Abstract

The laterality in the embryo is determined by left-right asymmetric gene expression driven by the flow of extraembryonic fluid, which is maintained by the rotary movement of monocilia on the nodal cells. Defects manifest by abnormal formation and arrangement of visceral organs. The genetic etiology of defects not associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia is largely unknown. In this study, we investigated the cause of situs anomalies, including heterotaxy syndrome and situs inversus totalis, in a consanguineous family. Whole-exome analysis revealed a homozygous deleterious deletion in the WDR16 gene, which segregated with the phenotype. WDR16 protein was previously proposed to play a role in cilia-related signal transduction processes; the rat Wdr16 protein was shown to be confined to cilia-possessing tissues and severe hydrocephalus was observed in the wdr16 gene knockdown zebrafish. The phenotype associated with the homozygous deletion in our patients suggests a role for WDR16 in human laterality patterning. Exome analysis is a valuable tool for molecular investigation even in cases of large deletions.

Introduction

Visceral asymmetry is determined through embryonic ciliary motion, and normal function of the motile cilia plays a key role in the patterning of left-right (L-R) asymmetry.1 A failure to generate the normal L-R asymmetry during early stages of embryogenesis may result in severe anatomical abnormalities, including heterotaxy syndrome (HS), which consists of abnormal L-R axis arrangement of the abdominal and thoracic viscera, and situs inversus totalis (SIT), which manifests by mirror image asymmetry of the internal viscera. HS is at times accompanied by complex congenital cardiovascular anomalies, whereas SIT is frequently associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD).2 The prevalence of situs anomalies in the European population is approximately 1 in 22 200 live births (EUROCAT Access Prevalence Tables. Available at: http://www.eurocat-network.eu/ACCESSPREVALENCEDATA/PrevalenceTables. Accessed 18 June 2014). Unlike PCD, where multiple genes are implicated in the disease mechanism, variants in only few genes are currently known to cause isolated, non-syndromic laterality defects.3, 4, 5 We now report on another player in L-R asymmetry patterning, identified through exome analysis in patients from a consanguineous family who presented with HS and SIT.

Patients and Methods

Patients

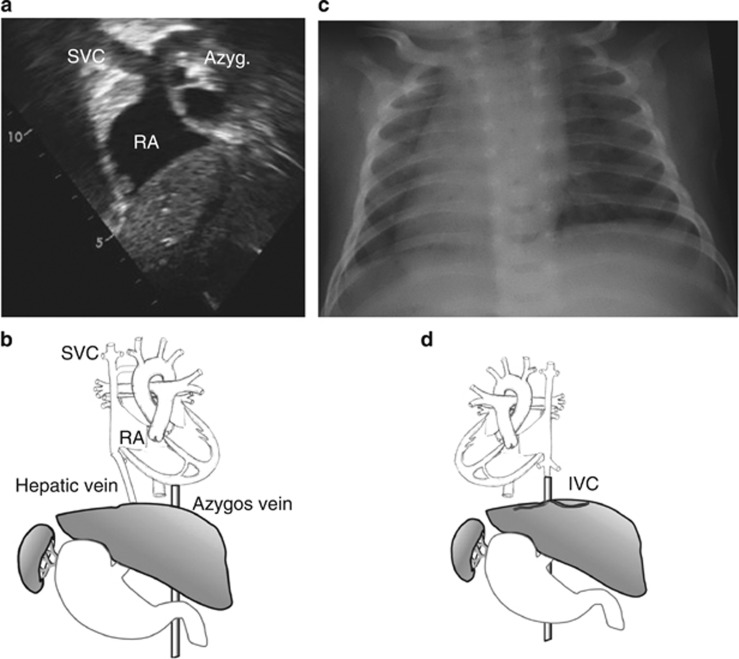

Patient II-3 is a female, the third child of consanguineous Palestinian parents (Figure 1a). Her birth and early development were uneventful. At 19 months of age, she was admitted because of acute gastroenteritis. The physical examination and chest X-ray demonstrated a left-sided heart and an US showed abdominal situs inversus. Echocardiogram demonstrated levocardia with interrupted inferior vena cava, all of which were consistent with HS (Figure 2a and b). Brain CT scan was normal, excluding hydrocephalus and her growth and development, followed till 7 years, were normal. Her younger brother, patient II-4, was brought to medical attention at 7 weeks of age because of viral bronchiolitis. Physical examination, chest X-ray and abdominal US were all consistent with SIT (Figure 2c and d). Nasal NO was normal (580 ppb) indicating normal ciliary function; electron microscopy examination of the nasal epithelium obtained by brush biopsy revealed normal ciliary structure, excluding PCD. On follow-up (current age 4 years), his growth and development were normal. The parents and two older sibs were healthy, with normal cardiac and abdominal situs determined by chest X-ray and abdominal US.

