Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that microRNAs, small, non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression, may play a role in the regulation of metabolic disorders, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). To identify miRNAs that mediate NAFLD-related fibrosis, we used high-throughput sequencing to assess miRNAs obtained from liver biopsies of 15 individuals without NAFLD fibrosis (F0) and 15 individuals with severe NAFLD fibrosis or cirrhosis (F3-4), matched for age, sex, BMI, T2D status, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications. We used DESeq2 and Kruskal-Wallis test to identify miRNAs that were differentially expressed between NAFLD patients with or without fibrosis, adjusting for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction. We identified a total of 75 miRNAs showing statistically significant evidence (adjusted P-value <0.05) for differential expression between the two groups, including 30 upregulated and 45 downregulated miRNAs. Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis of selected miRNAs identified by sequencing validated nine out of 11 of the top differentially expressed miRNAs. We performed functional enrichment analysis of dysregulated miRNAs and identified several potential gene targets related to NAFLD-related fibrosis including hepatic fibrosis, hepatic stellate cell activation, TGFB signaling, and apoptosis signaling. We identified FOXO3 and FBXW7 as potential targets of miR-182, and found that levels of FOXO3, but not FBXW7, were significantly decreased in fibrotic samples. These findings support a role for hepatic miRNAs in the pathogenesis of NAFLD-related fibrosis and yield possible new insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying the initiation and progression of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a spectrum of conditions resulting from excessive accumulation of fat in hepatocytes (i.e., steatosis) not due to overconsumption of alcohol. Obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and insulin resistance often contribute to the development of NAFLD and many patients with these disorders will have increased hepatic fat storage, a condition known as steatosis. A subset of these patients will also develop steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and/or cirrhosis, collectively representing nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), an advanced form of NAFLD that is associated with increased liver-related morbidity and mortality [1]. NAFLD can be categorized into nonalcoholic fatty liver representing hepatic steatosis and NASH [2]. Although clinical outcomes for NAFLD patients with coincident hepatocyte injury, liver inflammation, and fibrosis are substantially worse compared to those with hepatic steatosis [3,4], there are currently no accurate laboratory measurements or clinical characteristics that predict disease severity in NAFLD patients. In addition, the molecular mechanisms contributing to the heterogeneous outcomes of NAFLD remain poorly understood. At present, the ability to predict which NAFLD patients are more likely to develop coincident inflammation and fibrosis and/or cirrhosis is limited by an incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis underlying progression to more severe manifestations of the disease.

NAFLD can develop in response to environmental and genetic factors, and recent studies also suggest a strong role for epigenetic influences, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) in the pathogenesis of the disease. MiRNAs are endogenous, single-stranded RNAs that regulate gene expression primarily through post-transcriptional mechanisms, and less commonly via transcriptional targeting of the promoter region [5]. In humans, miRNAs silence the expression of target genes predominantly at the post-transcriptional level by imperfectly base-pairing to the 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to translational inhibition and/or mRNA deadenylation and decay [5]. Several miRNAs have been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD in animals. Expression levels of miR-122, miR-451, miR-27a, miR-429, and miR-200a/b were dysregulated in rats with diet-induced NASH compared to animals fed a standard diet [6]. Altered levels of several miRNAs, including miR-146a, miR-210, miR-29c, miR-103, miR-20b-5p, miR-106b, miR-212, miR-31, miR-10a, miR-203, miR-27b, miR-199a, miR-107, let-7b, miR-33, miR-145, miR-196b, miR-93, let-7d, and miR-19 were found to differentiate between steatohepatitis and steatosis in diet-induced NASH [7]. Other studies in animals have identified a number of miRNAs associated with NAFLD and related outcomes [8-14]; however, very few miRNAs have been replicated across studies. Discrepancies in findings are most likely due to differences in dietary composition and regimen, phenotypic endpoint, and strain of animal used.

In humans, investigations of NAFLD-related miRNAs have been conducted using both liver tissue and serum. In one of the first studies of NAFLD-related miRNAs, Cheung et al [15] observed differences in hepatic levels of miR-34a, miR-146b, and miR-122 between patients with NASH and individuals with normal liver histology, although none of these miRNAs were associated with differences in disease severity. Another investigation of 84 circulating miRNAs reported up-regulated serum levels of miR-122, miR-192, miR-19a/b, miR-125b, and miR-375 in patients with either simple steatosis or NASH [16]. However, like the results from animal studies, there has been little replication of findings across studies in humans. Some of the inconsistencies among findings may be attributed to differences in study design and/or method of statistical evaluation, as well as clinical variability between cases and controls. In addition, different microarrays interrogate different populations of miRNAs, oftentimes resulting in limited overlap between studies.

High throughput sequencing approaches circumvent the limitations of microarrays by providing unbiased measurements of expression levels of all miRNAs, known and unknown. To date, a high throughput sequencing strategy has not yet been implemented in the discovery of NAFLD-relevant miRNAs, although such an approach represents a powerful strategy for identifying new candidates related to the disease process. We undertook this study, therefore, to determine whether any previously uncharacterized miRNAs contribute to the development of NAFLD-related fibrosis, focusing on this particular phenotype to lessen the potential impact of clinical variability from more heterogeneous, intermediate levels of fibrosis. We performed miRNA-sequencing in a well-characterized group of individuals with (F3-4) and without (F0) advanced NAFLD fibrosis, matched for age, sex, BMI, T2D status, HbA1c, and diabetes medication use. We observed several miRNAs showing statistically significant evidence for differential expression between cases and controls, and validated a number of candidates showing the strongest changes using quantitative PCR. The findings reported here are concordant with a role for miRNAs in mediating changes that accompany the development of fibrosis in NAFLD patients.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

