Abstract

Both lateral hypothalamic orexinergic neurons and hindbrain catecholaminergic neurons contribute to control of feeding behavior. Orexin fibers and terminals are present in close proximity to hindbrain catecholaminergic neurons, and fourth ventricular (4V) orexin injections that increase food intake also increase c-Fos expression in hindbrain catecholamine neurons, suggesting that orexin neurons may stimulate feeding by activating catecholamine neurons. Here we examine that hypothesis in more detail. We found that 4V injection of orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) produced widespread activation of c-Fos in hindbrain catecholamine cell groups. In the A1 and C1 cell groups in the ventrolateral medulla, where most c-Fos-positive neurons were also dopamine β hydroxylase (DBH) positive, direct injections of a lower dose (67 pmol/200 nl) of orexin-A also increased food intake in intact rats. Then, with the use of the retrogradely transported immunotoxin, anti-DBH conjugated to saporin (DSAP), which targets and destroys DBH-expressing catecholamine neurons, we examined the hypothesis that catecholamine neurons are required for orexin-induced feeding. Rats given paraventricular hypothalamic injections of DSAP, or unconjugated saporin (SAP) as control, were implanted with 4V or lateral ventricular (LV) cannulas and tested for feeding in response to ventricular injection of orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat). Both LV and 4V orexin-A stimulated feeding in SAP controls, but DSAP abolished these responses. These results reveal for the first time that catecholamine neurons are required for feeding induced by injection of orexin-A into either LV or 4V.

Keywords: hypocretin, orexin, ventrolateral medulla, feeding, catecholamine neurons

orexins (or hypocretins) are neuropeptides expressed exclusively by neurons with cell bodies in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) (11, 46). Orexin neurons project widely from LHA to sites throughout the brain, including cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord (33, 36). Similarly, expression of orexin receptor genes has been observed in brain regions that integrate central and visceral signals related to gastrointestinal functions, metabolism, blood pressure control, and respiratory rhythms (29, 30, 53). Orexin neurons are now recognized as important participants in multiple physiological functions including arousal and the sleep/wake cycle (45), respiration (32), reward (10, 21), and feeding behavior (2, 3, 46).

Orexins were first identified as feeding regulatory peptides. Of the two orexin peptides that have been identified, orexin-A and orexin-B (46), orexin-A appears to be the isoform most important for the feeding response. Injections of orexin-A into lateral ventricle (LV) (14, 46, 51, 60), fourth ventricle (4V) (2, 34, 59), and intrahypothalamic sites (13, 14, 51) have been shown to increase feeding. Nevertheless, the neural substrates through which orexin stimulates food intake have not been identified.

It has been known for decades that central administration of norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E) also potently increases food intake (6, 22–24, 38). More recently, it has been shown that orexin fibers and terminals, as well as orexin receptors, are expressed in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and ventrolateral medulla in close proximity to catecholamine neurons (30, 33, 59). In addition, catecholamine neurons are activated by orexin, as indicated by increased c-Fos expression (59). Together, these results led us to the hypothesis that activation of catecholamine neurons by orexin terminals in the hindbrain may contribute importantly to orexin-induced feeding. To test this hypothesis, we first injected orexin-A into the 4V to examine further the effects of these injections on c-Fos expression in catecholamine cell groups. We also measured feeding in response to injection of orexin-A directly into the overlap area of catecholamine cell groups A1 and C1 (A1/C1), an area expressing c-Fos in response to glucose deficit and an area of special significance for glucoprivic control of feeding (25–27). Both catecholamine and orexin neurons mediate numerous physiological responses, as discussed above. To test the importance of catecholamine neurons, specifically for orexin-induced feeding, we tested feeding in response to ventricular orexin-A in rats injected previously into the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVH) with the retrogradely transported (4) and selective catecholamine neurotoxin, anti-dopamine β hydroxylase (DBH)-saporin (DSAP) (56). When injected into the PVH, DSAP destroys a large percentage of catecholamine neurons with collateral projections throughout the hypothalamus. Because the specific terminal areas and circuitry associated with orexin-induced feeding have not been fully described, we examined the effects of the DSAP lesion on feeding induced by both LV and 4V orexin injections. Results reveal that orexin neurons produce widespread activation of hindbrain catecholamine neurons and that catecholamine neurons are required for stimulation of feeding by ventricular orexin-A injections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Simonsen Laboratories (Gilroy, CA) and housed individually in an animal care facility approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Rats were maintained on a 12:12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to pelleted rodent food (Rodent diet 5001; LabDiet, St. Louis, MO; 3.36 kcal/g; 28.5% protein, 13.5% fat, and 58.0% carbohydrates) and tap water. All experimental procedures were approved by Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which complies with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Intraventricular injections.

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and stereotaxically implanted with a 26-gauge stainless guide cannula directed at the 4V or left LV using coordinates determined from The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (35) and verified by pilot studies and histological examination of test sites. Coordinates used for 4V cannulas were 1.55 mm rostral to the occipital suture, 0 mm lateral to midline, and 6.4 mm ventral to the skull surface. For LV cannulas, coordinates were 1.0 mm caudal to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to midline, and 3.9 mm ventral to brain surface. Experiments were conducted beginning 1 wk after surgery. Drugs or vehicle solutions were delivered into the LV or 4V over a 5-min period using a Gilmont micrometer syringe (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). The accuracy of cannula placement in rats for all experiments was further confirmed by histological analysis at the end of each experiment. Overall, >90% of 4V or LV cannulas, and of A1/C1 cannulas (see below), were correctly implanted. Only data from these rats are presented in this study.

Measurements of food intake after ventricular orexin injections.

Food intake was measured in 4-h tests after injection of orexin or saline at 9:30 am. Orexin-A (Peptides International, Louisville, Kentucky) was dissolved in 0.9% saline and injected into the 4V or LV at 0.5 nmol in 3 μl (34, 51, 59). At the beginning of the LV and 4V experiments, body weights of rats were between 400 and 460 g.

Local injection of orexin-A into the A1/C1 area.

For direct injections of drugs into A1/C1, 26-gauge cannulas were implanted bilaterally into this region. Initial body weights of rats used in these experiments were between 360 and 420 g. Cannulas were implanted at a 14-degree angle with respect to the sagittal plane to avoid damage to the NTS and to minimize diffusion into that area along the cannula tract. The coordinates were 0 mm rostral to the occipital suture, 4.0 mm lateral to midline, and 8.6 mm ventral to the skull surface for A1/C1 (35). After a 1-wk recovery period, food intake was measured in the rats' home cages in response to bilateral injections of orexin-A (67 pmol/200 nl), 5-thio-D-glucose (5TG; 24 μg/200 nl), or vehicle (saline; 200 nl) into A1/C1. Injections were delivered over a 5-min period using a Gilmont micrometer syringe (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). At the end of experiments, the accuracy of cannula placement was confirmed by examining the proximity of the cannulas to DBH-immunoreactive (ir) neurons in the A1/C1 region.

