Abstract

Objective

Synthesise evidence about the impact of family medicine/general practice (FM) clerkships on undergraduate medical students, teaching general/family practitioners (FPs) and/or their patients.

Data sources

Medline, ERIC, PsycINFO, EMBASE and Web of Knowledge searched from 21 November to 17 December 2013. Primary, empirical, quantitative or qualitative studies, since 1990, with abstracts included. No country restrictions. Full text languages: English, French, Spanish, German, Dutch or Italian.

Review methods

Independent selection and data extraction by two authors using predefined data extraction fields, including Kirkpatrick’s levels for educational intervention outcomes, study quality indicators and Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) strength of findings’ grades. Descriptive narrative synthesis applied.

Results

Sixty-four included articles: impact on students (48), teaching FPs (12) and patients (8). Sample sizes: 16-1095 students, 3-146 FPs and 94-2550 patients. Twenty-six studies evaluated at Kirkpatrick level 1, 26 at level 2 and 6 at level 3. Only one study achieved BEME’s grade 5. The majority was assessed as grade 4 (27) and 3 (33). Students reported satisfaction with content and process of teaching as well as learning in FM clerkships. They enhanced previous learning, and provided unique learning on dealing with common acute and chronic conditions, health maintenance, disease prevention, communication and problem-solving skills. Students’ attitudes towards FM were improved, but new or enhanced interest in FM careers did not persist without change after graduation. Teaching FPs reported increased job satisfaction and stimulation for professional development, but also increased workload and less productivity, depending on the setting. Overall, student’s presence and participation did not have a negative impact on patients.

Conclusions

Research quality on the impact of FM clerkships is still limited, yet across different settings and countries, positive impact is reported on students, FPs and patients. Future studies should involve different stakeholders, medical schools and countries, and use standardised and validated evaluation tools.

Keywords: MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, Family Medicine, Clerkship, Impact, Undergraduate medical education

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Systematic review of 64 studies on the impact of family medicine/general practice clerkships on medical students, teaching general/family practitioners and/or their patients, from 1990 to 2013, without country limitations.

Comprehensive search strategy using the major databases for medical and educational research and following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Studies assessed for research quality, Kirkpatrick’s levels of educational outcomes and Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME)’s grades of strength of findings.

Lack of meta-analysis due to variety of study designs, evaluation tools and outcomes and the reported results.

Despite the comprehensive search strategy, due to full-text language and accessibility limitations, other studies published in this research area may have been missed.

Introduction

In the past few decades, family medicine/general practice (hereafter FM) has developed into a clinical and academic discipline aiming to provide comprehensive and quality patient care, and to contribute to medical research and education.1–4 As a primary care discipline with an untapped potential for contribution to medical education, FM has played an important role in the trend of the past few decades to orient medical school curricula toward community-based health services alongside those traditionally hospital-based.5–7 In light of the increasing need to address complex and multiple chronic conditions in ageing societies, and the recognition of the complementary roles of hospital and primary care, current recommendations call for more exposure of medical students to primary care and FM as its core medical specialty.8–10

The contribution of FM in the undergraduate medical curriculum is multifaceted, reflecting the broadness and comprehensiveness of the specialty itself. In the junior/preclinical years, FM may provide early exposure to patients, introducing students to the doctor–patient relationship and the influence of illness in families, as well as teaching on communication and clinical skills. During the senior/clinical years, the main contribution is teaching about the specialty of FM by either block or longitudinal clinical experiences (clerkships) or providing shared experiences of primary and secondary/tertiary care with other specialties.6 11–14

Yet, the level of involvement and contribution of FM in undergraduate medical education varies in different countries, depending on its scope of practice and role in the healthcare system, as well as its academic status. The EURACT (European Academy of Teachers in General Practice and Family Medicine) has recently mapped the availability of FM clerkships in all European schools through a survey of 259/400 medical schools in 39 European countries, revealing variability between European regions regarding the availability, length and scope of FM clerkships.15 Fifty medical schools, mostly in Southern and Eastern Europe, reported either a lack of or only very brief FM clerkships.15

Previous reviews on ambulatory care teaching and learning experiences in North America that included studies on both undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in internal medicine, FM, paediatrics or other ambulatory care specialties until 1999, have confirmed their positive educational contribution, yet called for further and more rigorous research, especially on learning outcomes.16–18 Recent reviews on longitudinal integrated clerkships, placements of students in rural and underserved areas, and mapping the contribution of undergraduate ambulatory education to the Canadian recommendations for undergraduate medical education have included learning experiences in FM clerkships.19–21 Yet to our knowledge, no published systematic review so far has focused specifically on the impact of FM clerkships and extended beyond North America.

We perceive there is a need for such a systematic review, in light of the previously reported valuable educational opportunities of ambulatory undergraduate education in North America and the current limited availability of FM clerkships in some parts of Europe and internationally.1 15

The aim of this review is to search, analyse and synthesise evidence about the impact of FM clerkships on learning outcomes of undergraduate medical students, general/family practitioners (hereafter FPs) who host the students in their practices, as well as on their patients.

Methods

This systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.22

Selection criteria

The included papers involved undergraduate medical students, teaching FPs or patients in FM clerkships, as participants. FM clerkships were defined as structured periods of clinical experiences in FM to learn about the FM specialty, during which students work with patients, under supervision of a preceptor/tutor, and attend didactic sessions delivered by FM faculty.23 These clerkships might be either a block of several weeks or longitudinal experiences spread throughout the whole semester/year. The outcomes of studies included in this review were the impact of FM clerkships on the education of the participating students, the work of the teaching FPs, and/or on their patients. The adapted Kirkpatrick levels for educational intervention outcomes were used to assess the impact of the FM clerkship on the education of students.24 Kirkpatrick's levels 1 and 2 consider students’ views on the learning experience of the FM clerkship (1), changes in attitudes towards FM (2A), and knowledge and/or skills (2B), as a result of the clerkship. Level 3 involves transfer of learning to practice, while level 4 considers changes in organisational practice (4A) or benefits to patients (4B) as a direct result of the learning during the FM clerkship.

The review’s selection criteria were discussed and agreed among three of the reviewers (ET, RR and NM; table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Medical students | Other healthcare students (nursing, dentistry pharmacy, veterinary, etc) |

| Undergraduate education | Postgraduate education | |

| Clinical years | Preclinical/bachelor years (year 1–2/3) | |

| Intervention | Clinical experience focused in FM as a discipline | Clinical experience in primary care or FM not focused in FM as a discipline |

| Type of study | Empirical studies (quantitative or qualitative) | Non-empirical studies (editorials, news, reports) |

| Other | Abstract available | No abstract available |

| Year of publication >1990 | Year of publication <1990 | |

| Any country | No exclusion by country | |

| Full text available in English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish or Italian | Full text in any other language or not available |

FM, family medicine/general practice.

All empirical quantitative or qualitative studies from 1990 onward, with available abstracts and primary data on the impact of FM clerkships on medical students, teaching GP/FPs and/or patients, were included. No restrictions were applied on country, but full text languages were limited to English, French, Spanish, German, Dutch or Italian (languages spoken by reviewers).

Studies that focused on some other specific features of teaching and learning in FM such as rural versus urban setting, introduction of specific teaching or assessment methods, as well as those assessing students’ clinical exposure during preclinical/junior years, were excluded.

Search strategy

The essential concepts used for the search strategy were: general practice/FM/primary care (discipline/practice and practitioners) and clinical clerkships/attachments/rotations/placements/clinical experiences/preceptorships. Medline (via Ovid), ERIC, PsycINFO, EMBASE and Web of Knowledge were searched from 21 November to 17 December 2013. The search syntax used a combination of terms for key concepts adapted to each database (see online supplementary appendix). Additional relevant studies were identified based on expert knowledge of the reviewers.

Study selection

Two reviewers (ET and RR or NRM) independently screened titles and abstracts selecting those that met inclusion criteria. The full-texts of the selected articles were independently assessed against the search criteria by two reviewers (ET and RR or NRM). In case of disagreement or uncertainty, the reviewers discussed and when necessary the opinion of a third reviewer was considered for the final decision.

Data extraction and analysis

One of the reviewers (ET) extracted data from each full-text article using a purpose-designed data extraction form based on the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) coding form.25 26 A second reviewer (RR, NRM or KH) checked the extracted data. In case of disagreement, the opinion of a third reviewer was used for the final decision.

