Abstract

Aim: There have been many reports on the reduction of liver disease with green tea consumption. This study aims to evaluate the body of evidence related to green tea consumption on the risk of liver disease and determine the effectiveness. Methods: Electronic searches were conducted in PubMed, CNKI, Wanfang and Weipu databases. Statistical analysis was performed using the software Revman 5.2 and Stata 12.0. Results: Meta-analysis revealed that among green tea drinkers, there was a significant reduction in the risk of liver disease (RR=0.68, 95% CI=0.56-0.82, P=0.000). This trend extends to a broad spectrum of liver conditions including hepatocellular carcinoma (RR=0.74, 95% CI=0.56-0.97, P=0.027), liver steatosis (RR=0.65, 95% CI=0.44-0.98, P=0.039), hepatitis (RR=0.57, 95% CI=0.45-0.73, P=0.000), liver cirrhosis (RR=0.56, 95% CI=0.31-1.01, P=0.053) and chronic liver disease (RR=0.49, 95% CI=0.29-0.82, P=0.007). This trend is also observed regardless of the race of the individual concerned where the Asian, American and European subgroups all demonstrated a reduced risk of liver disease. Conclusions: Green tea intake reduces the risk of liver disease. However, more long term randomized clinical trials are needed to comprehensively evaluate the health benefits of green tea.

Keywords: Green tea, liver disease, risk, meta-analysis

Introduction

The liver is one of the key metabolic organs in the organ involved in the synthesis and degradation of key biological molecules such as carbohydrate, protein and lipids among others. In recent decades, we have also seen a growing disease burden from liver diseases such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), fatty liver, and liver cirrhosis. Notably, primary hepatic malignancies, of which HCC is the most prevalent, is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths and the sixth most common cancer worldwide [1]. This is especially so in China where 44% of all such cases occurs in China, more so than in any other country [2].

There are many risk factors for liver diseases and many of these risk factors are common in china. For example, hepatitis B, which is common in China, is a significant risk factor for HCC [3]. On the other hand, obesity and extensive consumption of fatty foods are also shown to have a strong correlation with fatty liver [4].

With the prevalence of liver disease in China, the population has demonstrated strong health seeking behavior in trying to consume protective food products that will reduce their long-term risk for liver disease. Green tea is one of such food products that has been purported to have a certain degree of health benefits.

Green tea originated from China and South-East Asia thousands of years ago and has grown to become one of the most popular beverages worldwide [5]. While originally sought after for its fragrance and taste, its possible health benefits has gained great attention in recent years. Recent studies have shown that green tea has a certain degree of both preventive and therapeutic effects on liver disease. Studies have shown that green tea can help in the regulation of lipid metabolism, which reduces the accumulation of lipids in the liver. Studies have also shown that green tea contains a large amount of polyphenolic antioxidants that can offer a protective effect against malignant change [6]. The evidence for the health effects for green tea however have been predominantly focused on animals with limited human based studies to date. This study aims to evaluate the complete body of evidence on green tea so as to offer a comprehensive analysis of the effect of green tea on liver disease.

Methods

Literature-search strategy

A systematic search of literature was performed to investigate the associations between green tea consumption and liver disease. There was no restriction on the region where the study was conducted but the language was limited to Chinese and English. PubMed, CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), Wanfang and Weipu databases were used (the last search was performed on September 20th, 2014). Two groups of key words were combined to carry out a comprehensive search strategy in [Title/Abstract]: “-green tea OR Catechin OR Gallocatechin OR Epicatechin OR Epigallo catechin OREGC OR EGCG OREC OR ECG OR EGCg OR polyphenol” and “liver disease OR fatty liver disease OR NAFLD OR AFLD OR NASH OR hepaticsteatosis OR liver cancer OR hepatocellular carcinoma ORHCC OR PLC OR hepatitis OR cirrhosis” The Related Articles function was also used to broaden the search, and the computer search was supplemented with manual searches of references lists of all retrieved studies, review articles and conference abstracts.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All available studies including prospective, retrospective and cross-sectional studies that involved assessment of the extent of green tea were included. The following exclusion criteria were used: (a) animal experimental studies, (b) studies with object numbers not presented, (c) case reports, reviews, letters to the editor, editorialsor conference abstracts.