Study participants were comprised of Caucasian individuals enrolled in the Bariatric Surgery Program at the Geisinger Clinic Center for Nutrition and Weight Management. All research participants have undergone a standardized, multi-disciplinary pre-operative program in which a large amount of clinical data and biospecimens were collected [17]. In all participants, wedge biopsies of the liver were obtained intraoperatively from similar anatomic locations. The tissue was sectioned so that one-fourth to one-third of it was submerged directly in RNAlater (Applied Biosystems/Ambion; Austin, TX) and stored at −80°C for subsequent miRNA sequence analysis, and th e remainder was fixed in neutral buffered formalin, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and histologically evaluated as part of clinical standard of care using NASH CRN criteria [18], as previously described [19]. Patients with histologic or serologic evidence for other chronic liver diseases were excluded from this study. Clinically significant alcohol intake was determined via a 1–2 hour comprehensive clinical interview and psychological evaluation that were conducted by certified psychology professionals and included a multi-question determination of drugs, alcohol, and smoking behaviors. Patients who were assessed to manifest either definite or possible evidence of addictive behaviors were not allowed to proceed to surgery. In addition, we also evaluated available clinical data, including diagnostic ICD-9 codes, medical, and medication history, for any indication of drug or alcohol abuse, and if identified, those patients were removed from the study. Following medical history, psychological evaluation, and histological assessment, individuals with clinically significant alcohol intake and drug use were also excluded from participation in the program.

Variables were obtained from an electronic database as described previously [20], and included basic clinical measures, demographics, diagnostic ICD-9 codes, medical and medication history, and common lab results. Individuals were selected for inclusion in the sample based upon histologically defined liver fibrosis stage. Cases were defined by the presence of liver fibrosis stage 3 or 4 (F3-4), while controls were defined as those showing no evidence of liver fibrosis (i.e., liver fibrosis stage 0 or F0) and were otherwise histologically normal. Cases and controls were matched for sex, age, BMI, T2D status, HbA1c levels, and use of diabetes medications (33% of F0 and 67% of F3-4 patients were taking diabetes medications at the time of biopsy). Demographic data and laboratory measures were obtained from all patients at the time of liver biopsy. The research was carried out according to The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), all participants provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Boards of the Geisinger Clinic and the Translational Genomics Research Institute approved the research, and all participants provided written informed consent.

miRNA sequencing analysis, quality control, quantification, and normalization

Frozen liver tissue from 30 NAFLD patients with stage F0 or F3/4 fibrosis was minced and resuspended in Cell Disruption Buffer from the mirVana PARIS RNA and Native Protein Purification Kit (Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and then homogenized in conjunction with a S220 ultrasonicator (Covaris, Inc; Woburn, MA). We extracted miRNA using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol and quantified products using the Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies) prior to sequencing. We sequenced samples using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina; San Diego, CA) sequencing platform for miRNA-Seq. Small RNA libraries were loaded onto the sequencer and sequenced for 50 cycles on a single-read flowcell. One lane of the flowcell was dedicated to a PhiX control to account for the low amount of nucleotide diversity in small RNA samples and to allow for the calculation of phasing and pre-phasing of the sequenced sample. Samples were sequenced to the same approximate depth/number of reads to allow quantitative comparisons to be made between samples. Sequencing data were processed using the Illumina pipeline CASAVA v1.8.2 to generate raw fastq reads. We performed quality control checks on raw sequence data using the FastQC tool [http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc]. All data passed FastQC quality check. To ensure that fastq reads were in normal range (green tick ≥Q28), we discarded reads containing sequencing errors. We also performed other pre-alignment processing steps (i.e., adapter clipping and read collapsing) using the FASTX toolkit [http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit]. Following quality checks, we discover that two F0 samples did not yield usable data and three F0 samples showed a low number of mapped reads (<100,000). These five samples were removed from further analysis.

We used the miRDeep2 software package for the identification of novel and known miRNAs from deep sequencing data [21]. We used the Mapper module to process raw sequences and map processed reads to the reference genome (GRCh37/hg19). Once aligned, the miRDeep2 module excised genomic regions covered by the sequencing data to identify probable secondary RNA structure. Potential precursors were evaluated and scored based on their likelihood of being genuine miRNAs. The Quantifier module produced a scored list of known and novel miRNAs with quantification and expression profiling. We used recommended default parameters and allowed one single nucleotide variation.

We measured the expression level of miRNAs generated by high throughput sequencing as the number of sequenced fragments mapping to the miRNA transcript, which we expected to correlate directly with its abundance level. To identify miRNAs that were differentially expressed, we used DESeq2 [22] and Kruskal-Wallis, comparing F0 and F3-4, and adjusting for age, T2D status, HbA1c, and BMI. We corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. The level of statistical significance, represented by corrected p-value, and the degree of fold-change were used to identify miRNAs showing the strongest differential expression between phenotypic categories.

Analysis of individual miRNAs using quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

To analyze individual miRNAs, we performed RT-qPCR using miRNA from the same liver samples used in miRNA-sequencing. We converted miRNA to cDNA using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Life Technologies). We assessed miRNA levels using TaqMan MicroRNA Assay primers in conjunction with ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detector apparatus (Life Technologies). Assay names and mature sequences for the validated miRNAs are shown in Table S1. All assays were performed in triplicate. Cycle threshold values were generated using Expression Suite Software v1.0 (Life Technologies) and means were normalized against miR-26a, which showed stable levels among all samples. The -ΔΔCt method was used to determine fold-change of miRNA expression between samples.