Microinjection of immunotoxin.

To selectively lesion hypothalamically projecting catecholamine neurons in the hindbrain, retrogradely transported immunotoxin, DSAP (82 ng/200 nl; Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA), or unconjugated saporin (SAP) control (17.2 ng/200 nl), dissolved in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4), was infused into the hypothalamus, as previously described (40, 43). Rats were anesthetized using isoflurane. Injections were made with a Picospritzer through a pulled glass capillary pipette (30-μm tip diameter) positioned just dorsal to the targeted site in the PVH at the following coordinates: 1.8 mm caudal to bregma, 0.4 mm lateral to midline, and 7.4 mm ventral to the dura mater. The amount of unconjugated SAP in the control solution was equal to the amount of SAP present in the DSAP conjugate (21%), as indicated in the manufacturer's product information. Previous work from our laboratory comparing SAP and noninjected controls demonstrated that SAP used in this way does not produce behavioral or histological signs of toxicity or impairment of feeding responses (40, 43). After DSAP or SAP injections, rats were implanted with LV or 4V cannulas, as described above. A 3-wk interval was allowed between the DSAP injection and further experimentation to permit complete degeneration of retrogradely lesioned neurons.

As an ante mortem screening test to assess the effectiveness of DSAP lesion, SAP controls and DSAP-treated rats were tested for 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG)-induced feeding, a response that is impaired by this lesion (40). 2DG (200 mg/kg body wt in 0.9% sterile saline; Sigma-Aldrich) or 0.9% saline control was injected subcutaneously at 9:30 am, and food intake was measured during the subsequent 4 h. Any DSAP rat that ate more than 2.0 g of food in this screening test was eliminated from the study. Efficacy of the lesion was further analyzed at the completion of behavioral testing by quantifying DBH-ir cell bodies in hindbrain catecholamine cell groups, as described below. To be included in the data analysis, DSAP rats were required to have a reduction of at least 70% in DBH cell numbers in A1, A1/C1 overlap, and medial part of C1 (C1m), compared with the respective averages in the control SAP rats. Overall, about 90% of rats had successful lesions. There were no differences in body weight between SAP and DSAP rats before (399 ± 11 g vs. 410 ± 13 g) or at 7 wk (441 ± 13 g vs. 455 ± 5 g) after PVH injection (Ps > 0.3).

Immunohistochemistry.

Expression of c-Fos in the hindbrain by orexin-A injection was investigated in 4V cannula-implanted rats. The patency and correct placement of cannulas were first assessed by measuring 4-h food intake after injection of 5TG (135 μg/3 μl), a known stimulus for food intake when injected intraventricularly (39). Only rats that ate more than 2 g during a 4-h period after 5TG injection were used in the c-Fos study. The accuracy of cannula placement was further confirmed by histological analysis at the end of the experiment. Initial body weights of rats used in this experiment were between 420 and 450 g.

After extensive habituation to handling, rats were euthanized by deep isoflurane-induced anesthesia (Halocarbon Products), 90 min after orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) or saline injection (at 9:30 am) into 4V. Just before cessation of the heartbeat, rats were perfused transcardially with PBS (pH 7.4) followed by 4% formaldehyde in PBS. After perfusion, brains and adrenal medullas were rapidly removed and placed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS overnight at 4°C, then transferred to 12.5% and 25% sucrose in PBS for 24 h each, then sectioned coronally on a cryostat at 40-μm thickness. Brain sections were collected into two or three serial sets for immunohistochemical staining, depending on the cell group and its distribution, as described below. For each area, the same number of sections were collected for each rat.

For double immunofluorescence staining of brain tissues, sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-DBH (1:10,000; Millipore, San Jose, CA) and goat anti-c-Fos (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies for 2 to 3 days (at room temperature), then washed and sequentially incubated with donkey anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 488 and donkey anti-goat-Cy3 antibodies (all at 1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 4 h, and then coverslipped with ProLong Gold medium (Life Technology, Grand Island, NY). Slides were examined using a Zeiss Axiomat microscope, and images were collected for quantification of immunoreactive neurons. Catecholamine cell groups were defined as described by The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (35). DBH- and c-Fos-positive cells were counted bilaterally in two (for A2 subregions and A5v) or three (for all other regions) consecutive sections from the following regions for each rat. Anatomical levels for each region were (distance in mm caudal from bregma) A1, 14.4-14.1; A1/C1, 13.7-13.4; C1m, 13.0-12.7; C1r (rostral C1), 12.2-11.9; A2m (middle A2), 14.3-14.1; A2r (rostral A2), 13.9-13.7; C2c (caudal C2), 13.6-13.3; C2m (medial C2), 13.1-12.7; A5d (dorsal A5), 10.6-10.2; A5v (ventral A5), approximately 10.2; A6, 10.0-9.7; and A7, 8.6-8.4. c-Fos-positive cells were also counted in the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV) at the level of A2m. To assess the lesion produced by DSAP injection, DBH-ir cells were quantified in the above catecholamine groups, except as noted. The presence of DBH terminals in PVH and other hypothalamic sites was examined, but not quantified. However, all DSAP rats with significant loss of catecholamine neurons in the above areas also had significant loss of DBH terminals in the hypothalamus, as reported previously (40, 43).

Statistical analysis.

All results are presented as means ± SE. For statistical analysis of data, we used t-tests, one-way ANOVAs, or two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs, as appropriate. After significance was determined by ANOVA, multiple comparisons between individual groups were tested using a post hoc Fisher least significant difference test. Confidence limits for significance were set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Fourth ventricular orexin-A injection increased c-Fos expression in hindbrain catecholamine neurons.

After preliminary tests, a dose of 0.5 nmol/rat orexin-A, which significantly increases food intake during the 4 h after the injection, was selected for 4V or LV injections throughout this study.