Data extraction and outcomes of interest

Two reviewers (Han and Song) independently extracted the data and reached a consensus on all items. Any disagreement was resolved by consulting the adjudicating senior author (Yin and Yang). The following information was extracted from each study: author, publication year, region, study type, outcomes and object number.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using RevMan 5.2 and Stata 12.0. The strength of the association green tea consumption and liver disease risk was measured by RRs and 95% CI. The statistical significance of summary RR was determined with the Z-test. The heterogeneity was assessed by a chi-square test and quantified using I2 statistic, and it was considered statistical significant at P<0.10. The pooled RR was analyzed using a random-effects model. Publication bias was analyzed by the Begg’s test and quantified using Egger’s test for statistical assessment. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequentially deleting a single study each time in an attempt to identify the potential influence of the individual data set to the pooled RRs.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

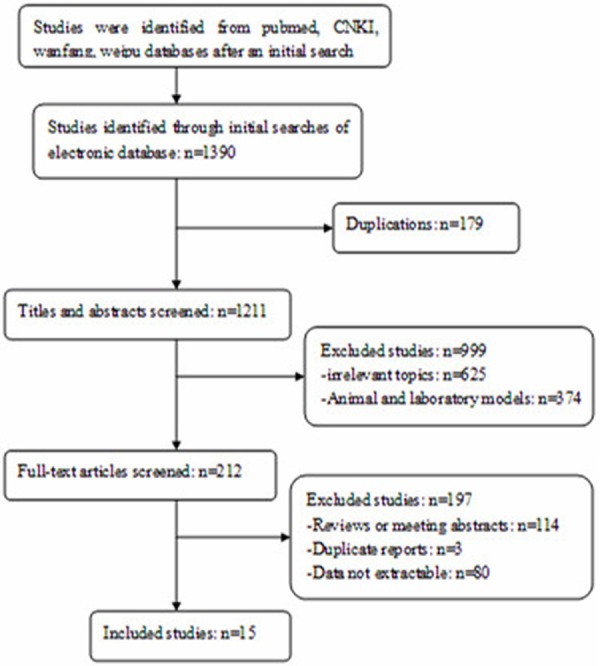

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. A total of 1390 results were identified after an initial search from the PubMed, CNKI, Wanfang and Weipu databases. The authors then manually screened through the titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant studies, reviews and duplicated results. Finally, a total of 15 studies were identified for meta-analysis and there were two researches including in one study [7-21].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies identified, included and excluded.

The included studies are shown in Table 1. Among the included studies, there were nine prospective cohort studies, three retrospective studies and four cross-sectional studies. Of these studies, nine focused on HCC, four focused on fatty liver, there were one study focusing on each of liver cirrhosis, hepatitis and chronic liver disease. Twelve of these studies were conducted in China, one in Japan, one in USA and one in Europe.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Region | Year | Study type | Objects no. | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| DT (E/T)* | NDT (E/T)* | |||||

| Gao S et al | China | 2011 | Prospective cohort | 147/63598 | 165/72827 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Mu LN et al | China | 2003 | Retrospective | 73/393 | 111/485 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Pan LY et al | China | 2008 | Retrospective | 24/110 | 60/110 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Sarah et al | China | 2012 | Prospective cohort | 27/18083 | 106/49140 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Shen HB et al | China | 1996 | Cross-sectional | 53/44148 | 153/62314 | Hepatocellularcarcinoma |

| Zhang ZQ et al | China | 1995 | Prospective cohort | 12/3474 | 29/2732 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Xu YC et al | China | 1998 | Prospective cohort | 12/80 | 11/78 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Nagano et al | Japan | 2001 | Prospective cohort | 58/5415 | 230/30910 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Bamia et al | Europe | 2014 | Prospective cohort | 114/297824 | 85/153097 | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Li L et al | China | 2001 | Retrospective | 95/409 | 56/248 | Fatty liver disease |

