “For Asians, [often,] their relatives have died from it, they didn’t know why, maybe. And now they’re actually going to get tested and screened and making sure their family members are doing it. So I feel good about that.” Ma believes in using her political office to be a voice to serve the community. She says, “I talk about anything and everything and I think it’s why I’m in an elected office, and I should use my position to be a voice. Otherwise, why bother being here?”

Jeanette Tam, who works for a health plan focused on Chinese-Americans, also cites Ma’s impact, saying, “this is not something that Chinese people and Chinese families discuss: weaknesses. And so with Fiona Ma coming out and talking about that, it was an eye opener to me.” That a public figure would risk her public image coming forward impressed Tam enough to encourage her to speak up as well. Tam states, “And even if you choose to tell someone to get prevention, get tested, and get vaccinated, that’s good. And if it goes as far as, ‘You know what? I’m going through it too,’ it puts a human face on it so that people don’t have to feel secretive.” Each disclosure has helped others to find courage to take action. Alan Wang reveals that he was inspired to open up about his hep B status by Fiona Ma and her openness to share:

It was very shocking to me. But that is what dawned on me, …because I have kind of hidden behind it myself. As a news anchor, as a public figure, I was afraid—it’s very similar to AIDS in many ways…. [Now] I have spoken about it on the air, I’ve covered stories with it, and actually kind of given a full disclosure in my story explaining my situation and my family.

In an on-air piece, Wang described discovery of his own infection status, and his on-going monitoring and treatment to prevent liver cancer. He has proven to be a key resource and voice for the campaign by talking about his hepatitis B infection openly. Dr. Ed Chow, medical director of the Chinese Community Health Plan, says these public disclosures have been monumental: “the fact that we can now talk about hepatitis B and have it as an open discussion and that there is opportunity for prevention.”

Motivating Action by Emphasizing Solutions: We Can Do Something About This!

According to key informants, focusing on the message that this is a problem that can be solved has encouraged greater involvement by members of the community. This is coupled with the message that up to two thirds of infected Asian Americans who are infected are unaware of their disease and potential for liver cancer. Thus, a start to destigmatization and action involves making clear that this disease can be prevented through combined community efforts. SFHBF’s “B a Hero” campaign was built around the idea that addressing hepatitis B is a heroic cause and that “we,” everyday people, can make a difference. Chinese Hospital’s Dr. Stuart Fong states, “We want people to be a hero. … getting themselves tested, knowing their status and if they need to be vaccinated to get vaccinated.” Being proactive as individuals is important, but the “B a Hero” campaign also considers the importance of encouraging family members to get screened, tested, and vaccinated.

Another best practice of this campaign, according to respondents, is refocusing attention onto solutions such as vaccination and treatment availability and shifting the paradigm of the disease away from the impression that it is a death sentence. Thus, the taboo against discussing “bad news,” especially news related to death, can be subverted by the message that the community working together can prevent hepatitis b disease and liver cancer. Through it all, Dr. Chow emphasizes the importance of providing a way for Asian Americans to discuss it and credits the campaign with doing so. He states:

The fact that … there is opportunity for prevention, I think that’s a very important message that … allows hep B to be discussed. And then the fact that … by identifying a carrier and then placing them on observation and treatment if necessary we can avoid liver failure or liver cancer.

Several participants mentioned that hepatitis B has been “destigmatized” by developing the message that something could be done to stop hepatitis B disease. According to Asian American community activist Mary Jung:

Here was something that we could actually do something about. Sort of like malaria, like back last century. Or polio where people just made a concerted effort. And you know, almost eradicated it, right? Unlike many other illnesses, the negative effects of hepatitis are preventable with the concerted effort of education. So hepatitis B is one of these ones where you say, ‘Okay, it affects a large part of the Asian population… you can actually do something about it.’

