Abstract

During the last decades, the study of cell behavior was largely accomplished in uncoated or extracellular matrix (ECM)-coated plastic dishes. To date, considerable cell biological efforts have tried to model in vitro the natural microenvironment found in vivo. For the lung, explants cultured ex vivo as lung tissue cultures (LTCs) provide a three-dimensional (3D) tissue model containing all cells in their natural microenvironment. Techniques for assessing the dynamic live interaction between ECM and cellular tissue components, however, are still missing. Here, we describe specific multidimensional immunolabeling of living 3D-LTCs, derived from healthy and fibrotic mouse lungs, as well as patient-derived 3D-LTCs, and concomitant real-time four-dimensional multichannel imaging thereof. This approach allowed the evaluation of dynamic interactions between mesenchymal cells and macrophages with their ECM. Furthermore, fibroblasts transiently expressing focal adhesions markers incorporated into the 3D-LTCs, paving new ways for studying the dynamic interaction between cellular adhesions and their natural-derived ECM. A novel protein transfer technology (FuseIt/Ibidi) shuttled fluorescently labeled α-smooth muscle actin antibodies into the native cells of living 3D-LTCs, enabling live monitoring of α-smooth muscle actin-positive stress fibers in native tissue myofibroblasts residing in fibrotic lesions of 3D-LTCs. Finally, this technique can be applied to healthy and diseased human lung tissue, as well as to adherent cells in conventional two-dimensional cell culture. This novel method will provide valuable new insights into the dynamics of ECM (patho)biology, studying in detail the interaction between ECM and cellular tissue components in their natural microenvironment.

Keywords: tissue-immunolabeling, three-dimensional ex vivo lung tissue cultures, 4D confocal imaging

in the last decades, the study of mesenchymal cell behavior was largely accomplished in flat, two-dimensional (2D) environments, such as uncoated or extracellular matrix (ECM)-coated plastic dishes. In 2D cell culture systems, cells such as fibroblasts develop an artificial polarity between their ventral and dorsal surface, displaying a predominantly flat morphology. Here, prominent cell-matrix adhesions and massive F-actin-rich stress fibers represent cellular features that are usually not found in the native environment of living tissue. Therefore, there has been a considerable effort in cell biology to utilize three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models from synthetic and natural materials intending to mimic in vitro the natural in vivo environment (1, 4, 5, 12, 20, 25, 29, 35). Depending on the 3D cell culture model, these studies have revealed substantial differences with respect to cell behavior, cell morphology, cytoskeletal structures, and signaling events, compared with cells cultured on 2D cell culture dishes (4, 5, 9, 13, 34). Various 3D cell culture models, such as Matrigel, collagen-1 gels, and cell-derived ECM matrices have emerged and been intensively used over the last years (5, 6, 9, 11). These models, although culturing cells in a spatial 3D context, still represent only an approximation of the real tissue's biochemical, structural, and biomechanical status.

The ex vivo cultured precision-cut tissue slices (PCTS) derived from various organs and species provide an arising and exciting new 3D cell culture technology to study cell behavior in its native microenvironment. Up until now, vital PCTS from human and rodent organs, especially from the liver, intestine, and the lung, were predominantly used as an ex vivo tool in physiological or pharmacotoxicological studies (7, 8, 15, 24, 28, 31). PCTS can be derived from normal and diseased human tissues, as well as from various mouse disease models, such as the bleomycin mouse model that mimics fibrosis in the lung. Thus disease-derived tissues can be directly evaluated ex vivo in a culture dish. This includes the study of single cells and cell layers, as well as the interaction of cells within and with their surrounding ECM.

Assessing the dynamics of tissue compartments in living PCTS, as well as subcellular structures, requires the technology to specifically stain cells or proteins, and subsequent imaging by four-dimensional (4D) (3D stacks over time) confocal time-lapse microscopy. Vital and membrane-permeable dyes that are of use for live-cell imaging in conventional 2D cell culture can readily be applied to ex vivo tissue slices (19). However, techniques to study the dynamic interaction of cells and their surrounding ECM by 4D time-lapse microscopy are missing. For fixed tissue and cells, immunofluorescence (IF)-based labeling techniques are important tools in visualizing and gaining biological information about the spatial relationship of cells and proteins, localization patterns, and expression levels. Here, by taking advantage of IF, we present a novel and valuable toolbox that comprises the multidimensional immunolabeling of living lung tissue slices with specific antibodies (Abs) against cell surface markers, ECM, or cytoskeletal proteins, and subsequent 4D confocal imaging of stained PCTS in low- and high-optical resolution. Using this approach, we investigated the interplay of cells with their surrounding ECM components on the cellular and subcellular level using 3D ex vivo lung tissue cultures (LTCs) (30). Here, we focused on 3D-LTCs derived mainly from normal and diseased murine, but also human lungs. We reason that these tools are widely applicable in cell biology, as these will work in most 3D cell culture settings, as well as in conventional 2D cell culture systems.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals.

Pathogen-free female C57Bl/6-N mice (C57BL/6NCrl, Charles River) between the ages of 8 and 12 wk were used. Mice were housed with water and food ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of the Helmholtz-Center Munich and approved by the Regierungspräsidium Oberbayern, Germany (project no. 55.2-1-54-2532-168-09).

Animal model of experimental fibrosis.

For the induction of lung fibrosis, mice were subjected to intratracheal bleomycin instillation. Bleomycin sulfate (Almirall, Barcelona, Spain) was dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline and applied using the Micro-Sprayer Aerosolizer, model IA-1C (Penn-Century, Wyndmoor, PA), as a single dose of 0.08 mg in 50 μl solution per animal (3 U/kg body wt). Control mice were treated with 50 μl PBS. Mice were killed at day 14 after instillation for generation of 3D-LTC.

Human tissue.

The experiments with human tissue were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ludwig-Maximillian University Munich, Germany (project no. 455-12). All samples were provided by the Asklepios Biobank for Lung Diseases, Gauting, Germany (project no. 333-10). Written, informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Tumor or tumor-free tissue from patients that underwent lung tumor resection was used.

Generation of human and murine 3D ex vivo LTCs (3D-LTCs).

For the murine 3D-LTCs, healthy and fibrotic mice were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (Bela-Pharm) and xylazinhydrochloride (CP-Pharma). After intubation and dissection of the diaphragm, lungs were flushed via the heart with sterile sodium chloride, and a bronchoalveolar lavage was taken (2 × 500 μl sterile PBS). Using a syringe pump, lungs got infiltrated with warm, low-melting agarose (2 wt%, Sigma, Germany, kept at 40°C) in sterile cultivation medium (DMEM/F12, Gibco, Germany, supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin and amphotericin B; both Sigma). The trachea was closed with a thread to keep the agarose inside the lung. Afterwards, the lung was excised, transferred into a tube with cultivation medium, and cooled on ice for 10 min, to allow gelling of the agarose. The lobes were separated and cut with a vibratome (Hyrax V55, Zeiss, Germany) to a thickness of 300 μm. The 3D-LTCs were cultivated for a maximum of 5 days in sterile conditions. The viability and functionality of the 3D-LTCs was extensively tested in our laboratory's recent publication (30), showing a solid viability and functionality up to 5 days in culture. Here, all experiments with 3D-LTCs were performed with lung slices between days 1 and 5. For the patient-derived 3D-LTCs, lung segments from non-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients without tumor infiltration were cannulized via the bronchus and filled with warm agarose immediately after excision. Lung segments were cooled on ice for 30 min to allow gelling of the agarose (3 wt%), cut to a thickness of 500 μm, and cultivated for a maximum of 5 days. Tumor segments were cut the same way after embedding in agarose.