Validation of FOXO3 and FBXW7 transcript and protein levels

For prediction of target genes for miR-182, we interrogated the miRanda [23,24], miRWalk [25], and miRTarBase [26] databases and used a combination of overlap analysis, relevance to liver fibrosis, and literature-mining to select specific genes for functional analysis. We performed first-strand cDNA synthesis from 100 ng of total RNA using the TaqMan RNA-to-Ct 1-Step kit and TaqMan Gene Expression Assays according to the manufacturer's protocol, followed by qPCR analysis as described above. Ct values of FOXO3 and FBXW7 were normalized using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

We determined protein concentrations in tissue lysate preparations using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific). We used a commercial sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cusabio; Wuhan, China) to determine concentrations of FOXO3 and FBXW7 protein in liver tissue lysate.

Pathway and functional enrichment analysis

We used the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software (IPA, Qiagen; Redwood City, CA; www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) to identify canonical signaling pathways and establish network connections between all dysregulated miRNAs and their respective predicted targets. The miRNA target prediction was limited to experimentally validated targets in humans present in the IPA library (Inequity Expert Findings, Inequity ExpertAssist Findings, miRecords, TarBase, TargetScan Human) and expressed in liver tissue. The significance of the association between miRNA targets and the canonical pathway was assessed using two criteria: 1) the ratio of the number of molecules mapped to the pathway and total number of molecules involved in the canonical pathway and 2) the Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-value from the right-tailed Fisher Exact test.

Results

Study sample characteristics

Two groups of biopsy-proven NAFLD patients comprised the study sample: 15 individuals with stages 3 and 4 (F3-4) of NAFLD fibrosis and 15 without fibrosis (F0). The demographic data and clinical characteristics of the NAFLD patients comprising the study sample are shown in Table 1. As expected, individuals with NAFLD fibrosis had higher levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) compared to individuals without fibrosis. Fibrosis cases also had significantly higher levels of insulin and triglycerides compared to controls. Histologic features representing disease severity showed significant differences between the two groups. NAFLD patients with fibrosis had greater lobular inflammation, portal inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning compared to individuals without fibrosis.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| F0 (N=15) | F3-4 (N=15) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 15 (1.00) | 15 (1.00) | NS |

| Mean age in years at biopsy (SD) | 47.1 (6.3) | 51.3 (8.2) | NS |

| BMI at biopsy (SD) | 41.0 (4.6) | 44.4 (6.6) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (0.40) | 6 (0.40) | NS |

| Laboratory measures, mean (SD) | |||

| Serum AST, U/L | 23.2 (4.2) | 47.5 (23.3) | .0004 |

| Serum ALT, U/L | 23.7 (8.1) | 47.3 (26.5) | .0027 |

| AST/ALT, U/L | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | NS |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 71.2 (15.9) | 91.6 (80.5) | NS |

| Total bilirubin | 0.49 (0.24) | 0.47 (0.18) | NS |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 100.9 (31.9) | 120.2 (53.5) | NS |

| Insulin | 18.0 (13.2) | 39.7 (29.8) | .0155 |

| HbA1c, % (SD) | 6.0 (1.0) | 6.6 (1.3) | NS |

| Triglycerides | 142.9 (64.5) | 186.9 (67.2) | 0.04 |

| Total cholesterol | 179.7 (26.1) | 197.9 (33.9) | NS |

| LDL-C | 107.3 (14.4) | 116.5 (17.2) | NS |

| HDL-C | 55.9 (28.3) | 46.7 (32.4) | NS |

| Histologic characteristics | |||

| Steatosis, mean grade (SD) | 0 | 2.1 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Lobular inflammation, %=grade 1 | 0 | 0.47 | <0.0001 |

| Lobular inflammation, %>grade 2 | 0 | 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Portal inflammation, (%) | 0 | 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Ballooning (mean score) | 0 | 1.3 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

Differentially expressed hepatic miRNAs NAFLD-related fibrosis

We utilized high throughput sequencing to examine differences in hepatic miRNA expression between 15 F0 and 15 F3-4 NAFLD patients. Of these, two F0 samples did not yield usable data and three F0 samples were removed due to a low number of mapped reads (<100,000). Therefore, the total number of samples analyzed was comprised of 15 F3-4 and 10 F0. Sequencing results of these samples detected a total of 777 miRNAs with normalized average count across all samples > 1, of which >19.7% showed dysregulated expression (fold-change ≥1.0, i.e., doubling or halving of expression). The differential expression analysis resulted in 75 miRNAs significant at adjusted p-value < 0.05, at varying level of expression. Results from hierarchical clustering analysis including all differentially expressed miRNAs are shown in Figure S1. Using a base mean ≥5.0, a Bonferroni-corrected P-value <0.05, and a 1-fold log2 (F3-4/F0) expression difference as a cut-off, 43 miRNAs showed statistically significant evidence for differential expression in liver samples from patients with NAFLD-fibrosis. Among these, 29 were down-regulated and 14 were up-regulated (Table S2). Among the down-regulated species, the ten most differentially expressed miRNAs were miR-219a, miR-373, miR-378c, miR-590, miR-3611, miR-376b, miR-186, miR-17, miR-1286, and miR-5699 (Table 2). Among the up-regulated species, the ten most differentially expressed miRNAs were miR-183, miR-31, miR-150, miR-182, miR-200a, miR-224, miR-92b, miR-3613, miR-708, and miR-766 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Top miRNAs showing significant downregulation in hepatic expression in NAFLD fibrosis

