Abstract

Purpose: To evaluate the effectiveness of early and delayed motion in rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using a meta-analysis from randomized controlled trials. Materials and Methods: Electronic searches of the CENTRAL, PUBMED, and EMBASE were used to identify randomized controlled trials that evaluated the effectiveness and safety of early and delayed motion for rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias. Results: Four randomized controlled trials involving a total of 348 shoulders were included. Of these, two were rated as high quality and two were rated as moderate quality. No significant publication bias was detected by Egger’s test and sensitivity analysis demonstrates a statistically robust result. Our meta-analysis indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a significantly greater recovery of external rotation from pre-operation to 3, 6, and 12 months post-operation (P < 0.05) and forward elevation ability from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation (P < 0.05), as compared to when motion was delayed. However, early motion resulted in non-significant excess (P > 0.05) in the rate of recurrence, compared to delayed motion. In addition, there were statistically higher rating scale of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores at 12 months post-operation (P < 0.05) and healing rates (P < 0.05) with delayed motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, compared with early motion. Conclusion: Our meta-analysis included data from randomized controlled trials and demonstrated that delayed motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in higher healing rates and ASES scores than early motion. Alternatively, early motion increased range of motion (ROM) recovery, but also increased the rate of recurrence compared to delayed motion.

Keywords: Rehabilitation protocol, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, early motion, delayed motion, meta-analysis

Introduction

Rotator cuff tears are common tendon injuries and are typically caused by traumatic injury or age-associated degeneration; approximately 54% of adults older than 60 have a partial or complete rotator cuff tear, as compared with only 4% of those between the ages of 40 to 60 [1]. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair is a surgical treatment and has become more commonly used because of the potential benefits of smaller incisions, less trauma to the deltoid, ability to address concomitant disorders, better patient acceptance, and less postoperative pain [2,3]. Although an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair appears to be a relatively minor procedure, postsurgical rehabilitation is long and critical for the long-term repair of the repaired tissue [4]. Physical rehabilitation has conventionally involved a delayed motion protocol, with a 4- to 6-week period of immobilization [5]. However, many surgeons have started to implement aggressive rehabilitation with an early motion in order to prevent postoperative stiffness [6]. Several studies comparing the efficacy of early passive motion and immobilization was recently published [7-9], but the many outcomes of the meta-analysis resulted in high heterogeneity, nor did the authors report several significant outcomes and compare the development of the range of motion (ROM) between two methods.

The meta-analysis reported here was conducted to systematically review the randomized controlled rehabilitation trials of following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Our objective was to compare the effectiveness of early and delayed motion for rehabilitation.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and literature search

We searched the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, Issue 3 of 12, Mar 2015), PUBMED (1980 to Apr 2015), and EMBASE (1980 to Apr 2015) databases to identify all studies that discussed the effectiveness of early motion and delayed motion for rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair based on the following criteria: (rotator cuff tear OR rotator cuff injury) AND (surgery OR treatment OR therapy OR complications OR adverse effect) AND (rehabilitation OR early motion OR delayed motion) AND (randomized controlled trial); (“Rotator Cuff/injuries” [Mesh] OR “Rotator Cuff/surgery” [Mesh] OR “Rotator Cuff/therapy” [Mesh]) AND Randomized Controlled Trial [ptyp]. The inclusion criteria were: (1) target population: patients with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair; (2) intervention: early motion with rehabilitation exercises immediately following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and delayed motion with rehabilitation exercises 3 to 6 weeks after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair; (3) methodological criteria: randomized controlled trials that compared early motion with delayed motion and reported on the effectiveness of both procedures. The exclusion criteria were: (1) target population: patients with open rotator cuff repair and other mini-open techniques; (2) intervention: delayed motion with rehabilitation exercises at less than 3 weeks or more than 6 weeks after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair; (3) methodological criteria: case-control study, case report, and cohort study.