Abs.

For live fluorescence immunolabeling, the following primary and secondary Abs were used: 1) primary: rabbit monoclonal Ab to caveolin-1 (no. 3267, Cell Signaling, 1:100), rat monoclonal Ab to Mac-3 (no. 550292, BD, 1:100), mouse monoclonal Ab to α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) conjugated with Cy3 (C6198, clone 1A4, Sigma, 1:100), and rabbit polyclonal Abs to fibronectin (H-200, Santa Cruz, 1:100), galectin-3 (sc-20157, Santa Cruz, 1:100), and collagen type I (no. 600-401-103-01, Rockland, 1:100); and 2) secondary: donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor-488 (Invitrogen, 1:500), donkey anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor-568 (Invitrogen, 1:500).

Live fluorescence immunolabeling of vital tissues and cells.

For fluorescence immunolabeling, the tissue or cells were incubated with the primary Ab in the appropriate dilution in prewarmed 200–400 μl DMEM/Ham's F-12 (catalog no. E15-813, PAA) medium containing 10% FBS for 16 h by using standard cell-culture conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C). Tissue staining was accomplished in 24-well plates (TPP Techno Plastic Products) containing the 3D-LTCs. During the staining procedure, the 24-well plate was sealed with a parafilm to prevent rapid evaporation of the medium. Staining of adherent cells was accomplished in 35-mm CellView cell culture dishes with a glass bottom (Greiner BioOne). Subsequently, the tissue or cells were washed once in DMEM/Ham's F-12 and incubated with the secondary Ab in prewarmed 500- to 1,000-μl DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% FBS for a period of 2 h by using standard cell-culture conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C). Finally, the tissue or cells were washed once in warm DMEM/Ham's F-12 and incubated in fresh and prewarmed DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% FBS. We found that additional washing steps did not further improve the outcome of the staining quality. The nuclear staining of cells or tissue was accomplished by incubation with HOECHST (bisBenzimide H 33342 trihydrochloride, Sigma, 1:200), along with the secondary Ab as mentioned above. Whole cells of 3D-LTCs were stained with 5 μM of the CellTracker Red CMTPX (catalog no. C34552, Molecular Probes).

Cell culture, transient transfections, cDNA constructs, and applying transfected cells to 3D-LTCs.

Mouse lung fibroblasts MLg (MLg 2908) were purchased from ATCC (CCL-206) and cultivated in DMEM/Ham's F-12 (catalog no. E15-813, PAA) medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were cultivated and passaged at standard conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C) and were not used at passage numbers higher than 15. Cells were transiently transfected in DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% FBS using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in a six-well format, according to the manufacturer's manual. Experiments were carried out 16–24 h after transfection. The α-actinin-1-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) cDNA construct (pGB9) encoding fusion protein was generated by subcloning the human α-actinin-1 cDNA from a pGEX-4T-1 via EcoR I sites into a pEGFP-N2 (Clontech) vector. The original α-actinin-1-pGEX-4T-1 plasmid was a generous gift of Dr. Kristina Djinovic-Carugo (Max F. Perutz Laboratories, Vienna, Austria). The generation of EGFP-plectin 1f (P1f)-8 was reported before (3), and the EGFP-vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) was a generous gift of M. Gimona (University of Salzburg, Austria). The transfected cells were trypsinized, resuspended in fresh cell culture medium, and incubated in a rolling fashion together with native 3D-LTCs in a 2-ml Eppendorf tube without the plastic lid, but sealed with parafilm for 16 h. Next, the 3D-LTCs were transferred to 24-well plates and either stained for ECM proteins, or directly used for microscopy.

Transfer of Abs into 2D fibroblasts and cells of tissue slices.

The transfer of a mouse monoclonal Ab to α-SMA conjugated with Cy3 (C6198, clone 1A4, Sigma) was accomplished by utilizing the Fuse-It-P membrane fusion system (catalog no. 60220, Ibidi). The reagent, which transfers various molecules and particles via liposomal carriers into mammalian cells by membrane fusion, was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. In short, 10–20 μg of the α-SMA-Cy3 Ab in 40 μl HEPES buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) were added to the lyophilized Fuse-It-P reagent and thoroughly resuspended and mixed. The mixture was sonicated for 10 min at room temperature. Then the fusogenic mixture was filled up with 60 μl HEPES buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) to a volume of 100 μl. Ten microliters of this mixture were diluted in 500 μl of sterile and prewarmed 1 × PBS buffer. After the culture medium was removed, the cells or lung tissue slices were incubated with 300–500 μl of the fusogenic mixture for 5 and 15 min at 37°C, respectively. Finally, the fusogenic mixture was replaced by fresh cell culture medium.

Tissue imaging chamber.