| Name | Base mean* | Fold change** | P-value | Adj. P-value*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa****-mir-219a-2 | 7.0 | −2.54 | 1.55E-04 | 4.68E-03 |

| hsa-mir-373 | 7.4 | −2.48 | 2.24E-05 | 1.08E-03 |

| hsa-mir-378c | 1252.7 | −2.33 | 3.68E-08 | 8.91E-06 |

| hsa-mir-590 | 5.5 | −2.32 | 5.64E-04 | 1.24E-02 |

| hsa-mir-3611 | 9.3 | −2.31 | 6.45E-04 | 1.30E-02 |

| hsa-mir-376b | 7.3 | −2.17 | 1.29E-03 | 2.02E-02 |

| hsa-mir-186 | 6.2 | −2.16 | 7.84E-04 | 1.39E-02 |

| hsa-mir-17 | 133.1 | −2.04 | 1.53E-06 | 1.12E-04 |

| hsa-mir-1286 | 5.4 | −1.98 | 3.30E-03 | 3.65E-02 |

| hsa-mir-5699 | 9.7 | −1.92 | 7.65E-04 | 1.39E-02 |

| hsa-mir-378i | 704.5 | −1.89 | 2.55E-07 | 4.63E-05 |

Base mean: average of normalized count values, taken over all samples

log2 ratio of miRNA (F3/4)/miRNA (F0)

Bonferroni-corrected P-value

hsa refers to Homo sapiens-specific miRNA per the standard miRNA nomenclature system

Table 3.

Top miRNAs showing significant upregulation in hepatic expression in NAFLD fibrosis

| Name | Base mean* | Fold change** | P-value | Adj. P-value*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-mir-183 | 27.1 | 1.99 | 4.23E-10 | 1.54E-07 |

| hsa-mir-31 | 35.1 | 1.77 | 1.10E-06 | 9.95E-05 |

| hsa-mir-150 | 4516.7 | 1.69 | 6.92E-07 | 8.96E-05 |

| hsa-mir-182 | 1130.5 | 1.68 | 5.69E-11 | 4.14E-08 |

| hsa-mir-200a | 12.3 | 1.66 | 1.46E-05 | 8.17E-04 |

| hsa-mir-224 | 189.0 | 1.62 | 7.40E-07 | 8.96E-05 |

| hsa-mir-92b | 268.5 | 1.30 | 4.00E-05 | 1.71E-03 |

| hsa-mir-3613 | 6.9 | 1.25 | 2.58E-03 | 3.11E-02 |

| hsa-mir-708 | 8.3 | 1.20 | 5.96E-04 | 1.28E-02 |

| hsa-mir-766 | 14.3 | 1.17 | 5.46E-04 | 1.24E-02 |

Base mean: average of normalized count values, taken over all samples

log2 ratio of miRNA (F3/4)/miRNA (F0)

