Abstract

Objective

Encouraging help-seeking for mental illness is essential for prevention of suicide. This study examined the relationship between individual characteristics, neighbourhood contexts and help-seeking intentions for mental illness for the purpose of elucidating the role of neighbourhood in the help-seeking process.

Design, setting and participants

A cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted among Japanese adults aged 20–59 years in June 2014. Eligible respondents who did not have a serious health condition were included in this study (n=3308).

Main outcome measures

Participants were asked how likely they would be to seek help from someone close to them (informal help) and medical professionals (formal help), respectively, if they were suffering from serious mental illness. Path analysis with structural equation modelling was performed to represent plausible connections between individual characteristics, neighbourhood contexts, and informal and formal help-seeking intentions.

Results

The acceptable fitting model indicated that those who had a tendency to consult about everyday affairs were significantly more likely to express an informal help-seeking intention that was directly associated with a formal help-seeking intention. Those living in a communicative neighbourhood, where neighbours say hello whenever they pass each other, were significantly more likely to express informal and formal help-seeking intentions. Those living in a supportive neighbourhood, where neighbours work together to solve neighbourhood problems, were significantly more likely to express an informal help-seeking intention. Adequate health literacy was directly associated with informal and formal help-seeking intentions, along with having an indirect effect on the formal help-seeking intention through developed positive perception of professional help.

Conclusions

The results of this study bear out the hypothesis that neighbourhood context contributes to help-seeking intentions for mental illness. Living in a neighbourhood with a communicative atmosphere and having adequate health literacy were acknowledged as possible facilitating factors for informal and formal help-seeking for mental illness.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, MENTAL HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Previous studies have revealed the individual factors that may inhibit or facilitate help-seeking for mental illness, but less is known about neighbourhood factors. This study represents the first attempt to elucidate multifactorial mechanisms for help-seeking using structural equation modelling.

Our final structural equation model illustrated the pathways linking individual and neighbourhood factors to informal and formal help-seeking intentions, and bore out the hypothesis that neighbourhood context contributes to help-seeking intentions for mental illness.

The study design is cross-sectional and self-reported, so we cannot reject the possibility of reverse causation or common method bias. The study participants seem not to be representative of the general population. Further studies are needed to confirm the findings and refine the model. Moreover, the relationship between help-seeking intentions and actual help-seeking should be investigated in future.

Introduction

The WHO published its first report on suicide prevention in 2014.1 According to the report, more than 800 000 people die by suicide every year. While the reasons that people commit suicide vary widely, almost all suicide victims have signs or symptoms of mental illness at the time of their death. Unfortunately, people do not always seek help when they suffer mental illness or have suicidal thoughts.2 3 Encouraging help-seeking for mental illness is essential for prevention of suicide.

A socioecological perspective acknowledges that health behaviour is influenced by the social environment.4 While the proximal cause of health behaviour lies within the individual rather than in the social environment, changes in the social environment will produce changes in individuals. Similarly to other health behaviours, help-seeking for mental illness is considered to be determined through the interaction between individuals and their environment.2 3 5 Traditionally, public health strategies for encouraging help-seeking have focused on modifying individual factors such as knowledge and skills. Once the factors in the social environment that can affect help-seeking are identified, the focus of strategy will broaden to include the environmental factors.

The social environment is a broad multidimensional concept that includes the groups to which we belong, the neighbourhoods in which we live and the policies we create to order our lives.6 Neighbourhood is the next smallest social unit after family, in which face-to-face interactions occur among members. Previous studies have revealed that neighbourhood context, or more specifically neighbourhood social capital, is associated with health behaviours such as smoking, drinking, diet and physical activity.7 The impact of neighbourhood context on health behaviour may be worth considering when developing public health strategies for encouraging help-seeking. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies examining to what extent neighbourhood context contributes to help-seeking and what factors are responsible for the neighbourhood effect. Little is known about the role of the neighbourhood in the help-seeking process.