Extracted data focused on the clerkship (country, setting, location in the curriculum, duration, aims and objectives) and study methodology (design, data sources, population and measured outcomes). The methodology rigour of studies was evaluated with a checklist adapted from a previous medical education systematic review.26 The strength of findings for each study was scored on the BEME scale of 1–5:25

Grade 1: No clear conclusions can be drawn; not significant

Grade 2: Results ambiguous, but there appears to be a trend

Grade 3: Conclusions can probably be based on the results

Grade 4: Results are clear and very likely to be true

Grade 5: Results are unequivocal.

Owing to the variety of measured outcomes, methods and tools, methodological quality and reported statistics of the included studies, meta-analysis was not possible. Descriptive narrative synthesis was used for the analysis and synthesis of the findings.27 The synthesis will report on the types of FM clerkships in terms of duration, location in curriculum, setting and learning aims and objectives; studies’ countries and year of publication, evaluation methods, Kirkpatrick outcome evaluation level, methodological quality and the main findings related to the impact of FM clerkships on medical students, teaching FPs and/or their patients.

Results

Search results

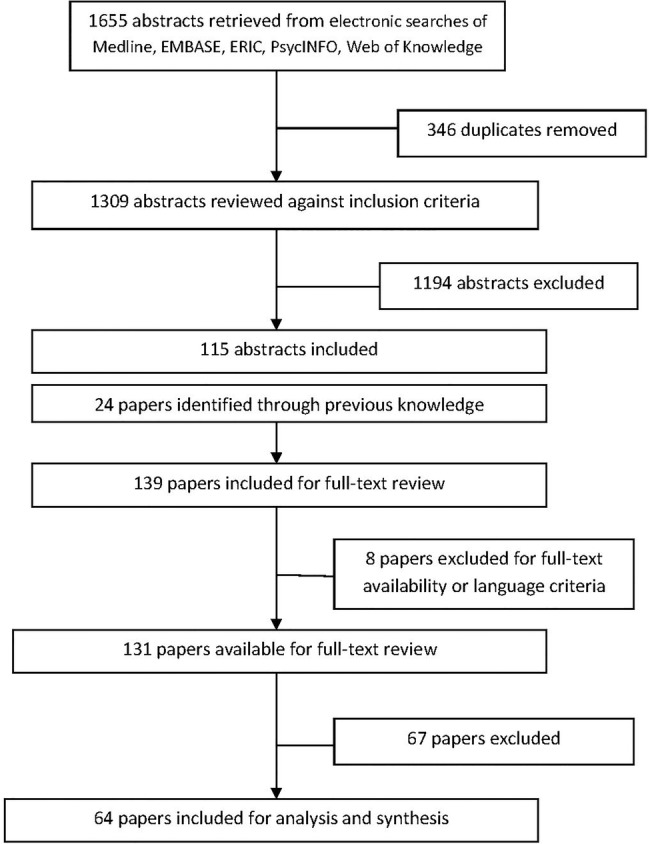

The search strategy identified 1655 papers, which were entered in Endnote X6 (figure 1). After de-duplication and screening of titles and abstracts, 1540 papers were excluded mainly because they focused on other aspects of FM involvement in medical education, non-educational aspects of FM or postgraduate FM. Four papers selected for full-text review were not available even after using inter-university library exchange, while four others were available only in Chinese, Norwegian or Hebrew.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the process of search and selection of the papers.

After full-text review, 64 papers were selected for data extraction and analysis. The main reasons for exclusion at this stage were clerkship not focused on the discipline of FM, population being preclinical or not clearly clinical students or the clerkship’s impact was not the study’s main focus.

Study characteristics

Out of the 64 included studies, 56% were published from 1990 to 2000, and the majority were from the USA (30 studies) and Europe (21 studies; table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of reviewed studies by country and publishing year intervals

| Number of studies by year intervals |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 1990–2000 | 2001–2010 | 2011–2013 |

| USA | 23 | 7 | 0 |

| UK | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Sweden | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ireland | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| The Netherlands | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Germany | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Austria | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Israel | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Turkey | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pakistan | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| United Arab Emirates | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Australia | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hong Kong | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| South Africa | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 36 | 24 | 4 |

Forty-eight studies reported the impact of FM clerkships on students, 12 on teaching FPs and their practices and 8 on patients involved in FM clerkship teaching. Three studies had a mixed target population of students, FPs and/or patients.28–30

Thirteen studies were non-randomised controlled studies and 12 were pre–post (uncontrolled) studies (table 3). The sample size ranged from 16 to 1095 students, 3 to 146 teaching FPs and 94 to 2550 patients. The methods used to evaluate the impact of FM clerkships were mostly questionnaire surveys (36 studies) and patient encounter forms/logs of students or coding/billing forms of FPs (13 studies) (table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of reviewed study by design and data sources

| Study design | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Non-randomised controlled | 13 |

| Uncontrolled (pre–post clerkship) | 12 |

| Post-clerkship only | 5 |

| Longitudinal | 4 |

| Descriptive with statistical analysis | 22 |

| Descriptive only | 7 |

| Action research | 1 |

| Data sources | |

| Questionnaires | 36 |

| Interviews | 6 |

| Focus groups | 5 |

| Patient encounter forms | 12 |

| Coding/billing forms | 1 |

| Oral examination | 1 |

| Written examination | 2 |

| Clinical examination (OSCE) | 1 |

| Self-assessment forms | 4 |

| Direct observation | 3 |

| Specialty selection records | 6 |

OSCE, objective structured clinical examination.

Clerkship format

FM clerkships varied considerably in duration and setting. The duration ranged from 2 to 12 weeks, with one study reporting on a year-long longitudinal clerkship,31 while in eight papers the duration of the clerkship was not clearly stated. The setting was mainly mixed (urban and rural) for 23 studies, urban for 9 and rural for 1 study,32 while for 31 studies the setting was not clearly stated. The clerkships were mainly obligatory (56 studies) and took place in year 3 (27 studies in USA), years 4–5 (10 studies) or years 5–6 (22 studies), while three studies did not clearly report the curriculum year of the clerkship. The aim and goals of the clerkships were reported only in nine papers33–41 and included: providing exposure to the role of FM and primary care as a medical practice setting and assisting students in making their career decision; refining and consolidating history taking and physical examination skills in the FM setting with a special emphasis on communication skills, and the doctor–patient relationship; dealing with most common medical problems in FM and its specific management principles such as undifferentiated problems, home visits, referrals, etc; learning about business/organisational aspects of the medical practice and the role of team-work.

Kirkpatrick outcome levels

Table 4 summarises the proportion of studies that assessed the impact of FM clerkships at each Kirkpatrick outcome level.

Table 4.

Distribution of reviewed studies by Kirkpatrick outcome levels and strength of findings

| Kirkpatrick outcome levels | Studies (n) |

|---|---|

| 1: Reaction | 26 |

| 2A: Learning—change in attitudes | 12 |

| 2B: Learning—change in knowledge and skills | 13 |

| 3: Change in behaviours | 6 |

| 4A: Results-change in the system/organisational practice | 0 |

| 4B: Change in patient care outcomes | 0 |

| Strength of findings | |

| Grade 1: No clear conclusions can be drawn; not significant | 0 |

| Grade 2: Results ambiguous, but there appears to be a trend | 3 |

| Grade 3: Conclusions can probably be based on the results | 33 |

| Grade 4: Results are clear and very likely to be true | 27 |

| Grade 5: Results are unequivocal | 1 |

Twenty-six (41%) studies reported students’ views on the quality of the clerkship (level 1), while the rest of the studies reported changes in attitudes, knowledge/skills or behaviours (levels 2 and 3). Although none of the reviewed studies reported the evaluation of the transfer of students’ learning during FM clerkships into their workplace, we included, under Kirkpatrick level 3, six studies that followed up and reported the entrance of graduates in FM specialty training considering it as an application of their learning about FM during the clerkship. None of the reviewed studies reported effects on the system/organisation or patient care outcomes as a direct result of the knowledge, skills and attitudes gained by students in the FM clerkship (level 4).

Methodological quality

Table 4 reports the number of studies in each of the five grades of strength of findings. The majority of studies were grade 3 (52%) or 4 (42%). Only one study was graded as 5 (unequivocal results).42 The quality criteria that were most commonly unclear or not met included accounting for multiple variables/factors, generalisability of conclusions, addressing relevant ethical issues as well as using data from more than one source.