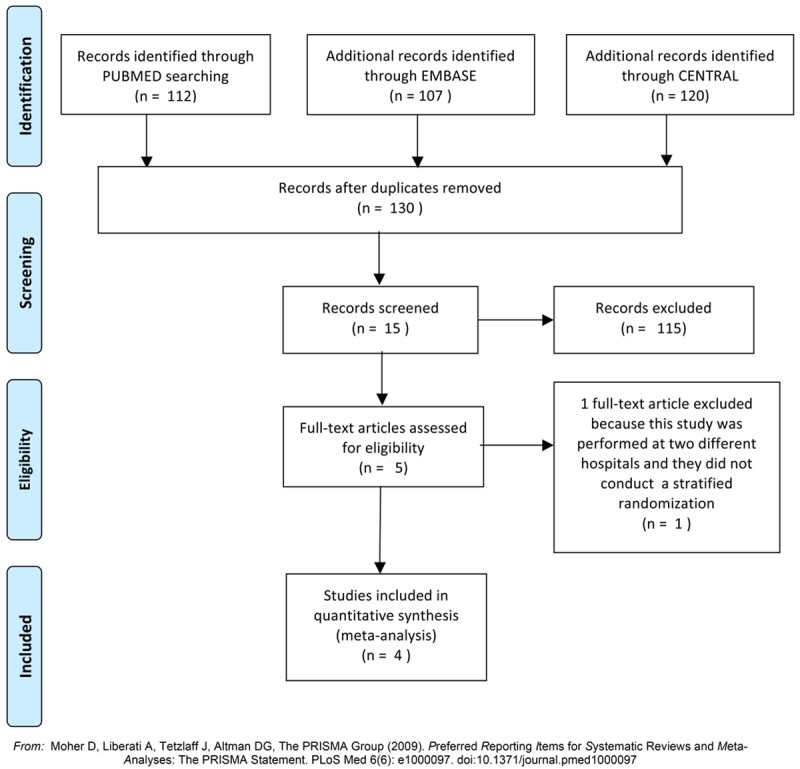

The search strategy retrieved: 120 studies from CENTRAL, 112 studies from PUBMED, and 107 studies from EMBASE. Two separate reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of these references, and 5 studies [10-14] were identified for further analysis. One study [13] was excluded because it was performed at two different hospitals and they did not perform a stratified randomization, which may have caused significant bias regarding the results of the study. The remaining four randomized trials were deemed to be relevant and were included in this meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the inclusion selection in the meta-analysis.

Outcome assessment

The primary outcomes measured were: ROM and rating scale of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES). For ROM, both the development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 and 12 months postoperatively and the development of external rotation pre-operation to 3, 6, and 12 months post-operation were included. The secondary outcomes measured included, external rotation strength at 12 months, healing rate, and rate of recurrence.

For each trial, we gathered data on the type of study, sample size, interventions, and length of follow-up. For the randomized controlled trials, we gathered data on the randomization process, allocation concealment process, blinding, selective reporting, and intention-to-treat analysis. In addition, the following clinical data were also extracted, if available: information on the development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 and 12 months post-operation, the development of external rotation from pre-operation to 3, 6, and 12 months post-operation, external rotation strength at 12 months, healing rate, and rate of recurrence. Two researchers extracted data independently according to pre-specified selection criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [15] was used to assess the quality of the randomized controlled trials. Briefly, the quality of the studies were assessed using the following criteria: 1) randomization sequence generation: assessment of selection bias; 2) allocation concealment: assessment of selection bias; 3) level of blinding (blinding of participants and blinding of outcome assessment): assessment of performance bias and detection bias; 4) incomplete outcome data: assessment of attrition bias; and 5) selective reporting: assessment of reporting bias [15].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager, version 5.2 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2012) and Stata, version 12.0. In each study, the relative risk (RR) was calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Moreover, the treatment effects for continuous outcomes included the mean differences (MD) for studies with comparable outcome measures and standardized mean differences (SMD) for data from disparate outcome measures; both used a 95% confidence interval (CI) [15]. Heterogeneity was assessed via visual inspection of the forest plot and by chi-square tests and I-square tests. Significance values less than 0.10 for chi-square tests or more than 50% for I-square tests were interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity. The I-square was used to estimate total variation across studies. When there was no statistical evidence of heterogeneity, a fixed effect model was applied; if heterogeneous, a random effect model was chosen [15]. Egger’s linear regression test [16] were used to detect publication bias. Significance levels of less than 0.05 for each test were interpreted as evidence of publication bias [16]. In order to assess the reliability of the results, sensitivity analysis was performed by omitting one study in each turn.