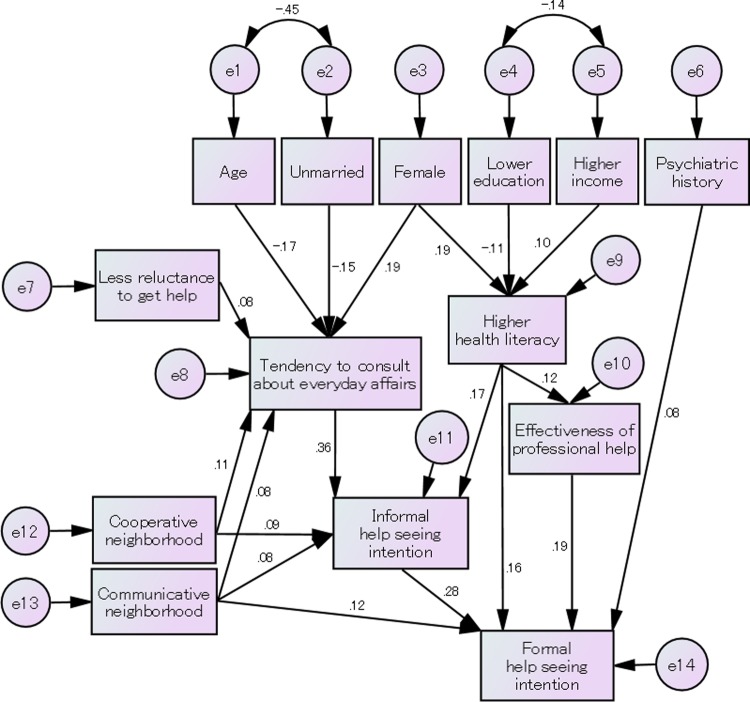

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between individual characteristics, neighbourhood contexts and help-seeking intentions for mental illness. On the basis of a review of the literature, we created a hypothesis model linking individual and neighbourhood factors, to informal and formal help-seeking intentions, to represent plausible multifactorial mechanisms for help-seeking (figure 1). Compared to previous studies, this study examined a wider variety of factors that may affect help-seeking decision-making. Path analysis with structural equation modelling was performed to test the hypothesis model and to elucidate the role of neighbourhood in the help-seeking process. We believe the findings of this study will provide a new direction for public health strategies for encouraging help-seeking or suicide prevention policies.

Figure 1.

Relationship between individual and neighbourhood factors and help-seeking intentions for mental illness (hypothesis model).

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted in June 2014 among Japanese adults aged 20–59 years who lived in four prefectures, Chiba, Niigata, Nagano and Fukuoka, in Japan. Medical professionals and students were excluded from recruitment because their attitudes to help-seeking are seen as different from those of the larger population.

An online research company (INTAGE, Inc, Tokyo, Japan) was contracted to create web questionnaire forms and to collect anonymous responses (n=3200). The company has a nationwide research panel of 1.2 million registrants. At the time of the survey, those registrants aged 20–59 years who lived in the four prefectures and were not medical professionals or students, totalled 46 258 (20 071 males and 26 187 females). Recruitment emails were sent to 8721 eligible registrants who were randomly selected from each age/gender/prefecture stratum. Applicants for participation in the survey were accepted in the order of receipt until the number of participants reached the quotas (100 people for each age/gender/prefecture stratum). All participants voluntarily agreed to complete the survey. A total of 3365 responses were obtained over 8 days of recruitment. Of these, 6 participants reported having serious health conditions and 51 participants provided incomplete or inconsistent answers to questions. The remaining 3308 participants were finally included in the study.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants. According to the 2010 national census,8 the percentage of the Japanese population aged 20–59 years with university degrees was 21.9%, considerably lower than that of this study (40.4%), whereas the percentages of married and employed population were 58.2% and 72.7%, respectively, almost equal to those of this study (59.3% and 76.7%, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| N | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1621 | 49.0 |

| Female | 1687 | 51.0 |

| Age, years | ||

| 20–29 | 797 | 24.1 |

| 30–39 | 842 | 25.5 |

| 40–49 | 837 | 25.3 |

| 50–59 | 832 | 25.2 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 1066 | 32.2 |

| Junior college/vocational school | 905 | 27.4 |

| University/graduate school | 1337 | 40.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1960 | 59.3 |

| Unmarried | 1184 | 35.8 |

| Divorced/widowed | 164 | 5.0 |

| Household | ||

| One person | 464 | 14.0 |

| More than two people | 2844 | 86.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| No occupation | 770 | 23.3 |

| Temporary or part-time job | 560 | 16.9 |

| Full-time job | 1978 | 59.8 |

| Household income | ||

| <2.0 million yen* | 363 | 11.0 |

| 2.0–3.9 million | 777 | 23.5 |

| 4.0–5.9 million | 937 | 28.3 |

| 6.0–7.9 million | 618 | 18.7 |

| 8.0–9.9 million | 347 | 10.5 |

| 10.0+ million | 266 | 8.0 |

| Medical condition | ||

| No disease | 2449 | 73.6 |

| Any disease | 879 | 26.4 |

*One million yen was about US$10 000 at the time of the survey.