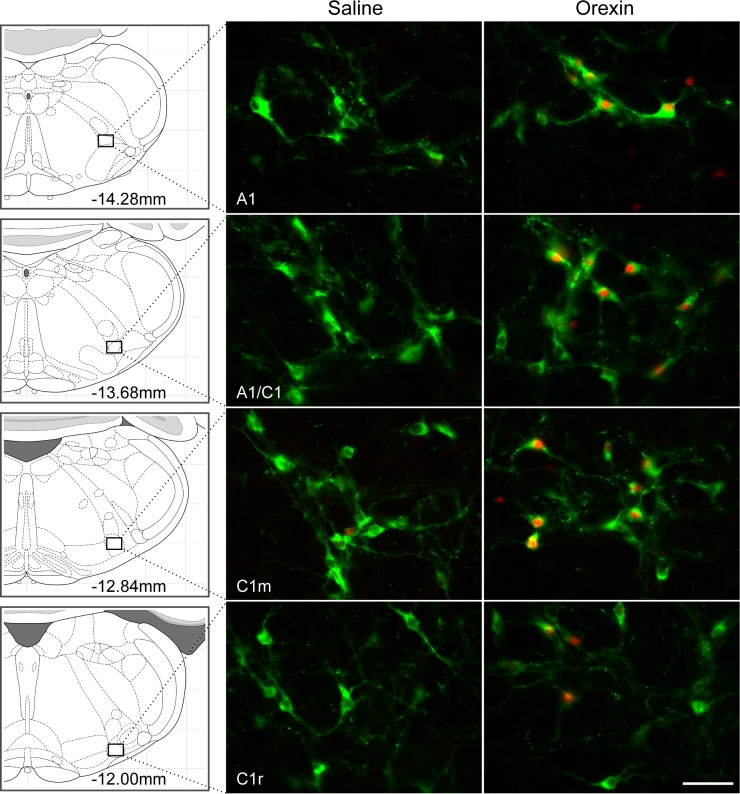

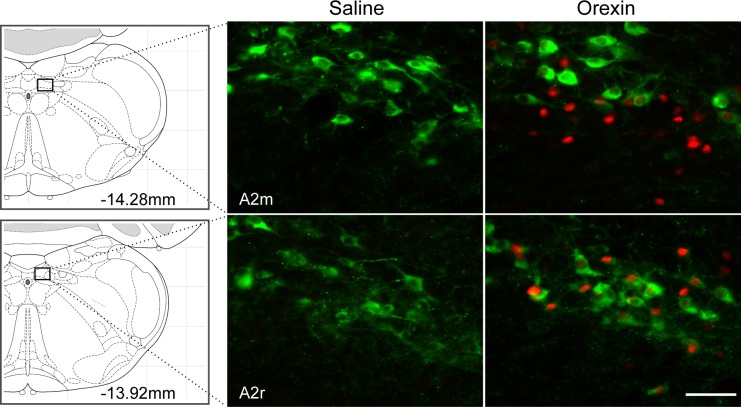

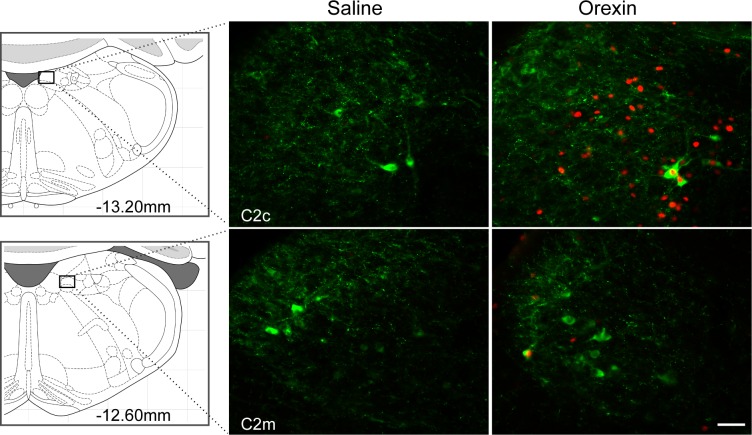

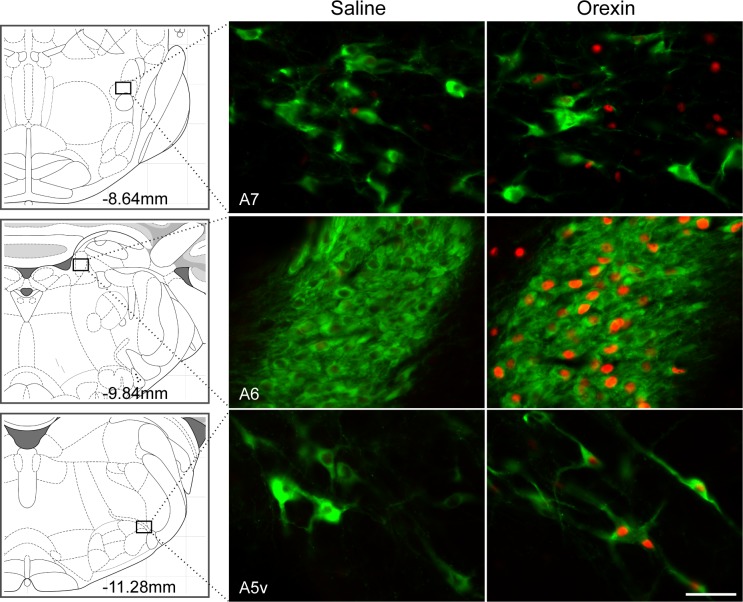

Activation of hindbrain sites by 4V orexin-A injection was investigated. Orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) or saline was injected into the 4V, and rats were euthanized 90 min later (n = 5/group). Brain tissue was processed to detect c-Fos- and DBH-ir. In ventrolateral medulla, numbers of neurons expressing c-Fos-ir and c-Fos- plus DBH-ir were increased in A1 through C1 regions (Ps < 0.001; Table 1 and Fig. 1). With the exception of rostral C1, 42% to 43% of DBH-ir neurons were c-Fos-positive and most (68–72%) of the c-Fos-positive cells were DBH-ir in A1-C1 regions. In rostral C1, 44% of c-Fos-positive neurons was DBH-ir and only 14% of DBH-ir neurons were c-Fos positive. c-Fos-positive cells were also found throughout the NTS. However, cells colabeled for c-Fos/DBH were present mainly in rostral A2 (Ps < 0.001; Table 1 and Fig. 2) and were sparse in C2 (Fig. 3). In rostral A2, 66% of c-Fos-positive cells were DBH-ir but only 26% of DBH-ir neurons were c-Fos-positive. In the mid rostro-caudal level of A2, 30% of c-Fos-positive cells were DBH-ir but only 11% of DBH-ir neurons were c-Fos-positive. At the same coronal plane as A2m, more c-Fos-positive cells were found in DMV area (P < 0.001; Table 1). DBH and c-Fos in cell groups A5-A7 were not quantified. However, about half of the DBH-positive cells in ventral A5 region were activated by orexin-A (Fig. 4), but no c-Fos-positive cells were found in the dorsal part of A5. In A6, many or most DBH-positive neurons appeared to be activated by orexin-A (Fig. 4). Only a few c-Fos-ir cells were found in the vicinity of A7, but these did not express DBH (Fig. 4). Some C3 neurons also expressed c-Fos, but because it was close to the injection site, c-Fos in C3 area was not quantified.