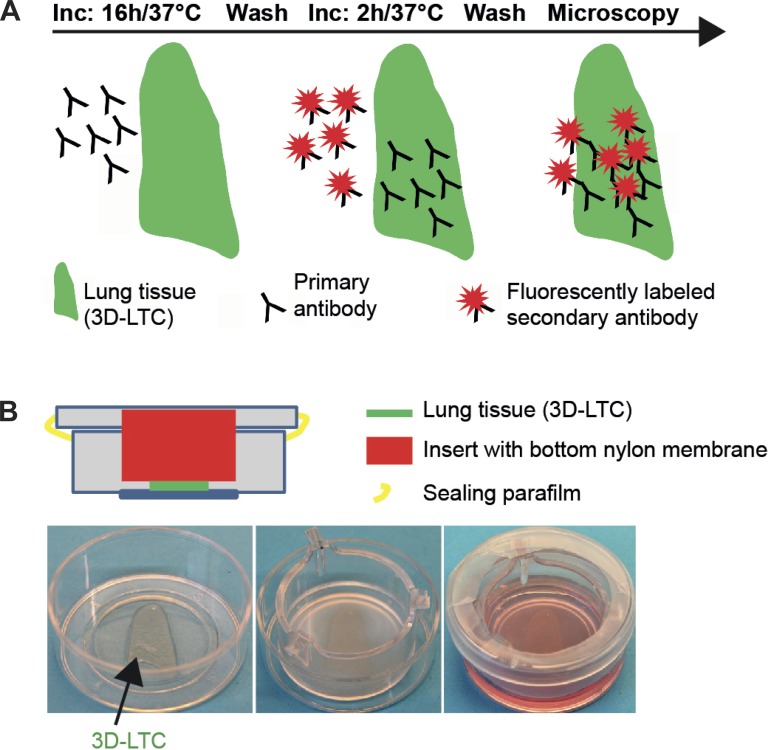

To keep the lung slices in place and in focus for 4D short- and long-term time-lapse imaging, we invented sealed tissue imaging chamber with an optical window for access by the microscope objectives. As shown in Fig. 1B, the living 3D-LTCs were taken out of the medium by using a pair of forceps and put in the middle part of the glass bottomed 35 mm CellView cell culture dish (Greiner BioOne). Next, on top of the 3D-LTCs, we placed the bottom nylon side of a tissue culture insert for six-well plates (ThinCerts, 8 μm pore size, Greiner Bio-One). The nylon side of the tissue culture insert touches the 3D-LTCs, but does not squash it. The bottom rim of the tissue culture inserts directly touches the plastic bottom of the CellView cell culture dish, leaving a small gap between the nylon bottom of the tissue culture insert and the glass bottom of the CellView cell culture dish. This gap was filled with 1 ml prewarmed DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% FBS by using a 1-ml blue Eppendorf tip and pipette. Here it is crucial that the blue Eppendorf tip directly touches the upper nylon side of the tissue culture insert, and the medium slowly fills the gap between the nylon bottom of the tissue culture insert and the glass bottom of the CellView cell culture dish without leaving any air bubbles behind. When all of the air is replaced by the medium, additional medium (2–3 ml) can be added to the inner side of the tissue culture insert. Finally the lid of the CellView cell culture dish was placed directly on top of the tissue culture insert and tightly sealed with parafilm. Next, before being taken to the microscope, the imaging chamber was put for 1 h into an incubator at standard conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C). During that time, gravity leveled out the different liquid levels between the inner and outer enclosures of the tissue imaging chamber.

Fig. 1.

Immunolabeling of live three-dimensional (3D)-lung tissue cultures (LTCs) and tissue imaging chamber. A: scheme depicting the staining procedure for the indirect immunolabeling of 3D-LTCs by sequentially adding the primary and the fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. B: to avoid spatial and focal drift, the vital 3D-LTCs (300 μm thick) were secured between the nylon mesh (pore size of 8 μm) of a cell culture insert and the glass coverslip sitting at the bottom of a CellView tissue culture imaging dish.

Confocal live tissue imaging.

Confocal time-lapse microscopy was implemented on an LSM710 system (Carl Zeiss) containing an inverted AxioObserver.Z1 stand equipped with phase-contrast and epi-illumination optics and operated by ZEN2009 software (Carl Zeiss). Tissue or cells were kept in DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% FBS and 15 mM HEPES during the whole period of observation. The tissue imaging chamber containing the 3D-LTCs or cells was placed in a PM S1 incubator chamber (Carl Zeiss) and kept at 37°C. Time-lapse images in various intervals were acquired by using the following objective lenses: EC Plan-Neofluar DICI ×10/0.3 numerical aperture (NA) (Carl Zeiss), LD C-Apochromat ×40/1.1 NA water objective lens (Carl Zeiss), and LCI PLN-NEOF DICIII ×63/1.30 NA water objective lens (Carl Zeiss). Z-stacks were taken according to the thickness of the 3D-LTCs and were ranging between 150 and 300 μm.

Image analysis, quantification, and statistical analysis.

The confocal 4D data sets were either maximum intensity projected in the ZEN2009 software (Carl Zeiss) or imported into Imaris 7.6.5 or 8.0.0 software (Bitplane). Within the Imaris software, the confocal 4D data sets were either volume or surface rendered and exported either as time-lapse movies or figures. For measuring the staining stability over time, we quantified the average intensity of each frame (1 frame per 2 h over a period of 48 h) of a maximum intensity projected z-stack by using the Zen 2012 blue edition (Carl Zeiss). The quantification of the collagen-1 content was performed by measuring the average intensity of a maximum intensity projected z-stack by using the Zen 2012 blue edition (Carl Zeiss), comparing regions of interests (ROIs) of 10 healthy vs. 10 fibrotic 3D-LTCs. The number of Mac-3 positive cells was assessed by applying the spot detection algorithm of the Imaris 8.0.0 software (Bitplane) on a maximum intensity projected z-stack, comparing ROIs of 10 healthy vs. 10 fibrotic 3D-LTCs. The migration speed of Mac-3 positive cells was measured by applying the spot detection algorithm of the Imaris 8.0.0 software (Bitplane) on a maximum-intensity projected z-stack of a time lapse (1 frame per 20 min over a period of 16 h) and subsequent software-based automatic spot-tracking in Imaris 8.0.0 (Bitplane). Here, two to three ROIs of five healthy and five fibrotic 3D-LTCs were compared. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by using unpaired and paired t-tests (two-tailed) in GraphPad Prism4 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Immunolabeling of 3D ex vivo LTCs (3D-LTCs) can be accomplished with off-the-shelf Abs, either by direct or indirect IF techniques. As depicted in Fig. 1A, the indirect IF labeling of vital 3D-LTCs was accomplished by applying the primary Ab diluted in 10% growth medium to 3D-LTCs at standard culture conditions for 16 h. Subsequently, the secondary fluorescently conjugated Abs were added to the medium containing the primary Abs. After an incubation time of 2 h, the 3D-LTCs were washed in fresh cultivation medium, removing all unbound Abs. Similar to IF staining protocols of fixed cells or tissue, the indirect IF staining of living tissue offers all the advantages in flexibility and sensitivity, whereas well-known disadvantages of indirect IF, such as high background or complexity in the staining protocol, were not a major limitation in our experiments. Moreover, staining live 3D-LTCs by indirect IF mostly outperformed the use of self-labeled primary Abs. As Abs cannot move across cellular membranes per se, immunolabeling of living tissue results in the detection of antigens found within the ECM or on the cell surface; yet it is crucial that the primary Ab recognizes the native epitope of its antigen.

Imaging of immunolabeled tissue slices presents challenges with respect to thickness (300 μm) and focal stability. Since the 3D-LTCs floated in culture medium, they had to be mechanically fixed for imaging to avoid spatial drifting. Thus we immobilized the 3D-LTCs between the nylon mesh (8-μm pore size) of a cell culture insert and the glass coverslip sitting at the bottom of a CellView tissue culture imaging dish (Fig. 1B). The glass coverslip of the tissue imaging chamber provided the appropriate optical window for the microscope's objective to acquire images with high-resolution lenses. The growth medium was applied straight through the nylon mesh of the cell culture insert. Finally, the lid of the imaging chamber was sealed with parafilm. This construction kept the 3D-LTCs in place and focus during confocal 4D imaging, even during long-term imaging periods of 48 h.