Measures

The questionnaire asked about help-seeking intentions for mental illness, medical condition, exposure to mental illness, health literacy, belief about professional help, social network, attitudes to everyday affairs and neighbourhood context. The components of the questionnaire relevant to this study are detailed below.

Help-seeking intentions for mental illness

In the absence of a gold standard, the most commonly used methodology was used for measuring help-seeking intentions in this study.9 Participants were asked to rate how likely they would be to seek help from: (1) someone close to them, such as family, relatives, friends and colleagues (informal sources) and (2) medical professionals (formal sources), respectively, if they were suffering serious mental illness. Those who gave affirmative responses on a four-point scale (certainly yes/probably yes/probably not/certainly not) were counted as having informal and formal help-seeking intentions, respectively. Those who gave negative responses to both questions were counted as having no help-seeking intentions.

Medical condition

Participants were asked to report whether they had any chronic disease undergoing medical treatment. The list included hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, stroke, heart trouble, renal failure, cancer, insomnia, depression and others.

Exposure to mental illness

Participants were asked about their psychiatric history—whether they had ever consulted health professionals about their mental health. The Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS)10 was used to determine the extent of participants’ contact with people who were mentally ill. The first subscale consists of four questions: living with, working with, living near and having a close friendship with people with mental illness, either at present or in the past. Those who answered ‘yes’ to at least one question were counted as having had contact with people with mental illness. Participants were also asked whether someone close to them was engaged in psychiatry.

Health literacy

The 14-item Health Literacy Scale (HLS-14)11 was used to measure health literacy. The scale consists of five items for functional literacy, five items for communicative literacy and four items for critical literacy. Respondents choose one of five options in response to each statement. The scores on the items were summed up to give the HLS-14 score (range 14–70 points) for each respondent. Higher scores indicate having better health literacy.

Belief about professional help

Referring to the questionnaires for the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders,12 perceived effectiveness of professional help was measured using the following two questions: (1) of the people who see a professional for serious mental illness, what per cent do you think are helped? (range 0–100%); (2) of those with serious mental illness who do not get professional help, what per cent do you think get better even without it? (range 0–100%). The percentages on the two questions were subtracted (question 1 minus question 2) and then the answers were trichotomised into positive (1<%, better than no help), neutral (0%, equal to no help) and negative (<−1%, worse than no help). Participants were also asked whether they would be embarrassed if their friends knew they were getting professional help for mental illness.

Social network

The abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6)13 14 was used to measure social network. The scale consists of three items for family ties and three items for friendship ties. Respondents choose one of six options in response to each statement. The scores on the items were summed up to give the LSNS-6 score (range 6–36 points) for each respondent. Higher scores indicate having greater ties to family and friends.

Attitudes to everyday affairs

Participants were asked to rate how likely they would be to talk with someone close to them about a problem that brought stress and distress into their everyday lives. The question was derived from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions (one of the statistical surveys by the Japanese Government). Those who gave affirmative responses on a four-point scale (certainly yes/probably yes/probably not/certainly not) were considered as having a tendency to consult about everyday affairs. Participants were also asked whether they felt reluctant to get help from others.

Neighbourhood context

A variety of measures of neighbourhood context have been proposed, but none of them is recommended as a gold standard. Neighbourhood is characterised as a geographically localised community often with face-to-face interactions among members. Referring to the questionnaire for the Health Survey of People Affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake,15 four specific features of neighbourhood context relevant to neighbourhood social capital were assessed using the following statements, respectively: (1) neighbours say hello whenever they pass each other (communicativeness); (2) neighbours trust in each other (trustfulness); (3) neighbours help each other (helpfulness); and (4) neighbours work together to solve neighbourhood problems (cooperativeness). Respondents choose one of five options (strongly agree/agree/not sure/disagree/strongly disagree) in response to each statement. The internal consistency was adequate (Cronbach α=0.87). For analysis, the responses were dichotomised into positive (strongly agree/agree) and negative (not sure/disagree/strongly disagree).