Table 1.

Numbers of c-Fos- and DBH-positive cells in hindbrain regions after 4V injection of orexin-A

| Treatment Region and Staining | Saline | Orexin-A |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | ||

| c-Fos (%) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 10.9 ± 1.6* (72) |

| DBH (%) | 17.6 ± 0.7 | 18.5 ± 0.8 (43) |

| Double | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 1.3* |

| A1/C1 | ||

| c-Fos (%) | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 12.3 ± 1.1* (71) |

| DBH (%) | 20.8 ± 0.7 | 20.8 ± 0.7 (42) |

| Double | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 0.9* |

| C1m | ||

| c-Fos (%) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 12.0 ± 1.1* (68) |

| DBH (%) | 19.6 ± 0.8 | 19.4 ± 0.9 (42) |

| Double | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.9* |

| C1r | ||

| c-Fos (%) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.7* (44) |

| DBH (%) | 15.5 ± 0.7 | 14.7 ± 0.5 (14) |

| Double | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.3* |

| A2r | ||

| c-Fos (%) | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 15.5 ± 1.7* (66) |

| DBH (%) | 40.8 ± 1.6 | 39.9 ± 1.3 (26) |

| Double | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 10.3 ± 1.3* |

| A2m | ||

| c-Fos (%) | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 9.2 ± 1.1* (30) |

| DBH (%) | 23.1 ± 0.7 | 24.8 ± 1.1 (11) |

| Double | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.6* |

| DMV | ||

| c-Fos | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 11.2 ± 1.7* |

Values are means ± SE. Numbers of c-Fos-, dopamine β hydroxylase (DBH)-, or double c-Fos/DBH-positive cells in hindbrain catecholamine cell regions, 90 min after a fourth ventricular (4V) injection of orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) or saline, are shown. Numbers are averages for each region from 5 rats. Due to more limited topographical distribution, 2 sections per rat were counted at A2r, A2m, and A5v. Three sections per rat were counted for all other regions. Percentages of double-stained cells in c-Fos- or DBH-immunoreactive (ir) population after orexin-A treatment are shown in parentheses.

P < 0.001 vs. saline-injected rats.

Fig. 1.

Dopamine β hydroxylase (DBH) and c-Fos double-immunofluorescence staining in ventrolateral medulla (VLM) catecholamine cell groups. Coronal sections at A1, A1/C1 overlap, C1m, and C1r regions from saline- or orexin-A-treated rats are shown. Green labeling indicates DBH-immunoreactive (DBH-ir) and red indicates c-Fos-immunoreactive (c-Fos-ir). Orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) significantly stimulated c-Fos expression in these VLM areas, primarily in DBH-positive cells. Schematic representations of coronal brain sections showing each region are presented at left, and distance (in mm) caudal to bregma is shown. Bar, 25 μm.

Fig. 2.

DBH and c-Fos double-immunofluorescence staining in A2 region. Coronal sections showing A2m (middle rostro-caudal region of A2) and A2r (rostral extent of A2) from saline- or orexin-A-treated rats. Orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) significantly stimulates c-Fos expression in A2, but cells expressing immunoreactivity for both c-Fos and DBH were observed primarily in A2r. Schematic representations of coronal brain sections showing each region are presented at left, and distance (in mm) caudal to bregma is shown. Bar, 25 μm.

Fig. 3.

DBH and c-Fos double-immunofluorescence staining in C2 region. Coronal sections from C2 (caudal and medial parts) from saline- or orexin-A-treated rats are shown. In caudal C2, orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) significantly stimulated c-Fos expression primarily in non-DBH cells. Schematic representations of coronal brain sections showing each region are presented at left, and distance (in mm) caudal to bregma is shown. Bar = 25 μm.

Fig. 4.

DBH and c-Fos double-immunofluorescence staining in A5-A7 regions. Coronal sections at A7, A6, and ventral A5 from saline- and orexin-A-treated rats are shown. Orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) significantly stimulates c-Fos expression in DBH-positive cells in A5 and A6, and in non-DBH cells in the A7 region. Schematic representations of coronal brain sections showing each region are presented at left, and distance (in mm) caudal to bregma is shown. Bar, 25 μm.

Microinjections of orexin-A into A1/C1 stimulated food intake.

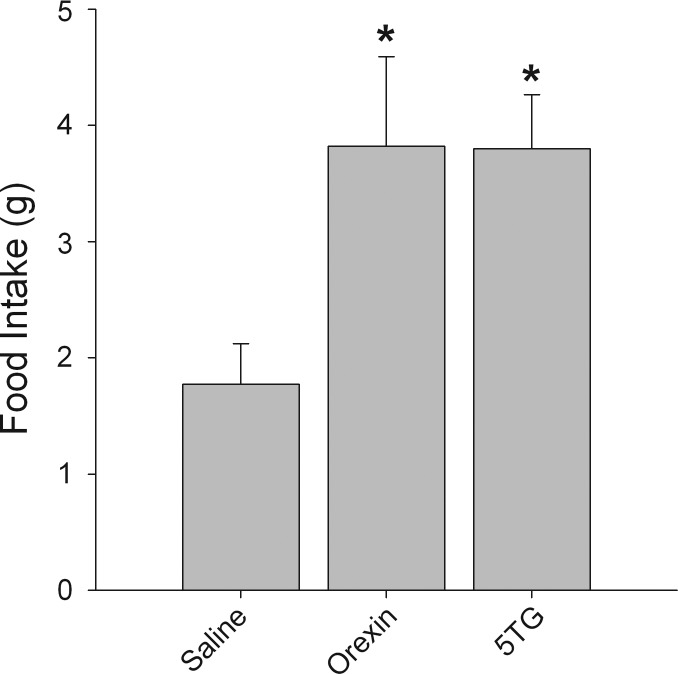

To determine whether orexin-A innervation stimulates feeding by activating neurons in A1/C1 area, a dose of orexin-A (67 pmol/200 nl), lower than our ventricular dose, was bilaterally injected directly into the A1/C1 area. As shown in Fig. 5, food intake was significantly enhanced by local orexin-A injection (P < 0.05; n = 9). In the same rats, 5TG injection (24 μg/200 nl) into A1/C1 also enhanced feeding (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effects of A1/C1 orexin-A injection on food intake. Orexin-A (67 pmol/200 nl/side), 5-thio-D-glucose (5TG; 24 μg/200 nl/side), or vehicle solution saline (200 nl/side) was injected directly into A1/C1, bilaterally. Both orexin-A and 5TG increased 4-h food intake after the injection. *P < 0.05, vs. saline treatment (n = 9 rats for each treatment).