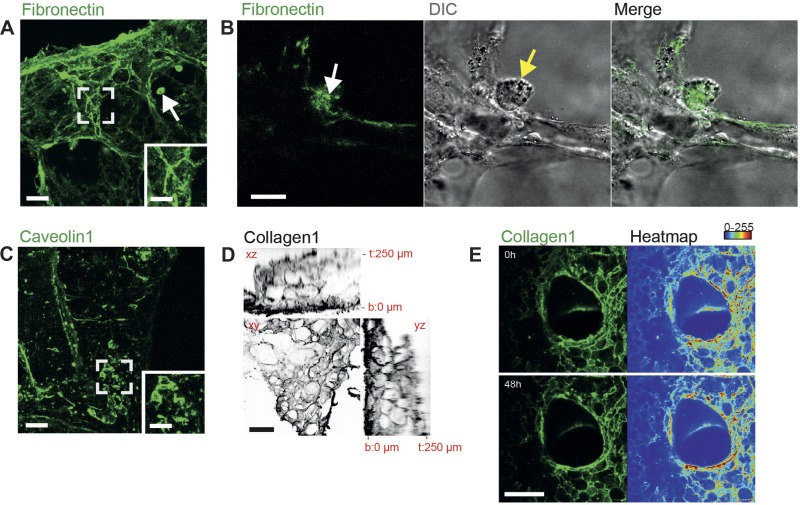

To illustrate the practical use of immunolabeling living tissue and the imaging thereof, we stained native 3D-LTCs with Abs against the ECM protein fibronectin and the cell-surface protein caveolin-1. In its insoluble and deposited form, fibronectin is fiber like, mostly related to fibroblasts, and displays a detrimental effect in fibrotic diseases (27). In fibroblasts, caveolin-1 is a major component of plasma membrane invaginations (caveolae) with migratory signaling functions and implications in regulating the ECM in pulmonary fibrosis (10, 32). Confocal 4D imaging of immunolabeled 3D-LTCs derived from healthy control mice identified fibronectin mostly as a distinct component of the ECM with fibrillar shapes and of various diameters (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, we found that big and mostly round cells, reminiscent of alveolar macrophages, positively stained for fibronectin (arrow in Fig. 2A). The 4D confocal microscopy in high optical resolution revealed that alveolar macrophages themselves incorporated immunolabeled fibronectin, which might be a direct consequence of the macrophages' phagocytic activity (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Movie S1; the online version of this article contains supplemental data). In contrast, caveolin-1-immunolabeled 3D-LTCs did show fibrillar staining of neither ECM components nor alveolar macrophages (Fig. 2C). Instead, spindle-shaped and flat cellular components of fibroblastic or endothelial origin were stained (Fig. 2C and magnified inset). The overall quality of the immunolabeling was independent of the position within the 3D-LTCs. We investigated this by immunostaining of collagen-1, which is one of the most abundant tissue macromolecule in the lung ECM. We found that all segments throughout the slices were thoroughly stained (Fig. 2D). Remarkably, the intensity of the staining remained very stable over time and was still clearly visible, even at 48 h after labeling (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Movie S2). The 4D confocal live-cell imaging allowed us to quantify the average fluorescence signal intensity of collagen-1-stained healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs during a period of 48 h, resulting in a 67 and 87% remnant fluorescence signal intensity in healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs, respectively, after 48 h of imaging (Fig. 3E). Part of the signal loss might be attributed to bleaching effects during the image acquisition, as a drop in fluorescence intensity was also found for the HOECHST signal (71 and 59% remnant fluorescence signal intensity after 48 h of imaging in healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs, respectively) (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 2.

Confocal four-dimensional (4D) time-lapse imaging of immunolabeled extracellular matrix (ECM) and single cells. A: immunolabeled fibronectin within a live 3D-LTCs. The inset shows a magnified view of the boxed area, indicating fibronectin's fibrillar structure. Scale bars, 100 and 50 μm, respectively. The confocal z-stack is shown as a maximum intensity projection (MIP). B: 4D confocal microscopy in high optical resolution presumably showing an alveolar macrophage (yellow arrow) that incorporated immunolabeled fibronectin (white arrow). Only one layer of a z-stack and one single frame of a time-lapse movie (Supplemental Movie S1) are shown. Scale bar, 20 μm. C: immunolabeled caveolin-1 within a live 3D-LTCs. The inset shows a magnified view of the boxed area displaying mostly flat fibroblast-like cells. Scale bars, 100 and 50 μm, respectively. The confocal z-stack is shown as a MIP. D: ortho-view of a living 3D-LTCs immunolabeled for collagen-1 (gray) showing homogeneous staining throughout a 250-μm section. b, Bottom of the 3D-LTC; t, top of the 3D-LTC. All views (xy, xz, yz) are depicted as MIP. Scale bar, 100 μm. E: two frames (0 h, 48 h) taken from a 48-h time lapse of a living 3D-LTC immunolabeled for collagen-1 (green), indicating stable immunostaining over time. The confocal z-stack is shown as a MIP. The right side of the panel shows a heatmap of the collagen-1 staining intensities. Blue and red indicate low and high signal intensities, respectively. Scale bar, 500 μm. (See also Supplemental Movie S2.) DIC, differential interference contrast.

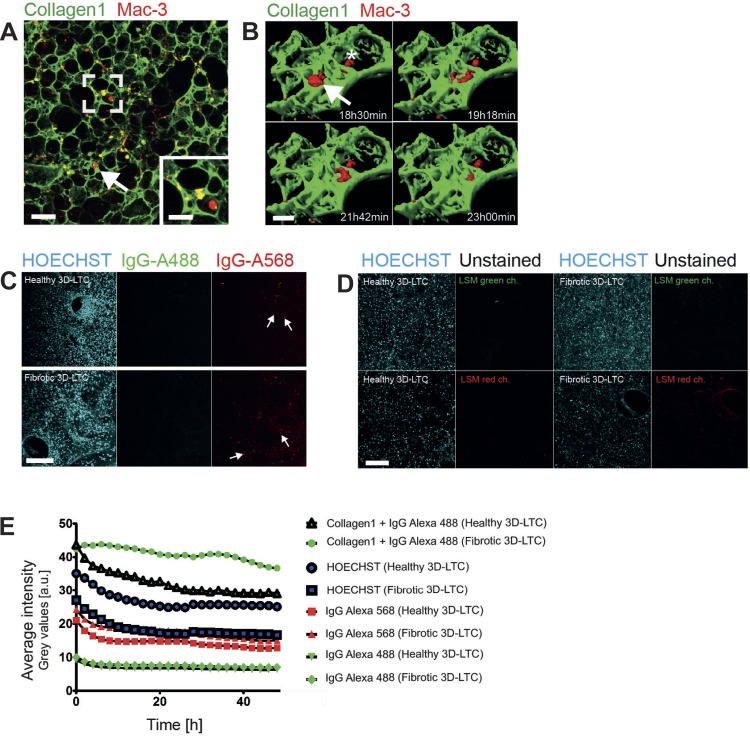

Fig. 3.