Statistical analysis

The percentages of participants who expressed help-seeking intentions were compared using χ2 test. Significant variables on the univariate analysis were incorporated into a multiple logistic regression model to identify individual and neighbourhood factors independently associated with help-seeking intentions. Adjusted ORs and 95% CIs were calculated from the models.

Path analysis with structural equation modelling was performed to test the hypothesis model linking individual and neighbourhood factors to help-seeking intentions for mental illness (figure 1). In case of serious mental illness, formal (professional) help must be the best way to solve the problem. A formal help-seeking intention was therefore placed in the structural equation model as the outcome variable. On the basis of previous studies,5 16–18 an informal help-seeking intention was assumed to bring the formal help-seeking intention. Besides sociodemographics, significant predictors derived from the multiple logistic regression analysis were placed in position according to the most plausible hypothesis. The strength of the relationship between two variables was estimated as a standardised regression weight (ie, path coefficient, β). While there are no established guidelines regarding sample size requirements for structural equation modelling, a generally accepted rule of thumb is that the minimum sample size should ideally be 20 times the number of variables in the model.19 The model generated in this study consisted of 14 variables and thus the final sample of 3308 was sufficient for path analysis. Model fitness was assessed by goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). For GFI and AGFI, a value of >0.9 indicates a good fit, and for RMSEA, a value of <0.08 is considered to be acceptable.20 The initial model was improved by trimming paths with non-significant contributions. The final model consisted of paths with a path coefficient of >0.05 or <−0.05 (p<0.05).

All statistical analyses except for the path analysis were performed using SAS V.9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The path analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Amos V.22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA). Significant levels were set at p<0.05.

Results

Table 2 shows the percentages of participants who expressed the help-seeking intentions for mental illness. Of the 3308 participants, 67.7% (n=2241) and 75.6% (n=2500) reported that they would seek help from informal and formal sources, respectively, in case of serious mental illness. The majority (n=1938, 58.6%) expressed both informal and formal help-seeking intentions. All the individual (A, B, C, D) and neighbourhood (E) factors showed significant associations with either or both informal and formal help-seeking intentions in univariate analyses. Contrary to theoretical expectations, help-seeking intentions were more frequently observed in those who reported embarrassment towards professional help. This factor was considered irrelevant and removed from further analysis.

Table 2.

Percentages of participants who expressed help-seeking intentions for mental illness

| N | Informal sources |

Formal sources |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Sociodemographics | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 1621 | 967 | 59.7% | <0.001 | 1170 | 72.2% | <0.001 |

| Female | 1687 | 1274 | 75.5% | 1330 | 78.8% | ||

| Age, years | |||||||

| 20–29 | 797 | 530 | 66.5% | 0.483 | 551 | 69.1% | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 842 | 584 | 69.4% | 638 | 75.8% | ||

| 40–49 | 837 | 574 | 68.6% | 647 | 77.3% | ||

| 50–59 | 832 | 553 | 66.5% | 664 | 79.8% | ||

| Education | |||||||

| High school | 1066 | 682 | 64.0% | <0.001 | 765 | 71.8% | 0.002 |

| Junior college/vocational school | 905 | 651 | 71.9% | 706 | 78.0% | ||

| University/graduate school | 1337 | 908 | 67.9% | 1029 | 77.0% | ||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 1960 | 1448 | 73.9% | <0.001 | 1543 | 78.7% | <0.001 |

| Unmarried | 1184 | 696 | 58.8% | 829 | 70.0% | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 164 | 97 | 59.1% | 128 | 78.0% | ||