Synthesis of findings on the impact of FM clerkships

Impact on students

Table 5 provides information about each study that evaluated the impact of the FM clerkship on students for each Kirkpatrick outcome level.

Table 5.

Studies reporting impact of FM clerkships on students according to Kirkpatrick outcome levels

| Kirkpatrick level 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year) | Country | Clerkship features | Study methods | Key findings | Strength Grade |

| Bahn et al (2003)43 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs for clinical exposure and student involvement; (RR 87/105; 2591 encounters FM and 2527 IM); students report 30 patients for FM and 30 for IM; 7–8 patients/week not on same day | Similar exposures for 5/10 diagnoses in FM and IM; encounters students ‘observed only’ lower in FM (15%) vs IM (19%) p<0.001; students conducted PE more often in FM (77%) vs IM (73%) p<0.001 | 4 |

| Carney et al (2000)44 | USA | Y 3; 8 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs for cases encountered and level of observation/feedback by tutor (RR 63/63 students; 4083 encounters=3221 patients); students reported 1 full day/week | Exposure: acute care (39%), health maintenance visit (27%), chronic diseases (21%) and their acute exacerbations (13%); 63% performed Hx taking and 48% PE unobserved; in 49% of encounters students received no feedback | 3 |

| Carney et al (2002)45 | USA | Y 3; 8 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs for cases encountered and level of observation/feedback by tutor (RR 15 759 cards/?; 59% FM, 22% Ped, 12% IM); validity and reliability of the forms reported (κ coeff 0.68) | Students in FM had more continuity visits (18% of visits vs 11% each for IM and Ped); behaviour change counselling, clinical procedures as well as a better mixture of chronic and acute visits; in FM student did more Hx taking (61%) and PEs (47%) by themselves (unobserved); they received more feedback and teaching on diagnosis and management during IM clerkship | 3 |

| Cullen et al (2004)58 | Ireland | Y 5/6; ? weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs for cases and involvement of two cohorts of students (RR 186/227; 3710 consultations); students reported 20 consecutive patients on day 5 of clerkship | In 53% of visits student observed the FP; in 12% took Hx; in 32% did PE; in 12% did a procedure/investigation; 78% of visits were with adults and 18% of them were elderly (≥66 years old) | 3 |

| Schamroth et al (1990)48 | UK | Y 4; 3 weeks; O; urban | Patient encounter forms and activity logs (RR 48/84) | 85% of time is spend observing passively; 69% of cases discussed with tutor; average 19 patients/day and median one home visit/day; highly rated (3/4) usefulness and stimulation effect of the FP tuition | 3 |

| Chenot et al (2009)52 | Germany | Y 5; 2 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (mandatory and web based); 2 cohorts (RR 695/695) | Satisfaction with clerkship 8.1/10; contributions: recognition of frequent health problems (85%), communication (65%) and PE skills (61%); majority had home visits (95%); did supervised PE (94%) and Hx taking (89%) | 3 |

| Cooper (1992)61 | Australia | Y 4/5; 2 weeks; mixed setting | Post-clerkship questionnaires; retrospective analysis of 2 cohorts (RR 386/398) | Satisfaction: 68.6% excellent/very good; contributions: variety of problems encountered (39.2%), experience in managing common problems (33.5%); performing practical procedures (24.8%); qualities of FM teaching: willing to answer question (46%), set aside time to discuss (32%), enthusiasm, welcoming and friendly (52.1%) | 3 |

| Foldevi (1995)34 | Sweden | Y 4 and 5; 5 weeks; O; mixed setting | Post-clerkship questionnaires (RR 85/115); factor analysis of questionnaires items reporting good construct validity | Satisfaction: overall rating 79±23/100; quality of tutoring 79±18/100; feedback: 45±14/100; student responsibility: 47±11/100 | 4 |

| Iqbal (2010)59 | Pakistan | Y 3; 2 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (RR 46/46) | Most important things learned: confidence to deal with common health problems, empathy and communications skills | 3 |

| Kalantan et al (2003)36 | Saudi Arabia | Y 5 and 6; 6 weeks; O; urban | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (RR 177/177) | Best things: friendly welcoming attitude of FP and staff (92%), gaining experience in managing common clinical problems (87.6%) and insight in FP life (86.4%); 59.3% expected more from the FM clerkship in regard to practical procedures, involvement in consultation and time for discussion; quality of FM teaching: willing to answer questions (82%), set aside time to discuss (56.5%), encouraged me to ask questions (61%), friendly and welcoming (93.2%) | 4 |

| Kavukcu et al (2012)53 | Germany | Y 6; ? weeks; O | Post-clerkship DREEM questionnaires to FM and Sports medicine clerkships in a primary care centre (RR 55/55 each) | DREEM score for FM 139.45/200 and sports medicine 140.05/200 p<0.05; overall score 140/200 of the out-of-hospital educational environment | 3 |

| Rabinowitz (1992)38 | USA | Y3; 6 weeks; O; mixed setting | Post-clerkship questionnaires; 3 cohorts (RR 850/?) | FM highest rated clerkship among all required clerkships (no numbers reported) | 2 |

| Morrison and Murray (1996)49 | UK | Y final; 4 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaire (RR 131/206) | 4% (pre) to 47% (post) had FM as their 3 most enjoyed subjects | 4 |

| Svab and Petek-Ster (2008)40 | Slovenia | Y final; 8 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires; 2 cohorts 10 years apart (RR 127/172 pre and 123/140 post) | Satisfaction: 8.73±0.93/10 at first cohort and 9.04±0.93/10 at second cohort; p=0.035 | 4 |

| Vinson and Paden (1994)46 | USA | Y3/4; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Post-clerkship questionnaires (RR 43/46) | Quality of feedback: good/excellent in 14/15 practices that did not consider clerkship as recruiting tool; in the rest (31) practices quality of feedback: fair/poor | 3 |

| Sprenger et al (2010)30 | Austria | Y 6; 5 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaires (RR 146/146) | 87% ‘strongly agree’ and 13% ‘agree’: clerkship was overall positive experience; 79% ‘ideal supervision’, 82%: tutor’s expertise excellent | 4 |

| McKee et al (1998)28 | USA | Y 3; 6 weeks; O; urban | Daily activity logs and quality scores; students and preceptors at community health centres; (RR 14/16; 232 sessions) | Quality of learning: 63/100; not correlated to clinical productivity of preceptors; students saw independently 2.52±1.71 out of 4.45±3.34 pts/session and received feedback 2.44±2.76 times/session; students quality rate higher (63) than preceptors (54) p=0.003, but only 62/232 sessions were matched student-preceptor | 3 |

| Lloyd and Rosenthal (1992)50 | UK | Y 4; 4 weeks; O; urban | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (RR 70/95) | Scores of achievement areas (post) < scores of expectations (pre); psychological and social aspects of disease, communication skills, clinical decision-making skills and management plans had higher achievement scores (although < expectations); PE skills, taking blood and performing a PAP smear had lower scores; 57% report gaining insight in the FP's work and life and knowledge content of FM as main contributions | 4 |

| Senf and Campos-Outcalt (1995)47 | USA | Y3; 6 weeks; O; mixed setting | Pre–post questionnaires; 10 cohorts (RR 997/1095); post-clerkship evaluation | 54.1%: FM clerkship ‘somewhat’ or ‘a lot’ better than previous clerkships | 4 |

| Sprenger et al (2008)54 | Austria | Y 6; 5 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaire (RR 30?/?) | Very positively rated by students (visual scale shown, but rating not clear) | 2 |

| Svab (1998)57 | Slovenia | Y 6; 7 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaires (RR 135/175) | 73%: favourable score on cooperation with tutor; highest score for learning on record keeping, referrals and prescribing | 3 |

| Peleg et al (2005)55 | Israel | Y 5; 6 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaires; 2 cohorts (RR 186/186 and 176/186) | Mean evaluation and satisfaction score: 3.4/4; ranked high among other clerkships (no numbers reported) | 3 |

| Mash and de Villiers (1999)60 | South Africa | Y final; 2 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaire and focus group (RR 108/121) | 7.8/10 ‘useful and relevant’; 59% of the material covered: new/not duplicate of previous teaching; focus group themes: patient-centeredness and continuity of care, management of common and undifferentiated problems, holistic assessments, communication skills, primary care team | 3 |