DSAP abolished feeding induced by 4V and LV orexin-A.

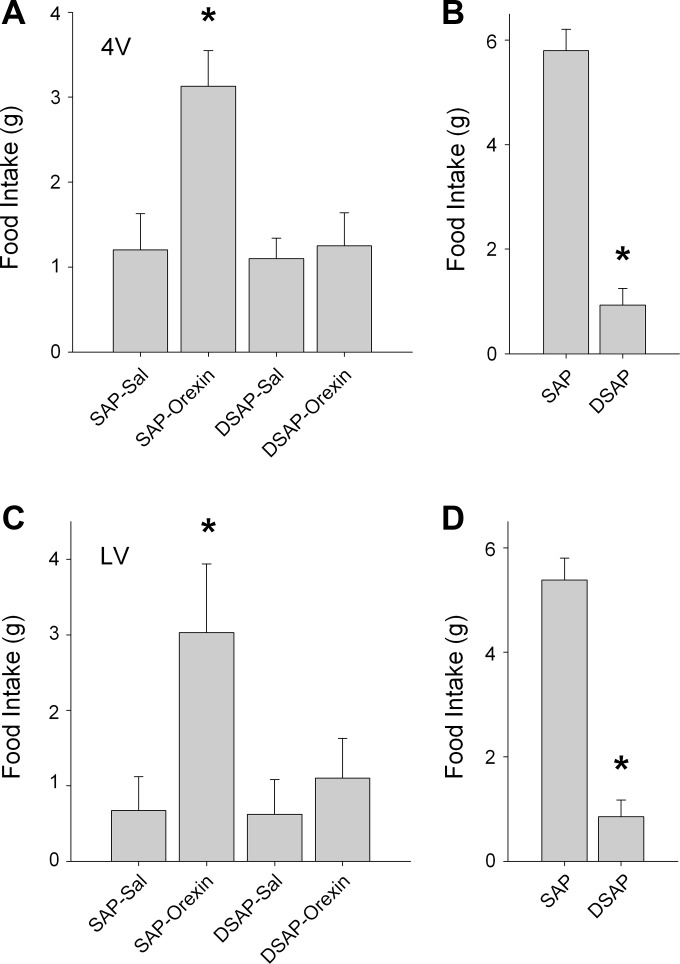

Effects of 4V or LV orexin-A on feeding were investigated in DSAP-lesioned and SAP control rats. Orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat), injected into 4V in SAP rats (n = 8), stimulated feeding significantly compared with intake after saline injection (P < 0.01; Fig. 6A). However, orexin-A did not increase feeding in DSAP rats (P > 0.7; n = 8). Glucoprivic feeding induced by 2DG (200 mg/kg sc) was also abolished in DSAP rats compared with SAP rats (P < 0.001: Fig. 6B), confirming the DSAP lesion. Similarly, orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) injected into LV stimulated feeding in SAP rats (n = 5) above their intake after saline injection (P < 0.05; Fig. 6C), and this response was abolished in DSAP rats (P > 0.5; n = 6). Lesions of hindbrain catecholamine neurons in LV-DSAP rats were confirmed by 2DG-induced glucoprivic feeding (P < 0.001; Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Effects of orexin-A on feeding in unconjugated saporin (SAP)/anti-DBH conjugated to saporin (DSAP) rats. A: orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) or saline (Sal) was injected into 4V in SAP or DSAP rats, and 4-h food intake after the injection is shown; n = 8 rats per group. *P < 0.01, vs. SAP Sal control. B: DSAP-induced lesion of hindbrain catecholamine neurons of rats in A was confirmed by 2DG (200 mg/kg sc)-induced feeding, which was significantly reduced in DSAP rats. *P < 0.001, vs. SAP rats. C: orexin-A (0.5 nmol/rat) or Sal was injected into LV in SAP or DSAP rats. Food intake (4 h) after the injection is shown; n = 5 or 6 rats per group. *P < 0.05, vs. SAP Sal control. D: lesion of hindbrain catecholamine neurons of rats in C by DSAP was confirmed by 2DG-induced glucoprivic feeding. *P < 0.001, vs. SAP rats.

At the end of the experimentation, DBH cells in each hindbrain catecholamine region were counted. As shown in Table 2, PVH DSAP treatment resulted in significant loss of DBH-ir neurons in the ventrolateral cell groups, A1, A1/C1, and C1m (Table 2), and also in the dorsomedial cell groups, A2, C2, and C3 (not shown) in both 4V- or LV-implanted rats (Ps < 0.001; n = 5–8). DBH immunoreactivity was not reduced in A5 and A7 (not shown) and was only slightly reduced in C1r of DSAP-treated rats, since these cell groups do not project to the PVH DSAP injection site. Loss of neurons in A6 was apparent, but because of the density of DBH neurons in A6, cell loss was not quantified.

Table 2.

Numbers of DBH-positive cells in hindbrain regions in paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus SAP and DSAP rats

| Group |

4V |

LV |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region/Treatment | SAP | DSAP | SAP | DSAP |

| n | 8 | 8 | 5 | 6 |

| A1 | 20.5 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6* | 17.6 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.4* |

| A1/C1 | 25.6 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 0.8* | 22.6 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3* |

| C1m | 23.9 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.4* | 21.5 ± 0.8 | 6.0 ± 0.7* |

| C1r | 26.9 ± 1.3 | 22.5 ± 0.9# | 24.4 ± 1.7 | 20.8 ± 1.0 |

| A2m | 32.2 ± 1.1 | 13.4 ± 1.2* | 34.3 ± 1.8 | 12.2 ± 1.1* |

| A2r | 43.6 ± 1.7 | 17.9 ± 1.6* | 44.2 ± 1.6 | 21.2 ± 1.8* |

| C2c | 30.5 ± 1.6 | 20.5 ± 1.2* | 27.4 ± 1.7 | 19.8 ± 1.3* |

| C2m | 24.5 ± 1.1 | 15.1 ± 0.7* | 19.9 ± 1.0 | 15.8 ± 0.9# |

Values are means ± SE. Numbers of DBH-positive cells per side in each hindbrain region in paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus SAP and DSAP rats, implanted with a 4V or lateral ventricular (LV) cannula, are shown. Numbers were averages for each region (counted 2 or 3 sections per rat for each region).

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 vs. SAP rats.