Bonferroni-corrected P-value

Validation of selected miRNAs by RT-qPCR

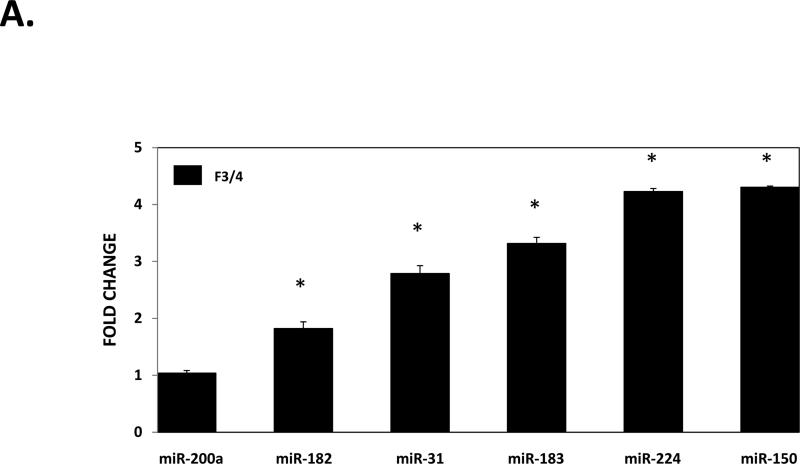

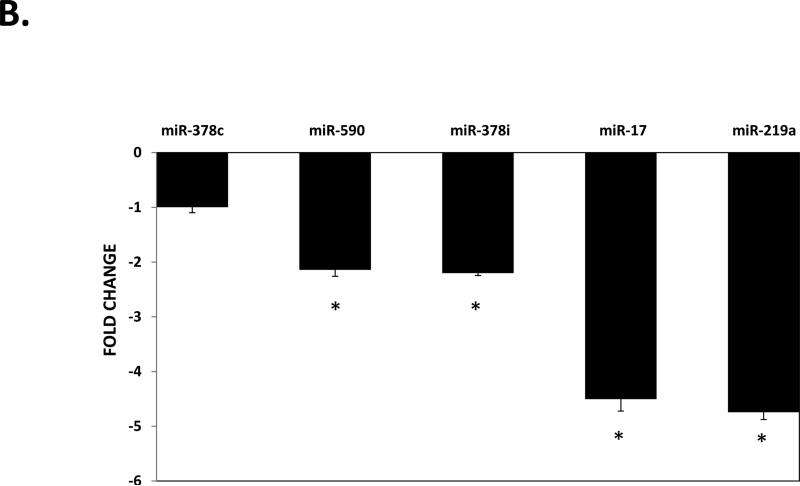

To validate the differential expression of hepatic miRNAs in NAFLD fibrosis identified by sequencing, we selected several miRNAs to analyze based on fold-change, statistical significance, and biological relevance for RT-qPCR analysis. These miRNAs included miR-182, miR-183, miR-150, miR-31, miR-224, miR-200a, miR-378c, miR-378i, miR-17, miR-373, miR-590, and miR-219a. As shown in Figure 1a, we confirmed up-regulation of miR-182, miR-183, miR-150, miR-31, and miR-224, but not miR-200a. We also confirmed significant down-regulation of miR-378i, miR-17, miR-590, and miR-219a, but not miR-378c and miR-373 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Validation of hepatic expression of individual miRNAs by RT-qPCR.

A) miRNAs showing up-regulated expression in fibrotic liver. B) miRNAs showing down-regulation in fibrotic liver. miRNAs were extracted from biopsied liver tissue from the same 30 individuals comprising the discovery cohort as described in the METHODS section. Relative quantification of each miRNA was performed by TaqMan RT-qPCR. Results are shown as F3-4 fold-change relative to F0 levels, which were set to a value of 1. All results represent averages from three independent experiments, normalized against miR-26a. Data are shown as means ± SD.

Functional enrichment analysis

We utilized functional enrichment analysis to identify pathways potentially affected by dysregulated hepatic miRNAs. The core analysis of the predicted targets resulted in 110 pathways with -log(adjusted p-value) > 1.36, out of which we highlighted nine due to their potential association with disease pathogenesis including hepatic fibrosis, hepatic stellate cell activation, TGFB signaling, and apoptosis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Functional enrichment analysis results

| Pathway | −log(adj-p-value) | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| EMT regulation | 9.60 | MAP2K4, RELA, ID2, FZD3, SMAD3, PIK3R1, HIF1A, FGFR3, TGFBR2, SMO, SMAD4, CTNNB1, FGF7, ETS1, SMAD2, FGF16, MAP2K7, PIK3C2A, ZEB1, MET, RHOA, ZEB2, FGFRL1, JAG1, NOTCH1, TCF7L2, MMP9, WNT5A |

| Apoptosis signaling | 8.50 | TP53, MAP2K4, RELA, MAP2K7, APAF1, PLCG1, IKBKE, BAX, FAS, BAK1, CASP6, CAPN8, PLCG2, TNFRSF1B, TNF, MAP4K4, CASP7, BCL2L11, FASLG |

| Hepatic fibrosis/hepatic stellate cell activation | 5.18 | RELA, SMAD2, CCR5, CTGF, SMAD3, IL6R, BAX, FAS, PDGFB, TGFBR2, MET, VEGFA, ACTA2, IGFBP3, IGF1R, SMAD4, CD14, ILIB, TNFRSF1B, TNF, MMP9, AGTR1, FASLG |

| TGFB signaling | 4.07 | TGFBR2, MAP2K4, SMAD2, JUN, RUNX2, SMAD3, ACVR1, SMAD4, BMPR2, BMP7, SMAD5, BMPR1B, SMAD1, ACVR1B |

| Hepatic cholestasis | 3.46 | MAP2K4, PRKACB, PPARA, RELA, MYD88, ADCY6, IKBKE, IL13, PRKC1, JUN, ILIRN, NR1I2, CD14, IL1B, TNFRSF1B, TNF, ESR1, IL11 |

| IGF-1 signaling | 2.74 | PRKACB, SOCS1, JUN, PRKC1, CTGF, FOXO1, PIK3C2A, PIK3R1, FOXO3, IGFBP3, IGF1R, CYR61, SOCS5 |

| T2D signaling | 2.00 | MAP2K4, SOCS1, RELA, MAP2K7, PIK3C2A, PIK3R1, IKBKE, CEBPB, MTOR, PRKC1, TNFRSF1B, TNF, SOCS5 |

| Growth hormone signaling | 1.98 | SOCS1, PRKC1, PIK3C2A, PLCG2, PIK3R1, IGF1R, IGFBP3, PLCG1, RPS6KA5, SOCS5 |

| ERK/MAPK signaling | 1.92 | PRKACB, ETS1, PIK3C2A, PPP2R2A, PIK3R1, ITGA2, PLCG1, ITGA5, RPS6KA5, MYC, TLN2, PRKC1, PPP2R4, PLCG2, CREB1, ATF4, ESR1 |

Expression changes of downstream targets of miR-182 in fibrotic liver

Because of the known role of miR-182 in mechanisms related to hepatocellular carcinoma [27-29], we sought to investigate this miRNA in NAFLD-related fibrosis by looking at relevant target genes. We used three algorithms (miRanda [23,24], miRWalk [25], and miRTarBase [26]) to identify potential mRNA targets of miR-182, and found FOXO3 and FBXW7, both of which have been implicated in hepatic metabolism [30,31]. We measured levels of both FOXO3 and FBXW7 in F0 and F3-4 samples and as shown in Figure 2a and 2b, we observed a significant decrease in both transcript and protein levels of FOXO3 (P=0.0001), respectively. In contrast, we did not find any significant differences in FBXW7 expression (Fig. 2c and 2d, respectively) between cases and controls.

Figure 2. Hepatic expression of FOXO3 (A) and FBXW7 (B) transcript and protein.