Results

Characteristics and qualities of included studies

Four trials that evaluated the combined treatment of 348 shoulders were included in the analysis. Table 1 presents the study characteristics (study type, sample size, interventions, and length of follow-up). Of the four randomized controlled trials [10-12,14], analysis using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool indicated that two [11,12] used adequate randomization and three [11,12,14] used adequate allocation concealment (Table 2). Two studies [11,12] reported outcome assessment blinding; however, patient blinding was not feasible in this study design. Three studies [10,12,14] lacked follow-up reporting. None of the included studies utilized the intention to treat (ITT) analysis. All of the included randomized controlled trials were free of selective reporting.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies Comparing Early motion Versus Delayed motion For the Rehabilitation after Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

| Author group | Country | Study type | Intervention | Sample size patient/shoulder | Length of follow-up (months) | For analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arndt 2012 | France | RCT | Early vs Delayed | 92/92 | 16 | (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (8), (9) |

| Cuff 2012 | USA | RCT | Early vs Delayed | 68/68 | 12 | (1), (2), (6), (8) |

| Keener 2014 | USA | RCT | Early vs Delayed | 114/114 | 24 | (6), (7), (8), (9) |

| Lee 2012 | South Korea | RCT | Early vs Delayed | 64/64 | 12 | (3), (4), (5), (7), (8), (9) |

For analysis: (1) Development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation; (2) Development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation; (3) Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 3 months post-operation; (4) Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation; (5) Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation; (6) ASES score at 12 months post-operation; (7) External rotation strength at 12 months post-operation; (8) healing rate; (9) the rate of recurrence.

Table 2.

Quality Assessment of Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Early motion Versus Delayed motion For the Rehabilitation after Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair using Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias

| Author group | Adequate randomization | Adequate allocation concealment | Adequate patient blinding | Adequate outcome assessment blinding | Loss-to follow-up reporting | Intention to treat analysis | Free of selecting report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arndt 2012 | Unclear | Unclear | N/A | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Cuff 2012 | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | Unclear | Y |

| Keener 2014 | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Lee 2012 | Unclear | Y | N/A | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y |

Y, Low risk of bias; N, High risk of bias; Unclear, Unclear risk of bias; N/A, not applicable.

Primary outcomes

ROM

Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 3 months post-operation

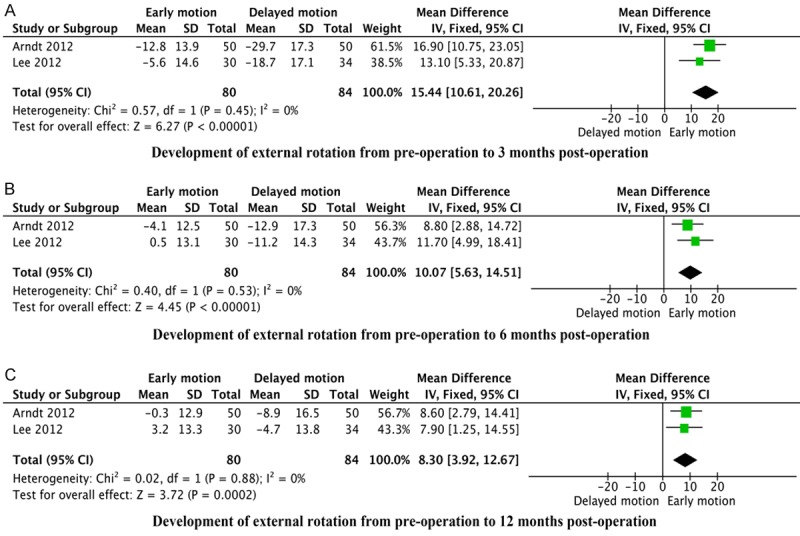

Data pooled from two studies [10,14] (n = 164 shoulders) indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in significantly better recovery of external rotation from pre-operation to 3 months post-operation, as compared to delayed motion (15.44°, 95% CI: 10.61 to 20.26, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing the development of external rotation from pre-operation to (A) 3 months, (B) 6 months, and (C) 12 months post-operation of early motion and delayed motion for rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. SD, standard deviation.

Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation

Data pooled from two studies [10,14] (n = 164 shoulders) indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in significantly better recovery of external rotation at from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation, compared to delayed motion (10.07°, 95% CI: 5.63 to 14.51, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%; Figure 2B).

Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 12 months postoperation

Data pooled from two studies [10,14] (n = 164 shoulders) indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in significantly better recovery of external rotation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation, compared to delayed motion (8.30°, 95% CI: 3.92 to 12.67, P = 0.0002, I2 = 0%; Figure 2C).

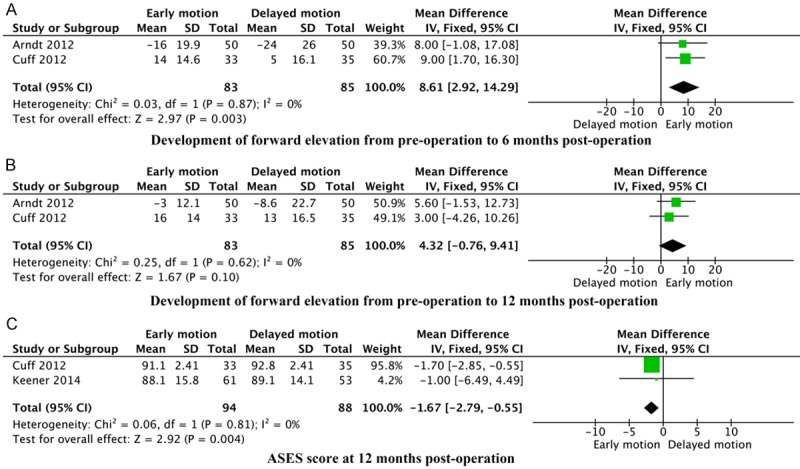

Development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation

Data pooled from two studies [10,11] (n = 168 shoulders), indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in significantly better recovery of shoulder forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 months postoperatively than delayed motion (8.61°, 95% CI: 2.92 to 14.29, P = 0.003, I2 = 0%; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing the development of forward elevation from pre-operation to (A) 6 months, (B) 12 months post-operation and ASES scores at 12 months (C) of early motion and delayed motion for rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. SD, standard deviation.

Development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation

Data pooled from two studies [10,11] (n = 168 shoulders) indicated that there was no statistical difference between early motion and delayed motion following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in the development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation (4.32°, 95% CI: -0.76 to 9.41, P = 0.10, I2 = 0%; Figure 3B).

ASES score at 12 months post-operation

Data pooled from two studies [11,12] (n = 182 shoulders) indicated that delayed motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a significantly higher ASES score at 12 months post-operation, compared to early motion (-1.67, 95% CI: -2.79 to -0.55, P = 0.004, I2 = 0%; Figure 3C).

Secondary outcomes

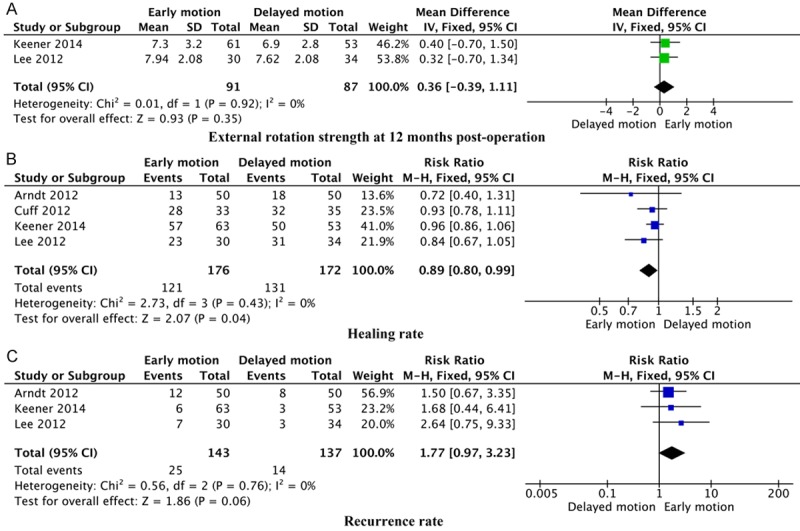

External rotation strength at 12 months post-operation

Data pooled from two studies [12,14] (n = 178 shoulders) revealed no statistical difference between early motion and delayed motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in external rotation strength at 12 months post-operation (0.36, 95% CI: -0.39 to 1.11, P = 0.35, I2 = 0%; Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Forest plots showing the external rotation strength at 12 months (A), healing rate (B) and recurrence rate (C) of early motion and delayed motion for rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