DISCUSSION

Abundant evidence over the past four decades has shown that the hindbrain catecholamines, NE and E, potently stimulate food intake (6, 22, 24, 31, 38, 41, 44). Previous work (59) also has shown that 4V injection of orexin-A stimulates feeding, that orexin terminals are present in the vicinity of hindbrain catecholamine cell groups, and that ventricular administration of orexin-A increases c-Fos expression in catecholamine neurons. Our c-Fos experiments confirm and extend this previous work showing that significant numbers of catecholamine neurons are activated by 4V administration of orexin-A. We observed orexin-A-induced c-Fos expression in all NE and E cell groups except A7, with regional differences in the prevalence of c-Fos/DBH coexpression within each group. With the exception of A6, which was highly activated by orexin-A, the cell groups with the greatest proportion of orexin-A-activated DBH neurons were A1 and C1 in the ventrolateral medulla. In the A1/C1 and C1m regions, ∼40% of DBH-positive neurons were activated by orexin-A and ∼70% of c-Fos-ir neurons were also DBH positive. Fewer DBH-ir neurons (14%) in C1r were activated.

Although results showing that activation of catecholamine neurons by ventricular orexin-A injection provide confirming anatomical evidence that catecholamine neurons constitute a potential hindbrain substrate for orexin-induced stimulation of feeding, they do not in themselves reveal the pertinent sites of orexin action specifically for the feeding response. However, the fact that injection of orexin-A directly into the A1-C1m region was effective in stimulating a robust feeding response, at a much lower dose than used for 4V or LV injections, identifies ventrolateral medullary catecholamine neurons as key contributors to orexin-induced feeding. In addition, these results implicate orexin neurons specifically (but not exclusively) in glucoregulatory feeding. Our previous work has demonstrated a critical role for the A1/C1 catecholamine neurons in glucoprivic feeding. Localized nanoinjections of 5TG in this area stimulate food intake (1, 42), glucoprivation increases expression of both neuropeptide Y (NPY) (25) and DBH genes (27) in this region, and simultaneous silencing of coexpressed genes for NPY and DBH at this site reversibly suppresses glucoprivic feeding (26). Moreover, the possibility that orexin neurons are involved in glucoregulatory feeding is enhanced by their known responsiveness to glucose availability (7, 8, 18). However, the fact that destruction of hindbrain catecholamine neurons abolishes the glucoprivic control of feeding does not preclude orexin-catecholamine interaction in nonglucoregulatory controls of feeding in intact rats. Our PVH DSAP injection damages a large proportion of the total population of both dorsomedial and ventrolateral medullary catecholamine neurons with hypothalamic projections (40, 43), some of which mediate nonglucoregulatory feeding responses (20).

In the present experiments, we destroyed catecholamine neurons with projections to the hypothalamus by injecting DSAP, the retrogradely transported saporin conjugate that selectively targets DBH-expressing neurons (4, 56), into the PVH. We report here that this treatment abolished feeding responses to both LV and 4V orexin-A injections, indicating that hindbrain catecholamine neurons projecting to the hypothalamus are not only involved in but are required components of the circuitry for orexin-induced feeding. Loss of orexin-A-induced feeding in DSAP-lesioned rats is not likely to be due to nonspecific behavioral disruption arising from the lesion. We have shown previously that the lesion produced by hypothalamic DSAP injection abolishes glucoregulatory responses, including loss of feeding responses to systemic and central glucoprivation, but does not produce nonspecific behavioral impairment. Under normal laboratory conditions, DSAP-treated rats remain healthy, maintain normal body weights, increase their food intake in response to overnight food deprivation and lipoprivic challenge, and have normal daily caloric intake (40, 43) and normal circadian distribution of feeding behavior (unpublished). Similarly, the PVH injection of DSAP would not have damaged orexin neurons or their terminals nonspecifically. In previous work, we reported that injection of DSAP into the PVH did not damage CRH neurons located in the PVH injection site or impair their function in response to nonglucoprivic stimulation (43).

Although orexin-A activates catecholamine neurons and stimulates food intake, and may facilitate aspects of glucoprivic feeding, orexinergic input is not required for activation of catecholamine neurons involved in feeding responses to glucoprivation. Localized glucoprivation induced by nanoliter injections of the glucoprivic agent, 5TG, into hindbrain catecholamine cell groups stimulates feeding (1, 42). Although local glucoprivation could conceivably increase release of orexins from terminals at a hindbrain injection site in intact rats, it has also been shown that unanesthetized chronic decerebrate rats increase consummatory feeding responses to systemic glucoprivation (12, 16). In this chronic decerebrate preparation, orexin terminals in the hindbrain would be eliminated. In addition, LV administration of 5TG is ineffective in stimulating feeding when confined to the rostral ventricular space by an acute aqueduct plug, a preparation that would not be expected to interfere with activation of orexin neurons by 5TG or with orexin projections to the hindbrain (39). In contrast, 4V injections of 5TG remain effective in aqueduct-occluded animals (39). Thus, it seems clear that while orexin neurons may be a sufficient source, they are not the only source of catecholamine activation leading to food intake and are not required for activation of these neurons in response to glucoprivation.

It is interesting that orexin neurons are not only able to activate catecholamine subpopulations but are themselves targeted and activated by catecholamine neurons, indicating a reciprocal relationship between these cell types. Catecholamine neurons from the A1 and C1 cell group project to orexinergic areas of the hypothalamus (9, 20), and the majority of these express phenethanolamine N-methyl transferase (PNMT) (5). Recent work using neuron-selective viral tracing, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy reports that these PNMT-expressing neurons (i.e., C1 neurons) form excitatory synaptic contacts (predominantly asymmetric synapses) with orexin cell bodies and dendrites (5). PNMT synaptic profiles in orexinergic sites also contain a predominance of small, clear synaptic vesicles typical of those that release glutamate, and C1 neurons are known to express vesicular glutamate transporter 2-ir (50). Therefore, it is possible that (at least under some conditions) glutamate is the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter at catecholaminergic synapses on orexin neurons.

In addition to glutamate, rostrally projecting catecholamine neurons in the A1/C1 cell group also coexpress NPY (15, 47), a peptide that is potently orexigenic when injected into the cerebroventricles (49, 52, 57) and into various hypothalamic sites, including the rostral perifornical hypothalamus (48). In addition, simultaneous blockade of Dbh and Npy in A1/C1 impairs the feeding response to systemic glucoprivation (26), suggesting that both NPY and catecholamines mediate orexigenic effects. However, the effects of NPY and catecholamines on orexin neurons themselves are complex. Inhibitory effects of NE, E, and NPY on orexin neurons have been demonstrated (17, 28, 58). This inhibition is puzzling in light of the increased c-Fos expression apparently arising from activation of catecholamine neurons in our experiment. This may reflect the differential modulation of orexin neuron activation state by physiological variables (such as glucoprivation), the receptor subtype that predominates at the particular sites of transmitter release, or the specific cotransmitter that predominates at this site and under the conditions tested. A reasonable explanation is that glutamate is the excitatory neurotransmitter released from catecholamine neurons that is responsible for activation of orexin neurons at this site, as discussed above. Clearly, additional work will be required to resolve this issue.