Living 3D-LTCs doubly immunolabeled for ECM and cells. A: double-immunolabeled vital 3D-LTC depicting collagen-1 in green and Mac-3 positive cells in red. Scale bars, 100 and 50 μm, respectively. The confocal z-stack is shown as a MIP. B: 3D surface rendered z-stack acquired from a time lapse of a double-immunolabeled live 3D-LTC depicting collagen-1 (green) and Mac-3 labeled cells (red). The arrow points to two highly migratory cells; the asterisk denotes one sessile cell (see also Supplemental Movie S4). Scale bar, 30 μm. C: this confocal panel displays living healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs that were stained for HOECHST (blue), as well as incubated for 2 h with the secondary antibodies anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor-488 (green) and anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor-568 (red). The white arrows point out cells positive for anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor-568 that assumingly phagocytized the secondary antibody. Scale bar, 200 μm. D: living healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs were stained for HOECHST (blue) and subsequently imaged with the same LSM settings as in C, demonstrating a higher background signal in the LSM red channel compared with the LSM green channel. Scale bar, 200 μm. E: time-wise quantification of the average fluorescence intensity of variously stained 3D-LTCs. The average fluorescence intensity of each time frame taken from a 48-h time lapse (1 z-stack/h) was analyzed. a.u., Arbitrary units.

Next, we double-immunolabeled mouse 3D-LTCs with Abs against collagen-1 and Mac-3, a glycoprotein expressed on the surface of tissue macrophages (16). Staining of collagen-1 was clearly connected to fibrillar ECM covering nearly all surfaces of the 3D-LTCs' ECM scaffold (Figs. 3A and Fig. 2E). The Mac-3 immunolabeled cells were reminiscent of alveolar macrophages. Surprisingly, we also found rounded cells, resembling tissue macrophages, which were exclusively stained for collagen-1, but not for Mac-3 (arrow in Fig. 3A), suggesting that previously described Mac-3 negative macrophage populations contribute to ECM remodeling in the lung (33). In contrast, we found Mac-3 and collagen-1 double-positive, as well as Mac-3 single-positive cells, advocating for numerous subpopulations of macrophages (see Fig. 3A and magnified inset). Clearly, Mac-3 labeled cells displayed diverse migratory activities. Interestingly, regions within the 3D-LTCs showing a higher migratory activity of Mac-3 labeled cells appeared to experience visible deformation effects within the ECM lung scaffold (Supplemental Movie S3). Figure 3B and Supplemental Movie S4 display a time lapse of a surface rendered z-stack acquired in high optical resolution, demonstrating two highly migratory active Mac-3 labeled cells (arrow) and a single sessile cell (asterisk). The specificity of the live immunostaining technique was demonstrated by fluorescently labeled IgG secondary Ab-only controls (Fig. 3C). Here, no structures other than round, alveolar macrophage-like cells (white arrows in Fig. 3C) were found positive for the fluorescently labeled IgG Abs. This advocates a high specificity of the immunolabeling in the 3D-LTCs, although indeed some fluorescent signals in macrophages may stem from the unspecific uptake of the Abs by phagocytosis.

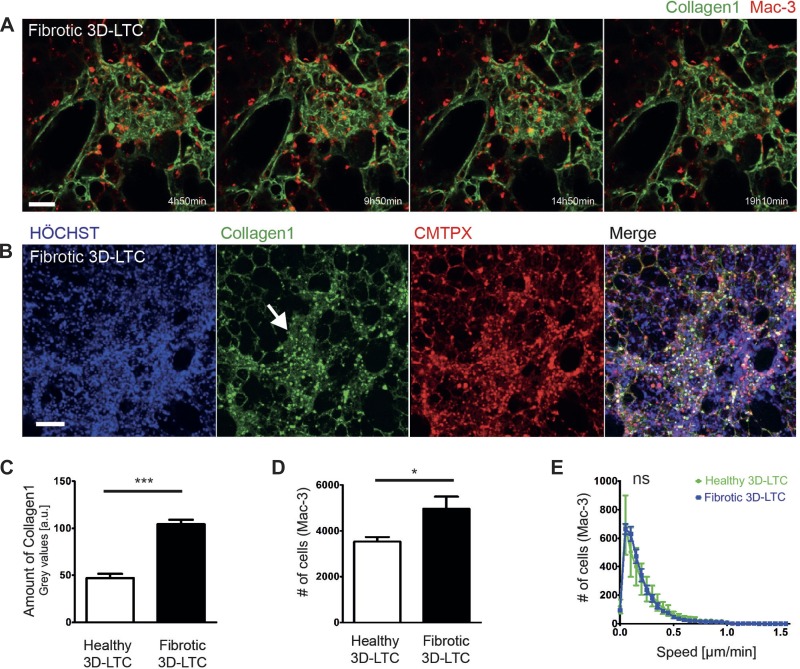

To demonstrate the suitability of our method for diseased tissue, we produced 3D-LTCs from bleomycin-treated mice (day 14). Bleomycin applied to the lung induces a strong transient fibrotic reaction and is commonly used to study pulmonary fibrosis in mice (26). We immunolabeled 3D-LTCs derived from fibrotic mouse lungs with Abs against collagen-1 and Mac-3 and applied long-term (>12 h) 4D confocal time-lapse imaging. Similar to the staining of healthy tissue (Fig. 2, D and E), even dense and ECM-rich fibrotic areas were found to be consistently stained for collagen-1 (Fig. 4A). Again, fluorescently labeled IgG secondary Ab-only controls remained mostly negative in fibrotic 3D-LTCs (Fig. 3, C–E). By quantifying the signal intensities of collagen-1 in the immunolabeled 3D-LTC, we found a significantly (P < 0.0001) higher amount of collagen-1 in fibrotic 3D-LTCs compared with healthy controls (Fig. 4C). Apparent fibrotic areas revealed a significantly increased accumulation of Mac-3-positive cells (P = 0.0195, Fig. 4D) of diverse migratory activities (Supplemental Movie S5). Surprisingly, when comparing the motility of Mac-3-positive cells in healthy vs. fibrotic 3D-LTCs by utilizing software-based automatic tracking, we could not detect any significant differences in the motility of these cells (Fig. 4E). This might speak for either a similar ratio of migratory subtypes of Mac-3-positive cells in healthy and fibrotic tissue, or for an artificial activation of Mac-3-positive cells in healthy tissue as a consequence of wounding due to the cutting procedure of the 3D-LTC. This, potentially, might level out the distribution of different migratory phenotypes. Additionally, we succeeded to perform triple IF stainings and 4D confocal time-lapse imaging of vital fibrotic 3D-LTCs by staining the cells' nuclei with the nontoxic HOECHST dye, the cell tracker dye CMTPX, and an Ab against collagen-1 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Immunolabeling of vital fibrotic mouse 3D-LTCs. A: double-immunolabeled live 3D-LTC depicting a collagen-1 stained densely packed fibrotic area in green and Mac-3-positive cells in red. Frames of different time points were taken from a 4D long-term time lapse as indicated. Scale bar, 50 μm. The confocal z-stack is shown as a MIP. B: triple immunofluorescence stainings and 4D confocal time-lapse imaging of vital fibrotic 3D-LTC stained for HOECHST in blue (nuclei), the cell tracker dye CMTPX in red (whole cells), and an antibody against collagen-1 in green. The white arrow indicates a collagen-1-dense fibrotic area. One single frame taken from a time-lapse movie is shown. The confocal z-stack is depicted as a MIP. Scale bar, 100 μm. C: quantitation and statistical evaluation of the amount of collagen-1 in vital healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs, showing a significantly (P < 0.0001) higher amount of collagen-1 in fibrotic 3D-LTCs. D: quantitation and statistical evaluation of the number of Mac-3-positive cells found in vital healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs, exhibiting a significant (P = 0.0195) increase in fibrotic areas. E: quantitation and statistical evaluation of the motility of Mac-3-positive cells found in vital healthy and fibrotic 3D-LTCs. No significant difference in the motility of Mac-3-positive cells could be detected. Values are means ± SD from various region of interests (ROIs) of 10 (C and D) and 5 (E) 3D-LTCs analyzed. ***P < 0.001. *P < 0.05. ns, Not significant.