| Household | |||||||

| One person | 464 | 251 | 54.1% | <0.001 | 326 | 70.3% | 0.004 |

| More than two people | 2844 | 1990 | 70.0% | 2174 | 76.4% | ||

| Occupation | |||||||

| No occupation | 770 | 576 | 74.8% | <0.001 | 594 | 77.1% | 0.506 |

| Temporary or part-time job | 560 | 389 | 69.5% | 422 | 75.4% | ||

| Full-time job | 1978 | 1276 | 64.5% | 1484 | 75.0% | ||

| Household income | |||||||

| <2.0 million yen* | 363 | 207 | 57.0% | <0.001 | 243 | 66.9% | <0.001 |

| 2.0–3.9 million | 777 | 498 | 64.1% | 569 | 73.2% | ||

| 4.0–5.9 million | 937 | 643 | 68.6% | 697 | 74.4% | ||

| 6.0–7.9 million | 618 | 436 | 70.6% | 490 | 79.3% | ||

| 8.0–9.9 million | 347 | 259 | 74.6% | 280 | 80.7% | ||

| 10.0+ million | 266 | 198 | 74.4% | 221 | 83.1% | ||

| B. Medical condition and exposure to mental illness | |||||||

| Medical condition | |||||||

| No disease | 2449 | 1666 | 68.0% | 0.829 | 1786 | 72.9% | <0.001 |

| Any disease | 879 | 400 | 45.5% | 714 | 81.2% | ||

| Psychiatric history | |||||||

| No | 2689 | 1821 | 67.7% | 0.949 | 1983 | 73.7% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 619 | 420 | 67.9% | 517 | 83.5% | ||

| Contact with people with mental illness | |||||||

| No | 2006 | 1260 | 62.8% | <0.001 | 1421 | 70.8% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1302 | 981 | 75.3% | 1079 | 82.9% | ||

| Familiar people engaged in psychiatry | |||||||

| No | 3157 | 2125 | 67.3% | 0.015 | 2382 | 75.5% | 0.452 |

| Yes | 151 | 116 | 76.8% | 118 | 78.1% | ||

| C. Health literacy and belief about professional help | |||||||

| Health literacy (HLS-14) | |||||||

| Low | 1853 | 1097 | 59.2% | <0.001 | 1243 | 67.1% | <0.001 |

| High | 1455 | 1144 | 78.6% | 1257 | 86.4% | ||

| Embarrassment toward professional help | |||||||

| No | 1644 | 1033 | 62.8% | <0.001 | 1133 | 68.9% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1664 | 1208 | 72.6% | 1367 | 82.2% | ||

| Perceived effectiveness of professional help | |||||||

| Negative | 287 | 165 | 57.5% | <0.001 | 160 | 55.7% | <0.001 |

| Neutral | 869 | 495 | 57.0% | 533 | 61.3% | ||

| Positive | 2152 | 1581 | 73.5% | 1807 | 84.0% | ||

| D. Social network and attitudes to everyday affairs | |||||||

| Social network (LSNS-6) | |||||||

| Low | 1891 | 1120 | 59.2% | <0.001 | 1360 | 71.9% | <0.001 |

| High | 1417 | 1121 | 79.1% | 1140 | 80.5% | ||

| Tendency to consult about everyday affairs | |||||||

| No | 1675 | 817 | 48.8% | <0.001 | 1152 | 68.8% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1633 | 1424 | 87.2% | 1348 | 82.5% | ||

| Reluctance to get help | |||||||

| No | 1713 | 1220 | 71.2% | <0.001 | 1273 | 74.3% | 0.080 |

| Yes | 1595 | 1021 | 64.0% | 1227 | 76.9% | ||

| E. Neighbourhood context | |||||||

| Communicative neighbourhood | |||||||

| No | 1221 | 675 | 55.3% | <0.001 | 770 | 63.1% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2087 | 1566 | 75.0% | 1730 | 82.9% | ||

| Trustful neighbourhood | |||||||

| No | 2550 | 1651 | 64.7% | <0.001 | 1870 | 73.3% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 758 | 590 | 77.8% | 630 | 83.1% | ||

| Helpful neighbourhood | |||||||

| No | 2311 | 1448 | 62.7% | <0.001 | 1657 | 71.7% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 997 | 793 | 79.5% | 843 | 84.6% | ||

| Cooperative neighbourhood | |||||||

| No | 2045 | 1227 | 60.0% | <0.001 | 1434 | 70.1% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1263 | 1014 | 80.3% | 1066 | 84.4% | ||

*One million yen was about US$10 000 at the time of the survey.