| Dahan et al (2001)56 | Israel | Y 6; 5 weeks | Post-clerkship questionnaire and focus group; 2 cohorts (RR 49/80 and 52/80); 2 years before and after organisation and content change of clerkship | Satisfaction score improved from 85 to 97/100 | 3 |

| Mattsson et al (1991)51 | UK | Y final; 2 weeks; O | Post-clerkship interviews (RR 20/20); 10 with higher and 10 lower grades and tutors’ comments | Appreciated contributions: focus on communications skills, whole person care and continuity of care | 3 |

| Snaddena and Yaphe (1996)39 | UK | Y 4; 4 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaire, interviews and focus group (RR 75/75) | Overall experience: 4.78/5; wide range of clinical experiences, home visits, preventive medicine, referrals, learning communication skills, seeing the patient as a person not as a disease, insight in organisation of FM centre and staff; friendly atmosphere; good level of tutoring (students want more seeing of patients alone then observing) | 3 |

| Kirkpatrick level 2A | |||||

| Dixon et al (2000)33 | Hong Kong | Y final; 2 weeks; O | 15 post-clerkship focus groups (RR 110/110) | Previous negative stereotypes of FPs (easy and boring job and making lots of money) changed into understanding that FM is not boring and has its own diagnostic challenges | 3 |

| Iqbal (2010)59 | Pakistan | Y 3; 2 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (RR 46/46) | Increase in those interested in future FM career (7% pre to 37% post); those ‘not sure’ reduced (69% pre to 43% post); those already decided for ‘no' (24% pre to 20% post) | 3 |

| Kruschinski et al (2011)63 | Germany | Y 5; 3 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (RR pre 287/423 and post 165/287) | Post-clerkship more positive attitudes toward FM as a discipline; no significant change in future career plans; gender more influential on future career choices than attitudes | 4 |

| Lloyd and Rosenthal (1992)50 | UK | Y 4; 4 weeks; O; urban | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires (RR 70/95) | ∼65%: clerkship changed their attitudes toward FM: 48% in favour, 14% against and 40% neutral; 37%: clerkship had influence on career intentions: 63% in favour; 25% against and 12% neutral | 4 |

| Maiorova et al (2008)64 | The Netherlands | Y 5/6; 12 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires in three clerkship: FM (RR 168/206), internal medicine (RR 247/347), surgery (RR 178/378) | Increased perceived likelihood of choosing a specialty after the clerkship: FM (29%), IM (30%) and surgery (31%); majority had no change (63%, 49%, 59% respectively) | 3 |

| Morrison and Murray (1996)49 | UK | Y final;4 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires; postal questionnaire 1 year after graduation (16–26 months after clerkship) (RR 131/206) | % of students likely to choose FM career: 38.8% pre to 53.5% post clerkship; those unlikely: 18.6–13.2%; 1 year after graduation only 34.9% likely and 24.8% unlikely to choose FM | 4 |

| Musham and Chessman (1994)65 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O | Post-clerkship focus groups (RR 122/122) | Negative pre-clerkship stereotype ‘FM=low status and intellectually unchallenging’ changed to ‘FM intellectually challenging and not inferior to other specialties’; increased interest in FM career for those who had not decided yet | 3 |

| Paulman and Davidson-Stroh (1993)32 | USA | Y 4; 8 weeks; O; rural | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires on specialty preferences and data on final specialty selection; 4 cohorts of students (RR 598/598) | No change of career interests: 78.1% (other specialties) and 16.4% (FM); 3.8%:positive shift of interest toward FM; 1.7%: negative shift | 4 |

| Sadikoglu et al (2006)66 | Turkey | Y final; 4 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires on specialty choices (RR 90/93) | Statistically significant increase in ranking of FM as a career choice: 4.19±0.10 pre to 3.88±0.10 post; pre–post change in attitude toward FM as a career: not significant | 3 |

| Senf and Campos-Outcalt (1995)47 | USA | Y 3; 6 weeks; O; mixed setting | Pre–post clerkship questionnaire on attitudes and specialty preferences, and data on final specialty selection; 10 cohorts of students (RR 997/1095) | Unchanged specialty preferences: 66% (other specialties) and 18% (FM); 4%: negative change of preferences; 12%: positive; 8% net increase of interest in FM | 4 |

| Svab and Petek-Ster (2008)40 | Slovenia | Y final; 8 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires of two cohorts between 10 academic years (RR 127/172 pre and 129/140 post) | Statistically significant positive changes in scores of attitudinal statements on role and importance of FM; no stat significant increase in preferences for FM careers pre–post clerkship and between 10 years | 4 |

| Tai-Pong (1997)67 | Hong Kong | Y 4/5; 2 weeks; O | Post-clerkship questionnaires and 1 year after graduation (18–26 months after clerkship) (RR 88/138) | At 18–26 months: 54% ‘clerkship had positively changed their attitudes towards FM’; 27% ‘it had positively changed their decision to pursue a FM career’; 10% had negative change | 3 |

| Kirkpatrick level 2B | |||||

| Beasley et al (1992)71 | USA | Y 3; 2–3 months; E | National board of medical examiners (NBME) part 2 examination scores of 95 students who took FM clerkship and two control groups (similar NBME 1 scores) who did not take clerkship | No statistically significant difference in scores of medicine and surgery parts of examination; those with FM clerkship significantly higher scores only in public health items | 4 |

| Gjerde et al (1997)72 | USA | Y 3; 2 weeks; O; mixed setting | Students’ self-report on involvement during the clerkship (checklist of skills, diagnoses and procedures); 3 cohorts (RR 486/486) | Actively performing well-baby examination (72%), managing upper respiratory infections (85%), acute otitis media (81%), sinusitis (70%) and sore throat (70%), performing breast (64%), pelvic and PAP smear (59%), prostate (58%) examinations and laceration suturing (52%) | 3 |

| Gjerde et al (1998)35 | USA | Y 3; 2–3 weeks; O; mixed setting | Pre–post clerkship students’ self-report on involvement during clerkship (checklist of skills, diagnoses and procedures) (RR 87/87) | >50% actively performed/managed only after the FM clerkship: preventive skills (5/10 skills), acute sprain/strain, low back pain, sinusitis, strep throat, acute bronchitis and osteoarthritis (6/31 diagnoses), removal of foreign body from eye, incision and drainage of external haemorrhoids’ thrombosis and infant circumcision (3/39 procedures) | 4 |

| Jacques (1997)73 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O | Written examinations (MCQs) scores between two schools with different clerkship schedules (RR school A 232/232; school B 188/188) | Increase of scores after clerkship: school A 63.4% pre—82.6% post=19%; school B 2 65.5% pre-80.5% post=15%; no significant difference between schools with different system of clerkships’ scheduling | 3 |

| Maple et al (1998)37 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Pre–post clerkship self-assessment of students (RR 349/521) | Gain in knowledge and skills for 25/26 core medical conditions if FM clerkship before and 16/26 if after IM, ob-gyn and psychiatric clerkships | 4 |

| O’Hara et al (2000)74 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs with students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with 10 most frequent ENT diagnoses (RR 445/445?) | Higher than average levels of students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with the 10 most frequent ENT diagnoses (no numbers reported) | 3 |

| O’Hara et al (2001)75 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs with students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with 10 most frequent psychiatric diagnoses (RR 445/445?) | Higher than average levels of students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with the 10 most frequent psychiatric diagnosis (‘competent’: 52.1% vs 53.3% for total diagnoses encountered in clerkship; ‘confident/skilled’: 18.2% vs 19.1%; p<0.001) | 3 |

| O’Hara et al (2002)76 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs with students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with 10 most frequent ob-gyn diagnoses (RR 445/445?) | Lower than average levels of students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with 10 most frequent ob-gyn diagnoses (‘competent’: 49.6% vs 53.3% for total diagnoses encountered in clerkship; ‘confident/skilled’: 18.8% vs 19.2%; p<0.001) | 3 |

| Saywell et al (2002)77 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Patient encounter logs with students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with 10 most frequent muscular-skeletal diagnoses (RR 445/445?) | Lower than average levels of students’ perceived competence/confidence in dealing with 10 most frequent muscular-skeletal diagnoses (‘competent’: 49.5% vs 53.3% for total diagnoses encountered in clerkship; ‘confident/skilled’: 15.8% vs 19.1%; p<0.001) | 3 |