Healing rate

Data pooled from all four trials [10-12,14] (n = 348 shoulders) indicated that delayed motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a significantly higher rate of healing than early motion (RR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.80 to 0.99, P = 0.04, I2 = 0%; Figure 4B).

Recurrence rate

Data pooled from three trials [10,12,14] (n = 280 shoulders) suggested that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a higher rate of recurrence, compared to delayed motion (RR: 1.77, 95% CI: 0.97 to 3.23, P = 0.06, I2 = 0%); however, the excess was not statistically significant (Figure 4C).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

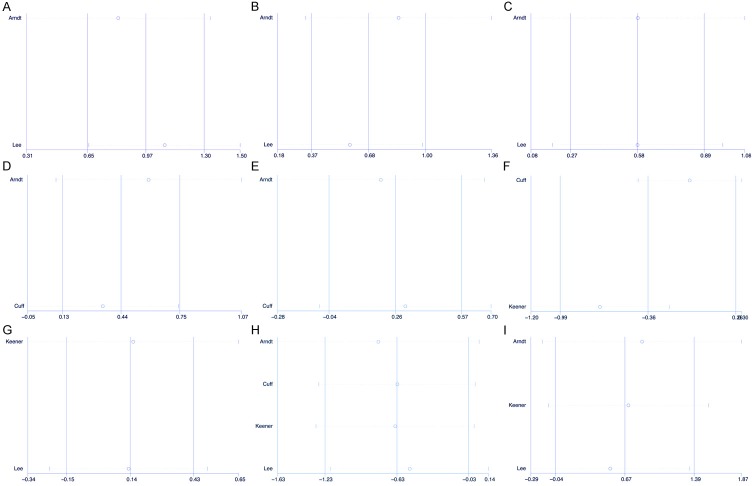

Because of the small number of trials in some analyses, Egger’s linear regression test were only performed to assess the publication bias in the analyses of healing rate and recurrence rate. Results showed that this meta-analysis had no significant publication biases (Table 3). Sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the influence of each individual study on the pooled SMD or OR by omitting of individual studies. The analysis results indicated that no individual studies significantly affected the pooled SMD or OR (Figure 5), demonstrating a statistically robust result.

Table 3.

Egger’s linear regression test for the available analysis

| Analysis | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healing rate | -.9886062 | .8427882 | -1.17 | 0.362 | -4.614831 | 2.637619 |

| Recurrence rate | 1.551915 | 1.728458 | 0.90 | 0.534 | -20.41022 | 23.51405 |

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of pooled SMD or OR coefficients on each analysis comparing early motion and delayed motion for rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. A. Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 3 months post-operation; B. Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation; C. Development of external rotation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation; D. Development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation; E. Development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation; F. ASES score at 12 months post-operation; G. External rotation strength at 12 months post-operation; H. Healing rate; I. Recurrence rate.

Discussion

This meta-analysis included data from four randomized controlled trials involving a total of 348 shoulders with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Our meta-analysis indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a significantly better recovery of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation and external rotation from pre-operation to 3, 6, and 12 months post-operation compared to delayed motion. However, early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a non-significant excess in the rate of recurrence, as compared to delayed motion. Moreover, there were statistically higher ASES scores at 12 months post-operation and healing rates with delayed motion than with early motion. Our meta-analysis also indicated that there were no statistical differences between the two procedures in the development of forward elevation from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation and external rotation strength at 12 months post-operation.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, the number of shoulders utilized in our study was relatively low because of we included only randomized controlled trials in order to ensure the significance of our conclusions. Second, the lack of any treatment-provider blinded studies may have introduced detection bias, in which the assessors potentially preferentially attributed a level of injury occurrence to the control group. Third, the included studies did not provide sufficient outcome data, for example, the standard deviation, so we figured out the insufficient outcome data through some statistical methods based on the data which the included studies provided. Finally, the results of an observational study can be influenced by unmeasured confounders such as physical activity, infective factors, and environment. We were unable to evaluate these confounders in our meta-analysis.