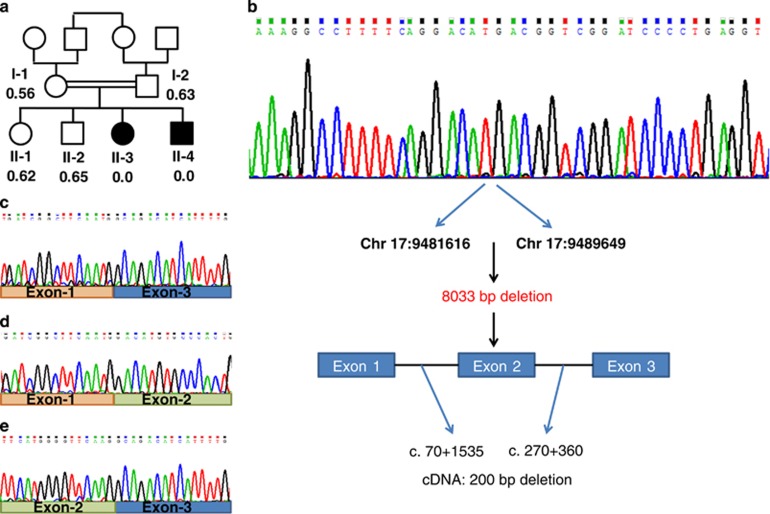

Figure 1.

(a) Family pedigree and the WDR16 deletion. The patients are represented by filled symbols. The signal intensity of the Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification analysis is shown below the symbols (control intensity 1.01–1.07, n=22). (b) WDR16 genomic sequence of patient II-3 around the breakpoint and schematic representation of the chr17.hg19:g.9481617_9489649del8033. (c) WDR16 cDNA sequence analysis of patient II-3 lacking exon-2 and of an unrelated control (d–e). The full colour version of this figure is available at European Journal of Human Genetics online.

Figure 2.

Abnormal arrangement of patients' organs (a) Echocardiogram of patient II-3 from the subcostal short axis view: A large azygos vein draining into the superior vena cava due to inferior vena cava interruption. (b) Schematic drawing of patient II-3 anatomy showing normal cardiac situs and inverted visceral arrangement: inferior vena cava interruption, azygos continuity to the superior vena cava, left-sided liver and right-sided stomach and spleen. (c) Chest X-ray of patient II-4 demonstrating SIT: the cardiac apex and the stomach bubble are to the right. (d) Schematic drawing of patient II-4 anatomy showing mirror image cardiac and visceral arrangement: dextrocardia, left-sided liver and right-sided stomach and spleen. Abbreviations: SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava; RA, right atrium; Azyg, azygos vein.

Methods

Homozygosity mapping

In order to identify disease-linked homozygous regions, DNA samples of patient II-3 and II-4 were analyzed using Affymetrix Gene-Chip Human Mapping 250 K NspI Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as previously described.6 Homozygous regions were manually detected with a minimum threshold of 2 Mb and up to 3 intervening heterozygous calls per 2 Mb.

Whole-exome analysis

Exonic sequences were enriched in the DNA samples of patient II-3 and II-4 using SureSelect Human All Exon 50 Mb Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequences were determined by HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and 100-bp were read paired-end. Reads alignment and variant calling were performed with DNAnexus software (Palo Alto, CA, USA) using the default parameters with the human genome assembly hg19 (GRCh37) as a reference. Parental consent was given for DNA studies. The study was performed with the approval of the ethical committees of Hadassah Medical Center and the Ministry of Health.

cDNA analysis

cDNA was prepared from the patients and a control fresh lymphocytes using Maxima 1st strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The region encompassing exon 2 of WDR16 was amplified by PCR reaction using Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) with the forward primer 5′-GGAACTTGACGCCGTGAT-3′ and the reverse primer 5'-GTCCCATTTCCAGCAGTCATA-3′. The resultant fragments were separated using 2% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis and their sequence determined by Sanger sequencing.