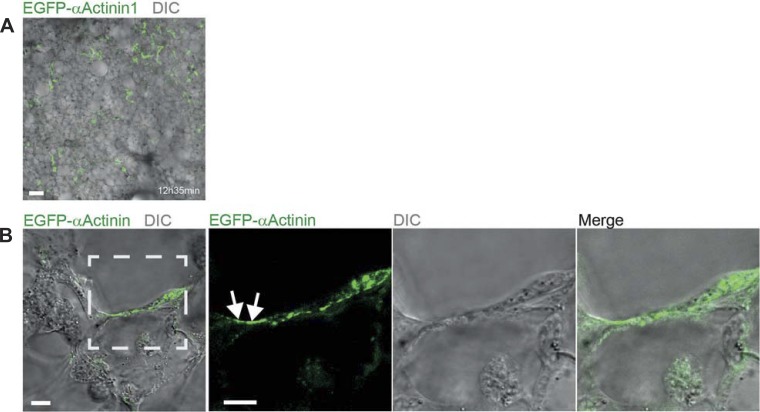

Next, we extended our immunolabeling technique of living tissue to study the dynamic behavior of intracellular proteins. For that, we reseeded normal 3D-LTCs with MLg lung fibroblasts, which were ectopically expressing the EGFP-tagged focal-adhesion and actin stress-fiber cross-linking protein α-actinin-1. Long-term 4D confocal time-lapse imaging surprisingly revealed that the EGFP-α-actinin-1 expressing fibroblasts incorporated into the 3D-LTCs tissue (Fig. 5A). However, although the incorporated fibroblasts were actively forming protrusions, they appeared to be mostly inactive in their migratory behavior (Supplemental Movie S6). Additionally, the incorporated fibroblasts displayed an increased membrane ruffling activity, which usually is an indicator of an inefficient adhesion of cellular protrusions like lamellipodia (2). As the externally added fibroblasts have to infiltrate dense cell layers in the 3D-LTC tissue, these cells may have difficulties to attach to the ECM of the 3D-LTC. Anyway, by applying 4D confocal time-lapse microscopy in high optical resolution, we could visualize the dynamics of subcellular structures like focal adhesion contacts (FAC) by means of adding transfected fibroblasts to native 3D-LTCs (Fig. 5B and Supplemental Movie S7). Similar observations were made by ectopically expressing two additional FAC markers, a truncated version of EGFP-P1f-8 and EGFP-VASP, in lung fibroblasts and by adding these cells to native 3D-LTCs (3, 17). Supplemental Movie S8 displays the dynamics of FACs, visualized by EGFP-P1f-8, in a fibroblast that incorporated into the tissue of a 3D-LTC (data of EGFP-VASP are not shown). FACs are multiprotein complexes forming functionally crucial interfaces between cells and their surrounding ECM. FACs were extensively studied in 2D cell culture systems, whereas their existence and functional nature within a 3D matrix and in vivo are still under heavy debate (9, 14, 21). Our technique, in combination with the immunolabeling of ECM components, might pave new roads in studying the dynamics of focal adhesions and their interaction with natural ECM.

Fig. 5.

Supplemented enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-α-actinin-1 expressing fibroblasts incorporate into native mouse 3D-LTCs and allow the visualization of subcellular structures. A: EGFP-α-actinin-1-expressing fibroblasts (green) incorporated into the 3D-LTCs (bright field). Scale bar, 100 μm. B: 4D confocal time-lapse microscopy in high-optical resolution of MLg mouse lung fibroblasts ectopically expressing the EGFP-tagged focal-adhesion and actin stress-fiber cross-linking protein α-actinin-1. The white arrow indicates a subcellular structure reminiscent of a focal adhesion usually found in two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems. The transfected cells were directly added to the 3D-LTCs and incorporated themselves into the native tissue. Only one layer of a z-stack and one single frame of a time-lapse movie (see Supplemental Movie S7) are shown. Scale bars, 10 μm.