Total RNA and protein were extracted from the biopsied liver tissue from the same individuals comprising the discovery cohort as described in METHODS section. Relative quantification mRNA was performed by TaqMan RT-qPCR and normalized against ACTB. Protein concentrations were assessed via ELISA and are depicted as percentage of total soluble protein (TSP). Results represent averages from three independent experiments. Data are shown as means ± SD.

Discussion

It is now widely accepted that the dysregulation of miRNA expression or action contributes to the development of many different human diseases including certain cancers [6], neurological disorders [7], and heart disease [8]. In this study, we employed high throughput sequencing to identify differentially expressed hepatic miRNAs associated with NAFLD-related fibrosis. We observed evidence for differential expression of 43 hepatic miRNAs in biopsy-proven NAFLD fibrosis and confirmed dysregulation of ten of these, including miR-182, miR-183, miR-150, miR-31, miR-224, miR-378c, miR-378i, miR-17, miR-590, and miR-219a. To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply a high throughput sequencing approach to the investigation of hepatic miRNAs in NAFLD-related fibrosis.

Some of the present results corroborate findings of dysregulated levels of miRNA identified in other studies. In one study, hepatic levels of miR-200a and miR-224 were upregulated 1.25-fold and 1.35-fold, respectively in individuals with NASH [15]. Expression of miR-150 was dysregulated in visceral adipose tissue in NAFLD patients, although in this study, levels were decreased (−1.86-fold) in contrast to the results reported here [32]. This discrepancy may reflect effects of tissue-specific differential expression, although additional studies will be necessary to address this possibility. Hepatic levels of miR-224, miR-17-5p and miR-378 were also dysregulated in ob/ob mice [9]. Interestingly, the strongest replication was found with miR-182, which has been previously associated with hepatocellular carcinoma [27-29]. Dolganiuc et al [33] observed hepatic upregulation of miR-182, as well as its miR sibling, miR-183, in a mouse model of diet-induced NASH compared to control animals. In mice, miR-182, miR-183, and miR-96 are expressed from a unique primary transcript [34], which is highly conserved in humans and directly activated by sterol regulatory element binding protein-2 (SREBP-2) [30]. Conversely, miR-182 was shown to regulate SREBP expression through the direct inactivation of its target gene, Fbxw7, thereby contributing to a regulatory loop for intracellular lipid homeostasis [30]. However, when we investigated hepatic Fbxw7 levels, we did not observe significant differences in expression between fibrotic and non-fibrotic tissue, suggesting that other mechanisms may compensate for reduced expression of this gene.

We identified FOXO3 as a potential target gene of miR-182. Previous studies have shown that deletion of FOXO3 increases hepatic lipid secretion and causes hepatosteatosis [31]. Increased FOXO3 levels are associated with upregulation of the pro-apoptotic BH3-containing protein, PUMA, resulting in cholangiocyte injury through lipoapoptosis in NAFLD and NASH patients [35]. FOXO3 may also protect against other forms of liver disease [36,37] and regulate hepatic glucose metabolism [38]. While miR-182 is recognized as an important regulator of FOXO3 expression in skeletal muscle and lung cancer cells [39,40], a role for this miRNA/mRNA relationship has not been demonstrated in NAFLD-related fibrosis. We observed significant downregulation of FOXO3 transcript and protein levels in fibrotic compared to non-fibrotic liver (p>0.0001), suggesting a potential role for this gene in fibrogenesis. Additional studies, including validation of a direct interaction between miR-182 and FOXO3 and knockdown/overexpression experiments will be necessary to confirm this relationship.

The role of tissue-specific and circulating miRNAs in NAFLD has been explored in previous studies (Table 5). Cheung et al [15] profiled liver miRNA in 15 individuals with NASH and 15 individuals with normal liver histology and found that out of the 474 miRNAs represented on the array, only six showed differential expression between the two groups. Of these, up-regulation of miR-34a and miR-146b and down-regulation of miR-122 were confirmed using RT-PCR. However, in this study, miRNA levels were not associated with NASH severity, suggesting a role in biological processes not related to liver fibrosis. A similar analysis profiled miRNA expression in visceral adipose tissue of patients with NAFLD [32]. A total of 113 miRNAs were differentially expressed between groups, but only seven of these remained significant after correction for multiple testing. In an investigation of circulating serum miRNAs, Pirola et al [16] observed significantly upregulated levels of miR-122, miR-192, miR-19a and miR-19b, miR-125b, and miR-375 in patients with either simple steatosis or NASH. Levels of miR-122 and miR-192 showed the most dramatic changes in NASH patients versus controls.

Table 5.

Summary of miRNAs previously associated with NAFLD-related parameters

| Population | Phenotype | Method | Source | Major miRNAs identified | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian* | NASH | array | liver |

↑

miR-34a, miR-146b

↓ miR-122*** |

[15] |

| Caucasian* | NASH | array | adipose tissue | ↓ miR-132, miR-150, miR-433, miR-28-3p, miR-511, miR-517a, miR-671, miR-197, miR-99b | [32] |

| Unknown | NAFLD | qPCR | serum | ↑ miR-122, miR-34a, miR-16 | [42] |

| Chinese | NAFLD | RT-PCR | serum | ↑ miR-15b | [14] |

| Unknown | NAFLD | array | serum | ↑ miR-122, miR-192, miR-19a, miR-19b, miR-125b, miR-375 | [16] |