Table 3 shows the results of multiple logistic regression analysis. The following three individual and one neighbourhood factor were significantly associated with informal and formal help-seeking intentions: contact with people with mental illness, health literacy, perceived effectiveness of professional help, tendency to consult about everyday affairs and communicative neighbourhood. Besides these, marital status, social network and cooperative neighbourhood, were significantly associated with an informal help-seeking intention, while medical condition and psychiatric history were significantly associated with a formal help-seeking intention. The highest ORs for informal and formal help-seeking intentions were found in tendency to consult about everyday affairs (OR 5.21) and perceived effectiveness of professional help (OR 2.16), respectively.

Table 3.

Logistic regression predicting help-seeking intentions for mental illness

| Informal sources |

Formal sources |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

|||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.18 | 0.98 | 1.43 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 1.20 |

| Age | ||||||

| Plus 10 years | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.19 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school | 0.92 | 0.76 | 1.11 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.04 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 0.77* | 0.61 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 1.13 |

| Divorced/widowed | 0.60* | 0.40 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.57 | 1.41 |

| Household | ||||||

| One person | 1.05 | 0.80 | 1.38 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 1.05 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| No occupation | 1.14 | 0.90 | 1.44 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.07 |

| Household income | ||||||

| Plus 2 million yen | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.13 |

| Medical condition | ||||||

| Any disease | 0.94 | 0.77 | 1.16 | 1.52*** | 1.20 | 1.92 |

| Psychiatric history | ||||||

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.79 | 1.26 | 1.66*** | 1.27 | 2.17 |

| Contact with people with mental illness | ||||||

| Yes | 1.39*** | 1.15 | 1.68 | 1.27* | 1.05 | 1.55 |

| Familiar people engaged in psychiatry | ||||||

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.66 | 1.61 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 1.24 |

| Health literacy (HLS-14) | ||||||

| Plus 1 point | 1.06*** | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.07*** | 1.06 | 1.09 |

| Perceived effectiveness of professional help | ||||||

| Positive | 1.43*** | 1.26 | 1.62 | 2.16*** | 1.90 | 2.45 |

| Social network (LSNS-6) | ||||||

| Plus 1 point | 1.04*** | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.03 |

| Tendency to consult about everyday affairs | ||||||

| Yes | 5.21*** | 4.31 | 6.30 | 1.66*** | 1.37 | 2.02 |

| Reluctance to get help | ||||||

| No | 1.26** | 1.06 | 1.50 | 0.78** | 0.65 | 0.93 |

| Communicative neighbourhood | ||||||

| Yes | 1.30* | 1.06 | 1.58 | 1.78*** | 1.45 | 2.18 |

| Trustful neighbourhood | ||||||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.68 | 1.21 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 1.24 |

| Helpful neighbourhood | ||||||

| Yes | 1.17 | 0.88 | 1.56 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 1.61 |

| Cooperative neighbourhood | ||||||

| Yes | 1.50*** | 1.18 | 1.89 | 1.22 | 0.96 | 1.56 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

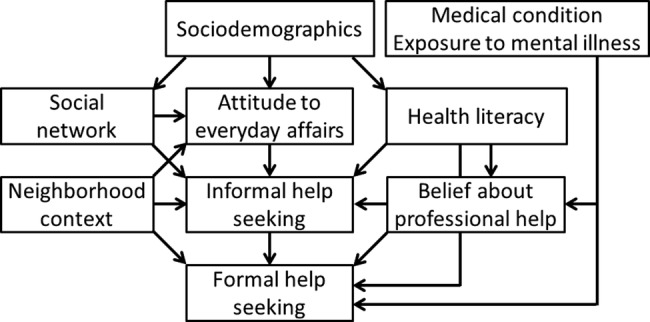

Figure 2 shows the results of path analysis. After trimming paths with non-significant contributions, the final model resulted in a better fit to the data (GFI 0.946; AGFI 0.918; RMSEA 0.072, 90% CI 0.068 to 0.075). An informal help-seeking intention had the greatest direct effect on a formal help-seeking intention. Besides this, psychiatric history, health literacy, perceived effectiveness of professional help and communicative neighbourhood had a direct effect on a formal help-seeking intention. Tendency to consult about everyday affairs and cooperative neighbourhood had an indirect effect on a formal help-seeking intention through its effect on an informal help-seeking intention.

Figure 2.