| Xia PJ et al | China | 2005 | Cross-sectional | 103/484 | 201/360 | Fatty liver disease |

| Xiao JP et al | China | 2002 | Cross-sectional | 16/175 | 33/145 | Fatty liver disease |

| Mu D et al | China | 1997 | Prospective cohort | 29/73 | 67/111 | Fatty liver disease |

| Yuan YBa et al | China | 2005 | Prospective cohort | 77/4295 | 269/8466 | Hepatitis |

| Yuan YBb et al | China | 2005 | Prospective cohort | 14/715 | 49/1379 | Liver cirrhosis |

| Ruhl CE et al | USA | 2005 | Cross-sectional | 18/1627 | 65/2844 | Chronic liver disease |

T=total; DT=drinking tea; NDT=not drinking tea.

Combined analysis

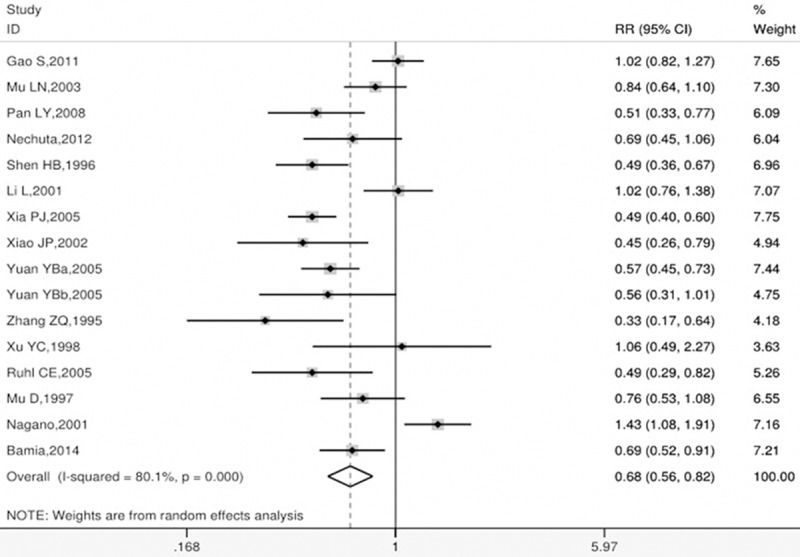

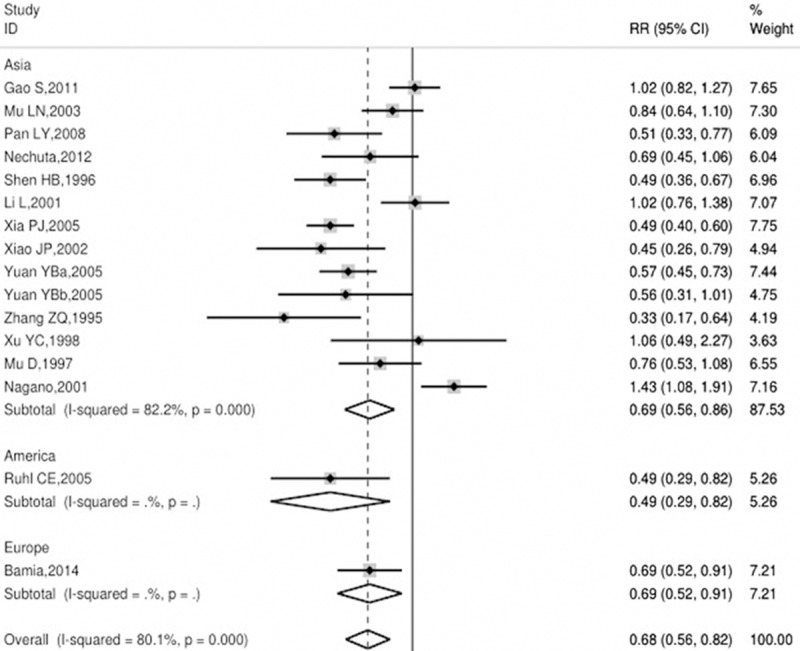

The pooled data yielded 440903 regular green tea drinking cases and 385246 irregular green tea drinking cases from 15 studies. A meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction in the incidence of liver diseases favoring green tea (RR=0.68, 95% CI=0.56-0.82, P=0.000). The results of meta-analysis are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis for the association between green tea intake and liver disease.