| Schwiebert and Davis (1995)78 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Pre–post clerkship self-assessment of students’ confidence for a list of skills; 4 cohorts (RR 358/358) | Mean change in students’ confidence significant (p<0.001); highest change for risk-oriented Hx taking (1.80); applying sensitivity/specificity (1.57); performing cerumen removal (1.44); geriatric evaluation and assessment (1.43); performing a focused Hx taking and PE (1.41); obtaining basic family information (1.40) | 4 |

| Sprenger et al (2008)54 | Austria | Y 6; 5 weeks; O | Post-clerkship self assessment of students (RR 30/30?) | Figure reporting level of competence of 30 students for a list of practical skills that they need to do themselves, but results not very clear | 2 |

| Svab (1998)57 | Slovenia | Y final; 7 weeks; O | Post-clerkship self assessment of students and tutors’ assessment; 2 cohorts (RR 135/175) | Students highest rate for knowledge on referral process (4.47/5), record keeping (4.47/5) and prescribing (4.45/5); tutors highest rate for students’ performance in communication (4.82/5) and cooperation with the team (4.84/5) | 3 |

| Townsend et al (2001)41 | UAE | Y 6; 10 weeks; O | Pre–post clerkship OSCE scores (RR 28/28?) | Improvement of scores: mean score 57.3/100 pre to 82.8/100 post-clerkship; consistent throughout the year and highest for stations on prescription writing, dealing with ethical problems and problem solving | 4 |

| Kirkpatrick level 3 | |||||

| Campos-Outcalt and Senf (1999)68 | USA | Y 3; varied duration; O; mixed setting | National data on FM specialty selection of graduates from schools with and without FM clerkship (RR 108/121 schools) | Mean change of % graduates entering FM specialty training in schools with FM clerkship (3 year pre and post start of clerkship) and schools without was 2.29, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.58, p=0.01 | 4 |

| Kassebaum and Haynes (1992)69 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | National data on graduation questionnaire and specialty selections and graduates entering FM specialty training for schools with and without FM clerkship (RR 57 with and 64 without/126) | % graduates planning FM specialty training (15.6) and certification (15.5) and starting FM specialty training (14.7%) for schools with required FM clerkship vs schools without (6.9%, 7.0%, 7.2% respectively) | 3 |

| Levy et al (2001)42 | USA | Y 3; 3 weeks; O | Data from matriculation and graduation questionnaire and final specialty selection for five cohorts of students (RR 913/969) | Rating the FM clerkship's value as ‘high’/‘very high’ increased odds to enter FM specialty training even after adjusting for socio-demographics and personal preferences (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.1 to 7.3, p=0.024) | 5 |

| Paulman and Davidson-Stroh (1993)32 | USA | Y 4; 8 weeks; O; rural | Pre–post clerkship questionnaires on specialty preferences and data on final specialty selection; 4 cohorts of students (RR 598/598) | Only 33 (5.5%) changed specialty preference post-clerkship: 23 (3.8%) positive change toward FM and 10 (1.7%) negative change (p<0.01); 15 (65%) of those with positive change entered FM specialty training | 4 |

| Senf and Campos-Outcalt (1995)47 | USA | Y 3; 6 weeks; O; mixed setting | Pre–post clerkship questionnaire on attitudes and specialty preferences and data on final specialty selection; 10 cohorts (RR 997/1095) | Only 1/4 of those who had a positive change toward FM specialty at end of clerkship entered FM specialty training | 4 |

| Stine et al (1992)70 | USA | Y 3/4; mixed setting; O/E; varied duration | Questionnaire for medical schools and national data on specialty selection on percentage of graduates entering FM specialty training in schools with and without FM clerkship (RR 104/126 schools) | 74% of schools in highest quartile of % graduates entering FM specialty training (≥17%) had a required FM clerkship vs 25% of schools in lowest quartile (≤7.7%) p=0.0013; association not stat. significant for elective clerkship | 3 |

?, No data available in the paper; Coeff, coefficient; DREEM, Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure; E, elective; ENT, ear-nose-throat; FM, family medicine/general practice; FP, family/general practitioner; Hx taking, history taking; IM, internal medicine; MCQ, multiple choice questions; O, obligatory; ob-gyn, obstetrics-gynaecology; OSCE, objective structured clinical examination; PE, physical examination; Ped, paediatrics; RR, response rate; Y, year.

Satisfaction with the teaching and learning experience

Twenty-six studies reported students’ evaluation of the quality of the FM clerkship in several countries such as the USA,28 38 43–47 the UK,39 48–51 Germany,52 53 Austria,30 54 Israel,55 56 Slovenia,40 57 Ireland,58 Pakistan,59 Sweden,34 Saudi Arabia,36 South Africa60 and Australia.61 Nineteen (73%) studies used evaluation questionnaires,30 34 36 38 39 40 46 47 49 50 52–57 59–61 two interviews39 51 and three focus groups,39 56 60 either alone or in combination with questionnaires, while six studies used students’ patient encounter or activity logs.28 43–45 48 58 The questionnaires used Likert or similar rating scales to assess satisfaction of students and most of them included open-ended questions. They were self-developed based on previous literature, local experience and clerkship’s learning objectives. Only two studies reported some reliability and validity measures for their questionnaires/patient encounter or activity logs,34 45 while one study used an internationally validated questionnaire for measuring the educational environment.53 Almost all questionnaires were handed out at the end of the clerkship, except for six studies that evaluated both at pre-clerkship and post-clerkship.36 40 49 50 52 59

Students rated their overall satisfaction with the FM clerkship as very high.30 34 36 38–40 47 49 52–56 59–61 In different countries with different levels of FM development, students repeatedly reported on the high quality of teaching and the variety of learning experiences during FM clerkships.28 36 39 43–45 48 50–52 56–59 61 62

Students were satisfied with the quality of the teaching setting and their relationship with FPs as they were enthusiastic, welcoming and friendly, willing to answer questions and set aside time to discuss with them.28 30 34 36 39 48 54 55 57 61

The most commonly cited satisfactory aspects of FM clerkships were exposure to a variety of health problems including acute and chronic problems, preventive and continuity visits,39 44 45 51 58 60 61 dealing with undifferentiated symptoms and managing common health problems,36 50 52 56 59–61 making holistic assessment of patients considering the psychosocial aspects of the disease,39 50 51 56 60 learning communication and physical examination skills,39 45 50–52 56 59 60 as well as about the organisation of primary care, its team and the role of FPs.36 39 56 57 60 Learning experiences in FM clerkships were reported as complementary and reinforcing to those in ambulatory care internal medicine and paediatrics.43 45

Change in attitudes to FM and career choices

Sixteen studies evaluated the impact of the clerkship on students’ attitudes towards FM as a specialty and their career choices.32 33 40 42 47 49 50 59 63–70 Attitudes were assessed either through attitudinal statements with Likert scales,40 47 63 64 focus groups33 65 and/or using interest/intention for a future career in FM as a proxy for attitudes toward FM.32 40 47 49 50 59 63–67 Nine studies evaluated both at pre-clerkship and post-clerkship32 40 47 49 50 59 63 64 66 with three of them at 1 year after graduation49 or at the time of specialty selection.32 47 Three studies looked only at post-clerkship attitudes,33 65 67 but one of them followed up students at 18–26 months after clerkship.67 One study also looked at the pre–post clerkship career intentions/preferences changes in internal medicine and surgery clerkships.64

Studies reported from countries with a well-established clinical and academic discipline of FM such as the Netherlands, UK, Ireland and the USA,32 47 49 50 58 64 65 as well as from countries with a mostly hospital-based/oriented healthcare system with no clearly defined complementary roles between specialists and generalists, such as Pakistan, Hong-Kong, Turkey and Germany.33 59 63 66 67 Although all quantitative studies except for one67 report inferential statistics, only two performed some multivariable analysis on career intentions/choices including gender and attitudes.63 64