Path diagram for help-seeking intentions for mental illness. Rectangles were observed variables. Ellipses were latent variables. Values on the single-headed arrows were standardised regression weights. Values on the double-headed arrows were correlation coefficients. Model fitness: GFI 0.946; AGFI 0.918; RMSEA 0.072 (90% CI 0.068 to 0.075). AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; GFI, goodness of fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

Discussion

Causal effect of neighbourhood context, or neighbourhood effect, has been reported on various health outcomes including mental illness, whereas the methodology for estimating neighbourhood effects, including definitions of neighbourhood, measures of neighbourhood context and analytical models, varies widely across studies.21 22 In the absence of established methodology, this study examined four specific features of neighbourhood context relevant to neighbourhood social capital and their associations with help-seeking intentions for mental illness. A number of studies have been conducted to identify the individual factors that may inhibit or facilitate help-seeking for mental illness, but less is known about the neighbourhood factors. Moreover, to date, there have been few attempts to elucidate multifactorial mechanisms for help-seeking using structural equation modelling. This is the first study to illustrate the pathways linking individual and neighbourhood factors to informal and formal help-seeking intentions and bore out the hypothesis that neighbourhood context contributes to help-seeking intentions for mental illness.

The final structural equation model (figure 2) along with the results of multiple logistic regression analysis revealed the individual and neighbourhood factors that may directly or indirectly affect help-seeking decision-making. The neighbourhood factors showed a relatively modest but significant effect compared to the individual factors. These results support the expectation that neighbourhood context, or more specifically neighbourhood social capital, may exert influence on help-seeking for mental illness, as it does on other health behaviours.7 Moreover, the significant positive effect of communicative neighbourhood seems to confirm the power of daily interactions with weak ties.23 People who often interact with weak ties are more likely to have a sense of belonging and thus less likely to hesitate to seek help from people around them. Creating a neighbourhood with a communicative atmosphere may be worth considering as a possible public health strategy for encouraging help-seeking.

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, the highest ORs for informal and formal help intentions were found in tendency to consult about everyday affairs and perceived effectiveness of professional help, respectively. In the path analysis, tendency to consult about everyday affairs and health literacy were represented as a key player in help-seeking decision-making. Tendency to consult about everyday affairs seems to depend largely on personality, so that it may be difficult to achieve drastic changes in this factor using a public health approach. In contrast, health literacy skills can be developed through community-based educational outreach.24 Improved health literacy will contribute to a better understanding of the effectiveness of professional help, which will increase the probability of formal help-seeking.12 Developing health literacy skills may be worth considering as another possible public health strategy for encouraging help-seeking.

The multiple logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between sociodemographics and help-seeking intentions, except between marital status and informal help-seeking intention. Meanwhile, the path analysis showed that male gender, older age, unmarried status, lower education and lower income were associated with decreased likelihoods of help-seeking intentions through their effects on tendency to consult about everyday affairs and health literacy. More attention should be paid to these high-risk groups when implementing public health strategies for encouraging help-seeking.

This study provides the first step towards understanding the role of neighbourhood in the help-seeking process; however, it has a number of potential limitations. First, the study participants were recruited from a nationwide panel of an online research company. As described in the Methods section, the study participants included twice as many highly educated people as in the Japanese population. Although we confirmed that the distribution of HLS-14 scores in the study participants was quite similar to that obtained from our previous paper-based survey in Japanese healthcare facilities,25 the selection bias may have influenced the results to some extent. Second, the method of measuring help-seeking intentions was based on the most commonly used methodology,9 but its validity has not been confirmed yet. Participants were asked to imagine themselves with serious mental illness and then report their help-seeking intentions. Because no detailed description was given, their answers depended on how they imagined the severity of the condition. Previous studies suggested that the probability of formal help-seeking for mental illness depends on severity of illness.18 26 27 The percentages of informal and formal help-seeking intentions, and the magnitude of individual and neighbourhood factors, may vary with different severity assumptions. Third, although the final structural equation model revealed an acceptable fit to the data, it still leaves room for further improvement. The HLS-14 and the LSNS-6 were validated in Japanese people,11 14 but the other instruments used in the survey were not. Neighbourhood physical environments such as population density and healthcare resources, which can affect mental health,22 were not included in the analysis. Fourth, the study design is cross-sectional and self-reported, so we cannot reject the possibility of reverse causation or common method bias. Further studies are needed to provide definitive evidence for the role of neighbourhood in the help-seeking process and to elucidate in more detail multifactorial mechanisms for help-seeking. Moreover, the relationship between help-seeking intentions and actual help-seeking should be investigated in future.