ROM is important for evaluating the function of a shoulder after surgery. Riboh [9] found that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in a better recovery of ROM than delayed motion, but this data also exhibited a high level of heterogeneity. In our meta-analysis, we found that the high heterogeneity of ROM in Riboh’s study resulted in an inconsistent baseline. As such, we measured the development of ROM comparing pre-operation to post-operation to evaluate the two methods. Results indicated that early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in significantly better recovery of forward elevation from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation and external rotation from pre-operation to 3, 6, and 12 months post-operation, as compared to delayed motion.

Koo [6] previously reported that early motion may increase the chance of a recurrent cuff tear. Alternatively, Riboh [9] did not see a difference between the two techniques in regard to tear rate. Our meta-analysis was conducted with more strict inclusion criteria and found that early motion did not result in a significant change in the rate of recurrence compared to delayed motion. We also found that delayed motion significantly increased the healing rate, as compared to early motion.

ASES score is a standardized form for assessing shoulder recovery, designed by The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons, that contains scales for pain and instability and an activities of daily living questionnaire [17]. In our meta-analysis, we identified statistically higher ASES scores 12 months post-operation with delayed motion, as compared with early motion. Our meta-analysis also indicated a lack in significance between the two procedures in both the development of forward elevation capabilities from pre-operation to 12 months post-operation and in external rotation strength at 12 months post-operation.

Nowadays, many surgeons encourage a rehabilitation protocol following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair that includes early motion because early motion often increases ROM recovery compared to delayed motion [5], as indicated by our data. However, delayed motion resulted in a lower rate of recurrence, higher rate of healing, and higher ASES scores than early motion. A lack of ROM is a complication that is much easier to overcome than recurrent cuff tears [6]. As such, we recognize that we should avoid starting rehabilitation too early after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in order to initiate healing and reduce the rate of recurrence.

Conclusion

In summary, our meta-analysis included data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating that delayed motion following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair resulted in both increased healing rates and ASES scores, as compared to early motion. Moreover, early motion resulted in better ROM recovery, but had a higher rate of recurrence than delayed motion.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bartolozzi A, Andreychik D, Ahmad S. Determinants of outcome in the treatment of rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;308:90–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gartsman GM. Arthroscopic acromioplasty for lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:169–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy HJ, Uribe JW, Delaney LG. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(90)90099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fermont AJ, Wolterbeek N, Wessel RN, Baeyens JP, de Bie RA. Prognostic factors for successful recovery after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic literature review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44:153–163. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2014.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross D, Maerz T, Lynch J, Norris S, Baker K, Anderson K. Rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a review of current literature. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:1–9. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-01-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koo SS, Burkhart SS. Rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan K, MacDermid JC, Hoppe DJ, Ayeni OR, Bhandari M, Foote CJ, Athwal GS. Delayed versus early motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1631–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang KV, Hung CY, Han DS, Chen WS, Wang TG, Chien KL. Early Versus Delayed Passive Range of Motion Exercise for Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1265–1273. doi: 10.1177/0363546514544698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riboh JC, Garrigues GE. Early Passive Motion Versus Immobilization After Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:997–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arndt J, Clavert P, Mielcarek P, Bouchaib J, Meyer N, Kempf JF. Immediate passive motion versus immobilization after endoscopic supraspinatus tendon repair: a prospective randomized study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:1. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Prospective randomized study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using an early versus delayed postoperative physical therapy protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keener JD, Galatz LM, Stobbs-Cucchi G, Patton R, Yamaguchi K. Rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective randomized trial of immobilization compared with early motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:11–19. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YS, Chung SW, Kim JY, Ok JH, Park I, Oh JH. Is early passive motion exercise necessary after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair? Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:815–821. doi: 10.1177/0363546511434287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 16.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, Friedman RJ, Gartsman GM, Gristina AG, Iannotti JP, Mow VC, Sidles JA, Zuckerman JD. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]