Segregation analysis

DNA of all available family members and 22 unrelated controls of similar ethnicity was analyzed by Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification, using a synthetic probe specific for a unique sequence within exon 2 (Chr17.hg19:g.9487579_9487670) and exon 3 (Chr17.hg19:g.9489076_9489149) of the WDR16 gene. The probe was labeled using the SALSA MLPA KIT P300-A1 Human DNA Reference-2 (MRC-Holland).

The variant data and phenotypes are archived and available at http://wdr16.lovd.nl (patient ID's 20017 and 24130).

Characterization of the breakpoint in the WDR16 gene

In order to identify the genomic position of the breakpoint, several sets of primers were designed at different locations in the introns adjacent to exon 2. In all reactions, DNA of the patient and two healthy control individuals was used. The amplified fragments were analyzed in 2% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis. The final set of primers was: forward primer: 5′-CATGAAGGTGGTCCCAACA-3′ and the reverse primer: 5′-GATAGCTACCCTTCTTGGTGAAA-3′.

Results

The homozygosity mapping revealed eight large homozygous regions (Supplementary Table 1) in the DNA samples of patients II-3 and II-4. These regions encompassed numerous protein-coding genes and we therefore opted for exome analysis.

The exome analyses of the DNA of patient II-3 and II-4 yielded 80.03 and 49.61 million confidently mapped reads, respectively (mean coverage X86.65 and X58.59, respectively). Following alignment to the reference genome, 19 919 and 19 885 variants were noted on target, respectively. We removed variants that were not shared between the two patients, were called less than X5, heterozygous, synonymous (and >3 bp away of splice site), present in dbSNP132 or at the Hadassah in house database or predicted benign by Mutation Taster software.7 Six variants survived this filtering process but none of them segregated with the phenotype in the family (Supplementary Table 1). However, coverage analysis comparing the patients exonic coverage to that of the same day samples (n=8) revealed that exon 2 of the WDR16 gene (gi:124028511) was not covered at all in the patients' samples but was deeply covered (x46-60) in the other samples. WDR16 (NM_145054) consists of 14 exons, encoding 620 amino acids (NP_659491.4). As exon 2 spans 200 bp, a framesfhift variant c.70+1535_270+360del, p.(His25Arg fs*8) would result. The finding was confirmed both by cDNA analysis, which disclosed an abnormally short fragment, skipping exon 2 sequence (Figure 1c), and by the results of the Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification analysis, which confirmed segregation of the deletion in the family, with an undetectable signal for the patients, a signal of 0.56–0.65 in the DNA samples of the parents and two healthy sibs and a signal of 1.01–1.07 in the 22 ethnically matched control samples (Figure 1a). The signal of exon 3 of the WDR16 gene was comparable in all the samples. Serial PCR reactions using intronic primer sets encompassing exon 2, resulted in the amplification of a 448 bp genomic fragment, which contained the breakpoint. Sanger sequencing of that fragment identified the exact breakpoint (chr17.hg19:g.9481617_9489649del8033, Figure 1b).

Discussion

L-R asymmetry development in early embryogenesis is fundamental among vertebrates. According to the generally accepted model, the initiation of asymmetry is coordinated by nodal cilia, which create leftward flow.2 The flow forms concentration gradient detected by sensory immotile cilia producing intracellular signal transduction.8 This Nodal signaling pathway activates an asymmetric developmental program in visceral primordial cells within the lateral plate mesoderm.8 Nodal cilia share many structural features with other motile cilia, and impaired function of the nodal cilia is likely an integral part of PCD; however, owing to randomization of L-R axis development, it is clinically manifested in only half of the PCD patients.8 Beyond the embryonic period, motile cilia function is essential in several human organs and tissues, mainly the respiratory tract and sperm tails (flagella).1 Consequently, ciliary dysfunction manifests predominantly by sinusitis, bronchitis and male infertility and less frequently by hydrocephalus, retinal degeneration, sensory hearing loss and polycystic kidney disease.