Almost all studies report that the FM clerkship had a positive effect on improving students’ attitudes toward FM.33 40 47 50 63 65 The clerkship experience helped in counteracting the negative FM stereotypes as low-status and intellectually unchallenging.33 63 65 Yet, this attitude change does not necessarily translate into increase of interest in a future FM career,40 63 67 or increases interest only among those already interested in FM or not sure yet about their future career interests.50 59 The perceived likelihood of choosing the clerkship’s specialty increased in almost similar levels (around 30%) after FM, internal medicine and surgery clerkships, but the FM and surgery clerkships caused a shift of career preference motives from external (status, income and career prospects) to internal (variety of work and patients), suggesting a change of views regarding these specialties.64 In Turkey, even though there was no significant difference in attitudes towards FM after the clerkship, there was still a statistically significant increase in ranking of FM as a career choice.66

Increased interest in a FM career after the clerkship decreases over time49 and only a minority of those with an increased interest enter the FM specialty training.47 Only in one study of a rural US FM clerkship, did the majority of those who had a positive shift towards an interest in FM career enter FM specialty training.32

In the USA, medical schools with a required third year FM clerkship had higher numbers of graduates entering FM specialty training programmes compared to schools without a required FM clerkship.68–70 Even after adjusting for students’ sociodemographic background and specialty preferences, the educational value of the FM clerkship was an independent predictor of entering FM specialty training (OR 2.9 95% CI 1.1 to 7.3 p=0.024).42

Change in knowledge and/or skills

Thirteen studies report impact of the FM clerkship on students’ knowledge and/or skills. The majority are from the USA (10 studies),35 37 71–78 with only two studies from Europe (Slovenia and Austria)54 57 and one from United Arab Emirates.41 Two studies assessed with written examinations,71 73 one with objective structured clinical examination (OSCE),41 and one with tutor/preceptor evaluation forms.57 The rest of the studies used rating of students’ self-perceived competence/confidence.35 37 54 72 74–78 Only six studies used either a non-randomised controlled71 73 or the pre–post clerkship comparative35 37 41 78 design to adjust for academic performance and learning before the FM clerkship.

Areas with improved knowledge or skills attributed to the FM clerkship were preventive medicine for different age groups, clinical decision-making and problem solving, management of common health problems, focused patient evaluation, communication and cooperation with the practice team, record keeping, prescribing, referral systems, dealing with ethical problems, as well as a few practical procedures.35 41 57 71 78 In a US clerkship, students’ perceived competence/confidence was higher than average for dealing with the 10 most frequent ear-nose-throat and psychiatric diagnoses, but lower for obstetrics-gynaecology and muscular-skeletal diagnoses.74–77 The National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME II) scores of students who had taken the FM clerkship and those who had not (control group with similar scores in NBME I) had no statistically significant difference for the medicine and surgery parts of the examination. Students who had a FM clerkship scored significantly higher only in the public health items of NBME II.71

The increase in knowledge/skills due to the FM clerkship measured by improved multiple choice questions examination or OSCE scores remained even after prior experience in other specialties’ clerkships.41 73 Depending on the timing of the FM clerkship in the curriculum, there was self-reported gain in knowledge and skills between pre–post clerkship for 25/26 core medical conditions if the clerkship took place before and 16/26 if it took place after the internal medicine, obstetrics-gynaecology and psychiatrics clerkships.37 Yet, acquiring knowledge about undifferentiated and commonly seen problems, health promotion, disease prevention and patient education, importance of family dynamics in patient care and business aspects of medical practice, were reported as gains even when the FM clerkship was taken after all other clerkships.37

Impact on teaching FPs

The impact on teaching FPs was reported by 12 studies from the USA,28 46 62 79–83 Austria,29 30 the UK84 and Australia85 (table 6).

Table 6.

Studies reporting the impact of FM clerkships on teaching FPs and their patients

| TEACHING FPs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year) | Country | Clerkship features | Study methods | Key findings | Strength grade |

| Grant and Robling (2006)84 | UK | Y final; ? setting and duration; O | Action research; participation and interviews with all staff of a FP practice preparing to have final year students for FP clerkship (3 FPs); 5 months before and 1 year after having a student | All members of team enjoyed having students and experienced enhanced sense of professional identity and strengthened team ethics | 4 |

| Heath and Beatty (1998)79 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O | Coding and billing forms of 4 teaching FPs at 2 sites; 10 half day sessions during April and July (varied experience of student) (438 patients) matched with 10 half days same months (431 patients) without student | No significant differences in entering billing codes, performing office procedures or ordering diagnostic tests; mean nr patients 12.0 with/12.3 without student | 3 |

| Kearl and Mainous (1993)80 | USA | Y 3; ? weeks; O; urban | 4264 patient encounter forms (43% with a student) at clinic of FM department; 9 FPs and 3 FM residents (over 4 months: days with/without students); paired-sample design | No significant differences in mean number of patients/half day (productivity: 6.3 with and 6.1 without, p=0.7) and average billed charges (p=0.62) between days with/without student | 4 |

| Kollisch et al (1997)81 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Phone interviews with preceptors from 42 teaching practices (RR 35/38) | 55% commented on the time issue when student present (slowed down practice/had to stay longer); benefits and concerns reported | 4 |

| Levy et al (1997)82 | USA | Y 3; 2–3 weeks; O; urban | Postal questionnaire to all preceptors (RR 130/139) | Mean of 51±30 min/day increase in working time when student present; overall positive comments about teaching students; 87% had to stay longer; 31% saw less patients; 25% lost income; list of benefits and challenges provided; 58% complain of more time; positives: 40% positive interaction with student | 4 |

| Ricer et al (1997)83 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; mixed setting | Observations of 26 preceptor-student pairs; one research assistant timing teaching activities during visit and nr of patients of preceptor with (316)/without (131) student and comparing to non-teaching partner at same days; 19 full days and 7 half days July-August (first months of clerkship; little previous exposure of students so ‘max’ teaching time needed) | Estimate of 1.23 h in addition to usual day without students (teaching cost calculated at US$60); for 10 preceptors with partners no significant difference in number of patients (171 preceptor vs 164 non-preceptor partner) | 2 |

| Sturman et al (2011)85 | Australia | Y 3; 8 weeks; O; urban | Face-face interviews; quota sampling to represent diversity of teaching clinics/FPs (RR 28/29 teaching clinics; 60/61 FPs) | 83% comment on time issue (longer working day 30–60 min or >60 min); 52% quote ‘intellectual stimulation’ as benefit; rewards and challenges reported | 4 |

| Vinson and Paden (1994)46 | USA | Y 3/4; 3 weeks; O; mixed setting | Postal questionnaires to private preceptors who had taught during previous academic year (RR 46/56) | 40/46 reported increase of working time when with student (mean 46±32 min/day; median 45; range 30–120 min); 1% reported decrease in billing charges; 25/46 report ‘learning from students’ as a benefit; 17/46 report ‘time’ issue as a problem | 3 |

| Vinson et al (1996)62 | USA | Y 3; 4 weeks; O; urban | 10 328 observations: 55% from (RR 22/29) private teaching FPs; researcher directly observed 1 day with and without student; recording start and end of work and nr patient encounters; 12 academic FPs for two half-days with/without student; time and motion study; researcher observed and recorded activity (list of 35) in random selected times during the day/half-day; inter-rater reliability between observers >0.70 | Private FPs: mean increase of time when student present 52 min (95% CI 16 to 88) p.0.007; no significant change in nr patients/day, but significant change in productivity (nr patients/h): decrease of 0.6/h (95% CI −1.1 to −0.1) p=0.03; academic FPs spent 6 min less/day when student present (95% CI −67 to 55 min), but not stat significant; no change in nr pts/day and productivity; analysis of pt, admin or teaching activities: no major differences except academic FPs allow students to be semi-independent, while private FPs more passive/observing role | 4 |

| Sprenger et al (2010)30 | Austria | Y 6; 5 weeks; O | Self-administered questionnaires immediately after clerkship (RR 114/146); Likert scale to assess satisfaction with clerkship | 100% agreed teaching students was positive; 91% reported there was not enough time for tutorials | 4 |

| Pichlhofer et al (2013)29 | Austria | Y ?; ? weeks; O; urban | Online questionnaire survey (RR 59/74) | ∼92% feel always/frequently positively motivated by student’s presence; 51%: student’s presence caused need for more time always/frequently; ∼90%: teaching facilitates reflecting on daily work always/frequently | 4 |