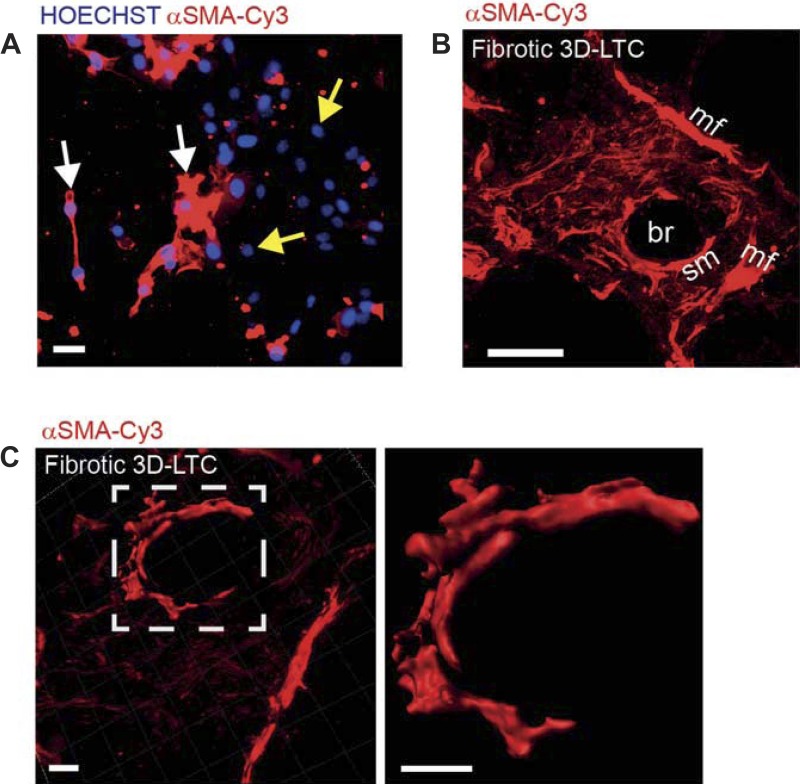

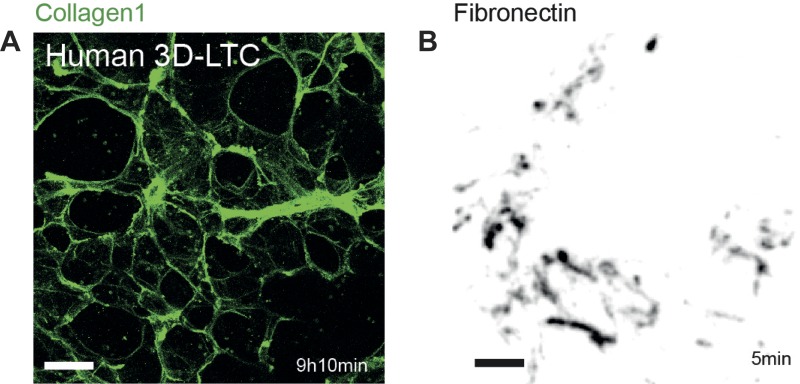

Comparable with transient liposomal transfection of plasmids in mammalian cells, recently commercially available reagents (Fuse-It, Ibidi) exist that allow the transfer of soluble molecules and diverse particles into living cells via liposomal membrane fusion. To apply immunolabeling of intracellular proteins, we initially validated the feasibility of this novel membrane fusion technology by transferring a Cy3 fluorophore-conjugated α-SMA Ab into MLg lung fibroblasts. Indeed, the transferred Ab was capable of staining α-SMA-positive stress fibers within living lung fibroblasts (Fig. 6A). Next, we transferred the α-SMA Ab into the native tissue cells of fibrotic 3D-LTCs by using the Fuse-It (Ibidi) technology. Strikingly, the α-SMA Ab was found to be successfully transferred into cells of the fibrotic 3D-LTCs, thus visualizing α-SMA-positive cells, which, according to their location and morphology, were highly reminiscent of smooth-muscle cells within a bronchiole and myofibroblasts in a highly fibrotic area (Fig. 6, B and C; Supplemental Movies S9 and S10). At the current stage, we cannot rule out any detrimental or inhibitory effects of the loading of the cells with the α-SMA Ab, as, depending on the efficiency of the transfer into the cells, most cells are supposed to uptake the Ab. This also might include cells that usually do not express α-SMA, such as epithelial cells. Further detailed studies are needed to investigate the effect of the protein or Ab uptake on the behavior of cells in vitro or in 3D-LTCs. Prospectively, the staining of living myofibroblasts in their native microenvironment of 3D-LTCs and by the 4D confocal imaging thereof will provide novel ways of studying the development and progression of fibrotic diseases. Finally, in addition to immunolabeling and 4D imaging of vital mouse tissue, we also show here that our methodology is successfully applicable to human tissue (Fig. 7A and Supplemental Movie S11), as well as to the study of the dynamic interaction between cells and their ECM in conventional 2D cell culture systems (Fig. 7B and Supplemental Movie S12).

Fig. 6.

Immunolabeling of cytoskeletal α-smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive stress fibers in living native tissue cells of fibrotic 3D-LTCs. A: a Cy-3 fluorophore-conjugated α-SMA antibody was transferred into MLg lung fibroblasts by membrane-fusion technology (Fuse-It, Ibidi). Fibroblasts with α-SMA-positive stress fibers were stained in red (white arrows). Fibroblasts that did not express α-SMA remained unstained aside from HOECHST staining in blue (yellow arrows). Only one single frame taken from a time-lapse movie is shown. Scale bar, 20 μm. B: a Cy-3 fluorophore-conjugated α-SMA antibody was transferred into the cells by means of a membrane fusion technology (Fuse-It, Ibidi). By binding, the antibody indicates α-SMA-positive stress fibers within smooth-muscle cells and myofibroblasts in fibrotic foci. br, Bronchiole; mf, myofibroblasts; sm, smooth-muscle cell. The confocal z-stack is shown as a MIP. Scale bar, 50 μm. C: a Cy-3 fluorophore-conjugated α-SMA antibody was transferred into the native tissue cells of fibrotic 3D-LTCs by membrane-fusion technology (Fuse-It). The picture on the right side of the panel displays a 3D surface rendered z-stack of α-SMA-positive smooth-muscle cells overlaid to a larger 3D volume rendered z-stack of a fibrotic area. The picture on the left side of the panel is a magnified view of the 3D surface-rendered z-stack of α-SMA-positive smooth-muscle cells within the fibrotic area. Only one single frame taken from a time-lapse movie (see Supplemental Movie S10) is shown. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Fig. 7.

Immunolabeling of human derived 3D-LTCs and of cells cultured in a 2D cell culture system. A: 3D-LTC derived from human lung tissue and immunolabeled with a collagen-1 antibody. The confocal z-stack is shown as a MIP. Scale bar, 200 μm. B: live MLg fibroblasts were cultured on the glass surface of a conventional 2D cell culture imaging dish and immunolabeled with a fibronectin antibody. Deposited and extracellular fibronectin is shown in gray. For better visualization, the image was contrast inverted. The image was taken from a time-lapse movie. Scale bar, 20 μm.