| Caucasian | NAFLD-fibrosis | NGS* | liver |

↑

miR-182, miR-183, miR-150, miR-224, miR-200a, miR-31

↓ miR-378c, miR-17, miR-373 |

Present study |

≥ 80% Caucasian

**whole genome next generation sequencing

bold font represents miRNAs identified in more than one study

As shown in Table 5, results from miRNA studies in NAFLD performed to date have been largely inconsistent. Lack of reproducibility among studies likely stems from a number of variables including differences in study design, clinical variability between cases and controls, methods of statistical evaluation, and experimental approaches. Each study used a different technology platform with a dissimilar representation of selected miRNAs, which presents significant difficulties for inter-study comparisons. For example, Pirola et al [16] used the MIHS 106Z PCR array, which interrogates 84 miRNAs. Of the twelve validated miRNAs in the present study, only four (miR-150, miR-224, miR-200a, and miR-17) were present on this array. The other studies were published several years ago, when far fewer miRNAs had yet been discovered, including many of the miRNAs identified in the present study. Differences in source miRNA may also contribute to poor reproducibility among studies since each of the studies published to date analyzed miRNA from different sources (i.e., liver, visceral adipose tissue, and serum). Like Cheung et al [15], we used liver-derived miRNA in our analyses. However, the lack of corroboration between studies is not surprising, given that, unlike the present study, the authors excluded patients with extreme fibrosis and cirrhosis and used normal, healthy individuals as controls. Overall, the present study differed from previous reports by implementing a high throughput, unbiased sequencing approach that did not rely on a pre-selected panel of miRNAs for interrogation, analyzing a carefully stratified study sample comprised of biopsy-proven NAFLD with or without fibrosis, and using human liver as the source for miRNA.

Despite the significance of these findings, we recognize that the present study has some limitations that are important to acknowledge. First, this study is comprised solely of obese females who are candidates for gastric bypass surgery and in whom the pathophysiology of hepatic fibrosis may be unique. However, we designed this study sample for two reasons: 1) obesity is a significant risk factor for worse liver-related outcomes in NAFLD [41], and 2) the value of obtaining liver tissue from individuals without clinical indication, which effectively removes bias toward clinically suspect liver disease. Despite these considerations, conclusions with regard to NAFLD-related fibrosis obtained from this group may not be readily relevant to other populations without additional validation.

Second, the sample size in the present study, while comparable to other reports [15,32], is still considered small, which may limit our ability to detect real differences in miRNA levels. For this reason, we consider this study an exploratory one and acknowledge that validation in a larger, independent dataset will be necessary to confirm our findings. In addition, we acknowledge that the stratification of the study sample into phenotypic extremes does not allow assessment of intermediate levels of peri-sinusoidal fibrosis (F1A and F1B) or portal fibrosis (F1C). We dichotomized our cohort into extreme histologic phenotypes to increase our power to identify clinically relevant differences in miRNA levels. Additional studies including individuals spanning the spectrum of NAFLD fibrosis will be critical to further validate these findings. We also note that the cross-sectional design does not allow associations with disease progression to be drawn. In the absence of serial liver biopsies in the present cohort, we were not able to utilize a prospective design. Assessment of miRNA levels in longitudinal biopsies will be necessary to determine the roles of specific candidates in disease progression.

Finally, the results reported here do not allow us to make specific conclusions about miRNAs and biological pathways. Additional studies, including those showing direct interactions between miRNAs and target genes, as well as functional consequences of miRNA effects on putative targets, will be necessary to confirm the role of specific miRNAs in liver fibrosis.

In summary, the results obtained in the current study provide evidence of differential levels of a number of hepatic miRNAs in NAFLD-related fibrosis. These data may help to yield new insights into the pathological mechanisms underlying the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis in NAFLD. Future investigations including validation in independent cohorts and functional characterization of miRNA gene targets and pathways will be important to extend these findings.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Differential hepatic miRNA expression in NAFLD patients with and without fibrosis. The heatmap shows all differentially expressed miRNAs at adjusted p-value < 0.05 in NAFLD patients with stage F3-4 fibrosis compared to NAFLD patients with no evidence of fibrosis (F0). Signal intensity was expressed as the log2 ratio between groups. Samples were grouped using hierarchical clustering based on similar expression profiles. Red, under-expression, white, no change, blue, overexpression.

Brief Commentary.

Background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a spectrum of conditions resulting from excessive accumulation of fat in hepatocytes not due to overconsumption of alcohol. Many NAFLD patients will also develop steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and/or cirrhosis, which are associated with increased liver-related morbidity and mortality. At present, the ability to predict which NAFLD patients are more likely to develop coincident inflammation and fibrosis and/or cirrhosis is limited by an incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis underlying progression to more severe manifestations of the disease.

Translational Significance

The findings reported here yield new insights into the pathological mechanisms underlying the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis in NAFLD.

Acknowledgements

The authors have read the journal's authorship agreement and the manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all authors. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grant DK091601 and the Translational Genomics Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors have read the journal's policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and have none to declare.