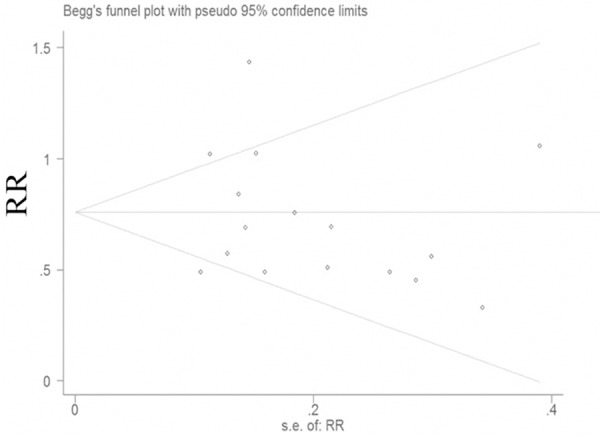

Because of the noted heterogeneity between the fifteen included studies (I2=80.1%), a random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled risk estimator. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot. The shape of the funnel plots seemed symmetrical suggesting no absence of publication bias (Figure 3). The Egger’s test was performed to provide statistical evidence of funnel plot symmetry (t=-0.65, P=0.526). The results indicated a lack of publication bias. In order to assess the stability of the results of the current meta-analysis, we performed a one-study removed sensitivity analysis. Statistically similar results were obtained after sequentially excluding each study, suggesting the stability of our meta-analysis in general.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot.

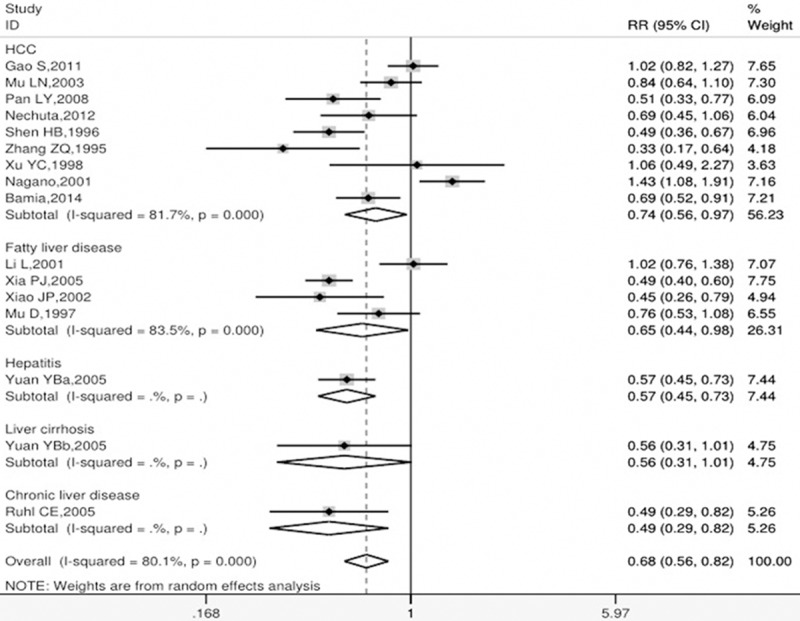

In the subgroup analyses by liver disease, HCC (RR=0.74, 95% CI=0.56–0.97, P=0.027), fatty liver disease (RR=0.65, 95% CI=0.44-0.98, P=0.039), hepatitis (RR=0.57, 95% CI=0.45-0.73, P=0.000), chronic liver disease (RR=0.49, 95% CI=0.29-0.82, P=0.007) all showed a significant reduction in incidence in the regular green tea drinking group (Figure 4). There was no significant difference for liver cirrhosis (RR=0.56, 95% CI=0.31-1.01, P=0.053). Publication bias of HCC group and fatty liver disease group was assessed by with funnel plot. The shape the funnel plots of was symmetric. The results indicated no presence of publication bias. We performed a one-study removed sensitivity analysis to assess the stability of the results of HCC group and fatty liver disease group’s subgroups meta-analysis. Statistically similar results were obtained after sequentially excluding each study, suggesting the stability of each meta-analysis in general.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis for subgroup by liver disease.