The dorsomedial medulla, which contains primary input and output sites for vagal sensory and motor neurons, respectively, contains catecholamine neurons comprising cell groups A2 and C2 and is associated with multiple controls of feeding and metabolism (19). Orexin fibers make close contact with catecholamine neurons in the dorsomedial medulla (59), and neurons in this area were also activated in our experiment following 4V injection of orexin-A, as described previously (59). We did not inject orexin directly into the NTS in this experiment. However, earlier work by Zheng et al. (59), by using a number of feeding paradigms, reported that injection of orexin-A into the NTS itself did not increase food intake. These investigators reported that orexin briefly stimulated intake of a high-fat diet, but the effect was significant only at 30 min, and higher doses suppressed food intake. Intake of 15% sucrose was not increased by NTS orexin injection. NTS orexin injections, however, were effective in increasing various autonomic responses that may have interfered with the feeding response. Alternatively, orexin terminals in the NTS may not be involved in food intake or may mediate suppression of food intake.

Perspectives and Significance.

It is clear from our results that orexin-A stimulates feeding and that hindbrain catecholamine neurons are a required substrate for the feeding response. The glucoprivic control of feeding is an important, but not the only, control of feeding and energy homeostasis that uses catecholamine neurons (37). Thus there are various ways in which the orexin and catecholamine neurons may influence food intake by their reciprocal interactions. The contribution of orexin neurons to glucoprivic feeding is a particularly interesting possibility given electrophysiological evidence revealing their seemingly unique glucose-sensing strategies (7, 8, 18) and the reciprocal innervation between orexin and catecholamine neurons that we show here to be a component of the feeding circuitry. A reasonable speculation that is consistent with their widespread innervation of the brain and spinal cord is that the role of orexin neurons in the glucoregulatory feeding is to coordinate anticipated and ongoing levels of arousal and activity with appropriate behavioral, metabolic, and autonomic adjustments (54, 55). Similarly, it is both reasonable and provocative to consider that the catecholaminergic glucoregulatory system, which appears to be organized for rapid and unconditional responses to acute glucose deficit, would be wired to activate an arousal system that facilitates these adjustments. On the basis of current data, mechanisms of cooperativity between these two widely projecting systems would appear to be a rich field for future studies of glucoregulatory circuitry, food intake, and autonomic controls.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service Grants DK-040498 and DK-081546 (to S. Ritter).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.-J.L. and S.R. conception and design of research; A.-J.L., Q.W., H.D., and R.W. performed experiments; A.-J.L. analyzed data; A.-J.L. and S.R. interpreted results of experiments; A.-J.L. prepared figures; A.-J.L. and S.R. drafted manuscript; A.-J.L. and S.R. edited and revised manuscript; A.-J.L., Q.W., H.D., R.W., and S.R. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew SF, Dinh TT, Ritter S. Localized glucoprivation of hindbrain sites elicits corticosterone and glucagon secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1792–R1798, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird JP, Choe A, Loveland JL, Beck J, Mahoney CE, Lord JS, Grigg LA. Orexin-A hyperphagia: hindbrain participation in consummatory feeding responses. Endocrinology 150: 1202–1216, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barson JR, Morganstern I, Leibowitz SF. Complementary roles of orexin and melanin-concentrating hormone in feeding behavior. Int J Endocrinol 2013: 983964, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blessing WW, Lappi DA, Wiley RG. Destruction of locus coeruleus neuronal perikarya after injection of anti-dopamine-B-hydroxylase immunotoxin into the olfactory bulb of the rat. Neurosci Lett 243: 85–88, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochorishvili G, Nguyen T, Coates MB, Viar KE, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. The orexinergic neurons receive synaptic input from C1 cells in rats. J Comp Neurol 522: 3834–3846, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth DA. Localization of the adrenergic feeding system in the rat diencephalon. Science 158: 515–517, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdakov D, Gerasimenko O, Verkhratsky A. Physiological changes in glucose differentially modulate the excitability of hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone and orexin neurons in situ. J Neurosci 25: 2429–2433, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdakov D, Gonzalez JA. Physiological functions of glucose-inhibited neurons. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 195: 71–78, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Card JP, Sved JC, Craig B, Raizada M, Vazquez J, Sved AF. Efferent projections of rat rostroventrolateral medulla C1 catecholamine neurons: implications for the central control of cardiovascular regulation. J Comp Neurol 499: 840–859, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi DL, Davis JF, Magrisso IJ, Fitzgerald ME, Lipton JW, Benoit SC. Orexin signaling in the paraventricular thalamic nucleus modulates mesolimbic dopamine and hedonic feeding in the rat. Neuroscience 210: 243–248, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS 2nd Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 322–327, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiRocco RJ, Grill HJ. The forebrain is not essential for sympathoadrenal hyperglycemic response to glucoprivation. Science 204: 1112–1114, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dube MG, Kalra SP, Kalra PS. Food intake elicited by central administration of orexins/hypocretins: identification of hypothalamic sites of action. Brain Res 842: 473–477, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards CM, Abusnana S, Sunter D, Murphy KG, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. The effect of the orexins on food intake: comparison with neuropeptide Y, melanin-concentrating hormone and galanin. J Endocrinol 160: R7–R12, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everitt BJ, Hokfelt T, Terenius L, Tatemoto K, Mutt V, Goldstein M. Differential co-existence of neuropeptide Y (NPY)-like immunoreactivity with catecholamines in the central nervous system of the rat. Neuroscience 11: 443–462, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn FW, Grill HJ. Insulin elicits ingestion in decerebrate rats. Science 221: 188–190, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu LY, Acuna-Goycolea C, van den Pol AN. Neuropeptide Y inhibits hypocretin/orexin neurons by multiple presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms: tonic depression of the hypothalamic arousal system. J Neurosci 24: 8741–8751, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez JA, Reimann F, Burdakov D. Dissociation between sensing and metabolism of glucose in sugar sensing neurones. J Physiol 587: 41–48, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grill HJ, Hayes MR. The nucleus tractus solitarius: a portal for visceral afferent signal processing, energy status assessment and integration of their combined effects on food intake. Int J Obes (Lond) 33, Suppl 1: S11–S15, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB. C1 neurons: the body's EMTs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R187–R204, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kay K, Parise EM, Lilly N, Williams DL. Hindbrain orexin 1 receptors influence palatable food intake, operant responding for food, and food-conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231: 