In conclusion, our application of multidimensional immunolabeling of living ex vivo tissue and real-time 4D multichannel imaging thereof provides a novel methodology for studying the dynamic interaction of cells and their surrounding ECM. In the laboratory routine, IF staining methods play an integral part in labeling fixed tissues and cells, but indirect IF has also been successfully applied in situ for real-time fluorescence imaging in intravital microscopy (18, 22, 23). Here, we combined the power of 3D-LTCs and indirect IF techniques to pave the way for investigating the dynamic interaction of living tissue and cells in low- and high-optical resolution. The advantages of our reported methodology are manifold. First, it results in multidimensional labeling of living ex vivo tissue derived from healthy or diseased organs by exploiting all of the flexibility of indirect IF stainings. Second, it allows the in depth investigation of the dynamics of subcellular structures, such as FACs, by utilizing high-resolution and magnification lenses. Third, by immunolabeling intracellular structures, such as α-SMA-positive stress fibers, the transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts following transforming growth factor-β treatment might be investigated in living tissue by long-term time-lapse 4D confocal microscopy. While our study provides a proof of principle for using Abs and IF on living cells and cultured ex vivo tissue, we cannot rule out possible inhibitory or adverse functional effects due to binding of the Abs to their target antigens, either in the ECM, on the cells' surface, or also in case of the FuseIt (Ibidi) approach to intracellular structures. To date, we did not detect detrimental effects of immunolabeled ECM on the migration capacity of Mac-3-labeled cells. It is tempting to speculate that the migration capacity of activated (myo)fibroblasts is compromised by masking certain epitopes in the ECM via live immunolabeling. Intriguingly, this could be therapeutically exploited in interstitial lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In that respect, it is possible that the fluorescent immunolabeling of living tissue, as exemplified here, could be further extended to intravital microscopy by using ECM Ab markers, finally studying in vivo the dynamic interaction of cells with the ECM. In summary, we trust that this novel and original application of high-resolution 4D imaging will provide unprecedented insight into pathological processes of cell-matrix interaction during homeostasis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Helmholtz Association, the German Center for Lung Research (DZL) and European Research Council Starting Grant ERC-2010-StG 261302.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: G.B. and O.E. conception and design of research; G.B., S.V., and M.L. performed experiments; G.B., S.V., M.K., and O.E. analyzed data; G.B., M.K., and O.E. interpreted results of experiments; G.B. prepared figures; G.B. drafted manuscript; G.B., S.V., M.K., and O.E. edited and revised manuscript; G.B., S.V., M.L., M.K., and O.E. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Kyra Peters and Nadine Adam for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Booth AJ, Hadley R, Cornett AM, Dreffs AA, Matthes SA, Tsui JL, Weiss K, Horowitz JC, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Moore BB, Martinez FJ, Niklason LE, White ES. Acellular normal and fibrotic human lung matrices as a culture system for in vitro investigation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 866–876, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borm B, Requardt RP, Herzog V, Kirfel G. Membrane ruffles in cell migration: indicators of inefficient lamellipodia adhesion and compartments of actin filament reorganization. Exp Cell Res 302: 83–95, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgstaller G, Gregor M, Winter L, Wiche G. Keeping the vimentin network under control: cell-matrix adhesion-associated plectin 1f affects cell shape and polarity of fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell 21: 3362–3375, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgstaller G, Oehrle B, Koch I, Lindner M, Eickelberg O. Multiplex profiling of cellular invasion in 3D cell culture models. PloS One 8: e63121, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science 294: 1708–1712, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Cell interactions with three-dimensional matrices. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14: 633–639, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dandurand RJ, Wang CG, Phillips NC, Eidelman DH. Responsiveness of individual airways to methacholine in adult rat lung explants. J Appl Physiol 75: 364–372, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher RL, Vickers AE. Preparation and culture of precision-cut organ slices from human and animal. Xenobiotica 43: 8–14, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraley SI, Feng Y, Krishnamurthy R, Kim DH, Celedon A, Longmore GD, Wirtz D. A distinctive role for focal adhesion proteins in three-dimensional cell motility. Nat Cell Biol 12: 598–604, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz JG, Minguet S, Navarro-Lerida I, Lazcano JJ, Samaniego R, Calvo E, Tello M, Osteso-Ibanez T, Pellinen T, Echarri A, Cerezo A, Klein-Szanto AJ, Garcia R, Keely PJ, Sanchez-Mateos P, Cukierman E, Del Pozo MA. Biomechanical remodeling of the microenvironment by stromal caveolin-1 favors tumor invasion and metastasis. Cell 146: 148–163, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 211–224, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinnell F. Fibroblast biology in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Trends Cell Biol 13: 264–269, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakkinen KM, Harunaga JS, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Direct comparisons of the morphology, migration, cell adhesions, and actin cytoskeleton of fibroblasts in four different three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Tissue Eng Part A 17: 713–724, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harunaga JS, Yamada KM. Cell-matrix adhesions in 3D. Matrix Biol 30: 363–368, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashemi E, Dobrota M, Till C, Ioannides C. Structural and functional integrity of precision-cut liver slices in xenobiotic metabolism: a comparison of the dynamic organ and multiwell plate culture procedures. Xenobiotica 29: 11–25, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho MK, Springer TA. Tissue distribution, structural characterization, and biosynthesis of Mac-3, a macrophage surface glycoprotein exhibiting molecular weight heterogeneity. J Biol Chem 258: 636–642, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt MR, Critchley DR, Brindle NP. The focal adhesion phosphoprotein, VASP. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 30: 307–311, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Pressure-induced leukocyte margination in lung postcapillary venules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L407–L412, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson S, Rabinovitch P. Ex vivo imaging of excised tissue using vital dyes and confocal microscopy. Curr Protoc Cytom 9, unit 9: 39, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinman HK, Martin GR. Matrigel: basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin Cancer Biol 15: 378–386, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubow KE, Horwitz AR. Reducing background fluorescence reveals adhesions in 3D matrices. Nat Cell Biol 13: 3–5; author reply 5–7, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuebler WM, Parthasarathi K, Lindert J, Bhattacharya J. Real-time lung microscopy. J Appl Physiol 102: 1255–1264, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuebler WM, Parthasarathi K, Wang PM, Bhattacharya J. A novel signaling mechanism between gas and blood compartments of the lung. J Clin Invest 105: 905–913, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberati TA, Randle MR, Toth LA. In vitro lung slices: a powerful approach for assessment of lung pathophysiology. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 10: 501–508, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann BK, Gobin AS, Tsai AT, Schmedlen RH, West JL. Smooth muscle cell growth in photopolymerized hydrogels with cell adhesive and proteolytically degradable domains: synthetic ECM analogs for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 22: 3045–3051, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouratis MA, Aidinis V. Modeling pulmonary fibrosis with bleomycin. Curr Opin Pulm Med 17: 355–361, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pankov R, Yamada KM. Fibronectin at a glance. J Cell Sci 115: 3861–3863, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parrish AR, Gandolfi AJ, Brendel K. Precision-cut tissue slices: applications in pharmacology and toxicology. Life Sci 57: 1887–1901, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raeber GP, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels: a novel model system for proteolytically mediated cell migration. Biophys J 89: 1374–1388, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uhl FE, Vierkotten S, Wagner DE, Burgstaller G, Costa R, Koch I, Lindner M, Meiners S, Eickelberg O, Konigshoff M. Preclinical validation and imaging of Wnt-induced repair in human 3D lung tissue cultures. Eur Respir J. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Midwoud PM, Merema MT, Verpoorte E, Groothuis GM. A microfluidic approach for in vitro assessment of interorgan interactions in drug metabolism using intestinal and liver slices. Lab Chip 10: 2778–2786, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang XM, Zhang Y, Kim HP, Zhou Z, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Liu F, Ifedigbo E, Xu X, Oury TD, Kaminski N, Choi AM. Caveolin-1: a critical regulator of lung fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med 203: 2895–2906, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westphalen K, Gusarova GA, Islam MN, Subramanian M, Cohen TS, Prince AS, Bhattacharya J. Sessile alveolar macrophages communicate with alveolar epithelium to modulate immunity. Nature 506: 503–506, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf K, Friedl P. Extracellular matrix determinants of proteolytic and non-proteolytic cell migration. Trends Cell Biol 21: 736–744, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang S. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nat Biotechnol 21: 1171–1178, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.