| McKee et al (1998)28 | USA | Y 3; 6 weeks; O; urban | Daily activity logs and quality scores during the clerkship (RR 21/60; 105 sessions without and 98 with student) | No decrease in clinical productivity (number of patients/h: 2.74 vs 2.81 p=0.58) and overt-time hours (34 vs 41 min p=0.27); clinical productivity correlated to nr of patients seen independently by the student | 3 |

| Patients | |||||

| Bentham et al (1999)86 | UK | Y 6; 5 weeks; O; mixed setting | Questionnaires after consultations at 6 FP teaching practices (RR 130/148 patients) | 62%: no negative impact on the quality of consultation when student present; 98% would not refuse a student; 35% report advantages and 2% negative effect when student present; 2%: consultation longer when student present | 4 |

| Haffling and Hakansson (2008)91 | Sweden | Y final; 16 days; O; mixed setting | Questionnaires after consultation, handed out by 3 cohorts of students (RR 429 patients; 150/222 students reported) | 92%: no negative impact on quality of consultation when student present; 64% would not refuse a student; 1%: dissatisfied by student’s presence (longer consultation; difficult to talk about personal problems; other reasons); 22%: thought they could contribute to teaching students | 4 |

| Monnickendam et al (2001)90 | Israel | Y 6; 3 weeks; O | Questionnaire after consultation handed out by students at 46 teaching practice (RR 375/375? patients) | Majority: no negative impact on quality of consultation when student present; 77% would not refuse a student; 25% report advantages and 4% did not report a positive effect of student’s presence on the physical examination and medical interview | 4 |

| O’Flynn et al (1999)87 | UK | Y 4; unclear duration and setting | FP posted questionnaires to 25 patients the day after consultation with student present (RR 335/480) | 38.8%: learned more about their problem due to FP teaching the student; 33.3%: more time to talk when student present; 8.4%: left without saying what they wanted; 32%: less space to talk about personal problems; 34% would prefer to see physician alone | 3 |

| Price et al (2008)88 | UK | Y 5; 4 weeks; O | Questionnaire to consecutive patients after consultation with and without student; handed out by FP who also recorded length of consultation (RR 35/60 FPs; 1351 consultations with and 1119 without student) | Patients in consultations with vs without student present: validated scores for enablement 4.3 (3.9) vs 4.6 (3.9) p=0.06 and empathy 42.7 (8.0) vs 43.7 (7.2) p<0.01 (but no practical relevance); consultation length: 10.9±6 min with and 9.4±4.8 without student (p<0.01); 21% who had consented to a student present would have preferred to see physician alone; 72% learned more about their problem due to the FP teaching the student and 59% had more time to talk about their problem | 4 |

| Prislin et al (2001)31 | USA | Y 3; 1 day/week; O | Questionnaires after consultation handed out by FPs for 3 consecutive consultations with student (RR FP practices of 45/87 students; 121 patients) | 80%: no negative impact on the quality of consultation when student present; 76% report advantages and 6% negative effect of student’s presence; 10–12% consultation took longer when student present; 67% did not decrease time with doctor | 3 |

| Salisbury et al (2004)89 | Australia | Y 3; 2 weeks; O; urban | Questionnaires handed out by researcher before and after consultation with student. FP and student blinded (RR 8/30 FPs; 88/94 patients who consented/104 available) | 71% would not refuse a student; for any aspect (Hx taking, PE, procedure) student observing doctor: 93.2% expected, 88.6% occurring, 86.3% would accept in future; doctor observing student 77.2% expected, 69.55% occurring; 84% accepted; student alone for some part 42% expected, 20.4% occurring, 59% accepted | 3 |

| Pichlhofer et al (2013)29 | Austria | Y ?; ? weeks; O; urban | Questionnaires either pre or post consultation with student present (RR 28/74 FPs; 508 patients before and 346 after consultation questionnaires) | 95% (pre)−97% (post) report presence of student did not interfere with patient-doctor relationship; 75% did not report consultation took longer when student present; 5–13% who had consented to a student present would have preferred to see physician alone | 4 |

?, No data available in the paper; FM, family medicine/general practice; FP, family/general practitioner; Hx, history; nr, number; O, obligatory; Y, year.

Questionnaires, interviews and observations as well as coding/billing or patient encounter forms were used to collect data. Only three studies used a comparative non-randomised approach where clinical sessions with students were compared to those without students,79 80 or teaching FPs were compared to non-teaching colleagues.83

Teaching FPs are overall satisfied with their role as they report excitement from teaching and enthusiasm from interacting with students and investing in their development.30 62 81 82 85 They also report learning while teaching as interaction with students and their questions provide stimulation to keep up to date with developments of medical knowledge, as well as encourage reflective practice and have a positive effect on their professional development.29 62 81 84 85 Involvement in teaching students also provided an opportunity to upgrade clinical skills and develop teaching skills and improved relationship with other staff and team development, as well as their professional status and relationship with patients.29 81 84

The main disadvantages reported by teaching FPs were slowed down patient flow and increased working hours.29 46 62 81 82 85 Data on length of workday and productivity (number of patients seen) when a student is present are based mainly on self-report, although two studies observed and timed consultations of FPs with students,62 83 and two studies analysed patient encounter or billing/coding forms.79 80 The increase in working time when a student was present, as reported by FPs, ranged from 30 to 120 min.62 82 85 The observed and timed difference in consultation activities of teaching FPs with their non-teaching colleagues was 1.23 h.83 No differences were reported regarding number of patients, charging/billing of patients, performing of practical procedures and ordering of diagnostic tests between FPs’ visits with and without a student.79 80 One study that had a low response rate, reported no decrease in clinical productivity (number of patients/hour) or overtime hours, while clinical productivity correlated to the number of patients seen independently by the student.28

Impact on patients in the teaching practice

The impact on patients was reported by eight papers from the UK,86–88 the USA,31 Australia,89 Israel,90 Sweden91 and Austria29 (table 6). All of them used questionnaire surveys with attitudinal statements and Likert scales and are non-comparative, except for two studies where patients seen with students were compared to those seen without students or before and after the consultation with a student.88 89 Questionnaires were locally developed and piloted, but no validation was reported. Only one study adapted an already validated questionnaire.88

The majority of patients do not report a negative impact on the quality of their FM consultation when a student is involved29 31 86 90 91 and would not refuse a student.86 89 90 91 Validated scores for enablement and empathy were not significantly different between patients who had a consultation with a student present and those without.88 Patients in some studies even reported some advantages when a student was present such as getting a second opinion, better explanations, more time to talk about the problem and a more thorough history taking and examination, as well as personal satisfaction and self-esteem due to contributing to education of future physicians.31 86 88 90 91 In an Australian study, patients would accept more involvement of the student in history-taking, physical examination or procedures than expected by them before or occurring during the consultation.89 In Sweden, some of them felt they could contribute to teaching through being facilitators of the development of students’ skills and attitudes, exemplars and experts of the medical condition, as well as providing a real context for learning.91

In some studies, a small number of patients (1–6%) reported a negative effect of the student’s presence during the consultation, such as longer consultations31 86 91 or more difficulty/less space to talk about personal problems.87 91 Although one study reported a significant difference in length of consultations with and without students present as recorded by the FPs,88 in other studies, the majority of patients did not think that either their consultation took longer when a student was present29 or that time with their FP or the FP’s attention was reduced due to the presence of a student.31 87

Discussion

Summary of main findings and comparison with previous reviews

This systematic review on the impact of FM clerkships in undergraduate medical education found that they are highly valued by students and overall well-accepted and even beneficial to the teaching FPs and their patients. The 64 reviewed studies reported from a wide range of countries with both well and less-developed academic and clinical FM. None of the reviewed studies evaluated an impact beyond the Kirkpatrick outcome level 3 and only one study achieved grade 5 of the BEME’s strength of findings.

The reviewed studies reported students’ satisfaction with both the content and process of teaching and learning in FM clerkships. The main contributions are the variety of common clinical experiences encountered including chronic, continuity and preventive visits; integration of previous learning and further development of communication and focused physical examination skills; becoming familiar with the organisational and business aspects of the medical practice as well as developing a biopsychosocial approach to patient care, looking at the patient not as a disease but as a whole person in the context of the family and community. Students value the enthusiasm and positive attitude of teaching FPs and their staff that leads to quality teaching. Based on the few studies that assessed knowledge and skills, the FM clerkship enhanced previous learning in other specialty clerkships and provided unique learning, especially on dealing with common acute and chronic conditions, health maintenance and disease prevention, communication and problem-solving skills.