419–427, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leibowitz SF. Adrenergic stimulation of the paraventricular nucleus and its effects on ingestive behavior as a function of drug dose and time of injection in the light-dark cycle. Brain Res Bull 3: 357–363, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leibowitz SF, Sladek C, Spencer L, Tempel D. Neuropeptide Y, epinephrine and norepinephrine in the paraventricular nucleus: stimulation of feeding and the release of corticosterone, vasopressin and glucose. Brain Res Bull 21: 905–912, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leibowitz SF, Weiss GF, Yee F, Tretter JB. Noradrenergic innervation of the paraventricular nucleus: specific role in control of carbohydrate ingestion. Brain Res Bull 14: 561–567, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li AJ, Ritter S. Glucoprivation increases expression of neuropeptide Y mRNA in hindbrain neurons that innervate the hypothalamus. Eur J Neurosci 19: 2147–2154, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT, Ritter S. Simultaneous silencing of Npy and Dbh expression in hindbrain A1/C1 catecholamine cells suppresses glucoprivic feeding. J Neurosci 29: 280–287, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li AJ, Wang Q, Ritter S. Differential responsiveness of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase gene expression to glucoprivation in different catecholamine cell groups. Endocrinology 147: 3428–3434, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, van den Pol AN. Direct and indirect inhibition by catecholamines of hypocretin/orexin neurons. J Neurosci 25: 173–183, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madden CJ, Stocker SD, Sved AF. Attenuation of homeostatic responses to hypotension and glucoprivation after destruction of catecholaminergic rostral ventrolateral medulla neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R751–R759, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 435: 6–25, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews JW, Booth DA, Stolerman IP. Factors influencing feeding elicited by intracranial noradrenaline in rats. Brain Res 141: 119–128, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellen NM, Thoby-Brisson M. Respiratory circuits: development, function and models. Curr Opin Neurobiol 22: 676–685, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nambu T, Sakurai T, Mizukami K, Hosoya Y, Yanagisawa M, Goto K. Distribution of orexin neurons in the adult rat brain. Brain Res 827: 243–260, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parise EM, Lilly N, Kay K, Dossat AM, Seth R, Overton JM, Williams DL. Evidence for the role of hindbrain orexin-1 receptors in the control of meal size. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R1692–R1699, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci 18: 9996–10015, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. J Neurosci 23: 10084–10092, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter RC, Epstein AN. Control of meal size by central noradrenergic action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72: 3740–3743, 1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritter RC, Slusser PG, Stone S. Glucoreceptors controlling feeding and blood glucose: location in the hindbrain. Science 213: 451–452, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritter S, Bugarith K, Dinh TT. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholamine subgroups produces selective impairment of glucoregulatory responses and neuronal activation. J Comp Neurol 432: 197–216, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Li AJ. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons control multiple glucoregulatory responses. Physiol Behav 89: 490–500, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Zhang Y. Localization of hindbrain glucoreceptive sites controlling food intake and blood glucose. Brain Res 856: 37–47, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritter S, Watts AG, Dinh TT, Sanchez-Watts G, Pedrow C. Immunotoxin lesion of hypothalamically projecting norepinephrine and epinephrine neurons differentially affects circadian and stressor-stimulated corticosterone secretion. Endocrinology 144: 1357–1367, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritter S, Wise D, Stein L. Neurochemical regulation of feeding in the rat: facilitation by alpha-noradrenergic, but not dopaminergic, receptor stimulants. J Comp Physiol Psychol 88: 778–784, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakurai T. The neural circuit of orexin (hypocretin): maintaining sleep and wakefulness. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 171–181, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92: 573–585, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Grzanna R, Howe PR, Bloom SR, Polak JM. Colocalization of neuropeptide Y immunoreactivity in brainstem catecholaminergic neurons that project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol 241: 138–153, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stanley BG, Magdalin W, Seirafi A, Thomas WJ, Leibowitz SF. The perifornical area: the major focus of (a) patchily distributed hypothalamic neuropeptide Y-sensitive feeding system(s). Brain Res 604: 304–317, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steinman JL, Gunion MW, Morley JE. Forebrain and hindbrain involvement of neuropeptide Y in ingestive behaviors of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 47: 207–214, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stornetta RL, Sevigny CP, Schreihofer AM, Rosin DL, Guyenet PG. Vesicular glutamate transporter DNPI/VGLUT2 is expressed by both C1 adrenergic and nonaminergic presympathetic vasomotor neurons of the rat medulla. J Comp Neurol 444: 207–220, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sweet DC, Levine AS, Billington CJ, Kotz CM. Feeding response to central orexins. Brain Res 821: 535–538, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor K, Lester E, Hudson B, Ritter S. Hypothalamic and hindbrain NPY, AGRP and NE increase consummatory feeding responses. Physiol Behav 90: 744–750, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Guan XM. Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS Lett 438: 71–75, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsuneki H, Wada T, Sasaoka T. Role of orexin in the central regulation of glucose and energy homeostasis. Endocr J 59: 365–374, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Venner A, Karnani MM, Gonzalez JA, Jensen LT, Fugger L, Burdakov D. Orexin neurons as conditional glucosensors: paradoxical regulation of sugar sensing by intracellular fuels. J Physiol 589: 5701–5708, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wrenn CC, Picklo MJ, Lappi DA, Robertson D, Wiley RG. Central noradrenergic lesioning using anti-DBH-saporin: anatomical findings. Brain Res 740: 175–184, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu B, Li BH, Rowland NE, Kalra SP. Neuropeptide Y injection into the fourth cerebroventricle stimulates c-Fos expression in the paraventricular nucleus and other nuclei in the forebrain: effect of food consumption. Brain Res 698: 227–231, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamanaka A, Muraki Y, Ichiki K, Tsujino N, Kilduff TS, Goto K, Sakurai T. Orexin neurons are directly and indirectly regulated by catecholamines in a complex manner. J Neurophysiol 96: 284–298, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng H, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Orexin-A projections to the caudal medulla and orexin-induced c-Fos expression, food intake, and autonomic function. J Comp Neurol 485: 127–142, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Y, Yamanaka A, Kunii K, Tsujino N, Goto K, Sakurai T. Orexin-mediated feeding behavior involves both leptin-sensitive and -insensitive pathways. Physiol Behav 77: 251–257, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]