The present report describes the identification of WDR16 as a putative novel player in L-R asymmetry development. WDR16 is a member of the WD40 repeat-protein family, which functions in protein–protein interactions. On the basis of its expression timeline, which parallels that of the cilia-related proteins Spag6 (sperm-associated antigen 6) and Hydin, WDR16 was proposed to play a role in cilia-related signal transduction processes.9 Support was provided by the tissue expression in rat, where the protein is solely expressed in cilia-containing tissues, including testis, cultured ependymal cells, lung and brain. Furthermore, the wdr16 knockdown zebrafish invariably developed severe hydrocephalus. Large interspecies variability in the phenotypic manifestation of ciliary gene defects is not uncommon; for example, Hydin variants in mice cause hydrocephalus with abnormal motility of the ependymal cilia10 but PCD in human;11 similarly, Spag1 variants cause hydrocephalus in fish but PCD in human.12

There is a growing body of evidence that these two laterality disorders, SIT and HS, are actually part of a phenotypic continuum, underlined by the same genetic defects. Variants in the ZIC3 gene, which are thought to account for ~1% of HS cases,3 were also found to cause SIT13 and over 6% of PCD patients were found to have HS.14 Also, 18/43 patients with congenital heart defects with HS were found to have PCD.15 Moreover, we have recently reported a consanguineous family with both SIT and HS underlined by a single deleterious variant in the CCDC11 gene.5

Here, we describe a homozygous genomic deletion in the WDR16 gene in individuals with both HS and SIT who were otherwise healthy. The deletion which occurs early in the gene would not allow for the generation of even a shorter functional protein. A normally occurring shorter (552 residues) protein, lacking exon 2 and the first 4 bp of exon 3, was reported in human (NP_001074025) and rodents. Nonetheless, the shorter transcript, which would correspond to the 552 amino acids protein, was not detected in cDNA of our control samples and exon 2 was skipped in the patient cDNA, whereas exon 3 was fully included, thus causing a frameshift. The possibility of a translation from an in-frame downstream ATG seems unlikely given that the next Met is only at residue 173, resulting in a protein that lacks the evolutionary conserved WD40 domain at residues 100–141.

The relatively benign clinical course of our patients, with the absence of significant hemodynamic changes imposed by the laterality defect, attests perhaps to the laterality-specific role of the WDR16 protein. Still, the patients would be followed well into adulthood for possible late manifestations of ciliary dysfunction such as male infertility.

Finally, the present report underscores the importance of coverage data analysis as part of exome sequencing in detecting large copy number variants.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H: When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007; 8: 880–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabin CJ: The key to left-right asymmetry. Cell 2006; 127: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware SM, Peng J, Zhu L et al: Identification and functional analysis of ZIC3 mutations in heterotaxy and related congenital heart defects. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 74: 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford RN, Roessler E, Burdine RD et al: Loss-of-function mutations in the EGF-CFC gene CFC1 are associated with human left-right laterality defects. Nat Genet 2000; 26: 365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perles Z, Cinnamon Y, Ta-Shma A et al: A human laterality disorder associated with recessive CCDC11 mutation. J Med Genet 2012; 49: 386–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardson S, Shaag A, Kolesnikova O et al: Deleterious mutation in the mitochondrial arginyl-transfer RNA synthetase gene is associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 857–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D: MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods 2010; 7: 575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiba S, Shiratori H, Kuo IY et al: Cilia at the node of mouse embryos sense fluid flow for left-right determination via Pkd2. Science 2012; 338: 226–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschner W, Pogoda HM, Kramer C et al: Biosynthesis of Wdr16, a marker protein for kinocilia-bearing cells, starts at the time of kinocilia formation in rat, and wdr16 gene knockdown causes hydrocephalus in zebrafish. J Neurochem 2007; 101: 274–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe HR, Shaw MK, Farr H, Gull K: The hydrocephalus inducing gene product, Hydin, positions axonemal central pair microtubules. BMC Biol 2007; 5: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbrich H, Schmidts M, Werner C et al: Recessive HYDIN mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia without randomization of left-right body asymmetry. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 91: 672–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MR, Ostrowski LE, Loges NT et al: Mutations in SPAG1 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia associated with defective outer and inner dynein arms. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 93: 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandro LC, Casey B, Siu VM: Situs inversus totalis and a novel ZIC3 mutation in a family with X-linked heterotaxy. Congenit Heart Dis 2013; 8: E36–E40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW et al: Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation 2007; 115: 2814–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhleh N, Francis R, Giese RA et al: High prevalence of respiratory ciliary dysfunction in congenital heart disease patients with heterotaxy. Circulation 2012; 125: 2232–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.