Jung says the ability of individuals working together to make a difference gives participants a positive outlook: “Isn’t it nice to work on something that’s preventive? …. Instead of always earning money for research like for cancer, or something like that.” Jung’s attitude reflects a high level of enthusiasm for the belief that everyone has the opportunity to become a hero. It also contributes to the powerful energy driving the SFHBF campaign and is driven itself by the possibility that one of the deadliest diseases facing Asians and Pacific Islanders—liver cancer—can come to an end through community-wide collaboration.

The fact that hepatitis B can be prevented and controlled means it can be seen as different from cancer, which many Asian Americans associate with a death sentence. Peter Swing says

It’s vaccine preventable, it’s treatable. And so it’s almost like .… it’s the cure for liver disease, liver cancer. Who’s not going to take that up? …Why aren’t people going to get involved if it’s something that you can do so easily in relation to, … diabetes for example, HIV, and AIDS? Those are diseases that don’t have a ‘cure’.

The executive director of the Asian American Theater Company, Darryl Chiang, agrees:

There should be very low barriers to people actually resolving the situation and if we work together we can do a lot to stop the spread of it. If we all took action collectively, that would solve the problem pretty easily.

Many respondents indicated it has been easier to destigmatize among Asian Americans born or raised in the USA, as opposed to those who are first generation adult immigrants. Although preexisting barriers and stigma affect many Asian immigrants, respondents suggested that through SFHBF, US-born Asian American were better able to communicate across generations the importance of addressing hepatitis B. Swing sees global implications, suggesting “that Asian American can be the conduit, the link of providing that knowledge to other Asians. …And I think Asian Americans doing work in hepatitis B can definitely translate that across overseas to places like China.”

Discussion

This key informant study illustrates how SFHBF used multiple approaches to destigmatize hepatitis B. Although there is little information on Asian Americans and health communication practices, according to Hinyard and Kreuter [15], in order for health communication to be culturally tailored and effective in racial/ethnic minority communities, it must include packaging the campaign, demonstrating the importance of the illness/disease to the community, and delivering the messages in culturally meaningful ways that appeal to the community [14]. The SFHBF Campaign incorporated many of these components including packaging and evidence that would appeal to Asian Americans.

SFHBF ran the first major US market ad campaign featuring all Asian American models. Ethnic and general media campaigns were closely coordinated in five languages, but primarily in English and primarily through general market outlets. By highlighting that one in ten Asian Americans were infected by hep B, this campaign demonstrated that this was indeed a community issue. Moreover, images were presented in Asian American social and cultural contexts. SFHBF outreach focused on developing multilevel strategies for reaching different generational levels as appropriate linguistically and culturally, but with messages that could be discussed and shared within the family unit.

The campaign also used narrative as a powerful form of health communication to reach Asian Americans. Respected leaders such as State Assemblywoman Ma and widely known local broadcaster Wang both provided public faces and offered personal narratives to talk about hepatitis B. Ma and Wang shared their fears and concerns and talked about the steps they took to protect their own their families’ health. Further, they each encouraged Asian American community members to become hep B heroes. Stories of everyday community members were also emphasized through a speaker’s bureau and by featuring everyday community members in ads like the “B a Hero” campaign.

The “B a Hero” slogan emphasized that ordinary members of the Asian American community can make a difference in ending hepatitis B. The message jump-started a community-wide discourse on hepatitis B, while the next campaign, “1 in 10: Which One Deserves to Die?” was designed to provoke action by featuring groups of ten smiling Asian Americans—pageant queens, family reunion photos, etc.—superimposed with the bold question, “Which One Deserves to Die?” The campaign also informs the public that, starkly contrasting with the infection rate of one in 1,000 in the general population, one in ten Asian Americans is chronically infected with hepatitis B. Respondents point to this evolutionary aspect of SFHBF messaging as part of its effectiveness.

SFHBF continually updated health communication practices and messages to reflect the dynamic and diverse nature of the Asian American community and to reflect how the community processes information. Key messages that resonated with Asian Americans included reframing of the hepatitis B narrative away from the stigma of “bad behavior,” to the normalization of hepatitis B discourse with public stories from high profile and ordinary people talking about their hepatitis B status, and finally, the idea that the Asian American community working collectively could effect an end to the scourge of hepatitis B and related liver cancer.