References

- 1.McCullough AJ. The clinical features, diagnosis and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:521–533. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafiq N, Bai C, Fang Y, Srishord M, McCullough A, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Saetrom P, Snove O, Jr., Rossi JJ. MicroRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16230–16235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808830105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alisi A, Da Sacco L, Bruscalupi G, Piemonte F, Panera N, et al. Mirnome analysis reveals novel molecular determinants in the pathogenesis of diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lab Invest. 2011;91:283–293. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin X, Chen YP, Kong M, Zheng L, Yang YD, et al. Transition from hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis: unique microRNA patterns and potential downstream functions and pathways. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:331–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn J, Lee H, Chung CH, Ha T. High fat diet induced downregulation of microRNA-467b increased lipoprotein lipase in hepatic steatosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang T, Liu C, Ye Z. Deep sequencing of small RNA repertoires in mice reveals metabolic disorders-associated hepatic miRNAs. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller AM, Gilchrist DS, Nijjar J, Araldi E, Ramirez CM, et al. MiR-155 has a protective role in the development of non-alcoholic hepatosteatosis in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pogribny IP, Starlard-Davenport A, Tryndyak VP, Han T, Ross SA, et al. Difference in expression of hepatic microRNAs miR-29c, miR-34a, miR-155, and miR-200b is associated with strain-specific susceptibility to dietary nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1437–1446. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian GP, Tang YY, He PP, Lv YC, Ouyang XP, et al. The effects of miR-467b on lipoprotein lipase (LPL) expression, pro-inflammatory cytokine, lipid levels and atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Zhou W, Hu W, Zhou L, Wang S, et al. Collagen/silk fibroin bi-template induced biomimetic bone-like substitutes. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;99:327–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Cheng X, Lu Z, Wang J, Chen H, et al. Upregulation of miR-15b in NAFLD models and in the serum of patients with fatty liver disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung O, Puri P, Eicken C, Contos MJ, Mirshahi F, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with altered hepatic MicroRNA expression. Hepatology. 2008;48:1810–1820. doi: 10.1002/hep.22569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirola CJ, Fernandez Gianotti T, Castano GO, Mallardi P, San Martino J, et al. Circulating microRNA signature in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: from serum non-coding RNAs to liver histology and disease pathogenesis. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood GC, Chu X, Manney C, Strodel W, Petrick A, et al. An electronic health record-enabled obesity database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiStefano JK, Kingsley C, Craig Wood G, Chu X, Argyropoulos G, et al. Genome-wide analysis of hepatic lipid content in extreme obesity. Acta Diabetol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0654-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood GC, Chu X, Manney C, Strodel W, Petrick A, et al. An electronic health record-enabled obesity database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedlander MR, Mackowiak SD, Li N, Chen W, Rajewsky N. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:37–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N. miRWalk--database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu SD, Lin FM, Wu WY, Liang C, Huang WC, et al. miRTarBase: a database curates experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D163–169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Ren R, Hu H, Tan C, Han M, et al. MiR-182 is up-regulated and targeting Cebpa in hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:17–29. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2014.01.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Li J, Shen J, Wang C, Yang L, et al. MicroRNA-182 downregulates metastasis suppressor 1 and contributes to metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang QH, Sun HM, Zheng RZ, Li YC, Zhang Q, et al. Meta-analysis of microRNA-183 family expression in human cancer studies comparing cancer tissues with noncancerous tissues. Gene. 2013;527:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon TI, Esquejo RM, Roqueta-Rivera M, Phelan PE, Moon YA, et al. An SREBP-responsive microRNA operon contributes to a regulatory loop for intracellular lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2013;18:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang K, Li L, Qi Y, Zhu X, Gan B, et al. Hepatic suppression of Foxo1 and Foxo3 causes hypoglycemia and hyperlipidemia in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:631–646. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estep M, Armistead D, Hossain N, Elarainy H, Goodman Z, et al. Differential expression of miRNAs in the visceral adipose tissue of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:487–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolganiuc A, Petrasek J, Kodys K, Catalano D, Mandrekar P, et al. MicroRNA expression profile in Lieber-DeCarli diet-induced alcoholic and methionine choline deficient diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis models in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1704–1710. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu S, Witmer PD, Lumayag S, Kovacs B, Valle D. MicroRNA (miRNA) transcriptome of mouse retina and identification of a sensory organ-specific miRNA cluster. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25053–25066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natarajan SK, Ingham SA, Mohr AM, Wehrkamp CJ, Ray A, et al. Saturated free fatty acids induce cholangiocyte lipoapoptosis. Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hep.27175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni HM, Du K, You M, Ding WX. Critical role of FoxO3a in alcohol-induced autophagy and hepatotoxicity. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1815–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tumurbaatar B, Tikhanovich I, Li Z, Ren J, Ralston R, et al. Hepatitis C and alcohol exacerbate liver injury by suppression of FOXO3. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1803–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong X, Tao R, DePinho RA, Dong XC. Deletion of hepatic FoxO1/3/4 genes in mice significantly impacts on glucose metabolism through downregulation of gluconeogenesis and upregulation of glycolysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hudson MB, Rahnert JA, Zheng B, Woodworth-Hobbs ME, Franch HA, et al. miR-182 attenuates atrophy-related gene expression by targeting FoxO3 in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:C314–319. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00395.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang WB, Chen PH, Hsu Ts, Fu TF, Su WC, et al. Sp1-mediated microRNA-182 expression regulates lung cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2014;5:740–753. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiang DJ, Pritchard MT, Nagy LE. Obesity, diabetes mellitus, and liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G697–702. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00426.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cermelli S, Ruggieri A, Marrero JA, Ioannou GN, Beretta L. Circulating microRNAs in patients with chronic hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Differential hepatic miRNA expression in NAFLD patients with and without fibrosis. The heatmap shows all differentially expressed miRNAs at adjusted p-value < 0.05 in NAFLD patients with stage F3-4 fibrosis compared to NAFLD patients with no evidence of fibrosis (F0). Signal intensity was expressed as the log2 ratio between groups. Samples were grouped using hierarchical clustering based on similar expression profiles. Red, under-expression, white, no change, blue, overexpression.