The teaching and learning experiences in FM clerkships seem to improve students’ attitudes towards this specialty, and influence their career intentions and decisions. Yet this new or enhanced interest in a FM career due to the clerkship does not persist without change. While the FM clerkship experience is important to counteract students’ negative stereotypes about FPs and their work, and inform career choice, a definitive career shift to FM requires a comprehensive and complex intervention package due to the broad scope of factors that influence the specialty choice process from premedical school into practice life.40 92 93

Although there is variability in clerkship settings and countries, the overall message is that FM clerkships provide a valuable and satisfactory educational experience for medical students with the main contribution not in a unique list of diagnoses or procedures, but in a different approach to practicing, teaching and learning medicine derived from the person-centred system-based worldview of FM.60

Teaching FPs report increased job satisfaction and stimulation for professional development due to involvement with students. They also recognise some negative impact in their work as a result of teaching such as increased workload and less productivity, although findings are not consistent. Patients in FM practices involved in FM clerkships are open and willing for students to observe and participate in their consultations. Overall, student’s presence and participation has a positive impact and increases patients’ satisfaction with their consultations, and there is room for even more active involvement of both patients and students.

Previous reviews on teaching and learning in ambulatory care in North America have reported its positive contribution in the education of medical students, while emphasising the variety of settings, measurements and outcomes used by different studies, and the low number of studies applying rigorous methods to evaluate educational outcomes.16–18 Our systematic review was the first, to our knowledge, focusing specifically on the impact of FM clerkships, and it covered a longer timeline (1990–2013) and included a wider spread of countries. We noticed an increase in studies on the impact of the FM clerkships in countries where this discipline does not yet have a clearly defined status in the healthcare system or is under development. This reflects the pursuits to strengthen FM and primary care in these countries and the need for further data to support its integration in the basic education of future physicians.

The rigour of research on the evaluation of ambulatory care educational outcomes has been previously reported as weak, especially in regard to limited tools used to measure learning outcomes and the lack of generalisability.17 18 Our review assessed the quality of studies’ findings with the BEME grades of strength and the Kirkpatrick outcome evaluation levels that were not used in previous reviews of ambulatory care teaching and learning. Our findings show that quality of research on evaluation of FM clerkships is still weak, even though medical education research and practice on assessment and evaluation tools has been growing rapidly in the past decade.94

Most of the studies that evaluated the impact on students used self-assessment through locally developed instruments (patient encounter logs, evaluation or attitudinal questionnaires), without reports of validity and reliability. Very limited adjustments were made for the patient mix of different FM practices, locations and seasons, as well as the timing of the clerkship on the academic year and prior learning in other clerkships. This limits the generalisability of findings to other institutional, educational and patient care settings. Studies that evaluated the impact on teaching FPs and/or their patients used mainly self-designed instruments without a thorough validation and with limited adjustment for physician-to-physician variability in clinical and teaching experiences and patients’ mix. Most of the studies relied on self-reporting by FPs and patients, and only a few attempted direct observation or validation from other sources.

None of the reviewed studies reported changes in organisational practice or improvement in patients’ health outcomes as a direct impact of learning in FM clerkships, yet this is common in medical education reviews.24 This is to be expected, as such a level of evaluation requires a long follow-up and it is impossible to adjust for the complexity of factors that influence the practice of patient care besides the basic education of the practicing FPs.95

Even in the light of these methodological problems and differences in organisation and evaluation of FM clerkships in the reviewed studies, the overall consistency of results across different studies and countries supports the generalisability of findings about the positive educational impact of FM clerkships.

Strength and limitations

This systematic review was based on a comprehensive search strategy using the PRISMA guidelines and included the major databases for medical and educational research. The reviewers had previous experience with medical education research and come from well and also from less-developed settings of clinical and academic FM. The lack of meta-analysis is a limitation of this systematic review, but this was not possible due to the variety of study designs, tools and outcomes used, and the nature of reported results. As all reviewers are FPs, passionate for clinical and academic FM, this may have introduced bias in the analysis and synthesis of results. Owing to language and accessibility limitations, the review may have missed other studies published in this research area.

Implications for future practice and research

Research on the impact of FM clerkships in countries with a less-developed status of this discipline has been gradually growing in the past decade. Yet, it should not just repeat, but rather build on the lessons learned by research in countries with a developed status of FM, the best current recommendations on assessment and programme evaluation, as well as the local context and culture. Future studies that include different medical schools and countries, and use standardised and validated evaluation tools would increase the generalisability of the current findings and determine best interventions and practices in FM clerkships.

Triangulation and comprehensive evaluation involving the different stakeholders of FM clerkships such as students, teaching FPs and patients, medical school and healthcare institutional leadership, other primary care or hospital-based specialists, other staff in teaching FM practices, etc, need to be the focus of future studies. This becomes very important in light of the ‘chilly academic climate for primary care’ and the ‘cultural bias against primary care’ in some medical schools and regions.96–98 The negative attitudes of hospital specialists toward the involvement of FPs in undergraduate medical education may not only be due to ‘specialty rivalry’ for curricular time, teaching resources and academic prominence, but also due to the differences between the ‘health and care’ approach of primary care and the ‘disease and cure’ approach of secondary/hospital care.60 96 99 The resistance towards FM and its development with the increasing involvement and contribution of FM in undergraduate education needs to be further explored in future studies. This would provide a more comprehensive view of the impact of FM clerkships and further insight for countries where FM is still in the early stages of pursuing entrance and acceptance into the medical academia.

In light of previous reviews suggesting longitudinal versus block ambulatory clerkships to ensure more continuity of patient care and student-teacher relationship,17 and recent reports on the value of longitudinal integrated clerkships,19 100 future research should also focus on longitudinal FM clerkships and their contribution in the education of future physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs Cil Leytens at the Department of General Practice, University of Antwerp, for her valuable help in retrieving some of the full-text papers and Dr Elizabeth Swain in Scotland, UK, for the English language editing. The authors would also like to acknowledge the JOIN-EU-SEE Erasmus project of the European Union as the idea and the work for this paper developed during a visit of ET at Department of General Practice, University of Antwerp, in November 2013, which was funded by a JOIN-EU-SEE staff exchange scholarship.

Footnotes

Contributors: ET and RR developed the idea for the study. ET, RR and NRM developed the search strategy and ET performed it. ET, RR, NRM and KH were all involved in the review of the papers. ET drafted the manuscript. RR, NRM and KH commented on the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Organization of Family Doctors. The contribution of family medicine to improving health systems: a guidebook from the world organization of family doctors. 2nd edn, Radcliffe Publishing Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor RB. Family practice and the advancement of medical understanding. The first 50 years. J Fam Pract 1999;48:53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krztoń-Królewiecka A, Švab I, Oleszczyk M et al. . The development of academic family medicine in central and eastern Europe since 1990. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2296-14-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haq C, Ventres W, Hunt V et al. . Where there is no family doctor: the development of family practice around the world. Acad Med 1995;70:370–80. 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler JK, Carelli F, Lionis C et al. . The wind of change: after the European definition—orienting undergraduate medical education towards general practice/family medicine. Eur J Gen Pract 2007;13:248–51. 10.1080/13814780701814986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thistlethwaite JE, Kidd MR, Hudson JN. General practice: a leading provider of medical student education in the 21st century? Med J Aust 2007;187:124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinowitz HK. Family medicine predoctoral education: 30-something. Fam Med 2007;39:57–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. . Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training: world health organization guidelines. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA et al. . Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHITCOMB ME. Ambulatory care education: what we know and what we don't. Acad Med 2002;77:591–2. 10.1097/00001888-200207000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worley P, Prideaux D, Strasser R et al. . What do medical students actually do on clinical rotations? Med Teach 2004;26:594–8. 10.1080/01421590412331285397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray E, Modell M. Community-based teaching: the challenges. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:395–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oswald N, Alderson T, Jones S. Evaluating primary care as a base for medical education: the report of the Cambridge community-based clinical course. Med Educ 2001;35:782–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00981.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brekke M, Carelli F, Zarbailov N et al. . Undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine throughout Europe—a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:157 10.1186/1472-6920-13-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yonke AM, Foley RP. Overview of recent literature on undergraduate ambulatory care education and a framework for future planning. Acad Med 1991;66:750–5. 10.1097/00001888-199112000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]