Implications

This study illustrates the importance of utilizing both Asian American opinion leaders and everyday community members. The findings also illustrate the importance of how messages around health promotion are conveyed. For example, respected leaders and local celebrities serve as models by sharing their experiences and also by demonstrating to the community that action can be taken to prevent hepatitis B infection. These role models play a key factor in normalizing and destigmatizing discussions within the community on the importance of testing, vaccination, and follow-up care. Other racial/ethnic minority communities such as African-Americans have used similar approaches [16]. In 1991, when Magic Johnson came out about being HIV positive, he provided a way for many African-Americans to talk about HIV [16].

The SFHBF Campaign may provide a new model for community organizing around health care issues in the Asian American community. A constellation of partnerships created one of the first health movements focused on Asian Americans in the nation. Ultimately, this social movement has changed how hepatitis B is perceived by Asian Americans. The key elements include (1) destigmatizing, (2) utilizing public disclosures, and (3) motivating action by emphasizing solutions. This campaign has implications for various racial/ethnic communities who are working to destigmatize illnesses and diseases. Moreover, it has implications for the Asian American community working on difficult health issues or concerns that are still heavily stigmatized including cancer and mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention grant number 5U58DP001022-03 awarded to the B Free CEED: National Center of Excellence in the Elimination of Hepatitis B Disparities at NYU School of Medicine. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We also thank Kira Donnell in her assistance with transcription of these key informant interviews.

Contributor Information

Grace J. Yoo, Email: grace.yoo.phd@gmail.com, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Ted Fang, Asian Week Foundation, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Janet Zola, San Francisco Department of Public Health, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Wei Ming Dariotis, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Kwong SL, Stewart SL, Aoki CA, et al. Disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma survival among Californians of Asian ancestry, 1988 to 2007. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(11):2747–2757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang ET, Sue E, Zola J, et al. For life: a model pilot program to prevent hepatitis B virus infection and liver cancer in Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(3):176–181. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071025115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Census Bureau. 2006–2008 American Community Survey 3-year estimates. 2009 http://www.census.gov/acs/www/index.html.

- 4.Bailey M, Shiau R, Zola J, et al. San Francisco hep B free: a grassroots community coalition to prevent hepatitis B and liver cancer. Journal of Community Health. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9339-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valente TW, Pumpuang P. Identifying opinion leaders to promote behavior change. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(6):881–896. doi: 10.1177/1090198106297855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(3):221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schank RC, Berman TR. The pervasive role of stories in knowledge and action. In: Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC, editors. Narrative impact: social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts RC, et al. Increasing mammography and breast selfexamination in African American women using the Witness Project model. J Cancer Educ. 1996;11(4):210–215. doi: 10.1080/08858199609528430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts RC, et al. Increasing mammography practice by African American women. Cancer Pract. 1999;7(2):78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, Euler GL, et al. Successful promotion of hepatitis B vaccinations among Vietnamese-American children ages 3 to 18: results of a controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 Pt 1):1278–1288. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu CE, Liu LC, Juon HS, et al. Reducing liver cancer disparities: a community-based hepatitis-B prevention program for Asian American communities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(8):900–907. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheu LC, Toy BC, Kwahk E, et al. A model for interprofessional health disparities education: student-led curriculum on chronic hepatitis B infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):140–145. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu CE, Zhang G, Yan FA, et al. What made a successful hepatitis B program for reducing liver cancer disparities: an examination of baseline characteristics and educational intervention, infection status, and missing responses of at-risk Asian Americans. J Community Health. 2010;35(3):325–335. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory, procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(5):777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mays VM, Flora JA, Schooler C, et al. Magic Johnson's credibility among African-American men. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(12):1692–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.12.1692-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]