Conclusion

Help-seeking intentions for mental illness were directly associated with neighbourhood context as well as individual characteristics. Especially note that living in a communicative neighbourhood and having adequate health literacy were acknowledged as possible facilitating factors for both informal and formal help-seeking for mental illness. The effectiveness of efforts to increase help-seeking may be limited if only interventions targeted to individual factors are implemented. It may be worth attempting to incorporate community-based interventions for creating a neighbourhood with a communicative atmosphere and those for developing health literacy skills into public health strategies for encouraging help-seeking or suicide prevention policies.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS was responsible for the design and conduct of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and the writing of the article. TY and HS contributed to the data interpretation and discussion of the implications of this work.

Funding: This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 25460815).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine and has been conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies by the Japanese Government.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014 (accessed 1 June 2015).

- 2.Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Hwang I et al. . Treatment of suicidal people around the world. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:64–70. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z et al. . Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med 2014;44:1303–17. 10.1017/S0033291713001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaren L, Hawe P. Ecological perspectives in health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:6–14. 10.1136/jech.2003.018044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui A, Wong P, Fu KW. Building a model for encouraging help-seeking for depression: a qualitative study in a Chinese society. BMC Psychol 2014;2:9 10.1186/2050-7283-2-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen IH, Syme SL. The social environment and health: a discussion of the epidemiologic literature. Annu Rev Public Health 1999;20:287–308. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuel LJ, Commodore-Mensah Y, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Developing behavioral theory with the systematic integration of community social capital concepts. Health Educ Behav 2013;41:359–75. 10.1177/1090198113504412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. National Census 2010. http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL08020103.do?_toGL08020103_&tclassID=000001038689&cycleCode=0&requestSender=estat (accessed 1 Jun 2015). Japanese.

- 9.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J et al. . Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counseling 2005;39:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans-Lacko S, Rose D, Little K et al. . Development and psychometric properties of the reported and intended behaviour scale (RIBS): a stigma-related behaviour measure. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2011;20:263–71. 10.1017/S2045796011000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suka M, Odajima T, Kasai M et al. . The 14-item health literacy scale for Japanese adults (HLS-14). Environ Health Prev Med 2013;18:407–15. 10.1007/s12199-013-0340-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Have M, de Graaf R, Ormel J et al. . Are attitudes towards mental health help-seeking associated with service use? Results from the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:153–63. 10.1007/s00127-009-0050-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G et al. . Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006;46:503–13. 10.1093/geront/46.4.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurimoto A, Awata S, Ohkubo T et al. . Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 2011;48:149–57. Japanese 10.3143/geriatrics.48.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji I, ed. Health Survey of People Affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake in Miyagi Prefecture (MHLW Grant Research Report 2013). Center for Community Health, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 2014. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths KM, Crisp DA, Barney L et al. . Seeking help for depression from family and friends: a qualitative analysis of perceived advantages and disadvantages. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:196 10.1186/1471-244X-11-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakamoto S, Tanaka E, Neichi K et al. . Where is help sought for depression or suicidal ideation in an elderly population living in a rural area of Japan? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004;58:522–30. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rüdell K, Bhui K, Priebe S. Do ‘alternative’ help-seeking strategies affect primary care service use?: a survey of help-seeking for mental distress. BMC Public Health 2008;8:207 10.1186/1471-2458-8-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, third edition. New York: Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald RP, Ho MH. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods 2002;7:64–82. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:125–45. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truong KD, Ma S. A systematic review of relations between neighborhoods and mental health. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2006;9:137–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandstrom GM, Dunn EW. Social interactions and well-being: the surprising power of weak ties. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2014;40:910–22. 10.1177/0146167214529799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:2072–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suka M, Odajima T, Okamoto M et al. . Relationship between health literacy, health information access, health behavior, and health status in Japanese people. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:660–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorm AF, Griffiths KM, Christensen H et al. . Actions taken to cope with depression at different levels of severity: a community survey. Psychol Med 2004;34:293–9. 10.1017/S003329170300895X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown J, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L et al. . Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:275 10.1186/s12888-014-0275-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]