The authors then performed a subgroup analysis based on the region of the study. In all 3 subgroups, namely the Asian (RR=0.69, 95% CI=0.56-0.86, P=0.001), European (RR=0.69, 95% CI=0.52-0.91, P=0.009) and American (RR=0.49, 95% CI=0.29-0.82, P=0.007) studies (Figure 5), there was a significant reduction in incidence of liver disease upon regular consumption of green tea. Publication bias of Asian group was assessed with funnel plot.The shape the funnel plots of was symmetric. The results indicated no presence of publication bias. We performed a one-study removed sensitivity analysis to assess the stability of the results of Asian subgroup meta-analysis. Statistically similar results were obtained after sequentially excluding each study, suggesting the stability of each meta-analysis.

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis for subgroup by region.

Discussion

There has been an increasing recognition of the health benefits of green tea in recent years. Many studies have shown that the high levels of catechin, especially catechin (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), could have biological effects such as antioxidative, antiviral, anticarcinogenic, antimutagenic, anticancer, anti-inflammation, anti-obesity and hypolipidaemic effects [22]. The biological actions of such molecules have been studied in numerous animal studies and their effect on human health is corroborated by the several human studies since.

This meta-analysis evaluated the association between green tea drinking and liver diseases based on all published studies. We concluded that there is a significant protective effect of green tea drinking on liver diseases. Specifically, green tea intake is associated with decreased risk of HCC, fatty liver disease, hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and chronic disease. We investigated all methodological issues for the present meta-analysis. No publication bias was detected. The sensitivity analysis indicated that no data from a single study significantly altered the final conclusion. The results were not affected by either regional or ethnic differences.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis should be considered. Firstly, the studies were mostly from Chinese where green tea is more popular than in other nations. As such, there may be limited generalizability of the results to other ethnic groups. Future studies should expand the scope of inclusion to consider other ethnic and racial groups. Secondly, only studies included by the selected databases were included for analysis and some relevant published studies or unpublished studies with null results might have been missed. Thirdly, all the included studies were retrospective, prospective and cross sectional studies. The lack of randomized clinical trials could increase the risk of bias. Furthermore, because of the lack of sufficient studies included, the results of hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and chronic disease groups should be interpreted with caution. Despite the limitations, we have minimized the bias through the whole process by optimizing the study identification, data selection and statistical analysis process. Efforts have also been made to assess the level of publication bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study is the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date to have assessed the association between green tea drinking and liver disease. Our results suggested that green tea intake is a protective factor for liver diseases. Still, future large-scale randomized clinical trials are needed to validate these conclusions.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Li Y, Chang SC, Goldstein BY, Scheider WL, Cai L, You NC, Tarleton HP, Ding B, Zhao J, Wu M, Jiang Q, Yu S, Rao J, Lu QY, Zhang ZF, Mu L. Green tea consumption, inflammation and the risk of primary hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Wu FS, Deng X, Liang J. The status quo of nano drug in targeted therapy of liver cancer research (in Chinese) Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine on Liver Diseases. 2014;022:118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu Y, Xing HC. The analysis of prevalence and risk factors of primary liver cancer (in Chinese) Chinese Journal of Liver Diseases. 2014;02:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YL, Chang YY, Yang DJ, Tzang BS, Chen YC. Beneficial effects of noni (Morinda citrifoliaL). Juice on livers of high-fat dietary hamsters. Food Chemistry. 2013;140:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian Song. Fresh Green Tea (in Chinese) Food and Health. 2014;02:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fon Sing M, Yang WS, Gao S, Gao J, Xiang YB. Epidemiological studies of the association between tea drinking and primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20:157–165. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283447497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang ZQ, Zhong SC. An epidemiologictrial of using green tea to prevent liver cancer (in Chinese) Guang Xi Prev Med. 1995;1:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu YC, Shen HB, Niu JY, Shen J, Zhou L, Li WG, Chen JG, Yao HY. An intervention trial withgreen tea on high risk population of primary liver cancer (in Chinese) Cancer Res Prev Treatment. 1998;25:223–225. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan YB, Wang ZQ, Hu XX, Jiang QW, Yu SZ. Cohort study of drinking green tea on liver disease (in Chinese) Pract Prev Med. 2005;12:1016–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen HB, Xu YC, Shen J, Niu JY. The relationship between habit of drinking green tea and primary liver cancer: a casecontrol study (in Chinese) Chin J Behav Med Sci. 1996;5:88–89. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao JP, Shen XN, Wu M, Lu RF. Epidemiologic surveyon the association between green tea intake and fatty liver disease (in Chinese) China Public Health. 2002;18:385–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mu LN, Zhou XF, Ding BG, Wang RH, Zhang ZF, Jiang QW. Study on the protective effect of green tea on gastric, liver and esophagealcancer (in Chinese) Chin J Prev Med. 2003;37:171–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Coffee and tea consumption areassociated with a lower incidence of chronic liver disease inthe united states. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1928–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mu DL, Yu JX, Li DF, Yang CR, Sun J, Song YF. Observation on the therapeutic effect inthe treatment of 26 patients with fatty liver by tea pigmentcapsules (in Chinese) J Norman Bethune Univ Med Sci. 1997;23:528–530. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia PJ, Zhao GX, Ouyang JD, Yang YH, Guo YT, Wang JP, Zhang CH. Investigation of the relationship between incidence of fatty liver and living style and diet (in Chinese) Chin J of Behavioral Med Sci. 2005;114:1037–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamia C, Lagiou P, Jenab M, Trichopoulou A, Fedirko V, Aleksandrova K, Pischon T, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Boutron-Ruault MC, Fagherazzi G, Racine A, Kuhn T, Boeing H, Floegel A, Benetou V, Palli D, Grioni S, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Dik VK, Bhoo-Pathy N, Uiterwaal CS, Weiderpass E, Lund E, Quirós JR, Zamora-Ros R, Molina-Montes E, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, Dorronsoro M, Lindkvist B, Wallström P, Nilsson LM, Sund M, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bradbury KE, Travis RC, Ferrari P, Duarte-Salles T, Stepien M, Gunter M, Murphy N, Riboli E, Trichopoulos D. Coffee, tea and decaffeinated coffee in relation to hepatocellular carcinoma in a European population: Multicentre, prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2014;136:1899–1908. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagano J, Kono S, Preston DL, Mabuchi K. A prospective study of greentea consumption and cancer incidence, Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:150–154. doi: 10.1023/a:1011297326696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nechuta S, Shu XO, Li HL, Yang G, Ji BT, Xiang YB, Cai H, Chow WH, Gao YT, Zheng W. Prospective cohort study of tea consumption and risk of digestive system cancers: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1056–1063. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao S. Epidemiological studies of primary liver cancer in urban shanghai (in Chinese) Fudan University Master Dissertation. 2011:32–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L. An epidemiological study on fatty liver of employees in fertilized plant of a petrochemical corporation (in Chinese) Anhui Medical University Master Dissertation. 2001:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan LY. A 1:2, matched case control study on risk factors of primary hepatic carcinoma, (in Chinese) Da Lian Medical University Master Dissertation. 2008:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang HY, Yang SC, Jane CJ, Chen JR. Beneficial effects of catechin-rich green tea and inulin on the body composition of overweight adults. BJ Nutr. 2012;107:749–754. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511005095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chacko SM, Thambi PT, Kuttan R, Nishigaki I. Beneficial effects of green tea: A literature review. Chinese Medicine. 2010;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ui A, Kuriyama S, Kakizaki M, Sone T, Nakaya N, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Hozawa A, Nishino Y, Tsuji I. Green tea consumption and the risk of liver cancer in Japan: the ohsaki cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1939–1945. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]